Needy people form a bread line outside Reverend Bill Denton’s Furnace Street Mission in the 1930s. The building at left once stood across the street and served as the lair of the Furnace Street gang. Courtesy of Furnace Street Mission.

Furnace Street cleaned up its act long ago. The formerly notorious neighborhood is home today to the Northside District, a cultural center of arts, dining, entertainment, shopping and recreation. The district’s attractions in 2017 included Luigi’s Restaurant, an Akron institution since 1949; Dante Boccuzzi Akron, an upscale restaurant owned by a famed Cleveland chef; Jilly’s Music Room, a concert club and tapas bar; Zeber-Martell, an art gallery and studio; Rubber City Clothing, a popular shop for Akron streetwear and accessories; Northside Lofts, luxurious living on the edge of downtown; and the Courtyard by Marriott, a hotel with a Prohibition-themed cocktail bar called the Northside Speakeasy.

Traveling farther east on Furnace Street, motorists can scarcely imagine what it was like a century ago. Most of the old buildings have been demolished, leaving vacant lots and overgrown woods. It’s like a giant broom swept away the original homes, saloons, brothels, pool halls, restaurants, coffeehouses, hotels, cigar stores, barbershops, tailors shops and confectioneries.

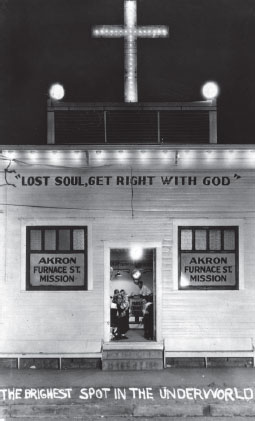

A little brick building topped with a big white cross is a reminder of yesteryear. The Furnace Street Mission chapel, which was constructed in 1962, replaced the original building where Reverend Bill Denton (1895–1982) established the “Brightest Spot in the Underworld” in the late 1920s. Denton set up a soup kitchen, provided clothes for the needy, operated a halfway house and preached the Gospel at the mission, which originally was located at 121 Furnace Street in Joe Congena’s former pool hall, the hangout of Rosario Borgia.

“I can remember as a kid being fascinated by a trap door in the back of the building floor that led to a meeting room, which was where the murders were planned,” said Reverend Bob Denton, Bill’s son and successor in the ministry. “Always wanted to explore that but Dad put the quietus to that.”

Captain Al “Fuzzy” Monzo (1915–2012), an Akron cop for thirty-six years, once explained to the younger Denton how the original building was moved to 140 Furnace. “He was a young kid who lived down here when the neighborhood was primarily Italian,” Denton said. “My dad enlisted a bunch of the kids—including him—to pick up the building, put it on poles and roll it across the street to its final location—about where our drive is on the current property.”

Irony of ironies, the murderous Furnace Street gang’s old hideout became a place to save souls. The mission opened a halfway house for ex-convicts and established the nationally acclaimed Victim Assistance Program. Borgia definitely wouldn’t recognize the neighborhood today.

Giacamo Ripellino, better known as Frank Bellini, happily took over Borgia’s criminal enterprises and became one of the region’s most powerful gangsters over the next decade during Prohibition. Police connected him with bootlegging, prostitution and murder, but he never was convicted of any serious crimes. In fact, he was known for his generosity, donating money to poor Italian families. Bellini outwitted his enemies for years, but the fifty-two-year-old let down his guard on June 27, 1929. He and four friends were sitting outside his store at 106 North Howard Street when a large touring car pulled up, curtains parted on the windows, and three shotgun blasts struck Bellini. The car sped away and the gunmen escaped, never to be found. Police suspected that an old friend of Borgia’s was settling a score. Doctors amputated Bellini’s legs at St. Thomas Hospital, and he died of an infection June 28. More than three hundred people attended the rites at St. Vincent Church, which one newspaper described as “Akron’s first intimate glimpse of a gangland funeral.” Bellini was laid to rest in a bronze casket at Holy Cross Cemetery.

Needy people form a bread line outside Reverend Bill Denton’s Furnace Street Mission in the 1930s. The building at left once stood across the street and served as the lair of the Furnace Street gang. Courtesy of Furnace Street Mission.

Like so many of his customers, pool hall operator Joe Congena, age thirty-seven, met a violent death. Boarding at the home of Rosario and Rose Cusamano at 118 Furnace, he threatened to blackmail his nineteen-year-old landlady over allegations of marital infidelity with another tenant, Joe Catanio, age thirty-nine. On August 17, 1921, she lured Congena into the cellar, where Catanio killed him with four blows from a hatchet. Rose Cusamano initially alleged self-defense, but she and Catanio were convicted of first-degree murder.

Furnace Street gang member Salvatore Bambolo joined the U.S. Army, got married in 1920 and stopped hanging out with the wrong crowd. He moved to California, where he operated a fruit and nut business before retiring in 1970. He was eighty-four years old when he died in Lodi, California, in 1980.

Bambolo’s brother-in-law, Calcedonio Ferraro, registered for the military draft in 1918 after being charged with cracking a safe at the Acme store on North Hill. Following the war, he was convicted of burglary and grand larceny. Upon parole from prison, he settled in Chautauqua, New York, where he lived with his wife, worked as a finisher in a furniture factory and maintained a low profile, dying in January 1967 at age eighty-six.

Filomena Borgia disappeared from the public eye after the execution of her husband, Rosario Borgia. After being shut out of the gangster’s will, reportedly worth $10,000 (about $191,000 in 2017), she quietly walked away. Official documents shed little light on her departure from Akron. Someone with her name died in 1923 in New York, but that might be a coincidence. Perhaps she remarried using one of her husband’s many aliases. If so, one can only hope that she became more selective in her choice of men. But wait a minute. Census records from 1930 show a Filomena Borgia living in New York with a Dominick Borgia. Rosario’s beneficiary was his brother Dominick. You don’t suppose…could it be?

Pallbearers carry the casket of Frank Bellini following his funeral in 1929. The Akron gangster was gunned down outside his store on North Howard Street. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

The Furnace Street Mission, the “Brightest Spot in the Underworld,” opened in the late 1920s in Joe Congena’s old pool hall. Rosario Borgia plotted the murder of Akron police officers at the hangout in 1917. Author’s collection.

Private investigator George Martino closed his detective agency in 1919 and got caught in a 1922 liquor-smuggling racket using the Lynn Drug Company as a front. Federal agents seized 139 cases of liquor in the showroom of the East Market Street business near Union Depot. In 1923, he was sentenced to eighteen months in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta for conspiracy to defraud the government in violation of the Prohibition law. His name disappeared from Akron newspapers.

Michael Fiaschetti, the New York detective, received two gold medals in September 1919 from Mayor I.S. Myers and the Akron Chamber of Commerce “for exceptionally skillful work” in helping to solve the police slayings. The Italian Squad director drew the ire of Akron police, however, when he wrote a 1929 article for Liberty magazine in which he took most of the credit for cracking the case. Officers objected, saying Fiaschetti mostly served as an interpreter in 1918. “If Fiaschetti’s other stories are as authentic as this one about the Borgia gang, I pity the poor readers,” Detective Edward J. McDonnell noted. Fiaschetti penned a few autobiographies and retired from the force to become a private detective. He died at age seventy-eight on July 29, 1960, at a VA hospital in Brooklyn.

Patrolman Walter Horn was seriously injured in July 1919 when his motorcycle crashed into an automobile. He was allowed to resign from the force in November 1920 after he was charged with conduct unbecoming an officer and neglect of duty. He died on November 23, 1964, in Detroit, where he had moved in 1940 to work for the Ford Motor Company.

Detective Harry Welch was named the chief of the detective bureau when it was organized in 1921. He retired from the force on January 1, 1928, after thirty-one years in the department and ran a private detective agency for a few years. “Other good men may come and may fill Welch’s job very efficiently, but for the old-timers, the gap in the roster made by Welch’s resignation will never be made up,” Captain Frank McGuire said. Welch suffered a heart attack on January 17, 1933, while driving his car on Glendale Avenue and died en route to a hospital. He was sixty-two years old.

Detective Bert Eckerman, who joined the force in 1903, retired in 1932 after twenty-nine years on the job. At his testimonial dinner, Eckerman told the audience, “Of course I thank you and there isn’t much else to say, but maybe you’ll remember this, or maybe some of the newer police officers here and others who are to come, will remember: I wouldn’t lie on a man. I wouldn’t send a man to the penitentiary unless I knew he was guilty…and there was never a man come out of that penitentiary, if I sent him there, who wasn’t willing to shake hands with me.” The 280-pound detective died of pleurisy in 1943 at age seventy-five.

Edward J. McDonnell was named chief of the detective bureau in 1928 after Welch retired and was promoted to captain in 1930. In celebration of McDonnell’s twenty-fifth anniversary with the force, more than five hundred people attended a testimonial dinner in his honor on February 1, 1933, at the Mayflower Hotel. “What success I have had, if I’ve had any, I owe to the men in the detective department and to the good citizens of Akron,” he told the crowd. “From the bottom of my heart, I want to thank each and every one here for making this one of the most important events of my life.” McDonnell had an appendix operation in May 1933 and died unexpectedly a week later of a blood clot to the heart. He was only forty-nine. “The days of a good life are numbered, but a good name continues forever,” Reverend James H. Downie eulogized at St. Vincent.

John Durkin was one of only six patrolmen when he became a cop in 1883. “When I joined the force, there wasn’t a streetcar in Akron,” he recalled. “There were no electric lights and Market Street was the only thoroughfare in town which boasted paving.” He remained on the job for forty-seven years—a department record—and served as chief for thirty years until failing health forced him to retire on February 1, 1930. Colleagues hailed him for revolutionizing the department. Durkin was seventy-nine when he died on April 14, 1939. “As chief of police, Durkin adhered to a simple code,” the Beacon Journal noted. “On matters which he considered of secondary importance, he gave the town as much or as little law enforcement as it wanted, but he insisted upon the fundamental virtues of honesty and bravery at all times. The results of this course were unquestioning loyalty from his men and the respect of the people.”

Detective Pasquale “Patsy” Pappano spent twenty-seven years with the department, retiring in 1944. “I’ve had my fill of pounding pavements and chasing criminals,” he explained. “I feel I’ve earned a good, long rest—and I intend to take one.” The Italian American cop was sixty-seven when he died after a short illness on January 31, 1960. “Patsy’s unique qualifications and reputation often induced police of other cities to ask for a loan of his services on tough cases,” reporter Kenneth Nichols recalled. “The hard shell he showed toward the lawless was just that—a shell. He was a kindly, good-natured man, a trencherman who could make a plate of Italian food vanish as a magician does a rabbit.”

During his first decade on the force, Stephen McGowan was shot three times and dodged at least another dozen bullets. In 1929, he helped capture gangster Pretty Boy Floyd, who was hiding under a bed at a Lodi Street home. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1930 and captain in 1942. McGowan loved being a policeman and refused to retire. “What would I do?” he said. “Sit in a rocking chair on my front porch? Everything that is dear to me is here in Akron and at the police station.” He had nearly forty-five years of service when he died of a heart attack behind the wheel of his cruiser on February 23, 1963. He was seventy-nine.

Unlike McGowan, Detective Will McDonnell had no qualms about dying on his front porch. After nineteen years of service, the detective retired on pension in May 1932, still carrying two slugs in his body from the 1919 shootout. “I’ve had enough excitement to last me a long time,” he once told a reporter. McDonnell died of a heart attack on August 30, 1953, on a porch swing at his Gale Street home. He was seventy-two.

Louis Hunt turned five years old the day his father, Joseph Hunt, a rookie officer, died on January 12, 1918. “I’ll grow up and I’ll be a cop—a good cop like my daddy,” the little boy vowed during the funeral. In 1938, Louis took the civil service exam and joined the force a year later at age twenty-seven. “My father never had a chance,” he explained. “I want to take up where he left off.” Somewhat surprisingly, his widowed mother, Adale, was in favor of the move. “It’s a dangerous life, but a good policeman is a fine citizen,” she told a reporter. The younger Hunt served thirty-three years on the force, working in the traffic division, vice squad, patrol division and communications before retiring as a sergeant in January 1974. “I’ve enjoyed working as a policeman,” Hunt said. He was seventy-eight when he died on May 25, 1991.

Judge Ervin D. Fritch retired in February 1943 after more than twenty-eight years on the Summit County Common Pleas bench. More than four hundred attended an Akron Bar Association banquet honoring him as “the best trial judge the county ever had.” In 1957, Fritch created a fund at the University of Akron that awards annual scholarships to students based on academics, financial need, moral character and ability. “No judge in our history has exceeded Judge Fritch in judicial interest, judicial temperament, judicial ability and the courage to meet the issues of the day,” retired Firestone executive Joseph Thomas noted in October 1963 during Fritch’s ninetieth birthday celebration. Fritch, a small man with a big brain, died on March 24, 1969, at age ninety-five.

Judge William J. Ahern Jr., who presided over the Peter Cafarelli and Vincenzo Damico cases, served a decade on the Summit County Common Pleas bench before stepping down in May 1923. He was only thirty-eight years old when he died unexpectedly on July 21, 1924, of heart failure after a lengthy battle with pneumonia. Judge Lionel S. Pardee, who succeeded Ahern, cried when he heard the news. “It is too bad that a young man with such a brilliant future had to die,” Pardee said. “Judge Ahern will be missed very much. He was a good friend of mine, and I always found him honest, courageous and a worker.”

Cletus G. Roetzel served two terms as Summit County prosecutor before resuming his law practice in Akron. In 1949, Pope Pius XII named Roetzel a Knight of the Order of St. Gregory the Great. He was the senior partner at Roetzel and Andress, a law firm that bears his name, when he died on October 15, 1973, at age eighty-four. He had served in leadership positions at the Akron Art Institute, Akron Bar Association, Catholic Service League, St. Thomas Hospital and the University of Akron. “The life he helped breathe into these institutions is his proud and continuing legacy to Akron,” the Beacon Journal eulogized.

Former prosecutor and assistant prosecutor Charles P. Kennedy, who helped Roetzel convict the Furnace Street gang, formed the Ormsby & Kennedy law firm and was elected president of the Akron Bar Association in 1928. The group saluted him in 1960 for serving fifty-four years as an attorney. He died on March 26, 1965, at age eighty-one in his home in Sarasota, Florida.

Rosario Borgia’s defense attorney, Abram E. Bernsteen, enjoyed many victories after that infamous loss. President Warren G. Harding nominated him in 1923 as U.S. attorney for the northern district of Ohio, and he served until 1929. Bernsteen finally moved out of his parents’ home and married his assistant, Irene Nungesser. He gave serious consideration to running for governor in 1928 but thought better of it. Bernsteen died on April 5, 1957, of a heart attack at the Cleveland Clinic. He was eighty.

Barberton attorney Stephen C. Miller, who assisted Bernsteen with the Borgia case, barely outlasted the Furnace Street gang. Regarded as a brilliant legal mind, Miller practiced law for more than three decades before dying of diabetes on October 9, 1923, at age sixty.

Attorney Seney A. Decker did not pay a political price for mishandling the stay of execution for Pasquale Biondo in 1918. The following year, he was elected Barberton mayor and served two terms. He also was the first president of Barberton Kiwanis and Barberton Eagles. Decker was found dead in his bed of an apparent heart attack at age sixty-one on December 30, 1936.

Frank Mazzano’s defense attorney Orlando Wilcox served as Cuyahoga Falls city solicitor and director of Cuyahoga Falls Savings Bank and the Falls Savings & Loan Association. He died on January 17, 1932, at age eighty after suffering a stroke. “He was thorough as an advocate, wise as a counselor, always respected as an antagonist, and not infrequently to be feared,” attorneys C.T. Grant, W.E. Slabaugh and Harvey Musser noted in a prepared statement mourning the loss of their colleague.

Amos H. “Tiny” Englebeck, Wilcox’s assistant in the Mazzano case, went on to serve as chairman of the Republican Executive Committee and president of the Summit County Board of Health. He was monarch of Yusef-Khan Grotto, potentate of Tadmor Temple, sovereign grand inspector general of Ohio and grand high priest of the Royal Arch Masons. After he died on September 11, 1952, at age sixty-six, local Masons honored his memory by naming the Amos H. Englebeck Lodge after him.

Reverend Francis Louis Kelly, Ohio Penitentiary chaplain for more than twenty-five years, retired in 1927 and died on February 10, 1932, at age eighty at the Dominican Fathers’ Home for the Aged in Minneapolis.

Cleveland attorney Benjamin D. Nicola, legal counsel for Lorenzo Biondo, practiced law for sixty years. He was named U.S. commissioner in 1930, appointed Cuyahoga County Common Pleas judge in 1948 and retired in 1964 at age eighty-five. He died on March 21, 1970, at age ninety-one in Aurora in Portage County.

Convicted murderer Lorenzo Biondo, alias James Palmieri, was sentenced to life in prison for the 1918 slayings of Joe Hunt and Edward Costigan, but it didn’t work out that way. In a shocking turn of events, Governor George White commuted the sentence on May 25, 1934, for reasons that remain mysterious. Biondo, age thirty-five, was freed from the Ohio Penitentiary, placed on the Italian ocean liner SS Rex in New York and ordered never to return to the United States. Former judge Ervin D. Fritch and former prosecutor Cletus G. Roetzel weren’t informed of the parole and didn’t find out for several years. “The police department would certainly have left no stone unturned to keep Biondo in prison if it had had any knowledge of the parole move,” Detective Inspector Verne Cross fumed in 1938. A free man, Biondo returned to his native land just before World War II engulfed Europe. His final fate remains unknown to this day.

Anthony Manfriedo wasn’t as lucky. Sentenced to life in prison at age twenty-one for being the lookout when Costigan and Hunt were slain, Manfriedo was locked up and forgotten for nearly fifty years. Beacon Journal reporter Carl J. Peterson found him in 1965 at the London Correctional Institution. Manfriedo, age seventy, a prison nurse for two decades, had just requested parole for the fifth time. “I’m not getting any younger and I don’t want to die in prison,” he told the reporter. “I want to enjoy a freedom that I have had so little of in my lifetime.” Manfriedo was apologetic for his role in the killings. “It was my own fault,” he explained. “I was a young kid. Just got here in this country and didn’t think. I’m not mad at anybody now. I don’t think I have an enemy in the world.”

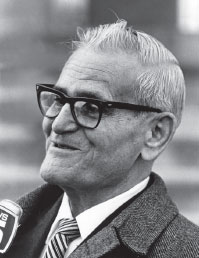

Former Akron gangster Tony Manfriedo is happy to be a free man after receiving a state pardon in 1965 following nearly fifty years in prison. From the Akron Beacon Journal.

On November 22, 1965, Governor James Rhodes pardoned Manfriedo and expunged his criminal record. “I never thought this day would come,” Manfriedo said. “I hope all the time. I never give up hope.” Roetzel, the former prosecutor, and Fritch, the former judge, had recommended parole as early as 1950, to no avail. “I think it’s a good idea,” Roetzel said. “Actually, it should have been done earlier. I’m a very firm believer in comparative justice. It’s disturbing to me when one man gets a severe penalty and another, under similar circumstances, gets a lighter penalty.” Judge Fritch added, “I feel Manfriedo deserved to be freed. He’s the last of the Borgia gang left. I think he was in prison too long as it is.”

A gray-haired, bespectacled Manfriedo returned to Akron for a visit on Tuesday, November 30, and was amazed with what he saw. “This not the same city,” the Sicilian native told reporter Carl J. Peterson in broken English. “I never believe Akron look like this!” One of the few places that looked familiar was the Goodrich plant, where he worked in 1917 before falling in with the wrong crowd. “I don’t know anyone here anymore,” Manfriedo shrugged. “It’s been too long.”

Manfriedo returned to Columbus and found a job at a nursing home. His left eye had to be surgically removed in 1967 because of a tumor, but in his last known interview at seventy-two, he told a reporter, “I would rather be a free man with one eye—and enjoy this good fresh air—than be in the prison with both eyes.”