AS HE HIMSELF is usually the first to point out, genial Harry Warren is probably the most successful composer of popular music who has ever remained completely unknown to his vast American public. For nearly half a century, generations have hummed to, sung to, danced to, wooed and won wives to, bellowed in the shower and even marched to such Warren melodies as “Nagasaki,” “I Found a Million Dollar Baby in a Five and Ten Cent Store,” “That’s Amore,” “Jeepers, Creepers,” “The Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe.” And for all those same years the spotlight has stubbornly avoided round, five-foot-tall Mr. Warren.

Philosophic in his anonymity, pushing eighty, Warren is not completely reconciled to it. He has developed a certain snappish defense mechanism. “I never had publicity,” he says. “And now I’m at the stage where I don’t give a damn.”

As remarkable as the lack of Warren’s personal fame is the extent to which his songs remain firmly imbedded in the mass consciousness. Even today, among the latest generation of the early ’70s, those bushy-haired, granny-glassesed, passionately intense film devotees, there is keen awareness of Warren’s songs. The Elgin Cinema buffs and the Cahiers du Cinéma crowd may not recall his name, but they can all discuss his catchy ditties for such landmark early musicals as 42nd Street, Gold Diggers of 1933 (as well as 1935, 1937, and in Paris), Footlight Parade, Dames, and a dozen-odd other vintage Warner, Fox, and Goldwyn oeuvres. Camp he may be to the children; to their grandparents he has been a Pied Piper ever since that long-ago year of 1922, when his first hit song, “Rose of the Rio Grande,” was knocking ’em dead in vaudeville.

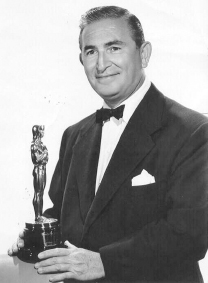

Harry Warren

Bing Crosby, Al Jolson, Fred Astaire, Judy Garland, Alice Faye—name a star performer, pick your favorite, and there’ll be Warren standards galore in his or her repertoire. So how is it that such deafening silence surrounds the composer?

Harry, who shows no sign of age beyond his snowy white hair, ventures an explanation. “I’m a Capricorn,” he says. “They call the Capricorn the hard-way guy, you know, you always have to go the hard way. If there’s a hot-dog stand and there’s a lot of people standing around and I keep saying, ‘Give me a hot dog,’ he probably waits on everybody but me, and finally when it gets to me, he says, ‘Wait your turn.’ Even when they had the ASCAP show in New York at Lincoln Center, I arrived in a tuxedo at the door, and the fellow stopped me. He didn’t stop the other people. He stopped me. He said to me, ‘Where are you going?’ I said, ‘Where the hell do you think I’m going?’ That’s the story of my life.”

But he’s not gone completely without recognition. What about his three Oscars for best film songs?

“Ah, I use ’em for doorstops!” Warren grins, lighting up a thick black Italian stogie.

It is a damp California morning with fog still shrouding the foothills above, and that same air that Harry Warren has been breathing since those days back in 1932 when he and Al Dubin were pounding out hit songs for Busby Berkeley to stage is now slightly acrid with smog. Warren still maintains a large home, early ’30s style, off Sunset Boulevard, in Beverly Hills. Some yards away is his work studio, and here is his piano. He snaps on a small gas heater to warm up the room. “So, you really want to take about me?” he says, with amiable sarcasm. “Isn’t it a little late for that?”

Can he perhaps explain how so little personal recognition has accrued over the years to his massive output of melody?

“Well, I never was a publicity seeker,” he admits. “They always wrote about the guys were publicized. Like, the other day this guy comes to me and interviews me about Burt Bacharach. Like he’s the second coming of Jesus. He’s telling me this guy has just upset the whole music world. I said, ‘No! He’s just getting a lot of publicity.’ Another thing, he’s an entertaining songwriter. He’s an actor songwriter. He goes out and plays his songs with a big orchestra. Have you seen any songwriter doing that, except maybe Mancini? He and Mancini, they’re the only two. It’s like the old days, when Johnny Mercer used to go on a lot of radio shows. So did Hoagy Carmichael. They got publicized. Years ago, when Berlin had his own publicity department, with his own company, he did the same thing.”

The walls of the small studio are covered with framed photos: a much younger, black-haired Warren pounding the piano, Dick Powell leaning on his shoulder, reading the music. Affectionately inscribed photos of Al Jolson, Alice Faye, and Warren’s later collaborators, Ira Gershwin, Johnny Mercer, Dorothy Fields. “So many people out here did so much,” he murmurs. “Look at little Leo Robin there. You ever hear anybody mention him?”

It is a pleasure to inform him that Mr. Robin has supplied fascinating material for a section of this book dealing exclusively with his accomplishments. “And of course he won’t take bows for anything he did,” says Warren. “You know, I nicknamed Leo the Mary Pickford of the songwriters.”

Against another wall is an elaborate tape system on which Warren plays his favorite music, notably the works of Puccini. “My favorite composer,” he says. “Not just because I’m of Italian extraction but because he was such an innovator. I just love his music.” There hangs a framed sheet of one of Puccini’s original manuscripts. “They presented me that when I was on This Is Your Life,” he says, caressing it with affection. “Sometimes I go off on a Puccini kick for days. I’m also hooked on Der Rosenkavalier. You know that was Jerry Kern’s favorite opera? He got me started on it. I used to say you’d have to have buttons in the belly to sing Richard Strauss’ music. I don’t know how the singers did it, because sometimes there isn’t even a cue note for them. They have to hit it like that. You know who’s great at that? Bing Crosby. He knows just where to come in. You never have to give him a ‘da’ to tell him where he has to start singing, he just knows.”

How did he get started writing songs? What was the impulse?

“Oh, I always had it. It’s a craving, says Warren. “My family was the same; my sister was in show business, my brother was a singer, and I always wanted to learn to play an instrument. But we didn’t have the money for me to learn to play one, so little by little I started saving money. My father was a bootmaker, he felt you should have a trade. But by the time I was fourteen I was a drummer in a band. Snare drum and bass drum. I got a job in Canarsie: you know where that is? That’s the roughest end of Brooklyn. Played in a dance hall. Oh boy, that one-o’clock train leaving Canarsie, it was a corker. One long blast of the whistle, and at the next station the whole platform would be lined up with cops with their clubs out.

“You know, sometimes I can’t realize how old I am. Look at all the things I’ve done. I worked at the Liberty Theatre in Brownsville when Jacob P. Adler ran the Yiddish stock company there. I used to sell fruit, you know, walking down the aisles and everybody clamoring to buy an orange or a lemon, and everybody with tears flowing from the melodrama up on stage. I remember a guy there who was the cop, Hymie—he became the Democratic leader of Brownsville, this guy. Couldn’t read or write. When the lights went down before the curtain, he had a cane, and he’d go around the theatre and hit people in the back and yell. ‘Hats off!’

“Then I got a job at the Loew Theatre on Liberty Avenue as a stagehand. Twelve dollars a week. Saw all the vaudeville acts. They used to have little signals, you know, for actors that didn’t tip us stagehands. Guys lifting their trunks to take them out at the end of a date, they’d tie a shoelace to the trunk. When the act got to the next theatre and the next stagehands saw the shoelaces, they’d know this bum didn’t tip. So anything that vaudevillian would ask for, he couldn’t get!”

That was before World War I. When the unions came in to organize the stagehands, Warren went on to other pursuits. By now he had picked up a little piano playing. He found a job at the Vitagraph movie studio in Brooklyn and graduated to the rough-and-ready job of assistant director. He also became unofficial pianist for Corinne Griffith, a reigning star of the silents. While Miss Griffith emoted for the camera, Warren would improvise background music to create the proper “mood” for her dramatic scenes.

“From that, I got a job playing in silent movie houses. Out in East New York there was a movie house where I got $12 a week. They used to pay me off in nickels and dimes. Weighed a ton. I used to get on a trolley car with one half of me lopsided.”

Came World War I, and Warren joined the Navy. He was stationed at Montauk Point Naval Air Station, where he was assigned to play piano and to lead a small band. “A flying piano player,” he remarks. After the war ended, he returned to the local cafés. “I didn’t play so good,” he admits. “I still don’t play well. I play better than Berlin, though. And Jerry Kern, too— I play better than he did. Cole Porter was a lousy pianist. Anyhow, one night two guys came into this place, they were a little farshnashkied [Brownsville Yiddish for drunk], and we got talking. I found out they worked for a music publisher and I said, ‘Gee, I got a song,’ like that. I had written one called ‘I Learned to Love You When I Learned My ABC’s,’ which is my pet songs even now. So they heard it and asked me to come play it for their boss on Monday. That’s how I got my first job, with Stark and Cowan Music Company. Twenty a week. I was in the music business! But my song didn’t get published because just that week Woolworth’s, a big outlet, decided to go out of the sheet-music business, and that sort of put an end to things for a while. They’d give me a paycheck and say, ‘Don’t cash it till next Tuesday.’ My next tune did get published—‘Rose of the Rio Grande.’ Became very big. But I never collected a nickel royalty. They gave me a promissory note on it, and by the time the note came due, the bank had folded!”

Warren went on to learn the niceties of composition very quickly. “I learned the mathematics,” he says. “That’s all music is—mathematics. I asked questions along the way. You had to learn. You had to transpose. How else could you play songs for big acts like Sophie Tucker and Belle Baker and all those people you needed to plug your songs?”

During the mid-’20s Warren’s melodies began to achieve a certain steady acceptance. He wrote “I Love My Baby, My Baby Loves Me” with Bud Greene, as well as “In MY Gondola” and “Nagasaki,” and soon began to find a niche on Broadway, writing for sophisticated revues. By 1930 he was writing with Ira Gershwin and others, and composing the melodies for “Cheerful Little Earful” and “Would You Like to Take a Walk?” with Billy Rose and Mort Dixon for a show called Sweet and Low. The following year, for Rose’s show Crazy Quilt, there emerged “I Found a Million Dollar Baby in a Five and Ten Cent Store.”

Warren had ventured westward in 1929 to work on a film called Spring Is Here, notable only for the song “Crying for the Carolines,” but he quickly returned to New York. “I couldn’t stand it here then,” he admits. “I missed Lindy’s. This place was nothing. Then I came out in 1932, to do another picture. Al Dubin was already here; they’d assigned me to work with him.1 Summertime. The studio was closed. Probably only two or three writers on the Warner lot, nobody else, and Zanuck was running the production department; he had an idea about making a picture, but he didn’t know what. A something. He was going to make something with music. Of course, musicals were dead at the time. And Warners was in a lot of financial trouble. So was everybody else. Zanuck got a set of galley proofs of this book called 42nd Street from the New York story department, and he read it and said, ‘I think this would make a good musical. Why don’t you stay on?’”

Warren shakes his head. “Burbank in the summertime. No buildings anywhere, just fields. It was like being at an Indian outpost. Hotter than hell. No air-conditioning.

“Dubin and I sat down and we wrote this score practically from the galleys. They had Dick Powell, and Zanuck told us he was putting Jolson’s wife, Ruby Keeler, in it, and they had Buzz Berkeley sitting around, so we sat down and began to write songs. ‘You’re Getting to Be a Habit With Me,’ ‘Young and Healthy,’ ‘Shuffle Off to Buffalo.’ Afterwards they wrote the screenplay. Of course today Berkeley tells everybody he told the writers what to write … but you know”—Warren winks broadly—“you never heard of a dancer or a choreographer telling anybody what to write, did you? He used to sit down on the stage for days with about a hundred girls, waiting for us to write him something.”

Did Warren and his partner Dubin have any idea that this modest film was going to become a landmark? That it would go on to be a huge financial success, to revive the public’s craze for film musicals, to earn so much profit that the film’s returns would rescue Warner Brothers from near bankruptcy?

Warren shrugs philosophically. “Not at the time. Who knew? We just worked hard. I remember Al Dubin—he was a terrific eater, weighted about three hundred pounds—he’d disappear on me. Carried a little stub of a pencil, wrote lyrics on scrap paper. I’d write a tune and hand him a lead sheet and then I’d never hear a word. All of a sudden, he’d come back and he’d have the lyric. Once he brought in ‘Shuffle Off to Buffalo’ on the back of a menu from a San Francisco restaurant! There weren’t too many good restaurants here in those days. I always say that with all the wonderful ones we have now, if Al were only alive he could be doing some great lyrics!”

The Warner lot of smaller then, more compact, everyone more cooperative, especially in the face of the dire economic adversity that loomed everywhere outside those Burbank sound stages. “It was something like a stock company,” remarks Warren. “Even though the Warners could be cruel in some ways. I remember later, when we were doing Gold Diggers of 1933, we’re sitting in the projection room and they ran our number ‘Remember My Forgotten Man.’ Now, we’d thought that number up out of the blue, which we had to do all the time. It’s like writing for a revue, you know— you had to get ideas. Berkeley had done a great job on this. And they’re all sitting in the projection room, Mervyn LeRoy and Mike Curtiz and all of Zanuck’s cohorts and Jack Warner, and then the lights came up. Everybody is raving about this number, and Jack turns around to me and Dubin and he says, ‘What’re you guys doing here? You were laid off last week!’2

“We thought he was kidding. But we were laid off, and we didn’t know it yet! Another time Bill Koenig, who was studio manager, called us in and asked us to take a cut. I was getting $1,500 a week—darn good dough in those days. The money was the only real reason I could stand staying out here in California. I said, ‘Why should we take a cut?’ and he says, ‘We’re losing money.’ I said, ‘Not on musicals!’ He says, ‘Forget it.’”

The roster of Harry Warren—Al Dubin scores bears ample witness to the composer’s angry retort. 42nd Street was followed by Gold Diggers of 1933, then an Eddie Cantor film for Sam Goldwyn, Roman Scandals, and Footlight Parade. In the same year, when Zanuck departed Burbank to form Twentieth Century, the team wrote the score for his first independent musical, Moulin Rouge.

In the following year, 1934, the team churned out scores for Twenty Million Sweethearts, Al Jolson’s Wonder Bar, Dames, and Sweet Music, which starred Rudy Vallee. And in 1935 their output was truly prodigious. No less than eight Warner musicals featured huge phalanxes of beautiful girls dancing and singing Warren-Dubin tunes. Rarely did they turn up with fewer than two hits in any of their films. In Gold Diggers of 1935 they won the Academy Award for “Lullaby of Broadway.”

“I guess we made an impact all right,” Warren admits. “It was thirty, forty years ago; you don’t remember those plots, but the songs still hold up, don’t they? They still play ‘About a Quarter to Nine,’ from Jolson’s Go into Your Dance, and ‘I Only Have Eyes for You,’ and a lot of the others, all alive, still alive. Funny, though, we did all the pictures, made them all that money, but in most of them they never even mentioned us. Publicity? Nothing. But, as I told you, I never looked for it …” He lights up another stogie.

“But then we went to Europe with Buddy Morris, who was the head of the Warner music publishers—he and his wife, my wife and I, and Benny Goodman—and we were at the George V Hotel in Paris. They sent a sound truck over to the hotel and did a big interview on the radio. They knew all about our musicals over there, they were big fans of the composers already. Not only the French, the Germans too. After Hitler came in, every refugee who came here from Germany who was a music-writer knew me. They’d call me up and want to meet me—because they had seen those musicals!

“Maybe I should have gone and played piano at producers’ parties. That’s how you got attention out here. But the hell with that. I’m a family man. Always was. Most guys who got ahead in the picture business lived like single men, even if they were married. Played cards with the boss, went to the tracks, partied. But not me. I always came home. I didn’t go out nights. You know, I’ve been living here since ’32, forty years, and I never went to a Hollywood party?

“And sometimes somebody would say, ‘Did you write “Lullaby of Broadway,” really you?’ I got that with all my songs. ‘Now, don’t tell me you wrote that one too?’ But that was all part of the game. Out here in Hollywood a songwriter was always the lowest form of animal life. Unless, of course, you were a Broadway show-writer. Then they paid you respect. I remember once in the café at the Warner lot Eddie Chodorov was there. He was a Broadway playwright, and he was explaining something to Jack Warner with a few of those college expressions he had. And Jack Warner, after he left, said, ‘Smart guy, great guy!’ See, the guy had gone to college. Jack never went. He was impressed by Eddie’s education. And that’s a throwback from the old days. My father always said, ‘You tip your hat for the doctor.’ I’m of Italian descent; with us it was a tradition. My father had great respect for anybody who was a professional man, a lawyer, a doctor. You tipped your hat—that came from the old country. The judge, the doctor. You kissed your midwife’s hand too, you know. That’s a mark of respect for the woman who delivered you. So I guess the respect these guys here had for the Broadway show-writers was probably part of the same tradition.”

Warren stares out the window for the long moment. The morning sun is about to break through the dense gray landscape; bright light is beginning to spread outside, revealing broad lawns and colorful flowers. “Most of those guys were illiterate, anyway,” he murmurs, calling back his memories. “I could tell you such stories. I remember when Hal Wallis was producing Hollywood Hotel and I prevailed on him to hire Johnny Mercer and Dick Whiting to do their first picture for him. Very talented men. So Wallis calls me after. ‘Come on down, I want you to hear their songs.’ I said, ‘Hal, don’t ask me to go down and pass on their songs, that wouldn’t be right. I’m not the producer; you’re the one to decide.’ He said, ‘But you told me to hire them!’ He didn’t know. That’s what you were up against.

“We had a waltz in a picture, Broadway Gondolier. It was called ‘A Rose in Her Hair.’ We played it for Wallis and he said, ‘I’ll bet it only took you five minutes to write that one, didn’t it?’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘It’s very short.’ I said to him, ‘What do you mean? It might take five days to write a short song! That’s got nothing to do with it!’ But, you see, they didn’t know….

“We had another song, called ‘With Plenty of Money and You.’ Wallis came to our bungalow, walked in. He picked up a newspaper that was lying there and he says, ‘Okay, play me the song.’ So I said to him, ‘Are you going to read or are you going to listen to the song?’ He said, ‘Come on, play me the song.’ SO we played it for him, and he got up and threw the paper down. He says, ‘It stinks. Write a new song.’ And he walked out. So I opened the door and I said, ‘You stink! Get a new boy!’ He turned around and laughed, but he kept on walking. So now we had to figure, how’re we going to get the song in the picture? Well, we knew there was another way we could do it. We knew Jack Warner and Hal Wallis were feuding. So we called Scotty, who was Warner’s secretary, and we told him we had a song we wanted J.W. to hear. He calls back and says Warner wants us to come right up. So we went up and said to Warner we wanted him to hear a song that Wallis didn’t like. We played it. He said, ‘That’s swell! What the hell does he know about songs? Great, it goes in the picture!’ That’s how the song got into Gold Diggers of 1937.”

He chuckles at the recollection. “Big hit. Opened the picture. Depths of the Depression. Marvelous idea in the title—‘Oh, Baby, what I couldn’t do, with plenty of money and you…. ‘ But those were the little devices. We had to do that in reverse, too. With Wallis. We’d go to Warner and play him one, and if he didn’t like it, we’d play it for Wallis and tell him Jack didn’t like it. Again, in it went!

“Illiterates, you know? Illiterates in that they didn’t know whom to respect. I grew up knowing that you respected talent, no matter who had it—it could even be the stagehand or the electricians. You know, I was very close friends with Jerry Kern, who was working on the Metro lot before I went there, years later. And he was getting something like $3,000-$4,000 a week. And David Selznick, who was then head of his own unit there, was going to do a picture called Ebbtide. He sent for Jerry; Jerry had a bungalow at Metro. He came in. Jerry was a little martinet, you know. He always had his coat buttoned in the wrong place, and he always had his sleeves rolled up, and he always cocked his head this way, on a slant. And Selznick said, ‘Mr. Kern, I’m doing a picture called Ebbtide. Play me some melodies.’ And Jerry looked at him and he said, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t play samples.’ Walked out.

“There was another guy, I think it was Pandro Berman, who was producing Roberta at RKO, before this, and Jerry had a song—it was called ‘Lovely to Look At’ after Dorothy Fields set the lyrics to it. He came in and played the melody for Berman, and Berman heard it and said, ‘Isn’t that kind of short?’ Jerry looked at him and he said, ‘That’s all I had to say.’ Ah, Jerry, he was fantastic…. ‘That’s all I had to say.’”

Al Dubin died tragically young, in 1945. By that time Warren had left Warners and moved his piano over to 20th Century-Fox. But before he departed Burbank for West Pico Boulevard, he did a set of songs with young Johnny Mercer, the talented lyricism he had recommended to Hal Wallis. One of their creations, introduced by Louis Armstrong in a Warner remake of a play called The Hottentot and renamed Going Places, was the joyful “Jeepers, Creepers.” And for an equally forgettable film called Hard to Get they produced “You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby.” Later he and Mercer were to team up again with equal success. But when Warren moved to Fox, it was to work with another king-sized gourmand, the legendary Mack Gordon. From 1938 up to and throughout the war years came a seemingly endless string of Darryl Zanuck’s musicals, equipped with Alice Faye, Carmen Miranda, Sonja Henie, Betty Grable, Tony Martin, Don Ameche—and Gordon-Warren tunes.

“Funny, all those years I never felt like a native Californian. Lots of times I’d think about throwing it all up and going back to New York. You know, in the old days here we would say, ‘Don’t buy anything here you can’t take with you on the Chief’—that was the train that took you back East. So we never bought anything. We could have been millionaires with real estate; we never gave it a thought. Property on Rodeo Drive that was $10,000-$15,000 a lot—today it’s worth millions. But it always was that kind of a business to me—it never felt permanent.”

Whether or not Warren personally felt stable becomes irrelevant when one runs through even a partial listing of what he and Mack Gordon produced in their studio years at Fox. There were massive successes, such as “I’ve Got a Gal in Kalamazoo,” which Glenn Miller’s orchestra made permanent in Orchestra Wives, “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” lovely ballads of the quality of “You’ll Never Know,” “At Last,” “Serenade in Blue,” and “There Will Never Be Another You.”

The inevitable question becomes, did Zanuck know anything about musicals?

Warren’s answer is short and to the point. “Nope. Although he was great with songwriters. I’ve never heard him say—and I did a lot of work with him—‘That’s a lousy song, we can’t use it.’ Never. Though for some reason he was tough as hell with scriptwriters. But don’t forget one thing: we delivered. Hell, sometimes we were working on two pictures at a time. They used you. It was always, ‘C’mon, fellas, help us out, we’re in a spot here with the picture, put in a little extra time for us, you’re part of the family.’”

Such intense pressure-cooker-type atmosphere can often induce bursts of creativity … or force the complete collapse of the muse.

“Well,” says Warren, with the magnificent candor of one who has made many trips to the well and rarely come up dry, “you either have it or you don’t You can’t be trained, you can’t go to school and learn it. You get a script and you read it, and then your subconscious mind goes to work. When I do a picture, I must write reams of melodies. I might write maybe fifteen, twenty tunes before I get the right one, the one that I like. I write ’em and I think about one—I always try to get the tune first, because the lyric-writer can always fit the tune. If I don’t get anything, I go away. Sometimes I get them away from the piano. Then, when I get the one I like, I say, ‘I think we’ll use this!’ But I always know going in what I’m looking for. When I did An Affair to Remember for Leo McCarey in 1957—Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr—I knew I had to get some sort of a melody that would sound good with the old lady playing it on the piano, one that would sound almost classical. Well, I must’ve written about twenty-five tunes before I finally hit that one.”

In 1945 Warren once again moved his piano—this time over to Culver City, where he became enfiefed to MGM and its feudal lord, Louis B. Mayer. One of his first assignments was to do the music for a film called Yolanda and the Thief, notable now as then for the fact that Mayer had cast Fred Astaire opposite a complete unknown, Lucille Bremer, a lovely dancer whom the great L.B. had spotted in the chorus line of New York’s Copacabana. The results were disastrous. Yolanda and Miss Bremer faded into the sunset. Astaire and Warren survived Mr. Mayer’s momentary whim.

“Oh, sure, it’s fashionable to knock Mayer now,” says Warren with a flash of truculence. “But it’s easy to forget what a really good producer he could be. I thought he was great. He did more for musical pictures than anybody. He really liked music, and he liked to make musicals, and that to me was more important than these dramatic producers or another guy who wanted to make gangster pictures. He had a whole school of sopranos over there, all kinds of singers, vocal teachers, a stock company of singers and dancers. That lot was really jumping. I got the biggest salary of my life at Metro. Funny thing, though, the only song I ever scored with over there was in my next picture, The Harvey Girls, which I wrote with Johnny Mercer. Judy Garland sang it—‘On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe.’ Look over here….”

He jumps up, goes to the wall, removes an elaborate gold-encrusted plaque, and proffers it for display. “Out of a clear blue sky, this came last year. The president of the Santa Fe Railroad himself sends it with a letter. He says this is to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the song Mercer and I wrote. Sends a guy up here personally to deliver it. They took pictures. My God, it’s been twenty-five years!”

He replaces the plaque with care, next to the assorted photos of Bing Crosby, Dean Martin, Jolson, and framed copies of his own sheet music four and five decades old, all “standards” now.

“Maybe people didn’t like Mayer’s politics, or maybe that was just an excuse for not liking him, I don’t know which. I know one thing. If Judy Garland had been working at Warner’s you never would have heard of her again. First time she didn’t show up at a rehearsal or a date for something, Jack Warner would have taken her right off salary! He did it with Bette Davis, anybody. Anybody who argued with him—out! But Mayer was never like that. He used to send Judy flowers. And she cost them a fortune over there; a lot of people don’t realize that. We did a couple of pictures with her. She started on one called Summer Stock. Nobody knew where she was. She never showed up. And, you know, the day of shooting there could be a thousand extras there? They had to send everybody home and pay them. No explanation. You think she could have done that at Warners? Only with Louis Mayer….”

The opulent majesty that was L.B.’s domain, his glorious monolithic Metro, has long since crumbled. All that remains are the cans of film, and a few vivid memories of Mayer, the private property of veterans like Warren. “You know what he did to Robert Walker, who was quite a tippler in those days? He got him in there one day, and said, ‘How would you like to be an extra who lives way down in Hollywood and you have to get up at five in the morning and take three or four buses to get to Culver City and get out here to find out they’re not shooting because the star, somebody like you, didn’t show up?’ He said to Walker, ‘You’re depriving these people of their livelihood, their means of getting some food.’ Walker really cracked up at that. ‘Mr. Mayer, I never thought of that,’ he apologized. ‘Well, you should!’ said Mayer.

“Because back in those days, you know, if you lived out here, it was complicated to get from Hollywood out to Culver City. Or going out to work in the Valley. They used to ask me, ‘Harry, how come you never worked for Universal?’ I said, ‘I never did get a passport to get over there.’

“Oh, Mayer was a tough man, sure. After some years I figured I’d had it there and it was time to quit.” Warren had by that time crafted an excellent score with lyricist Ira Gershwin for The Barkleys of Broadway, which had reunited Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in 1949. “Fred, that’s another guy with great magnetism,” he comments, with obvious affection. “He isn’t vocally good, he hasn’t got a great voice, but there’s something about Fred—when he sings a lyric, it really comes out.

“To get back to Mayer. We were out on the stage, I think it was Summer Stock, and somebody called me and said, ‘Mr. Mayer wants to see you.’ I don’t know, I guess I kind of forgot about it. They were shooting a number, Gene Kelly was in it—I think it was ‘Dig for Your Dinner.’ All of a sudden, two cops come in and say, ‘Come here, Mr. Mayer wants to see you.’ And they grab me by the arm and take me up to his office. I didn’t know what the hell was up. So he said to me, ‘What is this I hear about you quitting?’ I said, ‘Well, I am, because it’s not a good lot for me. This is a songwriter’s graveyard here. You don’t get the plugs, your publishing companies are not good. We don’t get enough records on our songs, not enough noise is being made.’ It was the truth; I’d had much more success at Warners and Fox. So Mayer said, ‘I’m not going to let you quit. I’ll give you your own publishing company. How would you like that?’ I said that would be fine. But I didn’t realize that even when I had forty percent of it—and they had sixty—the same inefficient people who were handling the Metro music publishers would be promoting mine! It was just one of Mayer’s cute gimmicks!

“Later on, when it turned out that the firm I owned was losing money, we had a big meeting in New York. There were all the Metro lawyers and hatchet men sitting around, big cigars in their kissers, and one of them, the head killer, he’s reading the company report, like he’s a Supreme Court judge or something. He looks at me like I’m some criminal, and he says, ‘What are we going to tell our Metro stockholders? You know your firm has lost $150,000? What are we going to say to them?’

“He wasn’t kidding me,” says Warren truculently. “They could write that off. It was pennies. Lots of times people don’t think you know anything— you’re a songwriter, that means you’re a dope. But I said to this guy, ‘Tell them what you tell them when you lose a couple of million on one bad picture.’ He almost fell of his company chair.

“I don’t know exactly what it was, all that hostility toward us songwriters,” Warren continues, lighting another stogie. “Maybe it was because most of the time you were making more dough than the producer and he sort of resented that. He knew he needed you—that probably made him hate your guts all the more. The only guy that ever really gave us respect was Arthur Freed. He’d been a songwriter himself, and he knew. Hired the best people he could get, took big chances on young talent. I remember years ago he called me up, I was still at Metro, and he asked me to come over. ‘I got a couple of young kids coming in from New York. They’ve done some shows and they’re going to play me some stuff.’ I went over there and Vincente Minnelli was there, and a couple of studio people, and in walk these two guys from New York, with their little raincoats on, with horn-rimmed glasses; they looked like two little comics. They played a lot of tunes, and when they left, somebody asked Freed what he thought of them, and he said, ‘I think they stink.’ Alan Lerner and Fred Loewe! But here’s the point—right after that he was bright enough to see that he’d made a big mistake, and he reversed himself and hired Alan Lerner, who’s a great big talent. Matter of fact, I was supposed to work with Alan on Royal Wedding, but I was so busy on something else that they got him Burton Lane instead.

“Later on, a funny thing happened with me and Alan. I’m now out of Metro, and I’m sitting home, and the phone rings, it’s New York and Alan calling. He says, ‘How would you like to do a New York show with me?’ I said, ‘I’d love to.’ He says, ‘Don’t tell anybody—I’m splitting with Freddy Loewe—it’s a secret—and I want you to do the show. I’ll get back to you.’

“After that, nothing. Silence. Ten years go by. One day I’m over at Warners, looking for some sheet music I’d done there, and they tell me Alan Lerner’s there, recording the score for My Fair Lady—that’s the show he called me to do! So I walk down to the recording stage, and there he was. Alan’s a very European sort of guy. When he meets you, he kisses you. So he gives me a big hello, and I say, ‘Alan, you never called me back.’ He goes blank and says, ‘Gee, I don’t know what you mean.’ I say, ‘Don’t you remember when you called me up ten years back and said you and Freddy were breaking up and you wanted me to write this thing from Pygmalion into a show?’ He says, ‘oh, my God—Harry, you’re right!’ And I said to him, ‘Now, aren’t you glad you didn’t get me?’”

From Metro, Warren made still another move, this time to Paramount, where throughout the 1950s he continued to turn out successful film scores. For Bing Crosby’s film Just for You, he wrote “Zing a Little Zong.” And in the Martin-and-Lewis comedy The Caddy, he provided Dean Martin with “That’s Amore,” a hit song with firm Italian ethnic roots.

In 1956 he ventured back to his old stamping ground, Broadway, to write the score for a musical version of James Hilton’s Lost Horizon. Shangri-La, as it was retitled, proved to be a mammoth mistake when it opened in New Haven for its tryout. It was not Warren’s score, written with Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee, which was at fault; the physical production of the musical proved too massive and cumbersome for the stage. Shangri-La died a-borning, after twenty-one performances in New York. “Too bad, too,” says Warren ruefully. “I thought some of the stuff I had in there was as good as anything I’d ever written.”

Then came McCarey’s An Affair to Remember and a batch of scores for Jerry Lewis, in the days when that gentleman was still providing Paramount with a steady flow of blank ink for its corporate books. By the early 1960s Hollywood’s musical-comedy era was winding down after nearly three decades of all-singing, all-dancing profitability. Nowadays the original musical comedy, written directly for the screen, is a museum exhibit. Aficionados of the early Alice Faye/Don Ameche/Cesar Romero/Betty Grable/Dick Powell/Ruby Keeler era must sit up until 2 A.M. to hum along with their favorites on the Late Late Show, or seek out their favorite long-lost Carmen Miranda/Ritz Brothers/John Payne gaiety in some outof-the-way theatre dedicated to the renaissance of Zanukian musicomedy.

“Oh sure, the pictures may be old pieces of junk,” admits Warren, “but, damn it, the songs still go on. They have a sort of life of their own. Sometimes I hear them, and it brings back all kinds of crazy memories. Like when we were doing a picture at Warners for Clark Cable and Marion Davies. It was called Cain and Mabel. What a title! You know, Marion was a great girl. She always had music on the set. She had a piano, an organ, or something going all afternoon. When she walked on the stage in the morning with her little retinue of people, the orchestra would play something like ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ for her entrance!

“Anyway, we had to go over there to the stage to play some songs. One of them was ‘I’ll Sing You a Thousand Love Songs.’ Mr. Hearst himself was over three, and when we got to the stage, there were these two cops guarding the door. They wouldn’t let us go on the stage. So we went back to our bungalow. And we get a phone call. ‘Where are you guys? Come on over!’ I said, ‘They won’t let us in!’ ‘Come on over!’ We went over, the cops stopped us again! So we went back, and again they called us, and I said, ‘You go screw yourself! So we went back, and again they called us, and I said, ‘You go screw yourself! If you want us, you better tell those two cops to leave, or we’re not coming any more!’ We did another one for Marion called Hearts Divided. Dick Powell was her leading man in that one. He was scared stiff of doing love scenes with her; whenever they shot one, Hearst would be sitting right there on the sound stage watching, and Dick never knew whether or not the old man would get sore if he started getting ardent with Marion. A hell of a way to have to act, believe me! Anyway, when we wrote the songs for Hearts Divided, we had to play them for Hearst. He was in New York, and we had to do them for him over the telephone! I mean, what the hell can you hear over a telephone? He didn’t know what he was listening to, anyway. But he never turned anything down. Neither did the other producers. They took what we wrote, and onto the screen it would go. What the hell did they know? We were the ones who were coming up with the hits!”

*

The midday sun shines down on Beverly Hills. The canyons above, which were once covered with wild brush and populated mainly by animals running free in those earlier, less complicated days, are now studded with rows of expensive houses that march upward toward the flattened summits of the Santa Monica Mountains. Few of the inhabitants have anything to do with the business of film-making; those who do are involved with the sausage-style packaging of television half-hours, or with cable TV, video cassettes, and other visionary methods of making less taxable capital gains. Popular music has long since drifted away from the personality-cult era of Crosby, Astaire, and Alice Faye. We’ve come into a new world of LPs and college one-night concerts, performed by bearded bards with eight-stringed amplified guitars and folk-singing ladies with long golden hair who croon endless choruses of atonal anguish. And what does Harry Warren think of the musical scene, circa 1972?

“I think it’s awful,” he complains. “Mancini’s good, Elmer Bernstein writes good picture music, and Johnny Mandel, he’s great. But most of the rest of them….” he shakes his head. “They don’t do anything for me. I’d rather sit here and play my tapes. I can run the gamut of all music because I love music so much. I used to know all the overtures by heart. ‘Light Cavalry,’ ‘Poet and Peasant,’ ‘Morning, Noon, and Night,’ any one you could think of, I knew them all. I knew all the church music, all the Catholic mass music. I knew all the Debussy, I knew all the Ravel. I love them … and, of course, Puccini. I’m his slave. That’s music.”

We walk outside into the clear sunlight. Below us, behind a thick hedge, we can hear the steady rumble of that incessant California traffic. “Say, was I any help to you?” he inquires.

IN these past two hours he has footnoted forty years of Hollywood’s history. He is, in fact, a walking compendium of film history, this short, voluble gentleman who once played drums in Canarsie, who wasn’t completely sure that anything in Southern California was going to be permanent when he reluctantly stepped off the Chief back in 1932.

“History?” he says, beaming. “Say—I like that. I like being part of history. Think how many people live out all their lives and they’re never part of it. Just look at all the things I’ve done that have been a pleasure. Started as a drummer, then a piano player, then in the studios as an assistant director. I get to Broadway, I’m a song-plugger, then a composer. And then I come out here and I get to write a lot of hits with a marvelous bunch of guys I always enjoyed being around—Jerry Kern, Ira Gershwin, Johnny Mercer, Dorothy Fields, all of them. It’s been a hell of a good life, and I’m grateful for it.”

He tramps away toward a parked sedan, humming softly…. Obviously something from Puccini.