![]()

![]()

THE first structures in New Hampshire were built by individual pioneers. In the southeastern part of the State these pioneers were fishermen and traders in furs with the Indians. On the Connecticut River they were traders and farmers who sought the rich alluvial lands along the river. In the second phase, colonies and settlements were organized in England, or sprang up as shoots from older colonies to secure rich land or to find freedom from particular religious practices.

In these developments, fortresses, blockhouses, or garrisons were the first buildings, followed by houses, churches, and gristmills. A few of the garrisons, fairly complete, are practically all that remains. The Dam House at Dover, built in 1675, is a good example of a one-story garrison house. These structures were generally of heavy squared logs, with dovetailed corners, small windows or portholes, and an overhang completely around the building. Doors were disproportionately thick and heavy, for defense against the Indians. Another existing example is the Gilman Garrison House (1658) at Exeter, which, however, preserves less of its original character. This was of the more common two-story type. In the Cobleigh Tavern at Lisbon, an original blockhouse dating from about 1750 was enclosed by a later building, and now is a part of the second story of the building.

Houses were framed after the English manner, and may be divided into periods. The first period is reminiscent of Tudor work in England; the second is inspired by the work of Wren and his contemporaries, which was the tradition here from about 1700 to 1790; the third, following 1790, is in the lighter and more graceful manner reminiscent of the Adam brothers in England, but humanized and adapted to the local setting by American builders.

The early houses on the seacoast and shores of Great Bay and its tributary waters were built in the manner of the first period. Of these, the Jackson House (1664) in Portsmouth is one of the few survivors, and a careful restoration has disclosed its full beauty. This frame house with its weathered clapboards, five leaded casements in the main façade, and an unornamented doorway has a sharply pitched roof brought in a slight curve to the ground level at the rear. On the right side a small ell continues the line of the roof, while on the left is a one-story lean-to. The Guppy House (1690) at Dover has the pitched roof sloping almost to the ground, but the leaded windows of the earlier house have here given way to the small-paned sash. Representing a later development of this period is the Old Parsonage at Newington (1697), with the long rear roof ending at the windows of the first story, and with the windows on the front arranged in the typical New England pattern of four on the first floor and five on the second, revealing the transition to the houses of the second period.

Most of New Hampshire’s interesting old houses are of the second and third periods. They were built of wood from her forests, of the brick for which the State is still famous, and occasionally of native stone. Due to the abundance of timber, the use of heavy frames was continued through the third period and later, although in eastern Massachusetts such frames had disappeared before the end of the third period.

Houses of the second period often have gambrel roofs, with either three or five dormers. Variation in the façade is achieved by alternating pointed and segmental pediments over the windows. Occasionally when the front door has a pointed pediment, the dormer above it will repeat this motif, even though the pediments of the other windows are different. Representative wooden houses of this period are the Gilman-Ladd House (1745) in Exeter, the Buckminster House (1720), the John Paul Jones or Samuel Lord House (1730), and the Jacob Wendell House (1789) in Portsmouth.

The hip-roofed house of this same period had many variations. Sometimes it was with dormers, as in the Wentworth-Gardiner House (1760) in Portsmouth; or without, as in the General Moulton House (1769) in Hampton. Sometimes it was highly ornamented, as in the Governor Langdon Mansion (1784) in Portsmouth; sometimes severely plain, as in the Robert Means House (1785) in Amherst. The type possessed great flexibility in the hands of early builders.

The first brick house of the early period in the State was probably the Weeks House (1638?) of Greenland; its dark brick with black headers is reminiscent of the early brickwork in Philadelphia. Another interesting example is the Warner House (1718) in Portsmouth, which combines the best English traditions with a free adaptation to suit local needs. It is a plain gambrel-roofed three-story house of hand-made brick laid in Flemish bond, with a quaint cupola and two fine doorways. The three chimneys at the ends are integral with the walls, and between them is a square parapet. A captain’s deck with balustrade runs the entire length of the roof. Five dormers with alternating pointed and segmental pediments break the long roof expanse. The Swift House (about 1825) in Orford has brick the texture and salmon color of which rivals the best at Salem; the general proportions of its façade are excellent, especially in the three columnar entrances, the front one having a fine wrought-iron balcony above it. But the large arched window in the pediment shows the difficulty that the early builders sometimes encountered in adapting set forms to fit the New England scene.

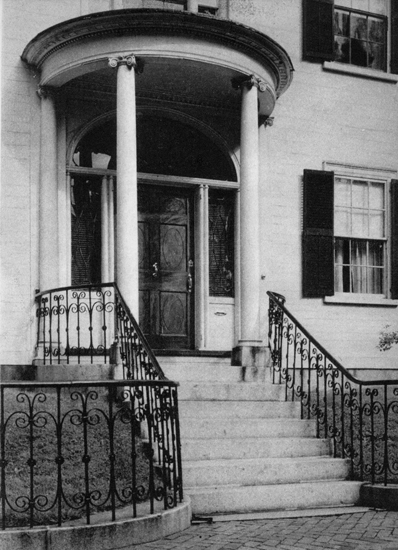

In New Hampshire, the mansions of the years from 1790 on, with their three-story façades and tall chimneys, are mainly confined to Portsmouth and Exeter. One exception is the Lord House (1822) at Effingham. That this type allowed great freedom of expression is evident from the variations in the Portsmouth houses — from the Langley-Boardman House (1805), with its gracefully rounded Ionic portico and Palladian window, through the austere severity of the brick Larkin House (1815), to the well-balanced design of the Peirce Mansion (1800). Other variations show the use of a triple terrace to give added height, or delicate iron balconies to relieve the severity of a plain façade.

Portsmouth and Exeter are outstanding as centers of noteworthy early architecture, but scattered throughout New Hampshire are small groups of houses of the early type. There are four at Park Hill on a commanding eminence above the Connecticut Valley, three frame houses and one — the earliest, the Cobb House (1800) — of brick with four chimneys. Walpole has some half-dozen frame structures of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, among them the General Allen House (1792), the Bellows House, and the especially fine Mason House (1830) on the River Road. Well back on a ridge parallel to Orford’s elm-shaded main street is a row of incomparable houses, among them the General Wheeler House (about 1820), suggesting the love of luxury and ease of their prosperous builders. Near Haverhill’s little fenced Common is another group of superb early houses, fine in design and elaborate in decoration; among these are the Hazen House (1765), the Porter House and the Colonel Johnston House (about 1770), and the General Montgomery House (1790). It should be noted that all of these groups representing the wealth and taste of the early settlers are on the eastern banks of the Connecticut River. The contrast between them and the simple early houses of the same period on the western bank in Vermont is striking. Windsor and Newbury alone have comparable groups.

New Hampshire did not take very kindly to the Greek Revival which came into vogue about 1820, but it has a few examples of the style, most of them isolated. In two places there are outstanding groups. One of these, on the main street of Alstead, consists of four frame houses with Greek Doric motifs, all apparently on the same plan with the exception of one in which a second-story porch is incorporated. Central Street in Claremont has a remarkable group of six similar houses, four of brick with wooden gables (1835–36), and across the street two frame houses of the same type — although one of these, the Swasey House, dates from 1780.

New Hampshire landscapes are dotted with hundreds of cottages of a modified Cape Cod type, with one story and a low attic, in various stages of physical condition. Many stand beside a large weathered barn which emphasizes the smallness of the house. The whole effect is of closest intimacy with the soil. These cottages are in great demand by those who wish summer residences in the State; and many of them, restored with care and taste, possess architectural merit.

Farmhouse architecture has a charm of its own in New Hampshire, not so much from perfection of design as from the grouping of the buildings. In many instances, the house and other buildings are detached; but more interesting architecturally are the examples in which they are connected. In some groups of the latter sort, there is a gradual stepping down from the house through the ell, the woodshed, the carriage shed, and the outhouse in such manner that one feels as though the whole group could be pushed together like a child’s nest of boxes. Other groups have the house in the center, with a graduated series of other buildings on each side. A few notable groupings are U-shaped, the finest example of this kind being the Daniels Homestead (1800) in Plainfield, with the house at one side, the barns at the other, and the carriage house and wood-sheds connecting them at the rear.

In common with the rest of New England, New Hampshire had no precedents to follow in its church buildings. The dominant purpose was to avoid all suggestion of the English Gothic type. The building had to serve the double purpose of church and town-meeting house. The immediate result was a spireless rectangular, gable-roofed building, prevailingly two-storied, with simple paneled doors, many windows, and little decoration. The oldest example of such a church is at Newington (1713), of which parts of the outer shell remain unchanged, although extensive alterations in 1838 ruined the interior. Two other admirable specimens are at Sandown and Danville. The exterior of the Danville church is original, and the interior was restored (largely with original material) in 1936.

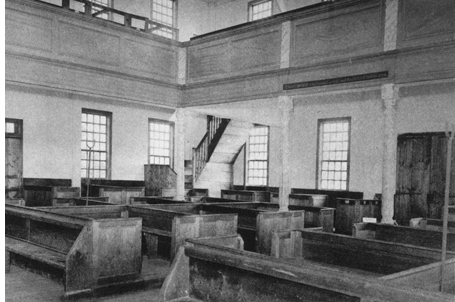

The Sandown Meeting-House is the finest early frame church structure in the State. It is a large rectangular building with three dignified doorways, two of which have different dates— 1773 and 1774 — indicating the stages in the completion of the building. The structure is notable for its large windows, containing more than a thousand panes of glass, most of them original. Decoration is confined to simple detail work in the pediments of the doorways and the cornices. The heavy doors of the main façade are paneled with oak on the outside and pine on the inside, and provided with heavy wooden bars. The interior preserves its original condition, even to the heavy-timbered free benches and slaves’ pen in the gallery. Of unusual gracefulness is the canopied pulpit, thirty feet high, of the rare wine-glass type. The only discordant note is the presence of two imitation marble pillars, but these are a century old. Wooden pegs were used in the framing, and hand-forged staples are evident in the construction of the pews.

Union Church in West Claremont represents a transitional type from box to towered structures. This church was begun in 1773, from plans provided by Governor John Wentworth — who also agreed to furnish the necessary nails and glass, but failed to keep his bargain. Only partially finished, it was first used in 1789, and the following year the interior was completed. The church is unusual for its period in having only one story, although it once had a gallery in the rear. A touch of sophistication was added in the curved windows. The interior is original, with box pews topped by a narrow spindle railing. The tower and belfry were added in 1800, and are most obviously additions, appearing as though pushed up against the original structure. The low belfry is a concession to the increasing demand, then current, for more elaboration of church buildings.

Saint John’s Church (1806) in Portsmouth is the outstanding brick ecclesiastical building of this early era. Its cupola is an architectural delight. Above the cornice of the short square tower rises a domed octagonal lantern, with eight paired Ionic pilasters supporting the dome and four arched windows between the pilasters. Resting on the pilasters is a denticulated entablature, from which the dome rises in a graceful curve to the weathervane.

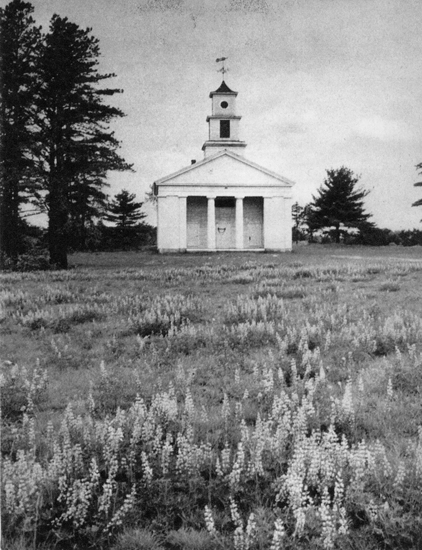

This church, however, does not represent the trend of early nineteenth century ecclesiastical architecture in New Hampshire, nor did it establish any precedent. Such architecture indicates markedly the influence which was coming into power in Massachusetts and Connecticut at this time. It is interesting to note, however, that in the southeastern part of the State the antagonism to Massachusetts was not alone political but in a measure esthetic. This led the people of that section to go on independently and retain unchanged their rectangular spireless churches. In the Connecticut Valley there was no such antagonism to the States immediately to the south; and their ideas, architectural and otherwise, were freely accepted. Furthermore, many of the settlers themselves were from Connecticut and Massachusetts towns. The material success of many of these communities in this most fertile region made it possible for them to give expression to their taste in decorated spires and other architectural embellishments. Moving on from the stage represented by the Union Church at West Claremont, their towers and spires were skillfully added to the old rectangular churches to achieve a harmonious unit.

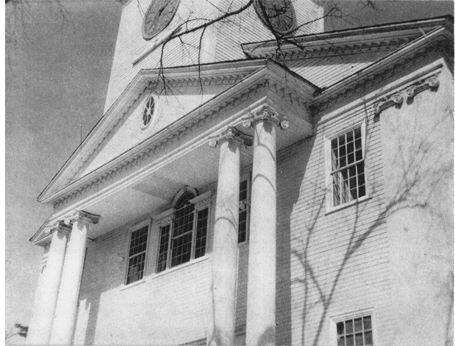

A group of this later type is in the lower Connecticut Valley, beginning at Fitzwilliam (1817), Hancock (1820), Park Hill (1824), and Acworth (1825), each in its way embodying ideas revolutionary for New Hampshire. In every case, the square towers were integrated into the body of the church building. Ionic or Tuscan pillared and pedimented porches adorn the façades. Above the tower are superimposed elements of decreasing height, an open-arched square belfry, one or more octagonal lanterns, and a surmounting weathervane. Balustrades surround each deck above the tower. Palladian windows appear in the pediments or above the doors. The decoration of entablatures and cornices is of extreme delicacy. It has been stated that ‘in the early part of the nineteenth century, architectural styles traveled up country [in New Hampshire] at the rate of about two and a half miles per year.’ The Fitzwilliam church follows the Ionic order, Acworth the Tuscan. The Acworth tower is generally rated the best in the group.

New Hampshire unfortunately fell victim to the jigsaw or gingerbread architectural style which became popular in the Victorian era. This style seems traceable to the perfection of wood-working machinery in the middle of the nineteenth century, and to a restless but futile desire for beauty in a people who had no indigenous culture. Some interesting examples of the phase are the Sawyer Mansion at Dover, the French House at Portsmouth, and a number of houses at Littleton.

As ‘the Granite State,’ it seems natural to expect that New Hampshire should make considerable architectural use of the stone for which the State is famous. But except in scattered houses and late public buildings and churches, the use of granite is largely confined to the southeastern section of the State, where it appears in numerous houses, and in one fine mill at Newmarket. In the very heart of the quarrying section at Concord, only a few granite houses and one mill, at Penacook, the northern ward of the city, may be found. It is remarkable that granite has not been more commonly used, but the time and expense of preparing it for building purposes have evidently been too great for thrifty New Hampshire.

Two educational centers are of interest architecturally. At Hanover, Dartmouth Hall, a long three-story brick building, was erected in 1935–36 to replace a wooden structure of 1791, the original lines of which were closely followed. There is a simple dignity in the façade broken only by a pedimented section thrust forward in the center. The delicate detail of the late Colonial cupola and a somewhat elaborated cornice relieve the severity of the building as a whole. The long red-brick Baker Memorial Library was designed as an architectural focus for the Dartmouth College campus. Of simple Colonial-Georgian design, it is dominated by a fine central porch, above which rises a low brick tower, supporting a white wooden clock tower with the corner posts treated as Ionic pilasters. From this rises an open-arched octagonal lantern, which in turn supports a slender spire dominated by a weathervane. The whole steeple, strongly suggestive of that at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, is accented by large urn-finials on the posts of the balustrades that surround each section. This memorial library was built in 1928 through the generosity of George Fisher Baker, from plans by Jens Frederick Larson. Sanborn House and Carpenter Hall are so integrated with the library as to form a pleasing unity.

Phillips Exeter Academy at Exeter is most fortunate in having Ralph Adams Cram, a native of near-by Hampton, as its architectural adviser. It was from his designs that the simple Gothic, English-type, stone Phillips Church, now a part of the Academy group, was built in 1897. The Davis Library (1911), also designed by him, is rich in ornament, recalling Christopher Wren’s work at Hampton Court in England. The Academy Building (1794) was destroyed by fire in 1870. Mr. Cram reproduced it in 1914 with a certain fidelity and with the delicacy associated with the best Colonial design, combined with a dignity proper to its position and function. The belfry deserves high praise. In 1925, Amen Quadrangle was constructed after Mr. Cram’s designs, and two other quadrangles designed by him were built in 1930 and 1933. A number of other single buildings on the campus are of his creation.

Town planning in New Hampshire was largely a matter of necessity. The houses of settlers were built in a compact group or within a short range along a single street. Back from the houses, each settler had farm land in amount sufficient to maintain his family. This compactness made defense easier, and communal interests were more effectively maintained.

When mills came into the larger centers, housing conditions for the workers required the building, generally by the owners of the mills, of a large number of inexpensive frame houses. Such housing groups are to be found in Keene, Somersworth, and Berlin. Manchester has a notable group of mill houses erected by the Amoskeag Company about 1870. Built on sloping banks, the long rows of connected brick buildings avoid monotony by being staggered. A further variation is the placing of some of the units at right angles to the prevailing lines.

Mill architecture in New Hampshire had its beginning in the lean-to sawmill or gristmill operated by some adjoining stream. Early mills of this type are now jumbled masses of decaying lumber, if they remain at all. At Bow is a mill with an up-and-down saw, housed in a long and low weathered structure, which has been in active use since the early 1800’s. Other early mills of architectural interest include one of brick at Exeter, one of stone at Newmarket, and one at Shaker Village in Enfield in which the stone is not only cemented but fastened by iron dowels.

Among the master builders or architects associated with New Hampshire, the Whiddens, father and son, worked in Portsmouth, Crehore at Walpole. William Durgin, builder of bridges and churches, lived in Sanbornton. Charles Bulfinch, who is reputed to have designed the Wheeler House at Orford and the Unitarian Church at Peterborough, seems to have cast his influence in neighboring towns along the Connecticut, as well as in Portsmouth on the seacoast. Even the influence of Asher Benjamin, who set a notable example of domestic architecture at Windsor, Vermont, across the Connecticut River, must have been felt on the New Hampshire side.

An atmosphere of serenity pervades such old towns as Amherst and Haverhill, with their shaded greens and well preserved buildings. Almost as restful are the towns laid out along a highway — as for example, Orford, with its double rows of arching elms and back on the ridge a row of beautiful houses suggesting luxury and comfort. The lover of architecture cannot soon forget the charm of Exeter’s early homes. Portsmouth presents several aspects — the elegance of a few remaining streets of noble residences, and the picturesqueness of the older town near the water, with its winding streets and weathered houses. To come suddenly upon the splendid groups at Park Hill and Lord’s Hill is a memorable experience. New Hampshire rewards the traveler who responds either to the formal or to the picturesque in architecture.

![]()

![]()

NEW HAMPSHIRE architecture runs the gamut from the little story-and-a-half cottage under a great protecting elm to the stately mansions of Portsmouth; from the demure, modestly towered church by the roadside to the graceful and ornately spired meeting-house, a landmark for miles. San-down’s wine-glass pulpit looks down on original pews occupied in 1773. The First Church in Walpole is typical of many in compact centers, while the church in South Merrimack is one of dozens that seems to sit in loneliness and rusticate apart from human activity. The Wheeler House in Orford is a specimen of the beautiful late Colonial country houses found along the New Hampshire side of the Connecticut River.

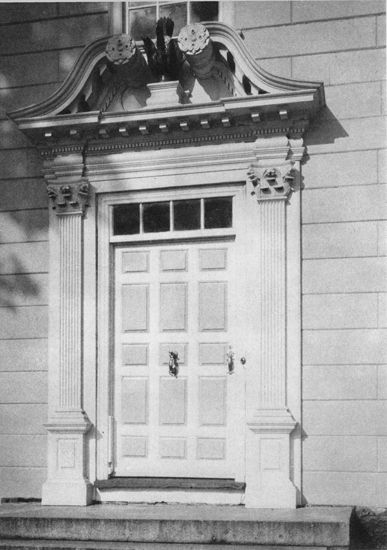

Ornamentation was a fine art in the early nineteenth century as evidenced by the two church spires. For the highest examples of exterior and interior ornamentation, however, one must go to Portsmouth where the architect and woodcarver had full opportunity. A few specimens are given here.

PULPIT IN MEETING-HOUSE (1773), SANDOWN

INTERIOR OF MEETING-HOUSE, SANDOWN

PORCH, LANGLEY BOARDMAN HOUSE, PORTSMOUTH