While America was confronting its spiritual failures in 1933, Europe was confronting the Nazis’ consolidation of power: Roosevelt was sworn in as president almost exactly one month after Hitler became chancellor. Three weeks after that, the Chicago Tribune was reporting that he had ceremoniously opened his first concentration camp, ‘at Dachau, near Munich’, on 22 March 1933.1

Two years earlier, the journalist Dorothy Thompson had interviewed the chancellor, calling him ‘inconsequent and voluble, ill-poised and insecure. He is the very prototype of the little man.’2 In I Saw Hitler, her 1932 book based on the interview, Thompson noted that Mein Kampf was ‘eight hundred pages of Gothic script, pathetic gestures, inaccurate German, and unlimited self-satisfaction’.3

Perhaps the most extraordinary part of Hitler’s rise, she thought, was its very premise: ‘Imagine a would-be dictator setting out to persuade a sovereign people to vote away their rights.’4 She would later be mocked for having ‘dismissed’ Hitler in this first assessment, but although she underestimated dictators, she also overestimated voters.

When Hitler took control, Thompson was aghast at his electorate’s self-deception and self-destruction, writing that Hitler had not been ‘thrust upon’ the German people; instead ‘dictatorship was accomplished by popular will … He recommended himself to them and they bought him.’ More than 50 per cent of German voters ‘deliberately gave [up] all their civil rights, all their chances of popular control, all their opportunities for representation’. In sum, ‘they bought the pig of autocracy in a poke’.5

Hitler came to power ‘largely because so-called civilized people did not believe that he could’, Thompson warned. The problem was that they complacently assumed that their idea of civilisation was ‘greatly cherished by all men’, who agreed that their culture, a ‘complex of prejudices, standards and ideas’, had been ‘accumulated at the cost of great sacrifice’ over centuries.

Instead, the intellectual elite needed to understand that ‘this culture is, actually, to the vast masses no treasure at all, but a burden’. And if economic conditions deteriorated, leaving those people resentful, ‘hungry and idle’, they would only view such ‘civilization as a restraining, impeding force’.6

At which point, they would identify smashing that system as freedom.

* * *

As European fascism was taking serious hold, the one hundred per cent American kind found itself in increasing trouble. The Klan was in decline by 1930, its political influence waning after electoral failures, while financial and political scandals, including accusations of election fraud, graft and bribery, further undermined its leaders. The New York Times had declared ‘The Klan’s Invisible Empire is Fading’7 as early as 1926, and by the late 1920s estimates of national membership dropped down to a few hundred thousand. After the 1929 crash, many rural farmers found themselves no longer in a position to pay $10 for membership.

Klansmen were also, some historians have suggested, at least partly a victim of their own success: having driven out the African-Americans they feared were economic competitors, they found themselves without an economic minority to exploit, no one to press-gang into picking their cotton for them.8 They may have found themselves with less spare time for inflicting violence.

As the Klan declined, however, more groups of self-styled ‘American fascists’ began to take its place. In the summer of 1930, papers around the country reported with some anxiety that for two months Atlanta had been ‘seething over the activities’ of a new group called the ‘American Fascisti’, who in practice preferred to call themselves simply ‘Black Shirts’. Although it promised to combat the spread of Communism, in reality, as reports soon showed, its members were targeting African-Americans. ‘Membership is restricted to native-born white Americans.’ Black shirts were the official insignia, and its sponsors denied ‘any connection with the Ku Klux Klan’, calling it a ‘spontaneous movement’.9

‘Born out of the throes of unemployment and the canny exploitation of what its leaders term a Communistic threat to white supremacy, the organization claims to have enrolled 27,000 members,’ reported the Baltimore Sun.10 They were not Italian-American followers of Mussolini; they were nativist supporters of a home-grown American fascism. The main leader of the American Blackshirts, unsurprisingly, was a former member of the KKK.

Along with the ‘American Fascisti’, two other groups were ‘stirring racial agitation’ in Atlanta, reported an Illinois paper in 1930: ‘the White Band of Caucasian Crusaders, and the Ku Klux Klan. For the moment the American Fascisti appears the most active. The White Band perhaps is next, and the Ku Klux Klan seems but a shadow of its former self, although no one is exactly certain as to its exact strength.’11

That summer, around seven thousand ‘American Fascisti’ paraded in Atlanta, carrying banners, one of which read: ‘Back to the cotton patch, Nigger – it needs you; we don’t!’12 Threatening Atlanta employers with boycotts and violence if they didn’t fire their African-American workers, the ‘American fascist association and order of the black shirts’ soon found itself facing Grand Jury indictments.13

In the spring of 1930, an Oakland newspaper ran a section of ads for fraternal societies that were seeking membership, among them the Klan, which was struggling to recruit new members. ‘All Native Born Protestant Americans are invited to join the KU KLUX KLAN. This all American organization is now conducting a vigorous drive for fifty thousand new members. We are after the state convention for 1932. Now is the chance to join the fraternity that has the backbone to stand for America FIRST, LAST and ALWAYS.’14

But even if the Klan was disintegrating as an organisation, its former members had not suddenly renounced their beliefs – or their willingness to use peremptory violence to impose them. Ten days after the Oakland Klan sought to recruit new members, the Negro Labor Congress announced a campaign against ‘lynching and other forms of white terrorism’.15

It was none too soon. August 1930 brought the notorious double lynching in Marion, Indiana, of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, whose dangling bodies were photographed over grinning and pointing white crowds. Such photographs had long circulated, but now they were making their way into the papers. The photograph of Shipp and Smith, which rapidly became iconic, inspired the anti-lynching lament ‘Strange Fruit’, originally sung by Billie Holiday.

The Evening Press of Muncie, Indiana – about forty miles south of where the lynchings occurred – published the photo on its front page.

The caption reads: ‘This remarkable picture – gruesome as it may be – was taken at Marion last night just a few minutes after two negroes, who admitted killing a white man and attacking a white girl, were hanged from trees in the courthouse yard. They had been badly beaten, stabbed and dragged across a cement walk – all this the picture shows. Only a small portion of the milling mob is shown in the photo.’16

Gruesome was one word for it; neighbouring Muncie was not, it seems, prepared to use a stronger one. Next to the photo of two men dangling from trees, the editors, stupefyingly, printed a column with the subhead ‘It’s In the Air’, which opened: ‘When times are really getting better you can feel it in the air.’

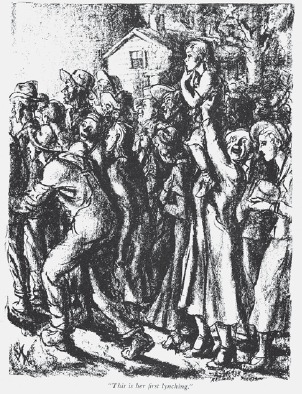

The lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith has sometimes been identified as the last public lynching in the United States. Sadly, it was not. Spectacle lynching was still active enough in 1934 to provoke a blistering New Yorker cartoon from the artist Reginald Marsh, of a white woman holding up a small blonde girl in an excited crowd, happily telling her neighbour: ‘This is her first lynching.’17

Less than two months after Marsh’s cartoon appeared, Claude Neal was lynched in Marianna, Florida, in front of an estimated crowd of five thousand, accused of raping and murdering a white woman. It was ‘advertised hours in advance’, reported the New York Times, ‘bringing together thousands of men, women and children eager to witness the spectacle’. The lynching itself was ‘marked by unspeakable torture and mutilation’.18

The torture and mutilation that papers at the time would not name were itemised by a white undercover investigator for the NAACP, to whom an eyewitness boasted ten days later:

‘They cut off his penis. He was made to eat it. Then they cut off his testicles and made him eat them and say he liked it. Then they sliced his sides and stomach with knives and every now and then somebody would cut off a finger or toe. Red hot irons were used on the nigger to burn him from top to bottom.’… From time to time during the torture [the investigator continued] a rope would be tied around Neal’s neck and he was pulled up over a limb and held there until he almost choked to death, when he would be let down and the torture begun all over again.19

After Neal’s body was cut down, the mob stamped and urinated on it, drove cars over it, and small children stabbed it with sticks.

Some local papers had announced in their morning editions the imminent ‘lynch party’ later that day. The Dothan Eagle, from neighbouring Alabama, had explained in an afternoon headline on the day of the lynching exactly what was planned: ‘Florida to Burn Negro at Stake: Sex Criminal Seized from Brewton Jail, Will be Mutilated, Set Afire in Extra-Legal Vengeance for Deed’.20

Another headline informing locals of the lynching to come had read: ‘Ku Klux Klan May Ride Again’.21 The Klan was down, but it wasn’t out.

* * *

As the Klan found its grip on reactionary sentiment in America slipping, ‘America first’ continued to be brought into disrepute by others using it as well. When Big Bill Thompson tried to rally support once more for his faltering America First Foundation, he generated more ridicule than riches.

Increasingly it looked spent as a political force, as even Thompson was forced on occasion to concede. When asked in 1930 about ‘the “America First Foundation,” his child in 1927’, the blustering Thompson replied with an uncharacteristic sigh, consigning it ‘to the past tense: “America first went along and did a lot of good,” he said. “The results of it can be found in the United States senate.”’22

But then Mayor Thompson gave it another shot, inviting William Randolph Hearst to help celebrate ‘Chicago Day’, commemorating the great Chicago Fire of 1871. The theme of the day was ‘America first’. ‘“America First” Hearst,’ read the headline.23

A few weeks later, in Marion, Ohio, the home of Warren G. Harding, another politician took the stand with ‘America first’. Seeking re-election in the midterms, Senator Roscoe McCulloch returned to the oldest version of the slogan, insisting, ‘we must think of America first and the rest of the world afterward’. ‘The issue is clearly drawn,’ he asserted: ‘Americanism against internationalism; expatriated capital against American capital, invested in home industries; American working men against foreign workmen. And the protective tariff is all that will save us.’24

Local politicians were also still adopting the ‘America first’ slogan, combining it with other coded claims about one hundred per cent Americanism: a platform of ‘America First’ and ‘America for Americans’ should ‘make it clear to the world that America’s door is open only to those who come with the declared intention of becoming loyal American citizens’, contended state representative Virgil A. Fitch, running for re-election in Michigan; his campaign advertisements promised ‘Economy with Efficiency, Immigration Restriction to Reduce Unemployment, Old Age Pensions, “America First”’.25

During the 1932 presidential campaign, ‘America first’ briefly revived again – this time, swinging back to the Democrats. In a report on FDR’s presidential hopes, the New York Times mentioned his ‘progressive principles’, as well as ‘his unflinching stand for the interests of America first, as against the policy of helping Europe at the expense of American taxpayers’.26

Meanwhile William Randolph Hearst was actively campaigning on an ‘America first’ platform in 1932, having manufactured a presidential campaign for Democrat Speaker of the House John Nance Garner, in order to oppose the candidacies of Roosevelt and Al Smith, both of whom Hearst detested. He attacked them for their association with Woodrow Wilson, whom Hearst accused, somewhat forgetfully, of not being in favour of ‘America first’, despite the fact that Wilson was widely credited with having invented the phrase. As one 1930 article put it, ‘America first has become the property of the whole nation since Wilson first used it in a speech in New York in early 1915, but its misuse as a slogan by demagogic politicians has detracted sadly from its significance as a patriotic plea.’27

For Hearst, Garner’s opponents were ‘internationalists’ who had ‘fatuously followed Woodrow Wilson’s visionary politics of intermeddling in European conflicts and complications’. The American people needed to get ‘back upon the high road of Americanism’, Hearst maintained. ‘Unless we American citizens are willing to go on laboring indefinitely merely to provide loot for Europe, we should personally see to it that a man is elected to the Presidency this year whose guiding motto is “America first.”’28

Hearst’s campaign for Garner prompted outright derision from Walter Lippmann in his national column. ‘Mr. Hearst said with great fervor that Mr. Garner stood for America First,’ as if, Lippmann added, the other candidates stood for ‘America Second, Third or Fourth’. Garner’s opponents were ‘tainted’, Lippmann gathered,

by a common recognition that America’s security and welfare are in certain vital respects related to the security and welfare of other nations. They are ‘internationalists’ because they all believe that in the world today there are problems which have to be dealt with by international action. This, I take it, is what Mr. Hearst would like to deny.29

Sadly for Hearst, Garner had betrayed the great man’s trust by committing himself to internationalist policies. ‘This horrible experience ought to be a lesson to Mr. Hearst,’ Lippmann concluded. ‘It ought to teach him that there must be something the matter with his theories if nobody can stand by them.’30

Lippmann was not the only one to treat ‘America first’ with contempt. A Nebraska editorial, widely reprinted, suggested reconsidering its use as a motto. ‘The full extent of the perfidy behind the slogan through which the Republican party regained control of national affairs in 1918 and 1919 gradually is dawning upon the American people,’ it began, calling ‘America first’ the result of a ‘subtle and sinister attack planned and executed by a group of Republicans under the leadership of the late United States Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts’, an attack that appealed directly to xenophobia.

According to the editorial, Lodge deliberately popularised ‘America First’ because ‘he wanted to destroy Wilson’, and decided to exploit the fact that ‘inbred in the average Yankee [was] a deep aversion to Europe and the rest of the world. Out of this recognition was born the phrase, “America First.”’ The isolationism it led to represented ‘the real problem before President-elect Roosevelt. In some sections the cry of “America First” is heard still.’

‘We might as well be honest,’ the editorial finished. ‘We started it. We have heaped fuel on the flames for 12 years, until virtually we have closed the doors of trade the world over.’ If the United States had only followed Wilson’s dreams of internationalism, it would have averted much. Instead, America had been swayed by Republicans’ appeals ‘to ancient prejudices, carefully nursing instinctive suspicion’. It would take ‘stupendous sacrifice and Herculean effort’ for Americans to emerge from the ‘death valley’ of protectionist isolationism it had entered.31

The New York Times agreed. ‘The easiest way to get cheers is to wave the flag and shout for “America first,”’ it wrote at the beginning of 1932. Clearly Americans ‘are sick and tired of the company of the world’, while ‘the inconveniences of internationalism enrage every nation’. But this attitude could not last: the US was going to have to confront the international situation sooner or later, a reluctant, tacit realisation that had left Congress mired in ‘gloom’, ‘a sign that Washington at last faces facts. Worthy of a headline is this hopeful event: the official recognition of reality.’32

If enthusiasm for ‘America first’ was beginning, in some quarters, to wane, it was by no means dead. The New York State chairman of the Republican National Committee gave a speech just before Roosevelt’s inauguration in which he ‘expressed the hope that President-elect Roosevelt would dedicate himself to a policy of “America first”’.33

Roosevelt seemed perfectly prepared to use the slogan if it appealed to voters, although he never campaigned on the basis of it. In an article about interventionism headlined ‘Roosevelt Believes Public Backs “Sock in the Jaw” to Europe’, the New York Times reported ‘not only that [Roosevelt] is for “America first,” but knows what that means and how to enforce it’.34

‘America First Campaign Opens in Washington,’ read the headlines in the summer of 1933, a few months into Roosevelt’s first term. ‘US No Longer World’s Football,’ a Pennsylvania paper announced, although failing to specify when, exactly, America had been kicked around so badly by the international community. ‘A foreign policy based on the doctrine of “America First” was shaping up rapidly today as part of the “new deal,”’ it added, without asking what was new about America first.35

That summer a journalist reported that ‘America first is the slogan of our President’, apparently unaware that it had also been the slogan of each of the previous four presidents before him. ‘Let all of us take up the slogan,’ urged a Kentucky paper, ‘and in harmonious tones give it the power and volume it merits.’36 Readers might have been forgiven for thinking it had been given quite a lot of volume already.

That volume was continuing to diminish, however, as voices were raised in warning against isolationism, which merely created ‘emotional slogans and irrelevant catchwords’, contended one lecturer. With such easy slogans ‘demagogues could easily ensnare the votes of the yokelry’, from ‘William Randolph Hearst and his chain of newspapers’ to ‘“Big Bill” Thompson, [who] won the Chicago mayoralty election on a platform of “America First,” “Biff King George on the Snoot,” and “No World Court”’.37

Isolationism ‘reveals the emotional mysticism, the unshakeable irrationality, the almost unbelievable stupidity and provincialism of a large section of the American electorate’, the professor added bluntly, if tactlessly. Isolationism was simply a ‘popular patriotic mythology’ that seemed to cling to American culture like a fog.38

More laconically, a Delaware paper observed: ‘America first is a good slogan, but a more prosperous America is better.39

Another educator likened American isolationism on an international scale to individualism on a national scale. Domestically, ‘the unsound foundation of rugged individualism’ had simply resulted in inequality, giving more and more profits to ‘the few, the owners’, leaving the majority to low earning and purchasing power, while an increasing number had no earning power at all, and no chance to acquire it. The only way to get out of the mess America was in, at the nadir of the Great Depression, was to socialise ‘the vast resources’ of the nation, and distribute the wealth ‘to give to the whole public the earning and buying power essential to prosperity’.40

In terms of foreign policy, the teacher added for good measure, this individualism had expanded into an unworkable isolationism. ‘Nor can we continue to say: “America first, and the rest of the world go hang.”’41

One Ohio correspondent wrote to his local paper in protest against the position taken in a previously published letter signed by ‘A Republican’. ‘If the Republican party ever comes back or deserves to,’ he commented, ‘it will be by disavowing and discountenancing such deplorable partisan ideas.’ They had best reverse their old motto and ‘adopt the slogan “America first, the Republican party afterward,” for there are times in a nation’s life when unthinking partisanism is responsible for more sins than charity can cover’.42

* * *

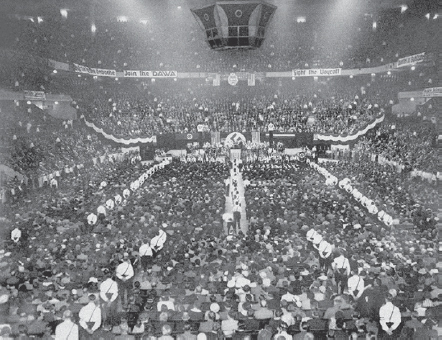

On 17 May 1934, 20,000 members of a group called the ‘Friends of New Germany’ held a rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City. The Friends of New Germany had been authorised by Rudolph Hess in 1933; officially recognised by Hitler, it was described by American papers as the ‘American subsidiary of the Nazi party’.43

They gathered that night, they said, in part to protest against a boycott of German goods. Such rallies were becoming more and more common; only a month earlier a correspondent had written to the New York Times to protest the mixing of ‘Stars and Stripes with Swastikas’ when both flags were hung together at meetings of the Friends of New Germany.

Newspapers did not give the American Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden that May much space. ‘Hitler Cheered at N.Y. Rally,’ read a small headline on page 4 of the Allentown Morning Call. ‘Chancellor Hitler was cheered and boycotters of German goods were booed tonight as 20,000 Nazi sympathizers packed Madison Square Garden in a rally under the watchful eye of hundreds of metropolitan police.’ There were also ‘eight hundred members of the German “Ordnungs Dienst”’ there to help ‘preserve order’.44 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle told its readers of clashes among protesters in the streets after the ‘Nazi rally’, putting the story on page 3.45 The Chicago Tribune called it a ‘demonstration’, relegating it to a few lines on page 6.46

The pictures taken that night in Madison Square Garden, however, suggest that more attention should have been paid; the New York Times reported it on the front page, reprinted a chilling photograph on page 3, mentioned it again the following day, and then never returned to the story again.47

Two months earlier, the German Consul General in New York had assured Americans that there were ‘only a few hundred national socialists in this country’.48 Ten days after 20,000 American Nazis gathered at Madison Square Garden, a welterweight boxing match there garnered more national coverage than the massive Nazi rally had. By the end of 1935, the Friends of New Germany would briefly dissolve – only to re-form almost instantly in early 1936, as the (ironically hyphenate) German-American Bund.

‘Americans, awake!’ wrote a correspondent to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle a few months after the rally. ‘Your indifference to this Nazi menace might result in almost anything’; the Friends of New Germany was ‘spreading Hitler doctrines in America under the cloak of Americanism’. The writer, self-proclaimed president of the ‘America First and Always Society’ of Brooklyn, was writing to ‘protest strenuously against those un-American methods of making bigots’ in America.49 But rejections of bigotry in the name of ‘America first’ were becoming harder and harder to find.

In September 1934 a man named James M. True founded ‘America First!, Inc.’, which promised to ‘give the New Deal an X-ray exposure’ and ‘restore the Constitution’.50 ‘America First, Inc.’ (variously printed with or without the exclamation point), would ‘combat and expose the propaganda and subversive activities originating within the New Deal’, reported the Scranton Republican.51 True’s charge that the Roosevelt administration had ‘Communist affiliations’ with Russia made it into newspapers around the country, including the New York Times.52 In October, America First, Inc. announced that credit unions were ‘tax spies’ who were being used in a federal surveillance system against American citizens.53 Then it alleged that ‘all Congressional candidates by the New Deal and the Federal Government have violated the Corrupt Practices Act of 1925’.54 True began giving speeches on behalf of America First, Inc., again claiming that Roosevelt’s administration was ‘controlled largely by Communists’.55

‘America First, Inc.’ had ‘succeeded in creating something of a stir’ that year, drily acknowledged one local paper, but only by ‘distorting the news’ with paranoid propaganda.56

That September, William Randolph Hearst visited Germany, where he met and ‘chatted intimately’ with Hitler.57 Many American papers, noting Hearst’s ‘sympathetic attitude toward the Nazi regime’, condemned his support of Hitler as ‘unfair, prejudiced and harmful’, the ‘worst kind of war-time propaganda’, a ‘direct appeal to prejudice, ignorance, and hatred’.58 These journalists did not think their job was merely to report the fact of Hearst’s visit; they had an obligation to make judgements and draw conclusions, calling out sophistries and bigotries where they saw them.

Asked to share his conversation with the German chancellor, Hearst replied that it was not for publication. ‘Visiting Hitler is like calling on the President of the United States,’ he said.59 Reporters did not hide their contempt at the idea of suggesting an American president could ever resemble a fascist.