SAMMY CAHN’S New York abode—he still maintains a California residence—is an apartment in the East Fifties. But these days he is rarely very long at either place. He has friends in South America, in Europe, out in the Pacific, and he and his wife, Tita, spend a good deal of their time traveling. His world has expanded since the days when he played violin and told jokes with a pick-up dance band that specialized in weddings and Brooklyn bar mitzvahs. Later today he leaves with Mrs. Cahn to spend a month enjoying the Greek islands.

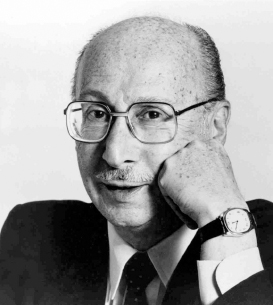

He has come to the door sporting an elegant flowered silk dressing gown, stylish garters holding up his socks. “Come in and let’s get talking, and I’ll take the phone off the hook,” he promises. “What do you want to know about me that everybody hasn’t already asked?” Whereupon the telephone rings, and he answers it by reflex, to tell a friend he can’t discuss anything because he’s too busy discussing something with somebody else. He is a garrulous man with a high-domed forehead and a tiny pencil-type mustache; his enthusiasm is cheerfully infectious.

He is also a very hard worker. He formed his first songwriting partnership back in the mid-’30s with Saul Chaplin. In California he worked extensively with Jule Styne in the World War II era and their collaboration turned out stacks of hit records. After Cahn and Styne wrote the score for High Button Shoes in 1947, Styne decided to make the Broadway scene his permanent beat. Cahn remained in Hollywood and began writing songs with other composers, finally teaming up with Jimmy Van Heusen. Cahn and Styne reunited, and won an Academy Award in 1954 for “Three Coins in the Fountain.” Cahn and Van Heusen won one in 1957 for “All the Way,” which Frank Sinatra sang in the film The Joker Is Wild. Two years later they won with “High Hopes,” and in 1963 with “Call Me Irresponsible.” Another of the Cahn-Van Heusen songs, “Love and Marriage,” which Sinatra introduced in the television version of Our Town, won an Emmy. Cahn and his collaborators have been identified with enough Sinatra hits— songs like “Come Fly with Me,” “My Kind of Town,” “The Tender Trap,” and “Hey, Jealous Lover”—to fill endless sides of Sinatra LPs. If Sinatra was—and still is—the King, then Cahn, Styne, and Van Heusen certainly have served him well as court composers.

Is it possible to document Sammy Cahn’s long career in the short space of time before he departs for the Greek islands?

Sammy grins. “Who knows? But we’ll never know unless we get started, will we?” But before he can begin, the phone rings again. His temporary presence in New York is obviously well known. He is here only for a day or so, but he draws calls as if he were the eye of a tiny show-business hurricane. This one is from a prominent night-club comic who’s made his debut in the film version of The Love Machine—it was shown privately the night before, and he wants Sammy’s honest opinion. (“Kid, you were great, but I have to give it to you straight—the picture is strictly dreadful. It’ll be a fight, but it won’t hurt you, it’ll help, you’ll get exposure with new audiences.”) Moments later there is another call; this time it’s a producer who wants to discuss a possible Broadway musical for Cahn. (“Sure, it’s possible, but not probable. How can I write lyrics on a Greek island? Besides, I’m too old and thin for those out-of-town arguments.”) Next there is a charity-show benefit chairwoman, a friend who desperately wants one of Sammy’s celebrated satiric song parodies to be performed on the night of her affair at the Waldorf. (“Darling, I can’t do it on such short notice even for you, but let me see if I can’t find somebody else to run up a couple of yards of jokes for you.”) And then somebody who wants Cahn to intercede for him on some matter with Sinatra. (“No way. He’s retired. Listen, I’ll miss Frank singing as much as you do. Probably a hell of a lot more, but you don’t argue with him when he’s made up his mind.”)

Between these phone conversations—he finds it somehow impossible to cut himself off from the outside world by taking off the receiver—the early days of Sammy Cahn manage to emerge in sporadic bursts of total recall.

Sammy Cahn

“I was born into the typical Lower-East-Side Jewish family, 1913,” he says, “and I had four sisters, and for some peculiar reason my mother insisted that I would play the violin. It seemed that in her mind the girl played the piano and the man played the violin. I guess she was scared by a John Garfield movie, or something.

“I didn’t like the violin, but I played it. I have a tremendous aptitude for music, and most of the credit I’m given for my lyrics results from my deep love of music. I can pick up any instrument, almost, and play it. I had a marvelous mother; she was the kind of lady you could make a deal with, which is what I loved her for. I made a deal with her—I’d play the violin until my thirteenth birthday, the fabled bar mitzvah. Sure enough, came the bar mitzvah, I played a violin solo, and that was the deal. Okay. Now, it was a typical bar mitzvah, and I had gotten all the envelopes from the relatives with the money inside, which is the way you pay for a bar mitzvah, and there was a little six-piece orchestra playing there, six guys having a good time, and at one in the morning my mother said the line which changed my whole life. She said, ‘Let’s go pay the orchestra’.”

Cahn shakes his head at the memory. “Pay those fellows for having so much fun? I didn’t comprehend it. They got thirty dollars for their night. One of them was Big Sam Weiss, who went on to play with Benny Goodman. Anyway, as we’re paying them, I asked them if they did a lot of this, and they said, sure, parties, dates. And I said, ‘Well, could I do this?’ and they told me, ‘Sure, if you want to.’ Two years later, at age 15, I was playing with the same orchestra, down on the Lower East Side.

“Can I tell you one of the greatest thrills of my life? Years later I’m at a party where Cole Porter is. Porter, Berlin—the two single most talented men in American music. Porter, my idol. Somebody says, ‘Cole Porter wants to meet you.’ I said, ‘Are you kidding?’ As I turned around, he came at me, Cole Porter, on those crutches, thin and small, and I didn’t know how to react to this—my idol coming up to me, I should have run to him. I just stood there, and he said, ‘Sammy Cahn, I’ve always wanted to meet you.’ I must have mumbled some kind of gibberish, like, ‘You want to meet me?’ He says, ‘I’ve always envied you.’ Envied me what? He says, ‘You were born on the Lower East Side. Had I been born on the Lower East Side, I could have been a true genius.’

“You know, songwriters are highly competitive people. They don’t really congregate with each other, like comics or actors. And with my feeling for Porter, oh well, to hear him say that—to me….”

Is there some mysterious reason why, consistently over the past half-century, the Lower East Side tenement neighborhoods have been the spawning ground for many of America’s most successful pop-music song-writers?

“That’s any ghetto,” says Cahn. ‘The ghetto is the cradle because the struggle is to get out of the ghetto. And in our country it comes in waves, along with the immigration. In the beginnings, the first waves, everything was Irish. The songs, the performers, comics—Harrigan and Hart, Eddie Foy, George M. Cohan, all Irish. Politicians, entertainers, writers, all Irish. Gangsters, prize fighters, all Irish. All right? Next wave into the ghetto, Jewish. Same pattern emerges. Singers, performers—Jolsen, Weber and Fields, comics, all Yiddish. Prize fighters, gangsters, Yiddish. Now it went to the Italians. Think hard—Italians. Performers—Sinatra, Vic Damone, Tony Bennett, Como. Politicians, writers, gangsters, prize fighters, all Italians, all struggling to get out of the ghetto. Now go on. The blacks are next on that ladder, the ethnic ladder, to get out. Now all the writers we’re reading—black. Performers—I don’t have to tell you about the music, the singers. The current wave is black. I don’t’ say I’m Margaret Mead,” concedes Cahn, “but that’s how it’s always seemed to me.”

The orchestra with which Cahn was to play did quite well, due, he claims, in large measure to Cahn’s mother. “She was a macher [maker]. Couldn’t read or write, but she became very big with the local Democratic machine. Got us a lot of work through her connections. Then I met Saul Chaplin. Can I tell you about that?”

Cahn beams with fondness. “We’re at the Henry Street Settlement House downtown, a wintry night, snowing, and I’d hired a new piano player from Brooklyn called Saul Kaplan. I was very anxious to see if he’d show up, because I’d never even met him. I’m looking down the street. There he comes, walking. He wore a black derby hat, from which emerged shocks of curly blond hair, he wore a big old raccoon coat, and he looked like King Gustav of Sweden. That was Saul Kaplan.”

Cahn jumps up and grabs a small chromo-type picture from the wall; seven sober-faced young men in utilitarian-black suits, clutching their symbols of status, their instruments, as they stare at the photographer back in the East Side days of 1930. “There he is—look at him,” he murmurs, pointing to the youthful piano player with her derby hat cocked jauntily to one side. “A dear man,” says Cahn as he replaces the picture.

“I say this to you with deep affection, because I really love Saulie. He has very bad eyes, you know, they kind of spun in his head, and the last time he was in Hollywood, the last time I saw him driving a car, I ran up on the sidewalk with mine!” Cahn guffaws. “I went right off the road in fear! Saulie Chaplin coming at me in an automobile?

“I’d learned a few chords on the piano, maybe just two, so I’d already tried to write a song. Something I called ‘Shake Your Head from Side to Side.’ So a couple of weeks later, on a club date, Saul comes to me and asks me if I’ll listen to something. I sit down while he tapped off a number on the piano. He had made an arrangement of my melody! And may I tell you, I’ve had many thrills in my life, but this has to be one of the top ones. That thrill remains. No matter how many songs I’ve written, the moment the orchestra leader gives the downbeat to the first musical interpretation, it is almost like, you know, spanking the new-born baby!

“These guys, the arrangers—they are the most fantastic people in our world. Go talk to them—they are the heroes of this business. Anyway, when he did this, I said to myself, ‘This man belongs to me.’ Saul was going to NYU, but I am indefatigable when it comes to achieving a goal, even then. I made him quit NYU—he wanted to become an accountant. So I had a great effect on his life, I hope he’ll forgive me.”

A somewhat rhetorical remark, considering that Chaplin has become one of the most successful producers of musical films in the past twenty years, numbering among his credits West Side Story, High Society, The Sound of Music, and the current Man of La Mancha.

“We started to write special material and take it uptown and try to peddle it around Tin Pan Alley. First it was the old De Sylva, Brown and Henderson building, where the Brass Rail restaurant is now; then it moved over to the Brill Building, on Broadway. Did you ever hear stories about that building? One day some famous songwriter had just walked out of Lindy’s restaurant; he got into the elevator and he burped, right after his lunch, and he said to the elevator man, ‘Sorry, something I ate,’ and the elevator man said, ‘More likely something you wrote.’

“And there was another story they told about this songwriter. He always sat in Lindy’s with his facing form, and one day there was some American Legion convention in New York, and he’s sitting there reading his tip sheet, and a guy walks in, a big, burly Legion vet, and he comes up and he says, ‘And where were you in 1917?’ And the songwriter looks up and he says, ‘With Mills Music!’ That’s the kind of thing used to go on around the business.”

Again the phone interrupts. This time one of Sammy’s professional acquaintances is anxious that he come to a party later this week to listen to some neophyte songwriter’s material. “I will be delighted to listen to it provided he plays it for me in Greece,” he counters, and hangs up to return to his saga.

“Oh boy, when I left the Lower East Side to come uptown, that was something,” he remarks. “You know, at that time everything was in New York—the theatre, music, everything. So if a boy lives anywhere in the U.S., he runs to New York, right? But where does a boy who lives in New York already run away to? I went from downtown up to West 46the Street … and I slept on floors. I was determined. Now see, in a Jewish family, when an only son goes wrong, it’s a terrible thing—a tragedy. I mean, if you have four sons, if two go to jail and one goes to the electric chair, well, one guy can still go on to be a lawyer or a doctor. But here I was the only son, with four sisters—and I was going to be a songwriter? Terrible. I was going bad. But I was determined. I could have been home for a nickel subway ride—that should give you an idea how long ago this was—but no. I was going to make it.

“There was a legendary outfit on West 46th Street, Beckman and Pransky; they specialized in booking acts for the Catskill Mountain hotels. They were the MCA, the William Morris of the mountains. I got a room in their offices and we started writing special material. For anybody who’d have us—at whatever price. I wrote for Dolores Reed—she became Bob Hope’s wife. I wrote for Henny Youngman, Hope. And maybe sometimes we’d pick up a few bucks for writing special arrangements for the songs that performers would use in their acts. Funny how things happen. One day a door opens in the building, and out comes a guy named Lou Levy. He stops and does a double-take. ‘Sammy—what are you doing here?’ A childhood friend. In our East Side area he’d been considered a complete bum, a no-good. My father had a little restaurant on Madison Street, and his father had a little vegetable store around the corner. He was the neighborhood bum, and I was a little boy with a violin and not supposed to associate with him. But now we meet again in a building hallway on 46th Street. How about that for fate? Now he’s become a dancer.

“Can I give you an idea how attitudes have changed? He’s earning a living by blacking up his face with burnt cork and dancing with the Jimmy Lunceford orchestra, a black group. He does dances like the Lindy Hop. So we start running around together, scratching for jobs, and one day he tells us Lunceford is going into the Apollo Theatre on 125th Street, the famous Harlem vaudeville house, and Lunceford needs some special material for his orchestra, and I say, ‘Hey, I’m your man,’ and Saul and I quick wrote a number called ‘Rhythm Is Our Business.’ Our second published song. The first one was my immortal ‘Shake Your Head from Side to Side,’ published by some thief up in the Roseland Building, who stole all our royalties with a crooked contract.

“We play the number for Lunceford, and he loves it, and before we know what’s happening, he’s gone and recorded it for Decca Records. In those days, that was a thirty-five-cent label, lower-priced than Victor or Columbia, and getting very big. Lo and behold, the impossible comes true, a publisher named Georgie Joy sends for us, it’s 1935 and we have a published song with a record!”

Even at that early stage of his career Sammy Cahn had definite ideas about the team’s future. “I looked at the sheet-music copy and I saw ‘By Sammy Cahn and Saul Kaplan.’ See—up there on the wall you can still see our original billing. Kaplan—his real name. And I said, ‘Saulie, Cahn and Kaplan is a dress-firm name from Seventh Avenue. You’re going to change your name to Chaplin.’ He said he wasn’t going to. I insisted. He said, ‘Why don’t you change your name?’ I said, ‘I did—from Kahn with a K to Cahn with a C. Now it’s your turn.’ Okay—so we also hired a young girl that Saul had met in the mountains, a girl named Ethel Schwartz. We hired her as a secretary so Saul would stay around the office. He was a boy who liked to go home to Brooklyn. We didn’t have what to eat, but we hired her! Later he married Ethel Schwartz, and they had a baby—her name is Judy, and she is now married to Hal Prince, who has done a few things around Broadway as a producer [The Pajama Game, Cabaret, Fiddler on the Roof, Company, and Follies, to list but a few], and now you have the first act of the Cahn-and-Chaplin story.”

But we do not embark on the second act for a bit, because the phone is ringing again; this time it is the same comic who called earlier. He has been pondering Cahn’s assessment of his performance in The Love Machine, and he is not happy. “I am telling you true,” says Cahn with fervor. “Why should I lie to you? You will come out of this picture smelling like a rose even if it is a bomb. You they cannot hurt. You are not responsible for what they did.” Eventually he hangs up, after several more bursts of sincere ego-massage. “Performers!” he remarks. “They are always so insecure about what they do, and who can blame them? It is such a chancey business they’re in. Where are we?”

At the days when Cahn and Chaplin were succeeding with orchestras.

“We quickly did Lunceford another piece of material called ‘If I Had Rhythm in My Nursery Rhymes,’ which also caught on, and then we were set with special-material-type songs. Very good training. This was the period when the big bands were really catching on in show business. Every Broadway theatre was going into stage presentations with orchestras. The first one that went into the Paramount on Times Square was the Glen Gray Casa Loma Band. Did you know that Glen Gray didn’t conduct it? Some guy stood up with a violin and made like a conductor. Glen Gray played the saxophone. Their first New York appearance, they wanted a way to tell the people that the guy standing there wasn’t Glen Gray. So it was like a forerunner of all the assignments I’ve had ever since, special jobs. Somebody says, ‘Call Sammy Cahn, he writes good for bands,’ because of ‘Rhythm Is Our Business,’ and I get to do the song to introduce Glen Gray. A marvelous guy, by the way.

“Glen Gray had manners, he had morals, he was a great Christian. He would not embarrass that orchestra guy standing in front of the band; he wanted it done subtly. So I wrote a thing that said, ‘Once upon a time there was an aggregation that decided they would become a corporation.’” Cahn is quoting a lyric that is nearly four decades long-gone as if he has just minted the rhymes this morning in 1971. “‘So they decided to have a vote, and they all hit a note, and that was the start of the Casa Loma Corporation. When the brass had to vote, the brass hit a note.’” Sammy enthusiastically recreates the entire act. “And then the brass stands up, and Glen Gray stood up, and they blew to him, and he blew a note back to them, and it slowly became evident to the Paramount audience that that was Glen Gray sitting there, see? ‘Then they handed him a golden diploma … which made him president of the Casa Loma.’ And that was their opening song.”

Very clever and slick, even by today’s more sophisticated standards.

“I like that point,” agrees Cahn. “I think I am slick. It was all those years of working for so many different talents, being in so many situations and having to shape my work to fit them. We got hired to do a show at the old Cotton Club, a night spot. The owner says, ‘We got these beautiful blue costumes, what can you give us?’ So we wrote him a song called ‘Blue Notes’ to go with the costumes.

“Anything! It was a challenge. Like, they had Sister Rosetta Tharpe there, an evangelist singer. We did her a song where she came out on a white mule. A sensation, stopped the show. Of course, the owner got sore at us. Seems the chorus girls were all quitting on him—they found out he was paying that white mule more than he was paying them!

“Then the guy books in Louis Armstrong. My God—the legendary Louis. To me, he was the absolute greatest! I’ll never forget when I first met Louis—it was like the time I met Cole Porter. I’d worshipped his trumpet playing. First thing Louis said to me was, ‘When were you born?’ I told him, he went to a book, opened it, he says, ‘You know who else was born on that day?’ He had this kind of a celebrity autograph book on the days of the year—everybody signed in on the day of his birth. I had to sign. There I am, signing an autograph for Louis Armstrong! … We wrote him a song for the finale, brought out a little kid with a shoeshine box, we called it ‘Shoe Shine Boy,’ and that was a hit, too.”

He suddenly bursts into a chorus of that song, which finishes: “‘Every nickel helps a lot.’” And he stops. “There, that’ll give you an idea how old that is—a nickel for a shoeshine!

“So, anyway, there I am writing for all the bands, and one night Saulie and I and Lou Levy are sitting up at the Apollo, and out comes an act, I think it was called Johnny, Johnny and George. Don’t hold me to it—this is going back thirty years. And they sing a song called ‘Bei Mir Bist Du Schön’ in the original Yiddish. I don’t know if you ever heard that song in its original, but you must believe me, it is funny. They’re singing and dancing it, and I know you won’t believe what I’m about to tell you, but that theatre is literally pulsating. I mean, if you could have a Geiger counter, some kind of a meter, you would find out that the theatre was actually expanding and contracting, just from the beat that song was generating that night. I turned to Lou and I said, ‘Can you imagine what this song would do if they knew what they were saying?’ Because I could understand the words in Yiddish. It’s a boy telling a girl she’s the greatest thing in the world, she’s even greater to him than money—which, believe me, is the greatest tribute a Jewish boy could pay to a girl, you know?

“Tommy Dorsey calls up a day later and says he’s going into the Paramount and he wants a good piece of material. I tell him about this number I’d heard in Harlem, and he thinks I’m crazy. ‘You want me to do a which, believe me, is the greatest tribute a Jewish boy could pay to a girl, you know?

“Tommy Dorsey calls up a day later and says he’s going into the Paramount and he wants a good piece of material. I tell him about this number I’d heard in Harlem, and he thinks I’m crazy. ‘You want me to do a Yiddish number? Me?’ Very stubborn fellow, Tommy. You couldn’t budge him. He actually threw me out of his apartment!

“Couple of nights later I go down to Ratner’s, a dairy restaurant on Fourth Street and Second Avenue. I’m a stubborn guy too. I go into a little music store down there, and I pick up a copy of the original sheet music for this song, and again I go to Dorsey with it. And again he throws me out—with the copy in my hand!”

How did the song eventually end up such a big hit for the Andrews Sisters?

“One day I’m at home. I had a little two-room place on 57th Street, torn down now. The sheet music is on my piano, and in walk the Andrews Sisters, and they look at it and they ask, ‘What’s this—a Greek song?’ I tell them it’s Yiddish, and I play it for them. And again the total contagion of this song manifests itself—anywhere, any time, any place, the room starts to rock, and they start singing it along with me, and they ask, ‘Do you mind if we record this?’ I tell them, ‘Be my guest. What do I care what you do with it? I am totally uninvolved, the middleman, the fellow who’s doing everybody favors.’ Extracurricular work—just like I’ve been doing here”— he winks—“all morning on this telephone.”

Three or four days later the Andrews Sisters, who were well on their way to becoming enormously successful recording artists, were ready to record the song, in its original Yiddish version, in those same Decca studios on West 57th Street where Lunceford was under contract. “And Jack Kapp, who ran Decca, had a monitoring system that let him listen in to each studio. He turns on a button, listens in, and he hears the girls doing the song—in Yiddish. Kapp gives out a yell; what are the Andrews doing, making a race record?”

Cahn gets up and begins pacing his pleasant living room. “I’m going to digress, because this is important, and I don’t care if you quote me or not,” he says soberly. “When I came into this business, there were three separate and distinct branches of American pop music. There was pop standard, in which I operated. The second was hillbilly and Western music. And the third branch was the very bottom of the ladder—race, rhythm, and blues. A race record was any record with a language—Spanish, Yiddish, there were Italian records, Polish, there was ‘Cohen on the Telephone.’ And the very bottom of that rung was blues records. Mostly black singers nobody knew, even the great ones like Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, who sang blues like ‘Go back and get it where you got it last night because you ain’t going to get it here,’ and all that stuff.

“Now there’s ASCAP. The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, formed in 1914, one of the great organizations of the world. A performance-rights society which collects money for its members. Any place in the world that uses music for profit pays ASCAP. Don’t say it’s a monolithic organization—don’t doctors have their AMA?

“Now, the biggest money from music came from the broadcasters. So one day they, the broadcasters, decided they were going to start their own company, Broadcast Music Inc.—BMI. And I maintain that the music we’re listening to today is a direct result of that challenge, and I challenge anybody to deny what I’m saying. All the race, rhythm, and blues, the old bottom of the rung, has become the number-one music in the world today.” Cahn is no longer jocular or even vaguely humorous—he is very much in earnest. “Why? Because when BMI opened up against ASCAP, they obviously couldn’t ask ASCAP to defeat itself by cutting out the pop-standard field, could they? So those BMI guys went to the Western and country music composers. Well! They soon discovered that the fellows in country and Western had more cunning than they’ll ever have, and they went to the next; they went down into race, the black, and now we began to hear a lot of broadcasting of all the stuff that’s so strong today—the old race, rhythm, and blues of the past!”

Cahn waves an accusatory finger. “I’ve read about this. Any analyst will tell you about Jones, who was a disciple of Freud. He too said, what does a child want to hear when he’s growing up? Does he want to go to the opera? Does he want lush music? No—he wants a noisy beat—dung-dung-dung-dunga-dung! And this is exactly what the broadcasters of America fed to the youth of America! All the old blues beats—‘Walk right in, sit right down, baby, let your mind roll on!’ That became number one in America? It sure did. And who did it? Now, who’s to say what effect they’ve had on the manners and the morals of America? And go right ahead and quote me!”

Shaking his head angrily, he subsides on the couch.

“Okay, end of digression. Back to ‘Bei Mir.’ Kapp insists on a set of English words to the song before they can record it. Remember, this is 1939, ages ago. So Lou Levy leaves the copy up at my place, he wants a translation. One night I take a red pencil and under each Yiddish word I write a lyric. Now, when I write a lyric, I always start at the top. I never ever know where it is going. Jimmy Van Heusen told me later that his earlier partner, Johnny Burke,1 always started at the bottom. He’d lay out a key idea, and then he’d write from the line backwards.

“You see, songwriting for me is a great, great adventure. I have so much fun. I’ve learned that if I start at the top, i will go where I need to go. It will always be there if I just stay with it. And the minute I got ‘Bei Mir Bist Du Schön, please let me explain,’ that was the key to the whole song.

“I get the song finished, and here’s where the drama starts. What have we done? We’ve taken another man’s song and changed it, without asking permission or anything! And now, all of a sudden, it occurs to us we’ve done this, and somebody says, ‘Hey! Now, how are we going to do this?’ I look at the sheet music, it says, ‘Words by Jacob Jacobs and Music by Sholom Secunda. Published by J. & J. Kamen, Roebling Street, Brooklyn, N. Y.’ I had to go out to Brooklyn and find them. Now, I am not making this up to give you an anecdote. Two little men, about five feet tall, black derbies, the two of them in a little store—light blue serge suits, like Tweedledum and Tweedledee from Tel Aviv! Specialized in publishing songs from Yiddish shows. See, Yiddish composers would publish their own songs and then stand in front of the theatre when the show was playing and sell the songs to the audience afterwards. The show runs, then it closes, the songwriters are finished, they’d bring in the songs to J. & J. Kamen and sell everything for $100 or so. One of those songs was ‘Bei Mir Bist Du Schön.’ They’d bought it for maybe $30. That was the way it worked then. I had to explain to those two little Kamen brothers that I’d written a lyric to their song! To Jacobs’ and Secunda’s song. And that it was recorded already, and how could I explain to them that the thing had taken off, it’s already a big hit, everybody’s playing it, even Guy Lombardo is using it at the Roosevelt Grill? You can’t believe what a hassle there was about royalties. By the time it’s straightened out—the Kamens getting theirs, the writers getting theirs, the Warner Brothers publishing house where we’re under contract getting theirs—finally, Chaplin and I, the ones who made this international hit, we get between us, for the lyric and the setting, one and a half cents a copy! Oh, I tell you, they negotiated that one out for months.”

By now the Cahn-and-Chaplin team had found steady employment writing for films. Not the opulent Hollywood-type musicals, however; they had found a rather unique niche writing music and lyrics for two-reel shorts, out at the old Vitagraph studio in Brooklyn. “We’d signed a contract with the Warner music publishers. Herman Starr ran it, and he sent us out to Brooklyn. They cranked out shorts as if it were a sausage factory; the motor of that place was, ‘We don’t want it good—we want it by Thursday!’ Vaudeville acts used to come out and work one, two days and make a short. We turned out instant material. Do you realize that we’re the first team of songwriters that ever wrote a hit for a two-reel comedy? A song we called ‘Please Be Kind.’”

Another phone call; it is Cahn’s travel agent checking on his reservations for Greece and other points. And then someone calls long-distance from California: can Sammy do some special material for a commemorative dinner? (“Baby, I would love to oblige you, but it’s not only my body that’s going to Greece, my head is also booked for the flight.”)

“Where was I?” he queries.

The eventual move to California?

“Oh, yes. So now we’ve had this pretty good run of success, and Herman Starr, who’s given us a lot of impetus, now pulls a brake on us in a kind of silly way. Because we were under contract, he never published anything of ours. A very naïve attitude. He’d say to us, ‘Look, if Harry Kabibble walked in with a song, I better publish his song. Your songs I got.’ Well, we went into a real rut. So Saul and I walked in and said, ‘Send us to Hollywood. We’re not doing anything around here; out there something could happen.’

“Starr bought that idea, we went to Hollywood, and Starr sent along some kind of note to the bosses at Warner’s saying, ‘Here are two songwriters, they get paid by us in the East—please use them, you got them for nothing.’ And you know what people do with something they get for nothing? That’s what they did with us. For two years. We hung around, but the only time we even got on the Warner lot itself was when I walked on with my old pal Jimmy Lunceford when he was there to make the picture Blues in the Night!”

SO how did Cahn and Chaplin survive? “It got better,” says Cahn. “It couldn’t have been worse. Eventually I got to work for all of them—Warner, Harry Cohn, Paramount. I could tell you plenty of stories about that, but I won’t, because I am now off to Greece.”

He vanishes into the bedroom to dress and finish packing.

To call a halt at this point in his reminiscences is somewhat akin to enjoying their hors d’oeuvres at a gourmet restaurant and then having the chef close down the kitchen.

He emerges from the bedroom in slacks and a double-breasted blazer, very much the elegant world traveler and bon vivant. “It’s not only you I’m leaving!” he soothes. “What about all those people who keep calling me and I won’t be here to answer? Say, maybe you could stay here while I’m gone and answer the phone! Ask all my friends who call to carry on with my story until I get back!”

He bolts his door and walks down the hallway with his bags, headed for Greece. From behind, there comes the faint, unmistakable sound of his telephone, ringing inside the closed apartment. Sammy Cahn’s friends are already missing him.

Sammy Cahn Revisited

Almost eleven months have passed since the peripatetic Mr. Cahn departed for Greece. In the interim he has been to Venezuela, several times to California, and back to Europe, thus pleasing some international airlines. Miraculously, he materializes striding down a rainy London Street and halts, crying, “Hey! We never finished! I did a two-hour lecture up at the YMHA on 92nd Street—told them all about my career. Got great notices.”

Shall we continue now? No, he is off to New York in the morning.

Eventually, through a minor triumph of logistics and split-second timing, we do continue, back in New York. But now the scene has changed; Mr. Cahn is working in the opulent offices of a large cosmetic company.

The two floors the firm occupies in a huge New York tower are decorated in the avantest-garde. A lovely receptionist sits at a lavender desk, where she and it seem to float in mid-air, sans visible means of support. There are mobiles hanging everywhere. Halls are lined in soft gray furry plaster, with vivid neon tubing for illumination. Individual offices are decorated with the latest in Italian mod furniture, walls are hung with an array of wild abstracts and neo-realistic pictures; one might well be in an art gallery. Crouched over a functional electric typewriter in one of the offices is a found object, Mr. Cahn. He wears a casual sport shirt and slacks. Has he perhaps gone into the cosmetic business? Peripherally. He is working on a set of special-material lyrics which he himself will perform tomorrow afternoon at the company sales meeting in Miami. Eight solid pages of parodies to be sung to the tunes of his famous songs.

“I do this only for my friends,” he says, “and I write gratis. If I were doing it for an actor to use in his act, the price would stagger you. Joey Bishop asked me would I do a take-off on Fiddler on the Roof for Vegas this spring. I write him a thing called ‘Gambler on the Roof’ and it is the biggest hit that ever happened there. Joey is thrilled and he keeps asking me what he owes me, and I say, ‘Hey, I don’t make my living writing special material’—although that’s how I started off, remember—‘I make a living writing songs.’ If he sends me a nice gift or something, okay, but if he doesn’t, I still enjoyed it. It was a kick! Excuse me, I have a line to fix here.”

A smashing young secretary appears, and Cahn hands her revised lyrics for reproduction. There is discussion about his flight to Miami the following morning in the company’s private jet; he will travel with the president, who is a good friend. “I’m doing this as a favor to him,” he says, “but I really enjoy getting up and performing so much I should pay. I take all my songs and revise them for the occasion. I get up and say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, in ancient times the lyric-writer was the news media. For instance, the word “lyric” comes from the Greek word “lyre”—a man with a lyric would go from town to town singing the news. If he sang about Danny Deever getting hung in the morning, that was something that was really happening. So tonight I will go back to being the news media and tell you the story of this occasion here—with the melodies of my songs, and new lyrics.’ And slowly, as I do one song after the other, it has an amazing effect on the audience. You can hear them whispering, ‘Hey, he wrote this song … and did he really write that?’”

More interruptions—the usual fusillade of phone calls from friends and business cronies, the movers who are arranging to transport him shortly to a new East Side apartment—and eventually he returns to the subject of his songwriting. “Now. Where were we?”

Before he left for Greece long months ago, he had talked about his early partnership with Saul Chaplin, which had brought them to Hollywood in the mid-’30s. Now, what about his subsequent collaboration with Jule Styne? “Hey, did I tell you about how we wrote ‘Three Coins in the Fountain’?” he demands. “Because one night I was at a party where Jule Styne and Frank Sinatra were reminiscing about it, and as I listened, I was amazed to hear how they remembered it. I remember it the way it happened.

“Jule and I had a great run of hits in Hollywood during the war, as you know, and then after High Button Shoes, which we did on Broadway, he stayed in New York—he loved the theatre. I came back to the Coast. Now it’s ten years later and the phone rings. I’d been working with lots of people, but it’s Sol Siegel saying Fox is going to make the first Cinemascope musical Pink Tights, with Frank Sinatra and Marilyn Monroe, a huge project, and Frank wants me to do it with Jule. That’s why I’ll always be eternally grateful to Frank, believe me. Do I want to do it? More than anything else in the world. So Jule comes out, and we’re reunited, and we proceed to write what I believe is the best score Jule and I have ever written. Why do I say that? Not arrogance,” he says. “It’s the best score because it has not been heard. And, for all I know, it may contain ten hits, because anything that’s unpublished is a hit. When it’s published, it becomes either a hit or a flop. But till it’s published, it’s a hit, right?” He beams across the bright red plastic desk.

“So our score was never heard. Why not? Because the day we are supposed to go in to record it, Marilyn Monroe, our female star, runs away to Japan with Joe DiMaggio! That’s on public record. Leaving everyone at the studio high and dry, and there we are, a score, cast, everything ready, no female star! Now we’re just roaming around, not knowing where we were going or what to do, when Mr. Sol Siegel walked into our office. It’s about 1:30, after lunch, and he said, quote, ‘Could you fellows write a song called “Three Coins in the Fountain”?’ unquote. I said, ‘We could write you a song called “Ech!”’ He said, ‘I don’t want a song called “Ech,” I want a song called “Three Coins in the Fountain.”’ I said, ‘What for?’ He said, ‘We just finished a picture in Italy. The New York office wants to call it We Believe in Love. Zanuck and I hate the title, but they’re adamant—and we feel that if we can get ’em a song called “Three Coins in the Fountain,” it may dissuade them.’ I said, ‘Okay, can we see the picture?’ He said, ‘You can’t see the picture, the picture’s all over the lot, they’re scoring, they’re dubbing, they’re doing all sorts of technical things to the picture.’ I said, ‘Well, can I read a script?’ He said, ‘What—read the script? We need the song right away!’ I said, ‘Hey, what’s this picture about?’ He said, ‘What’s it about? Three girls go to Rome hoping to find love and they throw coins in a fountain.’ I said, ‘That’s fair enough.’

“Now, you ask which comes first, the words or the music?” asks Cahn. He grins. “I’ll tell you which—the money! Or the phone call—or the request! Which we have. I go to the typewriter and I sit down with a piece of yellow paper which is my work sheet. I look at it about tow, three minutes, and I start to type. The title. ‘Three coins in the fountain, Each one seeking happiness, Thrown by three hopeful lovers. Which one will the fountain bless?’ That took me two or three minutes to type. Now, as simple as it sounds, it is the result of twenty years of lyric training. And my fingers hit a cadence that comes from the title … da da da-da da-da, and so on. So that’s already laid in for Jule. I hand this piece of paper to Mr. Styne, who looks at it. Now, I will tell you that it would take a computer the size of a universe to estimate how many different combinations of notes are available to those words. But in about half an hour, with Mr. Styne’s talent working, we start to hear the first eight bars, like so.” Mr. Cahn proceeds to sing the, in a soft, true voice, with a professional attack.

“And we agree that this is lush, Latin, and correct. Now, if he did not come up with something that was acceptable soon, I would have changed the lyric around, made another kind of combination. But the melody was right, and now, having agreed to that, the melody is three-quarters finished. You see, in a song, melodically, we go A—A—B—which is the bridge—and then back to A. And we’ve got our A. He hands me back the paper, and I look at it, and I say, ‘Jule, I don’t know what else to say. I’ve said everything that is pertinent to this song.’ And Jule says, ‘How about mentioning Rome?’ I say, ‘That’s fair.’ I put the paper in, I write, ‘Three hearts in the fountain, Each one longing for its home. There they lie in the fountain, Somewhere in the heart of Rome.’

“Not bad. Swift. Easy. So I say, ‘Jule, I now can guarantee you this song is finished.’ And we got into a kind of dialogue, because once before we wrote a song together called ‘I Fall in Love Too Easily.’ I had written a sixteen-bar lyric [the customary form for years was thirty-two bars], but I wouldn’t add another word in it; I said, ‘That’s all the song has to say!’” Again from memory, he sings the lyric of the lovely Sinatra ballad which he and Styne wrote for the young singer’s repertoire many years back.

“But Jule says, ‘Hey, you’re not going to do one of those. We need a bridge. Give me a bridge!’ So I look at the paper, I stared, and I finally typed, ‘Which one will the fountain bless? Which one will the fountain bless?’ I hand it to him. He reads it aloud and asks, ‘Don’t you want to rhyme it?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t want to rhyme it. That’s what I want to say.’ He says, ‘You know, you used this line already.’ I said, ‘I don’t care.’ That is what I wanted to say. And it’s getting a little edgy between us, you know? So he goes back to the piano and he’s angry, and he starts to play, very flat and monotone, dum dum dum da dum da dum! Jule looks at me. I said, ‘That stinks.’ He says, ‘You’re telling me it stinks? Of course it stinks!’ I said, ‘What about trying to help it? Don’t do exactly what I did.’ And that’s what Jule did.” Cahn sings the melody with great feeling and emphasis. “I listened, and I said, ‘Ah, isn’t that great?’ Jule goes to write it down, and he says, ‘Just a moment. This bridge is only four bars.’ Now, all bridges are eight bars. Eight bars, eight bars, bridge, closing, eight bars. Thirty-two bars. Why the hell was this only four bars? Now I’m floundering, because in those days songs had to be thirty-two bars. Not today. SO I go back to the top of the song and I run it through, and I add, ‘Three coins in the fountain, Through the ripples how they shine. Just one wish will be granted. One heart will wear a valentine. Make it mine, make it mine, make it mine!’ He said, ‘You son of a bitch, we picked up the last four bars in the tag—we’ve got thirty-two bars!’ I said, ‘And you were worried?’

“It is three o’clock. The door opens and in walks Sol Siegel. He asks how we’re doing. I tell him we’ve finished, but if he’ll give us an hour we’ll do it for him. He said, ‘What do you mean, give you an hour?’ I said, ‘We have to learn it—we have to woodshed, we have t find what’s the best key, we have to find what’s the best accompaniment for it, we have to find the best way of doing it for you.’ And he said, ‘Are you guys crazy? Why do you have to learn it? You wrote it!’ We simply could not make the guy understand performance.

“Understand, performance, that’s the most important thing about doing a song for somebody the first time. I mean, if I walk into a room to do a song for you, I’m the most expensive singer in the world. I walk in without an orchestra, no makeup, no lights, I don’t sing any song you ever heard before. It’s just a little guy with a mustache and glasses. If you like what I sing, you owe me a lot of money. So we really work up to that—it’s moment-of-truth time. But he was so anxious and insistent, I looked at Jule, he looked at me, and he said, ‘Let’s all hear it for the first time.’ He played me an intro and I started to sing the song. I finish, and he said, ‘It’s marvelous—marvelous!’ I looked at Jule—that moment is better than a kick in the head, you know? Beautiful!

“Siegel said, ‘Let’s do it for Zanuck!’ We’re all running down the hallway to Zanuck’s office. He says, ‘The boys have a song!’ We played it again, I sang, ‘Make it mine, make it mine, make it mine!’ Zanuck says ‘Sensational! Listen, we have to have a record right away to send to New York. Would you make a record—for demonstration?’ I said, ‘Me? You’ve got to see me to believe me—you can’t put me on a record.’ He asks, ‘Who can we get?’ I said, ‘Well, Sinatra’s walking around here getting a quarter of a million for not making a picture. Why don’t we get him to do it?’ He said, ‘Would you ask him?’

“I go find Sinatra. I say, ‘Frank, we’ve just written a song for Sol Siegel called “Three Coins in the Fountain” and he wants me to make the demo.’ He says, ‘You?’ He snickers. I said, ‘You’re right. Would you do a little demo record?’ I caught him in a good mood. ‘Sure, when?’ I tell him if he’ll come around tomorrow at two, Jule will teach him the song, not too tough, and we’ll go and do it. Fine. I immediately leave Sinatra and go find Lionel Newman of the music department. I ask him is he going to have any musicians in here tomorrow. He says, ‘Am I going to have musicians? It happens I’m going to have sixty men. We’re scoring Captain from Castile!’ I said, ‘We’ve got Sinatra, we’ll whip up a little orchestration, he’s going to do this new song, okay?’ Fine. I give him the lead sheet.

“Next day at two, Sinatra comes by. We teach him the song. And now we stroll over to the recording stage. We open the door, and there are sitting sixty musicians. And Sinatra says, ‘What the fuck is this?’ I said, ‘Oh, they happen to be here.’ He gives me the jaundiced eye and says, ‘They happen to have an orchestration in my key?’ I say, ‘They happen to have an orchestration in your key.’ He gave me the eye again. I said, ‘However, if you would rather do it with Styne at the piano, I can have them all take five.’ He says, ‘Take five? It’ll take them half an hour to get out of here! Let’s hear the orchestration!’

“Again, that has to be the best moment for the composer and the lyric-writer … when the music is heard for the first time. Lionel Newman stood up, brought them to attention, pointed to the strings, who started to play a lush intro, and then the harpist, who began to make waterfall sounds with the harp. And then Sinatra made the record.

“And I swear to you, we were standing at the back, enjoying it, and one of the Skouras brothers—it was probably Spyros, who was the boss man at Fox—said to me, ‘Let me understand you.’ He then asked me one of the most naïve questions in the world. ‘Sinatra’s going to record this song, a record will be made of it, it will be number one? Is that correct?’ I said, ‘That is correct.’ Anybody who asks that naïve a question deserves that naïve an answer.

“But what really makes this the most fantastic story of all is that this song does go on to be number one in the world. It won the Academy Award for Jule and me. The record Sinatra made that day was used as title music for the picture, which was a giant hit. And during all this excitement, which took place in twenty-four hours, give or take an hour, everybody forgot one vital and important element.” Cahn pauses with the proper dramatic effect and smiles. “Nobody made a deal with us for that song!

“People ask me what is the most I ever made on a song. Well, the most has to be ‘Coins’—because long after it became a giant hit, Sol Siegel came into our office and he was very depressed. He says, ‘I’ve just heard from the front office about a small detail—you’ve never signed a contract for the song.’ ‘Hey, that’s right!’ I said. ‘The song is ours!’ Do you know what it means to own that song a hundred percent? Incredible. He says, ‘It can’t be your song, Sam.’ I said, ‘Don’t tell me it can’t be mine. It can be mine, but it can’t be yours. Let’s assume that this song, for which we didn’t get paid— let’s say it went on to be a flop, nothing. We did the work, we did everything for nothing, nobody would have come by and said, “Hey, we owe you money.” The roll of the dice came up seven, and it’s our roll.’ He said, ‘Sammy, everything you said is correct, but we cannot perform this song in our picture, because we—Fox—don’t have a deal on it.’ Which is correct. They are in dire trouble.

“Well, eventually we made a deal. Fifty-percent split on the copyright, but the entire royalties remained ours. And that is the incredible story of ‘Three Coins.’”

The secretary has reappeared with a shopping bag full of assorted packages—stockings for Mrs. Cahn, several flacons of the firm’s best perfumes, and Xerox copies of the lyrics for tomorrow’s performance in Miami. Cahn prepares to leave, and as the secretary departs, he croons “I adore you!” at her (a fragment of one of his many love lyrics). The lady is obviously delighted.

“But I’ve always had lucky experiences with composers like that,” says Cahn. “With Saul Chaplin, the words and music always seemed to come almost simultaneously. I’d start, ‘This is my first affair,’ and he’d be playing a tune an give me back, ‘So please be kind.’ And with Jule, he’d play you a melody. Something like, ‘Time after time,’ and I’d pick it up: ‘I tell myself that I’m so lucky to be loving you.’

“Work fast. A whole melody. With Jimmy Van Heusen, the words come almost simultaneously. We got a script from Paramount, Papa’s Delicate Condition, and I read it and the most pertinent word in the script is the word ‘irresponsible.’ Do you have to be a genius to come up with the title ‘Call Me Irresponsible’? But then, Jimmy and I sat for hours and hours trying to figure out how to write a song that would denote the walk of a fellow who’s just ever so slightly drunk—that was Jackie Gleason’s character. And then we finally come up with the exact phrase.” He leaps to his feet and does a slight rolling walk up and down the elegant little office. “What do you say when a drunk is walking like this? Yes, sure—that’s walking happy, right? Which is how we got that one. We wrote a song about all the walks people can walk. Gleason sang it to his daughter. ‘Walking Happy.’ Later we used that as the title of a show in New York.

“Another time we’re writing a picture for Sinatra called A Hole in the Head, and I’m walking around and I come up with the idea, ‘High hopes— high apple-pie-in-the-sky hopes … ‘ ESP. Next day Van Heusen says, ‘I was with Sinatra last night.’ He was in charge of Sinatra from eight to five in the morning. See, I hung around Frank in the afternoon; Van Heusen was the night shift! He said, ‘Frank thinks we ought to have a song for the young boy, the kid in the picture who plays his son.’ ‘Hey,’ I said, ‘I have this title, “High Hopes.’” It sounds good. So he says, ‘Let me come up with a tune.’ He comes back with one of those two-four tunes—very martial. ‘When you’re down and out, lift up your head and shout, you’re going to have some high hopes!’ I didn’t like it, and he knew right away it wasn’t good, so he said, ‘Let me try again,’ and he came back the next day, and he had a spiritual. ‘Sing Hallelujah, Hallelujah, and you’re bound to have some high hopes!’ I didn’t like that either, but I never tell a composer I don’t like his melody. ‘Cause that’s a thing that anyone who deals with creativity knows—you never say, ‘I don’t like that.’ There’s a gentler, kinder, more graceful way.

“May I tell you that the best student of creativity, as far as I’m concerned, was—and is—Mr. Sam Goldwyn. Jule Styne and I wrote him a great song once. The Kid from Brooklyn was the picture. Goldwyn said, ‘That is great. Great.’ And our hearts leaped, and then he said, ‘But I just feel—I just feel you guys can do better.’ He said, ‘Look, you see this song here—we have it right here now, nothing can destroy this song. Here it is, I love it. Great. If you cannot do better, we have this, but I know in my heart…. ‘ So we went away and we wrote another song, and Goldwyn said, ‘That is infinitely better. Tell the truth, isn’t it?’ And we said, ‘Yeah—it’s better!’ He said, ‘But you know something? I feel here, here in my heart, you can do better than that.’ Three times he did that to us! With the fourth song, I said, ‘This is the best we can do!’ He said, ‘That’s what I want!’

“So I never say to anybody, ‘I don’t like it.’ I say, ‘Look, we have this, let’s try for something else.’ I said, ‘Jimmy, we’re writing this song from the wrong angle.’ I was taking the blame. I said, ‘Instead of writing this song from the angle of human beings, why don’t we try it from the angle of animals?’ And the minute I said it, I wanted to tear out my tongue, because I was telling the man who had written the single greatest animal song ever written!” (“Swinging on a Star,” the great Bing Crosby hit, contains references to mules with long funny ears, and so forth.)

“But I know how to think on my feet. I said, ‘Forget that—not animals.’ I’m looking on the bungalow floor at Fox, where we’re working; it’s in the country-club area of L.A., and there are some ants. Ants running around. ‘Insects!’ I said. ‘What do you mean, insects?’ he asked. I said, ‘Well, you just take an ant. An ant has a sense of fulfillment when it moves from one place to another.’ Jimmy looked at me and he said, ‘Yeah?’ ‘The minute you say that it writes itself; I just happen to be privileged to be there. ‘Just what makes the little old ant think he’ll move a rubber tree plant?’ I know ants can’t move rubber trees, but it has to be a rubber-tree plant, that’s what makes the cadence and the syllables fall properly—and the song is home and free, and you just happen to be lucky to be there getting it written.

“Later we were asked to come out to Peter Lawford’s house to meet the Kennedys. They all wanted to know did we have a song that would work for his political campaign, so I suggested ‘High Hopes.’ They asked if we could make a campaign song out of it, and I said, ‘The question is not can I make a campaign song—the question is, do you want it? ‘Cause if you want it to be, that’s what comes first. Remember—not the words and music, the request. Right?’ And they said, ‘Try.’

“That night, going home, Van Heusen says, ‘All right, big mouth, how’re you going to make a campaign song out of that?’ And I do not know. So we’re sitting down, examining, examining. Getting absolutely nowhere. Do you know what? You cannot rhyme Kennedy. Try it. I defy you.”

Cahn pauses, with a fine sense of drama.

“So, after hours of frustration I think of something—a trick that goes back to my old days of writing special material. I said to Jimmy, ‘Why don’t we spell it?’ And it became, ‘K-E-double-N-E-D-Y, Jack’s nation’s favorite guy, Everyone wants to back Jack, Jack is on the right track, and he’s got high hopes.’ The campaign song for 1960….” Cahn beams. “That, for me, is great adventure!”

He grabs all his assorted belongings. “Come on, let’s get going. I have thirty-seven things to do before I go to Miami tomorrow.”

Our mini-safari hurries down the long gray hall with its vivid neon tubing as Cahn waves Auf wiedersehen to assorted young secretaries.

“But we’re nowhere near finished,” he insists. “I haven’t told you about when Jule and I wrote ‘It’s Magic,’ and Miss Doris Day’s first screen test at Warner’s.” The elevator is dropping us to street level, and then Cahn is striding purposefully eastward on the crowded sidewalk. “Follow me!” he commands jovially. Tomorrow he will be wowing the assembled salesmen down in Miami, but he will be back in New York within hours after that. There are far too many people who need some of Sammy Cahn’s time— and all of Sammy Cahn’s talent.

“Going to tell you a secret,” he announces. “I’m going tow rite a book about all the things that have happened to me. Got the title. It’s going to be called ‘Did He Write That?’ Like it?”

Fine, but isn’t he perturbed that some of it has already been bestowed on other authors, including this one?

“Hell, no!” he chortles. “I’ve just been auditioning it for you!”

And off he goes, walking happy.