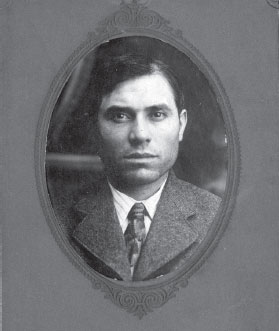

Patrolman George Werne was shot to death on March 9, 1919, off Hickory Street near the railroad tracks while he and two other officers investigated the overnight theft of chickens from coops. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

Thieves were stealing chickens along Hickory Street, and neighbors were angry. Michael Iamme, the latest victim, heard a noisy disturbance around 2:00 a.m. on Sunday, March 9, 1919, in his Tarbell Street backyard and stepped out to investigate, but his wife, Julia, urged him to call the police. Officer John Goodenberger quickly arrived at the scene and discovered that someone had cut the locks and hinges off Iamme’s coop and stolen sixteen chickens from the property along the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad tracks.

After daybreak, Iamme warned his neighbor Mary Kleinmetz about the crime and urged her to be careful. She was emptying a pail of water in her backyard around 8:30 a.m. when she noticed strangers approaching. “I saw these three men come up the track, and when they got opposite the Iammes’ coop, they stopped, looked at it and smiled, and then walked on towards the west,” she later testified.

Kleinmetz told her sister, Amelia Nuss, who lived next door, and she called police to report, “There are three suspicious-looking men on the railroad crossing on Hickory right now.”

Patrolmen George Werne, Will McDonnell and Stephen McGowan pulled up in a squad car, spotted the men at Hickory and Ravine Street and went to question them. Italian Americans Panfilio “Andy” Damico, his brother Vincenzo Damico and Pietro “Peter” Cafarelli stopped to face the plainclothes officers.

“You are under arrest,” Werne told the men, flashing a badge.

McDonnell was the first to see one of the suspects raise a revolver. “Shoot! Quick!” the officer warned his colleagues. In an unexpected, chaotic, life-and-death struggle, the cops grappled furiously with the men as a fusillade of shots shattered the Sunday morning calm.

Four bullets struck McDonnell, piercing his jaw, back, left shoulder and leg. McGowan was shot in the back, a slug puncturing his right lung. Another bullet hit Werne in the neck, severing his jugular vein. At least two of the officers managed to fire off shots before collapsing to the ground.

Panfilio Damico, age thirty, a rubber worker at Goodyear, made a mad scramble down the ravine and plunged into the Little Cuyahoga River to swim across. His brother Vincenzo, age twenty-four, a laborer, followed the same frenzied path and also jumped into the strong current. Cafarelli, age twenty-nine, who owned the nearby grocery at 115 North Maple Street, ran down the embankment in a panic but reconsidered his actions and climbed back up to the tracks just as other officers arrived.

McDonnell, McGowan and Werne were rushed to Akron City Hospital. The patrolmen’s wives were notified about the shootings before or during church services at St. Mary, St. Vincent and St. Bernard.

Werne, age thirty-two, was pronounced dead on arrival, the fifth Akron cop to be slain in fifteen months. He left behind a widow, Anna, age twenty-nine, and three children: Marie, eight; Richard, four; and Pearl, six months old.

“Patrolman Werne was slain by a single bullet,” coroner Carl Kent announced after an autopsy. “It came from a 32-caliber automatic revolver. The bullet entered the right side of the neck and severed the spinal column of the fourth cervical rib. I am of the opinion that Werne met with instant death.”

Lieutenant Frank McAllister; Detective Charles Doerler; Detective Patsy Pappano; Patrolmen Jacob Bollinger, Joe Petras and Eugene Murray; and Sheriff Pat Hutchinson rushed to Hickory Street after hearing reports of gunfire. Motorcycle cop Walter Horn saw Vincenzo Damico running near the river and fired a shot that struck his left arm. Bleeding and soaking wet, Damico broke into a cellar at 211 Mustill Street in an attempt to hide, but a neighbor alerted officers, and Horn, McAllister and Murray pulled him out at gunpoint. Police took Damico and Cafarelli to headquarters for questioning.

“I ought to give you what you deserve right here,” said Detective Ed McDonnell, whose brother was fighting for his life. “I’m an officer and will let the law take its course.”

Patrolman George Werne was shot to death on March 9, 1919, off Hickory Street near the railroad tracks while he and two other officers investigated the overnight theft of chickens from coops. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

Edward McDonnell was promoted to chief detective and then captain before retiring in 1933. He died following appendix surgery. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

Arraigned in police court before Judge Lloyd S. Pardee on charges of first-degree murder, Cafarelli pleaded not guilty, but Damico refused to cooperate. Pardee entered a not guilty plea for him.

“I don’t care,” Damico said. “I don’t care what you do with me.”

Police took Damico and Cafarelli to City Hospital to see if the wounded officers could identify them. A bullet in his lung, Patrolman McGowan, age thirty-five, looked up from his bed when cops escorted Damico into the room. “I wished I had a gun,” he said. “I’d shoot you right where you stood. That’s the man who shot me.”

At Will McDonnell’s bedside, Cafarelli begged, “Please don’t tell them I did any shooting.”

“You rat,” replied McDonnell, age thirty-eight. “You sneaking rat. You were there and did some of the shooting.”

Police officers and armed posses searched the Hickory Street neighborhood for more than thirty hours but couldn’t find the third suspect, Panfilio Damico. After he swam across the river, he vanished into thin air. Tips poured in after a $500 reward—dead or alive—was offered for the arrest of the five-foot-seven, 160-pound fugitive, but he never was captured. Authorities speculated that he escaped to Italy. Besides abandoning his brother, he deserted his wife, Margherita, who filed for divorce a year later and married another Italian.

Speculation immediately arose that the shootings were related to Rosario Borgia’s Furnace Street gang. Investigators downplayed a connection, though, believing that the Damico brothers were petty thieves. There were unusual ties, however. The Hickory Street shootout was only a few blocks away from Furnace, and Patrolmen George Werne and Will McDonnell were the first Akron officers to arrest Borgia in 1916.

“Rosario Borgia had the right hunch,” McDonnell said at the hospital. “Borgia told me when I saw him a few hours before his execution that I’d better watch out or someone would get me. I didn’t think, however, that it would come so soon.”

Initially given a slim chance for survival, McDonnell and McGowan recovered from their wounds and enjoyed long careers with the force.

The community rallied around Werne’s grieving family. Akron rubber executives C.B. Raymond of Goodrich, C.W. Seiberling of Goodyear and William F. O’Neil of General pledged $250 apiece to pay off the mortgage on the Werne house. The Akron Beacon Journal established a fund that collected more than $3,300 in three weeks. The American-Italian League of Akron raised $200 for the widow and children.

“We deeply regret the crimes that some of our people have committed, and desire to make it known to the public that these people who have no regard for law and order do not represent the better class of Italians,” said Akron banker Francis S. Massimino, league president. “We shall do all in our power to run down these fellows responsible for the disgraceful crimes committed.”

On March 12, the first anniversary of the death of Gethin Richards, two dozen officers escorted Werne’s casket from the family home on Marcy Street to St. Bernard Catholic Church to Holy Cross Cemetery. Pallbearers were Sergeants Edward Heiber, Edward Heffernan and Patrick Raleigh and Patrolmen Eugene Murray, Henry Bergdoll and John McMenamin. In his eulogy, Reverend Joseph M. Paulus noted, “Society must protect itself, law must be respected and obeyed and criminals must be punished.”

Cafarelli and his wife, Anna, had four young children—Elizabeth, seven; Adeline, five; Fannie, three; and Dominic, six months—with a fifth, Grace, on the way. The family rented apartments at the grocery to the Damico brothers. A christening party for the infant Dominic was planned on the day that Werne was killed, and investigators theorized that Cafarelli and his tenants raided the coop to serve chicken at the reception. Cafarelli said that his wife bought chicken for the christening, but Patrolman Patsy Pappano reported finding a burlap bag with feathers inside, plus locks and hinges that may have come from the coop.

Cafarelli insisted that he didn’t own a gun and never fired a shot. He maintained that he was a victim of circumstance and that Will McDonnell had confused him with gunman Panfilio Damico. The only reason he was on the tracks was that the Damico brothers were shaking him down for cash, he said. “I did not want to go out that morning,” he said. “First they said to go and get some fresh air, and when I said I did not want to leave because the baby was sick, they said I had to go out, they forced me to go out.”

He said he tried stopping twice, but the brothers pushed him along. Eventually, Panfilio turned to him and said, “You know the purpose we came down here for,” Cafarelli said. The brothers took two checks for about fifty-five dollars and were just about to take the seventeen dollars in his pocket when the police walked up, he said.

Judge William J. Ahern presided over Vincenzo Damico’s trial, which opened on May 22. Prosecutor Cletus G. Roetzel, back from military service, handled the state’s case. Attorney Rolland Jones led the defense.

Jones argued that fugitive Panfilio, not Vincenzo, fired the fatal shots. Furthermore, he said Panfilio fired in self-defense, thinking the plainclothes officers were hobos intent on robbing them. “The three officers were brigands, assassins, by not showing their badges,” Damico said. “I did not see any badges.”

Jurors deliberated forty minutes May 26 before finding him guilty. Jailers found Damico weeping on the cell floor. “I kill nobody,” he cried after being sentenced to death. He was taken June 2 to the death house, where Furnace Street gangster Paul Chiavaro, the prisoner in the next cell, greeted Damico in Italian.

Judge William Ahern presided over the Peter Cafarelli and Vincenzo Damico cases. He died unexpectedly at age thirty-eight. Author’s collection.

Paul Chiavaro was executed on July 24, 1919, for the murder of Patrolman Gethin Richards. He died with a smile on his lips. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection (State Archives Series 1000 AV).

The execution of Chiavaro on July 24, 1919, was almost an afterthought. Only seventeen witnesses were present as the thirty-one-year-old walked to the death chamber with Reverend Francis Louis Kelly. A serene Chiavaro prayed, kissed a crucifix and wore a faint smile as attendants strapped him to the electric chair.

“Have you anything to say before the sentence is executed?” Warden Preston E. Thomas asked.

“Nothing to say,” Chiavaro said. Switches were thrown, electricity hummed and Chiavaro died at 12:09 a.m. with a smile on his lips.

Cleveland attorney Benjamin D. Nicola, who had filed several motions in an effort to spare his client, was heartbroken. “It is a mistake, I am sure, to put Chiavaro to death,” he said. “I believe he is innocent.”

The execution of Vincenzo Damico, age twenty-five, took place on March 31, 1920. The condemned man cried, “Mother Maria! Mother Maria!” as Father Kelly walked with him to the electric chair. The death house lights flickered at 12:06 a.m., and Damico’s body was taken to Calvary Cemetery in Columbus. “Nineteen men have been electrocuted during my regime here, and it is the first time that a man met his end crying,” Warden Thomas said.

Vincenzo Damico was executed on March 31, 1920, for the murder of Patrolman George Werne. He cried while being led to the electric chair. Courtesy of Ohio History Connection (State Archives Series 1000 AV).

Maintaining his innocence, Pietro “Peter” Cafarelli fought tooth and nail. He was convicted of murder in a June 1919 trial and sentenced to death in October, but the appellate court rejected the verdict and ordered a new trial because the defense had not been allowed to examine a list of six potential jurors.

In the second trial, which began on February 26, 1920, defense attorney Joseph V. Zottarelli argued that Cafarelli had feared for his life when Vincenzo and Panfilio Damico demanded his cash after forcing him down the railroad tracks. He actually felt relieved to see the plainclothes officers, he said. “Cafarelli regarded the arrival of these three men as an intervention of Divine Providence, and he said fervently to himself and his God, ‘My God, I thank thee for sending these men to save me,’” Zottarelli said.

On March 5, the jury convicted Cafarelli of first-degree murder with a recommendation of mercy, sparing him the electric chair. Judge Ahern sentenced him March 13 to life in prison. “All I have to say, your honor, is that I am innocent, and I am convinced that I can show my innocence yet,” Cafarelli said.

For more than ten years, Cafarelli tried to clear his name at the Ohio Penitentiary. Prisoner 48462 was a model inmate—polite, pious, orderly and obedient—working as a skilled mechanic in the machine shop. During a 1939 interview, the forty-year-old convict told a Beacon Journal reporter, “Maybe you will say in your paper that it was not I who fired the shot, that it was not I who carried the gun, but that it was Damico, and I have been many years here. I am old now.”

At least three jurors reversed themselves and lobbied state officials for a pardon. Former prosecutor Cletus Roetzel wrote to two Ohio governors to urge Cafarelli’s release, saying, “There is no doubt that Cafarelli is guilty as indicated by the evidence of the trial. I am convinced, however, that he did not fire the shot that killed Werne, and that he is not by nature criminally inclined.”

Pietro “Peter” Cafarelli, age forty-one, enjoyed one last visit with his wife and five children on April 21, 1930. Three hours later, a savage fire swept through the Columbus penitentiary, killing 322 inmates. Rescue crews found Cafarelli’s body in his locked cell. He was clutching a rosary when he died. “He was the best prisoner in the penitentiary,” Warden Preston E. Thomas sobbed to a reporter.