Downtown Akron bustles at night in this 1917 postcard of North Main Street. This view is looking north from the Buchtel Hotel. Author’s collection.

With officers converging on the scene, a desperate Frank Mazzano and Paul Chiavaro ran a zigzag pattern to escape: east on Exchange, north on High Street, east on Buchtel Avenue and south on Broadway. Patrolman Oscar Wunderly gave chase when he saw two shadowy figures dart toward the railroad tracks.

If the gangsters had hoped to leap the rails and flee east toward the University of Akron, a lumbering freight train blocked their path. They had no choice but to run north.

Stumbling in the dark, Mazzano and Chiavaro followed the tracks toward the City Ice & Coal Company off Center Street (known today at University Avenue). They soon discovered that they had more to worry about than Akron police. Detective Henry LeDoux and Patrolman Edgar Bush, officers for the Erie Railroad, had been chatting in a wooden shanty when they heard the Main Street gunfire and went outside to investigate.

Several minutes later, LeDoux noticed two suspicious men approaching. One was wearing a hat, and the other was bareheaded. LeDoux calmly drew his pistol and ordered the strangers to stop. “Don’t shoot!” Mazzano cried out. “Please don’t shoot!”

Winded from the chase, Mazzano and Chiavaro surrendered. LeDoux discovered .38 bullets in Mazzano’s pocket and a loaded revolver that Chiavaro had tossed along the tracks. Wunderly caught up to the group and took custody of the suspects, saying, “OK, they’re our babies now.”

Downtown Akron bustles at night in this 1917 postcard of North Main Street. This view is looking north from the Buchtel Hotel. Author’s collection.

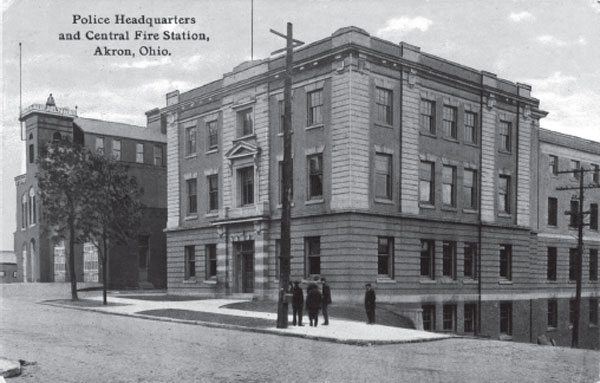

Akron’s old police station is pictured at South High Street and Quarry Street (now Bowery) in this 1911 postcard. Author’s collection.

The Akron officer called for the patrol wagon and loaded the men into it, stopping Mazzano when he tried to use a seat cushion to rub gunpowder residue from his hands. The young, sullen hoodlum later asked to use a washroom at the police station but was rebuffed. He initially denied being the gunman, claiming that “Joe Belo” shot the officer. Technically, that was true because Belo was his alias. Officers found his mangled .38 revolver, apparently run over by a streetcar, in a gutter near the scene of the shooting, and a .32-caliber Colt in the doorway of the Hosfield & Rinker clothing store on South Main.

“I was sitting in the chief’s office talking to Mazzano when they brought in the gun that the car had run over and put in on the chief’s desk,” Italian American private detective George Martino later testified. “I pointed to the gun, which was a Colt .38 police special and said to Mazzano ‘Is this the one you had?’ Mazzano answered ‘yes.’”

Officer Joe Petras transported Mazzano and Chiavaro to Peoples Hospital (known today at Akron General Medical Center) and marched them into the operating room, where Patrolman Gethin Richards was waiting. The wounded officer looked carefully at the two downcast men standing at the foot of his bed.

“That is the fellow who shot me,” Richards said, pointing to Mazzano. “And that other one was with him. There was another one. Still bigger than either of these.”

Ducking in and out of doorways, Rosario Borgia escaped detection as he scurried toward the Buchtel Hotel at South Main and East Mill Street in downtown Akron. It was five long blocks from the scene of the officer’s shooting, but he managed to sneak back to the room he had reserved two nights earlier. Samuel Holbrook, night clerk at the Buchtel, saw Borgia arrive around 1:30 a.m. and go straight to his room but didn’t think anything of it. Borgia often stayed at the hotel on nights when he didn’t feel like going back to his wife in Barberton.

The gangster must have breathed a sigh of relief when he closed the door behind him. Gaining confidence with each tick of the clock, he turned off the lights and climbed into bed. Surely he had gotten away with it. About two hours later, he heard a loud, insistent knock on the door.

“Open up or I’ll break in,” demanded Detective Edward J. McDonnell, the kid brother of Patrolman Will McDonnell. He and Patrolman Verne Cross had checked the front desk around 3:30 a.m. to see if anyone had arrived after 1:00 a.m. The hulking Borgia, the only latecomer, opened the door and feigned ignorance when asked about the shooting. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said.

Detectives Eddie McDonnell and Pasquale “Patsy” Pappano attend the 1931 funeral of Captain Frank B. McGuire at St. Sebastian Church. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

Cool as a cucumber, Borgia identified himself as Russel Berg and insisted that he had dined at a chop suey restaurant around 10:00 p.m. and taken a walk to get some fresh air, but he didn’t know anything about an officer being shot. When the officers escorted the suspect to headquarters for further questioning, Detective Harry Welch casually shredded the man’s alias, noting, “Hello, Rosario. Haven’t seen you recently.”

Steadfastly denying any involvement in the attack on Richards, Borgia was taken to the city jail, where he was reunited with Mazzano and Chiavaro, along with Salvatore Bambolo, who was being held as a material witness. The sleepless men exchanged words in Italian and waited to see what would happen next.

Across town, police woke up the relatives of Gethin Richards and rushed them to Peoples Hospital. Sergeant Marvin Galloway, who spent the predawn hours quizzing the wounded officer about the shooting, was present when the cop’s brother Jack Richards arrived.

Gangster Paul Chiavaro used dum-dum bullets coated with oil of garlic to make the flesh blister. Courtesy of Akron Police Museum.

“They’ve got me at last,” Gethin Richards said. “You’ll look after my two little girls, won’t you, Jack?”

“You bet I will,” the teary-eyed brother replied.

Next, the two bewildered daughters—Marie, age ten, and Violet, age six—were ushered into the room with their grandparents. “He called them to his side and kissed them goodbye,” Galloway later testified.

Richards grew weaker after surgery. By late morning, he drifted in and out of consciousness. No longer able to speak, he answered questions with a nod of his head. Relatives were at his bedside when the thirty-seven-year-old officer died at 12:36 p.m. on Tuesday, March 12. Akron had lost its fourth cop in three months.

Cletus G. Roetzel, twenty-eight, Summit County’s dashing young prosecutor, called for a special grand jury about twenty minutes after Richards died. Recalling the 1900 riot, Chief John Durkin had Sheriff Jim Corey drive Borgia, Mazzano and Chiavaro to the Cuyahoga County Jail in Cleveland for their protection.

More than seven hundred people, including most of the police force, attended the funeral on Friday, March 14, which began at the family’s home on Grant Street and concluded with Masonic rites at Mount Peace Cemetery, where Richards was buried next to his wife, Frieda, a stone’s throw from the fresh grave of Patrolman Costigan. Reverend E.W. Simon of Trinity Lutheran Church officiated. A shield of carnations forming “28,” the officer’s badge number, rested on the casket.

Pedestrians and motorists halted as the hearse passed through downtown Akron. A military band led the procession, followed by sixty officers—including pallbearers Fred Vierick, Edward Hieber, Andrew Croghan, John Duffy, Verne Cross and Marvin Galloway—and then, finally, a parade of automobiles.

“There were tears in the eyes of the onlookers, and a murmured word of sympathy,” the Beacon Journal reported. “Marie, the elder of the two children, wept her eyes red; only six-year-old Violet looked wide-eyed and wondering. In a moment of intense grief, the aged mother-in-law was overheard to murmur, ‘Has God forsaken me?’”

Later that afternoon, a grand jury indicted Borgia, Mazzano and Chiavaro on charges of first-degree murder and carrying concealed weapons. At least a dozen Akron lawyers refused to act as the defense counsel for the suspects, who returned from Cleveland and were arraigned Monday, March 18, before Summit County Common Pleas judge Charles C. Benner. A.C. Bachtel, clerk of courts, read the indictments with the aid of an Italian translator, and all three defendants pleaded not guilty.

Unbeknownst to Borgia and Mazzano, though, Chiavaro had ratted them out in the police interrogation room. After pleading not guilty, he signed a confession in Prosecutor Roetzel’s office with a court stenographer and translator present but no defense lawyer.

“Who shot Richards?” Roetzel asked.

“Mazzano,” Chiavaro said.

“Who else was present?”

“Borgia and myself.”

“Now, in your own words, tell us what happened.”

In a matter-of-fact matter, Chiavaro described the officer’s murder to Roetzel:

As we turned north on Main Street, after rounding the corner on Exchange Street, Richards ran out of the alley. Borgia was in the lead. Richards stopped us. Next to Borgia was Mazzano. I was in the rear. Richards started to search Borgia. His hands were in the air. Mazzano was about 5 feet in the rear. Suddenly, Borgia grabbed Richards’ arms and stepped down. Mazzano had drawn his gun and as Borgia ducked, Mazzano opened fire. As Richards was hit, Borgia tore himself away and ran north on Main Street. Mazzano fired five shots and we ran through the alley and back toward the railroad yards.

The county prosecutor had heard enough. In the event of a conviction, he would insist on the electric chair. “It must be either the death penalty or nothing else,” Roetzel told a reporter.

But the three men wouldn’t be tried alone. Patrolman Pasquale “Patsy” Pappano, age twenty-five, an Italian-born cop who had been on the force for only six months, was working the case.

The six-foot, barrel-chested rookie was a native of Roseto Valfortore in Puglia, Italy, who had immigrated to the United States at age eleven. Chief Durkin needed an officer who understood the language and the customs. “The others couldn’t speak Italian and the chief said, ‘We’re having so much trouble with these Borgia boys and others, I want that Pappano boy with me,” Pappano later recalled.

A trusted cop, Pappano cultivated informants who told him that Furnace Street gang members Lorenzo Biondo and Anthony Manfriedo were hiding out in New York City, waiting for the heat to die down in Akron. He took the news to Detective Harry Welch, who contacted Michael Fiaschetti, an Italian-born detective sergeant in the New York Police Department.

Fiaschetti was commander of the “Italian Squad,” a five-man unit of Italian American cops whose mission was to investigate organized crime and bring gangsters to justice. Fiaschetti operated a network of stool pigeons to keep tabs on underworld figures. If those Akron boys were in New York, he could find out.

Manfriedo had a noticeable bullet wound, a memento from when the gang shot, stabbed and threw him over a cliff for refusing to bump off a rival. “Look for the man with a hole in his hand,” Welch wrote.