Moron.

It has been my experience that most problems in life are caused by a lack of information. Many people just don’t know the things they need to know. Some ignore the truth; others never understand it.

When two friends get mad at each other, they usually do it because they lack information about each other’s feelings. Americans lack information about Librarian control of their government. The people who pass this book on the shelf and don’t buy it lack information about how wonderful, exciting, and useful it is.

Take, for instance, the word that started this chapter. You lacked information when you read it. You likely assumed that I was calling you an insulting name. You assumed wrong. Moron is actually a village in Switzerland located near the Jura mountain range. It’s a nice place to live if you hate Librarians, for there is a well-hidden underground rebellion there.

Information. Perhaps you Hushlanders have read about Bastille and the others referring to guns as “primitive,” and have been offended. Or perhaps you simply thought the text was being silly. In either case, maybe you should reevaluate.

The Free Kingdoms moved beyond the use of guns many centuries ago. The weapons became impractical for several reasons—some of which should be growing apparent from this narrative. Smedry Talents and Oculator abilities are not the only strange powers in the Free Kingdoms—and most of these abilities work better on items with large numbers of moving parts or breakable circuits. Using a gun against a Smedry, or one similarly talented, is usually a bad idea.

(This comes down to simple probability. The more that can go wrong with an item, the more that will. My computer—when I used to use one—was always about one click away from serious meltdown. My pencil, however, remains to this day remarkably virus-free.)

And so, many of the world’s soldiers and warriors have moved on from guns, instead choosing weapons and armor created from Oculatory sands or silimatic technology. They don’t often associate these items with their ancient counterparts—the people of the Free Kingdoms never got much beyond muskets before they moved on to using sand-based weapons—and so they think that guns are the primitive weapons. It makes sense, if you look at it from their perspective.

And anyone who’s not willing to do that … well, they might just be a moron. Whether or not they live there.

“Sing, put those primitive guns away!” Bastille snapped, stepping away from the hole in the floor. “Those shattering things are so loud that half the library must have heard your racket!”

“They’re effective though,” Sing said happily, changing the clips in a pair of his pistols. “They stopped that Alivened long enough for Alcatraz to take it down. I didn’t see your sword doing half as well.”

Bastille grumbled something, then paused, frowning. “Why is it so hot in here?”

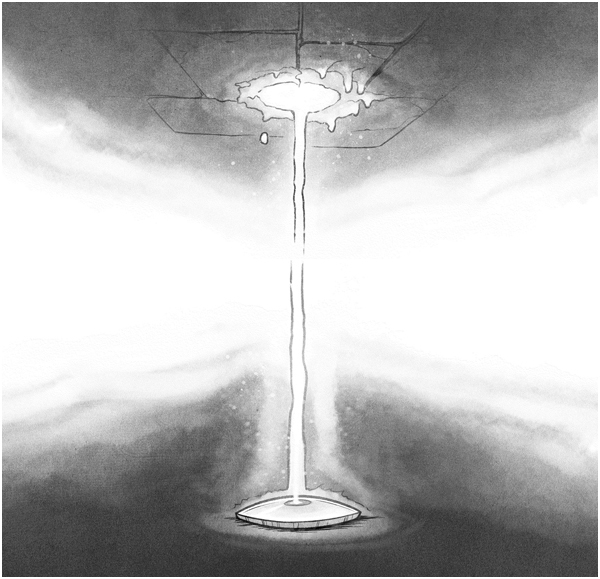

I cursed, turning toward the glowing, smoking stones around the Firebringer’s Lens. The floor looked dangerously close to becoming molten.

“I still can’t believe old Smedry gave you a Firebringer’s Lens,” Bastille said. “That’s like…”

“Giving a bazooka to a four-year-old?” I asked. I edged as close to the heated stones as I could stand. “That’s kind of what I feel like when I pick the thing up.”

“Well, turn it off!” Bastille said. “Quickly! You think Sing’s guns were loud—using an Oculatory Lens that powerful will draw Blackburn’s attention for certain. The longer you leave it on, the more loud it will seem!”

The reference to loudness probably doesn’t make much sense to non-Oculators. After all, the Lens didn’t make any noise. However, as I tried to figure out a way to turn off the Firebringer’s Lens, I realized that I could feel it. Even though I’d only been aware of my Oculatory abilities for a short time, I was already getting in synch with them enough to sense when a powerful Lens was being used nearby.

The point is, I knew Bastille was right. I needed to turn that Lens off quickly. If Blackburn hadn’t heard the gunfire, then he’d certainly notice the Lens “noise.”

“Sing, loan me that shotgun,” I said urgently, waving with my hand.

Sing reluctantly relinquished the weapon. As soon as I touched it, the barrel fell off—but I was ready for that. I grabbed the tube of steel and used it to flip the Firebringer’s Lens over. The Lens was convex, meaning it bulged out on one side, and now that it was flipped over it looked like a translucent eyeball staring up out of the ground. It continued to fire its superhot ray of light, which was now directed at the ceiling.

I used the barrel of the gun to scoot the Lens away from the heated section of the floor, then carefully reached out. I gritted my teeth—expecting to get burned—and touched the side of the Lens.

Remarkably (as I’ve mentioned before) the glass wasn’t even hot. As soon as I touched it, the Lens shut off, the ray of light dwindling. I stepped back, surprised at how cold and dark the corridor now seemed by comparison.

“My shotgun,” Sing said despondently as I handed back the barrel. “This was an antique!”

That’s what happens when you stay around me, Sing, I thought with a sigh. Things that you love get broken. Even when I don’t do it on purpose.

“Oh, get off it, Sing,” Bastille said. “I lost my sword—you can’t even understand how much trouble I’ll be in for that. I was already bonded to the shattered thing; now I’ll have to start the process all over, if they even let me. Next to that, your gun is nothing.”

Sing sighed but nodded as Bastille reached into her handbag and pulled out a large crystalline knife. You may, by the way, have noticed the connection between the word Crystin and the weapons made of crystal that Bastille uses. This is actually a coincidence. Crystin is the Vendardi word for “grumpy,” which all Crystins tend to be. And I think …

Nah, I’m just kidding. They got the name because they use crystal swords. Plus, they live in a big castle (dubbed Crystallia) made of—you guessed it—crystals. That clear enough? Crystal clear?

Ahem.

“I’m out of bullets for the Uzis too,” Sing said, looking in his bag. “Small weapons for us both, I guess.”

I knelt down and tentatively poked the Firebringer’s Lens, still trying to pick it up off the floor. It began to glow. Blast! I thought and touched it again. The glow dissipated.

“Try being dumb,” Bastille suggested.

“Excuse me?” I asked, frowning.

“Think dumb thoughts,” Bastille said. “Or try not to think very much at all. The Lenses react to information and intelligence. So, it’s easiest to handle them when there isn’t much of either one around.”

I paused. Then I frowned and looked at the Lens, trying my best to be … well, stupid. I would like to note that this is quite a bit more difficult than it might sound. Particularly for a person like me, who can be (has this been mentioned?) rather clever.

Not only is it against a rashional purson’s nature to try and convince himself that he is more stoopid than he thinks he is, it is quite dificult to not think about anything when one has been told not to. Only the trooly most briliant of peeple can purrtend stoopidity so sucessfuly.

Butt eet kan bee dun.

I closed my eyes and tried to empty my mind. Then I reached for the Lens. It started to glow. I frowned, then tapped it before it could go off.

“Maybe we should simply leave it,” Sing said nervously. “Before someone sees us.”

“Too late,” Bastille said, nodding down the hallway, to where a group of robed Librarians had just appeared around a corner. They looked quite anxious, and I suspected that Bastille had been right in her earlier comment. The gunfire had been heard.

Bastille glanced at them through her sunglasses, then flipped her knife in her hand, raising it to throw.

“No!” I said. “Wait!”

Dutifully, she paused. The Librarians scattered, several racing back the way they had come.

“Why did you stop me?” Bastille asked testily.

“Those aren’t paper monsters, Bastille,” I said. “Those are unarmed people. We can’t kill them.”

“We’re at war, Alcatraz. Those people are the enemy. Plus, they’re going to alert Blackburn!”

I shrugged. “It just didn’t feel right. Besides, there were too many for you to kill them all. We can’t keep our escape secret any longer.”

Bastille snorted but otherwise fell silent. Either way, I didn’t have any more time for acting stupid. I grabbed the Lens—it began to glow—and quickly shoved it back inside its velvet pouch. Then I reached in and tapped it off with a finger. I pulled the bag shut, then stuffed it in my pocket.

“Let’s go then,” I said.

Bastille nodded. Sing, however, had moved over to the pile of ripped, shredded papers that were the remnants of the Alivened. “Alcatraz,” he said. “There’s something here you should see.”

“What?” I asked, hurrying over. As I approached, I could see that in the center of the pile, Sing had found what appeared to be a portion of the Alivened that was still … well, alivened.

It sat up as I arrived, prompting Sing to point a pistol at it. The creature was smaller now, and it was much more human-shaped. However, it was still made of crumpled-up paper, and now that I was close, I could see that it had two beady, glassy eyes.

I frowned, looking at Sing. “What’s going on?”

“I don’t know,” Sing said. “Of course, I don’t know a lot about Alivening. It’s Dark Oculary.”

“Why?” I asked, watching the three-foot-tall paper man with suspicious eyes.

“Bringing an inanimate thing to life this way is evil,” Bastille said. “To do it, the Oculator has to give up a bit of his own humanity and store it in Glass of Alivening. That’s what those eyes are made of. Shoot it, Sing. If you hit it in the eye, you might be able to kill it.”

The little paper creature cocked its head, quizzically staring down the barrel of the gun.

I looked back at Bastille. “They give up a bit of their own humanity? What does that mean?”

“They let the glass drain them of things,” Bastille explained.

“Things? That’s specific.”

From the side, I could see Bastille narrow her eyes behind her sunglasses, staring at the little creature with suspicion. “Human things, Alcatraz. Things like the capacity to love, protect others, and have mercy. Each time an Oculator creates an Alivened, he makes himself a little less human. Or at least he makes himself a little less like the kind of human the rest of us would want to associate with.”

Sing nodded. “Most Dark Oculators think the transformation is an advantage.” He reached down with his free hand, still keeping his gun leveled at the small Alivened. He held up a ripped bit of paper.

“You’d think that by giving up part of his humanity,” the anthropologist said, “the Dark Oculator would create a creature that possessed good emotions. But that’s not the way it works. The process twists the emotions, creating a creature that has just enough humanity to live, but not enough of it to really function.”

I accepted the scrap of paper. I could read the text—it appeared to be prose. The title line at the top right corner read The Passionate Fire of Fiery Passion.

“You can make an Alivened out of virtually anything,” Sing said. “But substances that soak up emotion tend to work the best. That’s why a lot of Dark Oculators prefer bad romance novels, since the object used determines the Alivened’s temperament.”

“Romance novels make an Alivened very violent,” Bastille said. “But rather dense in the intelligence department.”

“Go figure,” I said, dropping the scrap of paper. They give up their own humanity.… And this was the monster that was holding my grandfather captive. “Come on,” I said, standing. “We’ve wasted too much time already.”

“And this thing?” Sing asked.

I paused. The Alivened gazed up at me, its paper face somehow managing to convey a look of confusion.

I … broke it somehow, I thought. I thought I’d killed it—but that’s not the way my Talent works. I don’t destroy, not when the Talent is in full form. I just break and transform. “Leave it,” I said.

Sing looked up in surprise.

“We don’t want any more gunshots,” I said. “Come on.”

Sing shrugged, rising. Bastille moved down the hallway, checking the intersection. I quickly swapped my Oculator’s Lenses for my Tracker’s Lenses—fortunately, my grandfather’s footprints were still glowing.

I didn’t think I knew him that well, I thought.

I met Bastille at the intersection, pointing to the right branch. “Grandpa Smedry went that way.”

“The same way the Librarians went,” she said. “After they discovered us.”

I nodded, glancing in the other direction. I pointed. “I see Ms. Fletcher’s footprints that way.”

“She turned away from the others?”

“No,” I said. “She didn’t go with Grandpa Smedry from the dungeons. Those footprints I can see now are the original ones we followed—the ones that led us to the place we got captured. I told you we were close to where we started.”

Bastille frowned. “How well do you know this Ms. Fletcher?”

I shrugged.

“It’s been hours,” Bastille said. “I’m surprised her footprints are still glowing.”

I nodded. As I did, I noticed something else odd.

(If you haven’t noticed, this is the chapter for noticing weird things. As opposed to the other chapters, in which only normal things were ever noticed. There is a story I could tell you about that, but as it involves eggbeaters, it is not appropriate for young people.)

The normalcy-challenged thing that I had noticed was was really not very odd, all things considered. It was a lantern holder—the ornate bracket that I’d ripped free when I’d thrown the lantern at the Alivened.

There was nothing all that unusual about this lantern bracket, except for the already-noted fact that it was shaped like a cantaloupe. For all I knew, cantaloupe-shaped library lanterns were quite normal. Yet the sight of this one sparked a memory in my head. Cantaloupe, fluttering paper makes a duck.

I glanced back at the hallway behind me, with its broken wall, more broken floor, and piles of paper that shuffled in the draft.

It’s probably nothing, I thought.

You, of course, know better than that.