On Monday 30 May 1927, a cool day with showers forecast, New Yorkers were gathering for the annual Memorial Day parades around the city. It was only nine years since the end of the great European war, into which America had been so reluctantly drawn, and Europe had suddenly become closer than ever before. Precisely ten days earlier, Charles Lindbergh had completed the first solo flight across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis, and no one had yet stopped celebrating. Front pages around the country reported that Lucky Lindy had been mobbed in London, greeted by rapturous crowds of 150,000. Few Americans were talking about much else than the newest national hero, but in New York that day different kinds of mobs were about to gather.

Around 8 a.m., a group of Italian immigrants living in the Bronx set out for the elevated train on their way to Manhattan to join the parade. But they were not going to honour the American soldiers who had died in the service of their country. They were supporters of Mussolini, planning to join four hundred American Fascists who were marching in Manhattan’s Memorial Day parade as part of the official Fascist movement in America. They had been invited by the parade’s organisers, to the outrage of many anti-Fascists, including Italian nationalists and anarchists who threatened violence if the invitation wasn’t rescinded. It wasn’t.

Like all his fellow Fascists intending to march that day, Joseph Carisi was wearing the blackshirt uniform, sporting leather boots, jodhpurs, a black cap, and carrying a steel-tipped riding crop. When he stopped to buy a newspaper, Carisi was jumped by two men, stabbed in the neck and left to die on the sidewalk. Another Fascist, Nicholas Amoroso, who was running either to catch up with his group or away from the killers (reports vary), was shot four times, once right through the heart. One of the two murdered men had served in the American army during the Great War, the other with the Italian army, papers reported.1

The parade they had meant to join took place without them, a Fascist delegation of several hundred that was guarded by police ‘to avert disorder’.2 After the parade the American blackshirts returned to their headquarters, in the heart of Times Square. There another of the Fascists, standing outside, was set upon by three men. He defended himself with his riding crop, as his fellow blackshirts charged out brandishing clubs and whips, chasing the assailants through theatre crowds in Times Square, who fled as ‘the black-shirted mob tore through traffic’.3 A hundred Fascists, reported the New York Times, rushed the attackers; a ‘melee’ ensued that was quickly dispersed by the police.

There was also violence in Brooklyn, where a parade of Fascisti marched from the Angelo Rizza Fascista League at 274 Troutman Street, in Bushwick. The LA Times reported ‘several hundred men’ were parading, ‘including forty or fifty in the black shirt uniform’. Fights broke out between supporters and protesters mingling on the sidewalks, and an anti-Fascist was found lying on the ground, stabbed in the back. He survived, and identified a Fascist as his assailant. Accompanied by thirty police reserves to forestall violence, the marchers made their way through Brooklyn, stopping at the Wilson Avenue station, where the Fascisti came to attention and gave the Fascist salute. They ended at a Roman Catholic church, where the priest blessed them under large American and Italian flags while the police remained on guard.

The biggest outbreak of violence that Memorial Day, however, occurred in Queens, where it centred around a different right-wing group: not Italian-Americans, but the self-proclaimed ‘one hundred percent American’ kind.

By 1927, the Ku Klux Klan had spread across the United States since its rebirth in Georgia twelve years earlier. The first Klan was formed in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, as former Confederate soldiers in Tennessee created a secret society to promote white supremacism and terrorise the newly freed slaves in the South during the Reconstruction Era. (The name is generally believed to have originated from the Greek word for ‘circle’, kuklos, while ‘klan’ pays homage to the mystified Celtic heritage supposedly shared by white Southerners.) Within a decade or two, the first Klan had been successfully suppressed by law enforcement, and died out by the turn of the century. But in 1915, it was resuscitated in Georgia, and by the early 1920s the Second Klan had achieved a powerful political presence in the United States, not only in the South, but across the country.

The Klan had an active presence in New York City and Long Island by 1927, with favourite slogans, which they even attempted to copyright at various points. That year the Klan was ‘call[ing] attention to the fact that it first announced the program of one hundred per cent “Americanism” and of “America first”’.4 They were not, in fact, the first to adopt these mottos, as this book will show: in 1927, both phrases had been around for a decade or more.

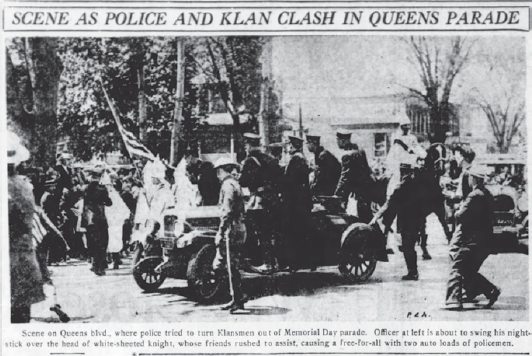

But as far as the Klan – busily copyrighting hate – was concerned, ‘America first’ belonged to them, and on Memorial Day in Queens a thousand or so of them had gathered to march, many in white robes and hoods. They were accompanied by four hundred women from the so-called ‘Klavana’ (the ‘feminine branch’ of the Klan). Some of the reported 20,000 spectators in Queens that day objected to the Klan’s presence, as others defended their right to march; scuffles broke out, and it turned into a riot. ‘Women fought women and spectators fought the policemen and the Klansmen, as their desire dictated.’ Klan banners were shredded, and ‘five of their number’ were arrested, said initial reports, while a few others were caught up in the confusion as well.5

Although the police in Queens had been ordered to keep the Klan in check, ‘the Klan worsted detachments’ of police ‘on four separate occasions during its four-mile march and surged triumphantly past the reviewing stands, little the worse except for a number of tattered robes and dismantled hoods and five marchers in the custody of the police’.6

The police commissioner announced that neither American Fascists nor the Ku Klux Klan should have been allowed to parade in the first place. ‘Ku Klux Klan members involved in the Memorial Day parade riot in Queens, “clearly were guilty of a breach of faith with the police”,’ said the commissioner. ‘“Neither the Klan nor the Fascisti have a proper place in a parade dedicated to the soldier dead of the United States.”’7 Within a week, New York had banned any public appearance by either ‘the white-robed Ku Klux Klan’ or ‘the black-shirted Fascisti’.8

After the riots, public support for the Klan was voiced in the New York area more than once. One Long Island citizen complained that ‘the police were grossly to blame for this disgraceful affair’, calling their ‘interference’ in the clashes ‘a detestable outrage’. ‘The Klan had a perfect right to march and thank God they exercised that right.’9 The tone of more than one local report suggested the Klan was the injured party: Klansmen and women ‘ran the gauntlet of attacks’, which ‘the police were powerless to prevent’, wrote one upstate New York editorial. ‘Many Klansmen had their robes torn off and many of the men and women marchers were struck by flying missiles.’10

The Klan, meanwhile, blamed the police for being Catholic. In a circular headed ‘Americans assaulted by the Roman Catholic Police of New York City’, the Klan protested against ‘Native born Protestant Americans’ being ‘clubbed and beaten when they exercise their rights in the country of their birth’. Casting themselves as the victims of police brutality, they added: ‘We charge that the Roman Catholic police force did deliberately precipitate a riot,’ beating ‘defenseless Americans who conducted themselves as gentlemen under trying circumstances’. As far as the Second Klan was concerned, Catholics couldn’t be loyal Americans because their higher allegiance was to the Pope.

In the days after the riot, the New York Times revealed the names of a total of seven men who had been arrested in Queens. Five of them were identified as ‘avowed Klansmen’ who’d been marching in the parade,11 and were arrested for ‘refusing to disperse when ordered’. A sixth was a mistake: he’d had his foot run over by a car and was immediately released. The seventh, a twenty-year-old German-American, was not identified in the press as a Klansman. The reports only stated that he was arrested, arraigned and discharged.12 No one knows why he was there, but it appears that he wouldn’t leave. His name was Fred Trump.

It meant nothing at the time.