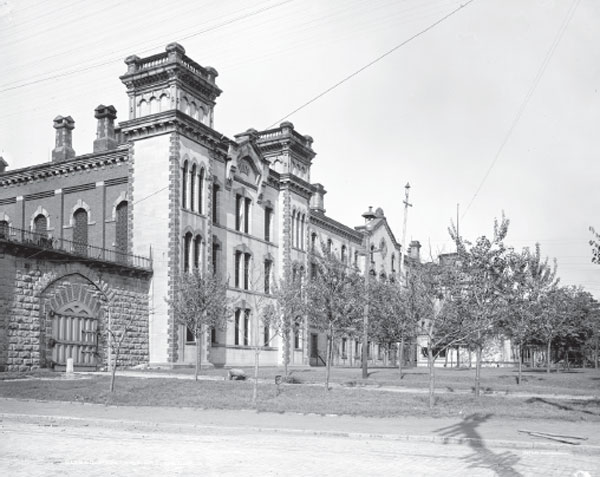

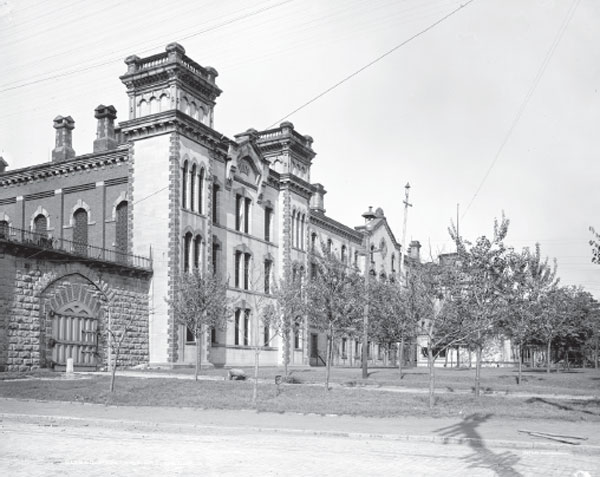

Following the murder trials in Akron, the Furnace Street gang was sentenced to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Rosario Borgia, Akron underworld czar, sputtered in disbelief after the verdict. “That was a hell of a jury!” he cried while being led back to his cell. “And that lawyer didn’t try to defend me.” Thinking it over, he muttered, “I suppose those Italians, those Sicilians, are satisfied now. They got me where they want me.” Borgia’s wife, Filomena, who hadn’t visited the jail in ten days, sent a fruit basket to her husband on the day after he was convicted. “To hell with this stuff,” he told a deputy. “Tell my wife to come to the jail to see me.” When she arrived, the couple quarreled. “Take me out of here immediately,” she told a jailer.

After a day to calm down, Borgia began to regain his swagger. “Why should I be afraid if I have lost the case?” he told a jailer. “I’ll get a new trial. I got lots of money and I can get more.” His lawyers filed a motion for a new trial, complaining, among other things, that the case should have been heard in a different county and that jurors should have been sequestered. Judge Ervin D. Fritch swatted away the motion.

Only a handful of spectators attended the hearing on Saturday, May 25, 1918, where Fritch sentenced Borgia to die in the electric chair. Asked if he wanted to make a statement for the record, Borgia merely sulked, “I have nothing to say.” He returned to his cell to await the trip to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus.

Later that day, Akron’s Italians celebrated the third anniversary of their native country’s entry into the Great War. Businesses closed early so everyone could attend a grand parade featuring musicians, floats, banners and a procession of two thousand Italian Americans. They marched from North Howard Street to Exchange Street and back, passing the county jail, where Borgia no doubt was still muttering.

Following the murder trials in Akron, the Furnace Street gang was sentenced to the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

With Borgia’s conviction, public interest waned in the Furnace Street gang, but there were still four more trials scheduled that summer. Next up for Judge Fritch was Pasquale Biondo, charged in the January 10 murder of Patrolman Edward Costigan. Although Biondo had signed a confession, he claimed he only did it because New York detective Michael Fiaschetti had tricked him into believing he’d get a lighter sentence.

The court appointed Seney A. Decker and Carl Myers to serve as Biondo’s defense. “While I do not care for the task which has been assigned to me and did not solicit it, as an officer of the court, I feel it my duty to do the utmost for the defendant,” Decker announced. “He is entitled to a fair and impartial trial under the rules of the evidence.” However, in his opening statement June 13, Decker admitted that he and Myers were not familiar with the case but hoped to prove that the crime was not “a free act of a free agent.”

Prosecutor Cletus Roetzel introduced Biondo’s confession of killing the “Red Policeman” for $150 under Borgia’s command. “You kill him or I’ll kill you,” Biondo quoted Borgia as saying. The state questioned dozens of witnesses, but Biondo’s own words probably were sufficient for a conviction during the climate of the time. As Assistant Prosecutor Charles P. Kennedy told jurors in his closing argument:

If you let a man who has committed a crime like this one go unpunished, if you give a recommendation of mercy to a man who for $150 crept up silently behind a man whose very name he did not know and shot him down like a dog, a man who had done him no harm, then I say to you that you will have the thieves, thugs and murderers flocking into Akron as a fertile field for their crimes.

The trial wrapped up in five days, and the jury deliberated only seventeen minutes before reaching a verdict. Biondo was found guilty of murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair. “I don’t care,” he told a jailer, adding facetiously, “I should worry.” Oh, but he did care. On July 4, the convicted killer tried to escape from the county jail.

He and three other inmates overpowered Deputy John W. McCaslin in the shower room, and Biondo seized the officer’s gun and shot William F. Lowe, a trusty, in the abdomen when he tried to intervene. After a frantic search, Biondo couldn’t find the keys, though, and surrendered when Deputy Scott Ingerton pointed a gun at him and ordered him to surrender. Fortunately, the bullet missed Lowe’s stomach and liver, and he survived the shooting. Biondo was thrown back into his cell to await the trip to Columbus.

Paul Chiavaro was the next gang member to be tried before Judge Fritch. Detective Harry Welch always suspected that Chiavaro was the killer of Guy Norris, the first victim of the gangland war, but he could never pin it on him. Instead, Chiavaro was charged in the March murder of Gethin Richards, even though the gangster had only served as a lookout.

In the opening statement on June 28, defense attorney Stephen C. Miller contended that Chiavaro was only a spectator that deadly night and didn’t even belong to the gang. Miller audaciously claimed that his client had merely gone for a late-night stroll with Borgia and the others after meeting them at the Furnace Street pool hall owned by Joe Congena.

Prosecutor Roetzel painted a grimmer picture, noting that Chiavaro was a hardboiled henchman who liked to use dum-dum bullets to inflict more damage on his victims, and he coated the bullets with oil of garlic to deaden the nerves and blister the skin. In other words, the guy wasn’t exactly a choirboy.

Prison guards keep close watch on the barred cells of death row inmates at the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

Convicted killers Borgia and Frank Mazzano were called back to the stand to testify, and they largely repeated their statements from the earlier trials. Chiavaro, who only spoke broken English, took the stand on July 3 and got confused as Roetzel read back the gangster’s confession from earlier that year. When asked if those were his words, Chiavaro said, “I don’t know if I said it or not.” When Roetzel noted that Chiavaro had denied any involvement in the shooting after being arrested, the gangster said, “I was excited. I was excited. My head was mixed. I didn’t know what I was saying.”

In closing arguments, prosecutors told jurors that even though Chiavaro served as a lookout, he was just as guilty of murder as Mazzano, the triggerman, and Borgia, the man who ordered the killing, because he had aided and abetted the death of Patrolman Richards. Jurors began deliberations at 4:30 p.m. on Friday afternoon and returned a verdict at 11:00 p.m. that night: guilty without recommendation of mercy. Sentenced to death at a July 13 hearing, Chiavaro could only grouse, “I am not to blame.”

After the Chiavaro trial, Prosecutor Cletus Roetzel got ready for military training at Camp Taylor and turned over the reins to assistants Charles P. Kennedy and William A. Spencer. Meanwhile, Judge William J. Ahern took over for Judge Fritch. Perhaps that’s why the outcomes were so different—or maybe it was because of the defense lawyers.

Lorenzo Biondo, alias James Palmieri and Jimmy the Bulldog, went on trial August 7 in the January slaying of Patrolman Joe Hunt. He hired Cleveland attorney Benjamin D. Nicola, age thirty-nine, as his defense lawyer, and it was an inspired choice. Nicola was born in Italy in 1879, immigrated to the United States at age nine and grew up in the Tuscarawas County town of Uhrichsville, where his family operated a general store and butcher shop.

After high school, Nicola studied law at Ohio State University, passed the bar exam in 1904 and put up a shingle in Cleveland, where he became the first Italian American lawyer in the city’s history. Unlike other attorneys for the Furnace Street gang, Nicola understood the Italian culture and spoke the language.

His plan of attack in the Biondo trial was to discredit the confession that his client had given to New York detective Michael Fiaschetti after being captured in Brooklyn. In his opening statement, Nicola reminded jurors to keep their minds open because a man was presumed innocent until proven guilty.

The electric chair awaits the Akron police killers at the Ohio Penitentiary. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

The defense began to hammer away at Fiaschetti, the cosmopolitan cop described by co-counsel Henry Hagelbarger as “the dressy detective,” “the handy Andy” and “the courthouse favorite.”

Anthony Manfriedo, who served as the lookout on the night that Costigan and Hunt were slain, took the stand to back up the defense’s contention that he and Lorenzo Biondo signed confessions because Fiaschetti promised them that they would escape the electric chair if they did. “They don’t want you, they want Borgia,” Manfriedo said the detective told them.

In rebuttal, Kennedy called Fiaschetti to testify about his tactics with Biondo. “All I told him before he made the confession was that Manfriedo had made a true statement and that Mazzano had identified him as the man and that it would be better for him to tell the truth,” he said.

With the war in Europe dominating headlines, Akron residents showed little interest in the Biondo case. The sweltering courtroom didn’t have air conditioning and sat mostly empty as summer temperatures soared to a record-breaking 104 degrees.

In closing, Kennedy told jurors that Biondo was nothing but a coward for shooting Hunt in the back: “And what a price for a human life. A man that he did not know and against whom he had no grievance. A paltry $100, which this man Biondo tries now to tell you was forced upon him by Borgia.”

But Nicola told jurors that Biondo only acted “under the power and fear” of Borgia. If he hadn’t shot the officer, Biondo would have been killed himself, Nicola said. He beseeched the juror for leniency.

The jury began deliberating at 3:45 p.m. on Tuesday, August 14, and wrestled with the case for eighteen hours before going home for the night without a verdict. According to courtroom scuttlebutt, the jury initially voted eleven to one for the death penalty but couldn’t get the twelfth man to agree. H.T. Wallace, a Republican candidate for Ohio representative, served as foreman.

“The jury made an attempt to communicate with Judge Ahern Wednesday morning by a written statement,” the Beacon Journal reported. “Ahern destroyed the statement unread and sent word to the jury by the bailiff that such a procedure was not allowed and for them to make no attempt to communicate with him until they reached a conclusion.”

Deliberations resumed, and rumors circulated of a deadlock before the panel announced it had finally reached a verdict about twenty-four hours after the discussions began.

“Have you reached a conclusion?” Judge Ahern asked the jury.

“We have,” Wallace said.

The jury found Biondo guilty of first-degree murder with a recommendation of mercy. A confused Biondo looked to Nicola for an explanation and was visibly relieved when the attorney explained that the verdict meant life in prison instead of the electric chair. At the sentencing hearing on August 24, Judge Ahern added a clause to the life term. Every February at the Ohio Penitentiary, Biondo would have to spend four days in solitary confinement to remind him of the four days that Patrolman Hunt lingered before dying.

Anthony Manfriedo’s case was resolved in record time. On Friday, August 16, 1918, the confessed lookout and all-around lackey avoided a jury trial by pleading guilty to murder as an accessory and throwing himself on the mercy of the court. Judge Fritch sentenced Manfriedo to life imprisonment on August 20 and sentenced him immediately to the Ohio Penitentiary to be reunited with his old gang.