Unlike the ‘American dream’, ‘America first’ was always a political slogan. What both expressions shared were their attempts to identify a national value system, and they emerged at the same moment in America’s history – as it came into its own as a world power at the beginning of the twentieth century, and began debating in earnest the role it would play in the world. By no coincidence, the two moments of crisis in defining these terms arose when the United States faced the urgent question of how to respond to each of the century’s world wars.

‘America first’ was also like the ‘American dream’ in not suddenly being invented by an individual, although it was popularised by one. The phrase appears as a slogan in the American political conversation at least as early as 1884, when an Oakland, California, paper ran ‘America First and Always’ as the headline of an article about fighting trade wars with the British.

A Wisconsin congressman gave an 1889 speech declaring that while there was no danger of war between America and Germany, there was also ‘no doubt of the loyalty of German-Americans to the land of their adoption … We will fight for America whenever necessary; America first, last and all the time; America against Germany; America against the world; America, right or wrong; always America.’1

The New York Times shared among its ‘Political Notes’ in 1891 the observation made by ‘a wild Western turnip-fed editor out in the State of Washington’ that ‘the idea that the Republican Party has always believed in’ was ‘America first; the rest of the world afterward’.2 The Republican Party agreed, adopting the entire phrase as a campaign slogan by 1894. The Morning News in Wilmington, Delaware, described a Republican ‘monster parade’ of victory, in which jubilant Republican voters wore ‘America First’ badges in honour of ‘the redemption of the state from Democratic misrule’: ‘nearly every man seen on the street wore a badge bearing the words “America First, the World After”’.3

That same year a politician responded to the toast of ‘Government by the People’ by saying he ‘believed in America first’, that ‘patriotism is loyalty to America first’.4 By 1899, there were a few scattered references in regional papers to an ‘America First Committee’, its official purpose unclear.5

‘See America First’ had become the ubiquitous slogan of the newly burgeoning American tourist industry by 1906, one that adapted easily into a political promise, as was recognised by an Ohio newspaper owner named Warren G. Harding, who successfully campaigned for senator in 1914 using the slogan ‘Prosper America First’; he would return to the motto before long.6

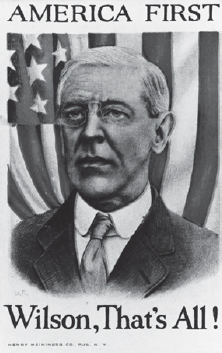

The expression did not become a national catchphrase, however, until April 1915, when President Woodrow Wilson gave a speech declaring: ‘Our whole duty for the present, at any rate, is summed up in the motto: America First.’ At that point, it took off.

Western Europe was a full year into the Great War, while the United States remained neutral. Although public sentiment veered strongly towards protecting fellow neutral nations like Belgium from German occupation, many Americans viewed the conflict as an imperialist quarrel between two equally unsympathetic foes. Despite a strong animus against what was widely perceived as a baldly nationalist venture by Kaiser Wilhelm, there was plenty of anti-British sentiment to balance that out. The sun had not yet set on the British Empire, and it was not at all clear to many Americans why they should support the nation they had fought so hard (and within the memory of living people’s grandparents) to overthrow. Irish-Americans in particular were outraged at the idea of an allegiance with Britain, as most of them had emigrated to America to escape conditions created by British rule, an offence that only deepened after the British government’s brutal response to the 1916 Easter Rising. Neutrality also meant that US citizens could contribute relief to victims in war zones, and the nation gave generously.

American neutrality was by no means always motivated by pure isolationism, in other words; it mingled pacifism, nationalism, anti-imperialism, anti-colonialism and exceptionalism – and it was widespread. Wilson gave many citizens the tuning note they sought in declaring America ‘too proud to fight’.

A Democrat who campaigned on progressive lines, Wilson had been president for three years when he gave his ‘America first’ speech with an eye on re-election a year later. This line has often been quoted, although almost never in association with its resuscitation a century later, and usually taken out of context from Wilson’s speech. Detail tends to be the first casualty of reproduction.

‘I am not speaking in a selfish spirit,’ Wilson began, ‘when I say that our whole duty, for the present, at any rate, is summed up in this motto, “America First.” Let us think of America before we think of Europe, in order that America may be fit to be Europe’s friend when the day of tested friendship comes.’ Wilson argued that America could demonstrate its friendship best not by shows of ‘sympathy’ for either side, but by preparing ‘to help both sides when the struggle is over’.

Neutrality didn’t mean indifference or self-interest, he insisted. ‘The basis of neutrality is sympathy for mankind. It is fairness, it is good will at bottom. It is impartiality of spirit and of judgment. I wish that all of our fellow citizens could realize that.’7

All of his fellow citizens evidently could not realise that, for the phrase was rapidly taken up without any of Wilson’s subtlety – or mendacity, depending on your perspective. Certainly the decision to maintain neutrality in the face of evil can be immoral, as history would demonstrate all too savagely within twenty years. Walter Lippmann, for one, now co-editing the New Republic, argued strenuously for America’s intervention in the war on the basis that bystanders could not affect the justice of the outcome, or protect democracy.

But Wilson had something else noteworthy to add in his 1915 ‘America first’ speech – a warning about being taken in by ‘fake news’.

Wilson told the country there was a growing problem with news that ‘turn[s] out to be falsehood’, or that is false in ‘what it is said to signify’, which, if the nation were ‘to believe it true, might disturb our equilibrium and our self-possession’. The country could not afford ‘to let the rumors of irresponsible persons and origins get into the United States. We are trustees for what I venture to say is the greatest heritage that any nation ever had, the love of justice and righteousness and human liberty’, and so it was vital that Americans defend that heritage of justice and freedom.

There were ‘groups of selfish men in the United States’ working to undermine that legacy, creating ‘coteries where sinister things are purposed’. But ‘the heart of America’ would stay true, Wilson was confident, and it should put America first by staying out of the conflict.8

Wilson explicitly differentiated ‘America first’ from self-interest and indifference, and it can’t reasonably be said that this speech enjoins isolationism per se. Nonetheless, he was campaigning on the basis of keeping America out of the war, and ‘America first’ was taken up in the name of isolationism almost instantly.

Some of his critics objected to the flexibility in Wilson’s use of the term ‘America first’. In November 1915, the president of ‘Friends of Peace and Justice’ challenged Wilson on what it meant in real terms to put ‘America first’, demanding: ‘What would “America First” mean if we had a President who was not a mere trickster in phrases?’ It would mean having a president who cared for ‘that mass of Americans who are living today in poverty or in fear of want, because of the robberies which are being perpetrated upon them by the highwaymen of modern finances’.

‘America first’ was a mere ploy, he added, to distract the people with flag-waving from the brazen corruption of ‘subservient politicians’ who served only the nation’s ‘mighty financial interests’, not its ordinary citizens.9 This unholy alliance between the ‘highwaymen of modern finances’ and the politicians who truckled to them was ‘the most extraordinary conspiracy’ to consolidate power in ‘the entire history of our Republic’.

Meanwhile the US Bureau of Education was creating an ‘America First’ campaign, with an explicitly assimilationist agenda. Its stated purpose was to encourage immigrants and new American citizens to put loyalty to the United States above allegiance to the nations they had left; but it also explicitly stated that no one expected, or desired, immigrants to reject their own culture, language or histories in order to embrace America’s. Arguments over whether English should be a compulsory national language flared; what it meant to be an ‘American’ in a country absorbing waves of immigration became an urgent question, the answer to which, for many, was to impose an American ethno-nationalism, one that upheld old prerogatives of white, Protestant, male establishment power.

By no coincidence, the American ‘melting pot’ as a metaphor for assimilation emerged during roughly the same period, comparing the mixing of immigrant communities together to the practice of melting different metals together in order to mint new coins – no less valuable, but in a different form. The phrase was in use by 1889. ‘For present uses coagulation and not separation of the race elements in our National melting pot is the thing to be desired,’ wrote the Chicago Tribune that year. ‘The common word “American” is good enough for any of us.’10

The United States was a country, added the New York Times a few months later, ‘in whose mysterious melting-pot all nationalities and races lose their homogeneity and are quickly reduced to the condition of American citizenship’.11 It was six years after Emma Lazarus composed her poem ‘The New Colossus’, which would be mounted on the Statue of Liberty in 1903, inviting the world to send America its tired and poor, its huddled masses and wretched refuse. Within another ten years, the ‘melting pot’ had become a cliché, increasingly used in a pejorative sense: ‘Dregs of Europe … America the Melting Pot into which Races are Poured’, read a typical 1912 headline.12

Over the next twenty years, assimilation and immigration would become incendiary issues, and during the Great War they joined forces with political isolationism under the banner ‘America first’.

* * *

As the war inflamed tensions, even in an ostensibly neutral country, immigrant communities, especially German-Americans, Italian-Americans and Irish-Americans, were being attacked as ‘hyphenates’, whose allegiance to the United States could not be trusted because their divided identities implied divided loyalties. Irish and Italian immigrants were suspected of choosing the Pope over the president, while Jews had long been said to be a ‘nation within a nation’, ‘mercenary minded – money mad’, ‘unmergeable’, ‘alien and unassimilable’.13 The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had sought to ban Chinese immigrants altogether, and before long other Asian immigrant communities would also be directly targeted.

During the First World War, however, it was German-Americans who bore the brunt of xenophobic reaction against ‘hyphenates’. People of German descent were harassed and victimised (in response many anglicised their names, as did the British royal family); the German language became verboten in schools. Even sauerkraut was renamed ‘liberty cabbage’.

Across the United States, this growing animus against ‘hyphenates’ was frequently identified with ‘America first’. The New York Times, for example, argued in 1915 for the virtue of ‘Hazing the Hyphenates’ – which amounted to harassing German-American citizens out of any supposed sympathies they might have felt for Germany in the European conflict. (‘Hazing’ had meant initiation rites that involved tormenting younger students at schools and universities since the nineteenth century.) The Times article began with a recent speech President Wilson had given to the Daughters of the American Revolution, in which he remarked upon a general impression ‘that very large numbers of our fellow-citizens born in other lands have not entertained with sufficient intensity and affection the American ideal’.14

In response to this impression, the president called upon every American ‘to declare himself, where he stands. Is it America first or is it not?’

The Times editorial heartily approved of the president’s demand. No one ‘worthy of his American citizenship’ could possibly object, it pronounced, before endorsing what it called the president’s ‘humorous’ suggestion that hazing was an appropriate cure for any ‘un-American habits’ thus detected. German-Americans may not have seen the humour in a suggestion by the president of the United States that they should be terrorised by their fellow citizens if they failed arbitrary loyalty tests.

‘Probably they will take heed,’ the editorial ended. ‘There is no alternative if they are to continue to live among us, to do business in the United States, to retain their citizenship. Life is hardly worth living under continual “hazing”.’15 Its necessity may have been regrettable, the national paper of record implied, but harassment in the name of ‘America first’ was perfectly justified.

Regional papers also praised Wilson’s remarks. His appeal to ‘pure Americanism’ in this ‘“America first” speech’ went ‘to the mark like a cannon shot’, reported a Kansas paper. ‘One might as well try to obstruct the ocean’s tide as to stand in the way of “America first.” Every new immigrant instinctively knows this.’16

‘Ostracize the hyphen,’ urged a columnist ten days later. ‘Citizens of German birth or parentage are guilty more than any others for this divided allegiance, this half-hearted loyalty, this hindering of the development of simon-pure Americanism.’ (‘Simon-pure’, from the name of a character in a popular play, meant ‘ultra-pure’, the genuine article.) All ‘foreign-born citizens’, he insisted, ‘should take occasion to put themselves on record as cherishing no loyalty to the country of their origin’, and affirm that ‘with them, absolutely and unqualifiedly, it is “America first”’.17

Hyphenate hysteria would not abate any time soon, and it continued to affiliate itself with ‘America first’. In a 1916 editorial called ‘No Room for the Hyphen’, the New York Times was pleased to report that both presidential nominees that year – Woodrow Wilson and his opponent, Republican Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes – had given speeches in which they’d ‘put the hyphen and the hyphenate out of the campaign’. Wilson had again castigated American citizens who had insufficiently absorbed the spirit of America, at least according to their compatriots.

‘We ought to let it be known that nobody who does not put America first can consort with us,’ stated Wilson. Hughes had said something virtually indistinguishable, the Times added: ‘his attitude is one of “undiluted Americanism”’, as purity became the measure of patriotism. Hyphenates were impure, alloyed, defiling true Americanism with their suspicious foreign ways.

‘Anybody who supports me,’ Hughes promised, ‘is supporting an out-and-out American, and an out-and-out American policy.’ The Times out-and-out applauded. The entire East Coast, they warned, would be lost to any party that tried ‘catering to the hyphen vote’. The candidates had both ‘put the hyphen out of American politics. Keep it out.’18

‘Shall we give aid and comfort to the disloyal hyphenate,’ demanded a reader a few months later, ‘to the Germans and their associates?’ President Wilson, wrote the author, ‘stands for America first, but also equally and bravely and nobly for all mankind’.19 All mankind excepting, of course, the disloyal hyphenate, the Germans, and their associates.

In fact, ‘America first’ had become so popular, and so powerful, a political statement in America by 1916 that both presidential candidates adopted it as a campaign slogan. Hughes’s slogan was ‘America First and America Efficient’, while Wilson went simply for ‘America First’.

‘The Administration’s efforts to keep the United States out of war and at the same time maintain the national honor’ was the domestic platform of the Democratic National Convention in the summer of 1916, while its ‘foreign affairs plank will align the party behind the President placing “America first” with reference to all questions, both international and domestic’.20

The promise to put ‘America first’ had several implicit meanings. It meant that they would keep America out of the European conflict, and in the case of Hughes, it meant he would support protectionist trade policies. ‘We commend to every voter,’ wrote the Scranton Republican on election day, ‘the slogan of Charles Evans Hughes, “America First, America Efficient.”’ There was one word, they added, that embodied this slogan more than any other. ‘It is Protection. The protection of American labor and enterprise is imperative to conserve the markets of the United States.’21

A department store in Pennsylvania advertised an ‘All American Sale’, selling goods that were made in America. ‘Be Neutral,’ it urged. ‘America First.’22

‘America first’ also strongly connoted, however, promises to protect ‘real’ Americans from the threat of treachery by ‘hyphenate’ Americans with supposedly divided allegiances. One senator gave a speech in which ‘he deplored the hyphenated American, saying that people in this country could not afford to have two flags’. He criticised any public figures who took the side ‘of aliens when they should be for America first, last and all the time’.23

The North American Review endorsed Hughes’s candidacy in October 1916, stating that Hughes’s ‘entire career confirms’ that he stands ‘for America first’, whereas, ‘disappointingly’, ‘Mr. Wilson stands for Wilson first’.24 ‘“America First, Last and Always And No ‘Hyphens,’” Says Hughes,’ read the headlines in October 1916, after Hughes gave a speech repudiating the vote of anyone who had ‘any interest superior to that of the United States’.25

In his speech, Hughes announced: ‘I am an American, free and clear of all foreign entanglements,’ a deeply coded statement – what today we would call a dog whistle.

Saying that as an individual he had no ‘foreign entanglements’, Hughes was invoking a ubiquitous justification for isolationism, which held that in George Washington’s farewell address of 1796 he had warned America against ‘all foreign entanglements’. It was a frequent and long-standing misquotation; indeed, the phrase is still attributed to Washington, but in fact, those words are not quite what Washington said – and what he really said matters to this history.

Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice?

It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world; so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it; for let me not be understood as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing engagements. I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy. I repeat it, therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But, in my opinion, it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them.

Taking care always to keep ourselves by suitable establishments on a respectable defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies. [emphasis added]

Washington never said ‘avoid all foreign entanglements’, nor does the passage really urge that. The final sentence makes it clear: Washington was not saying that the United States should never enter any alliances at all, but was only warning against permanent alliances in Europe. And he explicitly allowed for ‘temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies’. The First World War could reasonably have been described as an extraordinary emergency, quite apart from the question of whether one statement from 1796 should dictate all of American foreign policy in perpetuity.

But in denying that he himself had any foreign entanglements, Hughes was not raising the possibility that a Supreme Court Justice had colluded with a foreign power. He was, rather, covertly reassuring his audience that he was not a ‘hyphenate’, which meant ‘one hundred per cent American’, which meant a native-born white Protestant.

The idea of ‘one hundred per cent Americanism’, as it was frequently called, itself began as a code for debates about ‘hyphenate’ Americans versus ‘pure’ Americans, before rapidly evolving into ways to suggest – without specifying – other kinds of ‘un-American’ people or behaviour. One suggested slogan for the 1916 Republican campaign, according to the Los Angeles Times, was ‘pure Americanism against the universe’, which is certainly comprehensive.26

‘Pure Americanism’ and ‘one hundred per cent Americanism’ in turn became surreptitious ways to suggest racial and ethnic purity in a society that had long been dominated by the ‘one-drop rule’, which said that one drop of ‘Negro blood’ made a person legally black in the United States. ‘Wherever there was a drop of negro blood in a man he was a negro,’ noted a North Carolina paper in 1903. ‘It took one hundred per cent of Anglo-Saxon blood to make a white man, but one per cent of negro blood makes a black man.’27

The ‘one-drop rule’ was the foundation of slavery and miscegenation laws in many states, literally used to determine the legal status of individuals, whether they would be enslaved or free. Its logic extended from the notorious three-fifths compromise in the Constitution, which computed slaves as three-fifths of a person for purposes of counting the population when apportioning representation to government. Slaves could not, of course, vote; but white slave owners wanted them to count as part of the population so that their states could send more representatives to government, surely one of the more outrageous instances of having it both ways in human history. America was a nation long accustomed to quantifying people in terms of ethnic and racial composition, as words like mulatto and half-caste, quadroon and octoroon, make clear.

Declaring someone ‘one hundred per cent American’ was no mere metaphor in a country that measured people in percentages and fractions, in order to deny some of them full humanity.

The associative chains ran along the eugenicist idea of racial purity, and all these phrases began to suggest each other. It was all too easy to conflate ‘pure American’, ‘one hundred per cent American’ and ‘one hundred per cent Anglo-Saxon’, and many Americans in the first decades of the twentieth century were eager to do so.

‘Our great American melting pot,’ stated a 1917 Arizona editorial, ‘contains a mixture that boils, fumes, bubbles, steams. In the semi-solution are held all sorts of elements. Some observers are pessimistic concerning the possibilities of a perfect blend,’ it added, while others believed ‘that the crisis [of war] had proved a magic element to precipitate the foaming mixture into clear, hard, shining crystals of pure Americanism’. Sadly, even the catalyst of war was insufficiently magical to create a crystalline Americanism. ‘We still have in our midst men who love Germany more than they love American liberty.’28

Charles Evans Hughes was congratulated for demanding ‘an Americanism that is “100 per cent pure”,’ one that ‘leaves no room for any hyphenated constituent element. Only “an undivided, unwavering loyalty to our country,” only “a whole-hearted, patriotic devotion, overriding all racial differences” will be tolerated.’29 Pure Americanism rejected hyphenate elements, but patriotic devotion was meant to override racial differences: the logic became self-cancelling, but that didn’t stop anyone from deploying it.

Anyone who was less than one hundred per cent American could thus, by the long-standing logic of the one-drop rule, be rejected as non-white, non-American, or both. Nativism – combining racism, xenophobia and inherited position – created a syllogism, in which ‘one hundred per cent’ denoted both pure white and pure ‘American’, which became rhetorically interchangeable.

Within six months of Wilson’s ‘America first’ speech, the association was clear enough that a self-styled ‘Southern Democrat’ in Kansas was announcing that the ‘next big national issue will be America for pure Americans’. The ‘main issue’, he stated, ‘has already been defined by President Wilson in two words, “America First”’, which meant that the United States must determine ‘whether in its national aspirations, ideals and sympathies it is to be all American or half alien’.30

Soon it became impossible to disentangle the codes – which is one of the points of deploying them. Codes create plausible deniability, and not merely in public. They can also give people who use them a way to evade their own cognitive dissonances. The codes are there to muddy the waters, to keep people from seeing their own faces in the pool.

Perhaps the most prominent advocate of ‘America first’ isolationism was the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, who supported Hughes’s candidacy. Hearst’s editorials were reprinted throughout the country, urging America to put ‘America first’ and steer clear of ‘entangling alliances’, another popular mangling of Washington’s words.

The Hearst syndicate’s ‘great anxiety for “America first”’ was frequently remarked. ‘In big black type, Hearst has said repeatedly “America first.”’31 ‘“America first!” was the text of his campaign’, a constant refrain in the American papers to keep the country out of the war.32 Tiny local papers like the Hardin County Ledger in Iowa reprinted Hearst’s editorials in their entirety, in which he argued for months: ‘We should inflexibly resolve to keep out of entangling alliances, to fight our own war in our own way; to use American money and American men only for the defense of America.’33

Being free of ‘foreign entanglements’ was thus another way of conflating ‘anti-hyphenate’ xenophobia and nativism with isolationism and ‘America first’. They were all knotted up – because it’s not as easy to steer clear of all entanglements as some would like to believe.

Woodrow Wilson always tried to differentiate his use of ‘America first’ from isolationism, insisting the slogan was actually internationalist, meaning America should take the lead. ‘AMERICA FIRST is a slogan which does not belong to any one political party,’ he later said. For the Democrats, as opposed to the isolationist Republicans, it meant, he insisted, that ‘in every organization for the benefit of mankind America must lead the world by imparting to other peoples her own ideals of Justice and Peace’.34

It was a neat ploy, worthy of the wily old diplomat; but Wilson’s other 1916 slogan for re-election was balder: ‘He Kept Us Out of the War.’

* * *

As an expression ‘one hundred per cent American’ is often attributed to a 1918 speech Theodore Roosevelt gave called ‘Speed up the War’, in which he declared: ‘There can be no fifty-fifty Americanism in this country. There is room here for only 100 per cent. Americanism, only for those who are Americans and nothing else. We must have loyalty to only one flag, the American flag.’35

But the phrase was in circulation by at least 1915, when a rabbi urged his synagogue to follow ‘Ten Commandments of True Americanism’, instructing them: ‘True Americanism means 100 per cent. Americanism.’36 And in a 1916 letter that was reprinted in the New York Times and then around the country, Charles Evans Hughes thanked Roosevelt for endorsing his candidacy. ‘No one is more sensible than I of the lasting indebtedness of the nation to you for the quickening of the national spirit, for the demand of an out-and-out – 100 per cent – Americanism.’37

During his post-presidency in fact Theodore Roosevelt gave many speeches about ‘100 per cent Americanism’ and ‘hyphenates’, including ‘America for Americans’ in 1916, in which he also tended consistently to add that the question was strictly one of loyalty to the United States, not of a person’s ethnic origins. He routinely mentioned his own Dutch heritage, while promising he would personally vote for president ‘any American of German, Irish, Scandinavian or other parentage, of whatever creed’. It was ‘a violation of every principle of true Americanism to discriminate’ against anyone because of their heritage.38 But these qualifications were rapidly lost in translation (and it’s worth noting that he only named Northern Europeans).39

Before long, America first, one hundred per cent American, pure American and patriotism were being used more or less interchangeably. A nationally syndicated Baltimore Star editorial in 1918 described a local man as ‘a one-hundred per cent patriot, [and] not only one-hundred per cent American – for there are, it is to be regretted, many one-hundred per cent Americans who are not even fifty per cent patriots’.40

What is being measured in thus sifting Americanism? Not patriotism, for if it were, there would not be a distinction between fifty per cent patriots and one hundred per cent Americans. It had to connote ‘real American’, which almost certainly translated into white and native-born. ‘All willing to pledge full one hundred per cent allegiance to our government, and then give it, should alone be entitled to the honored name of “American citizen”,’ stated a South Dakota editorial in July 1918.41 Similarly, in a widely circulated article titled ‘Confessions of a Hyphenate’, a recent immigrant explained that nothing he did was sufficient to earn him the label ‘One Hundred Per Cent American’. ‘Three years ago I believed that I was a full-fledged American, as indistinguishably merged in the stream of American life as one drop of clear water merges with another. I should have known better,’ he wrote in The Century. ‘The immigrant can no more turn himself into a one hundred per cent American than the rabbit can grow a mane. Whether he be a Pole in Germany, a Chinaman in Japan, an Italian in the Argentine, or a German in America,’ he concluded bitterly, ‘the immigrant must always remain a citizen of the second class.’42

When Congressman Julius Kahn of California (‘perhaps the leading Jew in American public life’)43 announced, ‘I am an American, for America first, last and all the time; no other country appeals to me,’ the San Francisco Chronicle put this declaration under the subheading ‘100 Per Cent American’, although Kahn never used that phrase. The expressions had become synonymous enough for an editor to treat them as interchangeable.44

It is therefore also likely the case that when the Chronicle declared above its masthead from 1918 to 1920, ‘This Newspaper is One Hundred Per Cent American’, it was sending a dog whistle to all its readers that it was for ‘America first’, and for ‘pure Americans’, as well as signalling political isolationism.

In fact, the more you pull on the threads that knot ‘America first’ and ‘one hundred per cent American’ together, the more you find other strands pulling the knot tighter.

Julius Kahn was himself a German-born immigrant – a ‘hyphenate’ – who was elected to Congress in 1899. Soon he had co-authored the Kahn–Mitchell Chinese Exclusion Act of 1902, a law making the Chinese Exclusion Act permanent. (In other words, a German Jew could, with hard work, good fortune and a willingness to exclude other minorities, be accepted into the one hundred per cent club. The Chinese, however, were out of luck.)

Another immigrant congressman was proclaimed one hundred per cent American not long after Senator Kahn was – and this case is equally instructive. When Senator Knute Nelson died, he was hailed in obituaries across the land as ‘one hundred per cent American’ – despite having been born in Norway.

Nelson got a free pass to pure Americanness because (as his obituary helpfully spelled out) he was descended from ‘the true Nordic line’, ‘from the race which set up strong gods and bred strong men’. Like the list of hyphenates Teddy Roosevelt was prepared to accept as true Americans, Nelson came from the right part of Europe, the northern part. His years of public service could thus demonstrate ‘the value to America of men born over the seas who become Americans in the fullest meaning of that phrase which distinguishes the best among us: “He was a one-hundred-per-cent American.”’45

The reason why being Nordic made Nelson one hundred per cent American (which might seem oxymoronic) was that ‘Nordic’ and ‘one hundred per cent American’ were also intertwined. As if all of this weren’t confused enough, ‘Nordic’ was yet another code, used in the first decades of the twentieth century in the same ways that the Nazis would use ‘Aryan’.

‘Nordicism’ held that people of Northern Europe were biologically superior to those of Southern Europe, a theory espoused by white supremacists like Madison Grant, whose 1916 The Passing of the Great Race: or The Racial Basis of European History became one of the most influential works of eugenicist scientific racism. ‘The Nordics,’ Grant wrote,

are, all over the world, a race of soldiers, sailors, adventurers, and explorers, but above all, of rulers, organizers, and aristocrats in sharp contrast to the essentially peasant character of the Alpines. Chivalry and knighthood, and their still surviving but greatly impaired counterparts, are peculiarly Nordic traits, and feudalism, class distinctions, and race pride among Europeans are traceable for the most part to the north.46

Grant warned of the imminent ‘great danger’ in America of ‘replacement of a higher type by a lower type’, unless the ‘native American’ (i.e. nativist, white descendants of early European settlers) ‘uses his superior intelligence to protect himself and his children from competition with intrusive peoples drained from the lowest races of eastern Europe and western Asia’.47 Grant’s proposed solutions to this impending crisis including the building of ghettos and the sterilisation of ‘inferior’ humans.

But in practice, ‘Nordic’ was used to describe anyone who was blonde, or white, or ‘Caucasian’, or ‘Anglo-Saxon’, or Northern European, as well as anyone who was actually from Norway. (This could lead to entertaining mix-ups, when racists got confused about who they hated, as we shall see.)

None of it was pretty, and none of it was lost on contemporary observers – nor was it intended to be, as a North Carolina woman made clear in a letter to her local paper in 1920. ‘I do not relish all this “One hundred per cent. American,” “America first” propaganda to the exclusion of other nations, not because I am not a loyal American, but because I am.’48

But many Americans embraced it. A Colorado rancher whose son had been killed in action told an audience in the Midwest: ‘You folks do not seem to take this war seriously enough. With us out west it is a matter of life and death. We have our One Hundred Per Cent American societies, and I want to tell you that any disloyal utterances or actions will result in a necktie party with a rope, a tree and a Hun the principal factors.’49

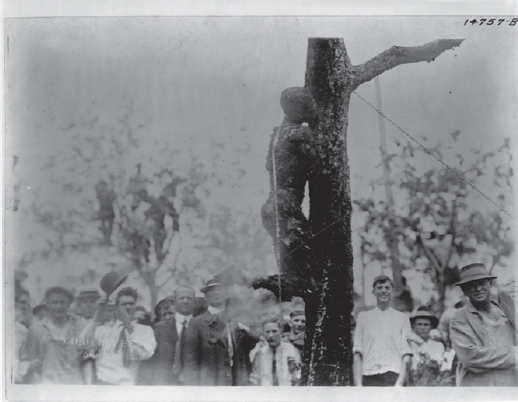

Patriotism, citizenship, ethnic purity and racial purity were all being conflated: it was a short rhetorical step from ‘One Hundred Per Cent American societies’ to lynching, because of the associative chains that had been created. Loaded phrases slamming into each other with sufficient force could detonate into real violence; slogans are not mere words when they create political realities.

That this was no idle threat was made all too brutally clear a month after the Colorado rancher threatened to lynch any German he deemed insufficiently loyal – when a Midwestern mob did just that. ‘Mob May Have Made a Fearful Mistake,’ admitted a Florida headline in 1918, reporting the story of a ‘socialist lynched’ in Illinois for ‘disloyal utterances’. The victim prayed in German before being ‘strung up’; his killers subsequently found in the dead man’s pockets a statement of loyalty to the United States.50

Threats of lynching were directed with some frequency against hyphenates. And although the term ‘hyphenate’ was most often applied to immigrants, it would have also implicitly conjured for many listeners the hyphenate term ‘African-American’, a phrase used by abolitionist newspapers as early as 1835.51 By 1855, an abolitionist was distinguishing ‘African Americans’ from ‘Saxon Americans’.52 ‘The two greatest questions which, in the progression of the age, cannot be escaped, were the Anglo-American and the African-American,’ said another in 1859.53

Fifty years later, avowed hostility towards ‘hyphenate’ identities did not have to explicitly name African-Americans to implicitly differentiate them from ‘Anglo-Americans’ or ‘Saxon Americans’. Nor should this be a surprise: race and immigration have been intertwined in America since at least the antebellum days of Know Nothing nativism in the 1850s, when the ‘Native American Party’ formed from the remnants of the Whigs to oppose the influx of European immigrants fleeing revolution and famine, but equally to oppose the abolitionist policies of the nascent Republicans, whom Lincoln would soon lead.

By the early years of the twentieth century, as with ‘America first’, so the animus against all ‘hyphenates’ had become something that many Republicans and Democrats could agree on.

* * *

Although seven presidents lobbied against lynching, Woodrow Wilson was not one of them; under pressure, he gave just one speech denouncing it. Nor would he likely have been made uneasy by the increasing associations of his campaign slogan with eugenicist ideas of racial purity. Wilson’s speeches against hyphenates were no mere campaign tactic. Although an internationalist whose administration passed progressive legislation including the Federal Reserve Act, Wilson was reactionary in matters of race. In fact, Wilson was one of the many white supremacists who have inhabited the White House, going right back to the ones who had slaves build it for them.

A native Virginian born nine years before the Civil War began, Wilson came of age with the national romance known as the Lost Cause. In the aftermath of the South’s crushing defeat in the Civil War, Southerners began trying to reclaim what they had lost – namely, an old social order of unquestioned racial and economic hegemony. They told stories idealising the nobility of their cause against the so-called ‘War of Northern Aggression’, in which Northerners invaded the peaceful South out of a combination of greed, arrogance, ignorance and spite. Gentle Southerners heroically rallied to protect their way of life, with loyal slaves cheering them all the way. This Edenic myth of a lost agrarian paradise, in which virtuous aristocrats and hard-working farmers coexisted peacefully with devoted slaves, predated the war: merging with Jeffersonian ideals of the yeoman farmer, it formed the earliest propagandistic defence of slavery.

Since the Civil War, the Democrats were the party of the South, opposed to Lincoln’s Republicans, the party of the North and Union, over the question of slavery and civil rights (itself a phrase associated with the rights of African-Americans as far back as antebellum abolition arguments). After the war the party of Lincoln gradually evolved into the party of urban industrialism, while the Democrats were firmly aligned until the 1940s with Southern agrarianism. And because of this ideological allegiance to Southern agrarianism, the Democrats were also the party of states’ rights, Jim Crow segregation and white supremacism.

Although Woodrow Wilson was not a typical ‘Southern Democrat’ – he had been governor of New Jersey, and was elected in 1912 as a progressive – his views were not always distinct from theirs. As president, Wilson instituted segregation in the federal government, including separate toilets in the US Treasury and Interior Department. His Treasury Secretary, who then became his son-in-law, William G. McAdoo (born in Georgia in 1863, in the midst of the Civil War), defended the decision by arguing that it was ‘difficult to disregard certain feelings and sentiments of white people in a matter of this sort’. Luckily for them, it was easy to disregard the feelings and sentiments of black people.

A delegation from the National Independence Equal Rights League came to the White House in 1914 to express their dismay at federalising segregation. Wilson insisted that it was ‘enforced for the comfort and the best interests of both races in order to overcome friction’. Told that his support for segregation would likely result in the united opposition of African-American voters in the 1916 election, Wilson took umbrage, ‘saying that if the colored people had made a mistake in voting for him they ought to correct it, but that he would insist that politics should not be brought into the question because it was not a political problem’, but ‘a human problem’. The delegation left, informing reporters that Wilson’s ‘statement that segregation was intended to prevent racial friction is not supported by the facts’.54

In 1915 Wilson became the first president to show a movie in the White House: The Birth of a Nation, directed by D. W. Griffith, who was himself the son of a Confederate colonel. The now notoriously racist film was based on an even more racist novel called The Clansman, by Thomas W. Dixon – with whom Woodrow Wilson had become acquainted at Johns Hopkins University. Dixon was himself a staunch upholder of the one-drop rule, as he had explained to a local reporter in North Carolina. ‘There is no reconciling the essential difference between the negro and the Anglo-Saxon,’ Dixon announced, because ‘one drop of negro blood makes a negro’.55 Dixon wrote a series of books mythologising the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, part of the ‘moonlight and magnolia’ school of plantation fiction, of which another member was the writer Thomas Nelson Page – whom Woodrow Wilson appointed his ambassador to Italy.

Nelson’s novels, such as In Ole Virginia (1887) and Red Rock (1898), helped establish the formula: devoted former slaves recount (in dialect) their memories of a halcyon plantation culture wantonly destroyed by militant Northern abolitionists and power-crazed federalists. A small band of honourable soldiers fought bravely on the battlefield and lost; the vindictive North installed incompetent or corrupt black people to subjugate the innocent whites; Southern scalawags and Northern carpetbaggers descended to exploit the battle-ravaged towns. Pushed to the limits of forbearance, the Confederate army rose again to defend honour and decency – in the noble form of the Ku Klux Klan. It was a pernicious fiction turning the armed defence of institutional slavery into a beau geste.

The Birth of a Nation outlines this myth in fulsome, false detail, telling a story in which ‘the former enemies of North and South are united again in common defense of their Aryan birthright’, as an intertitle declared. Dixon reportedly said that his purpose ‘was to revolutionize Northern audiences’, writing a story ‘that would transform every man into a Southern partisan for life’, while Griffith said that one of his hopes for the film was that it would ‘create a feeling of abhorrence in white people, especially white women, against colored men’.56

It worked. The Birth of a Nation was a national phenomenon. Northern white audiences cheered; black audiences were horrified. The film prompted riots and racist vigilante mobs in cities across America, as well as at least one homicide, when a white man killed a black teenager – in Indiana, not in the Deep South.

The Birth of a Nation was single-handedly responsible for rekindling interest in the Ku Klux Klan, resuscitated by ‘Colonel’ William Joseph Simmons after viewing The Birth of a Nation and its depiction of Klansmen as heroes. Before long, slogans like Wilson’s ‘America First’ and Roosevelt’s ‘100 per cent Americanism’ would give the resurgent Klan its own codes.

For all the Klan’s divisiveness, its extension across the country also worked perversely to reconcile North and South just as The Birth of a Nation imagined, as ‘Anglo-Saxons’ united against perceived threats from groups they sought to subordinate; the election of the Southern segregationist Wilson functioned in the same way, helping to reunite the nation in the wake of Reconstruction.

And in the meantime, even without the help of the Klan, white people had continued to brutalise black people across the country. Between 1889 and 1922, according to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), 3,436 people were lynched in America – and that’s just the official records.57 No one knows how many more victims went unidentified, and unaccounted for. Although the vast majority of victims were African-American, Catholics and Jews were also lynched, as were women. The Mexican government sued the United States for failing to prosecute those responsible for the lynching of Mexican nationals; Italian nationals were lynched as well, including eleven suspected of a murder in 1891.

Lynching was not always, or even primarily, a furtive outbreak of violence in the dead of night. By the turn of the century, in many parts of America lynching had turned into entertainment, a blood sport. Public lynchings took place in the cold light of day, with plenty of advance warning, so people could travel from outlying areas for the fun. There were flyers and notices letting spectators know when and where the lynching would take place; local newspapers ran headlines announcing impending plans; reporters were sent to cover it; families brought children, and had picnics. Victims were frequently tortured and mutilated first; pregnant women were burned to death in front of a peanut-crunching crowd.

A Jewish man named Leo Frank was lynched in Georgia in October 1915, scapegoated for the death of thirteen-year-old Mary Phagan. Two months later, ‘Colonel’ Simmons lit his vicious fire on Stone Mountain, Georgia, and proclaimed the Ku Klux Klan reborn.

In Texas in May 1916, a black farm worker named Jesse Washington, accused of murdering the white woman he worked for, was lynched in front of the Waco city hall. Washington was not hanged. First he was castrated, then his fingers were cut off, then he was raised and lowered over a bonfire for two hours, until he finally died. His charred body was then dismembered, the torso dragged through the streets, and other parts of his body sold as souvenirs.

It happened in broad daylight, in the middle of the day, as some 10,000 spectators watched, including local officials, police officers and children on their school lunch break. Photographs were taken of Washington’s carbonised body hanging above grinning white people and turned into postcards.

That’s the reality of what being ‘one hundred per cent American’ and for ‘America first’ meant to a great many citizens of the United States in the first decades of the twentieth century.