The American dream was grabbing hold of the national conversation, but although Big Bill Thompson’s campaign had done much to bring ‘America first’ into disrepute, William Randolph Hearst and its other champions had no intention of relinquishing it without a fight.

On 29 January 1935, the Senate rejected a proposal that the United States join the Permanent Court of International Justice, otherwise known as the World Court, ambitions for which had long been referred to in the press as an ‘American dream of international justice’. The Senate’s vote was largely in response to a media campaign orchestrated by Hearst and Father Charles E. Coughlin, the influential and rabidly anti-Semitic spokesman for the ‘Christian Front’. The fight against the World Court had begun hard on the heels of the attack on the League of Nations, and its final defeat, a full fifteen years later, was nearly as consequential. In particular, Midwestern isolationists were held to have ended the measure; its defeat was pronounced another triumph for ‘America first’.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle responded with acid sarcasm in an editorial headlined ‘America First!’ At last, the leader began, ‘visionaries and “internationally-minded” folk’ who had been trying ‘to entangle us in foreign affairs’ had been vanquished. ‘We have been told a hundred times that this was a great victory for Americanism and that henceforth and forever we must put America first.’

The Eagle was ready, it promised; ‘duly contrite’, it would endeavour to get in line behind the new isolationism. Pledging itself ‘from now on to work unceasingly for the upbuilding of America, leaving the rest of the world more or less to shift for itself’, the editorial asked the prime question: ‘In what way can this newspaper promote the America First doctrine?’

If the best way to contribute to a stronger, more prosperous international order was to protect America first, then it followed that ‘we might contribute to this cause of a stronger, more prosperous America by doing what we can to advance the interests of Brooklyn. How can we best serve Brooklyn, now that we are done with internationalism and are determined to put America first?’

For a start, all the international shipping in New York would need to stop, so that Brooklynites were not forced to handle tainted foreign goods. This would save money, as neither a new subway system nor a new park on Jamaica Bay would now be required: once the international industries had disappeared, there would be plenty of room along the waterfront. That was fine, for clearly the docks, warehouses and factories that currently lined the harbour had no role in the new scheme of things; the government could also gradually phase out the Navy Yard, for ‘ultimately as a hermit kingdom the United States will not need a navy’. As there was no need for international trade, they could focus domestic activities in the Middle West, which was now dictating the nation’s interests.

‘The task of making Brooklyn over so that this community will conform to the America First program will not be easy,’ the column conceded. ‘The Federal Government must help if Brooklyn is to reach the new patriotic heights.’ It would have to build farm homesteads in the Midwest ‘to accommodate the two million people from this neighborhood who will have to move into the interior or starve’. And to conserve money, they should probably ‘put out the light on the Statue of Liberty’.1

Not everyone appreciated the ‘“smart aleck” editorial’, it should be said – and several people did so, including one who usually liked the Eagle’s columns, and for whom that ‘spleenful tirade [had] come therefore as a shock’.2

That the forces of ‘America first’ nativism were not going anywhere soon was made clear by letters such as the one sent to the Pittsburgh Press a month later. ‘Being an American, I believe in America first and that it takes one generation of people to make a good American citizen.’ Just the one was sufficient, evidently.

Therefore the correspondent was advocating ‘a law that would require all public officials in any capacity whatever to be a native-born American. It certainly hurts to try and transact business in any department of the City and County and come in contact with people of a foreign accent [sic] telling us how to run our government.’3 Nativism was nothing new, but by 1935 ‘America first’ had become the most obvious way to express it – to the point of arguing that being born in the United States naturally made you a better person.

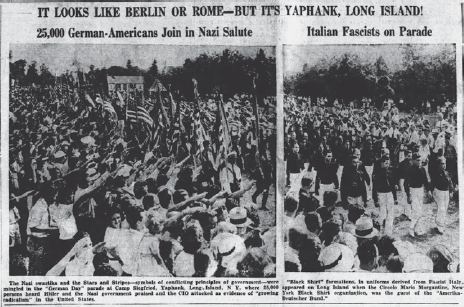

By August 1935, papers around the country were reporting that 5,000 members of the Friends of New Germany had gathered at Camp Siegfried, near Yaphank, Long Island, ‘to renew their allegiance to the political and economic creed of Nazi Germany.’ As part of the camp’s ‘summer festival’, they marched with Swastikas mixed with American flags, giving the Nazi salute; photographs circulated around the country.4

* * *

That September, a month after announcing he would run for president, Senator Huey Long was assassinated by the son-in-law of a political opponent. Called ‘America’s first dictator’ more than once, Long had worried many observers with his blend of populism and authoritarianism; after his death, profiles weighed his penchant for invoking the American dream against his predilection for American fascism.5

‘His promise of a house, a car, a radio, as well as $5,000 a year for all families, with education for deserving young people thrown in, sounded in the ears of many like a new version of the American Dream,’ noted one assessment soon after Long’s death.

What Long’s supporters did not at first see, the profile went on, was that ultimately he had chosen ‘fascism of the most rigid sort’ to solve the problems he had identified. That fascism was what Long had enabled ‘was sharply revealed in the blaze of guns in the corridor of the Capitol the other night’. Although the spaces were dedicated to democratic principles, ‘their spirit had fled’. Under Long, Louisiana’s government had become so ‘Balkanized’ that for the young doctor who killed him, ‘a Balkan solution’ – i.e. assassination – seemed the only alternative.

This was the true ‘menace of the Kingfish’, the profile concluded, using Long’s self-appointed nickname. His goal was not mere political gain. Instead, he was ‘an ambitious demagogue’, ‘who knew how to capitalize the discontent’ of various groups for his own advancement. Had Long lived, he might ‘have created an American Fascism. The moral of his career is that the United States is not of itself proof against fascism’, and unless democracy were safeguarded, fascism’s ‘head may rise again’.6

A biography of Long published a few weeks after his death was more succinct: ‘Kingfish may be the Mississippi valley rendering of Il Duce’.7

Despite many Americans’ assurance that ‘it can’t happen here’, the rise of Huey Long had shown worried observers just how it could. It was so clear that at the end of 1935 Sinclair Lewis published a novel with exactly that title, inspired by the career of Huey Long (but written before his assassination), in which he imagined what American fascism would look like. The title was ‘ironical’, Lewis told reporters. ‘I don’t say fascism will happen here,’ he added, ‘only that it could.’8

It Can’t Happen Here suggests that in America, fascism’s most dangerous supporters would always be those ‘who disowned the word “fascism” and preached enslavement to capitalism under the style of constitutional and traditional native American liberty’. American fascism would necessarily be shaped by capitalism – or, as Lewis all too prophetically put it, ‘government of the profits, by the profits, for the profits’.

A furious satire of the idea that American exceptionalism might insulate it from fascism, It Can’t Happen Here was one of Lewis’s most successful novels, attacking the ‘funny therapeutics’ of trying to ‘cure the evils of democracy by the evils of fascism’. Senator Buzz Windrip, obviously modelled on Huey Long, runs for president on a populist campaign of traditional values, making simplistic promises about returning prosperity (‘he advocated everyone’s getting rich by just voting to be rich’). A newspaper editor issues futile warnings: ‘People will think they’re electing him to create more economic security. Then watch the Terror!’

Once in office, Windrip makes good his authoritarian threats, creating a private security force called the Minute Men and imprisoning his political enemies in ‘concentration camps’, as Hitler had been doing in Germany since 1933.

When President Windrip is informed that resistance is beginning to foment – ‘bubbles from an almost boiling rebellion in the Middle West and Northwest, especially in Minnesota and the Dakotas, where agitators, some of them formerly of political influence, were demanding that their states secede … and form a cooperative (indeed almost Socialistic) commonwealth of their own’ – he rails at his cabinet: ‘You forget that I myself, personally, made a special radio address to that particular section of the country last week! And I got a wonderful reaction. The Middle Westerners are absolutely loyal to me. They appreciate what I’ve been trying to do!’

Windrip’s administration agrees to ‘hold all elements in the country together by that useful Patriotism which always appears upon threat of an outside attack’, and so they immediately ‘arrange to be insulted and menaced in a well-planned series of deplorable “incidents” on the Mexican border, and declare war on Mexico as soon as America showed that it was getting hot and patriotic enough’.

No longer did governments, Windrip’s cabinet understands, have to ‘merely let themselves slide into a war, thanking Providence for having provided a conflict as a febrifuge [remedy] against internal discontent’. Instead, ‘in this age of deliberate, planned propaganda, a really modern government like theirs must figure out what brand of war they had to sell and plan the selling-campaign consciously’, using modern advertising.

Windrip grows increasingly narcissistic, in love with his own cult of personality; he ‘amuses’ himself by shocking the country with his capricious, irresponsible acts. ‘Was he not supreme, was he not semi-divine, like a Roman emperor? Could he not defy all the muddy mob that he … had come to despise?’

A revolt begins – but then it stalls, because in America, ‘which had so warmly praised itself for its “widespread popular free education,” there had been so very little education, widespread, popular, free, or anything else, that most people did not know what they wanted – indeed knew about so few things to want at all’.

So they return to doing what Windrip tells them, and the novel ends with America’s third dictatorship in place, a false war with Mexico, a state-run media in which every newspaper is called ‘The Corporate’, and the resistance made up primarily of old reporters.

* * *

In October 1935, the same month that Lewis’s novel was published, another pro-Nazi rally was held at Madison Square Garden. Again, it garnered very little national coverage, most of which made it sound benign. ‘German Ambassador to the United States criticized the Versailles Treaty,’ reported the Cincinnati Enquirer, ‘in an address tonight before 15,000 German-Americans celebrating German Day in a mass meeting at Madison Square Garden.’9 And once again, photographs tell a rather more sinister story.

Sinclair Lewis and Dorothy Thompson had married in 1928; both his biographers and hers agree that his novel was primarily influenced by her circle’s conversation about the situation in Europe. As Lewis began writing It Can’t Happen Here, Thompson had just become the first American foreign correspondent to be ejected from Germany by Hitler, making her an international celebrity. ‘Whatever else the Hitler revolution may or may not be,’ she wrote, ‘it is an enormous mass flight from reality.’

In a letter, she commented that ‘most discouraging of all is not only the defenselessness of the liberals but their incredible (to me) docility. There are no martyrs for the cause of democracy.’10

Thompson returned home from Europe raging and worried. Within months, Lewis had finished his anti-fascist satire and soon after that Thompson was given a nationally syndicated column: ‘On the Record’ began in March 1936, positioned in the New York Herald Tribune opposite Walter Lippmann’s column, ‘Today and Tomorrow’, and it continued three times a week, for the next twenty-two years. Syndicated by more than 150 newspapers around the country, ‘On the Record’ was read by 10 million Americans; in the summer of 1936, Thompson was given her own national radio broadcast, which ran until 1938. By 1939, she had been named by Time magazine the second most influential woman in America, after Eleanor Roosevelt.

Two months after she began, in May 1936, Thompson published an ‘On the Record’ column titled ‘It Can Happen Here’, discussing the emergence of ‘bands’ of loosely organised fascists around America. A man from one group calling itself ‘Christian Vigilantes’ had sent her a letter sharing their ‘motto’: ‘Please learn by heart: Christian Nordic white America will, in the spirit of Hitler, keep the Jews and Negroes in their place of Jim Crow inferiority.’11

Several of these extremist groups appeared to have banded together into ‘a fantastic organization, running across state lines’, Thompson explained, of self-proclaimed ‘“white male Protestants,” pledged to “defend the United States and the Constitution”’. They were also determined ‘to exterminate Anarchists, Communists, Catholics, Negroes, and Jews; to restrict immigration and deport all undesirable aliens; to support and participate in lynch law; to arm its members for civil war … and eventually to establish a dictatorship in America’.

One of the organisation’s members had summarily shot another (in a fit of impatience, he said, not in a dispute) and the homicide investigation had uncovered the existence of this shadowy, underground affiliation. This band of far-right hate groups making common cause didn’t appear even to have a name.

‘Whom do they hate?’ Thompson asked. ‘Life, which has treated them badly. Who is to blame? Some scapegoat is to blame. The Negroes working in the fields that should be theirs? Or the Jews? Do they not keep the prosperous shops? Or the Communists … or the trade unionists … Or the Catholics who have a Pope in Rome? Or the foreigners who take the jobs? These are to blame. Therefore exterminate them. We are poor and dispossessed. But we are white, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant. Our fathers founded this country. It belongs to us.’ Protesting they were being replaced, they responded with violence.

These people, she noted, were ‘the poor, the credulous, the violent; little men, full of confused hatred. They are gullible. The organization, they are told, dates back to Revolutionary days. It has 13 officers representing the 13 original colonies. They have a direct link with the Ku-Klux Klan and its old night riders.’

J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI professed itself unable to pursue the group across state lines, while ‘states reserve to themselves, under the Constitution, the right to lynch their own minorities’. Thompson concluded by declaring that everyone who listened ‘tolerantly to intolerant expressions of racial prejudice, without registering our own indignation against such un-American ideas’ was equally to blame. ‘All of us who sit smugly by and think that It Can’t Happen Here!’12

Three weeks earlier, the Oakland Tribune had reprinted a poem called ‘America First’, written by thirteen-year-old Elaine Erickson.

It’s a startling final sentence, suggesting as it may that the poem is urging its readers to pay lip service to tolerance of other races, but all the while deep ‘down inside you think “America First” with me’ – as if by 1936, even children could see that ‘America first’ had become a code for secret racism.

In early 1936, James Waterman Wise, a popular author, lecturer and anti-fascist campaigner who was also the son of a nationally renowned rabbi, gave a series of talks on the probable characteristics of American fascism. At the John Reed Club in Indianapolis, he was reported to have included Father Coughlin in his description. (Father Coughlin delivered radio broadcasts that denounced ‘Jewish bankers’ and their cabbalistic control of world finance and media, ideas taken straight from the notoriously anti-Semitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.) Both Coughlin and William Randolph Hearst, Wise held, represented a distinctly American fascism, which, when it appeared, would ‘probably be “wrapped up in the American flag and heralded as a plea for liberty and preservation of the constitution”’.14

This famous image of a fascism camouflaged by the American flag (‘When fascism comes to America it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross’) would later be widely attributed to Sinclair Lewis (and indeed to It Can’t Happen Here) but Lewis never said it.

Instead, it probably came from Wise, who repeated the image in another lecture, from which he was quoted slightly differently: ‘There is an America which needs fascism,’ he said in this version. ‘The America of power and wealth’ depended on ‘enslaving the masses’ to endure. ‘Do not look for them to raise aloft the swastika,’ Wise warned, ‘or to employ any of the popular forms of Fascism’ from Europe. ‘The various colored shirt orders – the whole haberdashery brigade who play upon sectional prejudice – are sowing the seeds of Fascism. It may appear in the so-called patriotic orders, such as the American Legion and the Daughters of the American Revolution’ or ‘it may come wrapped in a flag or a Hearst newspaper’ – preaching ‘America first’.15

The ‘haberdashery brigade’ was a reference not only to the Blackshirts of Mussolini and the Brownshirts of Hitler, but also to the so-called ‘Silver Shirt Legion’, which had been formed in 1933 by William Dudley Pelley in Asheville, North Carolina. The Silver Shirts were an avowedly white supremacist, anti-Semitic, paramilitary organisation, and by 1936 just one of many groups declaring support for a fascist regime in America. That year Pelley ran on the presidential ballot as a candidate for the ‘Christian Party’ in Washington State, while rumours that he had called for ‘an American Hitler and pogroms’ were active enough to prompt the Hollywood League Against Nazism, headed by popular Jewish comedian Eddie Cantor, to send a telegram to President Roosevelt demanding an investigation into Pelley’s ‘secret pro-Nazi organization’.16

It was just weeks after Wise’s lectures that Fritz Kuhn, who had fought in the Bavarian infantry in the First World War and become an American citizen in 1934, formed the German-American Bund. Within months, a ‘Union Party’ assembled to unite the right, creating an affiliation of white supremacist fascist organisations.

Dorothy Thompson went after them all in the summer of 1936 in a two-part column called ‘The Lunatic Fringe’. The Union Party represented, Thompson charged, ‘a nearer approach to a national fascist tendency’ than anything yet seen in America. ‘The Union party says America shall be self-contained and self-sustained’, attacking ‘the moneyed interests of Wall Street’, as well as the ‘“reactionaries, socialists, communists, and radicals,” but they reserve their greatest vituperation for advanced liberalism which they lump with socialism’.

Thompson was distinctly unimpressed by those conflating liberalism with socialism. ‘So’, she remarked, ‘did Mr. Hitler.’

Their followers, too, resembled the followers of Nazis: ‘the dispossessed and humiliated of the middle classes, bankrupt farmers, cracker-box radicals, and the “respectable” but extremely discontented provincials’.

And because of the group’s opposition to all forms of socialism, ‘powerful industrial and conservative interests would secretly support them, and certainly tolerate them, in the hope of bringing down a program like that of President Roosevelt’, the New Deal’s social welfare system. Some conservatives and capitalists, she warned, would make cynical alliances with fascism rather than tolerate liberalism.

‘The combination of monetary radicalism, plus hundred percentism and hatred of so-called alien ideas, plus the belief in the capitalistic system of production,’ she went on, ‘were all characteristic of the Nazi movement before it came into power. And anti-socialist and anti-liberal, scripture-quoting and anti-alien leadership, which makes its appeal not to the well-to-do, but to the discontented and indebted lower middle classes,’ as well as to the ‘incredibly numerous’ ‘so-called patriotic groups of Ku Klux Klan mentality’. Whether such a group could consolidate power would depend in part on whether a leader emerged who could catalyse these movements.

And it would depend, too, she added, ‘on how enlightened American conservatives prove themselves to be’, how willing they were to fight such a leader. If extremist groups formed on both the left and the right, as they had in nearly all European countries, ‘and men who call themselves conservatives’ began helping far-right groups in order to defeat liberals, ‘then we will be well started on the road over which much of Europe has gone’, namely, the road to fascism.17

In the follow-up column, ‘The Lunatic Fringe II: “Saviors of Our Race and Culture”’, Thompson listed dozens of anti-Semitic, pro-fascist fringe organisations in the United States, including not only the Silver Shirts, but also the ‘Crusader White Shirts’, the Black Legion, the ‘World Alliance Against Jewish Aggressiveness’, any number of ‘Christian’ organisations (‘Loyal Aryan Christians’, the ‘Defenders of the Christian Faith’) and the Ku Klux Klan, all busily circulating The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and denouncing Roosevelt as ‘Rosenfeld’.

But because people on the far left ‘stupidly reply in kind, and label everybody who does not agree with them “Fascists”’, left and right had combined to make ‘the very word “patriotic” anathema to any upright and generous mind’. Invoking Samuel Johnson’s famous quip about patriotism, Thompson charged: ‘It is time for patriots to insist that patriotism is not the last refuge of a scoundrel, nor the monopoly of the ignorant, prejudiced and fanatic.’18

While it is true that not all those who disagreed with the hard left were fascists, it is also true that there were Americans prepared to make common cause with fascism while insisting they weren’t fascists, ready to ‘tolerate’ it, as Thompson had observed in her previous column, to achieve their own political ends. Fellow travellers don’t have to be the ones doing the navigating to end up in the same place.

That year William Faulkner published Absalom, Absalom!, his great meditation on the processes of mythmaking and how they intersect with national history, a Homeric epic of America that shakes off dreams of moonlight and magnolia to reveal the Gothic nightmare underneath. The plot of Absalom is driven by the proposition that what had defined Southern history was the fact that poor white people gained self-respect and racial pride from their belief in their inherent superiority to black people. If that sense of racial superiority were ever threatened, the story recognised, they would erupt in violence.

Just a year earlier, W. E. B. Du Bois had similarly identified the ‘psychological wage’ of whiteness, the recognition that ‘white laborers were convinced that the degradation of Negro labor was more fundamental than the uplift of white labor’. Race had functioned to divide and conquer the workers, endlessly deferring revolution. (Many would argue, following Du Bois, that the question of why socialism never took firm hold in America can be answered in one word: race.) Although white labourers remained poor, Du Bois added, they were ‘compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage’, the wage of racial superiority.19

The past isn’t dead, Faulkner famously said. It isn’t even the past.

* * *

Meanwhile, ‘America First, Inc.’ was making some more noise. Time magazine picked up a story that had first appeared in the radical magazine New Masses, reporting that America First, Inc.’s founder, James M. True, told a journalist (who was pretending to be a Republican) that he was planning a ‘national Jew shoot’ in September.20 True also boasted that he had patented (under the category ‘Amusement Devices and Games’) a policeman’s club, which he referred to as a ‘Kike Killer’, two examples of which were sitting on his desk. Since ‘for a first-class massacre more than a truncheon is needed’, True was practising for his ‘September pogrom’ by shooting at soap, as ‘the consistency of soap approximates Jewish flesh’.21

The Time journalist’s tone in reporting all this seemed rather flippant. Four days later the Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, sounding considerably less amused, named ‘America First, Inc.’ one of the country’s ‘leading anti-Semitic organizations’.22

In February 1937, Roosevelt made what many consider the greatest political mistake of his career, trying to expand the Supreme Court in order to counter its continued hostility to many of his New Deal reforms. Widely denounced at the time as an assault on the principle of the separation of powers in US government, Roosevelt’s attempt to ‘pack’ the Supreme Court was strongly opposed by even his own vice president.

Across the nation, editorials called the president a ‘dictator’. Dorothy Thompson, often a sharp critic of Roosevelt, warned that this was just how a Hitler would come to America. After some desultory resistance, ‘the American people, who are seldom interested in anything for more than two weeks, will begin to say, “Oh, let the president do what he likes. He’s a good guy.”’ Unfortunately, ‘no people ever recognize their dictator in advance. He never stands for election on the platform of dictatorship.’

‘When Americans think of dictators they always think of some foreign model,’ she added, but as all dictators claim to represent ‘the national will’, an American dictator would be ‘one of the boys, and he will stand for everything traditionally American’. And the American people ‘will greet him with one great big, universal, democratic, sheeplike bleat of “O.K., Chief! Fix it like you wanna, Chief!”’23

In July 1937, the Bund established Camp Nordland, in Andover, New Jersey, where Kuhn told an audience of 12,000 that the organisation stood ‘for American principles, America for Americans’.24

On 4 July, standing before a giant swastika, Kuhn addressed an audience of 10,000 at Camp Siegfried, Long Island, promising that the Bund, ‘which professes to be 100 per cent American’, would ‘save America for white-Americans’.25 Photographs were carried from coast to coast of ‘Fuehrer Fritz Kuhn’s uniformed “one hundred per cent Americans’’’, some 25,000 strong, saluting Nazi and American flags on Long Island and in New Jersey, provoking outcries around the country.26

When a senator from Alabama named Hugo Black was nominated for the Supreme Court in the summer of 1937, questions were raised about his prior associations with the Klan. The confirmation committee was urged to inquire ‘into the facts and implications of Senator Black’s endorsement by the Ku Klux Klan at an earlier period of his career; into his silence as a political leader in Alabama on the issues raised by the Scottsboro case; into his attitude during the Hoover Administration toward equality of relief between white and colored victims of unemployment; and, above all, into his reported threat to filibuster against anti-lynching legislation’.27

A month later, Black was easily confirmed as a Supreme Court Justice. Just after his confirmation, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette ran a week-long exposé, disclosing Alabama Klan records showing Black had become a lifelong member in 1926. Locals ‘talk of the great days when the Klan ruled Alabama and Hugo Black journeyed up and down the state preaching the glories of the Invisible Empire’. A local Klansmen spoke to reporters, declaring, ‘I am proud to be known as a Klansman.’ That immense pride notwithstanding, he asked the reporter to withhold his name, before explaining that everyone knew Black owed first his Senate seat, and then his seat on the bench, to the Klan.28

In October, Black gave a radio address admitting to having been a Klansman, but claimed that he had resigned and repudiated his membership, and had had nothing to do with the Klan as a senator. Editorials around the country exploded in response, denouncing Black’s ‘confession’ as ‘a mess of factitiousness and inconsistency’. The Baltimore Evening Sun observed that ‘since Hugo L. Black was a Southern politician of the cheaper sort, it was almost inevitable that he should have joined the Ku Klux Klan’. But as ‘the fact that it was a racket became more and more apparent’, ‘even the most backward politicians could see the writing on the wall and publicly denied any connection with it’. Black differed from these only because he ‘didn’t see fit either to admit membership or to denounce the objectives of the Klan until public pressure forced him to do so’. A Virginia leader was equally biting. ‘His repudiation of the poisonous Klan philosophies now does not wipe out the unwholesome record of the silence that was broken only after public clamor had become so great that he was compelled to break it.’29

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette remained firmly unconvinced, reporting the words Black used in accepting his Senate nomination before the Klan, whom he called at the time ‘representatives of the real Anglo-Saxon sentiment that must and will control the destinies of the Stars and Stripes’. Regardless of whether he had repudiated his former values, the editorial protested, ‘no man with that record ought ever to sit upon the highest court in the United States of America’.30

Dorothy Thompson wrote several furious columns denouncing Black’s appointment; in one, she imagined Senator Black cross-examining Justice Black about his Klan associations.

But Thompson was equally enraged by Black’s partisan defenders. Because he was a Democrat appointee, progressives were justifying his record. She excoriated ‘so-called liberals’ who would not only ‘stoop to making an apology for the Klan, but actually to justify any kind of personal behavior, if it is politically expedient’. Such amoral rationalisations meant abandoning ‘the ground upon which you can attack most of the evil in the world’, from ‘the third degree in American police stations, to concentration camps in Germany and wholesale executions in Russia’. Moreover, she warned: ‘If political expediency alone is to be the guide of men’s conduct, it follows that politicians in the future will be justified in using the Klan, or any similar organization, as an instrument of political power. Do the “liberals” want to be responsible for a revival of the Klan and all its kindred organizations, such as the Black Legion and the Nazi organizations, on this soil?’

The Klan had already been revived once, she noted, transforming itself in the 1920s into ‘a money-making racket for the men at the top, playing upon the prejudices of the ignorant’. Now, thanks to Black’s confirmation and liberals’ decision to defend it, the Klan ‘can, and will, say to thousands of the same kind of men who joined it before, that the President appointed Mr. Black to the Supreme Court because he was a Klansman, and that the administration is behind the Klan’.

The Klan, she pointed out, was also a firm believer in ‘political expediency’.32 The example set by political leaders had enormous consequences for the nation; cynical justifications for immoral behaviour would seep down and poison the political system.

A sardonic joke began circulating in Washington: Justice Black wouldn’t have to buy a new robe when he joined the bench, they said. He could just dye his white one black.

* * *

Meanwhile, the German-American Bund was holding rallies and picnics on the West Coast, as well. In Los Angeles the News of the World (‘A Journal in Defense of American Democracy’) revealed that for German Day in 1937 fascists had gathered for a ‘Nazi-run picnic’ in what was then called Hindenburg Park, the site of more than one American Nazi rally in the 1930s.33

Books began appearing that explained German fascism to American readers. One called The Spirit and Structure of German Fascism chronicled ‘the most impressive contemporary experiment in social retrogression, an experiment frequently described as “industry feudalism”’. Robert A. Brady argued that fascism was ‘the last stand of capitalism against its own inherent destructive forces’, the ‘“corporate state” a final effort to insure the continuance of profits’. This was accomplished by means of ‘a reorientation of popular beliefs and ideals, a tremendous emotional wave of personal loyalty to the fascist leader, and the whole counterfeit system of “blood-and-soil” mysticism’.34

That autumn a South Carolina paper shared a striking image of a crowd watching a parade on the far Upper East Side of Manhattan. ‘Some Cheer, Others Hold Noses as Nazis Parade,’ read the headline, and a caption added further bite: ‘Here is a view of some of the spectators who watched the parade of the German-American Bund, Nazi organization in America, in New York’s Yorkville. Less than a thousand marched in the parade, after publicity given by the Bund had placed the figure at ten times that number. Note that some of the bystanders are giving the Nazi salute, while others are delivering the Bronx Heil, or razzberry. Maybe they just don’t like Nazis?’35

Two months earlier, Roosevelt had given a press conference pledging to do everything possible to ‘keep us out of war’; soon after, Hitler and Mussolini appeared together at a rally in Berlin. Their speeches were broadcast around the world, as Hitler affirmed ‘the common ideals and interests inspiring Italy and Germany’. A week later, Roosevelt delivered his so-called ‘Quarantine Speech’, trying to shift America out of its determined isolationism, declaring that ‘peace-loving nations must make a concerted effort to uphold laws and principles on which alone peace can rest secure’, for fascism was creating ‘a state of international anarchy and instability from which there is no escape through mere isolation or neutrality’. But Roosevelt’s court-packing attempt had wasted nearly all of his political capital; Americans were listening to the isolationists, who insisted that FDR was trying for political reasons to force America into a foreign conflict.

In March 1938, the Nazis marched into Austria. A few weeks before the Anschluss, Thompson had written, in a column called ‘Who Loves Liberty?’: ‘The very essence of American democracy is the protection of certain basic rights of individuals, groups and minorities against a majority of even 99 per cent.’

‘Perhaps it is a personal prejudice,’ she added, ‘but I happen to dislike intensely “liberal” Fascists, reactionary Fascists, labor Fascists, industrial Fascists, Jewish Fascists, Catholic Fascists, and personal Fascists. When it comes to choosing the particular brand of Fascism, I’m not taking any.’36

America was certainly offering plenty to choose from. That spring, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that William Dudley Pelley, head of the Silver Shirts, had recently painted ‘an idyllic picture’ of a meeting with James M. True, founder of ‘America First!, Inc.’, when they sat in ‘comfortable chairs in the city of Washington, DC, and talked of many things that are good for the soul’, such as their mutual determination to wipe out the Jews. True had ‘a glint in his eye’, Pelley rhapsodised, ‘that means humor or battle, depending on your racial extraction, whether you’re Gentile or Jew’.

As the Daily Eagle noted, True was ‘not only anti-Semitic but anti-Roosevelt and anti-New Deal, pro-Japanese, pro-Nazi and pro-Fascist everywhere and even pro-Moslem [sic]’. According to ‘the William Dudley Pelleys and the other native little American Hitlers’, the journalist added, ‘true Americanism’ could only be ‘based on distinctions of race, color, and religion. They talk, though guardedly, of “bloodshed” to bring these things into being. “Patriotism” consists of plotting, though ineffectually, for the overturn of the government.’37

Later that year, a Yale professor named Halford E. Luccock delivered a lecture, picked up by the New York Times, that gave voice to a sentiment increasingly expressed. ‘When and if fascism comes to America it will not be labeled “made in Germany”; it will not be marked with a swastika; it will not even be called fascism; it will be called, of course, “Americanism.”’ He added: ‘the high-sounding phrase “the American way” will be used by interested groups, intent on profit, to cover a multitude of sins against the American and Christian tradition, such sins as lawless violence, tear gas and shotguns, denial of civil liberties.’38

It wasn’t a stretch – the simple fact, as we have seen, was that many Americans had long been associating ‘pure Americanism’ with bigotry, nativism, xenophobia and racial violence.

That autumn, reports grew of ‘a “rising tide of anti-Semitism” in the United States’, which seemed at least partly due to ‘the large number of organizations in this country which agitate such sentiments and in part on the effects of “the situation in Europe”’, noted the New York Times. Those prominent anti-Semitic organisations included ‘America First, Inc.’, along with ‘American Aryan Folk’, the ‘American Gentile Protective Association’ and ‘American Fascists’.39

At the same time, William Randolph Hearst decided to put his considerable weight behind ‘America first’ once again, delivering a radio broadcast responding to Winston Churchill’s request that the United States ‘join forces with Europe’s democracies’. Hearst insisted that ‘America must not be drawn by unwarranted sentiment into the disasters of another foreign war’. The slogan ‘America First Should Be Every American’s Motto’ now appeared on the masthead of all Hearst papers.40

That year the legal philosopher Jerome Frank published Save America First: How to Make Our Democracy Work, which was much in the news, arguing that isolationism was the only defence for American democracy and prosperity; to steer a course between communism and fascism, the ‘profit system’ of capitalism had to be saved.

Suddenly ‘America first’ was right back at the forefront of the national conversation, as Americans once more signed letters to their local papers ‘America First’, and editorials joined in, urging isolationism in its name. A Pennsylvania leader headed ‘America First’ endorsed the advice of an American Legion spokesman, who said ‘that citizens of the United States would be “saps” if they embarked on a European war for the sake of England and France’.

The editorial wholeheartedly concurred: ‘We have no place in these United States for Nazism, Fascism, or Communism. What we want, unadulterated by any foreign ideology, is Americanism.’ Americans needed to ‘guard the precious liberties we enjoy and improve our own lot while Europeans solve their own problems’.41 What they didn’t do was acknowledge the rising threat of ‘one hundred per cent American’ fascism in the shape of the Bund and other self-proclaimed American fascist groups.

A South Dakota paper, also headlined an editorial in praise of ‘America First’: ‘It is hardly short of axiomatic that our national interests will be made more secure if we maintain a program of serving America first … It is practical sense to serve America first, and to keep out of foreign crises in which we are interested secondarily to our own security and well-being.’42

At a rally of the Bund in Queens in November 1938, Fritz Kuhn told his audience that Roosevelt’s administration was offering not a New Deal, but a ‘Jew Deal’. ‘The Bund leader declared the American press and radio were controlled by Jews “who are trying to smash this country even as they tried to ruin Germany”,’ reported papers around America.43

That same day the American press also widely circulated a story about an inquiry being undertaken by ‘the house committee investigating un-American activities’ into the alarming increase in far-right, pro-fascist organisations. The chairman of the committee identified a long list of such groups, including ‘America First, Inc.’ in Washington, DC, as well as the ‘American Aryan Folk Association’ (Portland, Oregon), ‘American Fascist Order of Black Shirts’ (Atlanta), ‘American Fascists’ (Chattanooga, Tennessee), ‘American Fascist Khaki Shirts of America’ (Philadelphia), ‘National Socialist Party’ (New York), ‘American Nationalists’ (Washington, DC), ‘American White Guard’ (Los Angeles), ‘Black Legion’ (Detroit), ‘Black Shirts’ (Tacoma, Washington) and many others.44

On 30 September 1938, Neville Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement trying to appease Hitler, who was so very appeased he promptly marched into Sudetenland and Czechoslovakia. Less than six weeks later, on the ‘night of broken glass’, Nazis and their sympathisers destroyed Jewish businesses, razed synagogues, arrested thousands and killed almost a hundred Jewish people. The excuse for Kristallnacht was the assassination of a German official in Paris by a young Jewish Pole, a refugee named Herschel Grynszpan.

Dorothy Thompson was outraged, writing passionate accounts of Grynszpan’s desperation, describing the refugee crisis and raising money for his defence. In ‘The Nature of “The Thing”’, written a few days later, she warned America again. (Thompson was called an ‘American Cassandra’ more than once; she retorted that history always proved Cassandra correct.)

Part of the problem in the United States, Thompson observed, was that a certain type of ‘industrialist leader’ showed ‘a natural subconscious affinity for what is presented to them as the concept of the Fascist state’. They were falling for what a later generation would call spin, which made fascism appear ‘familiar and comfortable to them. It is – in the propaganda designed for industrialists – a large, efficient, monopolistic corporation, run by an efficient management.’45

European fascism was undeniably corporatist in certain respects, she explained: ‘that is why Henry Ford likes Nazism, for which sympathy he has recently been decorated by the Nazi state. Nazism, in Mr. Ford’s mind, is a Ford factory on a gigantic scale’, one that ‘has gotten rid of the “parasitic” Jews’.

But this airbrushed image of corporate fascism was a myth. In actuality Nazi leaders were not industrialists, but ‘ruthless, third-rate, psychopathic, déclassé formerly unemployed intellectuals and soldiers’. Fascism whipped up mass support by ‘a combination of propaganda and terror’. To do this it had to keep the masses ‘aggressive – by working up continual internal and external enemies’, posing as the people’s ‘defender against all the forces of privilege, against the richer nations and the richer classes’.

For democracy to defeat fascism, it would have to see clearly what it was fighting. It would need to create ‘passionate solidarity for the things we all agree on’. And it would need to ‘regard as treason any attempt to make one American detest another American on racial grounds’.46

Thompson was hardly the only fierce critic of fascism in the United States, of course. But thanks to her prominence, forcefulness and outspokenness, it is also true that for many Americans she was rapidly becoming the voice of the anti-fascist cause in the United States. ‘It would scarcely be possible to exaggerate,’ her biographer later observed, ‘the extent to which she had become identified in the public mind with the struggle to preserve democracy.’47

* * *

In the first days of 1939, a flurry of reports appeared concerning Nazi intentions for the Bund. A story disclosing that ‘German officials plan to create a “strictly American division” of the German-American bund’ was reprinted around the country; the new division would entail the ‘merger of a number of minor subversive forces’ in America ‘under the swastika leadership’ of the Bund.48 A separate item noting that ‘about 25,000 persons are active members of the German-American bunds’ was also widely reprinted on the same day, adding that ‘about 100,000 persons are “willing to be seen” at public bund manifestations’.49

Throughout 1939, Dorothy Thompson continued to fulminate against the ‘machine of Nazism’, ‘the strange rag-bag of nazi ideology’.50 They were ‘propagandists who have nothing even to propagate’, ‘revolutionists without a revolutionary idea; ideologists without an ideology’.51 ‘If Hitlerism spreads it is only because the peoples who already have all imaginable resources don’t know what to do with them. They continue to cherish nationalism and to increase it, even as between each other, and to keep the world Balkanized as a matter of principle.’52

But Americans increasingly responded to a Balkanized world with cries of ‘America first’. Letter writers insisted that the ‘persecutions’ in Europe were not America’s problems: ‘the sooner our American diplomats adopt the policy of “America First” the better off our grand country will be. It certainly doesn’t make sense to me how any full blooded American can get riled up over the foreign persecutions.’53

Politicians once again began arguing that America should ‘mind our own business and keep out of other peoples’ troubles and other peoples’ wars … A sound “America First” foreign policy is the best of all defenses.’54 Senator Rush Holt of West Virginia gave a radio address entitled ‘Let’s Look After America First’: ‘to become entangled in the controversies of foreign countries is a sure way to endanger our country’.55

On 20 February 1939, four days after Senator Holt’s broadcast, the Bund held a rally of 20,000 supporters in Madison Square Garden, where they stood ‘under the sign of the swastika to denounce “international Jewry,” some members of the Roosevelt cabinet, and any American alliance with European democracies’, as ‘uniformed storm troopers marched intermittently inside the Garden’.56

A young Jewish hotel worker jumped on the stage to protest; he was beaten and kicked by Bund storm troopers before the New York police, on hand to maintain order, rescued him. The event was filmed and photographs circulated widely; large swastikas hung above the stage, while storm troopers in Nazi uniform (except for their white shirts) were lined up at attention in every aisle.

‘Stop Jewish Domination of Christian Americans,’ read one enormous banner, while papers reported that the stage was ‘decorated with a gigantic picture of George Washington, standing between a mélange of American flags and Nazi swastikas’.57

Dorothy Thompson attended the rally to draw attention to it, loudly laughing and shouting ‘Bunk!’ and ‘Stupid fools!’ during the speeches (one of which jeered, as per, at ‘President Franklin Rosenfeld’).58 When the Bund’s storm troopers tried to remove her, she asserted her rights and promptly returned to the front row. Papers around the country shared with delight Thompson’s ‘eloquent rebuttal’ of the fascist leaders’ speeches: ‘Bunk!’59 (The Chillicothe Gazette declined to print the word ‘bunk’, primly reporting that she shouted ‘nonsense!’)60 ‘Dorothy Thompson in Gala Fight,’ read one front-page headline, jokily comparing her appearance to a prizefight.61 ‘Writer Given Rush by Nazis at Bund Meet,’ reported another.62

Thompson responded directly to the Madison Square Garden rally in her next column. An open alliance had been formed, she explained, ‘between the followers of Father Coughlin and the followers of Fritz Kuhn to abolish the American democracy’. Their alliance became plain at ‘the meeting in the Madison Square Garden called by the German-American Bund under the slogan of “Free America”’. The previous day, Father Coughlin had distributed promotional materials and tickets for the rally at one of his own meetings. ‘They enjoy the prerogatives of free speech, and with the instruments of democracy they intend to set up in this country a Fascist regime.’

‘They do not, of course, call it Fascist,’ she continued. ‘Sinclair Lewis, when he wrote “It Can’t Happen Here,” foresaw with prophetic vision that when Fascism came to America it would present itself as “true Americanism.”’

In the novel, she noted, Lewis had predicted ‘almost exactly the meeting that was conducted in Madison Square Garden Monday night’, at which there would be ‘Storm Troopers’ in place ‘to deal with “unruly elements.” Those unruly elements are you and I,’ she added.

Thompson would continue to be defiantly unruly in her spirited defences of democracy. Sharing quotations from speeches on the night, she told her readers that one Lutheran minister from Philadelphia had ‘admitted the movement was Fascist’, when he informed his audience: ‘There is no line to be drawn between democracy and fascism. It is between communism and fascism. There is no in-between.’63 Democracy was not an option in the Bund’s version of ‘one hundred per cent Americanism’.

* * *

On 13 May 1939, the ocean liner St. Louis set sail from Hamburg, Germany, with 937 passengers on board. Nearly all of them were Jews fleeing the Holocaust; most were Germans; a few were stateless. They were en route to Havana, Cuba, hoping eventually to find safe harbour in the United States, where many of them had applied for entry visas. None of the passengers knew that, just as they sailed, Cuba had invalidated most of their landing certificates. Cuba would only allow twenty-eight passengers to disembark when they arrived on 27 May, twenty-two of whom were Jewish and already held US visas. The other six were Spanish and Cuban, and had entry papers. One passenger attempted to commit suicide and was hospitalised. The rest continued to hope for US visas.

But they did not receive American papers, and Cuba would not receive the refugees, ordering them to depart Cuban waters. With nowhere else to go, they set sail for Florida, and when they were near enough to see the lights of Miami passengers sent telegrams to the president, pleading with him to let them enter. Roosevelt did not respond. A State Department official sent a cable informing the refugees they would have to get on a waiting list with everyone else.

The 1924 Johnson–Reed anti-immigration laws were still in force, and the quotas for German immigrants had long been filled; nor did Roosevelt’s administration invoke the special measures necessary to override them. The St. Louis was forced to return to Europe, where eventually the refugees were distributed among Britain, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Half survived the Holocaust; the other half perished.

The St. Louis was far from the only ship of Jewish refugees to be turned away from the Americas and forced to return to Europe, but it became the most infamous, symbolising the plight of so many stranded, imperilled people. In a grim little historical irony, twelve years after the Spirit of St. Louis had bridged the distance between the United States and Europe, the spirit of St Louis had become decidedly less unifying – a divisiveness that would soon be voiced by none other than the pilot of the Spirit of St. Louis himself, Charles Lindbergh, who was about to make his own isolationist views widely known.

Before Lindbergh spoke up, however, yet another callous spirit was evinced on behalf of St Louis. In August 1939, a letter was sent to the St. Louis Star and Times urging the US to turn away 20,000 refugee children in the name of ‘America First’: ‘I agree with “American”,’ a previous correspondent, it began. ‘How can we take care of 20,000 refugee children when we can’t take care of our own poor and needy?’

Disputing another previous correspondent, the anonymous writer added: ‘“Humanitarian” says the United States was once known for its kindness and friendliness to refugees, which is true, but why shouldn’t we help our own people first? Bringing in 20,000 refugees to add to those who already have entered will only make it that much harder for our own children to get work later on. – America First.’64

‘Uncle Sam was the goat for England and France in the last war,’ wrote a citizen of Rochester, New York. ‘Let England and France stand on their own feet and not hide behind the Stars and Stripes. America first, last, and always.’65 A correspondent from Alabama had the virtue, at least, of honesty: ‘“America first” may sound selfish, but it is a pretty good slogan in a selfish world,’ he contended; the justification was reprinted around the country.66

Editorials also conceded selfishness in order to extenuate it. ‘We, too, think selfishly. We think: “America First!”,’ announced the Miami News, rejecting ‘foreign entanglement’. ‘America is civilization’s rear guard, its reserve. It serves best by strengthening those whom a less happy fortune has placed in the battle front. Never again an army abroad! England stands for England first, France for France first. We strengthen England or France only if that serves America first. Don’t be sentimental. America first!’67

By the end of the year, Congress had passed its fourth Neutrality Act since 1935. When the 1939 Neutrality Act was debated, isolationists once again argued that ‘we of America owe a responsibility: to America first’.68

Observers began to point out that America first isolationism was difficult to distinguish from Hitler’s German nationalism (just as comparisons between ‘America first’ and ‘Deutschland über Alles’ had noted twenty years earlier). A Hawaii editorial compared it to Mein Kampf, noting that Hitler had written: ‘The National Socialist movement does not want to be the defender of other nations, but the champion Vorkaempfer of its own nation – this means that National Socialism is not the champion of the general idea of nationalism, or of some right belonging to other nations or races; it serves only its own nationalism and its own rights.’ This echoed, stated the leader, ‘to a degree, our own isolationists … It is quite outspoken in the slogan, “America First.”’69

Increasingly, they also recognised the association of isolationism with the rise of pro-fascist organisations, many of which claimed ‘America first’ as their slogans. A Cincinnati editorial titled ‘An Ugly Picture Unfolds’, reprinted around the country, believed it ‘genuinely disturbing’ how many extreme right-wing organisations were gathering in the United States: ‘the Bund, the Silver Shirts, the Knights of the White something-or-other, America First, Incorporated – these and many other rackets preying on ignorance and intolerance have ceased to be mere shell games designed to part yokels from their money. They have become an intrenched [sic] bloc serving the common end of destroying democracy and supplanting it with a tyranny which they will not call Fascism until it succeeds. All, of course, are “patriotic” and “Christian”!’70

On 1 September 1939, Hitler invaded Poland. Two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany, and the Second World War commenced. Three days after war began in Europe, Dorothy Thompson let her exasperation sound in a radio broadcast. ‘I think it is one of the most incredible stories in history, that a man could sit down and write in advance’ – in Mein Kampf – ‘exactly what he intended to do; and then, step by step, begin to put his plan into operation. And that the statesmen of the world should continue to say to themselves: “He doesn’t really mean it! It doesn’t make sense!”’71