I seem to recall that last year a Free Kingdoms biographer wrote an article claiming I had spent my childhood performing a “deep infiltration” of Librarian lands. I guess in his mind, spending my life eating Twinkies and playing video games counted as a “deep infiltration.”

I hope you Free Kingdomers aren’t too put out to discover that dragons didn’t come and bow to me at my birth. I wasn’t tutored by the spirits of my dead Smedry ancestors, nor did I kill my first Librarian by slitting his throat with his own library card.

This is the real me, the troubled boy who grew into an even more troubled young man. Now, I’m not a terrible person. I’m just not a particularly nice one either. If you’d been tied to altars, nearly eaten by walking romance novels, and thrown off a glass pillar taller than Mt. Everest, you might have turned out a little like me yourself.

Sing tripped.

Now, I’ve seen a lot of people trip in my lifetime. I’ve seen people stumble, tumble, and misstep. I once saw my foster brother fall down the stairs (not my fault) and I also saw a local bully belly flop when his diving board broke beneath him (I plead the Fifth on that one).

I have never, however, seen a trip quite so … well executed as the one Sing performed in the library lobby that day. The hefty Mokian quite convincingly stumbled on the welcome mat right inside the doors. He cried out, hopping on one foot—a teetering, lumbering mound with the kinetic energy of a collapsing building.

People scattered. Children cried, clutching picture books about aardvarks in their terrified fingers. A Librarian raised her hand in warning.

With a weird mixture of skillful grace and a mad lack of control, Sing fell over a comfortable reading chair and collided with a massive bookshelf. Those shelves are—you may know—usually bolted to the floor. That didn’t matter. When confronted with a three-hundred-and-fifty-pound Mokian missile, iron bends.

And the bookshelf fell.

Books flew in the air. Pages fluttered. Metal groaned.

“Now’s our chance,” Grandpa Smedry said. He dashed forward, just one more body in the flurry of lobby activity.

The rest of us followed, scooting past the horrified Librarians. Grandpa Smedry led us behind the children’s section, through the media section, and to a pair of shabby doors at the back marked EMPLOYEES ONLY.

“Put your Oculator’s Lenses back on, lad,” Grandpa Smedry said, sliding on his reddish pair.

I did so as well, and through those Lenses I could see a certain faint glow around the doors. Not a white or black glow like I’d seen before. But instead … a bluish one. The power was focused on a square in the wall. On closer inspection, I could see that that section of the wall was inset with a small square of glass.

“A Hushlander handprint scanner,” Grandpa Smedry said. “Kind of like Recognizer’s Glass. How quaint. All right, lad, it’s your turn.”

I gulped quietly, feeling nervous—both because of the Librarians so near and because everyone was counting on me. I reached out and pressed my hand against the door. There was a hum from the glass panel, but I ignored it. Instead I focused on myself.

I’d always known, instinctively, about my power. I’d always had it, but I’d rarely tried to control it specifically. Now I focused on it, and I felt a tingle—like the shock that comes from touching a battery to your tongue—pulse out of my chest and down my arm.

There was a crack from the door as the lock snapped. “Masterfully done, lad!” Grandpa Smedry said. “Masterfully done indeed.”

I shrugged, feeling proud. “Doors have always been my specialty.”

Quentin quickly pushed open the door and waved everyone through. Grandpa Smedry’s eyes twinkled as he passed me. “I’ve always wanted to do this,” he whispered.

I could hear Bastille grumbling something under her breath as she joined us in the hallway, Sing’s bag of guns slung over her shoulder. Quentin held the door open for a moment longer, and finally a puffing Sing rounded the bookshelves and joined us.

“Sorry,” he said. “One of the female patrons insisted on wrapping my ankle for me.” Indeed, his sandal-shod right foot now bore a support bandage.

Quentin closed the door, then checked the handle, twisting it a few times. “Coconuts, the pain don’t hurt,” he said, then paused. “Sorry,” he said, flushing. “Sometimes the gibberish comes out when I don’t want it to. Anyway, the lock is still broken—it will be suspicious next time someone comes through here.”

“Can’t be helped,” Grandpa Smedry said, pulling out what appeared to be two small hourglasses. He gave them each a tap, and the sand started flowing. He handed one to me. The sand continued to flow at the same rate no matter which way I turned the device. Nifty, I thought. I’d always wanted a magical hourglass.

Well, not really. But if I’d known that there were such things as magical hourglasses, I’d have wanted one. Who wouldn’t? I should note, however, that the Free Kingdomers would be offended by my calling the hourglass magical. They have very strange feelings on what counts as magical and what doesn’t. For instance, Oculatory powers and Smedry Talents are considered a form of magic to most Free Kingdomers, since they are things that can only be performed or used by a few select people. The hourglasses, like the silimatic cars, Sing’s glasses, or Bastille’s jacket, can be used by anyone. That makes those things “technology” in Free Kingdomer speak.

It’s confusing, I know. However, you’re probably smart enough to figure it out. And if you aren’t, then I shall likely call you an insulting name. (Wait for Chapter Fifteen.)

“We’ll meet here in one hour,” Grandpa Smedry said. “Any longer than that, and we’ll be getting close to closing time. When that happens, all those Librarians out on patrol will return to check in—and we’ll be in serious trouble. Quentin is with me—Sing and Bastille, go with Alcatraz.”

“But—” Bastille said.

“No,” Grandpa Smedry interrupted. “You’re going with him, Bastille. I order you to.”

“I’m your Crystin,” she objected.

“True,” Grandpa Smedry said. “But you’re sworn to protect all Smedrys, especially Oculators. The lad will need your help more than I will.”

Bastille huffed quietly but made no further objections. As for myself, I wasn’t really sure whether to be annoyed or glad.

“You three inspect this floor, then move up to the second one,” Grandpa Smedry said quietly. “Quentin and I will take the top floor.”

“But,” Bastille said, “that’s where the Dark Oculator is!”

“That’s where his lair is,” Grandpa Smedry corrected. “That aura glows so brightly because he spends so much time there. You might be able to notice the Dark Oculator’s own aura if he’s nearby, Alcatraz, but it won’t give you much advance warning. Stay quiet and unseen, all right?”

I nodded slowly.

Grandpa Smedry stepped a little closer, speaking quietly. “If you do run into him, lad, make certain you keep those Oculator’s Lenses on. They can protect you from an enemy’s Lenses, if you use them right.”

“How … how do I manage that?” I asked.

“It takes time to practice, lad,” Grandpa Smedry said. “Time we don’t have! But, well, it probably won’t come to that. Just … try to stay away from any rooms that shine black, okay?”

I nodded again.

“Well, then!” Grandpa Smedry said to the whole group. “The Librarians will have to spend ages cleaning up that mess in the lobby. Hopefully they won’t even notice the door until we’re gone. One hour! Quickly now. We’re late!”

With that, Grandpa Smedry spun to the left and began walking down the empty white hallway. Quentin waved good-bye. “Rutabaga, fire over the inheritance!” he said, then rushed after the elderly Oculator.

Sing and Bastille turned to me. It … looks like I’m in charge, I thought with surprise.

This was a strange realization. Yes, yes, I know—Grandpa Smedry had already said that I would have to lead my group. I shouldn’t have been surprised to find myself in this situation.

The truth is, however, that I was never the sort of person that people put in charge. Those kinds of duties generally go to the types of boys and girls who deliver apples, answer questions, and smile a lot. Leadership duties do not generally go to boys whose desks collapse, who are often accused of playing pranks by removing the doorknobs of school bathrooms, and who once unwittingly made a friend’s pants fall down while he was writing on the chalkboard.

I never did manage to get that stunt to work again.

“Um, I guess we go this way,” I said, pointing down the hallway.

“You think?” Bastille asked flatly, handing Sing his gym bag of guns. She pulled a pair of sunglasses—Warrior’s Lenses, as the others called them—out of her jacket pocket and slipped them on. Then she took off, walking down the hallway, handbag flipped around her shoulder.

If I ordered her to go back and follow Grandpa instead, I wonder if she’d go.… I decided that she probably wouldn’t.

“Say, Alcatraz,” Sing said as we followed Bastille. “What do you suppose this little wrap on my ankle means?”

I frowned, glancing down. “The bandage?”

“Oh,” Sing said. “Is that what it is? First aid, it is called, correct?”

“Yes,” I said. “Why else would someone wrap your ankle like that?”

Sing glanced down, obviously trying to inspect the ankle bandage while still walking. “Oh, I don’t know,” he said. “I thought maybe it was some preliminary courtship ritual.…” He trailed off, looking toward me hopefully.

“No,” I said. “Not a chance.”

“That’s sad,” Sing said. “She was pretty.”

“Is that the sort of thing you should be thinking about?” I asked. “I mean, you’re an anthropologist—you study cultures. Are you allowed to interfere with the ‘natives’ you meet?”

“What?” Sing said. “Of course we can! Why, we’re here to interfere! We’re trying to overthrow Librarian domination of the Hushlands, after all.”

“Why not just let people live their lives, and live yours?”

Sing looked taken aback. “Alcatraz, the Hushlanders are enslaved! They’re being kept in ignorance, living only with the most primitive technologies! Besides, we need to do something to fight. Back at the Council of Kings, some people are starting to talk about surrendering to the Librarians completely!” He shook his head. “I’m glad for people like your grandfather, people willing to take the fight into Librarian lands. It shows that we won’t simply sit back and slowly have our kingdoms taken from us.”

Up ahead, Bastille glared back at us. “Would you two like to chat a little more?” she snapped. “Perhaps sing a little tune? If there are any Librarians in front of us, we wouldn’t want them to miss out on hearing us coming.”

Sing looked at his feet sheepishly, and we fell silent—though a part of me wanted to yell something like, “What did you say, Bastille?” as loudly as I could. You see, that is the sad, sorry, terrible thing about sarcasm.

It’s really funny.

But I just walked quietly, thinking about what Sing had said—particularly the part about the Librarians only letting Hushlanders have the most “primitive” of technologies. It seemed ridiculous to me that the Free Kingdomers considered things like guns and automobiles to be “primitive.” They weren’t primitive, they were … well, they were what I knew. Growing up in America, I’d come to assume that everything I had—and did—was the newest, best, and most advanced in the world.

It was very unsettling to be confronted by people who weren’t impressed by how advanced my culture was. I wanted to huff and think that whatever they had must not be all that good either. Except the problem was that I’d seen that they had self-driving cars, glasses that could track a person’s footprints, and armored knights. All were, in one way or another, superior to what I’d known. (Admit it, knights are just cool.)

I was coming to realize something very difficult. I was slowly accepting that the way I did things—the way my people did things—might not actually be the best way.

In other words, I was feeling humility.

I sincerely hope that you never have to feel this emotion. Like asparagus and fish, it’s not really as good for you as everyone says it is. Selfishness, arrogance, and callousness got me much further than humility ever did.

Have I mentioned that I’m not really a very good person?

Our small group reached the end of the unmarked hallway, Bastille still in the lead. She paused, holding up a hand, peeking around the corner. Then she continued onward, her platform sandals making a slight noise as she stepped onto a carpeted floor. Sing and I followed. The room beyond was filled with books.

Really filled.

Perhaps you’ve never experienced the full, suffocating majesty of a true library. You Hushlanders have probably visited your local libraries—you’ve perused the parts that normal people are allowed to see. These places tend to have row upon row of neat bookshelves, arranged nicely. They are presented attractively for the same reason that kittens are cute—so that they can draw you in, then pounce on you for the kill.

Seriously. Stay away from kittens.

Public libraries exist to entice. The Librarians want everyone to read their books—whether those books are deep and poignant works about dead puppies or nonfiction books about made-up topics, like the Pilgrims, penicillin, and France. In fact, the only book they don’t want you to read is the one you’re holding right now.

Those aren’t real libraries, however. Real libraries take little concern for enticement. You who have visited the basement stacks of a university library’s philosophy section know what I’m talking about. In such places, the shelves get squeezed closer and closer together, and they reach higher and higher. Piles of books appear randomly at junctions and in corners waiting to be shelved, like the fourth-generation descendants of a copy of Summa Theologica and an edition of Little Women.

Dust settles on the books like a gray perversion of rain forest moss, giving the air a certain moldy, unwelcome scent faintly reminiscent of a baledragon’s lair. At each corner, you expect to turn and see the withered, skeletal remains of some poor researcher who got lost in the stacks and never found his way out.

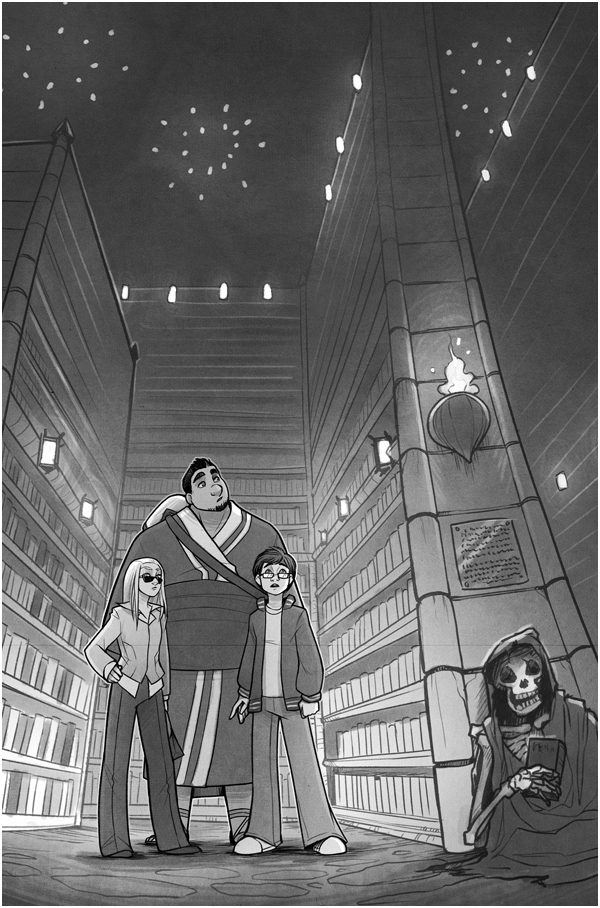

And even those kinds of libraries are but pale apprentices to the enormous cavern of books that I entered that day. We walked quietly, passing shelves packed so tightly together that only an anorexic racing jockey could have squeezed between them. The bookshelves were easily fifteen feet high, and enormous plaques on the ends proclaimed, in very small letters, the titles each one contained. Long wooden poles with pincerlike hooks leaned against some shelves, and I got the impression that they were used for reaching between the shelves to pull out books.

No, I thought, it would take a ridiculous amount of practice to learn to do something like that. I must be wrong.

You may have guessed that I wasn’t actually wrong. You see, Librarian apprentices have plenty of time to practice things that are ridiculous. They really only have three duties: First, to learn the incredibly and needlessly complicated filing system used to catalog books in the back library stacks. Second, to practice with the book-hooks. Third, to plot ways to torture an innocent populace.

That third one is the most fun. Kind of like gym class for the murderously insane.

Sing, Bastille, and I crept along the rows, careful to keep an eye out for Librarian apprentices. This was undoubtedly the most dangerous thing I’d ever done in my short life. Fortunately, we were able to get to the eastern edge of the room without incident.

“We should move along the wall,” Bastille said quietly, “so Alcatraz can look down each row of books. That way, he might see powerful Oculatory sources.”

Sing nodded. “But we should move quickly. We need to find the sands and get out fast, before the Librarians realize they’ve been infiltrated.”

They looked at me expectantly. “Uh, that sounds good,” I finally said.

“You’ve got this leadership thing down, Smedry,” Bastille said flatly. “Very inspiring. Come on, then. Let’s keep moving.”

Bastille and Sing began to walk along the wall. I, however, didn’t follow. I had just noticed something hanging on the wall above us: a very large painting that appeared to be an ornate, detailed map of the world.

And it looked nothing like the one I was used to.