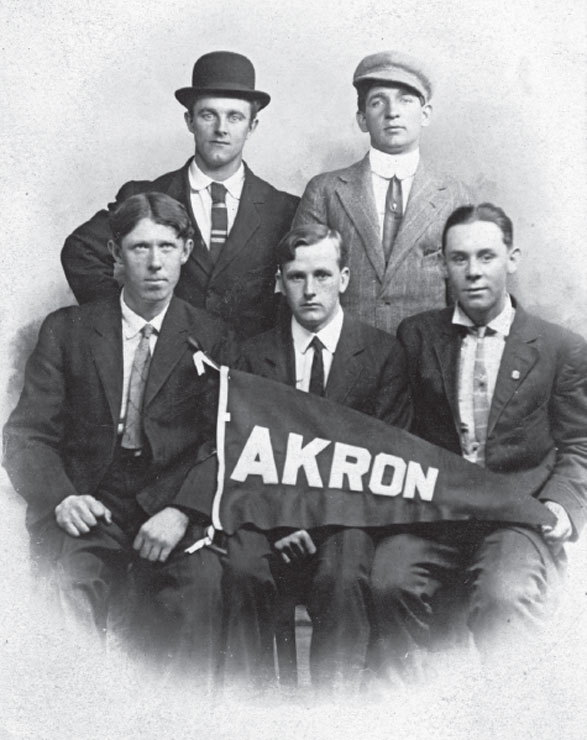

Newcomers to the “City of Opportunity” pose for a souvenir portrait in the early 1900s at Arcade Studio on South Howard Street. The backdrop resembles the Akron Limited train. Author’s collection.

The first thing that visitors noticed about Akron was the smell. A thick, pungent cloud of sulfur hung low over the Ohio city, an acrid fog that made nostrils flare and eyes sting. It was a gray, grimy town with billowing smoke, drifting soot and lingering haze. Yet people couldn’t wait to go there.

In the early twentieth century, Akron was a boomtown where jobs were plentiful, opportunities were bountiful and fortunes were attainable. Newcomers arrived every day to claim their stake.

Thanks to the surging popularity of automobiles, Akron tire makers Firestone, General, Goodrich, Goodyear, Miller and dozens of other rubber companies were noisy, bustling operations that operated twenty-four hours a day but still couldn’t meet demand. They needed to expand factories, boost capacity and add products, and to get it all done, they needed to hire more workers—and quickly.

Akron companies took out classified ads in newspapers across the nation, practically begging for help:

Wanted at once: 100 intelligent and able-bodied men. Apply to the B.F. Goodrich Co., Akron, Ohio.

Wanted: Good strong, reliable men for factory work. Steady employment, good wages. Write or apply to Employment Office, Firestone Tire & Rubber Co., Akron, Ohio.

Wanted: Unskilled men for production work. Ages 18 to 45. Weight 140 pounds or more in good physical condition. Good living wage paid while learning. Steady work assured. Apply in person or communicate with Factory Employment Office, the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., Akron, Ohio.

Newcomers to the “City of Opportunity” pose for a souvenir portrait in the early 1900s at Arcade Studio on South Howard Street. The backdrop resembles the Akron Limited train. Author’s collection.

Out-of-state laborers and foreign immigrants flocked to Akron, quickly landed factory jobs and wrote home to notify their friends and relatives that the Rubber City was still hiring. The Akron Chamber of Commerce proudly hailed the community as the “City of Opportunity,” a promotional slogan that was plastered on a giant billboard that welcomed railroad passengers at Union Depot.

Founded in 1825 as a village on the Ohio & Erie Canal, Akron was not quite a century old. Its early industries included clay products, farming equipment and breakfast cereal before Dr. Benjamin Franklin Goodrich of New York moved to Akron in about 1870 to open the first rubber company west of the Alleghenies. No one in the village of ten thousand could predict that pliable rubber would cement the future. When F.A. Seiberling and his brother C.W. Seiberling co-founded Goodyear in 1898 and Harvey Firestone established Firestone in 1900, Akron’s reputation as the “Rubber Capital of the World” was secure.

The sulfur-infused stench of smoking factories was hailed as “the smell of jobs.” In less than a decade, the old canal town had transformed into a major industrial city. Its rubber factories expanded from 22,000 workers in 1910 to more than 70,000 in 1920. At the same time, Akron’s population swelled from a svelte 69,067 to a stout 208,435, making it the fastest-growing city in the United States.

Frankly, there was no place to put all those people. Contractors slapped together houses as quickly as possible. Families rented out basements to strangers. Shanties sprouted on the outskirts of Akron. Rooming houses offered beds in shifts, forcing three rubber workers to take eight-hour turns.

Workers skipped town if they couldn’t find decent places to live. Goodyear and Firestone aimed to resolve the problem by building affordable homes for workers and their families in the new residential developments of Goodyear Heights (1913) and Firestone Park (1916).

Longtime residents were pleased to see their city’s prosperity in the early twentieth century, but many were alarmed by the rampant growth, which put a strain on housing, sanitation, utilities and infrastructure. As Akron historian Karl H. Grismer (1896–1952) noted, the seismic change was not entirely welcome:

Most displeasing of all were the crowds which now surged madly through the city. Never before had Akron seen so many people. Like a rampaging colony of ants, they filled the streets and sidewalks and choked the streetcars, theatres and restaurants—even in churches. Everywhere there were crowds—pushing, milling crowds, often fighting crowds. Almost every day, it seemed, the crowds became larger.

Akron’s flag flies proudly in this Arcade Studio portrait from 1912. The city’s population grew from 69,067 in 1910 to 208,435 in 1920 as laborers sought jobs at rubber factories. Author’s collection.

As strangers flooded the city, Akronites were bewildered to hear a cacophony of foreign languages and unfamiliar accents, perhaps forgetting that it was only a few decades earlier when nearly one-third of the city’s population spoke fluent German. The town was not immune to xenophobia, and foreigners were often viewed with distrust and disrespect. By 1915, as the Great War raged in Europe, Akron was home to an estimated 4,500 Serbians, 4,000 Hungarians, 3,500 Italians, 3,000 Romanians, 2,000 Slovaks, 1,500 Austrians, 200 Armenians and thousands more from miscellaneous ethnicities—truly a melting pot.

The Akron YMCA held Americanization classes at night to help the newcomers assimilate but found it challenging to weld such disparate groups into one nationality. Many did not speak English or understand local customs. Urging Americans to try to better understand foreigners, immigration expert Edward A. Steiner, a professor at Grinnell College in Iowa, praised the YMCA’s efforts in a 1916 lecture at the First Methodist Church in Akron:

We get the pick of the men from foreign lands. They must pass physical examinations before they can buy a ticket. At Ellis Island, they must undergo still more stringent tests, more searching than we would have to face for life insurance. The men are fine specimens. They come to us abounding in health and youth and vitality and energy. How do we treat them? We give them the hardest, the most dangerous, the dirtiest work to do. They see the saloon and the poolroom, the women of the street, the unscrupulous employment agencies. They often miss the real America.

There was no test for malevolent intentions, though. Besides attracting hardworking laborers, Akron also was the “City of Opportunity” for criminals, connivers and crooked characters. Young factory workers, new to town, had money to spend—and there was no shortage of ways to spend it. Gambling parlors, billiard halls, unlicensed saloons and houses of ill fame lurked in shady corners of town.

Criminal arrests nearly doubled in Akron from roughly 5,900 in 1915 to about 10,600 in 1916. Safety Director Charles R. Morgan urged the public to help the police department as much as possible, saying the seventy officers on the force were woefully overworked, and it was the civic duty of all citizens to look out for robbers, thieves, burglars, pickpockets and other riffraff. “I wish every resident of Akron would look upon himself as a special officer and report any unlawful acts which come to his attention,” Morgan said. “It isn’t necessary for a man to be a regular policeman or even a deputy in order to report misdemeanors and assist in bringing criminals to justice.” Only then would the crime wave ebb, Morgan maintained.

Detective Harry Welch, a police veteran of twenty years, was convinced that Akron’s fine, upstanding residents weren’t suddenly turning criminal. More than likely, it was the newcomers who were responsible for most of the recent problems, he said. “I have watched the town grow, and have studied its criminal element,” he said. “Akron entertains more degenerate transients than any other city in northern Ohio, not excepting Cleveland. It’s the town that’s growing, not the criminal element.”

Welch was convinced of one other thing: It wasn’t a crime wave. “It’s here to stay,” he said. “Just as it is in every large city.”

Mayor William J. Laub issued a proclamation on April 3, 1917, that no foreign-born resident “need fear any invasion of his personal or property rights as long as he goes peaceably about his business and conducts himself in a law-abiding manner.” He concluded, “I urgently request that all our people refrain from public discussion which might arouse personal feeling, and that they maintain a calm and peaceful attitude toward everyone, without regard to their nationality. A very large group of responsible Akron citizens have pledged me their support in maintaining law and order and in guaranteeing to all foreign-born citizens their full rights under our government.”

Three days later, the United States entered World War I. As nearly nine thousand Akron men marched off to battle, women and foreign-born laborers picked up the slack in local factories. Rubber companies welcomed the arrival of so-called aliens as long as they were willing to work hard and follow company rules.

Akron war plants kicked into overdrive, producing military tires, gas masks, boots, gloves, balloons, blimps, hoses, hospital supplies and other rubber products for the Allied effort. New Jersey journalist Edward Mott Woolley (1867–1947) marveled at the boomtown chaos in a July 1917 McClure’s Magazine article titled “Akron: Standing Room Only!”

In Akron there is no quitting time at the rubber factories except at twelve o’clock Saturday night, but every eight hours these vast establishments turn themselves inside out. I stood one afternoon and watched the first shift come out at a plant that employs twenty-one thousand people, and when the flood broke, it was a tidal wave of humanity. It swamped that part of Akron. From sidewalk to sidewalk it rolled down the street, and up it, and swept through every channel and rivulet. Things are doing in Akron. There is standing room only. This is scarcely a jest. There are thousands of beds that are working in shifts like factories. The man who oversleeps is dragged from under the covers by the roomer who has the next ticket.

Don’t get stuck! A plant worker mailed this comical, police-related postcard from Akron to a cousin in West Virginia in 1913. “You ought to come out and git you a job,” he wrote. “There are lots of work.” Author’s collection.

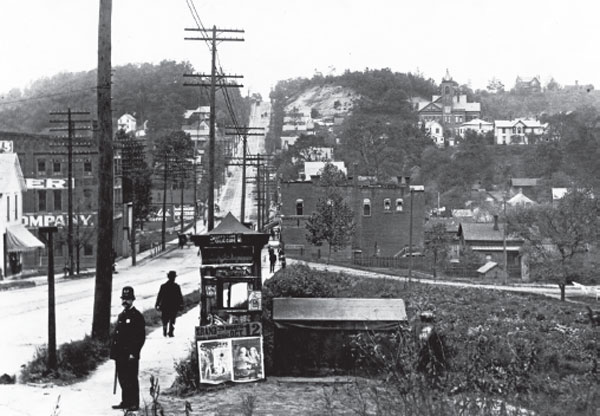

Patrolman Frank McAllister walks the beat on North Howard Street in about 1900, with North Hill looming behind him. Courtesy of Summit County Historical Society.

Dr. Charles T. Nesbitt, who took over as Akron health commissioner in December 1917, cautioned that darker days were ahead. “When great prosperity comes to a city followed by a great influx of population, there nearly always follows a wave of crime and disease,” Nesbitt explained. “The moving of people increases the personal contact, and prosperity always makes a city more attractive to criminals. There is more profit in crime and less chance of detection.”

Akron lost more than three hundred troops in World War I, but the death toll at home was even greater. The arrival of Spanish influenza sickened more than five thousand Akron residents, killing at least six hundred people and turning hospital wards into morgues. Another three hundred died of pneumonia.

Amid the chaos, the criminal element kicked into overdrive. Distracted by war and disease, the gray, grimy city was vulnerable to attack from within. Nothing could prepare Akron for the horrors to come. The melting pot was bubbling over. Stretched to the limit, the Rubber City was about to snap.