![]()

![]()

Town: Alt. 30, pop. 4872, sett. 1638, incorp. 1638.

Railroad Station: B. & M. R.R., Lincoln St., 0.5 m. west from center of town.

Bus Stations: B. & M. Transp. Co., R.R. Station, Thompson’s Drug Store, 107 Water St.; Interstate, Thompson’s Drug Store.

Taxis: 25¢ per mile.

Traffic Regulations: Observance of stops rigidly enforced. Two hr. parking on Water St.; all night parking on streets forbidden.

Accommodations: Three hotels.

Tourist Information Service: Chamber of Commerce, 107 Water St.

Amusements: Concert Hall, Phillips Exeter Academy, Front St., free musicales, Sunday evenings, during the fall and winter seasons; one motion-picture theater.

Swimming: Exeter River above the dam.

EXETER is an old Colonial town among low, rolling hills, the home of Phillips Exeter Academy, preparatory school for boys. Its winding elm-shaded streets, its dignified white houses, and its Academy buildings give it a serenity in sharp contrast to the stirring and perilous days of its early history. Exeter, always sufficient unto itself, is still imbued with that spirit of independence which made it a hotbed of patriotic activity during the days of the Revolution.

Ten miles east of Exeter are the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. When the wind is ‘in the east,’ the tang of the sea is strong. This has given Exeter somewhat of the spirit of Gloucester or Marblehead, which is also evident in the architecture and the arrangement of the streets.

Settled in 1638 and antedated in New Hampshire only by settlements at Dover and Portsmouth, Exeter sprang up by the falls of the Squamscott River and grew around the personality of the Rev. John Wheelwright, a political and religious outcast from Puritanic Boston. He was a graduate of Cambridge University and a fellow collegian of Oliver Cromwell, who afterward said that he was more afraid of meeting Wheelwright at football than he had been since of meeting an army in the field, for he was infallibly sure of being tripped up by him. A brother-in-law of Anne Hutchinson, who was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony because of her radical religious views and who fled to Rhode Island, Wheelwright’s non-conformity was apparently his only sin.

Since land travel was very difficult, Wheelwright undoubtedly came by water to the settlement at Strawberry Bank (Portsmouth) and through the wilderness to the site of Exeter. It is thought that he stayed through the winter with Edward Hilton, one of the settlers of Dover, who had moved to neighboring territory. At the first signs of spring, Wheelwright secured a deed from Wehanownowit, Sagamore of the Squamscott tribe, who owned the land in the vicinity of Exeter, and Primnadockyon, his son. This deed is preserved at Exeter Academy and reads:

Know all men by these prsents yt I Wehanownowitt Sagamore of Puschataquake for a certajne some of money to mee in hand payd & other mrchandable comodities wch I haue reed as likewise for other good causes & considerations mee yr unto spetially mouing haue granted barganed alienated & sould vnto John Wheelwright of Pischataqua & Augustine Storr of Bostone all those Lands woods Medowes Marshes rivers brookes springs with all the apprtenances amoluments pfitts commoditys there unto belonging lying and situate within three miles of the Northerne side of ye river Meremake extending thirty miles along by the river from the sea side & from the sayd river side to Pischataqua Patents thirty Miles vp into the country North West & soe from the ffalls of Pischataqua to Oyster river thirty Miles square evry way, to haue & to hould the same to them & yr heyres for euer only the ground wch is broaken vp is excepted & it shall bee lawful for ye sayd Sagamore to hunt fish & foule in the sayd lymitts. In witness wrof I have hereunto sett my hand & seale the third day of Aprill 1638.

The first year saw few settlers except Wheelwright’s family and a few loyal parishioners from Boston, who organized the first church with Wheelwright at its head. The settlement grew and in 1642, upon petition ‘to the Right Worshipful Governor,’ Exeter was admitted with the three other New Hampshire settlements to the sovereignty of Massachusetts. Wheelwright fled to Wells, Maine, to escape the jurisdiction of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but later was pardoned and returned to preach in Hampton.

Exeter supported the New Hampshire Provincial Government that was set up in 1680, but in 1682, when Royal Governor Cranfield sent his marshal to collect taxes without the consent of the Assembly, he was informed by the leading women of Exeter that ‘a red-hot spit and scalding water’ were ready for him, and he returned home with his purse as empty as when he came. From 1686 to 1690, New Hampshire was without formal government. When reunion with Massachusetts was renewed from 1690 to 1692, Exeter, along with other settlements, acknowledged the necessity of a recognized governmental authority and gave allegiance to the Bay State.

As a frontier town Exeter suffered during the French and Indian wars. Although there was no general attack upon the town, her citizens gained military experience in their fights with the Indians.

Exeter’s defiant attitude toward ‘Royal Commands’ never abated and was shown in the Mast Tree Riot of 1734 against the practice of marking the best trees for the Royal Navy. Believing that the men of Exeter were cutting these trees for their own use, David Dunbar, surveyor general for the Crown, sent ten men to set the King’s mark, a broad arrow, on any trees he might find at the Exeter mill. A group of Exeter Colonials dressed as Indians dragged the men from their beds in Samuel Gilman’s tavern and hustled them out with threats and blows. The ‘unlucky wights’ found their boat scuttled and their sails destroyed and had to return to Portsmouth as best they could.

Around the little village of Exeter centers more of interest touching the struggle for American liberty than any town in the State. In January, 1774, the town resolved that, ‘we are ready on all necessary occasions to risk our lives and fortunes in defence of our rights and liberties’; and two British ministers, Lords North and Bute, were burned in effigy before the jail.

In 1775, the capital was removed to Exeter from Portsmouth, there being too many Tories at Portsmouth, while Exeter was almost wholly Revolutionary. The first Provincial Congress met in Exeter, July 21, 1774, and several sessions were held in the town in the next year. They alternated with the Committee of Safety, so that one body or the other was sitting continuously. The first of the Provincial congresses assembled December 21, 1775, and ‘took up government’ by resolving itself into a house of representatives and by adopting, January 5, 1776, a written constitution. By this act New Hampshire became an independent colony. Seven months later a messenger brought the Declaration of Independence, which was read to the people by John Taylor Gilman, afterward Governor of the State for fourteen years. Exeter was then the center of the State’s activity — civil, legislative and military. The town ran riot with patriotism and in all the village there was but one downright Tory, the town printer, who afterward was imprisoned for counterfeiting the provincial currency. He escaped, however, and fled within the British lines. From 1776 to 1784 the sessions of the State Legislature, with few exceptions, were held in Exeter.

When George Washington came through the almost primeval woods from Portsmouth in 1789, he wrote: ‘This is a place of some consequence but does not contain more than 1000 inhabitants. A jealousy subsists between this town, where the Legislature alternately sits, and Portsmouth which, had I known of it, in time, would have made it necessary to have accepted an invitation to a public dinner.’

Fishing, lumbering, and cattle-raising were the first industries. In 1795, Joseph Scott wrote of Exeter in his volume, ‘The United States Gazeteer,’ ‘Here are also ten grist mills, a paper mill, a fulling mill, a slitting mill, a snuff mill, two chocolate and six saw mills, iron works, a printing office and a duck manufactory which was lately established. Previous to the Revolution this town was famous for ship building but latterly it has been much neglected.’

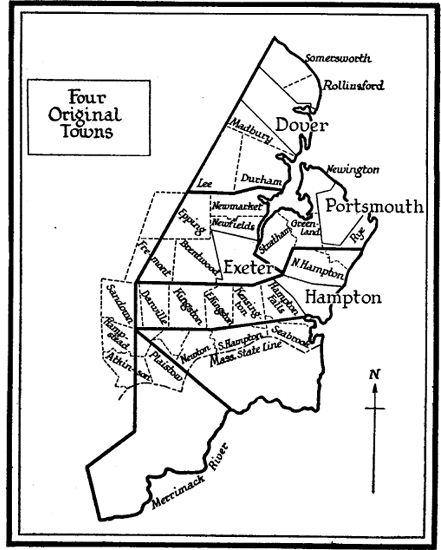

In time Exeter’s territory, which, according to the Indian agreement, covered about four hundred square miles, was reduced to about seventeen square miles, the towns of Newmarket (1727), Epping (1741), Brentwood (1742), and Fremont (1764) having separated from it and set up their own housekeeping.

Although Exeter is largely residential and academic, it has several industries manufacturing cotton, brass, and marble products, shoes, and building materials.

SW. from Water St. on Front St.

1. The Bandstand, cor. Water and Front Sts., a circular pavilion of great dignity, with a pointed roof supported by simple Doric columns, was designed by Henry Bacon, architect of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. This was given to the town in 1913 by Ambrose Swazey, Exeter’s chief benefactor. Tradition records that when the town meeting was discussing the proposed acceptance of the gift, one voter with true Yankee spirit moved that the offer be rejected, as he didn’t hold with any man’s giving so much money outside of his family.

2. The Town Hall, NW. corner of Water and Front Sts. (R), was built in 1855. An impressive structure of brick, topped with a white cupola, it is a good example of the architecture of the period. The granite walls of the basement are a much later addition.

3. The George Sullivan House (not open), 4 Front St. (L), a three-story mansion, with a lavishly adorned doorway, a finely denticulated cornice, and window caps, formerly the home of George Sullivan, son of General John Sullivan of Revolutionary fame, is the first of a row of three similar houses, that give an atmosphere of quiet dignity to the street.

4. The Gardner House (not open), Front St. (L), with a plain square porch with Doric columns, a finely denticulated cornice, and reeded window caps, is the second of these three houses. This was built in 1826 and was held in the same family for three generations.

5. The Home of Dr. William Perry (not open), Front St. (L), of simpler design, lacking any elaboration of doorway or windows, completes the series. Dr. Perry had an office here in 1814 and was adventurous enough as an undergraduate to take a trip down the Hudson in Fulton’s steamboat.

6. The Congregational Church, Front St. (R), built in 1798, is unique among New Hampshire churches in the treatment of the front façade. The four groups of pilasters are separated in each of the two stories, making each story a separate entity. Those at the second story support a lavishly decorated cornice. The short steeple, composed of a tall octagonal belfry with open arches, and a domed octagonal lantern, rises from the main roof of the entire structure. In the earlier church antedating this the General Court was sitting in 1786 when insurgents from the western towns of the county arrived to dragoon the legislature into a fresh issue of paper currency. They surrounded the church and held the legislature captive all day. At nightfall a ruse was planned by Colonel Nicholas Gilman to secure their release. A high fence prevented the besiegers from seeing what went on outside the churchyard, and in the dusk Colonel Gilman collected a small number of men, who, while a drum was briskly beaten, approached the church with a military step. ‘Hurrah,’ cried the astute Gilman, ‘here come Hackett’s artillery!’ The crowd took up the cry and the rebels vanished.

7. The Nathaniel Gilman House (open daily, 9–5), cor. Front and Elm Sts. (L), a large white house with a gambrel roof hipped at one end showing a later alteration, was built in 1740, and was restored by its present owner, Phillips Exeter Academy. The front façade has a simple doorway with a gracefully leaded fan-light, and a finely denticulated cornice. The wide hall, with dadoed walls and deeply cut paneling, has a staircase of pleasing lines. Many of the upper rooms are wainscoted.

8. The Benjamin Clark Gilman House (not open), 39 Front St. (R), has the same simple elegance and dignity of line as the Nathaniel Gilman House, which it resembles, but its doorway is slightly off center.

9. Phillips Exeter Academy, Front St. (R and L), is Exeter’s central attraction, its dignified brick buildings having an unaffected charm well suited to an old academy nestling under the elms of a still older New Hampshire village.

John Phillips, from whom the Academy takes its name, was a native of Andover, Massachusetts. A graduate of Harvard at sixteen, he trained for the ministry, although he never engaged in it. Coming to Exeter in 1741, he taught school for a time, but trade attracted him more and he succeeded admirably in it. In his later years he became a benefactor of education. Dartmouth College in its first years received his aid. In 1778 with his brother Samuel, he founded Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. Later he cherished a plan of establishing an academy in his own town. Phillips Exeter Academy was made possible by his benefactions and was opened in 1783 with William Woodbridge, as principal, followed by Benjamin Abbot, whose scholarship and executive ability established the standards that succeeding principals have maintained.

The Academy is a college preparatory school having an enrollment of 700 students. It is amply endowed, and the recent gift of Edward S. Harkness makes possible the conference method of instruction with an instructor for every 12 boys.

In the Academy’s century and a half of existence the list of graduates who have risen to the highest rank is an imposing one. Three Presidents have sent their sons to Exeter: Lincoln (Robert), Grant (Ulysses, Jr.), and Cleveland (Richard and Francis).

The Yard (R), the oldest part of the Academy property, was given by Governor Gilman in 1795. Here are the Older Dormitories, their barrack-like severity indicating the austerity of student life in the nineteenth century; the Academy Building, combining Georgian Colonial tradition with dignity proper to its function as the school chapel; Alumni Hall, of massive construction and classical design, reminiscent of the English college commons; and Phillips Church, built of stone in simple Gothic style.

Dormitories and Classroom Buildings, built since 1925 around two quadrangles behind the Academy building, and the other buildings erected since 1907, were designed by Ralph Adams Cram, architect of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. The characteristic features of these later dormitories are the general simplicity of design, the gambrel or hipped roof, a succession of windows with rounded pediments in the first floor, and small dormers in the roof, all with uniformly small panes of glass and wide muntins. The occasional accent is effected by a gable, a pavilion, or a second-floor balcony.

The Principal’s House (L), a fine three-story house with a hip roof, is set far back from the street under wide-spreading trees. Built in 1811, it was originally a two-story house of simple Colonial design. Around it are some of the newer dormitories, the library, the physical education group of buildings, and the playing fields.

R. from Front St. on Tan Lane

10. The Faculty Club (not open), Tan Lane (L), a very small two-story structure with a hip roof, combines its almost miniature proportions with great skill. Severely plain in every detail, its charm comes from the harmony of its proportions. Erected in 1783 as the first academy building, it originally housed all the school activities. It was recently restored by Ralph Adams Cram.

Retrace on Tan Lane; R. from Tan Lane on Front St.

11. The Edward Tuck Birthplace (not open), 72 Front St. (L), a small two-story white house with a pitched roof and a large central chimney, is set behind a white picket fence. It was built in 1750 and is owned by the Academy. Edward Tuck, born here in 1842, founded the Amos Tuck School of Administration and Finance at Dartmouth College and contributed to many other institutions.

R. from Front St. on Lincoln St.

12. Robinson Seminary, Lincoln St., housed in a brick building typical of the 1870’s, was founded in 1867 through the bequest of William Robinson, a native son who had acquired a fortune during his life in Augusta, Georgia. This made possible the founding of a female seminary where ‘the course of instruction should be such as to make female scholars equal to all the practical duties of life; such a course of education as would enable them to compete, and successfully, too, with their brothers throughout the world, when they take part in the actual duties of life.’ This principle has been successfully maintained through the decades, and this school offers its facilities, gratuitously, to the girls of Exeter. The Seminary has 350 students from Exeter and neighboring towns.

Retrace on Lincoln St.; R. from Lincoln St. on Front St.

13. The Soldiers’ Memorial, cor. Front and Pine Sts., depicts an idealized soldier in overseas uniform under the sheltering arm of a guardian angel represented by a statuesque female with flowing drapery and an olive branch in her hand. It was executed by a native, Daniel Chester French (1850–1931). The group is cast in bronze, and stands in a small landscaped plot.

14. The Home of Henry A. Shute, 3 Pine St. (L), is known to countless readers because his ‘Real Diary of a Real Boy’ was written here. Between 6 and 27 Court St. (L. from Pine St.) is the locale of these stories by Judge Shute, for in this section were the homes of ‘Plupy,’ ‘Beany,’ and ‘Pewt.’

TOUR 2 — 0.5 m.

E. on Water St.

15. The Gilman-Clifford or Garrison House (not open), cor. Water and Clifford Sts. (R), is the second oldest, if not the oldest, building in New Hampshire. The main part of this rambling, red ‘wooden castle’ was built between 1650 and 1658 by Councillor John Gilman and was designed to thwart Indian attack. The upper story projected a foot or more beyond the lower. This overhang is visible at the back of the house. The windows were hardly more than loopholes and the door had a portcullis that could be instantly dropped. A small portion of the wall is stripped to the original timber to show the joining of the square logs.

The front wing, which projects toward the street, was added by Brigadier General Peter Gilman in 1772 to provide a proper place of entertainment for Governor John Wentworth and his staff. The interior of these rooms is distinguished by paneling and elaborately carved woodwork. The Royal Governor liked to visit a battalion he had formed at Exeter called the ‘Cadets,’ whom he had brilliantly uniformed and equipped and of whom he was very proud, although they repaid his courtesies by taking his weapons and marching away to Cambridge as soon as they heard of the affair at Lexington. John Phillips, founder of Phillips Exeter Academy, was colonel of the corps.

While a student at the Academy in 1796, Daniel Webster boarded at this house with the family of Ebenezer Clifford, a noted woodworker who made the paneling in the old room, now displayed in the Metropolitan Art Museum of New York. The youth’s crude table manners often shocked Clifford, but knowing that the boy was sensitive he was reluctant to correct him. Instead, Clifford fell upon the scheme of reproving the apprentice of his shop, who in the homely fashion of the time sat at the same table, for the same faults and was relieved to see the quick-witted young Webster mend his table etiquette accordingly.

L. from Water St. on High St.

16. The Boarding-Place of Robert Lincoln (not open), cor. High and Pleasant Sts. (L), is a two-story brick house with a store on the ground floor, joined at the left side to another brick house having its front façade curved to fit the bend in the street. Here Abraham Lincoln visited his son while the latter was a student at the Academy.

The junction of the streets at this point forms Hemlock Square, so named from the time the militia trained in the Square in the 17th century, when in rainy weather hemlock boughs were strewn over the ground to cover the mud.

17. The Fields House (not open), 25 High St. (R), a small two-story house with a hip roof and a lofty chimney on either end, is one of the most charming of the Exeter houses. The front façade contains a simple doorway with an elliptical fan-light. At one time an elderly gentleman named Coffin Smith lived here. He had three sons and three daughters, all of whom married and settled in Exeter. Tradition relates that every morning Mr. Smith made a round of calls on his six children to find which one had the most appetizing dinner menu. He would then invite himself to the meal that pleased him best.

18. The Tenney House (not open), 65 High St. (R), an imposing three-story residence with a pedimented central section and a two-story wing on either side, is different from any other house in this region and resembles the mansion of an English country manor much more than other New Hampshire houses. The front doorway carries a heavy pediment, and massive caps top the windows of the lower story. The hip roofs of the two wings are surrounded by a latticed balustrade, and from each of them rises a tall, rugged chimney. This house was built in 1798 by Dr. Samuel Tenney, who served as a surgeon at Bunker Hill and at Yorktown. His wife, Tabitha Gilman, author of ‘Female Quixotism,’ was the earliest woman novelist in America. It is related that the doctor and his wife, while planning their house, drove around the countryside in their chaise looking for a model. The source of their final inspiration is not known. Originally this house stood on Front Street, where the Courthouse now stands, and the feat of moving it across the river seems almost impossible.

TOUR 3 — 0.2 m.

W. from Town Hall on Water St.

19. The Gilman-Ladd House (open on application to the caretaker: free) (L), cor. Water and Governor Sts., now the chapter house for the New Hampshire Cincinnati, a slightly asymmetrical two-story house with three dormer windows piercing the pitched roof, has two front vestibules, indicating a later wing. Built in 1721 by Nathaniel Ladd, it passed into the hands of the Gilman family 30 years later and became the dwelling of several famous men, including Nicholas Gilman, Jr., a signer of the Constitution. The original house of brick was later expanded into the present rambling structure and covered with wood. The interior is finished with deep window seats, paneled wainscoting, and huge fireplaces.

The Ladd family is an old one in Exeter. An earlier Nathaniel Ladd sounded the trumpet in Gove’s Rebellion against Governor Cranfield (1682–85) and was afterwards killed in a battle with the Indians. Simeon Ladd, three generations later, according to historian Bell, was president of a society of choice spirits called the ‘Nip Club,’ which used to assemble at one of the taverns for convivial purposes. His eccentricity may have been inherited from his father, who kept a ready-made coffin in his house to meet an emergency, and invented a pair of wings which he fondly believed would enable him to cleave the air like a bird, until he tried the experiment from an upper window.

More staid, and also more distinguished, the Gilman family gave two governors to the State and a Senator to Congress. From the ‘treasury room’ at the left of the main entrance Nicholas Gilman, treasurer of the Colony, issued all New Hampshire’s Colonial currency during the Revolution, and many a night he sat armed in his office, expecting a British attack. Governor John T. Gilman, another member of the family, lived to a ripe old age in this house. According to tradition, on the night before his death he was brought downstairs by a Negro servant to enjoy for the last time the company of his family. Realizing that his time was nearly spent, he gave full oral instructions about his burial and the manner in which he wished to be remembered, insisting that his family should not wear mourning for him. ‘Spend upon the living, not the dead,’ he said. A few minutes later, feeling very tired, he left the room, remarking, ‘I have no disposition to leave this precious circle. I love to be here surrounded by my family and friends.’ Then he gave them his blessing and said, ‘I am ready to go and I wish you all goodnight.’

20. The Folsom Tavern (not open), cor. Water and Spring Sts. (L), a large, Georgian Colonial house with a hip roof and a pedimented doorway, is also owned by the New Hampshire Chapter of the Cincinnati. At present, the small panes are missing from the lower sashes of the windows, but restoration of the house is being undertaken by the chapter. It was erected by Colonel Samuel Folsom in 1770, and moved from its original site on the corner of Front and Water Sts. a few years ago. In 1789 George Washington, then on a visit to New Hampshire, was entertained here.

21. The Swazey Parkway, entrance on Water St. (R), is a beautifully landscaped drive along the Squamscott River, from which is visible on the opposite bank the little square brick Powder House with its peaked roof, built in 1771 on the eve of the Revolution to house the town’s stock of powder.

TOUR 4 — 1.5 m.

W. on Water St.; L. from Water St. on Main St.; R. from Main St. on Cass St.

22. The Birthplace of Lewis Cass (not open), 11 Cass St. (R), with its gable end to the street, was built in 1740, and was the home of Major Jonathan Cass. His son Lewis (1782–1866) was a noted soldier and statesman, Governor of Michigan Territory from 1813 to 1831 and afterward Secretary of War.

23. The Odiorne House (not open), 25 Cass St. (R), a two-story house with a high gambrel roof, a simple pedimented doorway, and a small wing on the ground floor, once fitted up as a store, was built in 1735 by Major John Gilman, whose military exploits included an escape from the massacre of Fort William and Mary in 1757. Major Gilman was handsomely equipped for this expedition if we may judge from his ‘Inventory of cloaths, &c., Taken by the Indian’ that he filed with the legislature and for the loss of which he collected £300. From this inventory it appears that an officer taking the field in those days carried with him a two-volume Bible, a wig, glass and wooden bottles, gold-laced hats, coats, waistcoats, jacket, great-coats, gowns, sermon book, ivory book, and dozens of articles that would puzzle the modern soldier. Major Gilman had 12 children, and one daughter married Deacon Thomas Odiorne, who built the little store on one side of the house.

L. from Cass St. on Park St.

24. Giddinge’s Tavern (open on application to owner), cor. Park and Summer Sts. (R), a square, hip-roofed house with large overhanging eaves, was built in 1724. The front door, four panels wide, is one of the widest in Exeter. A large millstone serves as a door step. This tavern was built by Zebulon Giddinge, who catered to the loggers hauling logs to the river. In the tense days before the Revolution, it was used as a meeting place by the Exeter patriots.

25. The Jeremiah Smith House (not open), 77 Park St. (R), a gambrel-roof house with pedimented dormer windows and capped windows on the lower floor, formerly had a notched square porch over the front door. A tall chimney rises at either end. This house, built in 1750, was the home of Judge Jeremiah Smith, a soldier in the Revolutionary War, Governor of New Hampshire, 1809–10, and Chief Justice of the State.

L. from Park St. on Epping Rd.; R. from Epping Rd. on Winter St.

26. The Leavitt House (not open), 91 Winter St. (R), a long, rambling mansion with beautiful woodwork, built in 1740, was at one time a tavern, later an establishment where stovepipe hats of fur and plush were made. It was also the headquarters of the ‘White Cap Society.’

In 1797, this society was formed by a sharper from New Jersey, Rainsford Rogers, to dig for buried treasure, the whereabouts of which he claimed to know because of his power over evil spirits. On dark nights he repeatedly conducted the members, among them many prominent citizens, to out-of-the-way places to dig in the swamps, instructing them to wear white caps on these expeditions. On one of these nocturnal excursions there appeared before the eyes of the awe-stricken diggers a figure all in white, representing a spirit, which uttered some words which were not well understood. One of the ‘white caps,’ anxious to lose nothing of the weighty communication, responded, ‘A little louder, Mr. Ghost, I’m rather hard of hearing!’ Dig as they might, they reached no treasure. Rogers said what they needed was a divining rod costing several hundred dollars. The deluded company raised the money and delivered it to the sharper, who mounted his horse, and, with a saddle and bridle borrowed from one of his dupes, rode off to parts unknown, never to return.