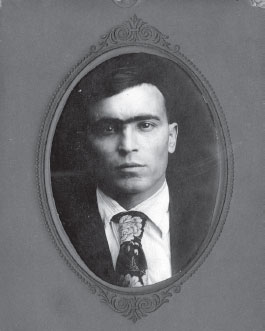

Pasquale Biondo was executed on October 4, 1918, for the murder of Patrolman Ed Costigan. The execution could have been delayed, but the paperwork arrived late in the mail. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection (State Archives Series 1000 AV).

As a matter of course, defense attorneys appealed the sentences of Rosario Borgia, Frank Mazzano, Pasquale Biondo and Paul Chiavaro as they sat on death row in Columbus. Appellate judges began taking up the cases in September 1918 and postponed three of the four executions until early 1919. An unbelievable mistake caught the justice system by surprise.

Biondo’s execution was scheduled for October 4, 1918, at the Ohio Penitentiary. As the date drew closer, court-appointed attorney Seney A. Decker of Barberton worked on the paperwork for a stay of execution. The board of appeals in Cleveland agreed in early September to grant a reprieve, but Decker neglected to prepare an entry in the court journal as required.

Notified of the oversight, Decker had a justice of the peace deliver the proper documents to Cleveland early Tuesday, October 1, but the appellate judges were away at a Liberty Loan event, so a clerk promised to have the judges sign the papers and mail them to Barberton in time to halt the execution.

The twenty-seven-year-old Biondo waited for a call that didn’t arrive. He spent his final hours praying with Reverend Francis Louis Kelly, age sixty-seven, a Roman Catholic prison chaplain, before they walked together to the death chamber. Passing Borgia’s cell, Biondo shouted, “I’ll see you in hell!”

Afterward, Biondo showed no emotion as he marched toward the electric chair. He prayed with the priest and kissed a crucifix before being blindfolded and strapped into the chair. Patrolman Edward Costigan’s killer declined to deliver any last words before the electric current passed through his body shortly after midnight. After thirty seconds, Dr. O.M. Kramer, prison physician, pronounced the gangster dead.

Pasquale Biondo was executed on October 4, 1918, for the murder of Patrolman Ed Costigan. The execution could have been delayed, but the paperwork arrived late in the mail. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection (State Archives Series 1000 AV).

About nine hours later, the letter granting a stay of execution arrived in the mail at Decker’s office in Barberton. As the defense attorney told the Beacon Journal:

It is a very unfortunate state of affairs, but it is simply the result of circumstances over which no one had any control, and while no one knows what the ultimate outcome would have been had we the chance to argue the case again, I regret exceedingly that the execution was not stayed because there were several important questions of law which should have been passed by the court of appeals.

As Judge Charles R. Grant concluded at the appeals court, “It is a regrettable occurrence and should be a lesson to attorneys in such criminal procedures in the future.”

When news broke that the Allies had signed an armistice with Germany to end the Great War in Europe, giddy Akron residents celebrated with a massive parade on November 11, 1918. Hundreds of thousands of residents poured into the streets in a cathartic overflow of joy. Church bells rang, factory whistles blew and motorists honked horns. The war was over! The troops were coming home! The following day, Sheriff Jim Corey escorted Borgia and Mazzano to Akron to attend a quiet appeal of their death sentences. The former friends were handcuffed together and led into the Summit County Courthouse.

Defense attorneys said the men deserved another trial for multiple reasons, including prosecutorial misconduct, the trial judge’s errors and a lack of sufficient evidence. The appellate court refused. “Mazzano’s was a dastardly crime committed in response to the instructions of the padrone,” Judge Grant said. “The case was tried with patience and exceptional ability, and this court finds no error.”

Regarding Borgia’s appeal, Grant stated, “You murdered a man who had never offended you and made his children orphans. You made the mistake in assuming that a practice en vogue in the mountains of Sicily could be followed here.”

Borgia didn’t have time to explain that he was Calabrian, not Sicilian. The men’s execution date was affirmed for February 21, 1919, in Columbus. Partners in crime, they would die on the same night. Borgia and Mazzano were escorted through the tunnel to the county jail. “We only got to die once, so we should worry!” Borgia shrugged to jailer J. Henry Bair. “Goodbye. We may not see you again.”

After the Ohio Supreme Court denied a final appeal on January 21, the Ohio Parole Board refused a commutation and Governor James M. Cox declined to interfere, the gangsters’ fate was sealed. The condemned men were kept in solitary confinement at the death house and weren’t allowed visitors.

“Oh, Rosario, my man, my Rosario!” Filomena Borgia wailed on February 20 outside the gray stone walls of the Ohio Penitentiary. “Oh, what a shame to kill you, my man, my Rosario! Rosario, they are going to kill you, to take you from me in a few minutes. I will kill myself, Rosario, my man!”

Inside the death house, things were proceeding as scheduled. A prison barber shaved a circle on Borgia’s and Mazzano’s heads and shaved their right calves for the placement of the electrodes. The condemned men somehow had rekindled their friendship on death row. Mazzano forgave Borgia for leading him down a criminal path as an impressionable youngster. Borgia tried to overlook the fact that Mazzano had ratted him out in court. If only they had been able to tame their murderous impulses, they could have made a black market fortune as bootleggers during Prohibition, which was ratified into law that same month.

On the eve of the execution, Borgia and Mazzano spent two hours talking with Sheriff Pat Hutchinson, who took office in January, and Akron cops Ed and Will McDonnell. The convicts had ordered a last meal of fried chicken and ice cream, but they barely had a bite.

“The ice cream melted and ran over the dish while we stood there,” Will McDonnell said. “It reminded me of the sand in an hourglass as it indicated how quickly death was approaching for the two men.”

Borgia and Mazzano made a last-hour request for former sheriff Corey to visit them. He was summoned from the death chamber, where he was preparing to witness the executions with W.L. Norris, the father of Guy Norris, the first cop killed in the gangland war.

“Hello, Jim,” Borgia said upon seeing Corey. “Frank wants to make a confession.”

“I don’t want to die with a lie on my lips,” Mazzano told Corey. “When I testified that Borgia held the arms of [Gethin] Richards and bent it behind his back, that was a lie. Borgia did not do that. I don’t want to die with that lie on my lips. The rest of it was true.”

Mazzano, age nineteen, was the first to leave. He prayed with Father Kelly and held a silver crucifix as he was led to the electric chair. When he saw his old jailers Carl Repp and J. Henry Bair among the one hundred witnesses in the observation room of the death chamber, he cried out, “Tell my friends in Akron I died game.”

Attendants strapped Mazzano’s chest, arms and feet to the chair and applied electrodes to his right leg and head. Asked if he had any final words, a blindfolded Mazzano shook his head and began a quiet prayer. In a gruesome account, the Beacon Journal described the young gangster’s death:

Dr. Kramer stepped off the platform, into the booth at the side of the room and there pressed a button which gave the signal in the dynamo room. Three guards there pulled three levers, two of them being blanks, the third sending the current into Mazzano. It was just 12:05 when a sound as of a lever striking metal was heard, a low whining hum followed and Mazzano’s body strained against the straps, and then relaxed. Once again, after a pause, the current was turned on, and for the third time and at the last contact, the electrode on the leg turned into a white flame and a curl of smoke went up where the flesh and hair burned.

Dr. Kramer pronounced the inmate dead, undertakers removed Mazzano’s body for burial at Mount Calvary Cemetery in Columbus and prison guards immediately prepared the death room for the next execution.

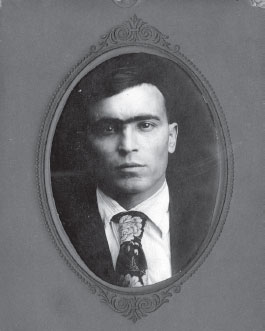

Frank Mazzano was executed on February 21, 1919, for the murder of Patrolman Gethin Richards. “Tell my friends in Akron that I died game,” he cried out in the death chamber. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection (State Archives Series 1000 AV).

Borgia, age twenty-four, who had converted to the Presbyterian faith in prison, walked with Reverend Thomas O. Reed toward the electric chair but began to crack as he neared the double doors to the death chamber. Two guards had to support his bulky frame while Borgia stepped warily onto the platform and stared wide-eyed at the lethal apparatuses in the room. Attendants strapped him to the chair, attached electrodes to his body and placed a black veil over his head.

Asked if he had any final words, Borgia replied in broken English, “I want to say an innocent man dies. Mazzano lied about me. I don’t think it right for me to die. I am innocent.”

“Is that all you have to say?” Kramer asked.

“That’s all I have to say,” Borgia replied.

Moments later, the hum of electricity filled the room. Borgia’s body convulsed, relaxed and convulsed. After two contacts, Borgia was declared dead, and his body was removed from the room. Witnesses somberly filed out of the observation room to leave the prison.

The Akron Press, as sensational as ever, described a grisly postscript to the public execution. After Borgia’s body was carried away, a man identified only as “prison undertaker Shaw” later claimed that the gangster revived. “His heart was thumping away like hell,” Shaw said. The attendants quietly returned Borgia to the empty room without any witnesses and turned on the juice again. “They were so excited on discovering he was still alive they gave him a third shock that burnt the hell out of him.”

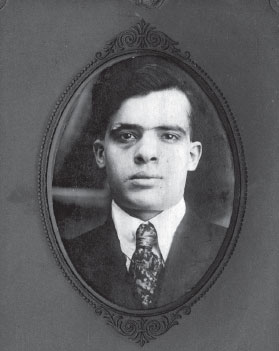

Gang leader Rosario Borgia was electrocuted on February 21, 1919, for the murder of Patrolman Gethin Richards. He proclaimed his innocence until the end. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection (State Archives Series 1000 AV).

Borgia’s brother Dominick, who lived in Rochester, New York, claimed the body and had it transported to his hometown, where the gangster was buried at Riverside Cemetery. Newly widowed Filomena Borgia soon discovered that “her man Rosario” had cut her out of his will and bequeathed his entire estate to his brother.

Three members of the Furnace Street gang had been executed. One was waiting on death row. Two others were serving life sentences. Things were beginning to get back to normal in Akron.

Two weeks later, three more cops were shot.