“HE ALWAYS could write songs,” says his good friend and coworker, genial Abe Burrows. “They burst out of him! How, or why, or where? I don’t know how you can ask that. What makes any artist, even a Van Gogh or whoever? When he first was writing lyrics with Hoagy Carmichael, like ‘Two Sleepy People’ or ‘Small Fry,’ he had some fascinating things. And all the way along from there, the stuff was pouring out of him. It was always there. He read a lot, he asked questions a lot, he knew a lot. He was fascinated with words, the way I am. He lived with dictionaries. Not rhyming dictionaries. A terribly literate guy. Loved words—and loved to toy with them. And he used to work very hard. Always.”

Burrows stares out of the window of his New York apartment. “I think,” he says finally, “I’ve been a very lucky guy. Had the good luck to work with the two best lyric-writers of all time. Frank and Cole Porter. So I’m spoiled.

“Frank was always an intricate guy. Before he ever did a Broadway show, we were friends, and he used to help me. When I wrote a lot of my parodies, I didn’t care where it was, I’d play ’em any time. Out in Hollywood, lots of times we were at a party and I’d be loaded. One night I adlibbed ‘The Girl with the Three Blue Eyes,’ completely as it is. First time Frank and I met, I was doing it and another song of mine, ‘I Am Strolling Down Memory Lane Without a Single Thing to Remember.’ There I was, ribbing his whole profession. Next morning I had completely forgotten what I’d sung. I see Frank a couple of days later—he hands me a piece of paper with all my lyrics written down for me. That’s how he’d responded. That’s the kind of a guy he was.”

It was on the night of January 22, 1936, that there opened on Broadway a revue called The Illustrators’ Show. Its subsequent run was brief; in a matter of days the show folded and its scenery was carried off to Cain’s Warehouse, the Potter’s Field of flop shows. The world of show business would little note nor long remember that flop, but it must be considered a historic event. In its score was a song called “A Waltz Was Born in Vienna,” written by Frederick Loewe (who was later to write My Fair Lady with Alan Jay Lerner), and also, the first professionally performed lyric by Frank Loesser. In collaboration with Irving Actman, young Loesser, aged twenty-six, contributed to the proceedings the words to a number called “Bang— the Bell Rang!”

Such is the humble beginning of Loesser’s remarkable career as a professional songwriter, one that ended, shockingly too soon, when he succumbed to lung cancer in 1969.

Measured quantitatively against the large output of some of his more prolific contemporaries, the volume of what he left behind is, alas, small. But applying the yardsticks of quality, of execution, of brilliance of idea, and it’s an entirely different horse race. In that sweepstakes Loesser moves ahead of the field and stays there. In the argot of the Broadway types he so deftly portrayed in Guys and Dolls, Loesser has class, he has style, he has that extra-special something that is blue-ribbon all the way.

In all his prolific years of writing lyrics for Hollywood films from 1937 on, Loesser always had a clear idea of where he was headed. “From that first day he was signed up at Paramount, Frank was going,” says Burton Lane, who did many songs with Loesser there. “He kept on saying to me, ‘Why should Irving Berlin be the only guy who owns his own publishing house—and writes all his own songs?’”

After his World War II hitch in the Army, during which he wrote both words and music for “The Ballad of Rodger Young” and “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition,” Loesser came back to New York in 1948 to work on Where’s Charley? for Ray Bolger. “You know,” says Jule Styne with deep affection for an old friend and collaborator, “here’s a fellow with hardly any musical education, and he took it on and wrote some marvelous songs. But he had a right to write his own music. Certain fellows, who shall be nameless, haven’t. But Loesser had; he could write his own music. He told me, ‘Listen, after I write with you and Arthur Schwartz and Hoagy Carmichael, and this one and that one, by God, I have got to learn something, if I’m smart. You boys showed me how it goes.’”

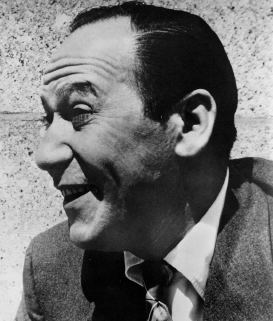

Frank Loesser

And it went. After Where’s Charley? there followed Guys and Dolls in 1950; The Most Happy Fella, for which he wrote his own libretto, adapted from Sidney Howard’s play They Knew What They Wanted, in 1956; and Greenwillow in 1960. His last hit show was the brilliant How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. All of them have musical scores which must be considered permanent eighteen-karat jewels in the American treasury.

And Loesser also achieved the second goal he had mentioned to Burton Lane back in the early Paramount days. He set up his own publishing house, Frank Music, not only to publish his own works but also to nurture and develop the talents of others. His discovery of the tyro talents Richard Adler and the late Jerry Ross led to his sending them over to George Abbott. When the two young men wrote The Pajama Game and Damn Yankees, their work was published by Frank Music. Loesser, with his business acumen, might well fit Alexander Woollcott’s description of his friend Harpo Marx: “A genius … with a fine sense of double-entry bookkeeping.”

Even though he was the son of a classical music teacher, and the younger brother of Arthur Loesser, a highly accomplished pianist and major music critic, he never formally studied music. “I didn’t have the patience to concentrate,” he was to say later. He had attended Townsend Harris High School in Manhattan (an early incubator for high-IQ’d youth), but he dropped out of City College in his teens—“I wasn’t in the mood to learn.”

There followed a series of dead-end pursuits, assorted jobs which led nowhere. At eighteen he served a brief stint as city editor for a New Rochelle, N.Y., newspaper. According to his brother Arthur, he first displayed his talent as a lyricist one night when he was assigned to cover a Lions Club dinner. “He obliged an officer by supplying couplets celebrating the exploits of all the club members. Such lines as ‘Secretary Albert Vincent, Read the minutes—right this instant,’ got him started on his eventual career with words.”

On his days off, Loesser wrote acts for various performers on the Keith vaudeville circuit. “Somehow you had to find a way of getting a job,” he was to remark years later. “The Depression was here, and I even got one job checking the food and service in a string of restaurants. I was paid seventy-five cents each to eat eight or ten meals a day. At least I was eating, which a lot of people weren’t. You had to keep alert all the time. I suppose that’s where this tremendous energy of mine originated.”

Loesser’s first published song was written in 1931, in collaboration with William Schuman, who is now president emeritus of Juilliard and of Lincoln Center. It was called “In Love With a Memory of You.” “I gave Frank his first flop,” says Schuman, “and, really, the only song flop he ever had. You can’t be condescending about musical genius. He was one of the greatest songwriters the United States ever produced.”

It’s almost impossible to find somebody who’ll take the negative side of that debate—if it can be considered one. Even such a stern critic as Stephen Sondheim is on record as saying, several years back, “Any man who has the nerve to set the line ‘Some irresponsible dress manufacturer’ the way Frank did in How to Succeed deserves a medal.”

Loesser and Actman were brought to Hollywood in 1936, but their stay at Universal Studios was brief. Soon the young lyricist was again job-hunting. But now he was unemployed in Hollywood; in that town, such status is akin to that of an Untouchable in far-off India.

“I had been in Hollywood about a year, and had an option coming up on my contract,” says Burton Lane. “My agent brought two young writers around. One wrote music; the other was Frank Loesser, who did lyrics. I looked at his things; they were just great. Superb. I went to the front office at Paramount and told them I’d flipped. I called Frank, told him to go right down and they’d listen to him. A guy named Lew Gensler was head of the music department then, a former songwriter himself. He flipped over the stuff, too. While they were making their corporate mind up whether to sign him on, I had a call from Frank. He wanted to know what I was doing. Could I come over, he wanted to show me some of his work that I hadn’t heard. He lived on Sunset Boulevard. I had to walk about two hundred steps down from the street to get to his little apartment.

“I’d been there about five or ten minutes when Lynn, his first wife, asked me if I’d like to have dinner with them. I said no, I’d already eaten. She opened a can of beans—one can for both of them—and an apple, which she sliced for their dessert. They were absolutely broke.

“Anyway, Paramount came through with the contract. A ten-week deal for starters. So I told Frank he could use my office any time. I came in the day after he’d signed, and I’ll never forget this—there was one guy measuring him for shirts and shorts, another guy measuring him for suits—the works! The day after he’d signed that contract, everything was going to be made to order!”

Loesser and Lane shortly thereafter turned out their first hit song; it was one which Bob Hope and Shirley Ross were to perform in a Paramount B-picture musical comedy, and it was called “The Lady’s in Love with You.”

“From then on, we were assigned to everything,” says Lane. He himself was not to return to Paramount until three decades later, as the composer of the Broadway hit show On a Clear Day You Can See Forever. But today he winces at the recollection. “I did one picture with Frank—it is the most embarrassing thing, it’s shown on TV all the time. I wish they’d burn the goddam negative! Spawn of the North, with George Raft—we wrote everything in it. I don’t remember the titles—I must be subconsciously blocking them out. Oh yes, one of them was ‘I Like Hump-Backed Salmon.’ I didn’t even know what a hump-backed salmon was! Maybe Frank made it up.

“He was a very difficult guy even then. Very secretive. He’d sit across the room from me, and I’d say, ‘Well, what are you thinking about?’ He wouldn’t tell me. He’d keep it to himself. And then I’d see him smile. I’d say, ‘All right, Frank, what is it? Don’t keep it to yourself; let me know the goodies, too!’ And suddenly he’d jump up, and he had it all written out, a complete lyric. I’d put it on my piano, and he’d want me to sing it right away. Hell, I hadn’t even seen the lyric yet! And if I’d stumble, he’d yell. ‘God damn it, can’t you read?’ Here I was, trying to think of what I’m doing, and reading his handwriting, which was terrible, and I’ve never seen the lyric before, and he’s yelling at me!

“An amazing guy,” muses Lane. “Another time one of the B-picture producers picked one of Frank’s lyrics and called me in and asked me to set it to a tune. ‘We like this lyric, but we gotta have it set by this afternoon.’ That’s how they worked—always pressure. I said, ‘Okay, if you need it that badly, it can’t be so important. I’ll just knock something out for it.’ Went back to my office, and I guess it took me five minutes to write that melody. The title of what Frank had written was ‘Says My Heart,’ ‘Fall in love, fall in love, says my heart.’ Lovely lyric, bright idea. Five minutes was all it took— big hit! Oh, he was a fantastic talent.”

Loesser was already demonstrating his remarkable versatility with the éclat of a seasoned pro who’d been at it for years. When Dorothy Lamour crooned “The Moon of Manakoora” in The Hurricane, it was a Loesser lyric; Bob Hope and Shirley Ross introduced “Two Sleepy People”; and Bing Crosby made a hit out of his “Small Fry.” These last two hits were done with Hoagy Carmichael. Working with Frederick Hollander, a diminutive German who had written songs for Marlene Dietrich in their homeland and had followed the lady to Hollywood, Loesser turned out a score for Destry Rides Again, including the durable “See What the Boys in the Back Room Will Have.”

At the behest of composer Jule Styne, who had signed on as a fieldhand at Republic Pictures, a deal was arranged whereby Paramount loaned Loesser to Republic for a low-budget Judy Canova musical. Cy Feuer—who with Ernie Martin was to be responsible, ten years later, for bringing Loesser to New York to write Where’s Charley?—was at that time the head of the music department at the tiny Republic studio.

“Oh, when Frank heard about being loaned out to Republic, he blew up. He had a powerful temper, anyway. He’s the only guy I ever saw who would make his point by jumping with both feet off the ground! While yelling,” grins Feuer.

“He came to me and he said, ‘How can you do this to me? Here I am, just working my way up, I’m getting to work with some really good composers—and you pull me back into this thing!’ And I had to schmeichel [sweet-talk] him and talk him into doing it. He had to do the job—it was part of his contract—but he didn’t like the idea one bit. Finally he came over, and he went to work with Jule, and they gave us a hell of a good score for Sis Hopkins.1 Their songs were fine, the lyrics bright and clever. Something very special for a place like Republic, believe me. By the time it was done, Frank was very pleased with the job; he went back to Paramount and arranged to borrow Jule—from Republic! There they did a picture called Sweater Girl. They had two songs that were hits right out of the box. One of them was ‘The Liberty Magazine Song’—‘I Said Yes, She Said No’—a big novelty. And the second was a big ballad called ‘I Don’t Want to Walk Without You, Baby!’

“That’s where Frank demonstrated his marvelous instinct for picking out tunes,” says Feuer, a cheerful, energetic man whose latest success is the musical film Cabaret. “When Jule played Frank that tune, it had another lyric, but Frank insisted that they buy out the other lyricist. ‘I can make a hit out of that tune with another lyric,’ he told Jule. And he was absolutely right!”

The songs that Loesser wrote in those pre-World War II Hollywood years are remarkable for their strength. The ordinary idea, the shortcut, the triumph of technique to cover the absence of an idea—none of that for Loesser. He was on the prowl for a brighter notion, a stronger line. Certainly he could turn out an “I’ve Got Spurs that Jingle, Jangle, Jingle”—that was part of the job. For Betty Hutton he could write dynamite material— “Poppa, Don’t Preach to Me” and “He Says Murder, He Says.” And he was already coming up with such gems as “I’d Like to Get You on a Slow Boat to China.”

But listen to his ballads—the haunting “Sand in My Shoes” (which he did with the late Victor Schertzinger) or “Spring Will Be a Little Late This Year,” “Let’s Get Lost,” “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So,” or “What Are You Doing New Year’s Eve?” They reveal the deep strain of romanticism that underpinned his later work.

“He really worked from his gut,” says Abe Burrows. “He was an incurable romantic. Once, in giving me a big compliment, Frank looked at me when I came up with some ideas, and he says, ‘You got so much talent. Why can’t you save it for romance? Why do you waste it on comedy?’ ‘Cause he himself knew he could write the big comedy songs, but what he wanted was to reach the audience, get into them.”

With Arthur Schwartz, Loesser did the lyrics for Thank Your Lucky Stars at Warner Brothers, which treated audiences to Miss Bette Davis chanting his wry “They’re Either Too Young or Too Old”—and then his draft board sent him greetings. Shortly thereafter he became Private Frank Loesser, part of a Special Services unit.

“You should’ve seen him!” chuckles Burrows. “He was proud of being in the Army, but he insisted on having his private’s uniform tailored! He was the sharpest buck private you ever saw—he had a uniform that a general would have given his four stars for! And he really hit his stride in the Army. That’s when he started writing his own music.”

The first of Loesser’s solo jobs was to become an enormous wartime success; based on the exploits of a heroic service chaplain, it was the rousing “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition.”

During his Army years the talented private became a powerful oneman propaganda weapon. He turned out dozens’ of songs for service shows; “First Class Private Mary Brown” for recruiting WACs; and another wartime smash hit, “The Ballad of Rodger Young.” For the foot-soldier he did “What Do You Do in the Infantry? You March, You March, You March!”

“He always excited me,” says Cy Feuer. “His turn of mind would always have a sort of a curve. And the way he used to sit and pick at the piano, and these inventive things that would come out musically, that fascinated me too.”

By this time the war had ended and Loesser, Feuer, and Ernie Martin were all back in civilian clothes. Feuer and Martin, with no previous experience at producing on Broadway, were struggling to make a musical-comedy version of Brandon Thomas’s classic Charley’s Aunt. (The two producers now share an executive office, and there are times when their enthusiastic conversation overlaps.)

“It was tough going,” says Feuer. “But I was so sold on Frank. I got hold of Ernie one day and I said, ‘Look, we’ve got to go with Frank!’ Which Ernie agreed to. So we originally planned on having Frank team up with Harold Arlen. Fine. But something came up and Arlen had to bow out—a problem in his schedule. And there was Frank without a composer. So Frank said, ‘Why don’t I do it myself?’ We were enthusiastic, but then we had to sell him to the Bolgers. [Bolger was the prospective star of the show.] Not easy, because who the hell was Frank? What had he written? He had some good lyric credits, sure, but, frankly, not much music. Well, finally the Bolgers agreed; they were fascinated with Frank himself, who was kind of fun— socially, he was a real charmer—and they agreed to take a chance on him.”

Ernie Martin adds, “At the beginning, Rodgers and Hammerstein were instrumental in getting the thing off the ground. See, we’d never raised any money for a show before—who the hell were we?—and we were struggling. But they knew Frank’s work, and when we brought over the stuff he was writing, Dick and Oscar bought two units in the show as an investment. They had absolute faith in Frank; and they also said we could tell people that they’d become backers—which was a hell of a big boost, believe me. And of course Frank went ahead and did a fantastic score. I think what he wrote for Charley is one of his outstanding things even now.”

Where’s Charley? is endowed with the lovely ballad “My Darling, My Darling” and a raft of other brilliant songs—“Make a Miracle,” “The New Ashmolean Marching Society,” and the rollicking “Once in Love with Amy,” the show-stopper which Ray Bolger sang and danced, enchanting Broadway audiences.

‘Everything new, everything a fresh concept, musically and lyrically,” says Feuer. “He was just a natural show-writer. As a matter of fact, Frank never came to life fully until that show. It was his natural medium!”

Martin picks up. “It didn’t make much of a splash at the beginning, we didn’t get great notices at all. But there were telegrams from all the other composers—Rodgers, Hammerstein, Cole Porter—congratulating him on his brilliant work. Cole was always so starry-eyed about other people’s work. With Loesser, he used to sit there and say, ‘How can he have thought of a thing like that?’

“After a while, while we were still limping along, Arthur Schwartz wrote a piece in the New York Times Sunday section saying that Frank was the greatest undiscovered composer in America. Wrote it completely on his own, spontaneously. It was quoted. Then people started to pay attention to what was in that show. But that’s the sort of thing other composers felt about Frank.”

“Everything he did was totally fresh,” enthuses Feuer, “even the things we had to cut out of the show. I remember one delightful thing he’d written—it was called ‘Strolling in the Park.’ For Jack’s father, who was this elegant gent but didn’t have a nickel. It’s written like an English hunting song, with two French horns carrying the tune—two down-and-outers.

“Oh, Frank was a unique fellow,” Feuer states with obvious feeling. “A great companion for fellows. Never drove a car. Didn’t know how to drive. Never learned how.”

Martin tunes in. “Strictly a city boy. Loved to quote Nunnally Johnson, who said that if he had a place with green grass, he’d pave it.”

Feuer chuckles. “Once he said to me, ‘Cy, there’s something about the country—working there—it’s very bad. There’s something about the chlorophyll that keeps me from writing!’”

“He had strange work habits, you know,” continues Martin. “He’d get u at four thirty or five A.M., have a martini, and go to work between five and eight in the morning. He wasn’t a boozer, he merely oiled himself up. Then, after he wrote, he’d go to sleep, get up later, work some more. Napped again during the day, for maybe three or four hours. He knew that I was an early riser; sometimes he’d call me up on the telephone in the morning, six A.M., and the voice would say, ‘Are you up?’ and I’d say, ‘Yeah.’ And he’d start to whistle something he’d just written—on the phone!”

“Frank never stopped thinking about his things,” says Feuer. “How to improve them—always working to make them better.”

“But,” interrupts Martin, “paranoid about people. Wouldn’t sit in a restaurant unless his back was to the wall. I never knew what that was all about. Hated to make commitments. He’d make a date to go out to dinner. ‘Okay, Frank, when?’ Two weeks from next Tuesday. He’s say, ‘Call me next week.’ Call him next week—‘How about it?’ He’d say, ‘Check in next Tuesday.’ Tuesday you call—‘What time?’ ‘Oh, call me at four this afternoon.’ In other words, he was unable to make a definite commitment. Several of our shows, he didn’t agree to do them until after they got on the stage! He never said, ‘Okay, I’ll write Guys and Dolls.’ Never. One day he hands us four songs, and now we knew he was doing it!”

“Do you realize we never signed an actual contract with him until after the show was playing on Broadway?” exclaims Feuer.

“There’s something else about Guys and Dolls—it shows how brilliant Frank’s instincts were,” says Martin. “The first book that we had done, by Jo Swerling, wasn’t right. We wrestled with it for weeks, but it didn’t capture the Runyon quality at all. So we finally brought in Abe Burrows to rewrite it, based on a different concept and a new story line—the business of the wager, Sky betting all the horse-players their souls. But by this time Frank had written an entire score … to the original wrong book! Then Abe rewrote the book to suit Frank’s score, keeping all of Frank’s songs! In other words, Frank’s instincts on it were so right that Burrows actually fashioned the new book from song to song, created scenes about the songs that Frank had already written!”

“Frank came in with that wonderful trio, the ‘Fugue for Tinhorns,’” recalls Feuer. “We had no spot in the show for it. He said, ‘This feels right to me for this property.’ Three horse-players singing about the morning’s selections. But it had nothing to do with the plot, nothing to do with the book. So we had it, a great piece of material, and we’re struggling to find a spot for it. And then Ernie finally said, ‘If you’ve got no place to put it, why don’t you stick it up front, as a genre piece? Where it’s not about anything, but it opens the show and sets the whole thing going.’ Which is where it went, and did exactly what Frank thought it would do.”

(“When you’re dealing with songwriters,” says Abe Burrows, “I think you’re dealing with the most intuitive kind of guys. None of them can explain where the hell their stuff is coming from. They’re all a little nuts— and it comes out. See, everybody forgets that the purest example of abstract art in our world is music. Music gives you all of those things, love, hate, anger, fear, all of it in abstract form. So I had those songs of Frank’s to go by, but then we’d sit and we’d look hard for song spots. Some of them came out of the dialogue. And one day we were in Philly and we were stuck for a song, and I had a line of dialogue, ‘The oldest established permanent floating crap game in New York.’ And I said, ‘Gee, Frank, it lays out, like a lyric, you know?’ And I took that out, and Frank made a song from it.”)

“Tell him about the ice-cream cone,” says Martin, chuckling.

Feuer does. “Frank wrote ‘The Oldest Established Permanent Floating Crap Game’ over a weekend. And it was now going to be put into the show. Everybody was supposed to sing it. The people had learned the song. We were onstage, and Michael Kidd, the choreographer, was there, and we were ready to stage it. We hadn’t done a thing yet. We had the guys going through the number, and they’re mumbling. We were just fashioning the introduction—you know, where the music hits a chord, and it’s ‘There’s Hot Horse Harry—ba ba ba!—Big Red from Philadelphia—ba ba! And Mike says, ‘All right, fellas, just run through the number once, and we’ll try to pick who does which line,’ and so-and-so. And they start singing it for the first time. Suddenly, from the back of the empty theatre, down the aisle comes Loesser, and yells, ‘Hold it! Stop!’ And he is yelling, ‘That is the worst goddam thing I have ever heard!’—plus a lot of four-letter words, all about a bunch of guys who’ve never seen this number before!

“Everyone was terrified. Mike Kidd, who’s very level-headed, says, ‘Look, Frank, we’re just starting.’ And Frank says, ‘You shut up!’ And I said, ‘Frank, for Christ’s sake, we’re just getting started.’ And he says, ‘You’re Hitler!’ He said to me, ‘Hitler! And you’re working for me! I’m the author—you’re working for me!’ And the guys on the stage don’t know what’s happening, and he turns around and he says to the conductor, ‘Take it from the top! I want to hear the best goddam singing possible—I want to hear this full out!’

“The conductor says, ‘Okay, boys, from the top,’ and they’re all standing rigid on the stage, and they start to sing what they only learned yesterday. They bellow it out. Now they’re singing their hearts out! Really singing! And Frank backs up the aisle, they’re singing—and he’s headed out.”

Martin continues. “I could see he was going out of the theatre, so I followed him. He went into a little ice-cream store that used to be on the corner there, bought an ice-cream cone, took it, and he walked to his hotel, eating it.”

“You know what it was?” asks Feuer. “It was pay attention to the music, that’s all.”

(“It was because he worked so much from pure feeling,” says Burrows. “You see, Frank always thought of himself as conscious of everything he was doing, and completely in charge.”)

“What a temper,” muses Martin. “What about hitting Isobel Bigley in the schnozzle? She was doing this song he’d written called ‘I’ll Know.’ We’re rehearsing it. You know that lyric, ‘I’ll know when my love comes along’—nobody can really sing that; she always broke somewhere in the middle of that range. She could never do it, who the hell could? We’re rehearsing it, and again she breaks. Frank walks up and he gets up on the conductor’s podium—a little box they have there—and he hits her, boing! right smack on the nose! SO she starts to cry. Now he drops to his knees— he doesn’t realize what he’s done, but it’s done.”

“Yelling, ‘Forgive me!’” follows Feuer, doubled up with laughter.

“He sent her a bracelet that must have cost a thousand bucks,” says Martin. “Such apologies! Of course, from then on she had him buffaloed, because whatever she wanted was not good enough—she’d get it.”

“The only guy I ever saw punch a soprano in the nose.”

Martin: “Took a swing at me once, too! It was in his house in California. We were in the living room having an argument about some clause or other. His agent was sitting in the middle, between us. I don’t remember what it was about—something unreasonable Frank was insisting on. Not his billing. He used to say, ‘I don’t care about billing my name—leave it off! My songs are my billing!’ There we are, arguing and wrangling, and suddenly I say, ‘Fellas, look!’ There’s Frank’s agent—a little guy—and he’s fallen fast asleep on the sofa between us! I don’t know why, but Frank got sore at this, and he gets up to give me a belt across the coffee table. We’re both the same size, him standing and me sitting, and he really swung!”

“Missed Ernie, but went all the way around!” chuckles Feuer.

If Where’s Charley? had taken a few weeks to catch on with the audience, there wasn’t a moment’s hesitation about the success, in 1950, of Guys and Dolls. From the second the curtain rose on the three Runyon characters singing “I got the horse right here!” until the finale with the cast singing the title song, Loesser had the audience in his back pocket.

“Do you know what the great thing about him and his lyrics was?” asked Feuer. “Do you realize that he was the master of the one-syllable word? Look at that couplet—‘When a bum buys wine that a bum can’t afford, it’s a cinch that the bum—is under the thumb—of some little broad!’ All but three are actually one-syllable words. Who else would have been able to do that?”

Guys and Dolls is generally conceded to be one of the four or five best American musical comedies. That chancey word “classic” can safely be applied to the saga of Sky Masterson, Nathan Detroit, Miss Adelaide, and all the rest. Burrows’ libretto melds perfectly with Loesser’s songs. (“He worked so intuitively,” says Burrows. “He would say to me, ‘For the next three or four minutes the stage should be filled with a big choral sound.’ He didn’t know why, he just felt it. Then he’d make it happen.”)

Every one of Loesser’s songs was a happening. The chorus girls and Miss Adelaide doing “A Bushel and a Peck” and “Take Back Your Mink,” the rousing “Sit Down, You’re Rocking the Boat,” the duet “Sue Me,” the brilliant lyrics to “Miss Adelaide’s Lament.”

The female remaining single, just in the legal sense,

Shows a neurotic tendency—see note.

[Look at note]

Chronic, organic syndromes—toxic or hypertense

Involving the eye, the ear, the nose and the throat.

In other words, just from wondering whether

The wedding is on or off,

A person … can develop a cough.

As Loesser himself put it, his songs are his billing. But it was always the ballads—“I’ll Know,” “I’ve Never Been in Love Before,” “If I Were a Bell”— that were his special pride and joy.

“I remember,” says Feuer, “he always used to say to Abe—this was when he’d be jumping up and down with both feet to make the point— ‘I’m-in-the-romance business!’ And he was always frustrated by the fact that so many of the actors we used couldn’t sing. I mean, take Sam Levene, our Nathan Detroit. You have no idea what a problem it was to get him to come in on the same note each night. He was tone deaf. Night after night, it was anybody’s guess where he’d hit the cue note on ‘Sue Me!’ And since Frank had a good voice himself and he could sing well—maybe that’s why he’d get so angry when the actors would sing the songs differently from what he heard.

“We once had a hell of a fight with Frank about his ballads in the second act of Guys and Dolls. George S. Kaufman, our director, was with us, and he kind of acted as a mediator. Frank was saying to me, ‘When are we going to have a reprise?’ He wanted the ballads plugged in the second act. I told him we weren’t going to do that arbitrarily; it would spoil the flow of our show. He’s yelling about how every composer gets to reprise his ballads—that’s what makes them into hits. I’m telling him I don’t care if it’s customary, it’s wrong for this show. ‘Where are they going to hear my songs?’ he yells. ‘What the hell do you think I’m in this for?’ We went on arguing like that, and then finally George Kaufman said, ‘Wait a minute, fellas. I’ll tell you what. Frank, I’ll agree to reprise your ballads in the second act—if you allow us to reprise some of the first-act jokes in the second act!’”

For the next three years Loesser worked by himself on a project based on Sidney Howard’s hit play They Knew What They Wanted. “This time he wanted to try it all himself, as a kind of exercise,” Burrows remarks. “This was the one he really got his gun off with—he was proud of it. He had a right—it was a helluva show.”

This time Loesser would not only write music and lyrics on a grand scale but he would do his own libretto. Howard’s play was set in the Napa Valley and dealt with the bitter-sweet love story of a prosperous Italian-American grape grower who takes himself a mail-order bride. Loesser told an interviewer, with his customary directness, “I figured, take out all this political talk, the labor talk, and the religious talk. Get rid of all that stuff, and you have a good love story.”

When he had completed his version and called it The Most Happy Fella, the work fell between two stools—somewhere between a grand-scale musical and a minor-scale grand opera. Contrary to established Broadway custom, the program for The Most Happy Fella did not list the individual songs Loesser had written; and he insisted that his work be billed as “A Musical.”

Burrows went down to Philadelphia for the première performance. “Frank asked me to come down and take a look,” he wrote in the New York Times after Loesser’s death. “This time he was flying solo. Music, lyrics, libretto. Pretty nervous about it, too. And so was I, for him. The show was remarkable. New kind of musical? Opera? Whatever it was, it was something special.”

To perform his music as he wished it to sound, Loesser had cast as his lead an ex-Metropolitan Opera baritone, the late Robert Weede. The part of his mail-order bride was played and sung by lovely Jo Sullivan.2 The new show was filled with more than thirty separate musical numbers—choral passages, arias, duets, trios, quartets. There are, indeed, so many and varied pieces of complex music in his score that it must be described with one of his own titles, “Abbondanza!”—abundance.

“I came out of the theatre in great excitement, dashed up to Frank, and began chattering away about the marvelous funny stuff,” continues Burrows. “All those songs like ‘Standing on the Corner, Watching All the Girls Go By,’ ‘Big D!’ Suddenly, he cut me off angrily. ‘The hell with those! We know I can do that sort of stuff! Tell me where I made you cry!’ Always searching. He went out and tried something different the next time, too.”

Loesser’s next venture was an adaptation of B. J. Chute’s gentle novel Greenwillow, a delicate fantasy set in a totally imaginary bucolic world. In that show the Loesser propensity for romantic balladry was given wide range. His “Never Will I Marry” is an as yet undiscovered treasure; so are “Summertime Love” and “Walking Away Whistling.”

But the show was not to repeat the huge success of his three previous works. Perhaps the words of one critic, Walter Kerr, help to explain its failure. “Folklore may just be the one dish that can’t be cooked to order.”

“A very complicated guy,” comments Martin. “He’d begun to concentrate on building up his own publishing house. By then he’d married Jo Sullivan and they had a daughter; she was about five. You know, if you haven’t gathered it already, Frank was a damned good businessman, and his firm was flourishing. Once we were out in California with him and he was telling us how he was going to leave behind this great estate. Copyrights, copyrights, that’s all he could talk about. And we said, ‘Yeah, you know who’s going to get it all, Frank? Susie’s going to marry some pimple-faced little guy whom you’re going to hate! And he’s going to be the guy who’ll wind up with all your dough!’ Well, he took care of that as soon as possible, believe me, because the next child they had was a boy!”

“Do you realize that Frank was an expert cabinetmaker?” asks Feuer. “He had a basement workshop in his house, fitted out with all sorts of tools, and he could turn out some of the most beautiful, complicated furniture you ever saw.”

“But always a New York kind of guy. Street boy,” says Martin. “In California he had this house with a tennis court—the net was always down. He never went outdoors. One day he said to me, ‘Let’s go sit in the sun.’ Which in itself was a remarkable thing. I said, ‘Okay,’ and he said, ‘Wait a minute.’ He went upstairs and he came down again in a little pair of blue swimming pants. And he had left on his garters and his socks and his shoes. We went out there and we sat in the sun for about five minutes, and that was enough! But later on he became more of a family man and he did a lot of cute things. Bought a house out in Westhampton, near us. One day he arrived at my house. He had bought a boat which was a raft kind of thing with an awning; and he had a little orchestra kind of thing. He and the kids were all playing. And he came sailing up like a Southern riverboat captain. Little jokes like that…. We gave a Fourth of July party once, and Frank came dressed like Uncle Sam—in a red, white, and blue outfit! … And then he got interested in bird-watching. He loved gadgets. He built a oneway mirror into a window—had birdhouses outside, and he’d sit there watching: ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute; there’s a Baltimore Oriole!’”

The winning combination of Burrows, Loesser, and Feuer and Martin reunited in 1962 to produce another smash success, How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. Once again the dimension of Loesser’s virtuosity remains dazzling. The cutting edge of Burrows’ satire, working together with the score, does a masterful job of puncturing more of our most precious American shibboleths about the Horatio Alger world-of-commerce success story. But, as always, it wasn’t the comedy numbers that Loesser looked for; he was digging down for romance.

“Before I wrote a line of libretto,” says Burrows, “we had figured out eight song spots, and then we’d kick it around. Then he came in with the ballad ‘I Believe in You.’ And I said, ‘Frank, it would be great if the guy sings it to himself—in the mirror.’ And I figured he’d hit me that time! Thank God, it stayed a love song, which it was. But that was how we worked; it was kind of a back-and-forth that grew between us.”

Out of that back-and-forth were to come such brilliant musical-comedy numbers as “Dear Old Ivy,” “The Company Way,” and the rousing choral hymn to American mediocrity, “The Brotherhood of Man.”

“When it came to ‘A Secretary Is Not a Toy,’ Frank said we could never make it work,” recalls Feuer. “It was written for Rudy Vallee to sing. Vallee wanted to sing it in another tempo, and he was rehearsing, and finally Frank got sore and we had another one of those big blow-ups! I got them into the office and I tried to reason it out with both of them. I told Rudy that Frank had written this score, that he had it in his head the way it should be done, and that Rudy should respect that and do the song the way Frank had conceived it. Well, Rudy said, ‘You don’t understand. I’m an interpreter of songs.’ And he starts giving me a list of all his hits, the songs he’s helped make in his time. And while he’s talking, I see Frank is ready to hurl himself at Rudy’s throat! So I kept hold of Frank—I wasn’t trying to arbitrate this, but to let off all the steam and get everything back on the tracks. Frank is now yelling, and I’m saying to him, ‘Take it easy, Frank.’ And I’m telling Rudy, ‘Frank must have his way with every goddam piece of material he’s written for this show—that’s fundamental, and that’s the way it’s going to be!’ And we all left the office. Frank went and put on his coat and hat and quit the show. Left.

“We called for him, and when we reached his house, we get the word that Frank says he’s finished, he’s not coming back, he’s out of it—we can go ahead any way we want. I asked to speak to him, and they said, ‘He won’t speak to you.’

“Then I receive a telegram, two pages long, in which he said he was deeply disappointed in me, I’d let him down, I’d finked out on the whole thing, and he went on, after all the years that we’ve known each other, and the friendship, and everything. You know what Frank wanted me to do? I hadn’t punched Rudy Vallee in the nose—and I’d also prevented him from punching Rudy in the nose! Even though I’d told Vallee that he’d have to do it Frank’s way, Frank wouldn’t buy that. He wanted the guy floored for saying his piece!

“So I sent back a wire ignoring his wire. What the hell am I going to answer? That I’m sorry I didn’t punch Rudy? Sent the wire and I prevailed on him to return. And back he came—smiling, sort of sheepishly, and went back to work.”

“It was another ice-cream-cone-incident, just like in Philly,” observes Martin. “Frank used to burst. It was kind of like a volcano.”

Martin pauses for a moment and chuckles, then nudges Feuer. “Remember that night in England?”

“Sure! We could talk about Frank for eleven years!” says Feuer.

“He never stopped thinking about things!” Martin continues. “We were opening Guys and Dolls in England, in Bristol. We’re in this dreadful little English hotel, and Frank and I are sharing the room; we’d registered at night, so we hadn’t seen where the hotel was located. About three in the morning we hear a terrific WHOO!—one of those big ship whistles—and the whole hotel shook! We wake up, run to the window, pull up the blind— and there’s a porthole outside! A ship! The damned hotel is sitting by the side of some canal!

“So I finally get back to sleep again, and about an hour later Frank is shaking my shoulder. He can’t sleep any more. He’s up and in his bathrobe, and he’s been pacing around the room. I see cigarettes everywhere—you know, he was a chain-smoker. He doesn’t want me to be asleep because now he has something on his mind. He says, ‘Listen, we can open it in Detroit!’ And he starts ad-libbing to me a whole black version of Guys and Dolls! We should do the thing with a cast of blacks. Four in the morning, and he’s already up and away with a whole new goddam concept!”

“Oh, the cigarettes,” says Feuer sadly. “You know, Frank literally smoked himself to death. Jo, his wife, was always after him to give it up. When we went down to Philly with How to Succeed, he would rent a piano and put it in the suite—a small baby grand for him to work on. And he was having cigarettes smuggled in. He’d say, ‘Bring me a pack of Camels, but don’t let Jo see.’ Three packs a day. With cigarettes Frank was like a junkie or an alkie.

“Calls me one day. I should come down to the suite. I go down. ‘You won’t believe this!’ he tells me. ‘What are the odds against this?’ He points at the piano, and the piano is all white, covered with white dust. ‘Look!’ he says. ‘Look!’ A piece of the ceiling above the piano has broken, and dust has fallen down all over the piano. ‘What are the odds against this?’ he yells. ‘In this whole fucking hotel—look what happened!’ He lifts up the piano lid. ‘Jo comes in,’ he says, ‘cleans off the piano—and finds my carton of Camels inside the piano!’”

“His work on How to Succeed was brilliant, musically and lyrically,” says Burrows, up in his Central Park West apartment as the dusk is falling. “A tough, abrasive score. The satire was savage and funny. He and I got a Pulitzer Prize for that one. But a week later, when we met at lunch to search out a new project, he was once more hunting for romance and tears. I respected him for that. That big talent had to be respected.

“You know, Frank was always after me to write songs. We’d done one once—on the old Duffy’s Tavern radio show. It was called ‘Leave Us Face It, We’re in Love.’ Shirley Booth sang it.

“We had a tremendous feeling for each other. Though he was only about six months older than I, he always treated me like an older brother. We fit together, kind of. We talked the same way, you know. Matter of fact, when we did Guys and Dolls, it was strange—Cy Feuer and I went to the same high school, so did Mike Kidd, and Frank had grown up in the same way we had. We all talked the same language, even.

“So different from Cole Porter. See, Cole I was also close to, but in a different way. A very serious musician, worked like a dog. I remember lots of times seeing Cole at three in the morning, working on a song. But you know how Billy Rose described Cole—he said he was a ‘toff.’ The last of the great toffs. Cole always had that terrible physical pain—suffered like hell—but he’s the only guy I ever worked with who opening night would come to the show. I mean, he’d sit down there. Come right down the aisle, take a seat in about the fifth row, and sit and enjoy it hugely. ‘Beautiful!’ he would say. ‘Lovely!’ Liked everything. The rest of us all sick from nervousness. Not Cole. I know Cole would have moments when he’d get disgusted, but I don’t think he ever had the agony of spirit that Loesser had—that constant striving … and extension … and dissatisfaction.

“See, Frank always minded that his really big songs were ‘Two Sleepy People’ or ‘Standing on the Corner,’ comedy stuff like ‘Miss Adelaide’s Lament.’ Remember his ‘Baby, It’s Cold Outside’? An absolutely brilliant piece of comedy material. I always was sore at him for selling it to Metro for an Esther Williams picture. That thing was much too good for where it went—it belonged in a picture. That thing was much too good for where it went—it belonged in a Broadway show! But what Frank wanted was the hits to be his romantic songs.

“That’s what I mean when I say we were so alike in our approach. We always saw that curve. You know, when I go out on lectures, people always stand up afterwards when they ask questions, and the first question is always, ‘Mr. Burrows, haven’t you ever wanted to write something serious?’

“And I always answer the same. I say, ‘But everything I do is serious. It just comes out funny.’ Which is true. And Frank was the same way.” Burrows stares out the window as the lights begin to come on through Central Park. “That’s about all I can say.”

“I visited Frank the day before he died, up at the hospital,” says Martin softly. “I knew Frank was dying—he was sitting cross-legged on the bed with just his pajama bottoms on, looking like a cadaver. There was this breathing-machine going next to him … and Frank was smoking a cigarette.”

“Abe loved him very much,” says Cy Feuer. “All of us did. In fact, I must tell you, when Frank died I couldn’t get used to the idea that he wasn’t there any more.”

The office is silent, the only sounds are the traffic moving past on Park Avenue.

“I couldn’t either,” says Ernie Martin. “I still can’t.”