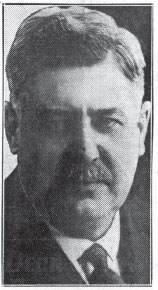

Furnace Street gangster Rosario Borgia, a native of Calabria, Italy, wears a hat and a fur-lined coat in this 1918 police photo. Courtesy of Akron Police Museum.

While Hollywood villains flickered on the silent screens of Akron movie theaters, a real-life menace walked the streets. Rosario Borgia held the town in his powerful fist and tried to crack it like a walnut. Akron was the “City of Opportunity,” and Borgia seldom missed an opportunity.

The twenty-four-year-old Italian immigrant ran the rackets with a ruthless band of gangsters whose illicit operations included gambling, prostitution, robbery, safecracking, extortion and murder. If other hoodlums tried to horn in on business, they disappeared. Akron newspapers published articles about unidentified men whose slashed, bludgeoned, bullet-riddled bodies were fished out of rivers or dug out of shallow graves.

Borgia had so many aliases that no one could keep them straight: Russell Berg, Russell Burch, Mike Burga, Joe Filastocco, Joe Philostopo, Pippino Napolitano, Joe Neapolitan, Rosario Borge, Rosario Borgi and Rosario Borgio. It’s possible that none of those was his real name, although he listed his parents as Giovanni and Maria Borgi on at least one legal document.

He was born in 1893 in the tiny village of Sant’Agata del Bianco, in Cosenza, Calabria, in southern Italy, and immigrated to the United States in 1910, arriving at New York’s Ellis Island aboard the ocean liner Duca d’Aosta and settling in Akron by 1915. Borgia pulled his first thefts as a little boy and was a hardened criminal by adolescence. He may already have been a killer, too. A tale whispered in Akron speakeasies was that Borgia fled Italy because he had murdered his uncle, a police officer who threw him in jail for stealing. Whether true or apocryphal, the story added to Borgia’s menace in America—stay away from that guy; he’ll kill anyone who crosses him, even relatives.

Furnace Street gangster Rosario Borgia, a native of Calabria, Italy, wears a hat and a fur-lined coat in this 1918 police photo. Courtesy of Akron Police Museum.

Borgia was a large man, solidly built, with a lightning temper and intimidating presence. He fought briefly as a professional wrestler before giving up the sport and pursuing other interests, namely women. The Furnace Street red-light district beckoned many Akron newcomers, and Borgia was no different. “White slavery” was a lucrative business, and Borgia wanted a piece of the action.

Reverend Charles Reign Scoville, an Indiana evangelist and Hiram College graduate, warned Akron residents about the dangers of prostitution (and men like Borgia) during fiery sermons at a one-month tabernacle on Cherry Street in 1915. The preacher said that young women risked going astray through coquettish behavior that attracted evil-minded fiends. “Flirtation is next door to damnation, and the girl who sits in public rolling her eyes to see who’s looking at her is flirting as hard as she can,” Scoville said. Speaking against disorderly houses, Scoville told an Akron crowd:

We must wipe out segregated districts and secure law enforcement. No big city has any more excuse for having a tenderloin section than a small country village. Not as much. Most inmates of these houses can say the Lord’s Prayer as well as you or I, and that makes me sick at heart. It shows that they were under the influence and teaching of good parents and a Sunday school some time in their lives. They have actually been stolen and there ought to be a life sentence for any man who steals a pure girl.

Borgia’s first known arrest in the Midwest was on July 7, 1915, on a charge of taking an Ohio girl to Detroit for “immoral purposes.” Six months later, he married Filomena Matteo, twenty-five, an Italian immigrant, before Justice of the Peace Charles W. Dickerson on December 22 in Summit County. On their marriage license application, they listed their occupations as “restaurant owner” and “waitress.”

Streetcar tracks run up the middle of North Howard Street in 1919. Looking north, this view is close to the site where Rosario Borgia operated his so-called restaurant. Author’s collection.

The couple opened a “soft-drink establishment” in their home at 93 North Howard Street, not far from Furnace Street, and brought in young women to separate rubber workers from their cash. Filomena, who could not read or write English, dutifully turned over the money to her husband. Beat cops referred to Borgia’s wife as “Dago Rose,” an Italian slur, and suspected that she was serving more than soft drinks at the business.

Borgia was livid when police conducted a Saturday night raid on the brothel on February 12, 1916. Patrolmen Will McDonnell and George Werne charged Borgia with keeping a questionable business, and they charged his newlywed wife and two other women with inhabiting it. They all were freed on $100 bail.

Perturbed but undeterred, Borgia relocated the “restaurant” to Barberton’s Mulberry Street, where his wife continued to supervise the “waitresses.” Borgia, hardly a paragon of virtue, had the audacity to file for divorce in June 1917, alleging that his wife was “guilty of adultery several times.” The case was dismissed when the couple reconciled.

Ostensibly, Borgia was a barber by trade and worked at a shop on Washington Street, but illicit activities were far more profitable. He diversified his criminal portfolio, surrounding himself with a band of young, like-minded Sicilians who excelled in breaking the law. Money, women, power—they could have it all if they followed Borgia’s lead. The gang liked to hang out at Joe Congena’s pool hall at 121 Furnace Street, where the men occasionally retreated to a back room to make big plans behind closed doors.

The sledgehammered safe at the Acme store on North Hill? That was the work of the Furnace Street gang. The nightclub with the slot machines, punch boards and dice games? That cash went straight to the Furnace Street gang. The floating body in the Cuyahoga River? That guy knew too much and talked too much, so the Furnace Street gang had to silence him.

Detective Harry Welch discovered that Furnace Street residents and business owners were too frightened to talk about gang activity in the neighborhood. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

Detective Harry Welch couldn’t find any Furnace Street residents or business owners willing to talk to officers about the escalating crime wave in the neighborhood. The locals feared for their lives and didn’t want to risk being labeled as squealers. Even when promised police protection, potential witnesses clammed up.

“Victims of the plundering gang continued to shake their heads slowly and refused to identify anyone,” true-crime reporter Will H. Murray wrote decades later. “One shopkeeper showed Welch the gruesome drawing of a skull which he had found on his doorstep the day after he had been held up. ‘The sign of the Black Hand!’ he shivered. ‘To speak is to die.’”

At least five unsolved murders were attributed to Borgia, but he was never convicted of any of them. Nobody wanted to be added to the list. “Rosario Borgia of Barberton is the ringleader of this band of Italian toughs,” theorized George Martino, an Italian American private detective from Akron. “He’s the typical Black Hand captain. He toils not, neither does he spin, and yet he’s always well-dressed and has plenty of money.”

The flashy gang wore ill-gotten wealth on its sleeve, parading around in three-piece suits, silk shirts, flowery ties, wide-brimmed hats and polished shoes. Coiffed, dapper and clean shaven, Borgia led the way with roguishly good looks—an oval face, olive skin, black hair, dark eyes, prominent nose, full lips, jug ears, muscular shoulders and, truth be told, not much of a neck.

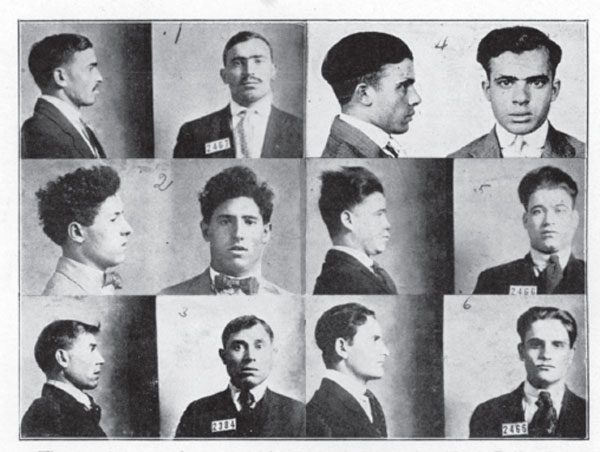

The Akron Police Department takes mug shots of the Furnace Street gang in 1918. Clockwise from top left: Pasquale Biondo, Frank Mazzano, Lorenzo Biondo, Anthony Manfriedo, Paul Chiavaro and Rosario Borgia. Courtesy of Akron Police Museum.

More than a dozen members belonged to Borgia’s crew, but he trusted some more than others. There was Lorenzo Biondo, nineteen, alias James Palmieri, alias Jimmy the Bulldog, a square-jawed bruiser and two-fisted enforcer who always did what the boss ordered as long as the money kept rolling in; Pasquale Biondo, twenty-one, alias Bolo Mazza, alias Patsy Brando, a petulant hooligan, slight of build, with receding hair, a unibrow and wispy mustache and who, despite the surname, angrily insisted he wasn’t related to Lorenzo; Paul Chiavaro, twenty-four, alias Paulo Chivoro, a nebbish sadist who used dum-dum bullets to inflict more damage and coated them with oil of garlic to make the flesh blister; and Anthony Manfriedo, twenty-one, alias Tony Monfredo, a hard-luck underling who refused to kill a friend despite Borgia’s orders, so gang members shot him through the hand, stabbed him in the stomach, robbed him of forty dollars and threw him over a cliff into the Gorge—only for him to crawl out, beg for forgiveness and rejoin the group.

Last but not least was the runt of the litter, Frank Mazzano, eighteen, alias Joe Pelo, alias Nicol Matolli, a five-foot-five thug who was as vicious as he was vain. The Sicilian arrived at Ellis Island in 1914, lived for a year in New York and then settled in Akron about 1915. An elevator operator at Goodrich, Mazzano quit his blue-collar job after getting a haircut from Borgia, who persuaded the teen to come work for him for ten dollars a week. Rosario had an impressionable protégé who could be groomed into a right-hand man.

With exaggerated features, Mazzano’s face looked like it was sculpted from clay. He had large brown eyes, bushy eyebrows, puffy lips and a jet-black pompadour that he carefully combed. In a coat pocket, Mazzano carried a small mirror that he pulled out frequently to survey his looks and groom as needed. Sullen one moment and cracking jokes the next, Mazzano was a typical, rebellious, girl-crazy teenager who just happened to have psychopathic tendencies.

With Mazzano in his thrall, Borgia sent the kid to Mansfield in April 1917 to stalk Carlo Bocaro, age twenty-four, a rival gangster and white slaver from Calabria. Borgia paid for Mazzano’s train fare and gave him money to buy a gun. “Rosario told me to kill him,” Mazzano explained later. “He knew him. They came from the same town in the old country. Rosario said he was a bad man and to shoot him.”

Shortly before midnight on April 14, Mazzano ambushed Bocaro at Sixth and Diamond Streets in Mansfield, shooting him twice in the head and twice in the legs. Unbelievably, Bocaro survived the attack, and Mazzano later joked that he must be a terrible shot. Borgia sent hit man Frank Valona to finish the job, and Bocaro died in a fusillade of bullets on November 15, suffering three more gunshot wounds at close range. Valona was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. Mazzano pleaded guilty to assault and battery and was freed on bond after “out-of-town Italians” fronted the necessary $500.

Patrolmen Ed Costigan, Will McDonnell and other Akron officers knew that Borgia was up to no good, so they made life difficult for him. Vice raids and frequent harassment put a dent in the kingpin’s business. Because Borgia had once been fined $100 for carrying a concealed weapon, Costigan made it a habit of frisking him whenever he saw him.

“The Borgia gang didn’t like Costigan and me,” McDonnell recalled. “Every chance we’d get, we would search them and come up with a knife or a gun. Then they’d be fined. It became pretty annoying to them.…Then one morning we noticed three strangers walking up and down the street, giving Costigan and me the eye. They made three trips up and down. We didn’t think too much about it at the time.”

Borgia greeted officers with feigned affection when he saw them, but deep inside he seethed with anger. “I hate them! I hate them!” he told his gang, a fixation that may have begun with his uncle. Borgia was particularly obsessed with Costigan, the “Red Policeman.”

In late 1917, he hatched a plot to teach the meddling cops a lesson by systematically ambushing them on the streets and putting a bounty on their heads. If necessary, the gang could stage holdups and attack the cops who responded to the calls. Patrolman Norris was the first to die. Costigan and Joseph Hunt were next.

In his usual threatening manner, Borgia ordered three of his men to take care of Costigan—or else. He handed guns to Pasquale and Lorenzo Biondo, pointed to the officers on Furnace Street and told Anthony Manfriedo to serve as lookout on January 10, 1918. “Rosario told me I would be paid $150 for killing ‘Red.’ This was the same night, a half-hour before the murder,” Pasquale Biondo later testified. Borgia said he was tired of being searched and wanted Costigan dead. Then Borgia gave the Biondo men an ultimatum: “You kill him or I’ll kill you.”

The men quietly followed Costigan and Hunt up the High Street hill while Manfriedo stood watch in the gathering darkness. Blam blam blam blam blam!

Pasquale blasted Costigan, while Lorenzo gunned down Hunt. The gangsters ran back toward Furnace Street, dodging gunfire from the mortally wounded Hunt, and hid at an undisclosed location for several days as police interrogated foreigners across the city.

After reading about the slayings in the newspaper, Borgia secretly arranged to meet the killers in Frank Mazzano’s cellar on Cross Street. “You did good work,” he told them. Taking out a wad of cash, he gave $100 apiece to the Biondos and $50 to Manfriedo. Pasquale didn’t know until later that he was shorted $50 of the promised $150. “I didn’t count the money then, but I counted it after I left the house,” he said.

Summit County commissioners offered $3,000 for information leading to the arrest of the murderers whose brazen crimes had made national headlines. It was a tense, frightening time to live in Akron. Killers were on the loose, and no one knew when they might strike again.

When officers canvassed Furnace Street and Howard Street and quizzed Borgia about the shooting of Costigan and Hunt, he denied any knowledge. “I was miles away,” he said. “They were always picking on me. Now you start. Why don’t you lay off? I don’t know a thing about it.”