Give It Away

or How War Horse Helped Others and Why We Do What We Do

One of the most rewarding things about success is when you get the chance to share it. Mounting any theatrical production is a risk and there’s no formula that will produce you a commercial hit time and time again – there have been enough big-money flops to teach the producers of the world that. There must be some element of surprise when everything comes together to make a show not just a huge success, but one that keeps running, and none more so than War Horse. The creative team behind the show make no bones about the fact that when it came to opening night at The National Theatre in 2007 there was every chance that it was going to be one of the more expensive failures that they had staged. The point about arts and culture being supported with public money is so that a company like the National can take risks and mount productions that other theatres wouldn’t ever be able to even consider. It’s not that public funding allows you to produce shows that don’t need to make their money back – arts funding isn’t there to foster a lazy theatre – but if War Horse had run in its allotted slot, sold merely OK and then finished, it probably would have cost more to do than it made back but it wouldn’t have sunk the theatre. That’s what a National Theatre should do; stage a wide range of work that appeals to different groups and balance commercial and artistic concerns.

Nicholas Hytner writes brilliantly about the Balancing Acts of those two concerns in his theatrical memoir of the same name, in which he looks at his tenure at the National Theatre which happened to be a period of unparalleled success in both areas. The fact that War Horse went on to become the most successful show the theatre has ever produced is not just a happy piece of luck, it is because of the very fact that it could have been a massive failure. Another show that made waves both here and across the Atlantic was the RSC’s production of Matilda which, yet again, couldn’t have been made without ‘the seedcorn funding provided by public investment’. A theatre that can take risks can take the occasional failure and sometimes succeed spectacularly, and the huge importance of War Horse’s success is something that goes way beyond impressive ticket sales and movie adaptations. It is something that affects the cultural life of this country now and for years to come.

I’m writing this sentence during a time of austerity, of huge budget cuts in public spending which have cut straight through the arts once again, with some councils choosing to reduce their arts budgets by as much as 100%. I mention the time of writing just in case you happen to be reading this during a time of economic prosperity and huge public investment in the arts (we may be entering the realms of fiction here) but I’m pretty confident that whatever the year happens to be, theatres across the country will be struggling to raise the money required to keep producing the kind of work that makes this country’s artistic output so revered around the world.

Public funding of the arts isn’t about supporting theatres because they can’t make enough money to pay their own way. It’s about supporting them to take risks or to put on productions that aren’t simply commercial guarantees because that is what helps maintain a rich cultural life, or allows a theatre to engage its local community, or to train or inspire the next generation of artists. But if all that sounds a bit airy-fairy then let’s look at some very basic economic facts: it used to be said that for every one pound invested in the arts you would get at least two pounds back. That is staggering. Not many other ‘industries’ can promise you that kind of return and that was the conservative estimate; some local councils saw something more like four to six pounds generated for the national economy with each pound invested. The latest independent report, however, states that for every one pound of public subsidy the Arts sector returns seven pounds to the country’s GDP. If you’re going to ask the Arts to justify public funding on a purely economic basis then I believe that’s case closed. If you’re trying to stimulate growth, spending, or whatever it takes to get the economy moving again then I’d suggest the arts are something you should be investing in rather than cutting to the bone. If you do, then you allow it to grow, thrive and take risks. If you do that then something like War Horse can happen again.

That’s enough soapboxing; the last thing I want to do here is engage in political speech-making, but I hope you can see that a show like War Horse was only possible in the first place because the National Theatre is funded by you, the taxpayer. When it went on to become a huge success, those that were part of it did several things to share that success with as many people as possible. Some of those were grand things, like the National’s support of other theatres, some of them very small but there was a generosity of spirit behind them all that feels very good indeed.

For Tommy

Just a month before I began rehearsals at the New London Theatre a man called Harry Patch passed away at the extraordinary age of 111. Towards the end of his life Harry was known as The Last Fighting Tommy, being the final surviving man to have fought in the trenches of the Great War. For much of his life, along with many other men who had fought in similar battles, he had refused to talk about his experiences but, perhaps sensing the importance of his position as the number of people who could give voice to that experience dwindled, he broke his silence in 1998 and took part in a series of interviews on radio and TV as well as writing his own autobiography, The Last Fighting Tommy. It is still possible to read that book and listen to his words in archived recordings but his death certainly marked a significant passing. There is now no one alive who can tell you face-to-face what it was like to fight in the trenches, to be involved in such a devastating slaughter, and with that significant milestone it’s difficult not to see an increase in the importance of telling stories like those in War Horse.

As a company we always felt proud to play our part in keeping those memories alive – ‘lest we forget’ – but it inevitably took on an even greater significance as we approached Armistice Day. The acting company was always keen to support the Poppy Appeal of the Royal British Legion each year. Any cast royalties from sales of the CD of the Original Cast Recording have been donated to their work and each year in the fortnight leading up to Remembrance Sunday we took the opportunity to collect donations on their behalf. A quick speech during the curtain call to explain the importance of their work (and not many people can believe that an actor who is as happy as can be when prancing about the stage performing in a play can be reduced to a dry-mouthed, quivering wreck by the prospect of uttering a few sentences on stage as ‘himself’ – public speaking is terrifying!) and then members of the company would hotfoot it from the stage to the areas front of house with buckets to collect anything that audience members felt able to give. What never ceased to amaze us was the generosity of theatregoers year after year, even when times were tough, even at the end of a not-inexpensive night out. There’s an old joke you can put in your pre-collection speech about how those buckets can get very heavy with all that loose change but you can always make it easier for the cast by remembering that folding money is considerably lighter but, jokes aside, there were always many notes in those buckets at the end of the night and it always felt very good when that cheque, measured in thousands, was sent off to the Royal British Legion.

We never wanted to exploit a captive audience but one other campaign that is supported by theatres across the West End, and indeed around the country, is something called Acting For Others. Actors are in the habit of lending their names, time and heartstring-tugging voice-overs to various appeals but they also like to care for their own. I began this chapter by mentioning the importance of sharing good fortune, and for every successful actor there are hundreds more who are much less fortunate. The Combined Theatrical Charities were brought together by Laurence Olivier, Noël Coward and Richard Attenborough back in the 1960s and is made up of a variety of charities that help actors and those that work behind the scenes who find themselves in need. They might be disabled, suffering from illness, or caring for children who have specific needs and for one week each year we collect on their behalf, again amazed at the generosity of our audiences.

All About the Books

I liked the idea of giving something back to audiences as well and that is why for the first two years of its life I decided to take part in World Book Night. The brainchild of energetic publisher Jamie Byng, WBN began with a simple and bold aim: to give away one million books on a single night and help promote reading. A list of twenty-five books was drawn up and I spotted early on that one of them was the seminal war novel All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque. (If it’s taken until this page for you to get the pun in this book’s title then… I don’t know what to say). This provided not only a great opportunity to be a part of WBN’s noble aims but also to finally fill an obvious hole in my own reading because I hadn’t yet read this classic. After some negotiation I was given permission to distribute my allotted copies of Remarque’s novel to an unsuspecting audience at the close of the show. I hoped it wouldn’t cause some kind of literary riot.

As we came towards the end of the company bow on the evening of the inaugural World Book Night my heart began to hammer violently, all moisture in my mouth seemed to be diverted to the sweat on my brow and I made my little speech about WBN, Remarque and how with only forty-five copies to give away and over a thousand people out there it would be great if only those very serious about reading the book would take a copy. The books had been placed at the exits and I’m pleased to report that the dutiful front-of-house staff weren’t mauled by a riotous mob, they only had to deal with a few disappointed punters who got to those exit doors too late (although, as I pointed out, the book is of course available at all good bookshops and even for free at your local library). It was even harder the following year when each giver was only allocated twenty-five books to give away. Luckily there was a criterion: that the books be given to people who weren’t regular readers. My choice that year was The Road by Cormac McCarthy which I won’t go into any detail about here but suffice to say that if War Horse has high stakes and All Quiet… is unflinching then The Road goes even further than both and thus reduced its potential audience even further.

I love pressing a copy of a loved book into a friend’s hand (although there then follows the trepidation whilst you wait for their response. What if they don’t love it just as much as you do? What if, God forbid, they don’t like it at all?!) and it really was special to be able to give away several copies of those two classic novels to some unsuspecting strangers on those two evenings. We’re back to sharing again but that really is one of the great pleasures of literature, sharing your passion for a book with someone else. I mean it when I mention pressing a book into someone’s hand, I actually mean pressing it into their hand, curling their fingers around it and saying, either with words or just your eyes, ‘I love this and I’m giving it to you’.

Shortly before starting War Horse I had decided to begin a book blog online. This had come about after I had done that very thing of pressing a book into someone’s hands; in this case my wife’s. The book was a favourite of mine, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon. When she was about halfway through the book I asked where she was up to. ‘Oh, he’s just in Antarctica with his dog.’ I was flummoxed. I couldn’t remember Antarctica. I could barely remember a dog. And I realised that despite the fact that I considered myself ‘a reader’ and got through at least a book a week at the time, I wasn’t retaining nearly enough of them, even of the ones I loved. This is the peril of being a reader of many books; it simply isn’t possible to retain detailed knowledge of them all – or at least my brain isn’t wired that way (part of this may be due to my actor’s brain which was used to learning lines quickly but losing them just as quickly again once they became surplus to requirements).

So I figured that if I committed myself to writing a detailed review of every book I read, then not only would I read them more closely, making notes as I went along and marking down memorable passages, but at the very least I would have an online record of my thoughts that I could always refer back to if necessary. And of course writing my book blog was a way of communicating my passion for books to a wider audience – but I had no idea how it would develop when I first began it, nor that I would still be doing it over five years later (sounds a bit like War Horse). The online book community was really beginning to make waves back then. I could see book lovers like myself were being taken seriously by publishers, their reviews sometimes even making it onto the books themselves and some prominent book bloggers were being published by newspapers and courted by book awards. But at that early stage it was all about discovery for me. Contact with publishers meant that I was up to speed with the new books being published and there was the thrill of receiving early reading copies which is something I don’t think I will ever tire of. But the conversations in the comment sections of each other’s blogs was increasingly filled with some of the best book recommendations I’ve ever had. Out-of-print classics, neglected masterpieces, whole oeuvres hidden from most bookshop shelves – it was a treasure trove of other people’s reading experience.

I was inundated with so many books by publicists and authors that I couldn’t possibly hope to read them all unless reading was the only thing I did all day. (Now there’s an idea.) But just because a particular book wasn’t my kind of thing or I couldn’t find the time to read it, didn’t mean that it should languish on a charity shop shelf. There was already something of an internal library in the green room of the New London when I arrived but let’s just say that it grew ever so slightly once I got involved, regularly replenished with new books as they arrived from publishers, so that they might find the right readers to help spread the word about them.

What It’s All Aboot?

I’ve mentioned the work War Horse has done for other charities and also how actors like to look after their own. There was one way in which we did this on a far more personal level. Cast your mind back to the concept of Thursday Treats as mentioned in the chapter ‘Meeting Ginny on the Stairs’. Well, there was one event that was organised in secret, or at least as a secret from one member of the company. Derek hails from Canada and he first joined the company when he came in to provide cover for one of the horse puppeteers after narrowly missing out on getting the job himself. He was an exemplary company member, picked up the job incredibly quickly and performed brilliantly in the Hind role. Derek eventually became a fully fledged member of the company and we were all saddened to hear one day of the fact that his mother was very ill and about to undergo some experimental and very expensive treatment back home.

So we decided to have a Canada Day in between shows one Thursday, a celebration of all things Canadian; costumes and food, the usual deal. This time, however, people would make sweets, cakes and desserts and charge for them so that we could raise some money for Derek’s mother. We had people dressed as hockey players, flags, lumberjacks and even a moose; we had waffles, pancakes, special cookies and Timothy Horton’s Hot Chocolate. It was a huge effort made by the entire building and it was clear how much it was appreciated by the man himself. But it was some time afterwards that we realised the import of what we had done when Derek read out a letter from his mother to the company in which she thanked us for what we had done for him and for her and what a great comfort it was for her to know that whilst he was away from Canada and working in London he was with such a supportive and kind group of people who were clearly taking good care of her son. And what mother doesn’t want that?

Perhaps it was because it was a handwritten letter, a rare enough occurrence even then, or perhaps that we simply didn’t expect it, but it was incredibly moving to hear those words and to realise that some of the very silly ways in which we kept ourselves amused were the very ways in which we bonded ourselves together. Agatha Christie once said that ‘It is only when you see people looking ridiculous that you realise just how much you love them.’ Derek had been ridiculous on more than one occasion and we knew very much that we loved him. Hopefully, as we stood around dressed as Canadian stereotypes, he felt the same way. There was certainly nothing but love in our desire to act together for someone else, someone we had never even met.

Doctor Rycroft

If I asked you to picture the mirror in an actor’s dressing room I bet I could guess the kind of image that would pop into your mind. A clean, reflective rectangle surrounded by light bulbs, possibly a few good luck cards? Maybe even some wilted blooms in the reflection? It is the one bit of the theatre we can truly call our own and so you’d likely find plenty more adorning that space: newspaper headlines or articles, photographs, drawings by loved ones, sweet wrappers, postcards, and things far more esoteric. And despite the regular health and safety inspections which tend to cull these areas of too much decoration, particularly if it dangles anywhere near enough the light bulbs to create a potentially hazardous fire risk (despite the fact that nowadays the bulbs tend to be of the energy-saving variety and therefore not capable of reaching the skin-blistering, fire-starting temperatures of their ancestors), you can’t stop the unique way each actor will choose to embellish theirs.

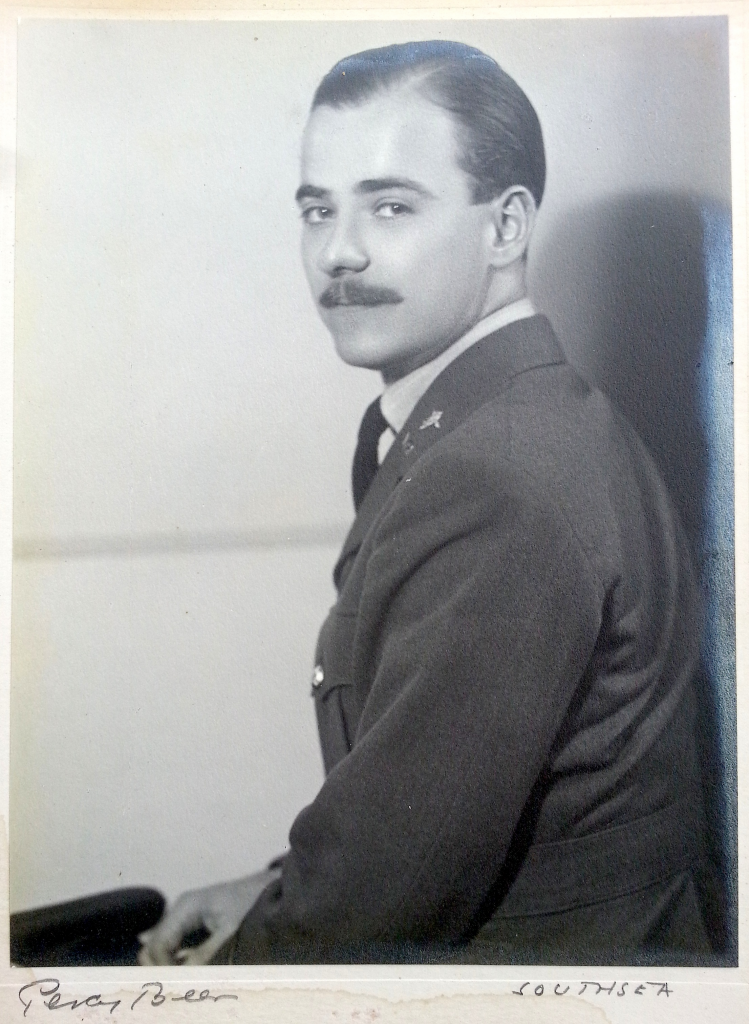

Photographs of family are commonplace but because War Horse is a period piece set during the time of the Great War you would have found photographs stretching back decades rather than years around some mirrors at the New London. On doing their research for the play, some actors discovered that a member of their own family had a connection to horses during that war, or the cavalry, or the yeomanry. They found out more about what their family were up to at the time if they weren’t directly linked to the conflict. Others found military links in their family from other wars and found that gave them a connection of sorts. I had a photograph of my grandfather on the mirror for that very reason.

I knew that my grandfather had been a doctor during the Second World War and, more than that, had been present with the American troops during the horror of the Normandy landings, acting with a courage that earned him the Military Cross. He never spoke about his experiences there, not to my father, not to me; not to anyone as far as I know. He did keep a diary, however, which my father spent some time transcribing after my grandfather had passed away. It doesn’t give much away from an emotional point of view. Here for example is the entry from 6th June 1944, the day of the Normandy landings themselves:

Awake 7.30. Up and about 8.0. French coast in sight. Seemed about 10 miles away. Tidied packs etc. Would it be as rough as I expected? Nearly landed at 11.30. Not a sign on the beach. Suspected a trap. Wandering around during rest of morning and early afternoon. No food provided. Anxious looking people. Reading ‘Kings Row’ in lorry cabin just before we set course. Keeping well down in cabin ‘in case’. Still no trouble. Ship next to us touches down too far out. Jeeps fail to make it. Abandoned. Another Landing Craft, Tank crashes into back. Occasional shell on beach. All I expected. We do good landing. Blocked very soon. Lie on sand near L.C.T. trap. Abandoned rifle nearby. No casualties seen. Bombardment commences after ten minutes. Not taken seriously at first. Odd gun probably not spotted. Hole in shingle would be ‘safe as houses’. Quickly disillusioned. American wounded too. Dashing about everywhere with panniers. ‘Only a matter of time’. No plan. No exit. Duggie killed next to me under lorry. Miraculous escape. Shell hole wounded. Very hard to get help. Tide coming up. Village safe. Sure to be shelled during night. Bomb near water – dirt everywhere. Felt it to be last night on earth. Dreaded morning. Working all night at first aid.

What you can’t tell from that entry is that he was the only medical officer on this sector of the beach that night, and that he did all this whilst also being wounded himself. As the announcement of his Military Cross in the London Gazette said, ‘He set an example of great courage and devotion to duty and was responsible for saving many lives.’

I remembered very clearly from my childhood seeing a photograph of him in his military uniform and I later learned that this portrait was taken to commemorate the awarding of his medal. I wanted to have a copy of that photograph, firstly because I was proud of his achievement, but also because it felt like a way that I could make a more serious connection to what I did in the play, the character I had to inhabit and the experiences he had to go through.

As I’ve said before, acting is just dressing up and talking in silly voices – and coming from a family with strong medical links (both parents and grandfather) and Cambridge history (father and grandfather) I did feel like a bit of a let-down for not following the more academic career I could, and probably should, have done. The closest the Rycrofts were going to get to another doctor in the family was me appearing as one in Casualty on the BBC. My sister followed a far more academic path and indeed she is a doctor. Of philosophy. I don’t know how good she is with first aid but if I was looking for a first responder I’m not sure her aforementioned in-depth knowledge of the cultural significance of facial hair would be much use in staunching a wound or saving me from choking on an interval treat.

Performing in a play where you act out a cavalry charge on a puppet horse it would be easy to get carried away with the fun of it; to enjoy bellowing out the word ‘CHAAAAAAAARGE’ and wielding the cavalry sabre, but not so easy to imagine what it was actually like to have done so in 1914. How do you even begin to imagine such a specific event from a hundred years ago when it is so far removed from the experience of even a modern soldier, let alone a cosseted, middle class actor? So you draw on whatever you can to make it real. I had ridden a real horse, for starters, but I also remembered riding with a group of horses many years ago and their communal excitement when they all started cantering together. I would try and imagine a much longer line of men on horses than we could actually stage, imagine the sound the horses would make as they gallop, the hooves on the earth, the breath coming in loud snorts, the jangle of bridle and reins, scabbard and spurs, the excitement of the horses as they finally got the chance to open up and run together; and then, cutting through all that, the decimating impact of machine gun fire on both man and horse. And here I have to think of my grandfather, and of the scenes now made famous by Spielberg in his film Saving Private Ryan, the way those powerful machine guns cut through man after man, leaving them no chance, wave after wave cut down and only the lucky few pressing on. To try and connect to the seriousness of war when you live in a time of non-conscription and with no experience of much violence at all in your life is a genuine conundrum. That’s why I wanted to have that picture to hand, to remind myself that someone in my family saw horror like that, saw things so awful he wouldn’t be able to talk about them to anyone for the rest of his life, and that whilst the uniform may look similar and our faces too, of course, once I applied that moustache (that looked so hilariously like his, quite by chance), I was a world away from his experience and I had to try and do it justice.

Family

So many of us did what we did with family in mind. Placing a photograph of a family member from the past on a mirror highlights the way in which to a certain extent we aim to be as successful as we can in order to fulfil the wishes our parents had for us and their parents before them. The aim is always upwards, to make our children’s lives better in the ways our own weren’t – the parent who never had much growing up wants their child to have everything, the parent who wasn’t allowed to follow their dream wants their own children to have total freedom to pursue theirs. Of course that can create new problems, but there’s no perfect way of doing things.

The most immediate way in which War Horse helped people naturally was that it employed people, lots of them, and offered a kind of security that actors just aren’t used to. Even just doing one of the shorter contracts and then leaving meant six months of solid work, a positive boon for an actor, especially in a climate of austerity. But for those who fulfilled several contracts, whose employment reached out into years rather than months, the effect of steady employment may actually have been life-changing. I don’t mean anyone on stage was getting rich. This may have been the West End and you may have heard stories of people getting paid bazillions every week, but this was the National Theatre in the West End so wages were pegged well below that. (I do remember, when a friend from dance school left the sixth form to join the company of Cats that he returned to visit and told us that the lyric, ‘The Rum Tum Tugger is a curious cat’ had been adapted by the underpaid ensemble into ‘The Rum Tum Tugger’s on a grand and a half.’ This being the early 1990s, that sounded like a weekly wage of epic proportions to me. Apparently it works out as about £2.5k in today’s money.) The effects of regular income can actually be far more creative than purely financial. The actor saddled with debt and student loan repayments can make completely different life choices once those debts have been paid off. The actor with plans and ideas for other projects might actually be able to fulfil them when he has job security for a while and is even more likely to when in contact with the network of other creative types that came with a job like this.

Anyone who knows where the pay cheque will be coming from for any set length of time can direct their energies into something other than the need for the next pay cheque, something more creative. Or concentrate more on their life outside of work, to make a life. Most people have fairly humble desires for their lives, I think: they want to fall in love, get married, have a home, make a family; and yet it seems harder and harder to satisfy some of these simple things. I’ll say more about babies in the following chapter but it was no coincidence that so many of the various cast members of War Horse over the years used their time there to finally make something happen. Marriage, honeymoon, birth, travel, writing, creating, house-buying, home-improving, even a career change have all been made possible. And the effects of that employment weren’t restricted to the person in the show. The actor turned breadwinner can free up their partner, or even another family member or friend. The success of the show can spread outwards like ripples in a pond.

There’s a reason why this book has the dedication it has, because every day of the four and half years I spent doing War Horse was in order to provide for my family in one way or another. Anybody’s life is going to change over a period of time like that but there was something distinctly transformative about that period for me, and for us as a family. Performing in a play also means, in theory, that you have time during the day to spend with that family, to actually raise your own children, to play an active part in your family as well as working to provide for them. I say in theory because there are huge parts of the year that are taken up by the re-rehearsal process and that means that you don’t get to see them as much as you might like, or indeed at all. And that’s why it’s so important not to take anything, or anyone, for granted.

I’m not going to even begin to uphold the myth of the family provider, especially in this day and age: most families I know don’t consist of a breadwinner and a homemaker, they’re made up of two parents frantically juggling work, childcare, clubs, classes and social lives in a frenzy of diaries, calendars, scribbled notes and frantic text messaging. Even at our most 1950s I knew that every day I walked out of the door to ‘work’ it was someone else who was doing the actual work at home. When you can’t be there to change nappies, wash clothes, cook, clean, manage finances, fill in forms, entertain, or any of the other myriad tasks that must be completed to have a family, it is very easy to watch them all just happen, to pull milk from the fridge for your morning cuppa, to see a boy suddenly stand there in new school uniform and wish you all the best for your day at work. Or it is if you happen to be married to my wife. Don’t worry, this isn’t about to get all horribly gooey, but indulge me a small moment.

We all know the old adage about what – or rather, who – lies behind every great man, but we would do well to remind ourselves of the meaning behind the cliché. The man is only able to become great because of the support of the person beside him but you don’t have to be a great man, or a man at all, to benefit from the support of your partner at home. Every demand made on a person who works is a demand made on their partner too, as they are the one left to deal with the consequences. A rehearsal period that means working through the days and nights of three months was always a tough ask for those of us who stayed on from one company to the next but for those of us with wives/partners and children at home that also meant three months for them to function essentially as single parents. If I walk out of the door in the morning and don’t return until after everyone is safely tucked up in bed then that’s a long day for everyone, not just me. I will forever be grateful for every bit of support that even made it possible for me to go out and work every day of my time at War Horse. I had the easy job.