During his 1920 ‘America first’ campaign, Harding notoriously announced that ‘government is a very simple thing’. If elected, he would just get things done. It would be very easy to be presidential, he promised.

‘Good government has almost been allowed to die on our hands, because it has not utilized the first sound principles of American business,’ he stated.1 Harding would put an end to that, promising to run the American government like a business, a promise that was welcome to many Americans, who thought becoming a business was just the remedy the country needed. He would put ‘less government in business and more business in government’, Harding pledged.2

‘The reactionaries are always talking about a businessman for president,’ wearily noted a Salt Lake paper; the Washington Herald observed that Democrats were also responding to the ‘widespread demand for a “businessman president”’.3

Assuring America he would liberate the nation from ‘war’s involvements’, Harding committed to sweeping reforms of the executive, to make it more efficient and effective. When he took office in March 1921, Harding had complete control not only of the White House but of both branches of government. The Republicans would remain in power, virtually unchecked by any real opposition, throughout the decade, as the Democrats became so unelectable that the two-party system all but broke down.

As he was preparing to enter office, Harding declared: ‘I believe most cordially in prospering America first.’4 While still enjoying the heady days of self-confidence, he published a collection of addresses soon after his inauguration called Our Common Country: Mutual Good Will in America. In it, he mentioned ‘America first’ thirteen times, associating the motto with the principles of good business. ‘All true Americans will say, as I say, “America First”! Let us all pray that America shall never become divided into classes and shall never feel the menace of hyphenated citizenship!’5 In a book that called for the ‘utter abolition of class’ division, Harding did so by conflating class with ethnic background; suddenly, the dream of democratic and economic equality looked a lot like one hundred per cent Americanism.6

In fact, under Harding’s presidency inequality would steeply rise. His definition of America first prosperity decidedly did not include social safety nets, enjoining an economic policy that ‘yields opportunity to every man not to have that which he has not earned, whether he be the capitalist or the humblest laborer, but to have a share in prosperity based upon his own merit, capacity and worth – under the eternal spirit of “America First”’.7

‘American business,’ he continued, ‘has suffered from staggering blows because of too much ineffective meddling by government.’8 Harding kept his promise to stop ineffective meddling by ceasing to do much of any meddling at all. Although his administration is often described as ‘laissez-faire’, theirs was less a policy of let go than one of anything goes.

Within his first year in office, Harding had discovered that governing was considerably harder than he thought. A blistering 1921 North Carolina editorial called ‘The Simplicity of Government’ heaped scorn upon his administration. ‘Mr. Harding remarked during his campaign that “government is a very simple thing after all”,’ it began. So it had proved, thanks to ‘the simple proposition of much promise and little performance’. Republicans were ‘loud-mouthed in the campaign’, when ‘almost anything was promised that looked like it might be a bait for the votes, but after the votes were procured, the party memory has suffered a lapse’.9

One of Harding’s promises was the reduction of taxes, a promise that was very appealing to ‘the fellows who had been making their barrels of profits’ and disliked paying taxes on them. They had voted trusting in ‘the time-honored republican custom of especially protecting those who protect the party’, knowing they would be able to ‘keep all their resources for their own use’.10

By 1922, many were mocking the self-exploding downward spiral of the GOP since their great 1920 victory.

Although we tend to describe the 1920s as a decade of economic boom, during which time the United States did experience eight consecutive years of growth, the bull market didn’t really take off until 1924, and lasted only until 1929. Harding inherited an economy in which war spending had far outstripped tax collection in an era before universal income tax. In an effort to balance the budget, the government slashed spending, resulting in a sharp recession for the first two years of the decade. Business failures between 1919 and 1922 trebled. Farmers were particularly affected by the recession, having taken out loans during the war at the government’s urging, and then been forced to default on them. Many never recovered; the foreclosure of small farms began not during the Depression of the 1930s, but during the recessions of the 1920s. And even in the midst of the boom, banks were failing: nearly six thousand banks were suspended during the 1920s at a rate of over five hundred a year, mostly in the Midwest and South.

Moreover, the bubble was short-lived. Not only was the stock market based on bogus values and commodities, including a vast number of Ponzi schemes, bucket shops and other shady or frankly crooked operations, but the stock market also had little to no effect on the real economy. Inequality only sharpened, as money was siphoned to the top.

Americans were tired of the years of chaos and uncertainty, the labour strikes and race riots, the bomb threats and progressive agitators, the muckrakers and constant wars, from the Mexican War to the Spanish-American War and then the Great War, which they had been assured would end all wars. They wanted stability and security, and Harding promised to deliver a ‘return to normalcy’ by putting America first, and particularly by restricting immigration, which had continued to explode in the wake of the war.

Between 1920 and 1921, 800,000 immigrants passed through Ellis Island, so that anxiety about America’s ability to absorb so many ‘foreign elements’ merely increased. Many argued that an influx of immigrants would only lead to further unemployment, while the Red Scare continued to fan racially inflected fears of domestic terrorism at the hands of anarchists. In early January 1920, at least three thousand people were captured and arrested as part of the Palmer Raids, during which five hundred people accused of being radicals and anarchists were abruptly deported, raids widely justified in terms of ‘one hundred per cent Americanism’, and supported by the Espionage and Sedition Acts of 1917 and 1918, passed by the Wilson administration, which had largely left its earlier progressivism behind.11

Although much reactionary violence was directed against blacks, Catholics and Jews in particular, a great deal of vigilantism was also targeted at radicals and socialists. In 1919, three former soldiers were shot and killed in Centralia, Washington, by snipers who were assumed to be members of the International Workers of the World. Locals ‘made a dash to raid the I.W.W. hall and round up all suspicious characters’, who were peremptorily ‘thrown in jail’. The man believed to be their leader was seized by a lynch mob; ‘they placed a rope around his neck, threw it over the cross-arm of a telephone pole and started to haul him up’. He was saved only when the police chief talked the crowd out of it, and was returned to jail, ‘almost dead’.12

In 1920 Upton Sinclair published a novel called 100%: The Story of a Patriot, partly inspired by the case of a radical named Tom Mooney, who was arrested and sentenced to hang for a 1916 San Francisco bombing on charges that were widely viewed as trumped up, and had been amplified by Hearst’s red-baiting local press. Sinclair’s novel is told from the perspective of Peter Gudge, ‘a patriot of patriots, a super-patriot; Peter was a red-blooded American and no mollycoddle; Peter was a “he-American,” a 100% American … Peter was so much of an American that the very sight of a foreigner filled him with a fighting impulse’.13

Peter fully believes that

100% Americanism would find a way to preserve itself from the sophistries of European Bolshevism; 100% Americanism had worked out its formula: ‘If they don’t like this country, let them go back where they come from.’ But of course, knowing in their hearts that America was the best country in the world, they didn’t want to go back, and it was necessary to make them go.14

For men like Peter ‘these were busy times just now. In spite of the whippings and the lynchings and the jailings – or perhaps because of these very things – the radical movement was seething.’15 All over the country, people asserting their rights were blamed for the violence their assertions called forth.

The idea that all radicals were foreign agitators – and that all foreigners were radicals – had become axiomatic to many Americans by the early 1920s, and more of the political climate than is often now recognised was driven by, or intrinsically related to, anti-immigrant sentiment. Even Prohibition, which came into law in January 1920, was in large part a way to criminalise the customs of immigrant groups. Old Puritan Yankee communities were mostly temperate, especially after the evangelical fervour of the Second Great Awakening in the first half of the nineteenth century had inspired an animus against the ‘demon liquor’.

Although the nineteenth-century temperance movement began, at least in part, as a broadly proto-feminist campaign (in an era when they were still legally and politically subject to their husbands, women sought prevention for alcohol abuse and domestic violence where there was no cure), temperance rapidly became entangled with anti-immigrant sentiments, as the Irish were associated with whiskey, Italians with wine. Just as religion offered a pretext for targeting ‘foreign elements’, so did alcohol offer a way to reject immigrant customs as inimical to a supposedly indigenous Americanism. It was also another way to demonise the elite, decadent pleasures of the city, to insist on the hearty purity of ‘real’ sober rural values over the delusive fantasies of urban sophistication.

Drinking was the vice of immigrants and aristocrats, the lower and the higher orders; those who repudiated it felt they represented ‘real’ Americans. Opposing alcohol was, as Walter Lippmann put it, ‘inspired by the feeling that the clamorous life of the city should not be acknowledged as the American ideal’.16 Thus a 1921 letter writer to the Tampa Bay Times complained that Mayor Hylan was not ‘one hundred per cent American’: ‘New York is not an American city by any means. It has a mayor who is far from being a one hundred per cent American … The real American favors the law and does not get together several thousands of foreigners, drunkards, gamblers, anarchists, white slavers, and such like, to enter a protest against the constitution of the government which is protecting them. If that crowd of un-Americans do not like the laws of this country the quicker they leave these shores the better for us.’17

For this correspondent, there was nothing to choose between drunkards, foreigners, anarchists and white slavers. They were all lumped together (‘and such like’), equally unreal, equally criminal and equally un-American. And anyone who supported them was less than ‘one hundred per cent American’, too.

That went for any foreigners. When the American Ambassador to Great Britain made a speech in which he dared to mention ‘the common interests of the United States and Great Britain’, he was excoriated by Democrat Senator Reed. The speech would be ‘treasonable if it were not idiotic’, Reed announced, demanding the ambassador’s recall. ‘We ought to put in his place a 100 per cent American who believes in America first and all the time.’18

* * *

Over the first months of his administration, Harding and his advisers cited ‘America first’ constantly as they urged renewed isolationism. Harding ‘stresses the America-first doctrine’, noted an Ohio paper, ‘and the menace of entangling foreign alliances’.19 As early as January 1921, papers were reporting that ‘“America First” will be policy’, that American ‘sovereignty will not be surrendered’.20 It was clear that ‘“America first” is the keynote of the platform of the new administration’.21 By the summer of 1921 there were ‘America First Societies’ across the nation, advocating, among other platforms, the boycotting of British and European goods.

By the end of 1921, a year after election, the Harding administration was trying to pass a permanent protectionist tariff in the name of ‘America first’.22

But for all its triumphalism, it was an expression that clearly continued to instil unease in many listeners. A few months earlier, a Pennsylvania editorial had written approvingly that Charles Evans Hughes should represent the Harding administration abroad, because he was ‘100 per cent. American. He stands for America first, but not for isolation.’23

Not everyone was convinced that America first could be so easily distinguished from isolationism. ‘We all are anxious to be known as 100 per cent American,’ a minister observed a few months after Harding’s inauguration. But ‘Americanism is not to think of America only’, he insisted. ‘If America first means America selfish, or America unmindful of world wrongs, we can hardly call it Americanism.’24 Others similarly noted a strong social pressure towards a patriotism expressed always in the same terms: ‘we must be 100 per cent American, we must be patriotic, we must stand by America first’.25

Just as Harding was inaugurated, the progressive Capital Times of Wisconsin demanded: ‘“America First?” For Whom? Is it America First for the financial rulers, or America First to make the world better? … Just what is this new concept of “America First” that has been set up by the Harding administration? Is it “America First” or is it “America Uber Alles?”’

‘America first’, the leader charged, was a pretext for tightening the grip of ‘the industrial octopus that is slowly fastening its tentacles on American life’. The protective tariff would ‘make it “America First”’ for ‘the imperialists and financial rulers of this country to get what they can get out of the world’. What the nation needed was ‘an “America First” that will seek to give to the world’.

Frequently breaking into outraged capital letters, the editorial urged that America should be ‘FIRST in the world movement against war, against armament, against imperialism, against national and racial hatreds, against tariffs that isolate us’. Most of all, America should stand first ‘against those sacred creeds of the economic rulers of the world that PROPERTY rights are above HUMAN rights … The American citizen will be first when he has the courage to say: “I love my fellow man wherever he may be found. I AM A CITIZEN OF THE WORLD.”’26

The Harding administration was less certain about that. In February 1921, Harding’s vice president Calvin Coolidge wrote an essay for Good Housekeeping called ‘Whose Country Is This?’ in which he declared: ‘Our country must cease to be regarded as a dumping ground’ and should only accept ‘the right kind of immigration’.

Clarifying what kind of immigration he had in mind, Coolidge endorsed eugenics and Nordicism to the American people. ‘Biological laws tell us that certain divergent people will not mix or blend. The Nordics propagate themselves successfully. With other races, the outcome shows deterioration on both sides. Quality of mind and body suggests that observance of ethnic law is as great a necessity to a nation as immigration law.’27

Not everyone agreed that keeping America ‘pure’ was possible, or even desirable. By the beginning of 1922, the Democratic candidate who had lost in 1920, James M. Cox, offered a biting assessment. ‘The echoing cry of “America First” is a mockery of human intelligence, as unhappy experience tells us that we are a part of the whole world.’28

* * *

As the American government’s association with ‘America first’ deepened, so did the Klan’s. By February 1921, newspapers all over the country, from Indiana and Oregon to Colorado and New York, from Baltimore and Montana to Texas, were reporting the adoption of ‘America first’ by the KKK. ‘The motto of the 1921 Ku Klux Klan is in its substance “America First”,’ wrote an Indiana paper in a feature reprinted throughout the state, noting that the Second Klan was a ‘revival of the famous organization of the reconstruction period in the south’.29

The Klan had made its association with ‘America first’ official by 1921, issuing a proclamation of its ‘ABCs’, in a circular picked up by papers around the country: ‘The ABC of the Klan is America First, benevolence, clannishness.’30

Some of the charter members of the Second Klan included ‘a few survivors of the old Klan’, the New York Tribune explained; it was now sharing its ‘creed’. The Klan’s creed included the promise: ‘We shall be ever devoted to the sublime principles of a pure Americanism and valiant in the defense of its ideals and institutions. We avow the distinction between the races of mankind as same has been decreed by the Creator, and shall ever be true in the maintenance of white supremacy.’

At the same time, the Klan held a public meeting in Birmingham, Alabama, at which the ‘Imperial Wizard’ W. J. Simmons declared that the organisation stood for:

1.One hundred per cent Americanism and reconsecration to bedrock principles.

2.White supremacy.

3.To protect woman’s honor and the sanctity of the home.31

Klan leaders circulated pamphlets around the country, repeating their ‘creed’ of ‘America first, benevolence, clannishness’. They protested that the Klan did not support ‘any propaganda of religious intolerance or racial prejudice’; the group was simply ‘an association of real men’ who believed ‘in doing things worth while and who are 100 per cent American in all things’.32

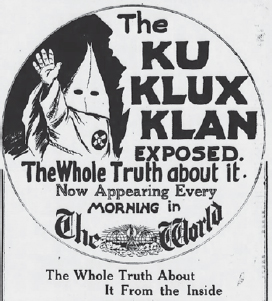

The Evening World ran a front-page exposé of the Klan in September 1921. ‘Secrets of the Klan Exposed’, read the first headline.

In five years, the World noted, the Klan had grown from thirty-four members to almost 500,000 nationwide, spreading through the north and west more than twice as rapidly as it spread in the south, thanks to a ‘highly organized sales force’. Millions of dollars were going to salesmen in commissions; the Klan was, to paraphrase later historians, America’s most successful racist pyramid scheme.

Schoolteachers and local politicians who happened to be Catholic were being forced out of their positions; ministers who were Klansmen ‘preach hatred of the Jew even in church pulpits’. Mobs of Klansmen had stripped and ‘maltreated’ white women, whipped, tarred and feathered white men for ‘private conduct’ of which they disapproved, and had ‘warned’ newspapers to be careful how they reported on the Klan.33

Over the next three weeks, the World published daily front-page reports of the Klan’s secretive activities, and introduced Americans to such arcane rituals and codes as ‘kleagles’, ‘klaverns’ and the Kloran. The last item is a particularly ironic appropriation in light of reactionary American politics in the early twenty-first century, but the silliness of the Klan’s occult nationalism was not lost on contemporary observers, who noted its willingness to embrace anything that sounded vaguely mystical or esoteric.

As an American historian would observe in 1931, reflecting on the Klan of the 1920s:

the preposterous vocabulary of its ritual could be made the vehicle for all that infantile love of hocus-pocus and mummery, that lust for secret adventure, which survives in the adult whose lot is cast in drab places. Here was a chance to dress up the village bigot and let him be a Knight of the Invisible Empire.34

The World concluded its 1921 reports by denouncing the Klan as supporters of ‘terrorism’, who ‘kidnap, beat, tar and feather victims, then turn them loose on other communities’. It listed four recent murder victims, as well as over forty floggings and twenty-seven ‘tar and feather parties’.35

The revelations were reprinted around the country, reaching more than two million Americans a day. The World’s expressed opinion was that the exposure would destroy the secret organisation, but their optimism was misplaced. In fact, some historians have argued that the effort backfired, bringing much needed publicity to the Second Klan; recruitment surged, and the Klan established over two hundred new chapters in the four months after the World’s disclosures.36

It was perfectly clear to all at the time that the Klan was a terrorist organisation, and intended as one. (Indeed its rituals referred to Klan officers as ‘Terrors’.37) The governor of Kansas stated outright: ‘I am opposed to the Klan because it suggests terrorism.’38 A 1921 cartoon reprinted around the country shows a leg wearing Uncle Sam trousers and labelled ‘True Americanism’ giving the boot to a figure in the robes of the Klan, who holds a sign reading ‘Terrorism’.39

No one in the 1920s was in any doubt about whether white men could be terrorists.

On 1 January 1922, many readers across America greeted the new year with a front-page report from the Tuskegee Institute that sixty-four people had been lynched in America during 1921; fifty-nine were black, five were white, and two were women.40 Four had been burned alive.

Those were just the lynchings that were reported. Seventy-two were stopped; it is impossible to know how many others might have taken place around the country that were never discovered. Mississippi had the most in the country that year, at fourteen; there were seven in Texas.

A few weeks later a Klan parade in Alexandria, Louisiana, bore two flaming red crosses and banners with slogans including ‘America First’, ‘One Hundred Per Cent American’ and ‘White Supremacy’. They also carried signs reading ‘Race Purity’, ‘Good Negroes Are Safe, Bad Ones Beware, Whites Ditto’ and ‘Abortionists, Beware!’41

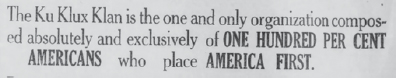

That summer the Klan took out an ad in a Texas newspaper, equating ‘America first’ with ‘one hundred per cent Americans’.42

A report in November 1922 that the Klan was attempting to establish an outpost in the heart of Times Square, at the Hotel Hermitage on Seventh Ave and 42nd Street, led Mayor Hylan (who clearly had his virtues) to announce that there was a ‘Klan drive’ on in New York City, and instruct the police to ‘rout them out’.43 They responded that they ‘refused to be intimidated’; intimidation was a right the Klan reserved for themselves. The Hotel Hermitage, meanwhile, said they would not ‘harbor a man who endeavored to foment bigotry’44 and kicked the Klansman out.

Three weeks earlier, a young black man seen kissing a white woman had barely been rescued from a lynch mob on West 45th Street, about six blocks away.45

By February 1923, the New York Times was reporting that three flaming crosses had appeared ‘to frighten Negroes in Long Island towns’, while that summer 25,000 new Klansmen were said to have joined the organisation in an initiation ceremony near East Islip.46

Groups with names like the 100% Americans began recording songs glorifying the Klan:

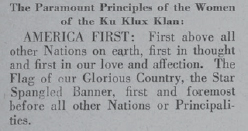

The Klan established an ‘official’ women’s branch in November 1922, which published a pamphlet, ‘Women of America! The Past! The Present! The Future!’, outlining their beliefs and formally adopting the Klan’s ABCs of America first, benevolence and clannishness.

* * *

The earliest mention of ‘fascism’ in the American press seems to have been in early 1921, when an Italian correspondent in Rome wired a special to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the Philadelphia Public Ledger, in which he explained that ‘no doubt Fascism is a transitory phenomenon’, a reassuring message that was picked up by papers around the country.47 But throughout 1922, as Mussolini’s corporate state consolidated power in Italy, many American observers concluded that fascism looked all too familiar.

The New York World offered a homespun analogy to explain the ‘Fascisti’ to its readers within weeks of Mussolini’s seizure of government: ‘in our own picturesque phrase they might be known as the Ku Klux Klan’.48 The Tampa Times agreed: ‘The klan, in fact, is the Fascisti of America and unless it is forced into the open it may very easily attain similar power.’49

It no more requires hindsight to view the Second Klan as a fascist organisation than it does to view it as a terrorist one: once again their contemporaries could instantly see the likeness – and the danger – all too clearly. In fact, the comparison was widespread. ‘Encouraged by the signal success of the Fascisti or Italian Ku Klux Klan,’ wrote the St Paul Appeal, the American Klan was similarly seeking ‘political power in the United States’.50

The Minneapolis Star Tribune had reported in the summer of 1921 that ‘The Fascisti is a secret order having some of the Ku-Klux Klan method’.51 In Philadelphia a year later they were described as ‘Those obstreperous reactionaries who under the name of the “Fascisti” are playing a part in the public affairs of Italy closely analogous to that which in some sections of the United States has been assumed by members of the Ku Klux Klan’.52 ‘The Fascisti assumed some of the characteristics of the Ku-Klux-Klan,’ agreed the New York Tribune, ‘and their methods could hardly be justified in anything like a law-abiding democracy.’53

By November 1922 a Montana paper had noted that in Italy, fascism meant ‘Italy for the Italians. The fascisti in this country call it “America first.” There are plenty of the fascisti in the United States, it seems, but they have always gone under the proud boast of “100 per cent Americans.”’ ‘The democrats may say it was the American fascisti that won the election in 1920,’ the article surprisingly concluded, a Montana newspaper explicitly calling Harding’s Republicans fascists.54

Three weeks after papers around the country reported that Mussolini’s Blackshirts had seized power in Rome, with ‘Italy Firmly in Grip’ of the Fascists, the first mention of a rising German fringe politician also appeared in the pages of the New York Times. His name was Adolf Hitler.

Hitler’s anti-Semitism seemed disturbingly violent, the Times reported in its first account of him, before quoting a senior German statesman who advised everyone not to worry. ‘Sophisticated politicians’ in Germany believed Hitler’s anti-Semitism was merely a campaign tactic, a ploy to manipulate the ignorant masses. Because the general population can never be expected to appreciate the ‘finer real aims’ of statesmen, the politician explained, ‘you must feed the masses with cruder morsels and ideas like anti-Semitism’ rather than the higher ‘truth about where you are really leading them’.55 After the campaign, they were all certain that Hitler would shift to the centre, and become perfectly reasonable.

The Times correspondent clearly disagreed, warning, ‘There is nothing socialist about the National Socialism’ being preached in Bavaria, while Hitler ‘probably does not know himself just what he wants to accomplish’. However ‘the keynote of his propaganda is violent anti-Semitism’, the correspondent repeated, adding that some Jews were already leaving Germany.56

That year, a young American journalist named Dorothy Thompson was living in Vienna, where she had just been made a foreign correspondent for the Philadelphia Public Ledger and Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Within a few months, Thompson was reporting on the rise of anti-Semitism in Vienna, and on ‘what Fascistic Italy really thinks’ from Rome.57 By November 1923, Thompson was in Munich trying to get an interview with Hitler following his abortive Beer Hall Putsch; having failed, she filed articles describing ‘Hitler’s little Boy Scout show’, including the many other factions in Bavaria plotting to destroy the German republic, and the way Hitler had updated ‘Bismarck’s dream’ thanks to ‘suggestions from Mussolini’.58

‘The “fatherlandish” organisations’, wrote the Des Moines Register that summer, are ‘Germany’s Ku-Klux Klan’.59 A few months later, American papers shared the first published photograph of Hitler, ‘probably Europe’s most famous camera dodger’. Whatever his aversions to publicity might once have been, Hitler would soon get over them.

Next to the photo of Hitler was a report complaining that, as foreign policy, ‘America first’ was meaningless. ‘The cry “America First” is used in Europe as in America more as a camouflage to disguise an utter lack of foreign policy,’ an indecision that was ‘very detrimental’ to American prestige internationally.60

Just before Hitler had made his debut in the New York Times in 1922, a Washington Times columnist asked his readers: ‘Has it occurred to you that our American Fascisti are the gentlemen of the Ku Klux Klan? This country has no conception of their power and growth.’ The columnist had been told by a well-informed Washington insider that seventy-five members of the new Congress were also members of the ‘Ku Klux’.61

A month later, the St Paul Appeal reported that a meeting of the majority of the governors of the United States had refused to denounce the KKK, leading to the conclusion that the ‘silence of most of the governors on the Klan issue would appear to give weight to current rumors that most of them were elected by the Klan’.62

The governor of Oregon warned that the Klan could lead America to another civil war, as it was ‘gaining an amazing grip’ across the country. The problem was that ‘the tolerance with which the Klan was at first regarded was due to the belief that it was merely anti-Negro and not anti-anybody else’.

It was one thing to be ‘anti-Negro’: evidently the white citizens of Oregon had no objection to that. But once they discovered the Klan was anti-others, including perhaps themselves, they began to protest. ‘The same sort of outrages – committed by night riders, masked in white gowns and cowls – that have swept the Southland have repeatedly occurred in Oregon, so that law and order is as much usurped by the American fascisti as in Louisiana.’63

Across the country, from Philadelphia and Iowa to Montana and Oregon, American citizens were confronted with the Klan and the Italian Fascists marching across the front pages of the news, in seeming lockstep. No one missed the comparison.

At the end of 1922, the Klan decided to make it official, announcing its intention to create an ‘alliance’ with Mussolini’s Fascists. The Imperial Giant of the Ku Klux Klan promised at the annual ‘Klonvocation’ in Atlanta that as part of the Klan’s ‘European expansion program’, the ‘Fascisti will join with us in establishing the klan in Italy’.

This ‘expansion program’ was usefully clarified by the Atlanta correspondent as ‘the klan’s plan to invade Europe and organize for the maintenance of white supremacy throughout the earth’.

Some prominent Klan members expressed shock that the Imperial Giant was prepared to allow Roman Catholics, their avowed enemy, to join the Klub. The Imperial Giant argued that all ‘white Christian men’ were welcome to become members. Jews and blacks, of course, were still right out.64

By the beginning of 1923, the links among 100 percenters, the Klan and fascism were so obvious that they began to parenthetically define each other. A reader wrote to the Des Moines Register objecting to the fact that the country was governed by an economic elite, the ‘two per cent who rule this country’. These plutocrats had chosen to ‘foster and encourage such organizations as the American fascisti (K.K.K.) and the so-called 100 percenters of capitalism’s praetorian guard, the [American] legion. Both are “patriotic,” “100 per cent Americans,” ready to “Americanize” anything at the drop of a hat,’ the writer noted, putting all of the phrases in sceptical scare quotes, while adding that 100 per cent Americanism kept allying itself to fascists and plutocrats.

‘The purpose of these organizations was and is the suppression of free speech, free press, and free assemblage, unless such freedom is authorized by a “kunnel”,’ while their ‘midnight parades in dunce caps and cotton nighties are preludes to arson, murder, and deportation’.65 Two months later the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported ‘an open declaration of the American Fascisti, known as the Ku Klux Klan’.66

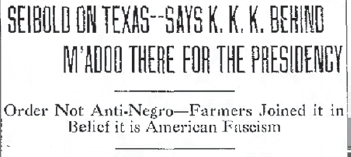

That summer reports began to circulate that the Klan was behind the bid for the presidency of Southern Democrat William G. McAdoo, the cabinet member (and son-in-law) who had urged Woodrow Wilson to institute federal segregation. The Texan farmers who joined the order of the KKK and supported McAdoo’s candidacy were adamant in their claims that the Klan was not ‘anti-Negro’. It was merely a wholesome ‘American Fascism’.67

To be sure, none of the Texan farmers insisting their group wasn’t racist, just fascist, yet knew the horrors European fascism would perpetrate. What little they knew about fascism they would have gleaned mostly from celebratory editorials like the one offered by the El Paso Herald after Mussolini came to power, reporting that Il Duce had been greeted rapturously by ‘Fascisti organizations’ in London and Paris, and informing their readers that these groups were ‘good organizations. Their existence is one of the most hope-inspiring things in the world today.’68

The editorial helpfully identified what was so inspiring about fascists: their public love of country, their opposition to radicalism, and their determination to uphold government authority. However, it went on to concede, fascists ‘are not altogether good’. Sometimes ‘they disregarded law and substituted force under the plea of necessity’.

The good news was that ‘displays of violence by Fascisti have been rare, and sporadic’; it was mostly the discipline of ‘a well-ordered military force’. In the end, ‘Fascism is wholesome, good for those parts of the world that seem to need it, when it is an ordinary, law-abiding demonstration of patriotism. It is certainly an effective rebuke to radicalism.’69 Nothing says ‘rebuke’ like the regrettable necessity of illegal violence.

Defences of Italian Fascism were not restricted to the south. The Chicago Tribune also cheered on Fascist ‘rebukes’ against radicals. ‘We have no respect for the fuss made over Fascist violence directed against a body of revolutionists which had not hesitated to use violence in their own cause,’ a 1922 editorial pronounced. ‘It is easy for American ideologues and parlor pinks to condemn the Fascisti for the use of illegal force, but Fascism confronted conditions, not theories.’70 Anyone objecting that the clue was in the word ‘illegal’ could look forward to being dismissed as just another parlor pink.

In fact, the American press offered plenty of examples of fascistic violence, evidence that many observers chose to ignore as they used it to justify their own ethno-nationalist positions. ‘Everyone knows,’ observed the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, that ‘Italian workers under the Fascist Government do not dare to strike, having been completely cowed into temporary submission by Fascist violence.’ ‘Democracy,’ it ended, at least for the time being, ‘is dead in Italy.’71

‘The Fascisti launched a campaign of destruction,’ readers in Muncie, Indiana, were informed, and ‘the program of violence continued until after the election in July, 1921’, at which point the violence was ‘somewhat diminished’.72

Somewhat.

* * *

As for home-grown American fascism, whatever the El Paso farmers supporting McAdoo wanted to tell themselves, any American alive in 1922 was well aware of the actual ‘anti-Negro’ activities taking place. Lynching was condemned in newspapers across the country, while throughout 1922, the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill (first proposed in 1918) was debated in Congress.73 President Harding had spoken out against lynching in 1920. ‘I believe the federal government should stamp out lynching and remove that stain from the fair name of America,’ he announced, winning the approval of papers including the African-American Buffalo American, whose allegiances with the Republicans as the party of Lincoln were long-standing. ‘I believe Negro citizens of America should be guaranteed the enjoyment of all their rights,’ Harding stated, adding, ‘they have earned the full measure of citizenship bestowed’.74

Harding spoke in favour of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in 1921, which passed the House in 1922 before Southern Democrats in the Senate filibustered, killing it. Some threatened that they would not enact a single piece of legislation that year if the bill were to pass, effectively holding the Senate hostage to their extreme partisan position.

The Buffalo American ran an editorial on the Dyer bill, arguing that it should represent the principles of ‘America first’, and commending Representative Dyer for his battle on its behalf. ‘Unless he had been a 100 per cent. American, who is interested in that doctrine, so familiar in campaign times but forgotten now, “America First,” he would not have stood and fought, not for a race, but humanity and human rights.’ It was vital that ‘the Administration’s slogan, “America first”’,’ not be forgotten along with ‘the tenth part of the population’.75

The Dyer bill failed, as did the Buffalo American’s poignant effort to extend the principles of ‘America first’ to cover all Americans, including the 10 per cent who were black. In the first half of the twentieth century, nearly two hundred anti-lynching bills were introduced to Congress. None of them passed.

African-Americans staged a ‘Silent March on Washington’ in support of the Dyer bill on 14 June 1922, forty years before Martin Luther King Jr would make his voice – and his American dream – heard.

While the Senate was filibustering the Dyer bill, the Boston Globe wrote a scathing editorial called ‘The Right to Lynch’, which was reprinted in the African-American Dallas Express, along with several other national condemnations. ‘The Democrats do not like the Anti-Lynching bill,’ the Globe noted, ‘and are willing to talk themselves hoarse in order to prevent a vote upon it.’

This was a surprising position for them to take, the Globe’s editors observed, ‘for the Democrats have given up their traditional position in favor of States’ rights on all issues save one. Time and again they have favored a strong central Government, but make an exception in reserving the right to burn Colored people at the stake.’76

Alongside a cartoon depicting ‘Our Own Hooded Kobra’, lurking outside the Government of Laws, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle ran an item entitled ‘American Fascism’, connecting the Klan to fascism and 100 percenters. ‘One factor common in all countries is the appeal to a pseudo-patriotism. The Italian Fascista is extremely patriotic, after the manner of “100 percent” patriots everywhere.’77

Saying that the proto-Fascist dictatorship of Primo de Rivera in Spain (whose son would establish a Fascist Falange party ten years later that soon merged with Franco’s), and Mussolini in Italy, were forms of the same ‘100 percent patriotism in Europe’, it argued that America was also rapidly heading in the direction of ultra-nationalist violence, thanks to the KKK. ‘There should be no misunderstanding about the Klan. It represents in this country the same ideas that Mussolini represents in Italy; that Primo Rivera represents in Spain. The Klan is the American Fascista, determined to rule in its own way, in utter disregard of the fundamental laws and principles of democratic government.’

If such people were allowed to take over the country, it cautioned, ‘we shall have a dictatorship.’78

* * *

Meanwhile Italians in America, and Italian-Americans, were also joining Mussolini’s Fascists. The ‘New York Fascia’ had been established as the ‘parent body’ for local groups of Mussolini supporters around the United States, including the ‘Baltimore Fascia’; all were taking ‘instructions from Premier Mussolini’.79

Ironically enough, one of the concerns created by American fascists who followed Mussolini was that they were, by definition, ‘hyphenates’, with allegiances beyond the United States. Newspapers around the country debated in 1923 whether American fascist movements posed a danger to the US. The name was against it, said the Springfield Republican, for its ‘emphasis on racial solidarity – a pan-Italianism as it were’, could only perpetuate ‘hyphenism’. The Tacoma Ledger agreed, calling American fascism an ‘affirmation by the Italian government’ that an American citizen still retained allegiance to ‘the mother country’. This would make fascism ‘as great a menace to Americanism’ as had been German support a decade earlier.80

Although both the Klan and the fascists liked to claim that their positions were purely ideological – and certainly they were willing to inflict violence on ideological grounds – they also had a tendency to conflate capitalism with white supremacy. In the spring of 1923, a Republican politician was urging the South to ‘lead [the] fight on radicals’, telling Arkansas farmers that ‘Reds Are Inciting Negroes’, and urging retaliatory ‘action by pure American stock’. Warning of ‘Communist efforts to incite the negroes to commit acts of violence’, he argued that the South was ‘the most natural and appropriate’ place ‘to start a counter-movement against radicalism in America’, because of ‘the racial purity and political traditions of the Southern people’.81

By a strange coincidence, people of ‘racial purity’ were the natural enemies of ‘radicals’, returning to the nativist associative chain that declared war on everyone who was not ‘pure American’, whether ethnically, racially or ideologically.

But not all Americans who called themselves fascists were supporting Mussolini. That spring papers around the country reported that ‘what is believed to be the first American Fascisti organization’ was being formed in Nebraska by a ‘deposed Kleagle’. The ‘American Fascisti’, explained a spokesman, was ‘a law-and-order society’. They would follow their Italian counterparts in opposing ‘the Socialists, Communists and strong revolutionary labor groups’ but ‘it would be in no way an enemy or an imitator of the Ku Klux Klan’.82

Like the Italian Fascists, they would wear black shirts, but no masks; 15,000 shirts had been manufactured and ‘a monster meeting’ was planned. ‘It would not mix in political or religious disputes,’ the spokesman said – except against socialists, communists and labour organisers, which evidently didn’t count as ‘political disputes’.83 This ‘non-political’ organisation would ‘oppose the “Reds” and the Klan’, according to the former Kleagle who established it, but would ‘embody all the good features of the latter organization’.84

The ex-Kleagle neglected to specify those good features, but many Americans picked up on the idea that American fascists would be less dangerous than the KKK if they were less secretive. It would not be surprising if ‘the fascisti movement’ spread rapidly throughout the United States, predicted one Nebraska paper; there were said to be some 20,000 American fascists already. ‘In some respects the American fascisti resemble the ku klux, but are apparently not cursed with the degree of secrecy that makes the hooded riders a menace to public safety.’85

It seems unlikely that the thousands of Americans being intimidated, press-ganged, branded, tarred and feathered, assaulted, terrorised, tortured, hanged and even publicly burned at the stake in broad daylight would have agreed that secrecy was what made the Klan a menace.