NELSON,

HOWARD,

AND

“THE LOVE

SHACK”

After years of gazing out over a lunar-like no-man’s-land walled by concrete and barbed wire, the East Berliners who crowded against the barrier erected by the Soviets in 1961 could never have imagined the magnitude of lights, sound, production, or the simple freedom that Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters enjoyed, to stage his band’s grand 1979 work, The Wall, in Potzdamer Platz on 21 July 1990. Only the previous week, West German troops had finished sweeping the area where two hundred thousand fans now stood for unexploded bombs and mines. Their Eastern counterparts danced atop a long line of armored personnel carriers, hooting and hollering in their fatigues as Waters unwrapped the iconic double album onstage, and East hugged West in a new summer of love. I journeyed to this massive European party as a WBCN correspondent, phoning reports back to America from a bank of phones set up in a trailer jammed against the Berlin Wall. After nearly forty years of Soviet injustice and Hitler’s nightmarish reign before that, this whole area reeked tragically of history, like some decaying roadkill left by a continent-wide collision. But the immense sound of nearly a quarter-million voices booming into the Berlin night: “Tear down the wall! Tear down the wall!” shouted down the past. Could it be? Could a glimmer of hope be shed for these Berliners, that the end of their long nightmare was truly at hand?

Afterward, a few of us roamed about in a mostly deserted backstage area. Dave Loncao, a high-level Mercury Records rep, flashed a laminated pass and performed his Big Apple razzle-dazzle to secure a few bottles of red wine, all that was left from the considerable bar that had catered earlier to hundreds of VIPS. We drank enthusiastically, talking about the concert and the politics of a new Europe until the last bottle had been drained. Loncao grumbled, “What do you want to do now? We’ll never get out of here with all the traffic!”

“I guess we just have to hang out or start walking back to the hotel,” someone offered, not a happy prospect since the place was several miles away.

“Maybe we should just walk over and take a piss on the Berlin Wall!” someone else piped in. I’d like to say it was my idea, but the wine had begun interfering with any accurate record keeping by that point. Let it stand that “someone” in our group had the brilliant thought.

“Like the cover of Who’s Next?” Loncao observed, chuckling with a hand already on his fly.

“Exactly!” And with that, our little band of American broadcasters lurched over, offering up our own special tribute to the absurdity of building that ugly ribbon of concrete and metal in the first place.

Carter alan

A new decade had arrived, a noisy and kicking brat named 1990. Loud and brash, the imp quickly drowned out its older, more reserved, brothers and sisters born during the eighties. Just the end of the Cold War, the breakup of the Soviet Union, and the reuniting of East and West Germany was astounding enough to warrant special attention. But to that remarkable turn of events, add Lech Welesa’s presidential victory to break the back of Poland’s communist government and Margaret Thatcher’s resignation. Twenty-five cents bought a first-class stamp and a gallon of regular gas averaged around $1.15. Sporting fans watched Edmonton deny Boston the Stanley Cup (again); the Reds swept Oakland in the World Series; and Joe Montana led the 49ers in a rout of Denver at Super Bowl XXIV. The Simpsons debuted on Fox-TV, Seinfeld on NBC, while Home Alone, Dances with Wolves, and Ghost became box office monsters. As M. C. Hammer’s Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ’Em sat at number 1 for twenty-one weeks and sold ten million copies, an unknown band in Seattle named Pearl Jam played its first gig and Nirvana visited Boston for the second time.

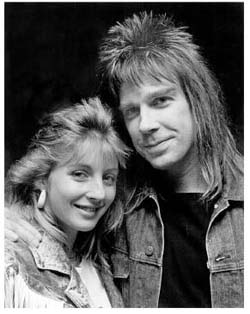

Big hair’s last stand: the eighties give way to the nineties. Carter Alan and (future) wife Carrie Christodal. Photo by Roger Gordy.

The eighties had been very good to WBCN, the station arriving at 1990 on the crest of local popularity, as well as national respectability. Friday Morning Quarterback looked back on the previous years by polling the professional communities of both broadcasting and the record business nationwide, naming ’BCN as “Best Station of the Decade.” In the 1990 Rolling Stone Reader’s Poll, and for the ninth time in ten years, the station was voted one of America’s best large-market radio stations. But just as the fresh year had brought sweeping changes to world affairs, politics, and culture, 1990 also perched ’BCN on the edge of a worrisome and uncertain future after a decade of consistency and mastery of its domain. Several personalities departed from the air staff, including Tami Heide, who transferred to KROQ for a long and acclaimed career, and Lisa Traxler, who ended up on rival WZLX in 1992. Billy West and Tom Sandman both exited the production department, the latter stepping up to a program directorship at crosstown WBOS-FM: “I didn’t see any future in me getting into programming at WBCN; I didn’t think Oedipus was going to go anywhere soon.” Sandman was correct; ’BCN’S now-veteran program director remained secure in his position, presiding over the latest changes in his staff, which would prove to be minor compared to the seismic ones arriving in just a few years. Tony Berardini endured as station general manager and Infinity vice president but, by the end of 1989, had hired a general manager for KROQ and given up the arduous schedule of flying back and forth to LA every two weeks. “The real issue became that ’BCN started getting more competition from ’ZLX,” Berardini explained. “That station was chipping of enough of our ratings that it made it difficult to reach the budgets. Now I could sit down and focus on ’BCN.”

In the news and public affairs departments, the twin defections of Katy Abel and Matt Schaffer left a gaping hole. Oedipus prevailed upon Sherman Whitman, who had been part of the WBCN news team for three years until October 1987 when he left to work at WXRK in New York City, to return as news director. Whitman found the new appointment satisfying: “There was still a commitment to the news and public affairs at ’BCN; people felt they got information there that they couldn’t get anywhere else.” Then, Oedipus tapped Maurice Lewis, who sported an extensive list of credentials in local radio and television journalism, to take over for Schaffer on the “Boston Sunday Review” (BSR). Lewis said, “I had total and free reign without any interference from management; that was the beauty of the show. You couldn’t have asked for a more supportive environment.” The two new arrivals, along with Charles Laquidara, soon brought great honor to WBCN in June 1990, on the occasion of black political activist Nelson Mandela’s historic visit to Boston. Sadly, as triumphant as that moment would be, it would also represent the final hurrah for an acclaimed (and some would say, essential) part of WBCN’S original manifesto in 1968.

After twenty-seven years of harsh imprisonment at the hands of the pro-apartheid South African government, Mandela had been released from prison as internal hostilities and international pressure mounted on the white ruling party to hand over power. Eventually, a multiracial government would be installed with Mandela as its head, but in the immediate afterglow of his newfound freedom, the most famous and revered symbol of racial equality since Martin Luther King Jr. decided to embark on a goodwill tour of America. The important and historic meetings with national leaders and fellow activists would mostly occur in New York City and Washington, D.C., but Mandela planned a one-day, whirlwind visit to Boston, which generated extraordinary excitement from ordinary citizens and local politicians alike. Whitman enthused, “Katy [Abel] was gone by then, but she had done “Commercial Free for a Free South Africa” in 1985, and to think that Mandela himself would come to Boston five years later!”

As the time wound down swiftly to the historic visit, and on the day before the African leader’s 23 June arrival, WBCN was recognized for its role in popularizing the anti-apartheid movement. The Boston City Council surprised Charles Laquidara with an award for “his Commitment to Ending the Apartheid Regime in South Africa,” as a result of the on-air campaign to boycott Shell Oil. This was followed by a second citation from the Massachusetts House of Representatives in acknowledgment of his “Continuous Public Education and Support for a Free South Africa.” A similar award went to Maurice Lewis, as representative of the public affairs department, in recognition of WBCN’S efforts toward these initiatives. While the accolades were being handed out and photos snapped, Sherman Whitman worked feverishly down the hall, making final preparations with the station engineers for WBCN’S in-depth coverage of Mandela and his wife Winnie’s visit.

Maurice Lewis had helped to coordinate a simultaneous playing of the South African national anthem on various Boston radio and television stations at 12:01 on the day Mandela arrived. “It was the first time we got competing stations to go along with each other to do anything!” Lewis laughed. “Also, working with [Urban radio station] WILD, we were involved in organizing a parade launched from Roxbury, which wound its way through Back Bay and over to the Hatch Shell.” After participating in the motorcade, Lewis arrived at the massive tribute concert on the Esplanade where over three hundred thousand adoring citizens waited, part of a visit described by Ebony magazine as “Mandelamania.” “It was a Saturday afternoon when Nelson Mandela came and spoke at the Hatch Shell,” Whitman recalled. “We were there from the start of the day to the finish. We carried it all live: Mandela’s entire speech, the music the artists were playing, and the words of Governor Michael Dukakis and Senator Ted Kennedy. There was a sea of Mandela T-shirts out there . . . like seeing a rock star.” Meanwhile, Lewis, astonished at the size of the crowd that lined both sides of the Charles down to Massachusetts Avenue, appeared several times on the big stage. “I was called back multiple times because the Mandela entourage was late. I received those dreaded instructions: ‘Fill! Fill!’” he laughed. “But because of that I got the chance to ‘fll’ onstage with Danny Glover and Harry Belafonte; those [moments] were great.”

This day, auspicious as it was, would end up being the last big hurrah for WBCN news, signaling the twilight years for the department as 1991 arrived. First, Lewis decided to move on, with no regrets: “It felt great to work on a show that brought opinions, cultures, theater, drama, politics, and diverse people from Boston together; that’s what the ‘Boston Sunday Review’ had always been designed to do.” During the same period, as Whitman described, his role at the station changed: “[Oedipus and Tony] said, ‘We’re going to have you stop doing the news and let Patrick Murray handle things.” Murray, who had started off two years earlier as a news department trainee and Whitman’s intern, was surprised by the move. He mentioned, “I didn’t know about it beforehand; Oedi just called me into his office and told me, ‘You’re the news director.’” Murray had worked his way up to be a well-known morning sidekick on Laquidara’s show, due to his offbeat and free-spirited delivery of news, traffic, ski, and surf reports. “It was a time when you could get your news in other places, so on the Mattress we did it differently. I’d make sure the report was on the pulse of what was going on and then have some fun with it, like a Saturday Night Live sketch.” Though the official title of news director had been conferred upon him, Murray didn’t necessarily see much increase in the scope of his responsibilities, nor a directive from Oedipus to change his style. He continued to gather information for Laquidara and deliver it with his wise-cracking, sardonic slant. “Once, as I was getting ready, I noticed they had the agricultural report up on the AP newswire. So, I did hog slaughters, sheep slaughters, the rye crop, and the wheat crop numbers instead of a business report. We played a little Raising Arizona bit behind it with some sound effects. No biz report, just the cattle kill for the week!”

As Murray churned out his comedic, and more digestible, version of “the news,” Oedipus unveiled his plans for the displaced Whitman, who explained, “With Maurice gone, they needed someone to do the BSR, so I handled that for the rest of my tenure there [till June ’93].” Whitman did not turn bitter over these changes; he realized that the times were changing and that he personally couldn’t stem the tide: “Every music station had begun cutting back on its news commitment, especially on the FM dial. There was specialization: music stations would now be doing music, and news stations would now do just news; ’BCN was no exception to that.” In an ongoing series of deregulation moves in Washington, the FCC granted radio station owners far more latitude to run their businesses as they saw fit. The relaxed state of ownership rules and public affairs requirements set off a wave of layoffs as companies raced to reduce their bottom lines by slashing staffs, consolidating stations, and standardizing formats. By having Murray handle “Big Mattress” duties and also the news, WBCN management eliminated a full-time job and maintained spending on its Sunday newsmagazine show at a part-time level. “I turned out the light in the WBCN news department,” Whitman acknowledged. “And that was one of the saddest things to do, simply because, for me, ’BCN was home [and] all the people there . . . that was my family. All the things we did there together, at 1265 Boylston Street, we did to make radio great. Somewhere down the road, someone made the decision that we don’t want to be great anymore; all they cared about was making fabulous profits. I left because I felt my time had come to an end.” Not to take anything away from Murray, who was given the football, ran with it, and scored points, but from this point on, news “dissecting” on WBCN was a thing of the past.

On 28 February 1993, WBCN’S staff gathered at the Hard Rock Café in Back Bay to celebrate the station’s twenty-fifth birthday. Invitations had gone out to current workers as well as all the former employees who could be found. “It began with Carla Wallace, an original ’BCN person at Stuart Street,” David Bieber explained. “She called me in December ’92 and said that we should do a twenty-ffth-anniversary party.” It seemed like an obvious idea, but Wallace had the additional vision that the party should be open to anyone who had ever worked for ’BCN. The happy result was that four hundred employees jammed into the Hard Rock, their buzzing conversations easily drowning out the blaring music, that is, until the members of the J. Geils Band found their way to the stage and serenaded the crowd with an a cappella version of “Looking for a Love.” It was the band’s first public performance since it had broken up a decade earlier and a symbol of respect, not only for singer Peter Wolf’s former radio home, but also for the long lineage of legendary characters that had inhabited 104.1 FM. Stars from former times arrived in force: J.J. Jackson, Tommy Hadges (now president of Pollack Media Group), Billy West (the voice of the Ren and Stimpy show), WBCN’S founder and original owner Mitch Hastings, Danny Schechter, John Brodey (a general manager at Giant Records in LA), Norm Winer (a program director in Chicago), Maxanne Sartori, Ron Della Chiesa, and Eric Jackson. Aimee Mann, James Montgomery, and Barry Goudreau of Boston mingled about. Susan Bickelhaupt queried in her Boston Globe article about the anniversary, “25 years later, what has replaced rock station WBCN-FM? Nothing. It’s still ’BCN, 104.1. Sure the jocks are older and drive nicer cars, and you can even buy stock in parent company Infinity Broadcasting, which is traded on the NASDAQ market. But the station that signed on as album rock still plays album rock, and is perennially one of the top-ranking stations and a top biller.”

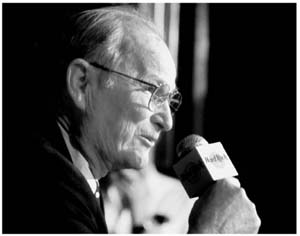

T. Mitchell Hastings addresses the crowd at the Hard Rock Café in 1993 for WBCN’S twenty-fifth anniversary. Photo by Dan Beach.

A rumor passed about the room that night, given weight since it allegedly came from a WBCN manager: something major was going to happen with one of the station’s primary weekday air shifts. Since lineup changes at the station occurred with the frequency of Halley’s Comet appearances, this warranted front-page news (or, at least, endless speculation). Was a member of the famed daily triumvirate of Laquidara, Shelton, and Parenteau finally bowing out? Oedipus and Tony Berardini weren’t talking, but their conspicuous silence seemed to support that something big was about to happen. Industry analysts caught a whiff of the rumor as well, but it came from a different source: New York, on the nationally syndicated Howard Stern show. In the years since the former Boston University student had attempted to find work at ’BCN, the announcer had made his mark outside of Boston, rapidly rising to become a hurricane force in radio with his undeniable wit, lapses of taste, and incessant sparring with the FCC over established indecency boundaries. The shock-jock had always desired to return to Boston, hinting that this might be a possibility in the near future, but the official confirmation of that did not arrive until 8 March 1993. That night, WBCN began airing Stern’s nationally syndicated morning show, on tape delay, following Mark Parenteau’s afternoon shift.

Tony Berardini told Virtually Alternative in 1998, “Howard Stern was doing extremely well at Infinity’s WXRK, and then at ’YSP, Philly. Oedipus and I kept looking at it, thinking, ‘Wow, the company is going to want to syndicate him in Boston, too, why wouldn’t they?’ It was one of those things we knew we were going to have to deal with, yet Charles Laquidara still had good numbers in the morning. Even Howard used to listen to him when he went to Boston University. With this in mind, we went to Mel with the idea of running his show by tape delay at night. We had an immediate opportunity there, and we decided to take advantage of it.”

“Howard wanted to be on the radio in Boston, and I was able to make that happen because I could put him on at night,” mentioned Oedipus. “Everywhere else [with the exception of KOME in San Jose], he did the mornings, but Mel allowed me to make the decision to tape the show and play it later.” Oedipus did not regret his decision: “Howard is a monumental talent; it just can’t be denied. I remember many a time driving home from work and then just sitting in my garage, not getting out of my car, because I didn’t want to miss a moment.” Listeners tended to react to Stern’s show simply and starkly: they either loved the DJ or hated him. Those who disliked his presence on WBCN found other nighttime options, but those attracted to his brand of radio comedy became riveted . . . for long periods of time. “Nighttime listening to rock stations was really falling off at that time, and we had nothing to lose,” Tony Berardini told Virtually Alternative. Very quickly, as nighttime ratings at WBCN increased dramatically, the gambit, it seemed, had played out to be a shrewd and successful decision.

“Metal Mike” Colucci was one of the part-time employees now called upon to man the studio each weeknight, acting as a board operator during the taped Howard Stern program. Although just a lowly, anonymous worker bee to the mighty Stern, Colucci would be elevated by that jock’s rabid following to the status of infamy. This was one of the secrets of that show’s success: the shock-jock’s ability to whip up drama, creating form and substance out of something that, when examined more closely, really warranted no such time or attention. Who cared? In Stern’s hands, though, it seemed that a lot of people actually did (at least for four or so hours a day). On the evening of 27 July 1993, Reggie Lewis, a twenty-seven-year Boston Celtics rising star, collapsed on the court and died from a heart defect while Howard Stern’s taped program ran on WBCN. Shocked, Mike Colucci phoned Oedipus to ask what to do. “He told me, ‘Fade out Howard, play “Funeral for a Friend” [by Elton John] and announce that Reggie Lewis is dead.’” However, as an inexperienced DJ, Colucci couldn’t handle the wave of emotion that swept over him as he spoke on the air: “I got all choked up; I went into this terrible tailspin before I got back into Stern’s show as fast as I could.” Unbeknownst to the young board op, one or more of Howard Stern’s ardent Boston fans taped the show and overnighted a recording to the shock-jock for his live broadcast the following morning. Stern played the tape on the air relentlessly, downplaying the drama of Lewis’s death to focus on Colucci’s painful on-air gaffe. “It turned out that he did forty-five minutes on me, saying things like, ‘If this guy is acting, he’s a genius.’ Red faced, he endured the episode over and over again, taking a lot of good-natured ribbing from a host of people who never even heard the original episode. “At the time, Howard had the biggest radio antennae going; nobody was going to break in on his broadcast. He could stick it wherever he wanted.”

Many employees and fans of the station disagreed with the strategy of adding Stern to the WBCN lineup, finding the move troubling, at the very least. Bob Mendelsohn, as general sales manager, would work intimately with the new syndicated show, selling airtime to local and national clients: “The first time I heard Howard Stern, I hated it. It just embarrassed me. It wasn’t his sense of humor; it was his complete elimination of standards. These were the boom years; everything was about stock price and profits now.”

“When Howard Stern got [to ’BCN], it was all about how much money he was making [for the company],” Danny Schechter observed. “These were the values of Mel Karmazin. They didn’t really care about Boston, [and] they didn’t really care about the audience; it was the market and getting market share. That’s what mattered to them: it was about the shareholders.”

“I know a lot of people mark Howard Stern as the beginning of the end, and maybe it was,” Tim Montgomery said. “Because, in a way, Ken Shelton and his Lunchtime Salutes [and] the crossovers between Charles, Ken, and Parenteau: that represented the old ’BCN. God, there was some brilliant radio! Then, with Howard Stern and the whole coarsening of the culture, the station took on that mean, macho, sexist [attitude] with eighteen-year-old-boy fart humor and vagina jokes. That’s not what ’BCN was! It was smart; then it became stupid. The dumbing down of the ’BCN audience became the whole new thing.”

“That Mel had this amazing asset in New York and then was able to multiply that asset by putting it on all these stations, as a corporate move, bordered on brilliant,” Bob Mendelsohn admitted. “But it was everything that ’BCN had never been before. WBCN had always been credible and sincere; this was smart-ass radio. As an employee of the station, that’s when my affection and my pride in working there started to go in a different direction.”

A second seismic event that shook WBCN in 1993 had been simmering since the year before, when Infinity Broadcasting, which owned and operated eighteen radio stations at this point, had entered into an agreement to purchase WZLX-FM in Boston. The $100 million deal with Cook Inlet Radio included the acquisition of two other radio properties in Chicago and Atlanta, and was made possible by another relaxed ownership edict from the FCC that increased the number of radio stations a company was permitted to own. Previously, a single operator could only possess a total of twelve AM stations and twelve FMS, but those limits were increased to a total of eighteen AMS and eighteen FMS. Additionally, the previous rule that a single operator could own a maximum of one AM station and one FM in a single market was increased to two each, as long as there were fifteen or more radio properties in the area and that listener share did not exceed 25 percent of the market’s total. Infinity chomped at the bit to take advantage of these revised, business-friendly rules: although the FCC edict did not go into effect until 16 September 1992, the company proudly trumpeted its pending purchase in an 17 August press release. Obtaining final FCC approval would push Infinity’s official takeover of WZLX into ’93, but when all was said and done, WBCN’S biggest rival had suddenly been made a member of the same family. The two stations had been kicking each other under the table since the mideighties, but Mel Karmazin now demanded that the horseplay stop immediately. “The day that [Infinity] closed on buying WZLX, [Karmazin] got the sales managers from both stations together for a meeting,” Mendelsohn recalled. “His message was, ‘You guys have been out on the street trashing each other for years. As of today, that stops; you’re working together.’”

Not only did the new association with WZLX mean that the sales strategies at both stations could be allied and results maximized, but Oedipus now had the opportunity to collaborate with his former adversary, program director Buzz Knight, in working out a two-station approach that minimized the considerable musical overlap of their respective formats. This appeared to be the answer to WBCN’S programming dilemma of addressing the tastes of two steadily diverging radio audiences. “This is what happens when you have a radio station whose life is so prolonged; you outgrow your audience,” Oedipus pointed out. WBCN could either grow old with those longtime (twenty-five- to fifty-four-year-old] fans, becoming essentially a classic rock radio station, or embrace the younger listeners who were moving into the station’s demographic target. With WZLX in the mix, the decision essentially became moot. “We elected to stay younger; WBCN had to. We focused on the eighteen- to thirty-four-year-olds.” Making that transition would occupy a year or so, but the first adjustment, proposed almost immediately, became the station’s third seismic shakeup in 1993.

Along with conducting the necessary music and image modifications to focus on the younger eighteen- to thirty-four-year-old segment of its audience, the managers at WBCN now turned to reassess the soundness of their air talent. “WBCN had been as important to Boston as the Globe and the Red Sox; we were an institution,” Oedipus observed. “But now, nineteen- and twenty-year-olds could no longer relate; they wanted something else.” The program director referred ominously to the sacrosanct “Big Three,” intact and in place on ’BCN’S weekday air since 1980. At the moment, Laquidara and Parenteau were winning their respective battles, even with the younger listeners, but a shadow of scrutiny had now fallen on Shelton’s shift. “Oedipus called me one day and said, ‘I need to talk to you after your show,’ the midday man recounted. “He said, ‘You’ve been great and we love you. It’s been such a perfect fit, gliding from Charles’s insanity to Parenteau’s wildness, the calm between the storms. But the company just bought WZLX, and there’s a big master plan; there’s going to be lots of changes.’” Shelton suspected what was coming next: that “master plan” probably included moving some or all of the ’BCN old-timers over to the classic rock station. “Oedipus said, ‘You’re the highest-paid midday guy in America. Your contract is up in a year; you’re welcome to stay and keep doing what you’re doing. [But] Mel loves you; he thinks you could be a [good] morning man. How about doing mornings at ’ZLX, with more money?’”

Shelton maintains that his relationship with Oedipus and Tony Berardini had curdled by that point over a union matter concerning insurance coverage: “They hated me and I hated them.” Oedipus, however, saw it as strictly business: “It happened to Shelton: for an eighteen-, nineteen-, or twenty-year-old [listener], he was now their dad’s DJ.”

“They would have fired me right away if I didn’t have the guardian angel, Mel Karmazin, sitting on my shoulder,” Shelton countered. The jock walked away from his long-standing midday home in July of ’93 to assume morning drive-time duties at Infinity’s new classic rock acquisition. Despite the bad blood that had spread between the players in this episode, the move was strategically sound and mutually beneficial. The older WBCN listeners who loved “Captain Ken” for all those years would now follow him over to WZLX, where he played the legendary songs they enjoyed, while Oedipus was now free to replace him with someone he saw as a better and younger fit for the station’s changing image (currently under construction). The ironic element was that Shelton now competed for listeners in the same time slot as his buddy Laquidara, the radio maniac he had clowned around with during “Mishegas” crossovers for well over a decade.

With Shelton’s departure/ouster, Bradley Jay, a veteran of various shifts at WBCN since 1982, moved into the midday slot. Although now a twelve-year veteran of the station, the DJ possessed the hunger and image of a much younger and savvy new-music-oriented jock. With his unquestioned enthusiasm, Jay had proved to be resilient in whatever role Oedipus asked him to perform, from famously clowning around backstage with David Bowie and hosting Lunchtime Concerts in the eighties to playing a controversial figure in a salacious evening show before Howard Stern replaced him. Jay had moved into the night shift in ’92 with the challenge of trying to head of the slide of listeners, not only from ’BCN, but also from radio in general, which occurred right after drive time. “Oedipus said to me, ‘I want you to go for it, do things to make people notice,’” the jock remembered. In the quest for ratings, perhaps inspired by the success of Stern’s show in other markets, WBCN went where it had never gone before: into R-rated territory. “We called the show ‘The Sex Palace’; it was the Howard Stern show, but Howard wasn’t there yet. We had strippers dancing in the window on Boylston Street, stopping trafc!” The lascivious spectacle, described on the air in every detail, drew a large crowd of listeners and pedestrians, who might have been stunned at the tawdriness of the moment yet remained to gawk at all the undulation, where, just eleven years earlier, Tony Berar-dini and Marc Miller had solemnly addressed hundreds of John Lennon mourners.

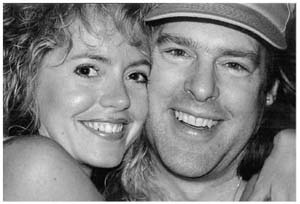

Bradley Jay and Tami Heide get close for the camera. Photo by Roger Gordy.

“ ‘The Sex Palace,’ was a little ‘out there,’” Oedipus admitted. “It worked for a while, but Bradley just couldn’t make the show broad enough, intriguing and risqué enough, to draw in a large audience like Howard Stern. [He] couldn’t quite pull it in.” When the program director and Tony Berardini took the monumental step of importing the actual master of that game, Jay was left without his full-time shift. “I didn’t freak out, I didn’t get bitter, I didn’t burn bridges.” He left for Los Angeles but only stayed away for a few weeks before returning to do more part-time shifts. But during that brief period away, the jock redefined his radio approach. “I read this book on marketing that said if you have a product, like mouthwash, and there’s already a Listerine on the market, don’t make another product that ‘kills germs’; make it different. There was already a Howard Stern, so it was pointless to be a shock-jock; I did the exact opposite and went minimal.” As the buffer between the up-tempo mischief of morning and afternoon drive times, the music orientation of the 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. shift had always been the correct recipe for success at ’BCN, and Jay poured himself willingly into the mold. “That seemed to be attractive [to Oedipus] because that is how I pretty much eased into the midday.”

The next step was the music itself. Never a stranger to presenting the latest records and new bands, WBCN by default had always featured an ample variety of new music. By mid-1992, the station regularly played the music set free by Nirvana’s hydrogen-bomb-like arrival: Seattle “grunge rock” and its major purveyors, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, and Soundgarden. The later, more commercial “postgrunge” bands such as Stone Temple Pilots and Bush found a home at WBCN, as did the “Brit pop” groups like Oasis and Blur. These exciting new sounds were featured freely next to mainstream acts like the Rolling Stones, The Who, and Pink Floyd. “We were playing the stuf we loved,” Bill Abbate mentioned, “Pearl Jam instead of the latest from Huey Lewis and the News. It was new, it was fresh, and it was fun.” In 1997, the industry tip sheet, MQB —Modern Quarterback, quoted Oedipus about the change: “’BCN had been defending its upper demos from ‘ZLX by leaning hard on its classic rock library. ‘It was time to let the classic rock station succeed on its own terms; there was no reason to fight them anymore.’” Steve Strick (who had become assistant music director by this time) agreed: “We already had a classic rock station in town; why go against them and split an audience that was not growing, but perhaps, dwindling in size? Everybody in the room was leaning toward the younger, more modern route. It was a more exciting direction to go, and even Tony went along with it, because he saw it as a way for the station to evolve and grow. We decided to do it gradually: playing the new music and starting to weed out the artists who were incompatible.” Strick smiled and added, “So every week [in the music meeting], there was this fun little exercise of eliminating another artist. One of the first to go was Jethro Tull. Everybody was jumping up and down, ‘Great! Snot dripping down his nose—get that of!’ We stuck with a few, but it took about six months to rid the station of the older stuf.”

Steve Miller in the studio with Mark Parenteau, also producer Jef Myerow. Changing times and a younger-oriented format soon leaves artists like Miller behind at WBCN. Photo by Mim Michelove.

A WBCN playlist from June 1993 included new music artists—Stone Temple Pilots, Porno for Pyros, Radiohead, Frank Black, Alice in Chains, and Soul Asylum—but was dominated by the latest singles from classic names like Rod Stewart, the Steve Miller Band, Pat Benatar, Donald Fagan, Pete Townshend, Van Morrison, and Neil Young. Nearly two years later, in April 1995, another sample playlist revealed that ’BCN’S transition had been completed: artists such as Green Day, Live, Offspring, Morphine, Filter, Oasis, Pearl Jam, Belly, and Matthew Sweet completely commanded the roster, the sole classic entrant being Tom Petty and his song “It’s Good to Be King.” This development prompted Jim Sullivan in a May 1995 Boston Globe article entitled “Reinventing the Rock of Boston” to declare, “AOR is dead. Or dying. Or mutating. Oedipus wants nothing to do with those three now-dirty letters. ‘WBCN,’ he says, ‘is a “modern rock” station.’” Sullivan also pointed out that this shift to play alternative sounds was a national trend, with several of the approximately 175 album-oriented rock (AOR) radio stations making the switch to play alternative music and join the 64 or so modern rock stations on the other side. “ ‘We’re redefining the center,’ says Oedipus. ‘The center will not hold; it’s very askew.’”

In Sullivan’s article, Oedipus admitted that the transition from full-on AOR to a modern rock entity took well over a year to complete, but the experience of attending Woodstock ’94 “gave it a big kick.” That festival, a twenty-ffth-anniversary tribute to the original three days of peace, love, and music that helped mightily to transform a generation, was held 12–14 August 1994 in Saugerties, New York. Santana, Joe Cocker, CSN, and John Sebastian returned to encore their now-mythical performances from the first concert, joining other classic rockers like Bob Dylan, the Allman Brothers Band, Trafc, and Aerosmith. The cream of the modern rock movement also mounted the two main stages at Woodstock: Nine Inch Nails, Green Day, Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Cranberries, and many more.

As a player during the original festival and still in business to enjoy the vibes a quarter century later, WBCN’S presence in upstate New York was a must. “’BCN had the foresight to rent this house, a kind of cheesy ranch house which, for some reason, smelled horribly like fish,” Bradley Jay remembered. “You could hear the bands in the distance, and you could walk there.” The place ended up being called “The Love Shack,” and the crew from WBCN used the house as a base for its broadcast operations during the rainy weekend. “I was there early, but the day the show started, people started to roll in. Oedipus had decided that we were a station of the people, and he made sure we broadcast that everyone should stop by ‘The Love Shack’ on their way to the festival. So they came all the time, even in the middle of the night, like zombies! They’d be knocking at the door, [saying] ‘We heard on the radio we could stay here.’”

“We got inundated with people,” Albert O agreed. “Parenteau suddenly showed up, John Garabedian was in there, J.J. Jackson, this woman Kat who worked at ‘FNX at the time.”

“It truly was ‘The Love Shack,’” Jay commented. “At one point I got up in the middle of the night to use the bathroom, and it was like a Monty Python skit: every room, every bunk, everything, and everywhere: sex was going on.” Vegas rules applied: what happened at “The Love Shack” stayed at “The Love Shack.” Jay added, “It was good times there, till the people from MTV came in to use the bathroom and clogged it up!”

Never buoyed by an explosive political undercurrent, nor a joining of voices against an unjust war, nor a historic gathering of “freaks,” the Woodstock ’94 festival nevertheless contained some terrific musical performances and assembled a massive number (over three hundred thousand) of WBCN’S revised target demographic: eighteen- to thirty-four-year-olds. For Oedipus, the experience proved to be as vital as it was enjoyable, serving as a research project in a gargantuan test market. Thousands stood in what became a muddy mess as the skies constantly hemorrhaged, but the overwhelming preference of the crowd for this new music confirmed to the program director that the fresh direction of the station was the correct one to take. Oedipus marched back from Woodstock all fired up. He was waiting for Steve Strick and me when we got into ’BCN to begin our workweek. Breathlessly, he described his experience and then began discussing whether we should accelerate the process of removing classic artists and adding modern ones to the playlist. We decided to experiment by going 100 percent modern rock on the weekends, a gutsy move considering that there were no focus groups, no strategic studies, and no call-out research to add to our gut instincts. But, within weeks, the ratings on those Saturdays and Sundays had improved so much, so fast, that we had to look at each and admit, “What were we waiting for?”

“We are definitely the New Woodstock station,” Oedipus told Jim Sullivan in his ’95 Boston Globe piece. “WZLX is the Old Woodstock station.” The article went on to acknowledge that in a half year of programming modern rock, WBCN had lost ground to WZLX in the 25–54 audience, but (as intended) “in the younger 18–34 male category, [WBCN] significantly increased listenership over WZLX and WAAF.”

With Ken Shelton gone, Bradley Jay in the midday seat, Howard Stern on at night, and modern rock the format, ’BCN headed into 1995 as a rein-vigorated fighting machine. But the new music, as refreshing as it might be to the air staff, came to the station with a price. Because it was key to create hits out of these new songs, anchoring the format with the most powerful and coveted tracks, WBCN began playing its strongest music in a rotation of five to six “spins” a day. With that, the opportunities for the DJS to add their own optional songs (a tradition of varying freedom over the years) had ended completely. Now, the only musical freedom that could be exercised by an individual member of the air staff was if he or she attended the music meeting and voiced an opinion. “It was a slow evolving of complete freedom to gradual acceptance, and by ’95 it was really tight,” acknowledged Mark Parenteau. “I had started out way back making no money with 100 percent freedom; now I was making a quarter-million dollars [a year] and I had no freedom. But, it was a trade-of I gladly gave them.” Most of the jocks, though not making anything near Parenteau’s pay scale, had to agree that it was much more fun playing the music they enjoyed the most, even if the ability to choose individual tracks during their shifts had been curtailed. “Lots of people, from U2 to the new artists, were turning out great records,” Steve Strick said. “It was a no-brainer to tap into that youthful energy.” It also resonated with WBCN’S past, which had always embraced the new and revolutionary, the up-and-coming, and the future trendsetters. “A roster once clogged with Classic Rock bands (Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd) now churns out a steady diet of new-rock acts such as Belly, Liz Phair, Oasis and Bush,” Dean Johnson wrote in the Boston Herald in May ’95. He concluded, “There was a hole in the Boston market for a new-rock/alternative music station with a major FM signal. There is no hole anymore—and WBCN will reap the rewards.”