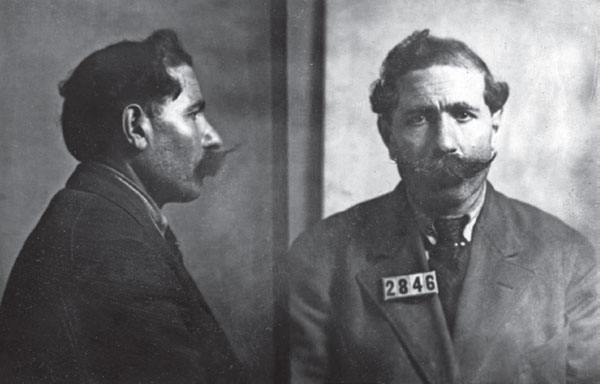

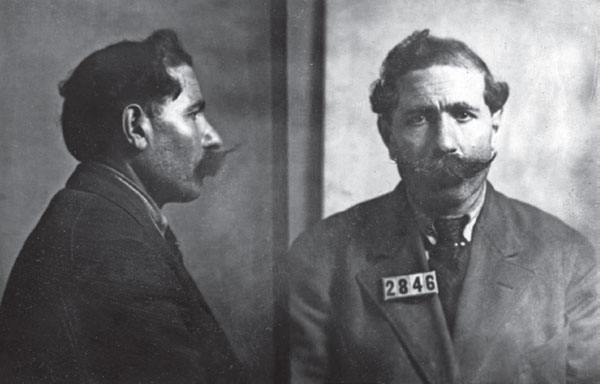

Giacamo Ripellino, better known as Frank Bellini, was the Akron nemesis of Rosario Borgia. Frank Bellini mug shots. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

At the request of Akron police, Italian American private detective George Martino began snooping around Furnace Street for any potential leads in the slayings of the three patrolmen. Martino had plenty of dealings with unsavory characters as the former owner of a Case Avenue saloon. He knew how to talk the talk and walk the walk. Plus, he was morally ambiguous.

He once was sentenced to a month in the county jail for contempt of court after shielding the identity of a larceny suspect. Another time, he was named as a suspect in a $100 shortage from the Italian Foreign Exchange Bank, where he served as secretary, but the case was settled out of court. He also was implicated in a Cleveland scheme to pocket $100 in bond money that was intended for a fugitive.

Word soon got back to the Furnace Street gang that an outsider was asking questions in the neighborhood. If Martino kept sticking his nose in other people’s business, he just might lose it.

The private investigator caught wind in early March 1918 that Rosario Borgia’s boys might try to bump him off. His pulse quickened one evening when he realized that some tough-looking hoodlums were following him in downtown Akron. As Martino later explained:

I had started east on Mill Street and the gang, starting from the Hotel Buchtel, trailed me. When I reached Broadway, I speeded up and instead of going over the viaduct, I dodged under and hid myself near the Pennsylvania freight house. I had my gun and was in a position where I could have dropped them one at a time. Evidently, the bunch thought I had crossed the viaduct, because they passed overhead and turned north on Prospect Street.

Martino escaped that night, but others wouldn’t be as lucky. Two months after assassinating the cops on High Street and one week after giving Martino a scare, Borgia was ready to kill again. This time his target was Sicilian businessman Giacomo Ripellino, age forty, better known as Frank Bellini, who owned a rival “soft-drink parlor” and cigar shop on North Howard Street. Bellini, whose distinguishing characteristic was a massive, sculpted black mustache, had met Borgia three years earlier and feuded with him for nearly as long. Bellini was quiet, calm and polite; Borgia was loud, boisterous and emotional. Each accused the other of tipping off authorities to their illegal enterprises, causing vice raids that put a crimp in business.

Although the men hadn’t been on speaking terms for a year, Borgia signed a $10,000 contract in March 1918 to buy a home at 1014 Canal Street that Bellini had operated as a “questionable resort.” Borgia invited Bellini to discuss a trade agreement on Monday, March 11, at the Furnace Street poolroom, purportedly to resolve their differences, but Bellini suspected that the afternoon meeting was a trap and declined to go. An aggravated Borgia sent Frank Mazzano to remind Bellini of the appointment, but the Sicilian again failed to show up.

Giacamo Ripellino, better known as Frank Bellini, was the Akron nemesis of Rosario Borgia. Frank Bellini mug shots. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

With each passing hour, Borgia grew angrier. He drank wine, cracked walnuts and cursed Bellini while waiting in the smoke-filled billiard hall with Mazzano, Paul Chiavaro and other associates, including Salvatore Bambolo, Calcedonio Ferraro and Carmelo Pezzino. Borgia retreated to the back room with a few henchmen for a private meeting that lasted more than a half hour. “Borgia stopped me when I attempted to enter, told me to keep outside and shut the door,” Pezzino later recalled.

Outfoxed by his nemesis, Borgia gave up on Bellini around 11:30 p.m. “Let him be tonight,” he muttered. “We get him another time.” Bellini’s intuition was correct. If he had gone to the pool hall, he surely would have vanished like so many of Borgia’s other enemies.

Borgia led his men on a night parade through downtown Akron. It was cloudy and mild but windy as they walked south on Main Street, turned east on Exchange Street and stopped at Washington Street (now Wolf Ledges Parkway), where Bambolo, Ferraro and Pezzino said good night and went home. Borgia, Mazzano and Chiavaro turned back around. All three had loaded revolvers and weren’t ready to call it a night.

Walking shoulder to shoulder on the sidewalk just before 1:00 a.m., the Italians spied a dark figure drawing closer under the streetlights. George Fink, a Goodrich worker, was walking home from a friend’s house when he ran into the intimidating group at the Erie Railroad tracks. The well-dressed men, wearing overcoats and fedoras, refused to make room on the sidewalk and then roughly jostled him when he tried to pass. Thinking he was about to be robbed, Fink shoved his way past the ruffians and ran.

Patrolman Gethin Richards was walking the beat about a block away near Grant Street when an agitated Fink, an old acquaintance, stopped him to complain that three men had just tried to hold him up. “Who are they?” Richards demanded. Fink pointed to the men traveling west on Exchange and replied, “There they go.” Clutching a nightstick, the cop hurried off to pursue the Italians, while Fink tried to keep up.

Richards, thirty-seven, a ten-year veteran of the force, was a tall, brawny cop who was well known and well liked in his hometown. A son of Welsh immigrants, he had lived his whole life in Akron, and like everyone else, he was taken aback by the city’s rapid growth. He quit his security job at the Werner publishing company in 1907 to become a police officer and made a run for Summit County sheriff in 1914 on the Progressive Party ticket. As he noted in campaign advertisements:

I do not think those who know me will question, but if elected I could and would fill the office acceptably to the people. However, this section has grown rapidly and while I used to know practically all of our people, that is no longer true. To those I do not know and who do not know me, I want to say this: I am not a politician and if I am nominated and elected, there will be no politics connected with the office of sheriff of Summit County. This important office I shall regard as a public trust and its duties shall be executed as the law directs without favor or malice to friend or foe, and at the smallest possible expense to the people.

Patrolman Gethin Richards, a lifetime resident of Akron, was a ten-year veteran who once ran for Summit County sheriff. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

One of more than a dozen candidates, Richards managed only seventy-four votes in the primary—at least two thousand fewer ballots than Republican hopeful Jim Corey, who went on to win the general election. The campaign over, Richards settled back into his beat.

Richards was an efficient, orderly lawman who didn’t put up with any shenanigans. When he caught Alfred Minns mouthing off to pedestrians, the patrolman boxed the young man’s ears and charged him with disorderly conduct. When Gus Shue ordered a thirty-five-cent meal at the Gridiron restaurant without a penny in his pocket, Richards carried him by the collar to police court. When James Porter tried to steal several coils of copper wire from a Bell Telephone truck, Richards caught him in the act and threw him in the slammer. When Fred Hayward refused to buzz off after being accused of loitering on Main Street, Richards dragged him away on the sidewalk.

A family tragedy soon turned the patrolman’s orderly world upside down. His thirty-one-year-old wife, Frieda Richards, died unexpectedly in April 1916 after falling into a diabetic coma, leaving the stunned cop with two young daughters to raise. His German-born in-laws, Fred and Marie Raeder, lived in the Richards home at 600 Grant Street and looked after the girls—both pupils at Leggett Elementary School—while their father worked nights. The daughters were home asleep at 1:00 a.m. on March 12 when Richards prepared to arrest some bad guys.

If Borgia, Mazzano and Chiavaro knew they were being followed, they didn’t show it. At High and Exchange, they ambled past German-American Music Hall, whose name recently had been shortened to Music Hall because of anti-German sentiment, and turned north on Main Street. Stealthily, Patrolman Richards cut the corner to head them off, racing north on Maiden Lane and west on Kaiser Alley, while his buddy Fink walked quickly along Exchange. Richards caught up to the three Italians in front of the John Gross hardware store at 323 South Main Street.

“Hands up!” Richards ordered as the men wheeled to face him. Wielding his nightstick, the officer grabbed Borgia and began to search him for weapons. For a moment, Mazzano and Chiavaro stood frozen, unsure what to do, but the boss saw an opportunity and took it. As Richards patted down Borgia, the former pro wrestler reportedly grabbed the six-foot, two-hundred-pound cop’s arm and twisted it behind his back.

“Shoot him!” Borgia shouted in Italian. “If he finds the guns on us, we will all go to the electric chair.”

As Richards struggled to break free, Mazzano pulled a revolver and fired twice, missing both times and striking windows of a nearby storefront. “What’s the matter with you?” Borgia hissed. “Are you trying to shoot me?”

Serving as lookout, Chiavaro yelled, “No one is looking.” Mazzano steadied the Colt .38 in both hands and shot the officer once in the stomach and twice in the chest. Richards stumbled a few feet and collapsed on the brick street. George Fink turned the corner just in time to see the flashes of gunfire and dived for cover in the doorway of Joseph Ivory’s foreign exchange bank. Lights blinked on in one dark apartment after another as the noisy barrage awakened neighbors. Blinds opened and curtains parted. A woman leaned out a window and screamed for help after seeing the officer writhing in the street.

A 1948 police magazine on display at the Akron Police Museum depicts three gangsters fleeing after the 1918 shooting of Patrolman Gethin Richards. The falling hat became a key bit of evidence. Courtesy of Akron Police Museum.

The Akron Police Department shows off its new Packard squad car in front of the Summit County Courthouse in late 1917. In the front seat are Captain Robert Guillet and Fred Work. In the back seat are Patrolmen Paul Kraus, A.O. Nelson and John Mueller. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

As the three gangsters ran away—Borgia fled north while Mazzano and Chiavaro scattered west—they tossed their guns aside, and Mazzano’s green felt hat flew off his head. Fingerprint identification was still in its infancy in American justice, so the criminals’ only concerns were getting rid of the evidence and not getting apprehended.

Fink scrambled over to Richards and grabbed the wounded officer’s revolver with a vague idea of chasing the gangsters. “For God’s sake, Fink, don’t leave me,” Richards pleaded. “I’m going to die.”

Moments later, Officers Howard Pollock and Roy A. Barron screeched to a halt in the Ford squad car while investigating the sound of gunfire on Main Street. As the men loaded Richards into the car, he ordered, “Get me to the hospital as quick as you can. I’m going to die.”