IN THE last decades of the eighteenth and early decades of the nineteenth century, when etymologists, antiquarians, historians, missionaries, and reformers began to piece together the story of the European Gypsies, they returned again and again to the question of the origin and extraordinary longevity of these people, with their deep and extensive past in Europe. The narrative of their ubiquity and ancient presence in the West was almost always accompanied by assertions of their cultural uniformity: their nature was lasting and stable and everywhere the same. Commentators marveled that Gypsies had been in Britain from the first decades of the sixteenth century and had arrived in Germany a century before, possibly as early as 1417, and delighted in puzzling over their precise route of entry.1 Had they come from Egypt or from India? Were they descended from the Ishmaelites, “destined by divine proscription ever to remain a wandering irreclaimable people”?2 Or were they remnants of the ten lost tribes of Israel, or part of the “mixed multitude” that had fled Egypt with the Jews?3 Students of Gypsy history appear to have clung tenaciously to the ambiguity of the Gypsies’ lineage, as though the mystery of their origin were crucial to the role they played in the imaginations of scholars, writers, and readers alike. It seemed most remarkable that Gypsies had remained fundamentally unchanged for centuries and spoke a consistent and codified language, not “a fabricated gibberish,” as some had once believed.4 “They remain ever, and in all places, what their fathers were—Gipseys,” wrote Heinrich Grellman, the first important chronicler of European Gypsies, introducing a theme that often would be repeated. Life among varied and enlightened civilizations apparently had not transformed the Gypsies, and their customs and habits were both homogeneous and consistently anachronistic.5

Alongside this narrative of consistency and homogeneity, however, a counter-narrative took form. Although historians and proto-ethnologists did not explicitly challenge the dominant notion that Gypsies had a distinct and lasting character as a people, they, often inadvertently, acknowledged elements of variation, inconsistency, and assimilation. Gypsies certainly had a deep and discrete past in Europe, but they had not remained unchanged, nor were they everywhere, in all ways, the same. Grellman begins Dissertation on the Gipseys (1787) by arguing that the Gypsies’ “Oriental” attachment to custom and habit of remaining isolated from those among whom they lived accounted for their unvarying nature.6 But he goes on to undermine both the sense of their consistent identity and the notion of their absolute separateness. Early on, he catalogues the variety of names given to this people throughout Europe: the French call them bohémiens; the Dutch, Heydens; the Moors and Arabs, Charami; the Spaniards, gitanos; the Germans, Italians, and Hungarians, Tzigany; the Transylvanians, Pharaoh nepek; the Clementines in Smyrna, Madjub; the Bucharians, Diajii; the Moldavians, Cyganis; the English, Egyptians.7 This multiplicity of names, which unsettles Grellman’s own assertion that they “remain ever, and in all places, what their fathers were—Gipseys,” is related, of course, to the Gypsies’ much disputed ancestry (the French call them “bohémiens” believing that they came from eastern Europe, and so on). So in a fundamental way, Grellman implies, Gypsies were different things to different nations, and their essential identity differed widely from theorist to theorist. “Sometimes,” he muses, “the Gipseys are Hebrews, then Nubians, Egyptians, Phrygians, Vandals, Sclavonians, or … perhaps some other nation.”8

Grellman maintains that Gypsies did not intermarry with other peoples and so remained unchanged in bodily characteristics over generations. They were readily identifiable as a distinct and uniform race. But he also argues that their swarthy coloring was more the result of “education, and manner of life, than descent” and wonders how non-Gypsies “should … be able to distinguish a Gipsey if taken when a child from its sluttish mother, and brought up by some cleanly person.”9 John Hoyland, a Quaker historian of Gypsies in Britain, whose Historical Survey of the Customs, Habits, & Present State of the Gypsies owed a great deal to Grellman’s work, expresses similarly contradictory views of the Gypsies’ integrity as a people. He first claims that Gypsies never married anyone who was not of Gypsy extraction and then remarks that Scottish Gypsies, at least, were “much intermingled with our own national out-laws and vagabonds.”10 Perhaps trying to reconcile his own conflicting assertions, Hoyland insists that when Gypsies did marry “strangers,” the new members of the clan took on the manners of the Gypsies and their progeny always had “the tawny complexions, and fine black eyes of the Gypsey parent, whether father or mother.”11 The dominant myth of Gypsy identity, then, was that it was constant and consistent, while the strength of empirical observation, a comparative glance at Gypsies throughout the various European countries, and anecdotal evidence about intermarriage suggested a wholly different reality: one of mixture and variation, of an ancient presence that had, over centuries, become an integrated, although not wholly assimilated, part of European culture and had not remained completely insulated or unchanged in the nations of the West.12

Europeans favored the notion of Gypsy homogeneity because it reassured them about their own distinctness and national or “racial” integrity. The idea of an intermingled people raised anxieties about the permeability of boundaries between groups and the possibility of mixture on both sides of the presumed Gypsy–European divide. The common myth that Gypsies kidnapped so-called European children and raised them as their own expressed this nervousness about intermingling and accounted for it in a manner that apparently seemed more reassuring than the specter of willed miscegenation. (In the American context, of course, stories of racial blending and unaccountably dark “whites” or light dark-skinned people, focused on Native Americans, with whom Gypsies were often compared, and African Americans.) The accidental or forced mixing of races could explain why Gypsies, who were habitually described as raven-haired, swarthy, even black, sometimes had blue eyes and fair hair. But in England, at least, it might also account for those Anglo-Saxons who were uncharacteristically or inexplicably dark-skinned or dark-haired.13 Anglo-Saxon homogeneity was also a much-prized myth, and aberrant appearance or even character could be imagined, sometimes whimsically and sometimes earnestly, as the result of misplacing, losing, or mistakenly acquiring a child.

Stories that coupled Gypsies with kidnappings, foundlings, switched babies, and mistaken identities abounded in cultural lore and popular narrative. Gypsies appear to have lived close enough to settled communities to steal English babies and yet distant and peripatetic enough to keep such children hidden. A favorite and oft-repeated kidnapping legend concerned Adam Smith, rumored to have been taken by Gypsies as a boy for just a few hours. “It is curious to think,” wrote one particularly alarmist commentator in the mid-nineteenth century,

what might have been the political state of so many nations, and of Great Britain in particular, … if the father of political economy and free-trade … had had to pass his life in a Gipsy encampment, and, like a white transferred to an Indian wigwam, under similar circumstances, acquired all their habits, and become more incorrigibly attached to them than the people themselves; tinkering kettles, pots, pans, and old metal, in place of separating the ore of a beautiful science from the debris which had been for generations accumulating around it.14

This legend carried particular force as a parental admonition. If the great Smith, a man so important to the building of British civilization, found himself in danger of absorption into an alien tribe, so, too, might any careless child. The threat of kidnapping became a staple of nursery rhymes, lullabies, and teasing to coax children into proper behavior. But the opposite notion, that a Gypsy child could end up in the English world, had great imaginative force as well. Parents might scold a naughty or even an unconventional child by saying that the “tinkers” had stolen their real offspring and left a Gypsy in his or her place.

On the child’s side, of course, the fantasy of alternative parentage—what Freud called the family romance—often took the form of imagining more elevated, or nobler, ancestry.15 This was apparently so with certain Gypsies themselves. According to Walter Simson, a contemporary of Walter Scott and the author of an early series of articles on Gypsies for Blackwood’s, Gypsies, too, had their own version of family romance: “If … you enquire at the Gipsies respecting their descent, the greater part of them will tell you that they are sprung from a bastard son of this or that family of noble rank and influence, of their own surname.”16 But the fantasy of alternative parentage might also express an English child’s feeling of anomalousness or oddness—of not being ordinary or fully “English,” of not fitting in—and a Gypsy lineage was often invented as the likely or even wished-for explanation of difference. Many of those who wrote about Gypsies throughout the nineteenth century either imagined themselves or were imagined by others to have Gypsy ancestry, and many were drawn to stories of people who had, for one reason or another, fled the English world and been absorbed into that of the Gypsies. Simson recounts the tale of a gentleman of considerable wealth and property who “abandoned his relatives” and married into a Gypsy family, with whom he traveled the countryside. It was said that at times he resided on his own estate, “disguised, of course, among the gang, to the great annoyance of his relatives, who were horrified at the idea of his becoming a Tinkler.”17 Simson himself, when he roamed throughout Scotland in the 1820s, engaged in what he called “Gipsy-hunting,” collecting Romany customs and vocabulary, and came to be known by the Gypsies themselves as a “gentleman Gipsy.”18 He was among the first, along with George Borrow, of the “Romany rye,” the scholar-gypsies who became aficionados, patrons, and fellow travelers of the Gypsies.19

As fascinated as nineteenth-century historians and other commentators were by the separateness and distinctness of Gypsy identity, then, they also were powerfully drawn to the exchanges, crossings over, and porous boundaries between the Gypsy world and their own. Real and imagined meetings with Gypsies, the myth of kidnappings by Gypsies, and the frequent translation of individual experiences into stories with great cultural appeal and currency helped establish Gypsy plots and characters, as well as scenes of encounters with Gypsies, as common features of nineteenth-century fiction. The Romantic fascination with the foreign and exotic and the hospitable form of the bildungsroman, with its emphasis on riddles of origin and identity, also prepared the ground for Gypsy subjects. But the single most important literary influence on the nineteenth-century fascination with Gypsies and their role in the cultural imagination was Scott’s novel Guy Mannering. The narrative became a source both for historians, who recycled Scott’s account of Scottish Gypsies as though it were authoritative, and for novelists and poets, who used Guy Mannering’s kidnapping plot and Gypsy heroine as prototypes for their own inventions. Scott’s novel works against the myth of a discrete Gypsy identity—although it creates a myth of another sort in the figure of Meg Merrilies—and gives the Scottish Gypsies a local and distinct history that emphasizes their status as a hybrid and ancestral people.

Prototypes and Ancestors

In his novel Guy Mannering, or, The Astrologer (1815), Walter Scott offers his readers a version of the history of Gypsies that emphasizes their deep and mystical presence in the Scottish past, their intermingling with the Scots themselves, and their vulnerability to the vagaries of historical, political, and economic change. His are not Gypsies of a static and constant character, impervious to alteration and untouched by other people and ways of life, as many commentators in this period imagined them. Scott set his novel in the 1770s and 1780s, reflecting both his personal and familial experience of Gypsy history and the sense, articulated by his colleague Walter Simson, that the late eighteenth century had been the Gypsies’ heyday, after which their status and viability in Scotland declined.20 But Scott’s Gypsies also occupy an iconic place in the collective cultural memory of the Scottish people and seem, at times, to stand in for the prized national past that Scott, as an antiquarian, was committed to retrieving.21 Their association with an ancient and dimly remembered history, a memory of origin, and a complex identity is played out in the novel on the level of the individual experience of the young hero, Harry Bertram, and his connection to the Gypsy “sibyl,” Meg Merrilies, one of Scott’s most charismatic and celebrated characters. The memory of this primal figure links Bertram to his past, helps him reconstruct his nearly erased identity, and serves as a confirmation of the need to preserve—or, at least, remember—the cultural amalgam of which the Gypsy is a part.

Meg Merrilies, “harlot, thief, witch, and gypsy,” had a life of her own outside Scott’s novel throughout most of the nineteenth century and played an archetypal role in popular culture, the meaning of which is all but lost to us.22 She was the subject of the poem “Meg Merrilies” (1818) by John Keats, inspired another called “The Gipsy’s Malison” (1829) by Charles Lamb, became the central character in a successful dramatization of Guy Mannering that featured the famed Sarah Egerton as Meg, and was painted in at least seven portraits between 1816 and 1822.23 This “Meg-mania,” as one critic has phrased it, underscores the powerful, imposing, and exotic visual qualities of this figure: her great and mannish height; her wild-haired and red-turbaned head; her garb, which combines “the national dress of the Scottish people with something of an Eastern costume”; and her air of “wild sublimity” (1:36).24 She is written as a virtual stage character, compared explicitly in the narrative with Sarah Siddons, and always evoked pictorially, as though Scott meant her for the subject of a picturesque tableau (2:284).25 But Meg Merrilies also captured the imagination of Scott’s audience as an emblem of fate and a reader of the future—she is referred to as an “ancient sibyl”—and as an ancestral figure. Neither wholly female nor wholly male, she is a woman of “masculine stature,” with a voice whose “high notes were too shrill for a man, the low … too deep for a woman” (1:19, 203).26 Hybrid in a variety of ways—male and female, Scottish and “Eastern”—she transcends distinctions of sex and nation and occupies the position of an ur-parent or original forebear.

Walter Scott himself claimed a wild and mixed ancestry. From his antiquarian research, the respectable lawyer’s son drew what John Sutherland calls a “mythic genealogy.”27 It began with a sixteenth-century outlaw border hero and his ferocious daughter-in-law Meg Murray, the “ugliest woman in four counties,” whose name must have influenced Scott’s choice for his Gypsy witch. Another favorite antecedent was the seventeenth-century “Beardie,” a vehement and loyal Jacobite whose portrait hung on the wall of the novelist’s study. His attachment to these ancestors and to the stories of their exploits extended to his belief that he resembled them physically, bore no likeness to his own mother and father, and was a “throwback” to earlier generations of the family.28 The romance of this undoubtedly invented—or at least chosen—lineage is reflected in Guy Mannering and conjoined with Scott’s memories of the legend of Jean Gordon, a Jacobite Gypsy of the Yetholm clan, and her granddaughter, Madge.29

Both Gordons were reputed to have been six feet tall—a trait that Scott gave to Meg Merrilies—and to have made lasting impressions on the people, especially the children, who met them. Jean’s legend centered on her fierce and fatal loyalty to the Jacobite cause, a political disposition that Scott could and did romanticize—in his accounts of Jean Gordon and in Waverley (1814)—from a distance of some seventy years. For Walter Simson’s series of articles for Blackwood’s, he wrote a description of Jean Gordon’s death:

She chanced to be at Carlisle upon a fair or market day soon after the year 1746, where she gave vent to her political partiality, to the great offence of the rabble of the city. Being zealous in their loyalty when there was no danger, in proportion to the tameness with which they had surrendered to the Highlanders in 1745, the mob inflicted upon poor Jean Gordon no slighter penalty than that of ducking her to death in the Eden. It was an operation of some time, for Jean was a stout woman, and, struggling with her murderers, often got her head above water, and while she had voice left, continued to exclaim at such intervals, “Charlie yet! Charlie yet!” 30

Scott ends his account of the legend of the Gypsy’s death by inserting his own childhood response to the event. “When a child, and among the scenes which she frequented,” he writes, “I have often heard these stories, and cried piteously for poor Jean Gordon.” The tale of sacrifice and stubborn allegiance moved the child and, ultimately, made its way into the Gypsy character and novel of 1815. Almost eighty years later, Andrew Lang, Scottish man of letters and folklorist, wrote an introduction to an edition of Guy Mannering that includes this excerpt from the Blackwood’s article and then moves on to talk of Jean Gordon’s granddaughter, Madge. Lang claims that his own “memory is haunted by a solemn remembrance of a woman of more than female height, dressed in a long red cloak, … whom I looked on with … awe.”31 He quotes yet another witness, who recalled this “remarkable personage, of a very commanding presence and high stature,” from his own childhood: “I remember her well; every week she paid my father a visit for her awmous [alms], when I was a little boy, and I looked upon Madge with no common degree of awe and terror.” The complex association between these outsize female figures and deeply etched memories from childhood form a basis for the affective and psychological drama of Harry Bertram’s story in Guy Mannering.

One final aspect of Scott’s personal experience proved crucial to the particular history of the Scottish Gypsies that he wrote into Guy Mannering. In the year preceding the publication of the novel, he had taken a tour of northern Scotland and seen the effects of the “Clearances,” landowners’ efforts to evict old tenants from their property in order to make better economic use of their farmlands.32 Although a landlord himself and so identified with landlords’ interests, he lamented the evidence he saw of these changes in social relations and landscape during his trip to the Orkney Islands. “How is the necessary restriction to take place, without the greatest immediate distress and hardship to these poor creatures?” he wondered of three hundred displaced tenants who had been living on Lord Armadale’s estate. “If I were an Orcadian lord,” he continued in his diary of the journey, “I feel I should shuffle on with the useless old creatures, in contradiction to my better judgement.”33 Scott’s ambivalence about the social and moral consequences of the “Clearances” informed the plot of Guy Mannering, in which it became a question about the Scottish Gypsies’ place both in society and in history, as well as a way of dramatizing the individual and communal dangers of banishing the past.

Dispossession

Intertwined with the history of Meg Merrilies and her Gypsy tribe in Guy Mannering is the story of a lost heir, Harry Bertram, and his Oedipus-like saga of wandering, exile, and recovery of identity. Bertram, the prospective laird of Ellangowan, and the Gypsies who have lived on his family’s lands for generations share the fate of dispossession; indeed, it is the “clearance” of the Gypsies from their home at Ellangowan that appears to lead to the forced separation of young Harry from his patrimony. The plot turns on the drama of kidnapping, playing pointedly on the common association of Gypsies with that crime, and the novel casts India—symbol of the British Empire—as the offstage scene of exile and ill-fated adventure. Scott employs the Gypsies—and Meg Merrilies as their representative—to endorse a particular relationship with the past, a notion of polyglot culture (Sutherland calls the novel a “maelstrom of languages, jargons, idiolects, and dialects”), and a wariness of new social and economic arrangements.34 The mechanism for realizing this vision in the novel is memory, particularly the semiconscious, almost hallucinatory memory of earliest, infantile attachment to a place and, more important, to an archetypal, surrogate mother.

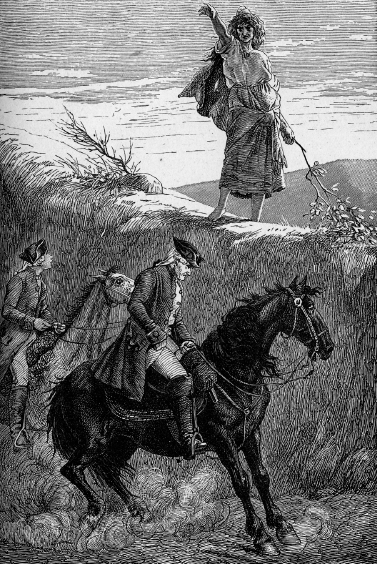

The novel begins, like the story of Oedipus, with a prediction about the ultimate fate of a child. An Oxford-educated astrologer, the Guy Mannering of the title, has wandered northward to Kippletringan, in Scotland, and finds himself at Ellangowan House just as its owner’s son and heir is being born. Mannering casts the baby’s horoscope, his celestial calculations revealing that the child Harry will meet with captivity or sudden death and will be especially vulnerable at three crucial points in his life. Mannering is intrigued by the Gypsy Meg Merrilies’s spinning, a competing means of divining the boy’s future (figure 5). He encounters her as he wanders through the ruins of the original Ellangowan Castle, the ancient seat of the family, where she sits in an apartment, weaving together multicolored threads and intoning a “charm”—“Twist ye, twine ye!” (1:37). The spinning and chanting culminate in Meg’s measuring the length of the thread she has produced to determine the boy’s future. She reckons for the child not a “haill” but a long life, a span of seventy years marked by three traumas or breaks and subsequent recoveries. Unlike Mannering, Meg sees in Harry Bertram’s fate the possibility of triumph: “he’ll be a lucky lad an he win through wi’t” (1:37).

This appearance of Meg in the novel is notable for a number of reasons. First, her prophecy is placed in opposition to Mannering’s. Will the Gypsy’s or the astrologer’s prediction prove correct? Aside from setting in motion the mystery of the plot, this question pits the erudition of the English scholar against the wild ways of the Scottish Gypsy. Earlier, the laird has hinted at this competition when Meg offers to tell the child’s fortune as soon as it is born and the laird rejects her offer, assuring her that “a student from Oxford that kens much better” how to make such predictions will do so by the stars instead (1:22). Second, the scene locates Meg within the decaying walls of the laird’s ancient castle, not by her cauldron in a forest or Gypsy encampment, and so identifies her with the “auld wa’s [old ways],” as she will later refer to the traditions of patronage and privilege associated with the landowning class. As we shall see, the haunting and sublime site of these ruins plays an important role in the hero’s eventual recovery of memory and self. Finally, Mannering glimpses the Gypsy through “an aperture.” Spied on as she performs her secret rituals—“he could observe her without being visible himself”—she assumes an elevated and powerful place, conveying to Mannering the “exact impression of an ancient sibyl” rather than the air of a deranged Gorgon, which she conveyed earlier (1:22). A figure likely drawn from fairy tale as well as myth, Meg is associated with fate and the hidden rites of femaleness—not to say, female sexuality.35 Critics have noticed the frequency with which characters in the novel perceive events dimly, through apertures or small openings.36 It is Meg who is most often spied in this way, and her power as a figure in the novel (and, possibly, beyond it) derives from her association with what Freud calls “primal phantasies”—that is, the memory or fantasy of something secret, sexual, and hidden that is only partly seen and understood.37

As Harry grows up, Meg’s “ancient attachment” to the Bertram family is transferred to the child. When he is ill, she lies all night outside his window and chants rhymes to speed his recovery. When he wanders from home to “clamber about the ruins of the old castle,” she follows and retrieves him. When he ventures forth to places unknown, she “contrive[s] to waylay him …, sing him a gypsy song, … and thrust into his pocket a piece of gingerbread” (1:66). So constantly does she attend to him and watch over him that Harry’s mother, who is sickly, indifferent, and pregnant with a second child, becomes suspicious of the woman who has, in effect, taken her place. Harry’s rambling ways and Meg’s presence cause general concern, and his tutor, the sentimental Dominie Sampson, fears that “this early prodigy of erudition [will] be carried off by the gypsies, like a second Adam Smith” (1:67). Both Harry’s mother and Dominie misread Meg’s role: she protects rather than threatens the child, and her loyalty to the Bertrams, rather like Jean Gordon’s loyalty to the Stuarts, is indestructible. But the fate of Adam Smith is not to be avoided, and at five, the first of the child’s vulnerable ages according to the astrologer’s predictions, Harry is kidnapped.

With Harry’s kidnapping, Scott sets up the expectation that the Gypsies have committed a crime “consistent with their habits,” but he also gives the reader reason to believe that the crime is an act of at least understandable, if not forgivable, vengeance. Scott inserts the Ellangowan Gypsies into a history that combines a particular interpretation of their presence in Scotland with the recent events, not directly involving Gypsies, of the “Clearances.” In chapter 7 of the novel, he evokes a Gypsy history that begins with segregation and outlawry; moves deliberately to integration, domestication, and salutary coexistence; and ends with banishment. A century earlier, the narrator records, Gypsies were little more than “banditti” who roamed about the countryside, stealing, begging, drinking, and fighting. In time, however, they lost the “national character of Egyptians” through intermarriage with Highlanders and thus became a “mingled race,” both their numbers and the “dreadful evil” they produced decreasing (1:57 [emphasis added]). They learned trades—primarily tinkering and earthenware-making—and practiced the arts of music, fortune-telling, and legerdemain. Scott’s Gypsies not only are a mixed and substantially tamed group, but also maintain a symbiotic relationship with Scottish landowners or “settlers.” Meg’s tribe, for example, has dwelled on the estate of Ellangowan for generations, enjoying the lairds’ protection and paying in return with services and combat in times of war. Scott also identifies the Gypsies ethnologically: they are “Pariahs,” like “wild Indians among European settlers,” and, although attached to a settled group, are judged according to their own “customs, habits, and opinions” (1:60).38 Separated by class and culture rather than by nationality from the landowning Scots, they live by different practices and mores but enjoy a “mutual intercourse of good offices” (1:61). Scott takes pains to establish an identity for the Gypsies that is subject to historical change and that exists and evolves in a process of exchange with other groups. They are not a timeless, insular, or undiluted people, as many observers and historians of the Gypsies had maintained. By the start of the narrative, then, Scott’s Gypsies are part of the fabric of disparate groups that make up the Scottish nation. The laird of Ellangowan interrupts this history of amelioration and integration when he banishes the Gypsies from his land and sends them into exile.

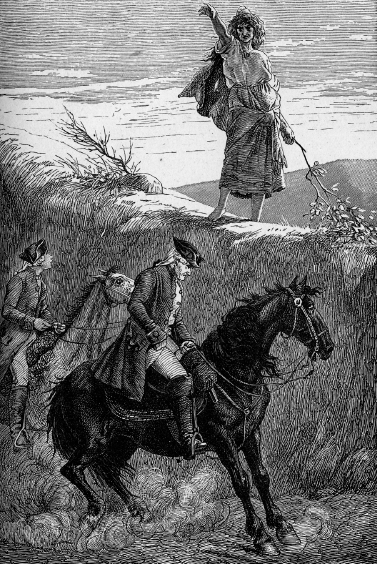

Although the laird has ignored trespassing laws, he now feels compelled to enforce them because he has been made a “conservator of the peace.” He issues an order to remove the Ellangowan Gypsies, sets a deadline, and then resorts to “violent measures of ejection” (1:68). Like the lords of Orkney, whose enactment of the “Clearances” Scott had noted with great ambivalence, the laird of Ellangowan separates this tribe from its “ancient place of refuge” (1:70). He observes the exodus of the Gypsies from his lands with a “natural yearning of heart” toward those he has known for so long (figure 6) and is confronted suddenly with the figure of Meg Merrilies, dressed in red turban and looking like a “sibyl in frenzy” (figure 7). In a set piece that was later sketched, painted, acted on the stage, and described in verse, Meg curses Bertram for this rude displacement of her people:

There’s thirty hearts … yonder, from the auld wife of an hundred to the babe that was born last week, that ye have turned out o’ their bits o’ bields, to sleep with the tod and the blackcock in the muirs! Ride your ways, Ellangowan. Our bairns are hinging at our weary backs; look that your braw cradle at hame be the fairer spread up,—not that I am wishing ill to little Harry, or to the babe that’s yet to be born,—God forbid,—and make them kind to the poor, and better folk than their father! (1:72)39

Although, if Meg is to be taken at her word, the laird’s children have nothing to fear from her, and although there are smugglers close at hand who might easily engage in the crime of kidnapping, Harry’s subsequent disappearance is blamed on the Gypsies and understood as a direct result of this curse. The novel offers the reader the example of Adam Smith, the lore of Gypsy kidnappings, and the specter of a fierce and wrathful Meg Merrilies, but it does so in tandem with a crime committed by the laird against the Gypsies, and, in the end, it controverts most of the evidence that associates the Gypsies with this misdeed. Meg is nonetheless banished from the country as a “vagrant, common thief, and disorderly person,” a charge commonly used to rid locales of Gypsies throughout Britain and Scotland (1:97).40 The irony is obvious: Meg is banished as a vagrant because she has been ordered off the land that was her home. The act that exiles her also makes her an outlaw. By the middle of the novel, both Harry Bertram and the Gypsies have become dispossessed and homeless wanderers.

Empire and Its Discontents

Myths and narratives of Gypsy kidnappings, like that of Adam Smith, would dictate that Harry Bertram—if, indeed, taken by Meg or her people—be raised as a Gypsy in an unseen but nearby enclave. Such is not the fate of Harry, who was taken to Holland by smugglers immediately after his kidnapping and forcibly apprenticed to a commercial house, before being posted by the firm to India. In the unnarrated seventeen years between Harry’s kidnapping and his return to Scotland, Guy Mannering also ended up in India, where he has had a successful military career but a chaotic and miserable personal life. In retrospect, the narrative informs the reader of certain salient events that occurred abroad, most important a falling out between Mannering and Harry—now called “Brown” and unknown to Mannering as Harry Bertram—who, detesting the life of a counting-house clerk, became a soldier in Mannering’s regiment. The older man suspected Brown of being his wife’s lover, and the two fought a duel in which Mannering was supposed to have killed Brown. Mannering’s wife died in a state of grief and alienation, leaving a daughter, Julia, possessed of “piercing dark eyes, and jet-black hair of great length, … vivacity and intelligence, … shrewdness … [and] humorous sarcasm” (1:177). Neither dead nor living the life of a Gypsy, Brown/Bertram, prompted by inchoate desires, returns to Kippletringan. In the intervening years, his mother has died in childbirth, and his father has perished a broken, presumably heirless man, his estate sold to an arriviste named Glossin. Brown’s identity is a mystery to all, including himself. Mannering, longing to redeem his life and that of his daughter, also returns to Scotland and the vicinity of Ellangowan House, hoping to purchase the estate and there “nurse the melancholy that was to accompany him to his grave” (1:122).

Some of the most interesting recent analyses of Guy Mannering have focused on its imperial themes and motifs, what Katie Trumpener calls the novel’s inauguration, along with Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814), of “a new analytic model for describing the workings of the imperialist unconscious.”41 Peter Garside points to the text’s frequent yoking of Gypsies and Indians and concludes that Scott knew current theories identifying India rather than Egypt as the Gypsies’ land of origin. He also argues that the eviction of the Gypsies from Ellangowan reflects not only the domestic “Clearances” that Scott observed, but the expulsion of villagers in Bengal by landowners attempting to enlarge their estates.42 Trumpener’s ambitious reading of Guy Mannering emphasizes the way it continually folds the domestic into the imperial and the imperial into the domestic, draws parallels between misdeeds abroad and those at home, and generally advances an “interpenetration” of these two spheres in narrative, ideological, and psychological terms.43

These readings seem compelling, particularly as correctives to the longstanding critical silence about what Edward Said calls the “structure of attitude and reference” created by imperialism in Western culture and, especially, British fiction.44 Guy Mannering may be among the first English or Scottish novels to contain an offstage colonial interlude in which disinherited sons and penniless scholars go abroad to make fortunes, have adventures, or at least make lives for themselves. This narrative pattern was to be repeated again and again in nineteenth-century fiction. But, having observed this, I want to identify with a bit more precision what this interlude signifies in Scott’s novel. If, by the end, the “wide world and its problems disappear,” as Trumpener writes, if there is finally a suppression of political and moral complexities associated with empire, there is also in the novel a decidedly skeptical view of imperial adventure.45 For all that empire proves an arena for personal advancement, it also threatens a potentially dangerous rupture with a vital domestic past.

In Guy Mannering, India is a site of anarchic passions, near-fatal Oedipal dramas, and, most important for Scott, suspect means of achieving wealth and position and thereby overturning traditional hierarchies of privilege and responsibility. It is a place of exile that enriches some, like Mannering, whose life it also destroys, and thwarts others, like Harry, whose very degradation enables him ultimately to reclaim the privilege that is rightfully his. The machinery that threatens Harry’s inheritance and the renewal of the House of Ellangowan combines and links the efforts of the villainous smuggler Hatteraick, who engineers the boy’s kidnapping; the grasping and corrupt magistrate Glossin, who colludes in the kidnapping so he can seize Ellangowan; and the Dutch commercial house Vanbeest and Vanbruggen, where Harry is placed by the “brutal tyrants of his infancy” (the smuggler and an accomplice) and which sends him to India (2:291). Glossin, who seeks to dismantle the old ways through an illegitimate use of power, is the novel’s central villain: through him, colonial commerce is associated—perhaps even equated—with the common crimes of smuggling and kidnapping. Colonial wealth and power, like Glossin’s new money, also threaten the old ways, in economic and class terms. Scott indicates his wariness of—not to say, disdain for—the kind of status that is to be gained through both colonial commerce and the rise of a ruthless arriviste like Glossin by a small detail: the usurper of the Bertram property has commissioned an “escutcheon for the new Laird of Ellangowan” and must wait his turn until fake coats of arms are produced for two Jamaican traders (2:147).46 All these pretenders are alike, and all are suspect. Glossin’s pursuit of wealth robs Harry of his birthright and, like colonial commerce, promises a kind of geographic dislocation that disrupts connections with the past and the places that enshrine it. As Ian Duncan puts it, “Glossin establishes a false order, based on ambition, avarice and fraudulent legality, the evil psychic energies of historical change.”47 The bogus nobility of Glossin and the Jamaican traders unites them in the process of regrettable change and, by implication, the perpetration of dislocations of new wealth and colonialism.

For Harry Bertram, rootedness in place and past constitute the very identity that he has lost. His return from India and exile will restore this identity, and it is Meg Merrilies, the figure most deeply associated with his beginnings, who will act as the prime agent of that restoration. The tragic Oedipal story of Harry’s presumed affair with Mannering’s wife and nearly fatal duel with his father-surrogate, Mannering, is to be replaced by a triumphant Oedipal story of Harry’s filial redemption, reunion with the originary mother Meg, and union with Julia Mannering, whose dark beauty and forceful character suggest a tamed—and thus acceptable—version of the Gypsy.48 The treachery of Mannering’s misplaced jealousy, likened by him to the rage of Othello, is traded for the heroism of another racially marked, although indigenous, other, the Scottish Gypsy Meg Merrilies (1:117).

Primal Memories

Like an amnesiac, Brown/Bertram must relearn his identity, and it is, first of all, his encounters with Meg, still on the scene, that produce this gradual recognition and retrieval of the past. The sight of Meg triggers memories of certain primal experiences that, at the outset, he cannot quite place or distinguish from dreams: “He was surprised to find that he could not look upon this singular figure without some emotion. ‘Have I dreamed of such a figure,’ he said to himself, ‘or does this wild and strange-looking woman recall to my recollection some of the strange figures I have seen in Indian pagodas?’” (1:204). The answer to both speculations is, of course, no, and, although the question implicitly links Gypsy and Indian, it also distinguishes them from each other.49 Meg’s foreignness is only apparent or, perhaps, only partial, for she connects Harry to an authentic and specifically local past. Memory is not simply personal, not simply the agent of a retrieved identity, but also historical, geographical, and essential to the restoration of a particular social order. And it is Meg, the Gypsy, who is at the center of memory for Harry. She is also the one who has worked surreptitiously, even in his absence, to keep his inheritance within his reach. Meg “occupies the site of origins,” observes Ian Duncan, “[and] tirelessly guides, instructs, saves and provides until the homecoming and recognition are fulfilled.”50

Because Glossin, the new owner of Ellangowan and engineer of Harry’s removal as a child, wants to obliterate the past, memory is his enemy. In a highly dramatic, gothic scene of recognition, the returned Harry approaches Ellangowan Castle, in whose ruins Guy Mannering first saw and heard Meg spinning the child’s fortune. Harry, still struggling to make sense of the hazy memories evoked by seeing Meg and Ellangowan and now described as “the harassed wanderer” (having become a species of vagrant or Gypsy himself), muses on the eerie sensation of déjà vu:

“Why is it,” he thought …, “why is it that some scenes awaken thoughts which belong, as it were, to dreams of early and shadowy recollections such as my old Brahmin Moonshie would have ascribed to a state of previous existence? Is it the visions of our sleep that float confusedly in our memory, and are recalled by the appearance of such real objects as in any respect correspond to the phantoms they presented to our imagination? How often do we find ourselves in society which we have never before met, and yet feel impressed with a mysterious and ill-defined consciousness that neither the scene, the speakers, nor the subject are entirely new …? It is even so with me while I gaze upon that ruin.… Can it be that [it has] been familiar to me in infancy?” (2:135)

The ruins, like Meg herself, spark in Harry a primal memory, indistinguishable from dream or from the psychological trick of déjà vu. Both connect him to his childhood, when he clambered on the ruins and Meg followed him, as well as to his family’s ancient history. This history—personal, familial, and in some sense national—is what exile in India and the usurper Glossin threaten to interrupt, to sever. As Harry contemplates the ruined castle, Glossin approaches and, for the first time since Harry’s return, recognizes him. Instinctively, Glossin knows that he must be cautious “lest he should awaken or assist, by some name, phrase, or anecdote, the slumbering train of association” (2:137 [emphasis added]). It turns out to be a phrase—the Bertram motto—that awakens certain associations in Harry, prompting him to remember a rhyme and then a ballad from his childhood.51 When Glossin proceeds to curse ballads and balladeers, Scott, for whom both ballads and Gypsy lore were products of antiquarian researches into Scotland’s precious past, marks him indelibly as a man who imperils memory, culture, history, and the future.

Brought by memory and association back to the truth of his identity, Harry is embraced by the friends of his youth as an enfant trouvé. Hazy memories of the kidnapping seep into his consciousness, and he recalls, above all, falling into the arms of a tall woman “who started from the bushes and protected me for a time” (2:249). Gathered with the retainers of the old laird, Harry sees Meg appear again before him, “as if emerging out of the earth” (2:276). In a scene that rivals in its almost operatic theatricality that of Meg’s cursing of Harry’s father, the Gypsy is evoked as a towering, “gigantic” shape that belongs as much to ancient, elemental forms of nature as to humankind. She rises from the ground, like a tree or a rock, and, in her “wild sublimity,” she is a figure of prophecy, primeval origin, and justice. Just as she protected the rambling and then the abducted child, she has looked after his interests in his absence, knowing—because of her own predictions—that he would live a long life. The miniature exiles and returns of his earliest childhood adventures are replayed in the exile abroad and return to Scotland of his adulthood. “I shall be the instrument,” Meg tells Harry, “to set you in your father’s seat again” (1:258). She exposes the smuggler Hatteraick, who spirited Harry off to Holland, and, even more important, the role of Glossin, who supported the kidnapping because it worked to his advantage. For this, she is shot and killed by Hatteraick in the last pages of the novel.

But Harry, a fortunate Oedipus, who has happily survived the efforts of those who tried to destroy him as a child, will be reunited with his lands and his inheritance. Meg Merrilies dies a martyr to the restoration of the Ellangowan lineage and to the resumption of the “auld wa’s.” Harry gazes on the “wild chieftainess” as she lies dead before him and cries over the corpse of “one who might be said to have died a victim to her fidelity to his person and family” (2:305). Meg Merrilies mimics the heroic Jean Gordon, who died a similarly stubborn victim to fidelity and who, like Scott’s Gypsy, remained loyal to a group of people whose interests were not obviously her own. Scott’s hero reproduces the novelist’s own boyhood sorrow as he “cried piteously” for the poor woman who had drowned rather than betray the Jacobite cause. But if Meg Merrilies helps restore Harry’s title and family inheritance, she also links him, through her very being and maternal relationship to him, to a more ancient and fundamental lineage, one that has deep roots in the Scottish past. And although the novel must culminate in the confirmation of Harry’s legitimacy, it also flirts with and produces a kind of shadow illegitimacy for him. Glossin tries to claim that Harry is a bastard, his father’s “natural son,” and thus not the legitimate heir to the Ellangowan property (2:313). To prove him wrong, Harry’s supporters introduce the laird’s actual illegitimate son, a seafaring man from Antigua (no less), thereby establishing a double for Harry Bertram whose own vexed origins help maintain the sense of Harry’s complicated and symbolically “mingled” lineage.

The Middle Way

What, then, does Guy Mannering, a story of kidnapping and restored inheritance, suggest about the discursive role of the Gypsy? And what was the novel’s legacy in the nineteenth century, as it influenced literary representations of Gypsies, launched the enduring and generative figure of Meg Merrilies, and helped determine the “truth” of Gypsy character in the general culture? To begin with, the novel responds to and deploys the myth of Gypsy kidnappings in order to expose it as just that—a myth—and makes the representative Gypsy figure protective of rather than a threat to both the life and the rights of the disinherited laird. It does so by pointing a finger at the avaricious upstart Glossin, the real criminal, and by suggesting that the new ways of gaining status and wealth are far more insidious than the old ways of vagabondage and patronage, which the Gypsies and the lairds embody. But the effect of this exoneration, as it were, of the suspected kidnappers is a complicated business. The trope of Gypsy kidnapping is still at the center of the plot; Harry Bertram does, after all, fulfill the legend of Adam Smith; and the Gypsies are given a powerful and important motive for a deed that they nonetheless did not commit.52 It is possible that Scott’s nineteenth-century readers were better placed to understand his glorification of Meg than we are, in large part because of the particular contours of Scott’s conservative impulses. His vindication of the Gypsies is part of a more complex conservatism than some have allowed, as is his wariness of imperial adventure and gain. Georg Lukács defines Scott’s conservatism and “honest Tory[ism]” as an attempt to chart for himself a “middle way” between the “ardent enthusiasts” of the Industrial Revolution and capitalist growth, on the one hand, and their “pathetic, passionate indicters,” on the other.53 Scott is able to sympathize with those who are displaced by new economic and social arrangements, just as he is able to celebrate the greatness of the clans and their “primitive order,” but he is unable to repudiate fully the new developments responsible for this displacement.54 The “middle way” of Guy Mannering includes both justification and historicization of the Gypsies’ role in Scottish culture, as well as the recognition that modern “clearances” must necessarily disperse them and remake Ellangowan as an estate free from their ancient presence.

Meg’s role in Harry’s preservation not only vindicates the Gypsies’ honesty, but also upholds privilege and indigenous tradition, which ought to include making room for the now dispersed Gypsies on the land of Ellangowan. With Meg’s death, however, and the scattering of her people—all twelve of her children are, like the twelve tribes of Israel, dispersed into an unnamed diaspora—this seems a hollow proposition, and the novel’s conclusion suggests that only in death will Meg truly be believed: “When I was in life, I was the mad, randy gypsy that had been scourged and banished and branded … what would hae minded her tale? But now I am a dying woman, and my words will not fall to the ground” (2:300). Scott’s vision is, nonetheless, ultimately an inclusive and reformist one. Even as the elder Bertram banishes the Gypsies from his land, he feels remorse at the thought that, although they were indeed idle and vicious, no one had “endeavoured to render them otherwise.… Some form of reformation ought at least to have been tried” (1:70–71). Scott’s Gypsies, already a “mixed,” hybrid people, are part of an imagined multicultural nation, their potential return to Ellangowan a conservative but utopian symbol of cultural retrieval. Indeed, Scott uses a Gypsy as the mouthpiece for tradition and places her squarely in the center of the drama of both personal and cultural memory. You suppress these people at your peril, his story implies; yet the novel ends with their presence fully erased.

Is Guy Mannering, then, a story of extinction, a vision of the Gypsies’ salutary disappearance from the Scottish scene?55 Yes, in the sense that the Ellangowan Gypsies cease to be a visible presence by the close of the novel. But they are dispersed—not extinct—and already intermingled with other Scottish groups. Their local legacy, in the form of the new laird, suggests that their ways and influence survive. Gypsy identity has been transferred, albeit temporarily and obliquely, to the new laird. Harry has wandered the world dispossessed, homeless, nameless—Gypsy-like—and, as a consequence, has returned a laird unlike any his father might have imagined. When Meg curses Harry’s father, she also issues a kind of blessing in wishing that his children might be kinder to the poor and “better folk than their father” (1:72). On Harry’s return as an adult, she predicts that he will be “the best laird … that Ellangowan has seen for three hundred years” (2:200). It is his exile and experience of suffering, which he shares with the Gypsies, that will enable him to be a superior laird. So, too, has his filial tie to Meg Merrilies, the symbolic begetter of a reinvigorated Scottish line, connected him spiritually and viscerally to ancient modes of being and ruling. And his marriage to Julia Mannering, she of the long, jet-black hair and shrewd nature, joins him to a woman who bears at least a fleeting resemblance to the Gypsy Meg.56 As Michael Ragussis has observed in his discussion of Ivanhoe, Scott envisions history as “a lengthy process of racial mixture, … a record of difference.” Just as Ivanhoe debunks the fantasy of English purity by “delineating the mixed Saxon and Norman genealogy of the modern Englishman,” so does Guy Mannering suggest that Gypsies, Highlanders, lairds, and vagrants are part of a mongrel Scottish inheritance.57

Meg’s Progeny

The legacy of Scott’s novel to nineteenth-century ways of imagining Gypsies begins with Meg Merrilies. She lived beyond the novel—in popular culture, on stage, and in verse—but her longevity as a character certainly cannot be ascribed solely to her Gypsy identity. To the degree that she established an archetypal form of Gypsyhood, however, her ancestral role, physical size and shape, and association with childhood memory are crucial. She is the agent and subject of distant, hazy, and early recollections, associated by the hero with maternal solicitude and infantile sensations. Identified, too, with a state of mind that mixes memory and dream—something glimpsed but perhaps really only imagined—she seems to exist in the realm of “primal phantasy,” the term that Freud used to describe just such ambiguous recollections. It is possible that Scott was also engaged in imagining or inventing what Freud would later call the “phylogenetic endowment” of such fantasy-memories and Jung would describe as the “primordial image … dormant in the collective unconscious.” For Freud, this “phylogenetic endowment” allows individuals to reach back in memory beyond their own experiences and personal recollections into “primaeval” events. For Jung, the persistence into the present of images from myths and early religions suggested that “archetypes” exist in the “mental history of mankind.”58 The power of these theories as credible accounts of the individual psyche is not the issue: rather, I want to suggest that Scott’s novel seems to claim for Meg, and for the Gypsies whom she represents, just this primeval, archetypal realm that Freud and Jung were to elaborate.59 Meg is part of the unconscious memory of not only Harry Bertram but the Scottish nation: an ancestral figure, an originary figure, who nonetheless is not of the legitimate ancestral line.

Meg occupies a place in Harry’s memory that, in a far more domesticated form, Peggotty occupies in David Copperfield’s. The two women, alternative mothers, large in form and alien in social class and custom, fill a “vacancy in [the] heart” of the boy and represent a kind of maternal physicality that does not partake of middle-class femininity.60 Both are associated with states of half-sleep—David remembers Peggotty seeming to “swell and grow immensely large” as he falls asleep as a child—and with recollections of boyhood trauma from which these women had protected them.61 Both traumas involve separation: attempts to wrench the boys from their homes—kidnapping in one case and assault by a stepfather in the other—and the deaths of their mothers in childbirth. But Peggotty is, of course, the gentled, Victorian version of Meg. She is neither wild nor mysterious, not the outraged representative of a shunned people, and, although large and shapeless, not manlike in stature.

Indeed, Meg’s combination of feminine and masculine characteristics—“androgynous” seems too tame a word for her—reflects the anomalous sexuality with which Gypsies would continue to be associated in the first half of the nineteenth century. Observers often commented on the sensuality and “lasciviousness” of Gypsy women. Heinrich Grellman described the seductive dancing of female Gypsies, and John Hoyland regretted the “indecent gestures” of young girls who rambled and danced with their musician fathers for a few pennies.62 While these writers decried the louche performances of these women, later authors deployed the Gypsy seductress as a stock figure, the welcome object of male desire. But early in the century, literary texts often used Gypsies to represent ambiguous, masculinized, and sometimes celibate femininity, on the one hand, and effeminate or passive masculinity, on the other.63 The Gypsy in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is a man—Edward Rochester, of course—masquerading as a woman. With a face “all brown and black” and “elf-locks” bristling from beneath a bonnet, the disguised Rochester quizzes a skeptical Jane and perplexes her with an appearance alien but familiar, female but male.64 In this guise, Rochester resembles the outsize Bertha, another demonic woman with masculine proportions and strength. Like the dazed Harry Bertram recovering the memory of his identity, Jane responds to the hybrid fortune-teller in a state of disorientation: “Where was I? Did I wake or sleep? Had I been dreaming? Did I dream still?”65 Calling the Gypsy fortune-teller “mother” and unable to distinguish between dream and reality, Jane replays, if only briefly, aspects of Bertram’s relationship to Meg Merrilies. The heroine of George Eliot’s The Spanish Gypsy appears at the conclusion of the dramatic poem in men’s clothing: turbaned, like Meg, and dressed in the manner of her chieftain father, whose mantle as leader of her people she has inherited. And Wordsworth, in his poem “Beggars,” evokes the great stature of his Gypsy beggar woman with the opening line: “She had a tall man’s height or more.”66 All these characters are in the tradition of the large Gypsy woman, much like Jean Gordon, the prototype for Meg Merrilies, and all combine qualities of mother and leader. They seem to displace and then absorb the fatherly role and join male and female properties in the figure of a genderless primal ancestor.

In the next few decades of the nineteenth century, ancestral associations came to dominate literary and cultural representations of Gypsies, as a result not only of Walter Scott’s influence, but also of a general cultural preoccupation with the origin of the Gypsies themselves, with broader questions of vexed individual and collective identities, and with the need to imagine alternative lineages. The anxiety that was both expressed and allayed in stories of Gypsy kidnappings was transmuted into the very material of bildung in Guy Mannering and into a parable about remembering and embracing ancient ways. Scott responded to the fascination with the long and widespread presence of the Gypsies in Europe by making them into an emblem of a necessary, deep, and fundamental past. But Scott’s Gypsies do not simply represent a static and mystical moment in a distant time. They are subject to history, and they change in an ongoing process of intercourse with those whose lands and imaginations they inhabit. He gives them a political identity by inserting them into a historical situation—the “Clearances”—that did not necessarily involve them and figures them as the objects of legal harassment and persecution.67 Finally, by representing them as a “mingled race,” Scott raises at least the possibility that the hybrid pedigree of the Gypsies is mirrored among the settled and dominant peoples of the nation. Harry Bertram himself incorporates symbolic and affective elements of a Gypsy lineage, and the lairdship he cultivates will scatter but nonetheless preserve the memory of the Gypsies of Ellangowan. In Scott’s vision, the old ways will ultimately be transcended but not erased, and the Gypsies, far from being wholly separate, a nation distinct from Britain or Scotland, will be understood to have mingled with dominant cultures and even, perhaps, to have been their progenitor.