ON JUNE 17, 1972, Fiddler on the Roof became the longest-running musical show ever to play on Broadway—thus outlasting such previous classics as Oklahoma!, South Pacific, My Fair Lady, and Hello, Dolly! There is a wide-screen version of Fiddler playing all over the world. Even if it didn’t exist, there are so many international productions of the musical saga of Tevye, the milkman, and his friends of the tiny Russian-Jewish village, that the show’s long and happy future life is as close to guaranteed as you will ever get in show business.

The superb score for the Jerome Robbins production was written by Jerry Bock; the brilliant lyrics, which seem to be such a generic part of Joe Stein’s adaptation of Sholom Aleichem’s stories, are the work of Sheldon Harnick.

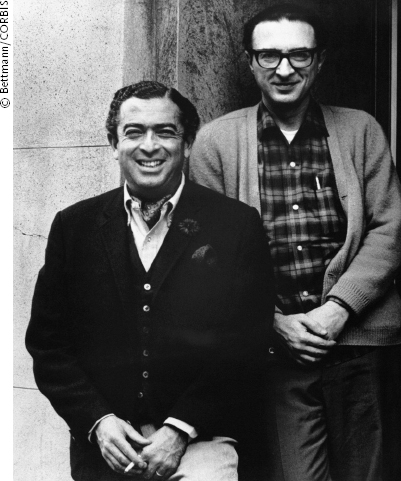

Both men are in their mid-forties. Even now, years after Fiddler’s opening night, they regard the phenomenon of their work’s huge acceptance with audiences everywhere with a certain amount of justifiable perplexity, “I still don’t believe it,” says Bock. “Sometimes I often doubt if it’s all true.”

He is an outspoken man, articulate and witty.

Harnick, who began his career as the writer of comedy songs, views the world (and the word) through his spectacles with much less optimism than does Bock. “Temperamentally,” says Harnick, “We’ve always been exactly the opposite. Jerry has been the world’s greatest optimist, and I’ve always been rather pessimistic. That’s one of the things that has made us such a nicely meshing creative team. Between us, we help bring the other either down to earth, or up to earth.

“You really can’t believe a thing like Fiddler and its success is going to happen when you start,” says Bock. “Maybe if you’re Rose Kennedy, and you nourish the ambition to have your son become President, and you move your entire life so that happens, fine. But for us, Fiddler was only another show—The next show. It was never designed to be a blockbuster.

“We started it down in a cellar in New Rochelle, all by ourselves,” he recounts. “We’re not always asked, you know. But if you’re not asked to take on a project, then you have to take the bull by the horns and do it. If you wait for the phone to ring, then you start building a wall of self-defenses—one that eventually, you never can see over….”

“Somebody sent me one of the few novels that Sholom Aleichem had written, Wandering Star. Very wandering and diffuse it was, but I suddenly discovered in it a whole world! Remarkable. Then Joe Stein touted us onto Aleichem’s short stories, ‘Tevye’s Daughters,’ and ‘The Old Country.’ We ate them up! They struck such a responsive chord in both Shel and me. I’d never lived that life—I come from the Mid-West, and so does he—but as a child I’d had some of it passed down to me by my grandparents. So Shel and I decided to take off on this and write, even before we had a producer.”

The early history of Fiddler and its creation is replete with turn-downs and negative reactions. “We were urged not to continue because it was so special,” says Bock, “Some people were embarrassed to hear its open Yiddish flavor. Oh, sure, there had been shows like this years before, down on Second Avenue, in the purely Yiddish theatre, but this was the nid-’60s now, and the notion of doing such a parochially Jewish show for a catholic audience—in this case, Jewish,” he grins, “struck people as very odd. They were sure that we’d run out of audiences for the show very quickly.” He shakes his head with wonder. “And now it’s more than eight years later. Of course, we caught a larger-than-Jewish audience very early on. We won the National Catholic Award, and audiences responded very deeply wherever it played. All over the world, even Finland—I don’t think there are more than 200 Jewish families in Helsinki! So there obviously must be something else in the show that captures them. It certainly can’t be simply the Jewishness, so-called, of Tevye’s story.”

Eight years, hundreds of thousands of LP recordings, and stacks of fat royalty checks later, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick are quite matter-of-fact about their success. Humble they are not, but neither are they arrogant. Both men are far too clear-eyed about the long and hard travail that brought them to this plateau of accomplishment. To have “made it” on the postwar Broadway scene of the ’50s and ’60s was a far more difficult and frustrating task than it might have been back in the lush days of the Coolidge administration, when musicals were not a luxury item with $12 tickets, but a staple item for the tired businessman.

Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick

Their partnership began in 1957, when the two teamed up to write the score for a musical called The Body Beautiful. The show opened on Broadway a year later, and lasted for only two short months. An inauspicious start, to be sure, but not their first professional experience. Both had been struggling separately for a long time.

Jerry Bock had never planned to compose music. “There was a piano in our house, music was always available, but I never took it seriously.” He went to the University of Wisconsin intending to major in journalism. “But on an impulse one day I went into the Music School and auditioned a thing I’d written in high school. Bugle calls in the styles of various classical composers. I shudder to think of my own arrogance—it must have been terribly embarrassing for them. They said, ‘Mr. Bock, you show signs of inventiveness. Are you willing to start from scratch, as a beginning music student?’ I could have said no; but there it was, that moment of decision. Strictly on impulse, I said yes—when I’d had absolutely n intention before of doing it!”

Along with a fellow student, Larry Holofcener, Bock began to write songs. “After graduation, it was ‘New York, here we come!’ Ordinarily, we would have had our eyes blackened—but remarkably enough, there’s a happy ending.”

A family friend had secured the two young men an introduction to producer Max Liebman, who was at the time putting on a live weekly television revue, “Your Show of Shows,” starring Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca. “He listened to our samples—four kakamamie songs—and hired us that day. Very lucky. For the next few years we worked very hard. Numbers for the chorus, and the ballet group, and for production numbers—everything! Three days to write, three days to stage. Seventh day, the show went out on the air—an hour—live. No such thing as videotape in those days; it was a new show every week!

“Later on, I found out that sort of pressure-writing was an invaluable experience for me. You go out on the road with a new show and suddenly you’re faced with rewriting and replacing. I had all that accumulated experience to draw on—writing against a tight time deadline, murder, but exciting.”

Bock also served an apprenticeship at a summer resort called Tamiment, in the Catskill mountains. For three summer seasons there, he and his partner wrote the equivalent of a one-act musical revue each week. “It added up to an average of two, three or four songs a week for ten weeks,” he says. “Marvelous training—we got direct contact with audiences.” In 1955, some of Bock’s songs were in a revue called Catch a Star on Broadway, and he continued supplying material for Max Liebman’s weekly “Your Show of Shows.” Eventually, in 1956, there came a chance to do a Broadway show, an original score for Mr. Wonderful, which starred Sammy Davis, Jr.

Set down in order, it all seems to have happened with a steady forward thrust, but Bock today has vivid recollections of the “down” periods. Far too many of his contemporaries from the ’50s have long since given up theatrical writing; he is very much aware of the rate of attrition among the talented people he knew. “From all over the country they arrive in New York, hoping to make good in show business, but most often they’ve ended up in advertising agencies, writing commercials, or writing arrangements for pop groups; anything where there’s a living to be earned.” Bock considers himself lucky to have been able to stay on the theatrical scene. “There were years when I didn’t think I could stick it. Flop shows. Harnick and I worked nearly two years on The Body Beautiful—it closed in two months. Later, we had other flops, but I just felt I had to keep on going. My wife and family have always been remarkably helpful and encouraging. I’m sure they’d all have preferred me to go into some more pragmatic business!”

Sheldon Harnick’s years before he met Jerry Bock were also replete with adverses. His origins as a neophyte lyricist were rooted in the comic muse. “Little verse, doggerel, nonsense poetry,” he says today. “Maybe it was my way of getting attention when I was in high school. I’d come under the influence of Benchley, S. J. Perelman, Thurber, Frank Sullivan. They were a constant inspiration, if that’s the word, to try and write with wit, the way they did.”

When the war came (“World War II,” he grins, “and doesn’t that say volumes to you about our age?”), Harnick was drafted into the Army and stationed in Georgia. There he began to do his first real writing, lyrics and sketches for soldier shows. But he was also an accomplished violin player; writing was still merely an avocation.

When the war ended, Harnick returned to college. When did the switch from music to lyrics take place?

“I was playing with a dance band,” he says. “Seventeen pieces … Henry Brandon’s orchestra at the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. Very good job. But business got worse and worse, the band got smaller and smaller. We’d broadcast five nights a week at midnight; they’d hang that mike above me and I’d have to play. Nights we played on a nation-wide hook-up, and I’d get all tied up in knots. Years afterwards, an analyst helped me to find out that I was a repressed hysteric; I didn’t realize that about myself….

“We laid off a couple of weeks—and when I picked up the violin again, I couldn’t move my fingers. Couldn’t play at all! Terrified me. I went to the doctor and he diagnosed it, gave it a name which maybe he’d made up, or maybe he hadn’t. He said he’d had a similar case in Vienna, and he called it Geigerkrampf—fiddle-cramp. Agonizing. Even though I began to come out of it, I began to realize that I couldn’t make my living at this any more, so I took my savings and came to New York.”

“Remarkable, when I think back on it,” Harnick comments. “Years afterwards, when I’d been analyzed, my analyst said to me that I obviously possessed the quality of drive—but that in me, it expressed itself in stubbornness. I’d come to New York with two major escape routes. If I couldn’t make it as a lyricist, I could either be a librarian—that I knew I could do; the other thing I thought I could do was to be a guide at the United Nations.

“I just hung on. I found out that the UN only used young ladies, so that was out, and I kept on writing. How easy I was on myself,” he chuckles. “I set myself the schedule of writing one song a week! … I got a few little things into collected revues, and people used some of my songs in night club acts, but nothing really major happened.”

Among the “little things” that Harnick placed was a satiric number with which Alice Ghostley regularly stopped the show in New Faces of 1952, the rollicking “Boston Beguine.” Harnick’s friends Charlotte Rae and Arte Johnson were performing his material with great success, but usually to highly limited audiences.

“Things were very lean,” he says now. I remember once a television producer, Norman Lear, came to New York to persuade me to come West and work on a new show of his out there. I was thrilled at the chance, and I desperately needed the job. But it ended up being the craziest meeting. He had one or two drinks at breakfast, and then he started saying, ‘Sheldon, I’m not going to ruin your life! You have no idea what a rat-race the business I’m in is. I’m not going to spoil things for you. If you stay here in New York you’ll end up doing something wonderful!’—and I kept saying to him, ‘Please—corrupt me.’”

Harnick managed to find some employment that served his talents and his lean bank account during this period of struggle, at a summer resort called Green Mansions (very much akin to Tamiment, Green Mansions was also the training-ground of lyricist Lee Adams, who has subsequently worked with Charles Strouse on the scores of Bye, Bye Birdie and Applause. Both Harnick and Adams deplore the closing of that resort).

It was also the scene of one of Harnick’s most devastating flops. A musical show which he had written with Ira Wallach and composer David Baker, and which had previously had a successful try-out in the late Margo Jones’ theatre in Dallas, was given a production the following summer at Green Mansions. “On a July night, 600 people in a place that should seat 400, no air conditioning, and it was stifling. By the end of the second act, we had 30 people with us.”

“But failure like that is important,” he says now. “Later, when Jerry and I teamed up to do The Body Beautiful and we saw all that work go down the drain in two months, I was prepared. I’d already had a worse experience. I’d been blooded.”

It was Hal Prince, who was to produce their Fiddler, who took the first real chance with the as-yet unsuccessful team of Bock and Harnick. Steve Sondheim, a close personal friend who has great admiration for Harnick’s work, has a vivid recollection of their first disaster. “After the newspapers came out with the bad notices, I sat there in Sardi’s commiserating with them, and they were so discouraged. I said ‘But it’s not hopeless. For one thing, your work was heard tonight by some people who know something!’ Sondheim had only recently made his debut as lyricist for the hit West Side Story, which Hal Prince had produced. “I’d seen Hal at the intermission of their opening and talked to him, and he’d told me that he didn’t think the show was going to be a success, but he loved Bock and Harnick’s music and lyrics. Just then, Hal walked into Sardi’s. I introduced him to the two of them. Now I’m not making myself out to be the great brain over all this, but the point is, later on, Hal offered me the job of writing the lyrics to Fiorello! and I turned it down, but I suggested Bock and Harnick. And to Hal’s credit, he took a chance on them.

“But then, Hal’s always taken chances on unknowns, you know. He hired Dick Adler and Jerry Ross to write Pajama Game—they were recommended to him and George Abbott by Frank Loesser. And later Hal hired Kander and Ebb to write Flora, The Red Menace, with Liza Minelli—that was her first show, too. Kander and Ebb eventually wrote Cabaret, and Bock and Harnick came up with Fiddler. That’s the terrific thing about Prince; he’s willing to gamble. Not many other producers will gamble all that money on unknowns, believe me, not in his hard-nosed business.”

Fiorello! was indeed a big chance for Bock and Harnick. The show was directed by George Abbott, from a book by Jerome Weidman. “We were very lucky there,” says Harnick. “It was Mr. Abbott’s last real success, and working with him taught us a lot, mostly about economy in writing. I’m a great believer in that—saying something well—in the least possible length. It’s the secret of good lyrics … at least, for me.”

The biography of New York’s colorful Mayor LaGuardia opened in 1959, and settled down to a long and profitable run. It won the Pulitzer Prize, and was an audience-pleaser. “I had this experience twice,” says Harnick. “With Fiorello! and with Fiddler. It was as though somebody was looking over my shoulder. With Fiorello! it was La Guardia himself. As I wrote, every so often, I would think ‘No, that’s not good enough. La Guardia wouldn’t be happy with that.’ He’s over my shoulder saying ‘No, no, you’ve got to do better than that…. ‘ The same thing happened with Fiddler, only that time it was the spirit of Sholom Aleichem. I kept thinking as I wrote, ‘No, no, he worked too hard on this material for me to settle for something so easy!”

The score of Fiorello! established Bock & Harnick as paid-up members of the Broadway scene, capable of writing a lovely ballad, “Till Tomorrow,” or a bright satiric number, “Politics and Poker.” The hit of the show—“Little Tin Box,” sung by a chorus of Tammany-type politicians, who happily recounted their exploits in the area of graft and corruption, proves Bock’s point about their ability to write under pressure. It was written out of town, and put into the show only a few days before the Broadway opening.

Fiorello! was a rare exhibit; a full-scale biography, set to music, of an actual public figure. Not often before, or since, has such a project succeeded. And the show was remarkable in its fidelity to the story of the man who red the funny papers over WNYC, loved to follow fire engines when they answered alarms, and managed to run New York not only colorfully, but efficiently.

Less than a year later, in 1960, there was another show, Tenderloin. “We started working on that right after our first hit,” says Harnick. “We opened in New Haven and it was disastrous. We had an emergency meeting that night. Mr. Abbott said, ‘I had a concept for this show, and it doesn’t work. Any ideas?’ And I looked at everybody in the hotel room, and I saw blank looks all around, and I suddenly thought, ‘My God, I don’t have any idea what this is all about, this whole show, except for the work I’ve done.’ So that the next show we were involved in, She Loves Me!—there I really started involving myself with the book, and working as closely as possible with Joe Masteroff, the book writer. Sometimes, I’m sure, to his great irritation. Since then, both Jerry and I have continued to work that way.”

When they discuss She Loves Me! both Bock and Harnick refer to it with affection. “It was the one I most enjoyed working on,” says Harnick. “On the stage, there was such a unity of idea … it was just beautiful.”

“A very special kind of musical,” says Bock, fondly.

From old Vienna and a charming caffee-mit-schlag romantic confectionery to the bitter-sweet chronicle of the impoverished Tevye and the rest of the ragged residents of Anatevka. Quite a change of scene. What caused it?

“Whenever we finish something,” says Bock, “we’ve always wanted to do an about-face and go somewhere else. To do something hopefully that will give us the opportunity to break new ground, to write fresh, or to explore territory we haven’t been in before. We’ve never sat down to write a score and made it a rule that we’ve got to come up with one or two hit songs. We concentrate on the needs of the book. When we started on Fiddler that was all that mattered.”

“For me,” says Harnick, “the book is the basis of the musical, the thing that makes it work. Without a good one, it’s hopeless.”

Some sort of alchemy was at work when Joe Stein and Bock and Harnick prepared the show; Bock and Harnick may not have been consciously writing hits, but the fact remains that works such as “Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” “Sunrise, Sunset,” and “To Life, To Life, L’Chaim!” go far beyond even the realm of what we call “standards.” The score for Fiddler is popular, and simultaneously classic.

“Jerry Robbins was instrumental in that happening,” says Bock. “We’d always hoped that the score would break through what appeared to be a special show, for certain people only, and begin to reach as many people as possible. That’s where Jerry Robbins accomplished so much for us. He kept asking the question—as he always does—what is this show about? And beyond the fact that it’s a family chronicle, he kept hammering away on the breakdown of tradition; on the inability of Tevye to cope with the changes that were occurring, not only in this little poor village, but the wide world as well. He guided us so that we kept that always in mind. And of course, the last song we wrote for the score really was the opening, because it was only after we had really dug into the show, and had it mostly finished, that we were able to express ‘Tradition!’—the opening chorus. Which made it the signpost, really, for the whole show. That was the circle. Mind you, that circle was a visual concept that Robbins always had in mind, from the start.”

In the past 15 years, when so much of American popular taste has favored folk-rock, electric guitars, and bubble-gum music, two Broadway show scores have achieved steady universal acceptance: Fiddler and The Sound of Music (others may argue that Man of La Mancha is in the same category, but that’s due only to “The Impossible Dream” which has made it big with baritones).

One can understand why the sunny Rodgers and Hammerstein saga of Maria and her happy charges has sold LP’s in the millions all over the world. Between Mary Martin and Julie Andrews on the wide-screen, those songs got “plugged” aplenty. But Fiddler?” It is hardly a “plug” score—and yet it has penetrated. One might logically expect that the lovely Bock and Harnick song “Sunrise, Sunset,” in which Tevye philosophically sings of the meaning of life at his daughter’s wedding, would have become de rigeur at Jewish weddings, along with “To Life, L’Chaim!”—a hearty drink and dance song. But when Zero Mostel did a guest-shot on the Dean Martin television show, eight years after the show’s opening, his solo had to be “If I Were A Rich Man,” which somehow, nobody considered ethnic. “For that universality, I believe Jerry Robbins is responsible,” Bock says today.

(Earlier, in response to a question as to which of Harnick’s lyrics from Fiddler he cherishes the most, Bock wrote “… I suppose I would have to pick one that was written under pressure, out of town. We were looking for a musical finish to a scene between Tevye and his wife, a song that would illustrate their very special relationship. I remember Sheldon coming into my hotel room and reading the lyric of “Do You Love Me?” He asked me what I thought of it. I could have hugged him. I think I did….”)

Fiddler became the huge success that it is despite a rather indifferent reception at its first performance out of town. “In Detroit, for example, the critic said it was an amateur production,” Bock seems fond of recalling. “And when it came to New York, we got mixed reviews.1 We were a slow hit, believe me.”

“God knows it’s been gratifying. But along with its accumulated success—I use that for lack of a better word,” Bock grins, “has come no insight as to how to do it again.”

Harnick takes an even less sanguine attitude toward the huge success of the show. “I was writing to a friend of mine who was congratulating me on Fiddler’s longevity, and I said ‘Thank you, it makes me literally feel like I’m king of the hospital.’”

Harnick is referring to the unpleasant fact that since the opening of Fiddler in 1964, the Broadway musical theatre has undergone a period of insanely-rising production cost, with less and less production. If it was tough to get an opening “break” back in the ’50s, for young tyro talents the ’70s scene is bleak. “I feel so lucky,” remarks Harnick. “I feel as though in a sense I’ve been walking along a cliff, and I’ve always taken a step backwards just before part of the cliff crumbles. For instance, I got in at the end of revues—New Faces and a couple of others. Now there are no more revues. My first book show was George Abbott’s last successful show. Fiddler was the last show that Robbins has done. He’s capable of many more, but for some reason, he’s chosen not to do them. I almost feel as though I came in and managed to make it just before the theatre dissolved. Jerry isn’t as pessimistic as I am about the future of musical comedy, or of Broadway itself. I am sure there’s a place for the live musical comedy—but perhaps, not any more in the style and shape it’s been for the past few years.”

Following Fiddler, Bock and Harnick attempted a completely different style of show—three short plays set to music. The Apple Tree was directed by Mike Nichols. “Again, something we had never done, a complete turn-about,” says Bock. The Apple Tree was well received, and had a successful run on Broadway in 1966-67.

Bock and Harnick’s next project was to occupy them for three years, and did not arrive on Broadway until the fall of 1970. The Rothschilds, on which they worked with author Sherman Yellen, is an adaptation of a biography of the famous banking family. The original producer of the show struggled for over two years to get backing for it. It wasn’t until he brought the project to Lester Osterman, another Broadway entrepreneur, that financing could be raised. In the midst of a Nixon recession, Osterman performed that heroic task of raising most of the show’s inflated costs— $850,000.

“God knows there were problems with that show,” says Harnick, a year later. “It’s by no means a great show. But there’s a taste, a certain level of invention and creativity. And most of all, we were not trying to insult anyone’s intelligence—and we did find an audience.”

Happily for all concerned, The Rothschilds ran for more than a year on Broadway, and is breaking records on tour throughout the West Coast. But all its costs have not been recouped, almost two years later. It becomes increasingly apparent that Harnick’s gloomy jest about his status as king of the hospital may be based on truth.

And so, for two craftsmen, who wish to exercise their considerable talents to enrich the American theatre (and themselves, in the process), the search for their next project goes on. They’d settle for practically anything as source material—a short-story, an old film, an original libretto written for the stage, perhaps? But so far, they’ve had no success.

Are they perhaps being too selective? “No!” says Bock. “Because when you say, ‘Okay, let’s do this,’ you now know that you’re committed to two or three years’ work, without a shadow of a doubt. So it’s not that you want to be careful, as much as you want to be thoroughly enthused, right or wrong, about the thing that’s going to occupy all your time from that moment on. When you say yes it should at least be with a sense of joy and energy and enthusiasm for … whatever it turns out to be. I personally need to feel that I can write lots of music for this one—I’m never going to be stuck. And Sheldon’s feeling is that our score will make a genuine contribution to the piece, that it will help, will inform—it will enhance it, and …” he hesitates, pondering the proper word, “… God willing, make it soar….”

And when that happy day arrives, when that piece of material crosses their threshold, when the book-writer has signed on, and the project has been launched, which will come first, the music or the lyrics?

Bock laughs. “I thought you’d never ask that. It’s both. We can work either way—which is great. It dispenses with the horror of waiting for the other person to finish. I write out all sorts of musical ideas, and then I tape them, and send them off to Shel. He may be at the shore—I’m in the city— whatever. Then he listens and responds by telling me which piece of mine interests him for which spot in the show. With us, it’s always wide open. Whoever gets an idea first passes it back to the other.”

Three years of work lie ahead—that’s assuming they do find a project. What will the Broadway theatre be like in say, 1974-75?

“I’m not sure,” says Harnick. “I think the musical will survive. In what shape or form, I’m not sure. Hair and Godspell, and The Me Nobody Knows are all examples of new approaches; so is Jesus Christ Superstar. They all have a kind of life on the stage; they don’t tell stories in the old accustomed way, in what McLuhan calls ‘the linear concept.’ My own conditioning makes me want to see a story on the stage, so that’s where my preference lies. But when I went to see Hair, I was so astonished; here was a show which broke all the rules I’d learned about writing for the theatre—and it was successful!”

“I am not depressed by what I see,” says Bock. “I try to keep an open ear, to listen to what’s happening. I think, I hope, that the kids will eventually begin to discover the music of the ’30s and ’40s, and we may have a resurgence of that. It’s encouraging that when I meet young writers, they all want to do their ‘own thing,’ but they’re also going back and studying the musical forms of the past fifteen, twenty, thirty years. I don’t think they’re winging it on an instinctive level.”

“The musical theatre will survive,” says Harnick, with just the faintest hint of prayer in his aspect. “Maybe not on Broadway—the expense. But somewhere else? I was thinking recently of that Brecht expression that goes ‘Where the need is greatest, then there’s something that will come along.’”

So, in fifteen years, they have come a considerable distance since the days when Bock wrote instant-musical numbers for Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca, and Harnick was taking sharp satiric pot-shots at censorship and narrow-mindedness with his “Boston Beguine.” Viewed in the perspective of the composers and lyricists who have come before them, Herbert, Kern, Romberg, Berlin, the Gershwins, Rodgers & Hart. Hammerstein, Arlen, Harburg, and all the others who have filled theatres, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick, along with their friend Stephen Sondheim, seem to be the last of a very proud line. Or, to use their own title, a “Tradition.”

“I hope that’s not so,” sighs Harnick.

Any words for neophytes who still plan to tackle New York?

“I once typed up a quote and put it over my desk,” says Harnick. “It read ‘Inspiration is the act of drawing up the chair to the writing desk.’ And O’Casey, I found out, had one which read, ‘Get on with the bloody job!’”

That may well be the secret of survival whether it be in Tevye’s Russian shtetl, in Fiorello La Guardia’s New York, in the Rothschild’s ghetto in Frankfurt, or on Broadway.