IF YOU’VE BEEN fortunate enough to listen to E. Y. Harburg sing his own lyrics and discuss the hows and whys of such classics as “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?,” “Over the Rainbow,” “How Are Things in Glocca Morra?,” and “April in Paris,” either in the YMHA auditorium in Manhattan, or on various television shows, you won’t need to be reminded of the electric excitement and the amazing nostalgic warmth that he communicates. He lights up the stage and the tube with a high-voltage rating of near-incandescence.

“Yip,” as he has been known ever since the days when he and Ira Gershwin sat next to each other in classes at City College, is a stocky, vigorous gentleman who shows little physical evidence of becoming seventy-five at his next birthday. Since the bleak days of 1932, when he wrote “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?,” he has been turning out top-rate songs with a variety of our best composers—Harold Arlen, Jerome Kern, Vernon Duke, Arthur Schwartz, Burton Lane, Earl Robinson. He’s also a complete man of the theatre, having often developed his own story ideas into musical comedies (he and Fred Saidy were co-authors of Finian’s Rainbow), and during his Hollywood tour of duty he added to Metro’s yearly profit figures by producing a batch of profitable film musicals.

There may not be any valid course in lyric-writing available to the tyro—in fact (as Lee Adams, another wordsmith of considerable talent, has remarked), it’s more than likely that along with playwriting, or any other creative work with words, songwriting is a craft that is simply unteachable. Harburg is blunt on the subject. “We never knew anything about schools,” he says, rocking back and forth on the porch of his comfortable summer home on Martha’s Vineyard. “We just got up and wrote, that’s all. Like Topsy—kind of growed. Nowadays there are so many different courses in the universities. I personally think it’s a lot of nonsense. The bright kids get lost in a welter of formulas, clichés. Not that I don’t say you must have some analytical basis and some awareness, but I think that in every age there are only a few people born with talent. You can’t make ’em.”

What follows, then, in Yip’s own words, is a compound of his own life story, a goodly helping of pragmatic know-how, and a sparkling of philosophy. A short course, perhaps, but long in content.

Yip—you’re on.

“How did I start? I wrote all the parodies of the day. Name every old song, and I had a parody for it. That gave you status—there was no other way. No money. You were a slum kid and you had no identity. And suddenly you could hear a bleacher full of little gangsters singing your song…. That’s how it started.

“I come from a rough area, right there on the East Side—the East River, with all the derelicts, docks, lots of sailors and gangs. There wasn’t any such thing as an East River Drive down there. This was before World War I. Italian gangs on Mulberry Street—we used to play them in baseball. I was on the Tompkins Square Park team; we won the New York State championship. And then there were the Irish, a little further up on 14th Street. Plenty of gang fights. Those of us who were a little more sensitive and didn’t care for that so much were directing ourselves to the settlement houses, like the Henry Street Settlement. Wonderful places. They took the kids under their wing. They had wonderful social directors. They had clubs, athletic clubs, literary clubs. I belonged to a literary dramatic club. We were putting on plays, and that excited me.

“The public schools were better then, too. I went to P.S. 64, on Avenue B and Ninth Street. Great teachers—they were aware of the poverty conditions of the kids they were teaching. I had an English teacher—his name comes back to me as though it was yesterday: Ed Gillesper. I’d write something for the school newspaper, or a composition, and he’d read it and see something funny in it, and say, ‘Harburg, come up here and read it to the class.’ I’d read, and there would be twenty-odd kids laughing out loud, and, by God, that was really something. I’d tell myself, ‘I want to repeat this experience!’

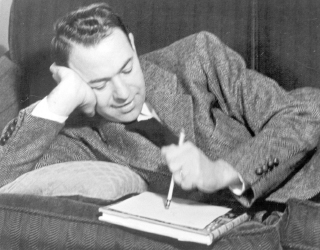

E. Y. Harburg

“We’d do shows at the settlement house, or in school, and I’d usually get parts. I found I had the ability to act and to write my own stuff. Scrounging around for costumes, putting on shows—it was great. We were poor, always out in the street with our furniture, and never knowing if the next rent would be paid. But I had an exciting time. More fun than I ever had in Hollywood. It was real. If you wanted to play a basketball game, you had to make the equipment yourself. No basketball, no bat or ball— you made everything, improvised.

“Luckily, there was City College, which was free. And attached to it was Townsend Harris, a high school that crammed a four-year course into three. I went there, and earned money at night lighting street lamps. In those days they’d employ kids for $3.06 a week to go around at night and turn on the lamps. I was twelve. They gave me a three or four-mile route. I’d put the lights on when dusk set in, and then I had to get up at three or four in the morning and go out and turn ’em off! Earned enough for food and whatever else I needed. Worked my way through college, too. All kinds of jobs. God, you worked every minute of the day!

“In high school I worked on the newspaper. Began writing things with more sophistication—light verse. By that time I’d begun to know about W. S. Gilbert. When I got to City College, I began to send in stuff I’d written to ‘The Conning Tower,’ a column Franklin P. Adams ran in the old World, a hell of a good paper. Verses. You see, at that time everyone was writing light verse—sonnets, acrostics, things like that. Dorothy Parker, Deems Taylor, Edna St. Vincent Millay, George Kaufman, Marc Connelly, you name them. They’d write that sort of thing, and had a lot of fun doing it. When Adams accepted things of mine and I saw my name in his column, along with Marc Connelly’s or Dorothy Parker’s—well, it gave me such a lift I felt I could conquer anything! Not financially, of course. I never got paid until I started sending verse to some of the magazines—Judge and Life and so on. Then I’d get $10 checks, $15 checks. Which meant a great deal.

“My classmate at college was Ira Gershwin. We sat next to each other— G, H, you see. We began collaborating on a column for the City College newspaper. Yip and Gersh. He was always interested in light verse, too. He introduced me to a lot of things that I’d not had access to. The Gershwins weren’t poor—they had restaurants. George was a kid then, just a snip of a kid, and Ira sort of sloughed him off because George didn’t care too much about education and had dropped out of school. I remember once going up to the Gershwins’ to hear the Victrola—that was a very new thing, Victrola records. That was the first time I heard W. S. Gilbert’s lyrics set to Sullivan’s music. Up to that time I thought he was simply a poet! Ira played Pinafore for me, and I had my eyes opened. I was starry-eyed for days. I couldn’t sleep at night. It was that music—and the satire that came out with all the emotion that I never dreamed of before when I read the thing cold in print!

“Ira dropped out in sophomore year. I suppose I should have taken a B.A. degree, but I didn’t. I went on to a B.S. I took all the damned hard courses like integral calculus. Nothing like the so-called ‘crap courses.’

“When I got out of college, I didn’t pursue poetry. That was work for a dilettante—nobody made a living at that. That’s for fun, that’s a sideline, you don’t earn money that way, I used to think. Money is made by the sweat of your brow. This is the old Puritan ethic that we’re brought up with. You’ve got to do something real nasty, dirty, get calluses—you don’t just sit and write. Because you couldn’t live on $10 checks for poetry, could you?

“So I went into the electrical-supply business with a college classmate. I don’t know why he wanted me as a partner. Maybe it was because by that time I was something of a local celebrity with my poems. For the next few years we made a lot of money and I hated it. I hated every moment of it. I’d signed a contract saying I wasn’t going to spend any time except on the business—the guys who put up the money for the business probably figured I’d go off and neglect it.

“But the economy saved me. The capitalists saved me in 1929, just as we were worth, oh, about a quarter of a million dollars. Bang! The whole thing blew up, I was left with a pencil, and finally had to write for a living. As I told Studs Terkel once, what was the Depression for most people was for me a life-saver!

“I called up my friend Ira. By that time he and George had a lot of shows and had become big names in the business. Ira introduced me to Jay Gorney, and we began writing songs. I was penniless—in fact, I owed a lot of money. And one of the first songs I wrote with Jay was ‘Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?’ for a show called Americana that J. P. McEvoy was producing.

“McEvoy was a satirist. He was writing this show, which was to be about the Forgotten Man. Roosevelt had just made that phrase popular. McEvoy wrote the book, and I did the lyrics. I started writing with Vincent Youmans, but he left. Then I worked with three or four other composers,1 because we had to get it done in a short time. But the show turned out to be very good. I think it was the first time ballet dancing was used in a Broadway revue; we had the Charles Weidman dancers, with Doris Humphrey.

“It was a terrible period. You couldn’t walk along the street without crying, without seeing people standing in breadlines, so miserable. Brokers and people who’d been wealthy, begging. ‘Can you spare a dime?’ … that was for a cup of coffee. That’s what the big thing was, a dime could keep you alive for a few days.

“When Jay played me the tune he had, I thought of that phrase ‘Can you spare a dime?’ It kept running through my mind as I was walking the streets. And by putting the word ‘brother’ to the line, I got started on it.

“But I thought that lyric out very carefully. I didn’t make it a maudlin lyric of a guy begging. I made it into a commentary. That may sound rhetorical, but it’s true. It was about the fellow who works, the fellow who builds, who makes the railroads and the houses—and he’s left empty-handed. How come? How did this happen? Didn’t I fight the wars, didn’t I bear the gun, didn’t I plow the earth? In other words, the fellow who produces is the fellow who’s left empty-handed at the end.

“I think that lyric lives because it doesn’t tackle the thing in a maudlin way. It’s not a hand-out lyric, like a lot of the old English ballads; they’re lachrymose, almost begging. This is a man proud of what he’s done, but bewildered that this country with its dream could do this to him. I think a lyric first of all hits you emotionally, directly. And this did it because of the music, and because the fellow wasn’t being petty, or small, or complaining.”

(Jay Gorney says, “Several years later, when I’d come back from Hollywood, Lee Shubert sent for me and said, ‘Good to see you, Gorney. What I wanted to ask you is, do you have another song like “Mister, Will You Give Me Ten Cents?”’ But his brother J. J. never shared Lee’s enthusiasm. Whenever anyone mentioned the song, he’d say ‘I don’t like it. It’s too sordid!’)

“I kept on writing after that; you could say I was launched. Gorney and I wrote songs for an Earl Carroll Vanities. At that time Carroll specialized in selling his beautiful girls. He used a novelty gimmick: ‘Through these portals pass the most beautiful girls in the world!’ When I first saw these most beautiful girls rehearsing, I realized the effect of theatrical showmanship. Carroll’s girls were really ugly—dogs—but on the stage, made up, in costume, with lighting and special effects, he could see them to the audience. People believed that slogan of his!

“I did two shows with him—one a Vanities, the other a Sketchbook—and then in 1932 I did a revue with Bea Lillie and Bobby Clark called Walk a Little Faster, and some songs for Willie Howard and Bob Hope—Hope’s first Broadway show, a revue called Ballyhoo. That’s when I discovered that I could write comedy songs. That really titillated me the most—the comedy, the satirical idea—because with that sort of song I felt more at home. After all, my earliest education at that was from Gilbert and Sullivan.

“Gorney had gone off to work in Hollywood with Lew Brown, and I was by now working steadily with Harold Arlen and with the late Vernon Duke.

“Billy Rose was doing a play by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, The Great Magoo, and he called and said, ‘We need a song here for a guy who’s a Coney Island barker. A very cynical guy who falls in love and finds that the world is not all Coney Island—not papier-mâché and lights and that sort of gaudy stuff. But it’s got to be a love song.’ Well, I tried to think of a cynical love story, something that this kind of a guy would sing. But I could never really be cynical. I could see life in all its totality, its reality. In a song I wrote for another show at that time, I wrote that it’s fun to be fooled. That was a love song also. But I doubt that I can ever say ‘I love you’ head-on— it’s not the way I think. For me, the task is never to say the thing directly, and yet to say it—to think in a curve, so to speak. In ‘Fun To Be Fooled’ I was saying life is all being fooled, we are all being fooled by it, but while it’s happening it’s a lot of fun. I think it’s a lot of fun. I think it’s a lovely excursion, and I’m glad I got a ticket for this short cruise, and that’s all.

“So when it came to the other song, it was an extension of that same idea. I called it ‘It’s Only a Paper Moon.’ The idea there was that the guy says to the girl the moon is made of paper, it’s hanging over a cardboard tree, but there’s a saving grace called love. Without it, life is all a honkytonk parade. In other words, it’s not make-believe as long as someone believes in it. The Great Magoo was a failure, but that song became a big hit.

“So was ‘April in Paris,’ which I wrote with Vernon Duke.2 That lyric has a very special quality. First of all, I think it captures Paris in a way that only French people have been able to do. And then, it’s not about simply being in love in Paris but about wanting to be in love anywhere. Again, I tried to avoid the cliché. This is a person who has never been in love, never wanted to be in love. He goes to Paris and, for the first time, experiences wanting to be in love with somebody. He wants to run to somebody. Paris has opened him up for the first time.

“I met Vernon Duke through George Gershwin. After Gorney went to California, I started writing with various composers, and I began to realize different types of songs that existed. It was fine for me because it allowed me to learn my own abilities. Vernon had just come over from Europe. He was a Russian—his real name was Vladimir Dukelsky—and he was very far advanced in his music. Very serious composer. As Dukelsky, his symphonic works were performed in concert halls. In Europe he’d worked with Diaghilev, writing ballets, and he was very avant-garde for this period, the mid-’30s. George Gershwin was very impressed with Duke’s music. I suppose you could say he learned a lot from Vernon.

“I liked Vernon’s facility. He was fast and very sophisticated, almost too sophisticated for Broadway. Walk a Little Faster had some very smart stuff in it. In fact, that’s when I bounced out of the bread-and-butter stage into sophistication. My light-verse background popped up to reinforce me, and I could write much easier with Vernon than I could with some of the others. It was light, and airy, and very smart.

“Vernon brought with him all of that Noel Coward/Diaghilev/ Paris/Russia background. He was a global guy with an ability to articulate the English language that was very interesting. A whole new world for me. He could drive you crazy, and he could also open up a new vista. Maybe it was a little bit chi-chi and decorative, but with my pumpernickel background and his orchid tunes we made a wonderful marriage. Maybe we were a strange mixture. We didn’t compromise with each other. I applied the everyday down-deep things that concerned humanity to his sense of style and grace, and I think it gave our songs an almost classic feeling, along with some humor. We came together at a certain point, and for a while it was fine. He satisfied my sense of light verse and the need for sophistication.

“Later I felt that his music lacked the essential theatricalism and the histrionics that writing for shows demanded—the drama, the emotions. So gradually I gravitated more and more to Harold Arlen.

“Ira Gershwin and I collaborated with Harold on a score for Life Begins at 8:40. That was when I first got to know Harold as a craftsman. There were Ira and I working together again—a nice nostalgic thing. We wrote “Fun To Be Fooled” and “You’re a Builder Upper” and “Let’s Take a Walk Around the Block,” and it was truly a joyous collaboration, a very happy few months. Ira would come in with one idea, I’d come in with an idea, Harold would come in with a tune. Lovely.

“After Life Begins at 8:40, Harold went out to California to write music for movies with Ted Koehler, with whom he’d written ‘Stormy Weather.’ Carl Laemmle, who ran Universal Pictures, came to New York and took a shine to my work, and gave me a contract to come out to his studio and do musicals there. After Harold’s contract was up and mine at Universal had run out, there was an opening at Warner Brothers, and we were teamed up again to do some pictures there. And from then on, we’ve worked together, on and off.3

“Things began to get very touch around Hollywood. I got an idea for a book show, Hooray for What?, that would be a satire against war, and Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse wrote it. Harold and I did the score, and Ed Wynn played the lead, and it was very successful. Ed played an inventor who’d come up with a gas that would end wars. That story would be much more pertinent now than it was in 1937, I’m sure. We had great notices and ran a year, which in those days was a very good run. I’ve often thought it should be done again, now.

“When Harold and I started writing the score for The Wizard of Oz, we weren’t thinking in terms of classics. We were just doing work, earning a living and liking what we were doing, trying for a hit song or two. We never thought of posterity. We were very excited about the film, we loved it. For the first time we’d gotten something that we both felt had the feeling of being fun. It was a chance to express ourselves in terms we’d never been offered before. I loved the idea of having the freedom to do lyrics that were not just songs but scenes. That was our own idea, to take some of the book and do some of the scenes in complete verse, such as the scenes in Munchkin Land. It gave me wider scope. Not just thirty-two-bar songs, but what would amount to the acting out of entire scenes, dialogue in verse and set to Harold’s modern music. All of that had to be thought out by us and then brought in and shown to the director so he could see what we were getting at. Things like the three Lullaby girls, and the three tough kids who represented the Lollipop Guild. And the Coroner, who came to avow that the Witch was dead, sincerely dead. All of that was thought up by us, it wasn’t in the book. Even a thing like ‘Over the Rainbow’—there was no such thing as a rainbow mentioned in the book.4

“When we brought in the song, all we were thinking about was a little girl who was in trouble with her folks, in conflict with them, at an age when she wanted to run away, and knowing that somewhere, someplace, there was a colorful land that wasn’t this arid flat plain of Kansas. She remembered a little verse from her childhood that mentioned a colorful place where bluebirds fly. The only thing she’d probably ever seen that was colorful was the rainbow. And that gave them the idea of doing the whole first part of the picture—when she’s in Kansas—in sepia, black-and-white. And then when she got to Munchkin Land, the fairyland place, it became colorful. This whole new country was rainbow country.

“When you write music and lyrics, you have to think of all those things. You think of what’s going to happen on screen or on stage—the action, what you can do pictorially—so that you really direct the lyric toward the pragmatic medium. If you can do that, it’s working in showmanship terms, to work with your lyrics and music as a director would work, and as a book-writer would, and still have that song written in such a way that it could step out of the histrionic medium and plot—which it accelerates— and be made to flourish and blossom. In other words, if the song can be taken out of the picture and still have a life of its own, be a popular hit, then you have accomplished the real premise of songwriting. This is a pretty hard thing to do.

“Of course, when you get a man like Harold Arlen working with you, it’s easier. Later on I found out that Burton Lane could function with me, too, but in a different way. And George Gershwin always was tremendous at this sort of thing.

“What made ‘Over the Rainbow’ such a success? Well, hindsight always furnishes you with a lot of material for analysis. First, we had the luck to have a good picture. Many great tunes and fine songs have been lost and have faded away in the framework of shows that didn’t stand up. Harold and I have had some beautiful songs in shows that just didn’t make it. And then we had a book based on a classic. Wizard of Oz was known to so many people. And, then, of course, there was Judy Garland. She found an identity with all the young children. One of the great voices of the century, one of the great entertainers. She had an emotional quality that very, very few voices ever had. The whole world seemed to have an empathy with her, not only because of the way she sang that song but because her own life was the epitome of it. This girl who was so loved, and who had everything in the world that she’d reached out for, was the unhappiest. She could own everything that she reached for, and yet couldn’t touch the thing, somehow, that her soul wanted. I think people must have felt the condition of her spirit. Her whole life, almost like a Dostoevsky novel, seemed to fit this beautiful little child’s song that had color and gaiety and beauty and hope … and yet she was so hopeless. That must have had a lot to do with the song bringing into everybody’s life almost the sadness of being a human being.

“You’re talking about a big giant of a composer writing a hell of a great tune … and I happened to take a hitchhike on his coattails.

“Show business is a strange thing. Right after we did the score to The Wizard of Oz, Harold and I went through a period where we didn’t get too much work. Metro called us back to work on a song for Groucho Marx which he did in At the Circus—it was ‘Lydia, the Tattooed Lady.’ Then Harold went off to write with Johnny Mercer on some other films—he felt he needed a change, and so did I—so I teamed up with Burt Lane on the score of Hold On to Your Hats, which Al Jolson starred in on the stage. Burt and I wrote what I’ve always thought was a very fine score. The show had a respectable run, but Al got itchy to leave for Florida—he missed his horse-racing—and he closed up the show. Al was that kind of a guy.

“Then I went back to Metro, this time as a producer-writer. I worked on the film version of Meet the People, and Harold and I wrote songs for the film of the Broadway hit Cabin the Sky; we did ‘Happiness Is Just a Thing Called Joe’ and ‘Life’s Full of Consequences.’

“Whenever the studio needed a song for a musical, they’d get hold of me and I’d get hold of Burt Lane. We did one for Frank Sinatra. I think it’s the first that was ever written for him to do in a picture—‘Poor You.’

“I was always very involved in politics, very politically oriented. I gave it a lot of time. I gave up jobs whenever there was something to fight for that I thought was right. In 1944 I spent a lot of time writing material to help get Franklin Roosevelt re-elected. I wrote a song with Earl Robinson called ‘The Free and Equal Blues.’ We did that on a national radio show, four networks—all the big names of show business, and the, for ten minutes at the end, Roosevelt himself.

“Harold and I got together again, this time on the score for Bloomer Girl. That was also a political subject. It dealt with the rights of women and Negroes—all tied up, indivisible. It had a Civil War background, and the story had to do with runaway slaves and Mrs. Bloomer’s fight for recognition of woman’s equality.

“There were so many new issues coming up with Roosevelt in those yeas, and we were trying to deal with the inherent fear of change—to show that whenever a new idea or a new change in society arises, there’ll always be a majority that will fight you, that will call you a dirty radical or a Red. Or a Christian. I love Bernard Shaw’s Androcles and the Lion, because Shaw took such delight in showing how, when Christianity arose, the Romans considered the Christians such radicals, so dangerous, that they had to be thrown to the lions.

“Eventually, in time, they had to get around to me. I was blacklisted. I didn’t mind. I think I’m a rebel by birth. I contest anything that is unjust, that causes suffering for humanity. My feeling about that is so great that I don’t think I could live with myself if I weren’t honest.

“I had trouble all the time at Metro, with executives. They’d call me in and say, ‘Now look, we want a show here that has no messages. Messages are for Western Union. We like your stuff, but you’re inclined to be too much on the barricades. Let’s get down to the entertainment.’ Sam Katz, Arthur Fred … they were always worried about me. But I always felt my power. They had to have me. If they wanted funny songs, there weren’t too many around that could do them. If they wanted songs with some kind of class and quality—well, there weren’t too many guys around like Larry Hart and the Gershwins. There were just a few of us, maybe five or six. I figured, hell, if they wanted me, they’d have to endure my politics.

“My wife thinks it was because I was liked—and she maintains I have a certain spell-binding charm, with men especially. Now that I look back on those days, I think she may be right. They were all frightened of my ideas, but they all liked me. All of them, even Louis Mayer. Maybe it was some sort of chemistry. I was never a wheeler-dealer, never a businessman per se, and they always thought I was a pretty poetic sort of guy and not a conspirator. They couldn’t connect me with conspiratorial things, somehow. They always thought of me as living in a fairyland world of leprechauns and rainbows … therefore, I couldn’t really throw a bomb. And I’d also always laugh at their fears. I’d joke with them, I’d kid them, I’d quote George Bernard Shaw. But in the end it wasn’t so sunny—I was blacklisted.

“But then, I had the theatre. I could run back to Broadway. I went back with Finian’s Rainbow in 1947. I’d had the idea for the story and had written it with Fred Saidy, after doing a lot of research. Not only all the Irish folk songs and the background, but I went down to Kentucky and went into the mountains, long before that became popular, to immerse myself in the folk music and the colorful speech they use.

“I really loved Finian’s Rainbow. I was so wrapped up in it. The whole thing had come to me as two separate ideas which somehow worked together. I’d wanted to do a show about a fellow who turns black, down South; and I’d always loved the idea about a leprechaun with a pot of gold. And when Saidy and I had written it all—bang, it was there. It was right. No rewrites. Just the way I’d always wanted it to be.

“Burton Lane and I worked on that score in Hollywood. Burt had a gaiety and a bounce, and he bubbled. He was really very much akin to George Gershwin in his lighter vein. He struck a very responsive chord in me because his music gave me the chance to do the kind of light, airy, humorous-satiric things that I’ve always loved to do.5 He has zest, life—he has verve. He has upbeat in all of his music.

“Another thing about Burt is that he’s very, very concerned about getting the right thing for you, and he’s very critical of himself. Burt will never fight you for a tune. He’s always changing, and he’s always saying, ‘Is this right, or isn’t it?’ He always wants to try and get something better. But that’s true of any good writer, isn’t it? The writer who isn’t a hack is always afraid of what he’s written. Never gets incensed, always feels that criticism is valid. Never knowing, and never sure. It’s the hack who’s always sure of what he’s written.

“From Finian came ‘How Are Things in Glocca Morra?’ I had a situation where there was the father who’d left Ireland for America, and brought his daughter to the South. I wanted to write a song that would indicate how she wanted to get him back to Ireland. I’d done a lot of research in Irish poetry and, for some reason, had become imbued with the sound of those two names, Glocca and Morra. Why, I don’t know. Probably because they sounded romantic, mysterious, Gaelic. Also because Glocca seemed like a lucky name—in fact, in German the word is Gluck. Lucky tomorrow … that’s how it seemed to me.

“I told Burt to write an Irish tune, but to make it his own Irish tune. I didn’t want to box him in; I wanted him to roam free, not restrict him. Well, he wrote five or six tunes, but none was right. Neither of us liked them. I’d given him one line—‘There’s a glen in Glocca Morra’—and finally he came up with one we both liked. I said, ‘Burt, yu know the Irish always add a little bit,’ so we did that too. I was influenced by old Irish writing; I added ‘Killybeg, Kildare…. ‘ And then we found the notion of a lark singing somewhere off, and the girl saying, ‘That’s the same skylark music we have in Ireland, it must be an Irish bird, a Glocca Morra bird.’ And out of that came the idea that she would ask the bird, ‘How are things in Glocca Morra?’ Out of the title came the cue, the sound of the bird singing, and then the verse of the song. It’s what I’ve always tried to do, to get away from the direct approach and find another way of getting into the material, one that would be stage writing, where the song was actually a scene. That kind of songwriting is really dramaturgy.

“Burt did a great job on that show. He used the archaic spiritual things, and instead of saying, ‘On that great day,’ which was a typical spiritual phrase, I just twisted it into a political comment by making it ‘Great come-and-get-it day.’ Then there was another song which had more of a Negro feeling to it, ‘That Old Devil Moon.’ We had written another ballad before this called ‘We Only Pass This Way One Time.’ Harold Arlen came over to my house one night and heard what Burt and I had written, all of it, and said he thought that was the only weak song in the show. So I had Burt play him a tune he’d been fooling around with—it was to be ‘Old Devil Moon,’ though it had another lyric; we’d written it for a movie, but never used it. Harold said, ‘How can you equate these two? The one is champion stuff, and the other is lightweight!’ That decided me; I tossed out the first song and the lyric to the other, and started looking for an idea, something that had to do with witchcraft, something eerie, with overtones of voodoo. Eventually it became ‘Old Devil Moon.’ Strangely constructed. It doesn’t have a verse, and it isn’t the ordinary thirty-two-bar song at all, but it became very popular. That’s what made it a great song—it was original.

“I think I’ve been very lucky to work with men who were really original craftsmen. Men like Arlen, who are not satisfied with merely turning out tunes. Always trying. Burton Lane is certainly the same, as far as that is concerned. Vernon Duke was also dissatisfied with the ordinary. Sammy Fain6 was, I would say, more on the common denominator, but he had a great sense of lovely melody which also seems to be part of me, too. I like a completely outgoing melodic phrase such as Kern wrote, although it was harder for me to write to the Kern sweetness and light.7 But there’s some specific hangover in me that makes me love that kind of melody…. And the thing is that what I like to do is to test myself in almost every direction. I don’t like to stay in one spot. I like to try a new tangent, to explore. That’s why I’ll never be a great golfer, because I’ve got to keep changing my game. I could be a hell of a golfer, but I can’t stick to one thing! I say, ‘No, there must be something else!’ It’s a kind of necessity for variety.

“I’ve always attacked everything with the same amateurish fear that I had at the beginning—of not knowing where it’s going to come from … will it come? I know that if I sit down the pen will flow somewhere and the words will come, but I’ve always had great concern and trepidation that I don’t know if I’m going to do this, I don’t know where it’s going to come from. Maybe it’s some form of perfectionism—you’re afraid you won’t get the very top of yourself.

“Gershwin didn’t have that problem. Gershwin just sat down and was sure of himself. George was an originator. George’s music almost needed no lyrics; he understood the theatre so well that he could make a humorous scene laughable and funny and titillating with just his music alone. Right off the bat. He had that real genius and affinity for the stage. You hear his songs, they can’t be anyone else’s. You listen to another song-writer, the melody might be anyone’s. But I know a Gershwin tune, I know a Cole Porter tune, I know a Jerome Kern tune, I know a Harold Arlen tune. They’re not imitators. They have their own hallmark, they’re uniquely their own.

“Writing with different composers is always a different psychological experience. Each one has his own approach to creation. To know their idiosyncrasies and to be able to get the best out of each one is fascinating. Each composer brings out a different aspect in your work. Duke, with his very sophisticated music for that time, the late ’30s and ’40s, demanded a certain kind of lyric. Vernon’s particular personality also required that you talk to him in a certain way, that your criticism and objections be registered in a diplomatic way that would neither reject nor demolish him.

“Lots of times the composer will give you a whole tune, and if he’s sensitive to your lyrical quality—for example, Harold Arlen is very sensitive to what will fit his melody—and you give him a title or a first line, and if he doesn’t agree, he’ll tell you. But it’s the way he tells you, and how you respond … and what your coefficient of acceptability is toward criticism. That is what your relationships with all these men depend on.

“It’s diplomacy, it’s psychology, it’s a lot of psychiatry—it’s knowing the person you’re dealing with, and the sensitivities of the two of you. Some writers can’t collaborate—they are at each other’s throats all the time, hostile to one another because of that constant rejection that has to go on in your day-to-day work. Writing and creating is nothing more than a series of those rejections, or, rather, criticisms. And the man who knows that, the good writer, always feels that criticism is valid.

“As far as lyric-writing is concerned, I’ve always found that my fellow workers agree it’s terribly hard. Nerve-racking, brain-racking. Oh, it’s easy if you want to rush out crummy verse, such as the stuff they’re writing today. I could do ten of those a day—one an hour. But I couldn’t do something for a show or a film in less than two weeks. When you’re rhyming, and looking for imagery, those lines don’t come easy. They take a lot of digging. Harold will write a tune, and it may go all over the place musically, and then you’ve got to fit that tune.8 Very touchy work. As I said before, I doubt if it’ll ever be able to say ‘I love you’ head-on. It’s my curved thinking, I guess.

“Nowadays a kid gets a guitar, he goes out and he knows he can make it. Three chords and one sentence repeated over and over again, and there you are. What’s terrible is that the broadcasters put out nothing but that stuff. No more Rodgers, no more Gershwin, no more Arlen or Kern. I try to listen, and I think most of what I hear is written very naïvely and crudely, without real form, real taste. Of course, here and there you see glimmers of some kind of really good talent, but it’s usually lost in the noise and the raucousness. I can’t distinguish one song from another.

“The really good fellows don’t have much of a chance these days. The businessmen get hold of record companies, they hire a bunch of kids to form bands, they get the records out of them, and they blanket the radio with sheer volume. Music today is money, that’s all. It’s rhythm, it’s hypnosis, it’s a good deal of hysteria and a lot of complaint. The words spell out the terror of the age in which the young are growing up. If you want to look at it as a social phenomenon, fine. It is. It belongs to today, but it won’t belong to tomorrow. Good music and good lyrics should belong to all time.

“I think my generation grew up with an entirely different attitude. The world had its problems then, and just as many drab and terrible things, too—but there was a certain hope. A dream. A goal. Measurements of grace that we all looked up to and had ambitions someday to reach. Everybody, every immigrant family that came to this country, was aware of education, aware of getting somewhere, moving forward. I was aware. I knew what my father was going through in his sweatshop down there on the Lower East Side. I always had the hope that someday he would be liberated from that. That was part of my whole chemistry, my nervous system. To get somewhere, to move forward…. Whereas today the emphasis seems to be all on escape: ‘It’s a rotten world, get away from it, the hell with it!’

“We’ve reached an era of abundance, I guess. Ours was an era of scarcity, and we had our eyes set on satisfying some of our hungers. But when you reach an era like this one, with abundance everywhere—and when that abundance isn’t distributed properly, so that only a few grab it and so many are left in poverty and in slums—then the immorality of the situation shows.

“But I’ve always been aware of the idiocy of the whole establishment and the system. That’s what titillated me into using satire. I’ve always thought that the way to educate, to teach, the way to live without being miserable, even though you’re surrounded by misery, was to laugh at the things that made you miserable. For me, satire has become a weapon … the way Swift used it in his prose, Gilbert in his verse, Shaw in his drama. I am stirred, and my juices start flowing more when I can tackle a problem that has profundity, depth, and real danger … by destroying it with laughter.”