Timothy Leary and the Psychedelic Movement

AN INTERVIEW WITH HUSTON SMITH

BY ROBERT FORTE

RF: Huston, it’s a pleasure to be in your beautiful home overlooking San Francisco Bay and hear your reminiscences about Tim. I’m hoping you’ll also speak more generally about the advent of psychedelics in modern life. Perhaps you can compare the styles of Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary. You worked closely with each of them.

HS: That’s true. I will do my best to speak to your questions.

RF: It may be a surprise to some readers that you have been intimately involved with this subject—psychedelics and religion—for over thirty-five years since your first experience in 1961. You’ve written over a dozen scholarly articles on the religious importance of psychedelic drugs, and devoted an appendix to the subject in your book Forgotten Truth. These writings are being compiled into a book by the Council on Spiritual Practices. Your most recent book, One Nation Under God, is about the victory for religious freedom won by the Native American Church. You are widely known as one of the most authoritative and eloquent voices on the religions of the world. You’ve worked for over thirty years to express the common vision of the world’s religions to revive a sense of the sacred in modern life. Yet in spite of your deserved stature you are still somewhat reticent to discuss this subject. Why is that?

HS: Because the psychedelics are so ambiguous. They are like a two-edged sword. They can cut through samsara to get to nirvana—which is to say, cut through the daze and doze of mindless existence and wake us up—while at the other extreme they can behead us. Just this week, in reading Peter Coyote’s first person account of the psychedelic sixties, Sleeping Where I Fall, I came upon his mention of one of the Haight-Ashbury’s Diggers who took acid on a bad day and became the three hundredth person to jump off the Golden Gate Bridge. The potential of these substances for both good and ill is so great that it is irresponsible to be glib about them. One should know one’s audience before one speaks.

RF: This is a subject that has been trampled in the war on drugs. Official sentiment against psychedelics was largely motivated by the ebullient antiauthoritarian spirit of the sixties and Timothy’s zeal certainly catalyzed that; or, perhaps the resistance had already been in place for centuries, and Leary’s efforts vaulted over that resistance to spread the word—like the I Ching says: when the wild geese find food, they call their friends. So what I’m hoping we can do today is talk about Timothy and what went on during that period, but also discuss the larger subject, the problems and prospects of integrating psychedelics or entheogens into modern society.

HS: You want me to plunge into that?

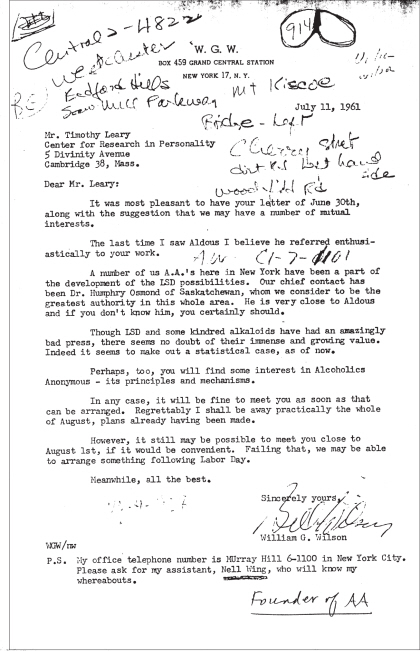

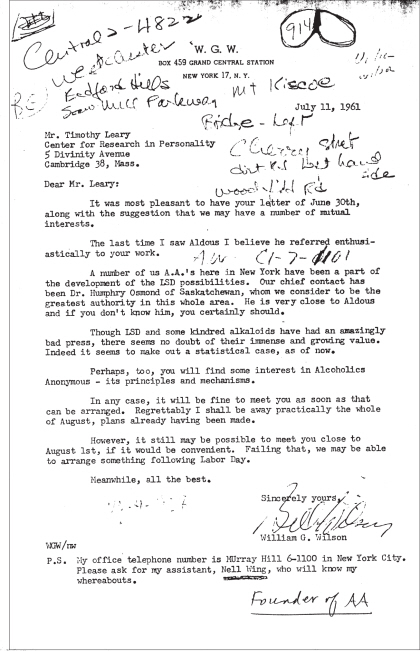

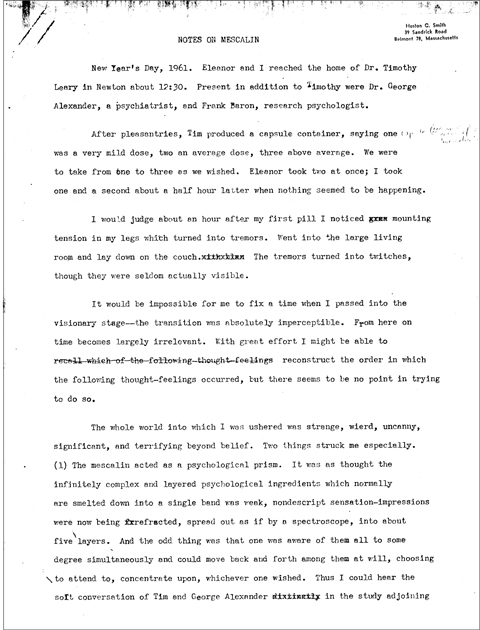

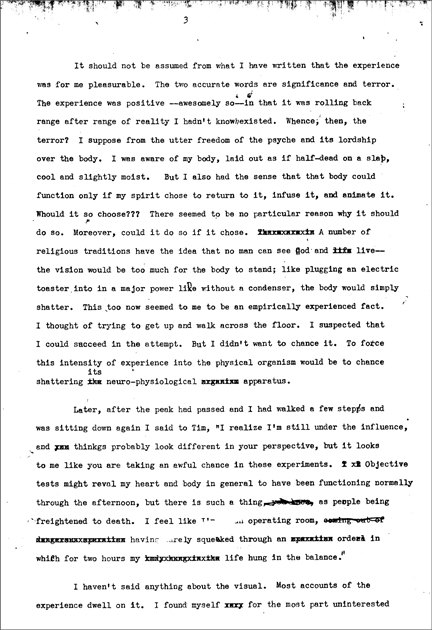

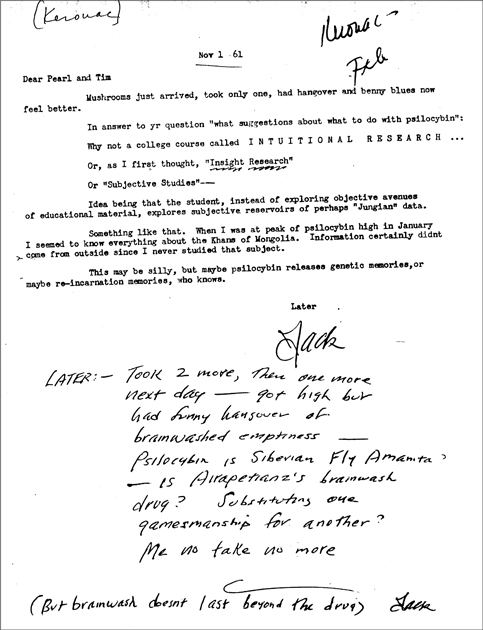

RF: I brought some documents with me that I found in the Leary archives to put you in the mood of those days, to help you remember the optimism, the intellectual and spiritual enthusiasm around those early openings of consciousness. Wonderful, passionate, excitement and interest from universities throughout the world, and from governments too. Here are just some of the letters from medical schools, divinity schools, prison wardens, the Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke, the National Institute of Health. Here’s a letter from William Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, written to Tim in 1961 praising LSD. Another from the distinguished psychiatrist Abram Hoffer in the Department of Public Health in Saskatchewan where they used LSD to treat patients citing “cures in alcoholics and addicts that are practically miraculous.”

HS: This is going to be an interesting book for me to read.

RF: Brilliant minds, some of the world’s leading scientists and artists, engaged in discovering these drugs and applying them to a whole range of things. Then the whole movement turned into chaos. Harvard and Sandoz chastise Leary and Alpert for being out of line, for seeking publicity more than science, then they’re fired. In just a few years Tim is sentenced to twenty to thirty years in prison, ostensibly for marijuana offenses. He’s denounced by Nixon as “the most dangerous man in the world.” Considering the source, that may be a compliment. Here’s a letter from a federal judge in Texas who sentenced Leary to twenty years saying he’d do it again and that he is unwilling to reduce the sentence, in spite of Leary’s having cooperated with authorities.

Did you have any idea of what was to come when you first became acquainted with the subject of sacred drugs?

HS: Before answering your question I want to take exception to your calling them “sacred drugs.” They have sacred possibilities, I’m not going to back down on that. But Aldous Huxley was wise in calling them “heaven and hell drugs,” and hell connotes what is demonic rather than sacred. We’re back with my point about their ambiguous character.

Now to your question: did I have any idea as to what was in store? Not at the start. As you noted, during the first year or two the mood was wildy optimistic, for all signals seemed to read green. You have touched on the important ones. Psychologically, the psychedelics promised easier access to repressed unconscious materials, shortcutting the years and prohibitive expense of psychoanalysis. In behavior change, they held the promise of reducing the recidivism of paroled prisoners. And in the area of my prime interest, they seemed to hold the promise of rolling back the materialistic worldview that imprisons us by showing people—causing them to see directly—that Nietzsche was wrong in announcing that God is dead.

RF: Was it apparent right from the start that these were religious sacraments when they arrived at Harvard in 1960?

HS: To me it was, though set and setting quickly entered the picture—“set” denoting the subject’s psychological makeup, and “setting” the circumstances in which the chemicals are ingested. This again makes me restive when you refer to them categorically as “religious sacraments,” for that seems to position them in a linear, one-to-one relationship with religion.

Others picked up on the resources of the drugs. Leary’s appointment was in the Center for Personality Research, and his chief interest was in the psychedelics’ potentials for behavior change, specifically changing asocial habits. One of the first experiments he designed involved his taking psilocybin with prisoners at the maximum security penitentiary in Concord and following up to see if it reduced their recidivism rate when they were paroled, which it seemed to do dramatically. (I have since learned that he may have fudged the data to make this point.) But for me, at the time, the important thing was the altered view of reality—what (in the title of one of his books) Carlos Castenanda called “A Separate Reality”—that the psychedelics repeatedly (though not invariably) brought to view. This was Aldous Huxley’s chief interest too. He arrived at M.I.T. for a semester as Distinguished Visiting Professor of Humanities in the same week that Tim took up his tenure at Harvard, and, having written The Doors of Perception, he was an important presence at the start of the Harvard experiment.

RF: Do you continue to feel that psychedelics are a way to see into a spiritual plane of reality?

HS: I do.

RF: Would perceiving that plane have social or political consequences?

HS: This a far-reaching and important question. It relates to the whole issue of whether metaphysical and religious outlooks—worldviews—affect history and shape it, or are simply head-trips that “bake no bread,” as the saying goes. Needless to say, I wouldn’t have gone into philosophy if I held the latter view. I’m with William James, who said that if a landlady were interviewing a prospective roomer she would do better to inquire into his philosophy than to ask about his bank account. Arnold Toynbee raised the stakes on James by asking who in the past have contributed the most to the present generation. His answer was Confucius and Lao-Tzu, the Buddha, the prophets of Israel and Judah, Jesus, Muhammad, and Socrates.

RF: Were you responsible for bringing Aldous Huxley to Cambridge that fall?

HS: Minimally. The Humanities Department at M.I.T. had a line item in its budget to bring a distinguished humanist to its campus each fall, and its chairman asked me what I thought of inviting Huxley. Needless to say, I was enthusiastic. When he accepted, I immediately volunteered to be his social secretary, managing his schedule, shepherding him to his appointments, and generally spending as much time with him as I could.

RF: Was your enthusiasm for Huxley related to his book, The Doors of Perception, that he published in 1953? Were you already curious about sacred drugs?

HS: Far more than curious; I found his book riveting. This needs a bit of explaining.

As you know but your readers may not, I was born of missionary parents in China and lived there until I came to the States for college. China was like the boondocks then, and I spent my college and graduate school years scrambling to catch up with the West and trying to become a full-blooded American. It seemed obvious that science and technology were what made the West dynamic and traditional societies stagnant, so I was an easy convert to the scientific worldview which I now see as scientistic rather than scientific.

RF: Some readers may not be clear as to the difference between science and scientism.

HS: Science consists of the actual discoveries of science and the method—the scientific method—which produces those discoveries. Scientism adds to those, first, the belief that the scientific method is, if not the only reliable way of getting at truth, then at least the most reliable method; and second, the belief that the things that science can get its hands on—physical, material, measurable things—are the most important things, the foundational, generating things from which all else derives. Nothing that science has discovered supports, much less proves, that those tacked-on points are true. They are no more than opinions, which my teachers led me to assume are true—there is truth in A. K. Coomaraswamy’s quip that it takes four years to get a college education and forty to get over it. I’m fortunate that it didn’t take me that long.

RF: What did the trick? What enabled you to see through scientism?

HS: That brings me back to Aldous Huxley. He had a sidekick, another Englishman named Gerald Heard. His name hasn’t lasted, but he was brilliant—H. G. Wells said that he was the only radio commentator (his beat was science) that he ever bothered to listen to. Heard is credited with having moved Huxley from his early Brave New World cynicism to the mysticism of The Perennial Philosophy. Have you heard of him?

RF: Sure. I have some letters here from Gerald Heard to Tim.

HS: Well I hadn’t, but I chanced—chance? Is there such a thing?—upon one of his books, Pain, Sex, and Time, and it proved to be the most important reading experience of my life. Let me warn those who might take that as a come-on for the book that it is unlikely that it would have the same impact on them. A book’s impact depends almost entirely on who the reader is and where he is on his life’s journey. I have never gone back to that book because I know I would find it disappointing now, for I am in a different place, but it spoke powerful to where I was then for being the first mystical book—book written from the mystic’s perspective—that I had ever read. It is the only time in my life that I read all night, and when dawn was breaking and I closed the book I closed out my naturalistic philosophy with it. The mystics’ worldview struck me as the truer of the two and I have never changed my opinion about that.

After that first book I went on to the others that Heard had written, and when I had read them all—quite a few—I decided that I wanted to meet the man, so I wrote him in care of his publisher. He replied, saying that he would be glad to see me but that it might be tricky to get to him, for he was in retreat, meditating as it turned out, in Trabucco Canyon about thirty-five miles from Los Angeles. I was about to move from the University of Denver to Washington University, and as St. Louis is farther from Los Angeles than Denver is, I hitchhiked from Denver to Trabucco Canyon. I had no car and was in debt from graduate school; it was easier to hitchhike then than it is now. As I was saying good-bye to Heard he asked if I would like to meet Aldous Huxley. “He’s interested in our kinds of things,” he said, and he gave me Huxley’s address in L.A. Huxley and his first wife Maria were at their cabin hideaway in the Mojave desert but their maid put me on the phone to them and they told me how to find their place by bus for what turned out to be a glorious afternoon. For the next fifteen years those two men were virtually my gurus, and Huxley’s anthology of mystical texts, The Perennial Philosophy, virtually my bible. I brought Huxley to lecture at Washington University and Heard to teach for a semester there.

That in itself was enough to excite me when The Doors of Perception appeared, but there was more. Mystical texts had convinced me that there is a separate reality but I wanted to experience it so I became a serious meditator in the hope of doing so. Unfortunately I turned out not to be good at that art—in Indian parlance, I’m a jnana rather than a raja yogi. I don’t regret the twelve or so years during which meditation was my spiritual path, and I have not given up meditating some each day. I find it useful for the focus it gives my life and for the way it helps me direct my attention, but I can’t alter the focal length of my consciousness by meditating. Even in the instance when I came closest to that goal, during my koan training in Japan, what happened was a radical reshuffling of components of this-worldly experience, not a visionary experience. I needed help to experience what the mystics experience, and Huxley’s mescalin held the possibility of providing it. So when he came to M.I.T. in 1960 I naturally raised the issue and he referred me to Leary who had enlisted him as a consultant for his project.

That’s a long answer to what sprung me from my naturalistic worldview.

RF: And it leads you to Tim. Do you recall your first meeting him?

HS: It was a luncheon date at the Harvard faculty club and I found him charismatic. His reputation for being brilliant had landed him a dream contract—full-time research on anything relating to personality theory he wanted to investigate. He was urbane, witty, and a great raconteur. On top of which he had style. The tailor in Harvard Square who specialized in outfitting Harvard professors had replaced his California casual wardrobe with natty, expensive English tweeds, replete with stylish leather elbow patches, but it was typical of Tim that he added a distinctive touch to his designer academic fashion by rounding it off with spanking white sneakers that gleaned as if they had been bought that morning. He was a marvelous performer and (I was to learn later) could read Finnegan’s Wake with such a flawless Irish brogue that he could have gone on stage.

The point of our meeting was to sign me up as a subject in his psychedelic project, which at that exploratory stage involved collecting firsthand reports of what subjects experienced when they took mescalin, or psilocybin, so as our lunch drew to its close, we pulled out our academic datebooks to schedule my first ingestion. The first several dates we tried wouldn’t work for one or the other of us, and finally Tim flipped past Christmas, eyed me with a mischievous grin, and said, “What about New Year’s Day?” I accepted and it turned out to be a prophetic way to enter the sixties.

RF: Did Tim come across as a spiritual person, or a brilliant intellectual—not that they are necessarily in conflict.

HS: Add his charm and I would say the latter. Also he had enormous self-confidence, which made him his own man. When he considered something to be important he went after it, regardless of what others thought. But I don’t recall ever having looked to him as a spiritual model, and I don’t think he saw himself in that role.

What I can say is that for the first three years of the Harvard project, my involvement in it was the most exciting thing in my life. Tim may have had other satellites in his orbit—he probably did, for his energy and exuberance were uncontainable—but the twenty or so people I was involved with constituted for those years my most important community. The important kind of experience that we shared, and others were ignorant of, bonded us far more solidly than I was bonded to my academic colleagues or members of my church. Some of the names of those in my group are still remembered in psychedelic circles: Dick Alpert who became Ram Dass; Walter Pahnke, an M.D. who mounted the Good Friday Experiment to earn a second doctorate in the psychology of religion; Walter Houston Clark, Professor of Psychology of Religion at Andover-Newton Theological Seminary; Ralph Metzner, who was to become Dean of the California Institute of Integral Studies; Paul Tillich’s teaching assistant Paul Lee, who I hired to teach at M.I.T. and who went on to teach at the University of California, Santa Cruz; Rolf von Eckartsberg, who became Professor of Psychology at Duquesne University; and Lisa Bieberman, who managed a journal that sprang up, The Psychedelic Review. Those are the ones I remember best. We would meet about every other week, sometimes for an all-night session with one of the substances, sometimes simply to discuss the religious implications of the psychedelics. During one of the all-night vigils a burning candle overturned and set fire to a lace window curtain. Soon thereafter (it was around 2:00 A.M.) Eleanor, my wife [she later answered to the name Kendra], who was not with us that evening, phoned to ask if everything was all right. She had been awakened by a vivid dream that Tim’s house (where we were meeting) was on fire.

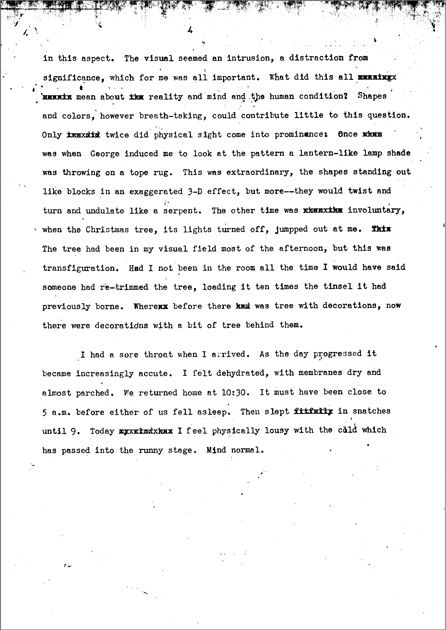

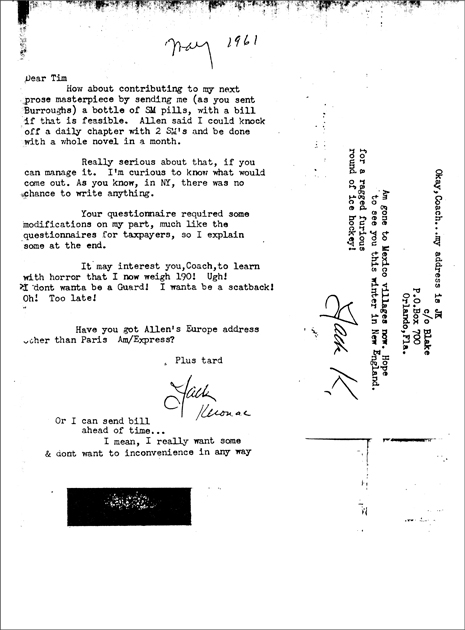

There was glamour in the mix, too. Tim’s project had become news, and it attracted the rich and the famous along with other curiosity seekers and would-be guinea pigs. More weekends than not Tim would spend in New York and return with gripping accounts of sessions with people we knew only by name. One that comes to mind is Jack Kerouac. He was known for picking fights when he was drunk, but he was mellow under LSD. Tim’s parting words to him were, “We had a good time and you didn’t throw a bean ball the entire weekend.”

There was a lot of humor in the picture. Michael Hollingshead arrived from England via John Beresford’s LSD project in New York City with a whole mayonnaise jar, large size, filled with LSD—as you know, I’m talking about a substance so potent that simply licking a postage stamp with a speck of LSD on it will put you into orbit. Basically he was a con man, but he had great plans to strike it rich in America by selling Hollywood this idea he had for a movie. The story line was about a man who wanted to seduce a young woman who had no use for him. He was determined, though, and resourceful, so he figured that if he could learn to levitate, that would get her attention. Transcendental Meditation claimed that it could cultivate that talent, so he signs on with them and practices diligently. Sure enough, there comes an evening when he realizes that his body is beginning to feel strangely light, and half an hour later it begins rising from his meditation pad. Excited, he phones his would-be lover and heads for her apartment. It isn’t easy going for his feet have difficulty maintaining traction with the sidewalk, but he gets there and she is indeed impressed—to the point that she agrees to return to his room with him. Taking her arm to keep himself grounded, they make it and by this time she is impressed enough to agree to acquiesce to his overtures. She goes into the bathroom to prepare herself, but when she emerges his levitating prowess has peaked and she finds him plastered to the ceiling, powerless to disengage himself. The closing scene of the movie was to have her stretched languidly on the bed beneath him, saying sweetly, “Anytime you’re ready baby, anytime you’re ready.” The movie never materialized.

The humor carried right through to the end of Tim and Dick Alpert’s Harvard odyssey. On the twentieth anniversary of their firings Tim and Ram Dass continued their flamboyant style by appearing at Harvard University to celebrate the occasion. The hall was jammed, and of course jazzed—and the ambiance resembled nothing so much as a concert by the Grateful Dead. The two principles were introduced by David McClelland, Chairman of the Department of Social Relations, who had fired them twenty years before. Wreathed in smiles, he was overflowing with warmth and goodwill, which made the contrast between the occasions captivating. But the contrast between firings and celebration was no greater than the contrast between the routes Tim and Ram Dass had traveled in the two decades. Ram Dass had found his guru in India while Tim had moved into high tech cyberspace. The finalist films for the Academy Awards that year were E.T. and Gandhi, and Tim, with his characteristic wit, pointed out that the contest was being enacted before the audience’s very eyes. He, into cyberspace, was obviously a stand-in for E.T., “while in that corner” he said, gesturing to Ram Dass, with his bald head, mustache, legs folded beneath him, and his eyes closed in meditation, “we have Gandhi.”

Underlying all these highjinks, what held us together was our feeling that we were on the cutting edge of knowledge. We were spearheading the acquisition of new and important truths and their potentials. We likened ourselves to explorers in Africa when that continent was still unknown to the Europeans. But given my temperament and my interests, it was always the spiritual value of the psychedelics that were the most important. They didn’t change my worldview, which had already become that of the mystics. What they did was enable me to experience their world—experience it as more solid and real than our everyday world, which it demoted to the shadows on Plato’s cave. And they taught me, again experientially, what awe is. For more than a decade I had been teaching my students that awe is the distinctive religious emotion combining two emotions, fear and fascination, which (apart from their religious joining) are in tension with each other. Fascination draws us toward the object in question while fear holds us back.

RF: In Flashbacks, Tim tells of a meeting with Lama Govinda, the great Buddhist sage and scholar, who reportedly said to Tim, “You are the predictable result of a strategy that has been unfolding for over fifty years. You have done exactly what the philosophers have wanted done. You were prepared discreetly by several Englishmen who were themselves agents of this process. You have been an unwitting tool of the great transformation of our age.” Thirty-five years after Lama Govinda reportedly made that statement, how does it sound to you, Huston?

HS: Lama Govinda’s Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism was so foundational in my understanding of that tradition that it took me to Almora, India, in the early 1960s for two weeks of unforgettable tutorials with him that lasted in the glorious setting of his hermitage until the sun set behind the Himalayas. But when I try to understand what he was getting at in that statement, I find myself unsure. What strategy was he thinking of, and what was it that he thought the philosophers wanted done? More than half my career has been in philosophy departments, and I haven’t noticed my colleagues being at all keen about what Tim was up to. Most important, what great transformation of our age was he thinking of? My guess is he was thinking of exceptional states of mind, and regions of reality that psychedelics can now make available to the public—people who can’t devote their lives (as Govinda did) to accessing them through meditation. I can see that as a great incursion in modernity, but has it transformed history? That’s difficult to answer.

Nena and Lama Govinda

RF: There came a time when you parted from Tim and Alpert. Was it an amicable parting?

HS: Very, as their parting with McClelland, their department chairman, had been. The organization that emerged from Tim’s experimental program called itself the International Federation for Internal Freedom—its abbreviation was poetic, for, freighted with ambiguities from the start, IFIF was the iffiest organization Cambridge had ever seen—and I was a founding member of it. But as the three years unfolded, differences began to appear with Tim and Dick on one side and Walter Houston Clark and I on the other. They were antiestablishment rebels, whereas Walter and I thought of ourselves as reformers. They were giving up on the university, where we were sticking with it. And—perhaps most importantly, for their was a lot of sex on their side—they were bachelors and we were married. So one night a formal parting of the ways took place. It occurred during a Thanksgiving overnight gathering of the clan at Millbrook, Peggy Hitchcock’s estate. Dinner was preceded by the traditional Thanksgiving touch football game, which Kendra remembers with delight because she was regularly assigned to block opponents and (as she put it) getting in people’s way was something she was good at. Her moment of glory was when she was assigned to block Maynard Ferguson.

Not surprisingly, the brownies were spiked with grass; but the pertinent part of my report came around midnight when Tim, Dick, Walter Clark, and I decided, with our friendship at full tilt, to face up to our differences, and Walter and I officially withdrew from IFIF and the direction it was headed. As we were the “squares” in the organization, I suggested that we might organize ourselves into IFIF squared with the logo IFIF2, though we did not in fact institute a parallel organization.

I remember one more moment that night which relates to Dick Alpert. As an assistant professor who was just beginning his career, he was so overshadowed by Tim’s glamour and status during those Harvard years that I confess I hadn’t paid much attention to him. But after our “parting-of-the-ways” discussion was over and I was heading upstairs to join Kendra for the night, he sought me out for the first one-on-one conversation we had ever had, as I recall. “I am sure that we will remain friends and continue to see each other,” he said, “but before we formally go our separate ways, I want to tell you that I have been impressed with the steadiness with which you have maneuvered these turbulent years.” It is self-serving for me to report that, but I do so because it was my first glimpse of the generosity of the man who was to become Ram Dass. Also, in a way that brief exchange was to prove prophetic, for in the years that followed I grew closer to Ram Dass than to Tim. Proximity has played a part in that—for the last fifteen years we have been neighbors on opposite sides of San Francisco Bay—but we also think more alike.

RF: I’m noticing now, Huston, as I’m watching your face when you talk about the football game at Millbrook and your other memories of Tim, that you seem to have a lot of affectionate and loving memories of Tim and those times. When I first asked you about contributing to this volume a couple of years ago, you declined. You said you didn’t want to be seen as endorsing Tim’s behavior, so you felt you couldn’t speak about it.

HS: That’s true.

RF: In 1961 he spoke at a conference with Huxley on “How to Change Behavior.” Already he was seeming very radical as he anticipated his critics:

Those of us who talk and write about the games of life are invariably misunderstood. We are seen as frivolous or cynical anarchists tearing down the social structure. This is an unfortunate misapprehension. Actually, only those who see culture as a game, only those who take this evolutionary point of view, can appreciate and treasure the exquisitely complex magnificence of what human beings do and have done. To see it all as “serious, taken-for-granted reality” is to miss the point; is to derogate with bland passivity the greatness of the games we learn.

What do you think of that statement?

HS: I think it polarizes, pitting them against us. Whatever Tim’s intentions were, what comes through is: you see us as a threat, whereas it’s only we who see life’s magnificence. His statement is unnuanced. And it is disingenuous, for in other situations he did talk about tearing down the social structure and—in jest but only half so—spiking the public water supply. And though it would be unfair to charge him with cynicism, he could be frivolous in the sense of being reckless and not as responsible as he should have been.

RF: He had a thoughtful rationalization for his attempted “juvenilization” of society. He cites Arthur Koestler:

Biological evolution is to a large extent a history of escapes from the blind alleys of overspecialization, the evolution of ideas a series of escapes from the tyranny of mental habits and stagnant routines. In biological evolution the escape is brought about by a retreat from the adult to the juvenile stage as the starting point for the new line; in mental evolution by a temporary regression to more primitive and uninhibited modes of ideation, followed by the creative leap.

And in his own words he writes:

The emergence of Hedonic Psychology in the 1960s was greeted with official scorn and persecution. Larval politicians correctly saw the cultural perils of hedonism. The neurosomatic perspective frees the human from addiction to hive rewards (which are now seen as robot) and opens up vistas of natural satisfaction and meta-social aesthetic revelation. The revelation is this: “I can learn to control internal, somatic function, to select, dial, tune incoming stimuli, not on the basis of security, power, success, or social responsibility, but in terms of aesthetics and psychosomatic wisdom. To feel good. To escape from terrestrial pulls.” (Info-Psychology, p. 29–30)

HS: There is some truth in all that, but again the polarization and absence of the qualifications and specifics. Suppose we accept Koestler’s statement. How, precisely, would/should we act and organize society if we were to “retreat from the adult to the juvenile stage as the starting point of the new line”? Throw tantrums? Play with matches? Expect others to feed us and clean up after us?

RF: I thought I noticed compatible notions in your writings that critique the modern world mindset. Particularly in the essays assembled into your book Beyond the Post-Modern Mind, wherein you describe the modern world mindset as an overly scientific, authoritarian, outer-directed, controlled, measured, “disqualified,” worldview that is giving way, thank goodness, to a perspective that values more the individual’s inner resources. “The supreme human opportunity is to strike deeper still and become aware of the ‘sacred unconscious’ that forms the bottom line of our selfhood” (p. 178).

You write:

Our final adversary is the notion of a lifeless universe as the context in which life and thought are set, one which without our presence in it would have been judged inferior to ourselves. Could we but shake off our anodynes for a moment we would see that nothing could be more terrible than the condition of spirits in a supposedly lifeless and indifferent universe—Newton’s great mechanism of time, space, and inanimate forces operating automatically or by chance. Spirits in such a context are like saplings without water; their organs shrivel. . . . So we must pick up anew Blake’s Bow of Burning Gold to support “the rise of the soul against the intellect” (Yeats) as intellect has come to be narrowly perceived. (p. 102)

HS: Tim was right in calling for that rise. Looking back, I think I agree with him in most of the things he was against. Reformers, as Walter Houston Clark and I regarded ourselves, are no more in love with the status quo than rebels are. The difference lies in how to change it. My concern is basically philosophical—to show that the diminished worldview that modernity’s misreading of modern science has caged us in is inaccurate. It was (and is) the promise psychedelics hold for helping to spring us from that cage that drew me to Tim and his Harvard experiment. I’m worried about social problems, too—overpopulation, environmental pollution, the growing gap between the rich and the poor—but I don’t have concrete solutions for them. I am not really a social philosopher.

RF: While Tim has become most visible for a kind of trivial psychedelic Pied Piperdom, there may have been some more historical, philosophical substance to his endeavors. Do you agree?

HS: Yes. But again, what were his specifics?

RF: Some folks hold him accountable for derailing the psychedelic movement by alienating it from mainstream society.

HS: Accountable is too strong. He probably contributed to it. There was a rebel streak in him that almost forced those in authority to react—every action elicits an equal and opposite reaction, as the saying goes. But questions of degree are difficult to answer—was Caesar a great man or a very great man? Tim appealed to the rebellious elements in the Western youths, and that’s not all bad. I admire Noam Chomsky greatly and he is very outspoken. But he stayed with the university and hasn’t lost his reputation. So the line between rebel and reformer is not a clear one.

RF: Letters such as the following from Gerald Heard seemed to provoke him to a revolutionary stance.

As you say the trinity of the 3 Ps Police, Priest, Paymaster (banker) is always against the journey of the soul but the current of consciousness is against the 3. For better or worse—better if you and the con[sciousness] chang[ing] druggist do it—worse if the politician is bright enough [in] his dark way to get in on the act. In either case, police, priest, and paymaster have had their day. Did you see that Glen Seaborg head of the A.E.C. asked what would be the big breakthrough in the next thirty years said in the consciousness changing drugs.

How did your group hope to infuse the virtues of the psychedelics into society?

HS: As I mentioned earlier, there never was an IFIF2, so it’s inaccurate to speak of my group. After the original IFIF it was for me a matter of cautious networking and writing as I struggled in the trail of William James, Aldous Huxley, and Gordon Wasson—and later, Albert Hofmann and Reuben Snake—to understand the workings of these substances and their import for religious living.

RF: I’ve been trying in the last several questions to get you to be critical, but you have been pretty muted. What was Tim’s shadow side?

HS: Judge not that ye be not judged: he did what he had to do. But his heritage is a mixed bag. He thrived on followers, and as the decades advanced he went to greater and greater lengths to get them—preparing groups to colonize outer space, touring the circuit as a stand-up comic with Gordon Liddy—until in the end it was hard to know what he stood for other than getting attention. And magical thinking seemed to enter the mix, as in his failure to check for the prostate cancer that killed him. He was not given to long-term commitments and the responsibilities that come with them—how many times was he married? His own family did not turn out well. When I asked him about getting addicted to the hard drugs he got into, he said, “You get addicted then you cure yourself.” That’s a recklessness answer. He never broke himself of the tobacco habit. When I introduced him for his final book reading at Cody’s Books in Berkeley—his early books were riveting, but that last one was a paste-up hodge-podge—he had to take a break at midpoint to go out on the deck for a cigarette. I am left looking back on his life with gratitude, and also with sadness. Gratitude not only for the doors to my psyche that he opened but also for the friendship, fun, and excitement he provided during those Harvard years. Sadness for the way his life went downhill. So much talent but a sad conclusion. His spirit remained unbroken, however.

RF: Are you surprised at what a mess there is now? Did you ever imagine back in 1960 that these drugs would be as forbidden, as illegal, as they are today?

HS: Initially I was utopian like everybody else. Whether it could have been different, I have no idea. Oh, things might be better now in little ways. The hysteria regarding drugs might be somewhat less if Tim and Dick had curbed some of their more flamboyant antics. But it remains an open question for me as to whether these substances can be openly integrated into society. I have used the image—lifted from Gerald Heard—of a beach ball in a lake. A part of it is always underwater. Gerald thought it must always be that way with society. There will never be a society where everything is above board because people have different tolerance levels. In the Victorian age you couldn’t talk about sex but the state of your soul was fair game. Now those topics are reversed.

RF: But we’re talking more about the soul now. Religious questions such as the existence of angels, life after death, spiritual laws of success, are making the bestseller list.

HS: You are quite right. Recently things have changed again. So perhaps the soul is coming back. And Tim may have helped to bring it back.

RF: There is such fear and ignorance that surrounds the mystical properties of psychedelic drugs, in spite of this interest in religion. Do you think that will ever change?

HS: I don’t know, but I find something in me resisting saying that it will. One of the thunderclap realizations of my first experience was that (as I have reported) I had never known what awe was, and the way it fuses fear and fascination. I have to confess that for me fear is a part of the psychedelic experience. Every time I approach the prospect of losing control and being ejected from the driver’s seat, I find myself fearful. And if that is endemic to the experience, fear may prevent an open acceptance of the psychedelics. Even in societies that don’t have the FDA stalking. So I’m not sure that nonacceptance can be chalked up to the three Ps—paymaster and so on. It may reside in the nature of these substances.

RF: You once told me of coming across Tim in Switzerland in the ’70s. Something he said to you seems relevant here.

HS: I know what you are referring to, and yes, it is relevant. Kendra and I were involved in a three-week seminar on Jung and Kazantzakis in Switzerland and I got word somehow that Tim was in the country. The original IFIF network was still sufficiently in place for me to track him and we arranged to meet in the town near my seminar site. This was on the heels of his prison break and escape from the United States—as hair-raising a story as I’ve ever heard—and he was wearing the dark aura of a wanted man. He roared into town in characteristic style on the back seat of a Harley Davidson driven by a Swiss buddy of his. It was wonderful to see him again, out of prison and free, but what I remember best was his statement, early in our conversation, that you are asking me to repeat, which was, “Nobody ever changes, do they, Huston?” Like so many of Tim’s observations, it was deeply discerning. Here we were, in a foreign land, thousands of miles from Cambridge, so much had happened for both of us. But I was still on the spiritual journey that was my priority before I encountered Tim and the psychedelics. And he was still a fugitive from lawful society—kicked out of it as he had been kicked out of West Point, Harvard University, and Zihuatanejo.

RF: We still have this conflict between the materialist’s “scientific” worldview and that of the mystic. You can end it, in a way, with psychedelic drugs. You can see, in a scientific way, that is, a systematic way, that the numinous does exist, that there is a sacred, that God consciousness may be more fundamental than the materialist’s claim. You can prove the reality of the mystic’s experience.

HS: You can prove it to me, but then I didn’t need proof—I believed that the mystics were right before I encountered the psychedelics. And I’m afraid that the same holds for the disbelievers. Materialists have to agree that the psychedelic can generate mystical experiences, but there is nothing in those experiences that forces people to accept that they tell us what the world is like. Bertrand Russell is a case in point. Asked if he had ever had a mystical experience, he answered, “Many.” “What did you do with them?” “I dismissed them.”

RF: I’m trying to follow Huxley’s thought here. As he said in an early paper, “Visionary Experience,” given with Leary in 1961 in Copenhagen:

These biochemical methods are, I suppose, the most powerful and the most foolproof, so to say, of all the methods for transporting us to this other world that at present exist. I think, as Professor Leary will point out tonight, that there is a very large field for systematic experimentation by psychologists, because it is now possible to explore areas of the mind at a minimum expense to the body, areas which were almost impossible to get at before, except either by the use of extremely dangerous drugs or else by looking around for the rather rare people who spontaneously can go into this other world. (Of course it is very difficult for them to go in on demand, “the Spirit bloweth where it listeth,” we can never be sure that the people with the spontaneous gift of visionary experience will have it on demand.) With such drugs as psilocybin it is possible for the majority of people to go into this other world with very little trouble and with almost no harm done to themselves.

HS: That wise man; I don’t recall having read anything by Huxley that didn’t strike me as right on. But note the qualification in the passage you quoted. It says that psychedelics are “the most” foolproof, not that they are foolproof, which is what would be required to turn skeptics into mystics.

RF: I’ll concede that distinction but even so, doesn’t it seem strange to you that theological seminaries and monastaries ignore this “most powerful and most foolproof” way of accessing the divine? Religious training, or metaphysical inquiry, seems to provide the ideal context for these drugs.

HS: Here I’m completely with you. Of course, legal space would have to be carved out for this to happen, and even with that space they should be offered as an elective, so to speak, and not part of the required curriculum. For I don’t see that anything that has happened since the Wassons published their groundbreaking Russia, Mushrooms and History that counters the premise of that book, which is that “mushrooms” mean close to everything to half the world while the other half views them phobicly, as toadstools.

RF: In that same conference in Copenhagen Huxley raised the question: “Of course we come now to the philosophical problem: what is the metaphysical status of visions, what is the ontological status? . . . it is worth going into, and I hope someone will go into it sooner or later.” I wonder if we’ll ever get around to that in this culture?

HS: Huxley got around to it, and William James, Gordon Wasson, and Albert Hofmann all got around to it. You are getting around to it and I got around to it in the key essay I have written on the subject, “Do Drugs have Religious Import?” which has been anthologized more than twenty times, mostly in textbooks. So the thrust of your question is whether our society will get around to giving the question the attention it deserves.

Who knows? As Bob Dylan sang, “the answer is blowing in the wind.” I am not entirely discouraged, however. I never thought that I would live long enough to be invited to give a well-publicized lecture on psychedelics and religion at a major university. It was at Northern Illinois University, two years ago. It was as if I were back at Harvard when the topic was respectable. Still I don’t know where we’re headed. It’s like when Dizzy Gillespie was asked about the future of jazz. He said, “Man, if I knew where jazz is going, I’d be there already.”