“… I CAN’T GET STARTED….

“You can count on the fingers of one hand and perhaps on the thumb and index finger of the other the number of our theatre composers whose melodic lines and harmonies are highly individual. There is no question that Vernon Duke must be considered one of these….”

So writes Mr. Ira Gershwin in his book Lyrics On Several Occasions, and it is a bit superfluous to add that Mr. Gershwin knows whereof he speaks, especially when he speaks of Vernon Duke, née Vladimir Dukelsky. Gershwin collaborated with Duke on the songs for Ziegfeld Follies, from which score came “I Can’t Get Started.”

“We did about thirty songs for that show, of which about eleven or twelve were used. I was very proud of the stuff I did with Vernon,” says R. Gershwin today. Among the other songs in the show were “Island in the West Indies,” “Words Without Music,” a beautiful “lost” ballad, and “That Moment of Moments.”

“Very talented, and very quick,” he continues. “He’d come in when we were working, and he’d grab me like a Russian bear—well, he was Russian, you know. ‘Ira—the greatest song I ever wrote!’ And he’d sit down and play it for me. I’d say ‘… Well … I …’ and then he’d say ‘All right, I’ll write another one!’ He was very prolific, and he made the fastest piano copy I ever saw. He could do a whole verse and refrain, a good piano copy, in twenty minutes—just put the whole thing down on paper….

“But Duke was always arguing—with everyone. Everyone he worked with—me, Yip Harburg—he always had some supposed grievance.”

Duke had worked with Harburg on the Broadway revue Walk A Little Faster. It was from that early Harburg-Duke collaboration that “April in Paris” emerged, to become the second of his great standards.

Bernard Herrmann, the composer-conductor, says “I could sum up Vernon Duke by saying that he really thought he was a Grand Duke—but there were times when he behaved like a Grand Duke’s coachman. He could be very vulgar, in many ways. But I always understood him, and I never took offense. He was a gifted composer, and a gifted songwriter. A marvelous pianist; the only one who could give him any competition there was his good friend George Gershwin.”

“He never really had the success that he should have had. It wasn’t because he hadn’t received the proper attention for his classical work. Even as a young man, he’d been singled out for praise in Europe by the leading musical authorities. But he was a very complicated man. I knew him from the time when he first came to America. I recorded his second symphony, his cello concerto, his violin concerto, many of his other works, so I understood a little of what the whole man was about. He had great success as a serious composer, h e had success as a popular composer, but I suppose it was because he never really won the sweepstakes—the jackpot. Perhaps because he had very little taste in picking librettos to work on; he didn’t know the difference between a good one and a bad one—but he certainly worked with good lyricists.

“In a way, I suppose with his popular music he was having his night out. But that never meant that he didn’t do fine work. After all, Offenbach was the same sort of composer—both classical and popular. Lehar was always trying to write grand opera.

“Vernon in many ways was really responsible for the lack of his own success. He carried on feuds with lots of people. The one with Stravinsky is well known, and he also had one with Stokowski. I tried to get Stokowski to play one of Duke’s concert works—‘Ode To The Milky Way,’ and Stokowski said ‘I just don’t like it—I’m glad you do.’ So Duke held me responsible for Stokowski not playing it. I told Duke I’d tried, but it was no use. I tried Stokowski again. Still no use. When I saw Stokowski in London a couple of years ago, he said to me ‘You know that wonderful piece you once showed me, the one about the Milky Way?’ Now it’s something ‘wonderful’—do you see what I mean about irony?”

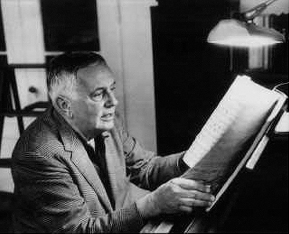

Vernon Duke

“I didn’t see him for the last five years of his life because of something he took offense at—not of what I said—but of what my former wife said. She made him a soup he liked—but she didn’t make it the way he liked it! Something as trivial as that….

“When he got married, I sent him a letter. I said ‘Even royal dukes in Russia on their nuptial days forgive all the serfs, and release them from jail. Why don’t you talk to your old friend?’ he never answered. Because my wife didn’t make his soup properly—or what? I never knew,” says Herrmann.

Along with “I Can’t Get Started” and “April in Paris,” Duke had a third huge song hit, from the Broadway show Cabin in the Sky—the rollicking “Taking a Chance on Love.”

“That was a very happy accident,” recalls Arthur Lewis, the producer, whose father, Albert Lewis, produced that show in 1940. “We were having trouble with a scene change, just before opening. Ethel Waters, our star, had to have some sort of a song in one, before the curtains, while we made the change backstage. We needed something with impact. Vernon had been coming up with songs that didn’t fit that need, but he came in one night with a song called ‘Fooling Around With Love,’ that he’d written with Ted Fetter for something else. Well, when he played us that, everybody jumped at it. There was a big legal problem involved—Fetter’s lyric had to be rewritten by John LaTouche, our lyricist, and it was very difficult to iron out the problem of interpolation. Duke and LaTouche had a contract that specified nobody else’s songs could be used, and here was a song written by Duke with Fetter. Finally we got it all straightened out, LaTouche changed the title to ‘Taking a Chance on Love,’ and on opening night, when Ethel came out and sang it, there was just no way to follow it! She sang five choruses—the audience wouldn’t let her leave the stage. Ethel finally ad-libbed a little closing couplet—something to the effect that she didn’t have any more words. A huge hit, that song—and it’s always been one since that night. So ironic. If we hadn’t been in a spot with some scenery, that song might still be stuck away somewhere in Vernon’s trunk!”

“One of the things that gave Duke his greatest thrill,” says Herrmann, “was that his show Cabin in the Sky ran longer in France than it did in New York. There they did a much richer and more sophisticated production— more complicated, and as he said to me, ‘There, they have real choruses, who can sing.’ But that was part of the complexity of the man,” he adds. “That split personality. Up at ASCAP, he was only regarded by how well he was doing on Broadway—and all Duke was really worried about was how well he was doing up in Boston, with the symphony orchestra.”

In the years that followed Cabin in the Sky, Duke’s career as a popular songwriter had more than the customary ratio of flop to success enjoyed by his peers. He and LaTouche wrote a score for Eddie Cantor’s starring vehicle, Banjo Eyes. The show was a hit, but closed abruptly because of Cantor’s physical problems. There were to be others, such as “Sadie Thompson,” which he wrote with Howard Dietz, that were less-than-hits. After the war, during which he wrote a score for the Coast Guard—in which he served— called Tars and Spars, Duke worked on various collected revues, and contributed songs to a pair of minor Hollywood musicals. It was while he was working in Hollywood that he met the young Bobby Short; pianist, singer, pop-song interpreter par excellence.

“I was working in a place called the Club Gala, above Sunset,” says Short. “Vernon came in one night. With no urging whatsoever, he got up from his table—he was a supreme egotist—came over to the piano and sat down and played some of his songs. I sang them. He became a big fan of mine, and it was mutual. I love Vernon’s music. I loved it before I was aware who’d written it.”

“When I was just a kid, I heard a song that he had written for a Broadway show called Now, and I was immediately drawn to it. Then later on, when I was 13 or 14, I remember being attracted to ‘April in Paris.’ He was remarkable. His sense of harmony was something that America hadn’t ever heard before in popular music—it was a whole different approach!

“I know Vernon is well-known for putting down other composers,” Short continues, “but never with me. He’d always bring me stuff by other composers, Bo Bergersen, or Bart Howard, and discuss their talents, not his. I learned several very obscure Gershwin songs from him—you know, he was a great admirer of Gershwin’s work,1—and he came to New York one day when I moved East and brought with him twelve more obscure Gershwin songs. ‘Record these,’ he said. Never his own….

“I can tell you something else about Duke,” says Short. “As exacting as he might have been, and as ignorant as I was about what he’d written down in his music—because I don’t read notes—Vernon never took it upon himself to say ‘Look, you’ve got those last eight bars wrong.’ Never told me. I’d always find it out some other way—by hearing it played by somebody else. I know for a fact he heard me do some of his songs wrong—but he never corrected me. He left that up to me to figure it out by myself. And believe me, I’ve had half-baked composers with one or two songs to their credit come to me, screaming and yelling about this change, or that phrase being played wrong. Not Vernon. He and Cole Porter were alike about that….

“Great ladies’ man. Adored eating and drinking—extremely intelligent, literate. Wrote well. Snobbish, true, and a little mean, because he never quite achieved the success he should have had, I guess. A little bitter because of that,” says Short.

“You know, I never liked his song ‘I Can’t Get Started’ until I heard him play it. That famous old Bunny Berigan record, as famous as it was, and as much fun as it was to hear, never really captured the essence of the musicality that Duke had applied to the melody of that song. Never. I then heard Vernon accompanying Hildegarde one night when she sang it, and I also have a record he made of it, playing it on the piano alone. Vernon plays it so poignantly, because it’s a sad, bitter-sweet song. Very much like Cole Porter’s ‘Why Shouldn’t I?’ I sit here at night and play both of those—when I get to Vernon’s ‘I Can’t Get Started,’ people always chuckle at Ira Gershwin’s lyrics, and they smile—but underneath it all, it is a very sad song that really says—‘I can’t get started with you.’”

Vernon Duke died several years ago. “Poor Duke,” said Herrmann, his old friend. “Lung cancer … and he never smoked.”