Like the ‘American dream’, ‘America first’ rapidly narrowed its meanings when the United States entered the First World War. Wartime patriotism made the phrase incompatible with isolationism; for the next two years it became more or less pure jingoism, with frequent comparisons to other nationalist slogans such as ‘Vive la France!’ and ‘Rule Britannia’ – while loudly deriding ‘Deutschland über Alles’ as repugnantly militaristic.

The hypocrisy in this position was frequently pointed out. ‘The very people who are most insistent that “Deutschland ueber alles” is the device on the devil’s banner are the people who are yowling most tremendously in favor of everybody’s slogan of “America First”,’ observed a North Carolina editorial. But there was nothing to choose between militarist slogans in their implicit belligerence and nationalism. If ‘America first’ became the country’s guiding principle, the editorial warned, it would inevitably lead the nation towards further conflict. ‘We have faith to believe that this country is not, and never has been, for “America first”,’ it concluded. ‘We hope and believe that it is for Justice first.’1

But such hopes were increasingly belied by the degree to which American xenophobia was now militarised and fully legitimated, with its own campaign slogan. It inspired some truly dreadful poetry:

And a great deal of equally silly fiction. In September 1917 Hearst’s Magazine ran a story called ‘The Pawn’s Count’, featuring a German-American, ‘a Japanese’, ‘the villain, Mohammedan Hassan’, and the heroine, ‘Cammella Van Peyl’, who despite her exotic name is ‘the American girl “for America first, only, always”.’

‘You cannot frighten me, Hassan,’ America-first Cammella announced in an illustrated advertisement that helpfully glossed her words (‘Yankee girl hard to frighten’), amidst its casual anti-Muslim stereotyping.3

The wartime patriotism that swept America in 1917 and 1918 was not restricted to invocations of the American dream or America first, of course. The ‘American creed’ also made a comeback, courtesy of a descendant of President John Tyler named William Tyler Page, who won $1,000 in a ‘national citizen’s creed contest’. Page’s American creed begins:

I believe in the United States of America as a government of the people, by the people, for the people, whose just powers are derived from the consent of the governed; a democracy in a republic and a sovereign nation of many sovereign States; a perfect Union, one and inseparable; established upon those principles of freedom, equality, justice and humanity for which American patriots sacrificed their lives and fortunes.4

Page’s creed was recited in schools and town halls across America for the next several decades, inculcated into tens of thousands of American citizens. Like the pledge of allegiance, which was composed in 1892 and popularly recited for decades before it was made official in 1945, so would Page’s American creed return in the fight against totalitarianism.

* * *

When the First World War ended, ‘America first’ quickly shifted its meaning back from wartime jingoism to pure isolationism. No contradiction registered, for its nationalism remained consistent.

Wilsonian attempts at characterising ‘America first’ as a slogan for American world leadership were overpowered by a wave of popular resistance to any further entangling alliances. The country’s sentiment had not broadly changed; a majority of the population still felt that Europe’s problems were its own, and that the US government should focus its energy domestically. They had made an exception for the Great War; that exception was over and it was time to return to the isolationist norm.

In particular, Wilson’s position on the Treaty of Versailles and his advocacy of the League of Nations was not popular at home. Progressives objected to its harsh reparations and the huge debt burden it imposed on Germany, as well as to its arbitrary disposition of territories, viewing these as a betrayal of the principles of justice for which they had fought. Conservatives despised Wilson’s attempts to establish the League of Nations, seeing it as a nightmare of permanent entangling alliances – and this time Washington’s farewell address was more accurately cited.

Congress was baulking especially at Article X, which allowed for collective action to maintain peace, enjoining all member nations to ‘respect and preserve … against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing independence of all Members of the League’. This was anathema to non-interventionists certain it cloaked imperialist tendencies and was a pretext for enforcing the will of the imperial League. Its opponents argued that Article X bound the United States to a permanent, global commitment to send troops to any place, at any time, if the League detected ‘external aggression’.

America first had backfired against Wilson: now it was leading his opponents to call his desire to join the League of Nations ‘indefensible’.

One of the problems with Article X was the widespread view, shared by progressives like Walter Lippmann, that the post-war settlement of territories was unjust, and it would force America to defend that injustice. Lippmann predicted it would lead to ‘endless trouble for Europe’, warning, all too accurately, that the Versailles Treaty would surely prove ‘a prelude to quarrels in a deeply divided and hideously embittered Europe’.5

But others were opposed to the League of Nations for the way it seemed to transfer democratic agency away from individual citizens, and towards cabbalistic foreign powers and international financiers. Many white male owners of small farms and businesses, in particular, saw in the League of Nations yet another encroachment on their political hegemony, yet another incremental degree of influence transferred away from them and towards ‘alien’ groups, diluting the concentration of their power.

As American politicians and press called for protectionist tariffs, they began debating the question of what they called ‘economic nationalism’, another phrase that would be revived a century later. Bankers argued that the US must ‘meet and compete with the economic nationalism of other peoples’.6 A widely reprinted New Republic leader countered that the establishment’s opposition to German democratic autonomy was clearly a pretext for creating what would later be called the military-industrial complex, ‘a future structure of armament, militarism, economic nationalism, and power politics’ in America.7

‘America first’ was soon taken up as a rallying cry for protectionist tariffs and against the League of Nations. Citizens wrote in to the papers explaining why Republicans were the most patriotic party. ‘The Republican party may rightly be called the American party,’ claimed a letter to the New York Tribune. ‘Let our motto be America First.’8

William Randolph Hearst was the nation’s most relentless opponent of Article X. For Hearst, the League of Nations and Article X would inevitably entangle America in foreign conflicts in Europe, and he led the domestic campaign against Wilson’s efforts to persuade Congress to sign the Treaty, reiterating that the League of Nations and the World Court were ‘loathsome’ organisations, whose sole purpose was to enmesh the United States in foreign conflicts that could destroy it.

In editorials and letters to the press, Hearst openly threatened politicians who supported the Treaty. Surely any patriotic statesman, Hearst ruminated in one, would want American citizens ‘to know how he voted and to REMEMBER how he voted’. Hearst was prepared to use his publications – ‘read now by twenty-five million Americans and increasing daily in the number of their clientele’ – to ‘keep those statesmen and their votes for as many years as may be necessary before the American people’.

If, in the end, the Treaty was accepted by Congress, Hearst vowed to ‘consecrate’ his publications ‘to the formation of a new party … whose dominating idea will be “America First,” and whose sole devotion will be to the Liberty, Democracy and INDEPENDENCE which have made America first of all nations of the world’.9

The Scranton Republican warned readers that internationalism, with ‘its subtle illusions’, ‘its glittering generalities and its appeal to universal sentiment’, was deluding American citizens. ‘The people of this country must not lose sight of the fact that a principle to which they must tenaciously adhere is “America first.”’10

Fears of international propaganda infiltrating America were not assuaged by reports like the one revealing a ‘Fake News Bureau in Europe’, a plan ‘whereby news without foundation, or entirely distorted, is given out for transmission to America for purely speculative purposes’.11 Propaganda was itself a new and worrying idea, exposing for the first time how easy it was to use false or distorted information to manipulate opinion.

Concerns about propaganda had emerged during the war; the threats that systematic propaganda posed to democracy were instantly apparent, as the fragility of any system depending on the wisdom of crowds became all too clear. Modern ideas about advertising showed that political slogans could help create a campaign brand, persuading voters to choose not only a candidate but a political position. Where in the nineteenth century name recognition was often sufficient (think ‘Tippecanoe and Tyler, too’), in the twentieth century, candidates increasingly aligned themselves with ideologies – like ‘America first’.

‘America first’ and associated ideas of Americanisation, including calls for English as a national language, were touted as antidotes to foreign propaganda and alien ideas. ‘America first must be stamped upon every heart. There should be but one language in the public grade schools – the language of the Declaration of Independence, of Abraham Lincoln, of Theodore Roosevelt,’ pronounced General Leonard Wood, who had commanded Roosevelt’s rough riders and was seeking the Republican nomination in 1920. ‘Avoid loose-fibred internationalism as you would death, for it means national death.’12

Despite these efforts to claim ‘America first’ as an improving ideal, many leading educators publicly despised it. Charles W. Eliot, former president of Harvard, wrote to the New York Times in withering terms:

America first: this is the lowest estimate of the intelligence and good sense of the American people that has ever been made by native or foreigner. That such an estimate should be made by public men who had the means of watching the way the minds and hearts of the common and uncommon people in the United States worked in 1917 and 1918 would seem incredible, but is a humiliating fact.13

More representatively, Republican Senator Walter Edge of New Jersey announced that there was ‘a distinct difference between an “America first” citizen’, and those seeking a dream of ‘world power’ that would ‘engulf’ the United States ‘in the maelstrom of Europe without qualification’.14 Editorials around the country agreed, criticising Wilson’s ‘tenacious adherence’ to an ideal of international brotherhood for which ‘the world is not yet prepared’.15 ‘In brief, Americans want to safeguard America first.’16

Before long, ‘America First, Last and All the Time’ had been resuscitated around the country. Local papers from Wilmington, Delaware, to Green Bay, Wisconsin, adopted it as their motto, printing it on the editorial page of every issue.

By early 1920, Hearst’s New York American – declaring that its ‘inspiration is “America First”’ – was offering a $500 prize, and one hundred ‘“America First” Silver Medals’, for the best student essay written in celebration of George Washington, who ‘was for AMERICA FIRST, LAST AND ALL THE TIME’.17 Off and on for the next two decades, Hearst would add ‘America First’ to the mastheads of his newspapers from coast to coast.

On 19 March 1920, the Senate refused for a second time to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, sending it back to President Wilson (about whose stroke six months earlier rumours were finally beginning to circulate). The next day, the New York Times shared outraged letters from American citizens insisting that the country should take a leading role in the peace process, trying to reclaim the old Wilsonian internationalist meaning of ‘America first’ as first to do right in the world.

‘With indignation and shame we behold America fallen from her position of leadership among the nations,’ one attested. ‘“America First” ought to mean America first (not last, as now), to redeem her pledge; America first, not last, to pay her debt of honor; America first, not last, to make a willing sacrifice.’18

In the summer of 1920, Republicans nominated Warren G. Harding, who had successfully campaigned for the Senate back in 1914 on a platform of ‘Prosper America First’. Now Harding adopted it as his presidential campaign slogan. ‘Call it the selfishness of nationality if you will, I think it an inspiration to patriotic devotion – To safeguard America first, to stabilize America first, to prosper America first, to think of America first, to exalt America first, to live for and revere America first.’19

Many Americans did indeed call it the selfishness of nationality. A North Carolina paper reported that Harding was being denounced as ‘an exponent of “the reactionary, mediaeval creed of selfish, egotistic, jingoistic nationalism”’.20 Jingoism, the Indianapolis Journal had told its readers back in 1895, was a British term for those who seek power ‘by browbeating and crowding other nations with threat of war’. Jingoism was patriotism for bullies; it picked on weaker nations, and never spoke of principle, only of glory; never of justice, only of self-interest.21

That summer, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge delivered a keynote speech at the Republican National Convention, denouncing the League of Nations in the name of ‘America first’. The American people would never accept the Treaty of Versailles, Lodge warned, declaring that ‘no man who thinks of America first need fear the answer’ to Wilson’s ‘imperious demand’.22

By 30 June Harding had recorded ‘America first’ on a new device called a phonograph as part of the campaign; a month later he cited it in accepting his nomination, promising to use ‘America first’ to oppose ‘the supreme blunder’ of Wilsonian internationalism and the League of Nations. Others noted the irony. ‘Candidate Harding is making a great to do about “America first.” The trouble with that slogan in Republican mouths is that it is borrowed from the Wilson Administration.’23 So, on the face of it, was Harding’s campaign poster, which was markedly similar to Wilson’s of four years earlier.

The American Economist endorsed Harding’s candidacy in a leader reprinted around the country, promising that Harding (‘a clean man of upstanding character’) would usher in ‘an era of nationalism, instead of internationalism, that we shall have as the Head of the Nation a man who thinks for “America First”’.24

Not everyone was convinced. A North Carolina editorial objected: ‘Senator Harding prates about “America first.” Who wants to put America second? Had it not been for the Republican Senators in Washington, among whom Senator Harding is one, America would today really be first, sitting at the head of the table in the great concert of powers for the preservation of the peace and liberty of the world.’25

But for many Americans, the motto quickly came to seem axiomatically patriotic. An ad was taken out in Texas for Independence Day: ‘Tomorrow – July 4th – the American people will again renew their allegiance to the greatest of all flags, and will again avow their faith in the great principles embodied in the Declaration of Independence. America First has become the slogan of all loyal Americans.’26

This paean to civic virtue was slightly undermined by the fact that it was selling a laundry service (‘Long Live your Linen – Long Live Your Clothes’) in which Uncle Sam was pictured pensively mulling ‘America First’.

Whatever the ad’s unintentional comedy, the point is that ‘America first’ had become so fully absorbed into the national conversation that by 1920 it seemed to many Americans as iconic as the Fourth of July, the Declaration of Independence and Uncle Sam.

* * *

But it also remained divisive. Americans all over the country wrote to their local papers and to the New York Times, repudiating the expression and its sentiments, seeing in them, as others had done, an ugly ultra-nationalism. ‘When [Harding] closed his first home-coming speech with “America first” six times reiterated, one felt that surely he would have something like “Deutschland über Alles” to say,’ one correspondent observed.27

Another announced more baldly: ‘“America first” seems to me a mighty mean slogan.’28

The Pittsburgh Post censured Harding in July for implying that those who disagreed with him were not putting ‘America first’. Americanism, the editorial argued, should not be judged only by love of country during war, but ‘also by loyalty to its principles in peace. If there is one principle that stands out more than another in the American creed for all times it is tolerance of opinion. It follows that an intolerant man is far from being an ideal American.’29

But Harding was routinely impugning the integrity of those who disagreed with him, including progressives in his own party who dared to challenge the Republican old guard. Now, the leader added, he was attacking his political opponents by despicably claiming ‘that Democrats are not for America first’. The sooner Harding realised it was beneath contempt to accuse his opponents of being traitors just because they disagreed with him, the better it would be for everyone.30

The New York Times did the Post one better. It dismissed ‘America first’ as itself beneath contempt, roundly mocking the ‘banality’ of the phrase, ‘the greatest volume of commonplace ever uttered. “America first!” “Aye, my countrymen, let us all love our native land.” Thrilling cries like these have been dinned into all ears from every Republican stump.’ The best thing about Harding’s speeches, the editorial concluded, was that they furnished ‘such complete intellectual relief’ for anyone with a brain.31

The motto continued to play well to crowds, however, and specifically to the xenophobic fears that politicians were busily stoking. That autumn, in what became known as his ‘Address to the Foreign Born’, Harding offered ‘America first’ as an antidote to the dangers of ‘hyphenate Americans’. Declaring himself ‘unalterably against any present or future hyphenated Americanism’, Harding warned that the League of Nations would only ‘drive into groups’ Americans ‘whose hearts are led away from “America First!” to “Hyphen First!”’

America must guard against an ‘organized hyphenated vote’, Harding maintained, so as to avoid having control over the nation ‘transferred to a foreign capital abroad’.32 All of these euphemisms – internationalism would drive voters into groups, the nation must block an organised hyphen vote, there were foreign cabals waiting to grab American wealth – amounted in real terms to the demonisation of any immigrant communities voting as a bloc, internationalism deliberately conflated with xenophobia.

Criticising the Democrats for failing to make a positive case for their own values, Harding pronounced: ‘We do not know what our opponents stand for. I stand for a united America, a humane America, an efficient America, America first.’33

The subtexts of these coded phrases were not lost on Harding’s audience. ‘The slogans “America first” and “I am in favor of staying out” bring a chill,’ wrote one angry citizen just before the election, on 31 October 1920. ‘America may “stay out” of the League, but she will not “stay out” of history.’34

In October, Will Hays, chairman of the National Republican Committee, had proclaimed that he could see ‘Republicans “Marching to Victory” Under “America First” Banner’.35 On 3 November, they did just that, sweeping the White House and Congress against a Democratic ticket that included a vice-presidential nominee named Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

After Harding’s victory, he stated that the Great War had been fought not to secure democracy, but to secure American rights abroad: internationalism would only be in the service of nationalism. European politicians, worried about America withdrawing from the world stage, assured each other that ‘while Senator Harding’s success is momentarily a victory of the ideas represented by the slogan “America First”’, it did not mean that the United States would hold that line for long.36 Surely it was just a campaign tactic, and America would return to a position of world leadership.

Once Harding won, for many Americans the phrase seemed legitimised; soon it was viewed as an administrative policy, rather than merely a slogan. A letter to the New York Times just after the 1920 election defended the idea: ‘“America first,” as every well-informed person understands, simply means the protection and defense of our own domestic affairs at home against the invasion or interference of any unfavorable outside influences,’ including ‘the discussion or practice of nihilism, radical socialism or alien propaganda’. A defence against these ‘disintegrating influences’ was all that was intended by ‘America first’, a slogan ‘approved in the late election’ that was now government policy. ‘Every one within the United States should fall in step.’37

The threats of nihilism, radical socialism and alien propaganda that ‘America first’ was meant to combat were, by no coincidence, all corrupting influences associated with European intellectuals, many of whom were also Jewish. These radical intellectuals, with their alien ideas, were construed as threats to ‘ordinary’ supporters of ‘America first’, which – through another chain of associations – thus became a defiantly anti-intellectual position, as well. Rural populations felt that smug cosmopolitan elites – like the writer H. L. Mencken, who became famous for insulting the ‘rubes’ and ‘yokels’ of the Middle American ‘booboisie’ – were sneering at their morality and religion.

The result was that ‘America first’ was by no means only taken up by Republicans. Just after the election, Democrat Senator James Reed of Missouri told an ‘America First Thanksgiving’ celebration in Madison Square Garden: ‘We have emerged from dreamland.’ Reed was one of a bipartisan group of congressmen known as the ‘Irreconcilables’, who unilaterally rejected the Versailles Treaty in any form. ‘The American people have refused to haul down the American flag. We have emerged from dreamland. The people can always be trusted. Our Anglo-Saxon fathers realized that,’ Reed added, throwing in a little racial fillip for his listeners. ‘They knew, as Jefferson knew, that the common sense of the people was greater than all the knowledge of a few intellectuals.’38

This calculus unites Anglo-Saxons, the Founding Fathers, and the common people against foreign intellectuals who inhabit an unreal dreamland. (We should pause here and enjoy for a moment the idea that the erudite Jefferson, America’s first ambassador to France, was opposed to foreign intellectuals.) The charge that urban, intellectual, cosmopolitan citizens are less American, or less ‘real’, than rural, plain-spoken, provincial Americans is nothing new; it has underwritten the nation’s periodic eruptions of anti-elite populism for most of its history. And by 1920, it was associated with ‘America first’.

Reed’s ‘real America’, emerging from ‘dreamland’, was embracing what Walter Lippmann had deemed an illusion, the dream of the unvarnished wisdom of the common man, the power of anti-intellectualism writ large. By no coincidence, Lippmann himself was a first-generation German-Jewish immigrant from New York – exactly the kind of ‘alien’ public intellectual Senator Reed was encouraging his constituents to dismiss in the name of their ‘Anglo-Saxon’ fathers. Each group routinely accused the other of embracing delusions, of inhabiting a bubble of unreality.

Earlier in 1920, a former senator named Albert J. Beveridge addressed a ‘monster crowd’ in Indiana in similar terms, measuring the reality of his fellow Americans against their homogeneity. Beveridge was not merely for America first, he affirmed: he was for America only.

I am a nationalist; I am opposed to the League of Nations. I am a nationalist by birth, by conviction, by thought and for prudential reasons. Why, when this country was established it was a homogeneous nation. We are not such a nation now, but a conglomerate of racial groups with none outweighing any other. We are not a people as the French are a people, as the Italians are a racial entity. And until we are a people and racial lines are wiped out and we have become homogeneous in blood as well as in name and purpose, we cannot be the greatest nation possible, a distinctive race in the world. Not America first and Italy second, not America first and France second, not America first and Germany second, but America only should be our slogan.

The monster audience responded to these appeals for a purified ‘American race’, and its appeals to an entirely mythical racially homogenous past, with thunderous applause.39

* * *

All of this should make it come as little surprise that the Ku Klux Klan had also adopted ‘America first’ as a motto by 1920. In 1919 a Texas Klan leader gave a Fourth of July speech declaring, ‘I am for America, first, last and all the time, and I don’t want any foreign element telling us what to do.’40 The fantasy of an America once populated solely by the racially pure Nordic ‘common man’ was the Klan’s genesis myth as well, the prelapsarian past to which they hoped to force America to return – by violence if necessary.

Lynching posed enough of a national crisis that during the 1920 presidential campaign, Republicans were urged to add a plank to their platform that would make it a federal crime. That summer, the New York Tribune printed a letter from a reader advising the Republican Party to do so. On the same page, another correspondent argued that there had been ‘far too much appeal to racial elements. The country must be purged of all alienism.’ Americanism, he insisted, ‘stands not for “America First” – that implies doubt, as if there were secondary choices – but for “America Only.”’ Alienism and foreign elements were leading the country astray; ‘as Americans we can solve our own problems, so that every class, every race, every sect may be satisfied’.41 The author did not seem to see any contradiction in following his objection to too much pandering to racial elements, and a call for purging of all alienism, with an assurance that ‘every race may be satisfied’. The Republicans did not adopt an anti-lynching policy in their platform that year, making it unlikely that every race in America was satisfied.

Instead, states’ rights continued to be invoked as the pretext for allowing local governments to decide how, or whether, to prosecute lynching. Mostly they didn’t, and in the four years between 1918 and 1921, at least twenty-eight people were publicly burned at the stake in the United States.

Most American newspapers at least publicly denounced lynching by 1920. But the cognitive contortions required to rationalise racial violence have always created astonishing blind spots. For example, in July 1920, a North Carolina paper ran an editorial suggesting that the ‘America first’ slogans of Wilson and Harding were ‘just a little selfish’: ‘A year ago America led the world; today we are completely isolated.’

Right next to that leader condemning selfishness, the paper (ironically named the Washington Progress) ran an editorial threatening black Americans with lynching. ‘Another horrible outrage has been committed on a white woman by a brute of a negro and as a result another white man has been killed and several others wounded,’ it began, before descending into hysterical incoherence: ‘This is the second occurrence recently and the former negro was lynched and an attempt to lynch the last one [sic].’

Having paid brief lip service to morality and the law – ‘lynching is deplorable and cannot be approved’ – the editorial quickly got on with the business of blaming the victim:

But conditions are growing worse and will not be tolerated. The negroes might as well realize this fact once for all. If the best element of the colored people will [choose to,] they can aid in stamping this crime out and retain the good feeling that now exists between the races. No matter how much lynching may be deplored if this thing continues the crime of lynching will multiply.42

Summary violence would continue as long as black Americans did not improve their ways – by accepting the fractional citizenship allotted to them by white people.

Historians would later demonstrate beyond any reasonable dispute that violence against African-Americans was a backlash against the political and economic gains they made in this period, and that policing sexual boundaries was usually a pretext. The fact that ‘economic competition’ led to lynching was acknowledged by local American papers as early as 1903.43 The more minorities achieved economic autonomy and integrated themselves into the nation’s social fabric, the more retaliatory violence they provoked. (The idea of being ‘uppity’ – failing to know your place – is also the logic that allows oppressors to convince themselves that their victims had it coming, that provoking violence is the same as deserving it.)

That violence against black people was overwhelmingly economically motivated was occasionally impossible to ignore, even at the time. A local Nebraska paper reported in 1920 that ‘thousands of negroes’ had been forced by ‘white capped’ ‘night riders’ to work in the cotton fields of South Carolina. The headline described this enforced labour in slightly different terms, however: ‘Cotton Crop Saved by Action of Night Riders Wearing the Garb of the Kuklux Klan’.44 It seems that congratulations were in order for the Klan’s heroic decision to save a cotton crop by trying to temporarily resuscitate slavery.

Meanwhile, lynching was spreading out of the South. In 1920 the Dallas Express (‘The South’s Oldest and Largest Negro Newspaper’) noted that five years earlier a lynching in the North was so rare that it would dominate the news reports when it happened, whereas in the South it garnered much less attention.45 But in 1919, out of eighty-two reported lynchings in the United States, two were in Colorado, one in Washington state, one in Nebraska and one in Kansas.

In June 1920, three black men, circus workers named Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie, were lynched in Duluth, Minnesota, accused of raping a white girl. The alleged victim was later examined by a doctor who found no evidence of physical assault. No one was ever prosecuted for the murders.

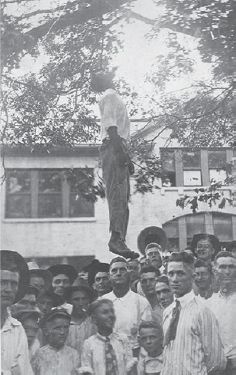

Two months later, a mob of over a thousand people stormed a Texas jail and lynched Lige Daniels, accused of murdering a white woman; photographs of his dangling body were turned into souvenir postcards. As ever, there were smirking white crowds below, including children.

Later that year, there was another triple lynching in Santa Rosa, California, in front of spectators, one of whom offered a ‘vivid’ eyewitness account of the ‘sickening’ event to the press.46

It was observed even at the time that the excuses offered for lynching had grown ever thinner, as if mobs could no longer be bothered to rationalise torture and murder. Once the only ‘adequate provocation’ acknowledged by public opinion was ‘the ravishment of a white woman by a Negro’, noted the same Dallas Express article. But now ‘public opinion has become more indulgent’.47 Among the ‘reasons’ offered for the summary execution of black Americans in the early years of the twentieth century were ‘wild talk’, ‘gambling dispute’, ‘wage dispute’, ‘debt dispute’ and ‘circulating literature’.

For the Klan, ‘America first’ offered a fig leaf: a xenophobia that was socially and politically acceptable was covering for a vigilante racism that was (at least officially) not, as they protested that they were purging ‘alien elements’, and that they had nothing against black people. But the fact is that the Klan only rarely attacked foreigners, whether recent immigrants or visitors from other countries. Instead the ‘alien element’ was a nativist euphemism for the wrong kind of American: the hyphenate kind, the kind with alien ideas, an alien name, an alien religion, or of an alien race.

* * *

But because the one-drop rule was impossible to prove (all drops of blood in fact look the same, after all), racial purity was much harder to police than groups like the Klan cared to admit. The possibility that people might be hiding their real origins, ‘passing’ as white, or even as American, is the kind of possibility that might make a nativist very anxious indeed. Anxious enough to develop conspiracy theories about the origins of people in power.

Which is why, in 1920, just before Harding was elected, he was accused of being black.

In October 1920 the press revealed a whispered underground conspiracy theory against the presidential candidate, designed by his opponents to keep his party out of the White House. It was, shouted the New York Herald headline, an instance of ‘Political Depravity and Moral Degeneracy to Shock the World’. They had uncovered ‘a dastardly conspiracy’ to ‘steal the election from the Republican party through an insidious assertion that Warren G. Harding, Republican candidate for President of the United States, is of Negro ancestry’.48

The accusation depended on widespread agreement that to be part ‘Negro’ was not only to be dishonoured, but to be disqualified from the presidency by virtue of not being ‘one hundred per cent American’ – which could be construed as being black, or foreign, or treasonous, or all three.

An outraged Republican chairman assured voters that Harding was ‘pure Anglo-Saxon’, while objecting that the unfounded charges being generally circulated, and widely believed, constituted ‘the most contemptible and scurrilous attack ever made by anyone on a candidate for this high honor’.49 It came as a shock to many that even in modern times the honour of the presidency was insufficient to shield a candidate from scurrilous rumours about his origins.

In an editorial reprinted around the country, a newspaper from Harding’s home state of Ohio angrily denounced the ‘whispering lies’ attacking the presidential candidate’s legitimacy. America was supposed to be moving on from ad hominem personal smears. ‘The presidential campaigns of the present century have been fought out chiefly in the open with arguments about principles and the characters and intentions of candidates.’50

But now Democrats were attempting to revive an ugly ‘underhanded partisanship’ in circulating the rumour that Harding had a black grandmother. No Democrat had endorsed this ‘sneaking propaganda’ officially, but they had all passed the pamphlets around behind closed doors.51

Defences of Harding sprang up, sharing his ancestry and family tree, carefully explaining exactly where his family came from (Lanarkshire, Scotland) and when (seventeenth century), while promising ‘to prove that there was not one drop of negro blood in any one of them’.52

‘As a rule Americans object to lies,’ the letter finished, ‘and particularly to that type of lie which flourishes only in the dark. Unless the character of our people has changed they will show on election day exactly what they think of the subterraneous campaign’ to discredit a president’s legitimacy on racial grounds with a whispering campaign. ‘A political campaign that cannot be run in the open free press of America is not to the credit of any party or candidate,’ they were certain.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that three Ohio papers had ‘denounced’ the rumour, declaring that ‘Warren G. Harding, pure in heart, pure in his Americanism, splendid in his fine patriotism, has in his veins only the pure blood of the white man, given him by a long line of culture ancestry, men and women of whom he may well be proud – proud in achievement, proud in their fine home life and ideals and proud in their pure race integrity’.53

All of these ‘purities’ were presented as, if not equivalent, then correlated: pure heart, pure Americanism, splendid patriotism, pure white blood, admirable culture, high achievement, fine ideals, pure race integrity – each becomes inextricable from the other.

From the ‘pure Americanism’ of ‘America first’ to ‘the pure blood of the white man’ in a few easy rhetorical steps. Nor would it be the last time in American history that the idea of too much ‘black blood’ was used to imply that a president was less than ‘one hundred per cent American’ and thus unqualified for office, although no one appears to have asked for Harding’s birth certificate.

That December, William Allen White, the nationally beloved journalist known as the Sage of Kansas, wrote a letter. ‘What a God-damned world this is!’ he said. ‘If anyone had told me ten years ago that our country would be what it is today … I should have questioned his reason.’54