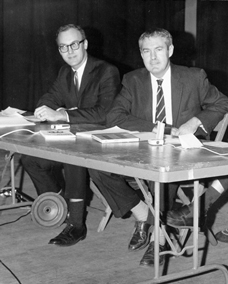

Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary present early psychological findings on psilocybin

RAM DASS REMEMBERS TIM

AN INTERVIEW WITH RAM DASS BY ROBERT FORTE AND NINA GRABOI

RF: When we approached you about contributing to Timothy’s memorial volume you said, “That will be hard.” Why so hard?

RD: Because Tim is one of the more complex human beings that I have met in this lifetime, and my reactions to him are very complex. So to articulate it in a coherent and integrated fashion isn’t easy. That’s really what I meant; that sometimes relationships are so subtle and nonconceptual, and that’s what the relationship between me and Tim is like. It’s not easy to articulate because there’s love and there’s respect and there’s judgment and there’s frustration and there’s disappointment and there’s, you know, great appreciation, and all kinds of qualities.

RF: Timothy has affected millions of people in a profound way, but probably no one was as close to him during those years at Harvard as you were. I wonder if your relationship typified the massive changes that would follow collectively?

RD: I doubt it. His and my interaction was a product of our collective neuroses. Mine are pretty pronounced and they certainly were in those days. I’m hardly Johnny Q. Citizen in the sense of representing a reaction that would be common to other people. We were locked in some incredibly intense psychodynamics of really archetypal and mythic proportions. And I don’t know that I was the “closest.” We sure spent a lot of time together, and we were very close, but Tim is in a way equally close to everybody. Tim may spend more time with a person, but I think people who are close to him feel that he’s not that close, or he’s not close in that way. I think we expect people to be close psychodynamically, and he’s not really interested in that plane of consciousness.

Richard Alpert and Timothy Leary present early psychological findings on psilocybin

RF: What plane of consciousness is he interested in?

RD: Timothy is somebody who really honors the Truth, the essence—I mean metaphysical truth, as well as psychological and social truth—and who is a scientist in the deep sense of being a scientist. He is interested in understanding the universe in some kind of systematic way. He’s quite a scholar. He reads a lot, but then it all gets filtered through this kind of charming stuff, this play of mind that seems to take away from the depth, the power of his mind, the power that I knew when I was with him.

NG: Was the role of spiritual revolutionary authentic, or did his ego play a part?

RD: Well, it is hard to think of it as his ego. I’d say he’s more sociocentered than ego-centered. He’s a social role-player. I’m not sure that he has an ego in the sense of a thickly-centered self-concept. He just fulfills roles in a charming fashion.

NG: Why did he so deliberately provoke the establishment?

RD: Well, that’s another part of him. Timothy was the Irish fighting the English. He was the underdog fighting the establishment. That’s one of the major myths of Timothy’s life. There was no way to get along with the establishment with Timothy. Sooner or later he had to undercut whatever dynamic there was. I was always busy healing the rifts and keeping up in the establishment as much as I could. I couldn’t always do it but I would try; and Timothy was constantly undercutting that.

RF: One time I asked you about him and you said, “Timothy is a great man, but he has a problem with authority.” And I thought this is exactly why he was a great man, because authoritarianism is a very great problem.

RD: I don’t question that the mosaic of his personality contributed deeply to the role he plays in society. It was all necessary. So the antiauthority part of his mind would question what the psychiatrists said about LSD, while I—coming from a nice Jewish middle-class conforming family—thought if the psychiatrist said it, it must be so. Timothy opened my eyes to questioning those kinds of authorities. I had been trained never to question them.

RF: This is again one of his mythic roles.

RD: It’s a role, you know, but look at what power he had. He was the only one on the scene that I saw who acted that way. Frank Barron also had the experience, but he wasn’t ready to blow the whistle on society. Timothy wanted freedom of consciousness, and that’s basically a social, political position.

RF: Freedom of consciousness? How do you mean that?

RD: Freedom from being controlled by others, by a social system. In other words, we have a right to the freedom of how we use our own consciousness. And he felt that was one of the freedoms.

RF: You mean that not just in terms of drug laws. There’s an unconscious manipulation of our minds by the establishment, and we have a right to be free from that.

RD: Exactly. It’s not necessarily conscious on the part of the establishment. The establishment is conned by it also. There’s a conspiracy to define reality conceptually a certain way, and freedom is to get free of that, and that’s what Buddhism is about, getting free of those conceptual traps of mind. So we were talking about something very deep, which is the freedom of human consciousness. Tim was seeing the relation between that spiritual or altered state of consciousness and the sociopolitical situation. He wanted freedom for the method of getting high, not just freedom for the state of consciousness. And that gets into the question of who controls the method.

RF: And this is a conversation that you have pretty much stayed out of. You didn’t want to discuss the political questions.

RD: Well, first of all, in those days, Timothy was politically more sophisticated than I, much, much more. I was psychodynamic, so when I had the psilocybin experience I started to work with it from two levels: one, the opening to the mystical end of it, and two, the redefinition of the meaning of psychodynamics, of personality. That fascinated me and seemed like the place to go. Timothy was much more interested in the social political aspects. I wasn’t avoiding it. I remember I was in India and I got all these clippings from Allen Ginsberg who was at the Democratic convention, being hit over the head and all of that. It was ’67. I sat there in the temple thinking, “He’s on the front line. He’s saying ‘this is what I believe’ and he’s confronting it. And look at me, I’m copping out. I’m hiding back in here in the temple.” Then I thought, “But what am I doing in this temple? I’m spending fifteen hours a day examining my own mind. Isn’t that a leading edge too?”

RF: Do you think Timothy’s identifying the drugs with the counterculture made the mystical pursuits, the scientific mystical pursuits, more difficult? Professional psychedelic researchers today regard his behavior as a problem because he antagonized everyone, polarized society, and the drugs are now forbidden.

RD: Well, there was no way that wasn’t going to happen. Almost at the same time we were getting outrageous, Ken Kesey was having the acid tests in San Jose, L.A., and places like that. The San Jose News ran headlines this big, “Drug Orgy in San Jose.” There was no way this wasn’t going to become a very hot political issue very quickly. We might have had another six months or a year of grace to get a little more established. We could have done it more politically and coolly, no doubt. Aldous was down on Tim for that, and a lot of other people were too. But my sense is that Tim was so far out of the experimental models that were accessible; he was more into the collection of data from musicians, artists, writers, using it as a natural medium, you know, all that stuff. It was not easy to do naturalistic research in a behaviorist society. I thought we could have played with the university and gone on and on, because there was a tremendous amount of desire on the part of the university to give their academes liberal academic freedom, as long as it didn’t scare the university.

RF: I envisioned this book to be kind of a response to a book that came out recently in England, the proceedings of a symposium held in honor of LSD’s fiftieth birthday by Sandoz and the Swiss Academy of Medicine. The president of the Swiss Academy began the conference by praising the scientific possibilities of LSD, and then he said, “But unfortunately LSD did not remain in the scientific scene. It fell into the hands of esoterics and hippies and was used in an uncontrolled way.” It can be argued that the esoterics and hippies made the most of the stuff, more than the scientific methods of that time were going to. Still “science” fumbles around for a way to understand these drugs. Tim thought early on that the drugs needed to be freed from the laboratory if they were going to do any good. He answered the important questions, demonstrated “set and setting,” and shared his results—in an exuberant way, to be sure, but it may have been irresponsible not to.

RD: I think what happened with psychedelics in the early ’60s so profoundly altered this society that it is still just beginning to grow into what’s happened to it. It was a mushroom and it did explode, and it was carried through the hippies, through the minstrels, through the rock and roll movement; it was carried into the collective consciousness and it has mainstreamed in collective consciousness, and it has to do with the relative nature of reality. And that’s a big, deep thing and it happened to this society.

RF: It’s amazing it still hasn’t dawned on society what these drugs really are.

RD: No, it hasn’t. And that’s kind of fascinating and kind of beautiful. Because it’s very scary to people who have a vested interest in a reality being absolute.

RF: How do you feel about getting tossed out of Harvard?

RD: I look at being thrown out of Harvard as an incredible gift. The basic thing that happened to me at that moment with the mushrooms was for the first time probably since I was two years old that I listened to myself from inside; I used my inner criteria to validate my existence rather than external criteria. That was a major shift.

RF: This was a renaissance for a lot of people.

RD: I have a feeling it was. . . . Once I get over the fear of the outcome I can really look at things as they are and delight in the edge of chaos quality that’s happening when a transformative process is going on in a society. It’s really scary because it undercuts control of the situation.

RF: Fear of the outcome?

RD: The fear of whether society blows itself up. The big fear is that the psychedelic revolution or evolution gets crushed back into stupidity and ignorance.

RF: The Hindu cosmology looks at the world in terms of these grand cycles and it’s almost a cliche that we’re in the dark period of a Kali yuga. Do you have a sense of that?

RD: I don’t live consciously in these mythic structures. I mean I can create an Armageddon one, an Aquarian Age one, a Kali yuga one that goes into either the Sat yuga or into the Pralaya, when everything dissolves back into nothing. They all seem perfectly reasonable to me. And I don’t really care, because it doesn’t make any difference to what I do . . . whatever scenario, I just have to quiet my mind, open my heart, and relieve suffering in the world around me. This is it. And I’ve come to kind of delight in this. The minute you say, “What does it mean?” you’re asking for a conceptual structure, a prison enclosing what can’t be imprisoned. So I don’t live in how it all comes out.

RF: Getting back to Timothy, he has shifted metaphors so many times in his career. You’ve probably heard him say that a third of what he said is bullshit, a third dead wrong, and a third home runs. That gives him a .333 batting average, high enough for the Hall of Fame. What’s the bullshit and what’s a home run?

RD: Well, it’s really hard to assess. Is his fight with the establishment, with authority, “bullshit,” or is it part of the process? I don’t look at it in terms of baseball, just in terms of process. Timothy uses metaphors; he’s not attached to metaphors, he moves in and out of them like snails inhabit shells; you know, you outgrow them and you just drop them. The metaphor served its purpose to take a quick fix on that which is not a concept. So I don’t know that I would think of them as his “bullshit.” I think of them as short-term; at that moment they serve some purpose and then you go on, and then you begin to see that it’s really the sum total, the gestalt, rather than any one of them.

RF: In Chaos and Cyberculture he says the main point was to induce chaos. It was all for pranks.

RD: Yeah, Timothy was a rascal. I was a rascal in training. I was too middle class to be a good rascal. Timothy was a rascal. And he did delight in chaos. But there were a couple of forces in Timothy. He kept incredible records. He kept file cabinets full of records. That isn’t chaos, that’s another quality in him that collected stuff and thought about it and structured it and so on. At the same time, he was socially always playing with the edge and then pushing the edge and pushing the edge and pushing the edge.

RF: It is usually a troubled relationship between mysticism and politics, between those trying to free themselves from the images others use to bind them.

RD: Timothy always said you’ll find the mystic and the visionary much closer to the prison cell and the priest class will be running things. He has a sense of history, a sense that though he might be seen as irrelevant now, two hundred years from now he will be seen as something else. The idea of “you leave no footprints” is a little too Zen for Timothy, I think. He has a sense of generations at a time.

NG: In recent years, perhaps since his imprisonment, his emphasis has been on the physical rather than the spiritual dimension. It almost looks as if he’s not spiritual any longer. What do you think?

RD: Well that isn’t true. He’s spiritual, but he’s not interested in these other planes of consciousness. I mean he’s interested in the use of the mind, of the intellect and its capacity and how far out you can push it. He loves conceptual play, and the question is, is he doing it from a nonconceptual space, which is purely spirit? He might be spiritually way beyond, in the sense of nonattachment to any myth or model of himself or anything else. The question is, where is Tim standing? Is there any place you can catch him? I feel a certain somebody in there that I don’t find with my guru, for example, and that somebody is where you’re standing. I know I’m standing somewhere, and I’m not sure I’d see him if he wasn’t standing anywhere, you know? So now I work in Tibetan Dzogchen, in realms of pure awareness that have no astral content at all, no dualism, no gods and goddesses, embracing the form into the formless constantly, enjoying the play of phenomena. That is a lot of what Timothy is. I never think of him as a Dzogchen master, but there is a way in which he does that. He does it without full compassion, perhaps, and that means he’s not fully empty. But he has a quality that is very spiritual.

RF: He is very present with you; he always seems to be paying close attention. Was he like that when you met him?

RD: I think Tim’s always had those qualities.

RF: He is very childlike. He doesn’t dwell in the past or the future, he seems totally immersed in the present moment.

RD: And this is what infuriates people who want continuity. Ghandi said, “My commitment must be to truth and not to consistency.”

NG: Timothy is so far ahead. He’s like a man from the future; his mind outraces everyone.

RD: Well, it’s a funny thing about the mind. There is a way in which the mind, no matter how hard it works, never gets there. The minute you realize that and surrender into being rather than knowing, you’ve just moved to the next level. Being far ahead is like a cul-de-sac in a certain way.

RF: It’s not just his mind. I’ve seen this quality of childlikeness, this enlightened quality in him, playing croquet in his yard as well as talking about metaphysical or scientific notions.

RD: We’ve had great, great fun together. Great fun. Like playing in the cosmos, like walking with giant steps and dancing huge dances. It was a play of just this vastness. Timothy invited me into those realms and I was thoroughly delighted. A lot of our acid trips together, a lot of our life together, was like that, Mexico and Millbrook and IFIF. It was just pouring out. I remember those Saturday nights by the fire in Millbrook with the family, with Maynard and Flo Ferguson and whoever else was around and Tim and me and Ralph and Susan and all of us in the dark with the fire flame lighting us and us just playing in the cosmos, just one mind and all these voices coming together. These were some of our finest moments. Then I went to India and was just absorbing as fast as I could. Then I had that gnostic intermediary role of bringing the Eastern metaphysics back and integrating it with Western psychology. I was wide open and I don’t think that’s ever stopped.

RF: Did Tim influence you going to the East?

RD: Well, Allen Ginsberg had gone, and Tim went and Ralph went, and so it was clear that that was the way to go because the manuals for understanding what the hell we were doing were coming from the East. Timothy played a role in the sense that he foreshadowed. What is quite extraordinary is that on Tim’s way back from Almora to Delhi the bus stopped at Kanchi, which is my home temple base—a little tiny temple on a very small road. A man, who later was my yoga teacher, got on the bus and sat next to Timothy. Timothy was very impressed with this guy, and when they got to Nanital, the guy got off the bus and started to walk away quickly. Timothy went to follow him. He was halfway across the square when the bus driver blew the horn. The bus was going on to Delhi, and Timothy turned and got back on the bus. If Timothy had followed him he would have met my guru, whom I met two years later by an entirely different route. Now if you can’t feel that there’s some fascinating game within that . . .

RF: Tim has said one of the things he’s sorry about is clearing the way for the gurus to come from the East.

RD: I think it should play out its story. I think that the Easterners weren’t prepared for the kind of seductiveness that they would meet in the West. A lot of them thought they were freer than they turned out to be. I mean that’s some of what Tim’s talking about. They brought a very deep wisdom, but they weren’t necessarily the representatives of those wisdoms, and the problem is that that makes the teaching not quite work. In other words, it’s not a clear transmission. They were able to pass on the information, but not make the full transmission. But there have been some remarkable people in the West. I mean Trungpa Rinpoche was no slouch and Kalu Rinpoche was no slouch. There have been a lot of people that were interesting but flawed in some way; that’s a maturing process for people. Allen Ginsberg brought over Bhaktivedanta, a Hindu. He did that before Tim even was into India.

I tasted of something that I have transmitted as faithfully as I could to millions of people who in turn have tasted something, and whatever that thing is, I feel that it is fine. It is a sense, a faith in the possibility of the liberation of the human being. And that’s very deep in me. It went from the mushrooms, through the grace of Timothy, to Neem Karoli Baba. Those two events define two stages of the journey. One, I realized I wasn’t who I thought I was, and I understood relativity, and when I met Maharaji, I met all the forms and nothing. I kept feeling there was nothing there and yet everything.

RF: That’s quite a statement, implying that we’re not free. This is the renaissance of spirituality. A recognition of our imprisonment?

RD: That’s pretty good. That’s Gurdjieff’s line, “The first thing: if you are ever to escape from prison, you must realize that you are in prison. If you think you’re free, no escape is possible.”

RF: Did you consider Tim to be a guru?

RD: Well, in India they make a distinction between Upagurus and Satgurus, and Upagurus are gurus along the way who open doors for you, but they may not be gurus in the sense of free beings. The difference between Timothy and Neem Karoli Baba was that Neem Karoli Baba, no matter how hard I tried I couldn’t find him. There wasn’t anywhere he was standing and there wasn’t anywhere he wasn’t. I had to deal with that reality with Neem Karoli Baba, and I didn’t have to deal with it with Timothy, so that’s the difference. But Timothy freed me from many planes that I was trapped in. He did a tremendous amount for me. He was very patient because I was extremely trapped in certain ways. He was certainly playing on a lot more planes than I was. But he was still somebody playing somewhere.

RF: You said when you first met him he was the most creative person you ever met. Did you mean creative as a scientific thinker, as a strategist, or as a researcher?

RD: Yes, as someone who can break set. That’s how I would define creativity.

RF: What about the numinous quality?

RD: Well, Timothy is charismatic, but charismatic isn’t numinous. I would say he’s charismatic, not numinous. His mind is extraordinary. He opened doors to other planes. I mean, all I had to do was get into relative reality. That’s what he did. He took me into a relative realty. And that was a major game, so he was a major teacher for me.

RF: Let’s look at “charisma.” Does it imply something negative?

RD: Well I don’t think that it should. It’s incredible, it’s like astral power. That’s what I think it is, you know. It really is a light, but it’s a kind of astral light. It’s not a spiritually free light; it’s intense, you know, brilliant people you call them, and you’re kind of awed by their brilliance. But it’s different than spiritual illumination. It’s like stars rather than the sun. Tim is like a comet that shoots across the sky. A lot of us are very beholden to him. I bet more people than is known are beholden to him.

RF: Still, there’s an element of trickery in Timothy’s play. . . .

RD: There are many rascals in the spiritual traditions, many rascals who use tricks to liberate people.

NG: I think there is much more to him than charisma. In the ’60s, the kids used to say they can feel his aura miles away. I remember a photo of him with a flower behind his ear . . .

RD: We’ve both got the same photograph in mind, at one of the Be-ins, I think. Well, he had the aura of youth, he was a stereotype of light and energy, and he had the aura of sexiness, and the aura of playing at the top of his game. Those are all the parts of what gave life to Timothy.

The question is, does the man make the moment, or does the moment make the man? Timothy wasn’t playing in a vacuum. He was playing with Alan Watts, Aldous Huxley, and Frank Barron and all of these really extraordinary people. Huston Smith, Walter Clark. It was a great scene; it was a web that was supporting a process going on.

I look at the cultural affluence, the information age, the social mobility, and psychedelics, and the awakening of ethnic consciousness and political consciousness. There was a moment when a lot of stuff was happening. And for anybody to try to grab it and say it was all due to psychedelics, or to affluence, the information age, or to the postindustrial mind or whatever, is too simplistic. I just see it as incredibly richly determined when a moment is profound enough to really shift a scene. The ’60s scared the hell out of the culture because they showed another potential exists for people. It provoked the reaction of the pendulum swing of twenty years of republicanism. That’s all part of these huge pendulum swings. Tim was on one end and Nancy Reagan was on the other.

RF: And now they are practically neighbors. Is there something imminent about to unfold comparable to LSD? Something that will stimulate us again, or more, or bring the earlier stimulation to fruition?

RD: I don’t know. Fusion would do it. We might just be creating the future with fusion instead of fission. Fusion would change the economy of the world. It would provide limitless energy, it would change everything.

RF: Possibilities like this have become conversations for millions of people because of Timothy and you.

RD: When you say “Timothy and you,” or something like that, you have to make a clear distinction. Timothy was a much more central player at that time. I was a neophyte, I was a student. We’d have parties in Los Angeles and I’d be sitting at the feet of Aldous Huxley and Gerald Heard as they dialogued about the enneagrams and the labyrinths in churches in Spain. I’d just sit there with these giant minds, and Timothy floated in and out of all this very comfortably and brought me into it. It was like riding a wave. It’s interesting about the waves. I realize that the excitement is in being in the little wave in front of the big wave. And that’s where Timothy and I were then, at that moment. That was exciting. It’s a place where society is basically putting you down or ignores you because you’re not even relevant. Then we got to the point where we were a threat. And then I got socialized. I’m almost a good guy again in the society.

RF: I’d like to read this book in a hundred years, or be in a room where Timothy was being remembered. Will the establishment succeed in trivializing his efforts?

RD: Well, I’m not terribly interested in historical remembrances. I think we played a part and that part transforms something and that transformation leads to the next transformation. It is just a tiny blip on the screen full of blips.

RF: Little blip, big awakening. These drugs have been hidden from the people for thousands of years. We don’t know how their reemergence will turn out, but this was one of the great moments in history.

RD: I think the seed is still in fruition. It is a much less homogeneous society, it is a more chaotic society, it is a more fertile condition for growth and change. It’s all doing fine.