It was during the Second World War that the long-standing, implicit friction between the principles of ‘America first’ nativist isolationism, and the ‘American dream’ of tolerance and equality, finally ignited into open conflict. And they did so in part due to the intervention of Charles Lindbergh, spokesman for the most famous iteration of all the various America first movements, which would become known as the America First Committee.

Two weeks after Germany invaded Poland, Lindbergh delivered his first national radio broadcast. Over the next two years, in a series of speeches, essays and broadcasts, he urged the United States to stay out of the conflict. Instead of fighting in Europe, he argued, America should defend – and dominate – the Western Hemisphere.

After the kidnapping and murder of their infant son, Lindbergh and his wife Anne had fled the American media circus that ensued in 1935. While living in England and then in France, they travelled throughout Europe, including several trips to Germany at the invitation of the Nazis, to survey German air power. The transparency of Hitler’s attempts to use Lindbergh to intimidate the United States was obvious to many, but not, apparently, to Lindbergh, who was duly impressed by his few, carefully staged – and, history would show, carefully misleading – visits. Lindbergh accepted the Distinguished Service Cross of the German Eagle from Hermann Goering, Hitler’s second in command, in 1938.

Isolationism was one thing, accepting a Nazi medal quite another. The decision was widely denounced in the American press, which raised sharp questions about Lindbergh’s loyalty, even accusing him directly of being a Nazi sympathiser. The ‘charitable explanation’, wrote an Alabama editorial in typical terms, would assume that Lindbergh was ‘much embarrassed by the honor’. But ‘it seemed like a betrayal of our own country’s best European friends … It was as if he had been going around Europe getting confidential knowledge of military aviation in the various countries and then using it for the benefit of the Nazis.’ If Lindbergh had been ‘misrepresented’, the item added, ‘he should take the trouble to explain publicly’.1 He didn’t.

A year later, as the blitzkrieg was exploding across Europe, Lindbergh began a series of radio broadcasts urging America not to take arms against Hitler, insisting that Nazi air power was overwhelming.

Lindbergh could envision only one rationale for joining a European conflict: to defend ‘the white races’ against ‘foreign invasion’. In his first broadcast, he argued that America should stay out of the war because the ‘white race’ was not under threat. ‘These wars in Europe are not wars in which our civilization is defending itself against some Asiatic intruder,’ he maintained. ‘There is no Genghis Khan or Zerzes marching against our Western nations. This is not a question of banding together to defend the White race against foreign invasion.’ As this war was merely a fight between ‘white races’, America could leave two equal foes to battle it out.

A month later, Lindbergh repeated the logic, saying again that America’s only obligation was to preserve ‘the white race’. ‘This is a war over the balance of power in Europe, a war brought about by the desire for strength on the part of Germany and the fear of strength on the part of England and France … Our bond with Europe is a bond of race and not of political ideology … It is the European race we must preserve … If the white race is ever seriously threatened, it may then be time for us to take our part in its protection, to fight side by side with the English, French, and Germans, but not with one against the other for our mutual destruction.’ Only ‘racial’ allegiance mattered, not political principles or democratic values, let alone sympathy with the victimised.

By 1939, Hitler’s savage persecution of minority groups, especially the Jews, was all but universally recognised. If few yet realised the extent of the atrocities taking place at the concentration camps, everyone was well aware of their existence; the Nazis had been ceremoniously opening them since 1933. Reports of mass arrests and deportations, vigilantism and torture, the murder of wholesale groups of people, as on Kristallnacht only a year earlier, were ubiquitous in the American press.

Take just a few, deliberately arbitrary, examples from 1938. That autumn, two thousand people in Cincinnati gathered to ‘protest against the Hitler government’s persecution of Jews’, at which ‘a clergyman’s unexpected demand that the United States break off all trade relations with Nazi Germany drew tumultuous cheers’.2 In a Christmas review of the key events of 1938, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle singled out ‘Jews Persecution’. ‘Hitler shocked the world with his revolting treatment of the jews [sic] in Germany.’3 The Pittsburgh Press argued: ‘The same class of reactionary financiers and industrialists who are behind Hitler’s barbaric persecution of Jews and Catholics in Germany are at work in this country.’4 In December the Daily Times in Davenport, Iowa, commented on ‘the outrage to humanity of the Hitler government’s treatment of the Jews … It has for some time been plain that it was not “purity of blood” – the Hitler Aryan myth – that dictated the oppression of Jews, but a plan to seize their wealth to bolster a faltering national economy.’5

For months it seemed that everyone in the United States, with the marked exception of Charles Lindbergh, had been talking about Hitler’s brutality towards the Jews. Lindbergh had not a word of condemnation for Hitler’s violence, insisting that there was aggression on both sides, and both sides were simply bent on preserving their own power. Indeed, he all but said in so many words that as long as some ‘white race’ was left in undisputed dominion over Europe, he didn’t much care which ‘white race’ it was.

In a widely syndicated article for Reader’s Digest in November 1939, Lindbergh spelled out his views a little more clearly, although still veiled behind careful euphemisms. As a European war would ‘reduce the strength and destroy the treasures of the White race’, the West must unite against ‘foreign races’, ‘turn from our quarrels and build our White ramparts again’. Lindbergh warned against ‘our heritage’ being ‘engulfed in a limitless foreign sea’ of ‘Mongol and Persian and Moor’, calling only for defence against ‘either a Genghis Khan or the infiltration of inferior blood’. British, German, French and American should stand together, he insisted, and the implication was clear: if that meant submitting to German aggression, so be it.

Lindbergh’s argument was markedly eugenicist, contending that white people must ‘band together to preserve that most priceless possession, our inheritance of European blood’, to ‘guard ourselves against attack by foreign armies and dilution by foreign races’. In his diaries, Lindbergh was more explicit about which people he feared were doing the diluting. ‘We must limit to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence,’ he mused, to prevent the problems created when ‘the Jewish percentage of total population becomes too high’.

The logic of the one-drop rule raised its ugly head once more, as people continued to dole out humanity to other people in percentages.

* * *

Although Lindbergh was not yet invoking ‘America first’ in the name of his isolationist arguments, plenty of other people were. ‘This writer,’ announced a citizen in Pennsylvania, ‘believes that the inventions and gifts of our good old USA, and even the hated Germany, could match all of Britain’s gifts and have plenty left over. I suppose this makes me a Fifth Columnist, for unfortunately those who are not Anglophiles and who think in terms of America First, Last, and Always, are called Nazis, etc., etc. Some day the real Fifth Columnists will be smoked out and the American people may learn the truth … America First.’6

‘Why not work for the reorganization of our high schools,’ asked a letter writer in Ohio, ‘and give our future generation a vocational college education free, instead of trying to send them over to Europe to be killed. – America First.’7

‘Let’s clean our own house of an increasing national debt, unemployment and thousands of sharecroppers, who are not much more than slaves, before we tell the rest of the world how to live,’ suggested a reader in St Louis. ‘Let’s arm to the teeth and mind our business. – America First.’8

Three weeks into the European war, Dorothy Thompson responded to Lindbergh’s first radio address by declaring that ‘Lindbergh’s inclination toward Fascism is well known to his friends’, before adding: ‘“Pity, sentiment and personal sympathy” play a small part in his life. On the other hand he has a passion for mechanics and a tendency to judge the world and society purely from a technical and mechanical standpoint. The humanities, which are at the very center and core of the democratic idea, do not interest him, and he is completely indifferent to political philosophy.’9 The implication was clear: Lindbergh was bound to find an affinity with what was already known as ‘the Nazi machine’.

Walter Lippmann also spoke out against Lindbergh’s broadcast in his column, condemning the ‘deplorable’ implication that the United States should dominate the Western hemisphere, and warning ‘against the spread of such imperialist ideas in this country and the repercussions among all our neighbors in this hemisphere’.10

Even Eleanor Roosevelt jumped into the fray in her own nationally syndicated column. ‘Mrs. Roosevelt Says He Has Nazi Tendencies,’ read a Pennsylvania headline quoting her column, in which Mrs Roosevelt spoke of the great ‘interest’ aroused nationally by both Lippmann and Thompson, who ‘sensed in Colonel Lindbergh’s speech a sympathy with Nazi ideals which I thought existed but could not bring myself to believe was really there’.11

Many Americans found Lindbergh’s arguments increasingly persuasive, however, while those sympathetic to business interests were often inclined to see in Nazism simply a hyper-efficient corporation, as Thompson had pointed out the previous year. (This was also how Nazis liked to view themselves, as Adolf Eichmann would notoriously make clear at his trial twenty years later, his complacent view of himself as a good company man prompting Hannah Arendt to identify ‘the banality of evil’.)

After Lindbergh’s first broadcast, acquaintances of Dorothy Thompson’s with ties to Wall Street spoke up in favour of American neutrality, defending the corporate nature of fascism. She lost her temper, and was heard to shout, ‘God damn it, they’ve discovered that Hitler is a good Republican!’12

Thompson went on to publish more than a dozen articles denouncing Lindbergh and the policies he represented – at least as many columns as he gave speeches and broadcasts. Just as she had become one of the most prominent voices arguing against fascism, so Lindbergh rapidly became the spokesman for American isolationism, and the battle was joined.

In January 1940, Thompson wrote a column attacking Father Coughlin’s ‘Christian Front’ as fascist. Ten days later, in response to demands that she defend the charge, she drily noted that it was Fritz Kuhn who had named the Christian Front as a ‘sympathetic’ organisation cooperating with the Bund, along with the Christian Mobilizers, the Christian Crusaders, the Social Justice society, the Silver Shirt Legion of America and the Knights of the White Camellia. Many other fascist ‘fellow travelers’, she noted, were ‘camouflaged under the names of “Christian” or “patriotic” or “American”’.13

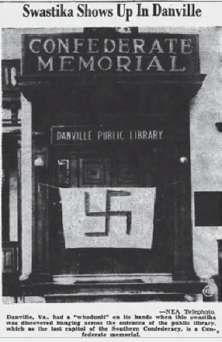

The affinity between European fascism and American white nationalism was becoming ever clearer. In July 1940, a Confederate memorial in Danville, Virginia, was draped in a swastika, a recognition that they were equivalent symbols of intimidation and terror; both were on the side of white supremacy, like calling to like.14

‘Government by agitator-led masses is not American democracy,’ Thompson wrote that summer. It didn’t matter whether a movement like ‘America first’ isolationism was widespread; that didn’t make it right. ‘The concept that there is some sacred wisdom inherent in majorities, however ignorant, is not American democracy,’ she insisted, echoing, whether consciously or not, Walter Lippmann’s criticism of what he called the American dream twenty-five years earlier.15

‘Everywhere power has been divorced from responsibility,’ she warned. ‘We have been living for a generation on unearned increment, wasting and abusing the liberties which our ancestors won for us in blood; mortgaging our children’s patrimony to pay today’s bills, which are our own. Born in liberty, we have forgotten the stern fact of liberty – namely, that it involves the highest degree of personal and group responsibility. Freedom without responsibility means anarchy.

‘We do not need to abandon democracy,’ she ended, ‘we need to go back to it – to go back to its moral and intellectual foundations and build on them again.’16

Seeking a way to distinguish those democratic foundations, ideas of ordered democracy and individual and collective responsibility for its liberties, the nation found an axiom ready to hand: the ‘American dream’ of democratic equality and justice.

For example, an extraordinary editorial from Louisville, Kentucky, in June 1940, shared around the country, began by announcing that Lindbergh’s tacit acceptance of anti-Semitism was fundamentally opposed to the American dream, before it went on to indict American racism as well. ‘Colonel Lindbergh is still worried about our meddling in Europe. He does not mention the ways in which Hitler’s Europe meddles with us,’ the item began. ‘A wicked and deadly example is the Nazi promotion in our midst of anti-Semitism.’

Just as Hitler had explained outright in Mein Kampf that people who would reject a small lie as absurd will accept an enormous lie precisely because of its outrageousness (‘They cannot believe possible so vast an impudence. Even after being enlightened they will long continue to doubt and waver, and will still believe there must be some truth behind it somewhere’), so, the editorial explained, Hitler had since taught the world ‘a lesson even more sinister’, namely, ‘that a big crime will numb and bewilder the people who would fight against smaller iniquities’.17

The sheer scale of the atrocities in Europe was desensitising Americans to it, the writer charged: ‘our minds close at the thought of half the Jews in Europe being crucified. If we could bear to face the enormous horror we would find in Nazi anti-Semitism the true symbol of totalitarian might.’18 Chaos could perversely be used to normalise what once would have seemed outrageous, as it was difficult for ordinary citizens to know where to direct their resistance.

Although in retrospect some have defended Lindbergh and other America first isolationists on the basis that they could not have predicted the range and depth of Nazi savagery, this editorial alone shows that many Americans were quite aware, at least in broad terms, of the persecutions taking place under Hitler. A local editor in Louisville knew by the summer of 1940 that ‘half the Jews in Europe’ were ‘being crucified’, and clearly assumed that all his readers knew it, too. It required neither extraordinary insight nor hindsight to make this basic fact clear.

But the Louisville editorial was not finished with America. ‘It is not an accident,’ it went on, ‘that every enemy of the American dream is an anti-Semite. Here is our Achilles heel. Whoever hates America and all she stands for has only to persuade us to this one villainy, and America is dead.’19

The American dream was of democratic justice, of equality under the law. The country made a promise to the world, and wrote it on the Statue of Liberty, the editorial observed. That promise had not been met. ‘We have failed. We have failed miserably; but we have not yet denied the dream. Even with the Negro, where our failure has been most base, we still hope and we still slowly improve. Failure can be redeemed so long as it is not excused. There is no cause for despair until man boasts of his sin, and recommends it as a virtue,’ it ended. ‘Anti-Semitism is the entering wedge for racism. And racism once accepted, America becomes an impossibility.’20

What a nation should do once it was led by men who boasted of their sins and recommended them as virtues – apart from despair – the writer unfortunately did not reveal.

* * *

Although the Louisville editorial was surely one of the most prescient and trenchant appeals to the American dream as a corrective to America first bigotries, it was not the only one. A St Louis leader argued in similar terms (redeeming the spirit of St Louis) that the American dream was specifically an image of how to create a harmonious society, one that took into account injustice and the struggles of ‘suppressed minorities’ to create a government ‘for the people’ that did not divide groups in rancour against each other. The American republic would not survive ‘through hysterical suppression of minorities’, or ‘reaction which can serve only to deepen group antagonism and class consciousness’. The nation needed instead to ‘transform into present-day reality the ideals of the freedom and equality of men which are the heart of the American dream. If government of and by the people is not to perish from the earth, it must continue to function as government for the people.’21

A widely reprinted article called ‘Intolerance in America’ shared the warning of Louis Adamic, a celebrated immigrant writer, that intolerance would ‘turn the American dream into a nightmare’. ‘There is increasing anti-Semitism,’ Adamic wrote. ‘There is also a new scorn for aliens and for naturalized immigrants. The scorn includes even their American-born children. This sort of thing does not protect democracy and Americanism.’ Instead, Americans were treating their hard-won democracy with complacency and disregard. ‘The drive against our civil liberties and cherished ideals is given an entering wedge by our own neglect and abuse of them.’22

A Wisconsin editorial predicted that totalitarian regimes would find their greatest satisfaction in a divided America. In the vitriolic upcoming US election foreign powers would find malicious gratification. ‘There is, in the present contest, the seed of just such division, and it is an evil thing. The campaign tends to blot out, if only for the moment, the essential unity of the American people.’

Americans were together, the editorial insisted, ‘as we have not been for years, in our devotion to our free institutions, standing as they do mountain-high above any president, any administration’.

Presidents come and go, but Americans must be ‘united in our determination to evolve a better social order, one that will come nearer to fulfilling the American dream of men and women free economically and politically to seek their individual destinies. Our unities are infinitely more compelling than our divisions.’23

‘Now we must have teamwork of a sort that has never been necessary before,’ an essay in Harper’s magazine exhorted its readers.

Hitler and his spokesmen say with contempt that we cannot get it and retain democracy; that the strong and competent will not work for and with the weak and incompetent. The strong and competent will decide, both for the present and for the future. If they withhold the full measure of their energy and skill now or later, our American dream will be over. With armies and navies we can doubtless stop Hitler, but not Hitlerism; for in the long run there will be only one way to give him and his henchmen the lie: by making our democracy fulfill its promises of freedom and plenty for all.24

How to protect democracy from fascism in the long run – that was the question. But the American dream – still not fixed in its meanings – was not only used to support liberal democracy, although that seems to have been by far its most common meaning at the time. Its connotations could also lead to exceptionalist arguments on behalf of isolationism, as in a letter to the Hartford Courant: ‘It would appear that the interventionist element is losing its enthusiasm for the crusade to propagate peace and democracy by means of bombs and is coming to the realization that here in America the American dream of a perfected democracy must finally be consummated.’25

Such reasoning led to rebuttals against isolationism that returned to the meaning of ‘dream’ as illusion. The Minneapolis Star retorted: ‘The “great American dream” was a pipe-dream, if by the term is meant a unique aloofness in the world.’ America could not be uniquely detached from a global world that was ‘inextricably bound together through improved means of transportation and communication’. All nations, including America, ‘must learn to live and share its life through co-operation. That we have partly failed so far is due partly to our own ineptitude and the failure of all peoples to understand the nature of twentieth century society.’26

A Pennsylvania editorial agreed that the American dream might once have been isolationist, but bluntly told the country to grow up. ‘Isolation is part of the American dream,’ it thought, because the vast majority of immigrants who had arrived since 1607 ‘came to get away from something’, again associating isolationism with ideas of exceptionalism. But the United States could no longer ‘achieve a destiny separate and unique in an interlaced world … if it ever could’.

Retreating into a ‘dream of childhood’ was as impossible for a nation as it was for a person. ‘We are grown up now, and the world, from which we might have liked to withdraw, is on our doorstep. We must play our part in that world, and play it like free men and women.’27

Dorothy Thompson also used the ‘American dream’ more than once in her fight against fascism. In the summer of 1940, she proposed ‘An American Platform’, a credo for all Americans. The column was a composite of phrases from letters she had received from readers around the world. Its language echoed the pledges during the First World War to bring the American dream to Europe in the shape of democratic liberty, promising that all Americans would fight so that ‘the American dream of freedom, of equality and of happiness may be realized by us and through us for mankind’, throughout the world, appealing to the same logic that would drive American policies during the Cold War.28

A few months later, returning to the idea that Nazi corporatism was dangerously reflected in American corporate oligarchies, Thompson argued that the American dream was viscerally opposed to such systems. ‘The concepts and values cultivated by monopolistic big business lead logically to the Nazi form of world order. The American dream rejects it with the spontaneity with which a healthy organism vomits poison.’29 Not only did Thompson hold that the American dream had nothing to do with economic aspiration; she maintained that it was fundamentally allergic to corporate capitalism.

* * *

In April 1940, Hitler let fly the blitzkrieg, as his army stormed into Denmark and Norway. Within weeks, the Nazis had overpowered Holland and Belgium, invaded France, and trapped the British expeditionary forces and their French Allies at Dunkirk, in northern France. Western Europe had all but fallen, six months into the war. Only Britain stood.

In May 1940, Walter Lippmann, by now the most influential columnist in America, responded to the British evacuation at Dunkirk in a column called, simply and devastatingly, ‘America First’.

With the Allied army and the British fleet both imperilled in northern France and Flanders, Lippmann warned, unless Hitler was stopped he would ‘master’ the Atlantic as well as Europe. ‘Let no one delude himself and others into thinking that this is just another and more exciting chapter in the long debate of the past two years as to whether the United States should help the allies a little, a lot, or not at all … The questions which we shall now have to decide will be forced upon us by the others – by the action of the Japanese and the Italians.’

It was time for American politicians to put partisan differences aside, Lippmann maintained, and unite to decide what was in the nation’s best interest. ‘If in such a moment as this we cannot count unhesitatingly upon our leaders to put the country above their party and to put their conscience above their ambitions and their prejudices, then all the defenses for which we may appropriate money will not defend America.’30

Even as Republican leaders were being urged to include an ‘America first’ isolationist plank in their platform for the 1940 national convention, an Oregon paper offered its readers a salutary little history lesson, listing five memorable events from ‘Twenty Years Ago Today – June 9, 1920. (It was Tuesday)’. The first incident from 1920 was a Republican presidential candidate from Illinois who’d said: ‘Let’s end our own woes first, and then Europe’s.’ The third was a similar reminder: ‘“America First” is keynote of Republican convention. Sen. Lodge in first talk says “defeat of Woodrow Wilson dynasty, and all it stands for, transcends all other issues along with the restoration of fundamental ideals trampled on while war raged.”’

The next noteworthy event from 1920 was ‘New reichstag near in Germany’.31 The 1920 German election had established the first Reichstag of the Weimar democracy, when the governing Weimar Coalition lost its parliamentary majority and a weak minority government was formed, paving the way for the rise of the far right, including the Nazi Party, in the 1924 elections. In other words, the apparently whimsical list of memorable events from 1920 was in fact sharply pointed, associating ‘America first’ historically with the rise of German fascism, and exposing their correlations.

Meanwhile Lindbergh kept making speeches, prompting responses such as a letter headlined ‘Heil Lindbergh’ in the Kansas Iola Register, as its author observed that the few cents the Nazi medal had cost Hitler to give Lindbergh was ‘paying big dividends’. In his most recent broadcast, Lindbergh ‘practically invited Hitler to take us over’. Americans had better start practising the Nazi salute, the correspondent recommended, and ‘learning to say Heil Lindbergh correctly or we may find ourselves in one of the concentration camps that Lindbergh and the Bund are probably preparing right now’.32

It was not until the summer of 1940 that the America First Committee, which so many people now identify as the origin of the slogan ‘America First’, was actually established.33 Originally started by students at Yale University as an anti-war movement, the coalition brought together pacifists, socialists and conscientious objectors with libertarians, nativists and fascists.

In September 1940, the unofficial student movement was taken up by far more powerful proponents in Chicago, quickly becoming America’s primary non-interventionist organisation, categorically opposed to any American involvement in the European conflict. At its peak it had more than 800,000 members from across the political spectrum, including Walt Disney, Frank Lloyd Wright, E. E. Cummings, Lillian Gish and Henry Ford, as well as young students including Gore Vidal and Gerald Ford. Isolationism made for some very strange bedfellows, uniting left-wing socialists like Norman Thomas with reactionary industrialists like Colonel Robert R. McCormick, who owned the Chicago Tribune and was one of the AFC’s founders. Sargent Shriver, the future director of the Peace Corps, and socialite Alice Roosevelt Longworth were rubbing shoulders with Father Coughlin; Democrat Senator Burton K. Wheeler joined along with Republican Senator Gerald P. Nye.

The number of industrialists on the board made many Americans ask precisely whose interests were being served; rumours that powerful Americans were financing Hitler began to circulate (and never died). In addition to Henry Ford, the committee’s president was the head of Sears, Roebuck, the treasurer was vice president of the Central Republic Bank of Chicago, and the board included former members of the American Legion, itself long called a ‘fascist’ organisation by some. The anti-war sentiments of the students who founded it soon became abrogated by other motives and policies; Lindbergh, however, did not immediately join.

The AFC saw themselves as anti-imperialists, many equating the British Empire with Nazi Germany and the Japanese Empire in arguments that were all but indistinguishable from those made by the America Firsters of the First World War. That summer, Lindbergh had invoked the old ‘foreign entanglements’ shibboleth. ‘We have by no means escaped the foreign entanglements and favoritisms that Washington warned us against when he passed the guidance of our nation’s destiny to the hands of future generations … Our accusations of aggression and barbarism on the part of Germany, simply bring back echoes of hypocrisy and Versailles.’34

In December 1940, Dorothy Thompson took direct aim at the America First Committee. ‘We are beginning to see a concerted move, backed by a great deal of money, supported by one section of the press and one section of congress, and assisted by a high-pressure advertising campaign,’ she charged, with but one purpose: to ‘collaborate for a Hitler peace’. They would claim that blocking supplies and aid to Britain was simply ‘protecting America first’, she warned, thus bringing about a Hitler victory with high-minded calls for armistice. ‘The movement, already well under way, is “100 per cent American,” and it follows to a “t” the line being promoted by the Nazi propaganda.’35

The America first movement was backed ‘enthusiastically’, she observed, by the German-American Bund. The ‘Nazification of the United States’, Thompson wrote, was also sought by ‘personally ambitious’ extremists, including Lawrence Dennis, author of The Coming American Fascism, whose object was ‘despotic power based on mass seduction’. ‘First to be removed are the “articulate 10 per cent,” and they are silenced by calumny, terrorization and economic pressure. The new elite of brain-trusters steps in to rationalize the new order as socialism for the masses, and security for the classes. Thus, if it ends, will end Jefferson’s and Lincoln’s dream.’36

Suddenly America was facing a world, Thompson noted, ‘where tyranny is young again, and Democracy old’.37

In February 1941, she described what she saw as the blueprint of ‘native fascism’. ‘American Fascism, while preaching isolation from Europe, is designing a program of American imperialism which is a copy of Hitler’s continental imperialism. The outlines of it are most clearly discernible in the speeches of Colonel Charles A. Lindbergh. It consists of giving Europe to Hitler and Asia to Japan and Russia, in return for a new Monroe Doctrine … We are to be the Master Folk of the Western Hemisphere.’38

This idea made her remember, she said, something that Huey Long had once told her. ‘American Fascism would never emerge as a Fascist but as a 100 per cent American movement; it would not duplicate the German method of coming to power but would only have to get the right President and Cabinet.’ Moreover, Long had added, ‘it would be quite unnecessary to suppress the press. A couple of powerful newspaper chains and two or three papers with practical monopolies of certain fields would go out to smear, calumniate and blackmail opponents into silence, and ruthlessly to eliminate competitors.’ When American fascism came to power, ‘it would be war on neighbors, war on liberals, war on racial minorities, militarism …’39

All it would take was one powerful news organisation to support it.

That same month Thompson also responded to Henry Luce’s influential column ‘The American Century’, in which he argued that the twentieth century would be either the American century or the Nazi century. Her rebuttal ended by castigating ‘the floundering timidity that has cursed our policy ever since the last war. If we had been doing our part in the world this war would not have happened. Now we must do it or take a back seat in history. This will either be an American century or it will be the beginning of the decline and fall of the American dream.’40

A few weeks earlier, President Roosevelt had delivered a State of the Union address in which he called for ‘a world founded upon four essential freedoms’ that distilled the principles of democracy: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear. ‘That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.’

Within a few months, Roosevelt’s four freedoms were converging with the American dream, as in a series of discussions at the University of Iowa that summer, which announced that their ‘text’ was the ‘Four Freedoms’, and began from the premise that ‘democracy is now meeting its greatest challenge since 1776’. ‘The University of Iowa’s plan is to counter totalitarian attacks on the democratic philosophy’ by analysing ‘the so-called “American Dream” and what is meant by democracy in American terms’.41 An organisation called the Council for Democracy took out advertisements that featured the US Capitol as the nation’s ‘symbol of democracy, power behind the powerhouse of freedom. Our American conscience, our American dream, our American devotion to the Four Freedoms.’42

Editorials responded to criticisms that it was ‘impractical to spread the four freedoms about the world’ by urging America to recognise that an ideal world was ‘a world which needs our work’, and ‘the response to the need has quickened the old American dream of work … We shall cherish the world’s needs; it is the only way of filling our own.’43

The America First Committee declared that Roosevelt was seeking to impose the four freedoms by tyrannical force. Republican Senator Henrik Shipstead gave a radio address sponsored by the AFC, in which he demanded: ‘Does it seem sensible to depose dictators and impose upon foreign peoples, dictators according to our own liking, who will force the four freedoms upon their people who have never heard of the four freedoms?’44

* * *

Charles Lindbergh officially joined the America First Committee in April 1941, travelling around the country speaking before audiences of thousands, often in front of a symbolic picture of George Washington, as America First rapidly gained in strength and popularity.

Thompson responded instantly, and bluntly, to Lindbergh’s joining the AFC in a column called ‘Lindbergh and the Nazi Program’. Not pulling any punches, she announced: ‘I think that Colonel Lindbergh is pro-Nazi. I think that he envisages America as part of Hitler’s “new order” and himself as playing a leading role in the American end of that new order … In the Chicago speech, which had the full support of the German-American alliance to the traitorous bund, he advocated a “treaty” with the dominant power of Europe, as the only way of securing peace.’45

That spring Liberty magazine reported that a nightclub song had recently gained popularity in Nazi Germany.

Maybe it scans better in German. Or maybe it was concocted. But regardless, the story circulated around the country, suggesting widespread unease at Lindbergh’s apparent Nazi sympathies.

A week later, Thompson attacked Lindbergh’s ‘grotesque crusade’ to persuade America to make a non-aggression pact with Germany, accusing him of collaborating by likening him to the complicitous leader of Nazi-occupied Norway. ‘This is not Hitlerism, it is Quislingism,’ she alleged, ‘the last and most grotesque form of Fascism.’47

At such times, Thompson added, ‘“America first” takes on a really ominous significance – ominous, but somehow ridiculous’.48 Many Americans agreed. ‘Pathetic to see Lindy voicing views of Nazis,’ read one letter to the Pittsburgh Press, ‘delivering lurid speeches nicely calculated to further terrify the already craven-hearted America Firsters.’49

In practice, Thompson repeatedly wrote, at best America First meant appeasement; at worst, it was simply surrendering to fascism. ‘Tell me what American pacifists, America First members, American communists, socialists, labor leaders, and anti-imperialists are saying today, and I can write you Hitler’s speech for tomorrow. He knows that democracies can best be destroyed by democracy’s own slogans. Their destruction is his sole aim and the sole purpose of his propaganda.’50

Although Thompson was certainly one of Lindbergh’s most public critics, she was by no means the only prominent one. In a 1941 speech before the Jewish National Workers Alliance of America, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes called Lindbergh ‘the No. 1 U.S. Nazi Fellow Traveler’, saying baldly, ‘he wants Germany to win … It would seem that he prefers fascism to democracy; that he is indifferent to liberty … and condones, if he does not actually applaud, the brutalities of which the Nazi ideology has already been guilty.’ Refusing to call them the America First Committee, Ickes referred to them instead as ‘the America Next committee’, adding that they were all ‘Nazi fellow travelers’ and Hitler’s ‘dupes’.51

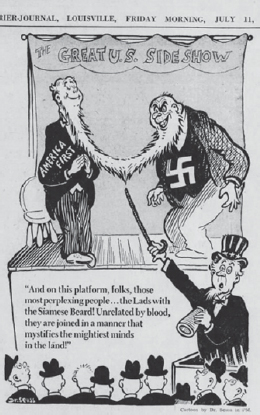

That summer a series of anti-isolationist cartoons were reprinted around the country, including several denouncing America First as Nazi sympathisers, drawn by Theodore Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr Seuss.

Although the Chicago Tribune supported the movement in its editorials, other papers condemned the AFC as ‘the Fascist Front in America’, listing some of the individuals associated with the movement, among them the various leaders of the Bund, the KKK, the Christian Front and Christian Mobilizer and the American Destiny Party, as well as Lawrence Dennis (Fascist ‘theoretician’).52 ‘All of these organizations are recognized to be pro-Nazi appeasement agencies which have united upon Lindbergh’ as leader, wrote an Iowa paper; under the pretext of peace, they were joined in ‘doing the work of Hitler in America’.53

They continued to be supported by Americans around the country, however, sending letters under the headings or signatures of ‘America First’. ‘America must come first! We positively cannot afford to fight Hitler on his own terms … Is the question before us to save England and imperialism, or is it to save ourselves?’54

‘Wake up, Americans, and fight for your rights!’ pronounced one citizen signed ‘An American’. ‘Keep our money at home … Look up the history of England and you’ll find that she got her land by the same method Hitler is now getting his. I am for America first, and only for America.’55 Another ‘America First’ correspondent warned that entering the war on the side of Great Britain would mean the United States would finish the war having become a British colony again.56

In May 1941, it had suddenly been announced that Sinclair Lewis had joined the America First Committee; by that point he and Dorothy Thompson had quietly separated.57 According to Lewis’s biographer, he was ‘at that time vigorously opposed to American intervention in the European war and was quite cool toward Franklin D. Roosevelt, his sympathies with the America First people’. It may also have been more personally motivated; as their marriage was unravelling, Lewis was said to have vowed: ‘If Dorothy comes out for war, I’ll take Madison Square Garden and come out against war.’58

That spring Walter Lippmann, too, had spoken up once more against America first, with considerably less amusement than he had directed at Hearst seven years earlier. Lippmann forcefully argued that isolationism made no sense as a policy of appeasement, because isolation would leave America alone, either to fight or to surrender: ‘surely it cannot be argued that standing alone in the last ditch against a world of enemies is a desirable situation, that it is anything but an appallingly dangerous one which a sane people will, while it still can, do all in its power to avert’.59

Unsurprisingly, the America First Committee also claimed the American dream, again uniting isolationism with exceptionalism. ‘Americans! Wake Up!’ the AFC exhorted in an advertisement, urging everyone to write to the president demanding America stay out of the war. ‘In 1776 three million Americans dared to sign a Declaration of Independence, unsupported by any foreign navy, unafraid of any foreign economy. And the “American Dream” was born.’ Americans must insist ‘you will not out of fear countenance KILLING and SLAUGHTERING in “many and varied terrains” in the so-called “defense of this country”’.60

The argument was not universally accepted. ‘What has happened to you, America First?’ demanded an opposing advertisement taken out by Fight For Freedom, Inc., which called for ‘immediate unrelenting action to crush Hitlerism’. ‘You claim you are trying to think of America first, but can’t you think a little more clearly?’61

As it became more evident that pro-fascist sympathies were aligning themselves with the supposedly pacifist AFC, Lindbergh was widely criticised for having ‘rebuffed repeated efforts’ to publicly reject the ‘fascist elements’ attached to the organisation.62 A spokesman for the Veterans of Foreign Wars denounced the ‘sinister support from Bundist, Fascist, and Silvershirt organizations’, calling ‘upon the America First Committee to purge itself of these treacherous elements’.63 But they did not.

* * *

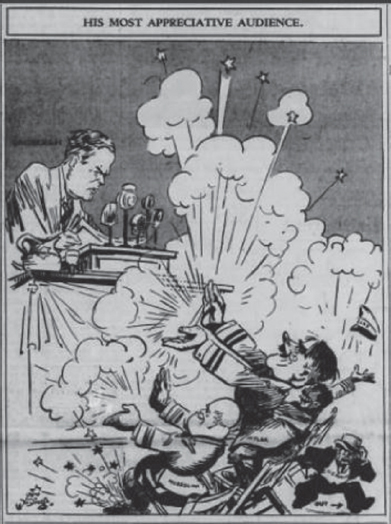

On 11 September 1941, Lindbergh travelled to Des Moines, Iowa. Although his appearance made the front page of the Des Moines Register that morning, he was not necessarily welcomed with open arms. ‘His Most Appreciative Audience,’ read the caption of a front-page cartoon depicting Lindbergh speaking to a rapturously applauding Hitler, Mussolini and Hirohito, while a small man in the corner labelled ‘U.S. Public’ grabs his hat and heads ‘out’, with an arrow showing the way.

In his Des Moines speech, Lindbergh claimed that it was in the best interests not only of the British but of the Jews to drag the US into the European conflict. Their interests were not America’s interests, he insisted, while Jews’ (supposed) control of the nation’s media, films, businesses and government posed a threat to the country.

It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany. The persecution they suffered in Germany would be sufficient to make bitter enemies of any race. No person with a sense of the dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany. But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy both for us and for them. Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups in this country should be opposing it in every possible way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences. Tolerance is a virtue that depends upon peace and strength. History shows that it cannot survive war and devastations. A few far-sighted Jewish people realize this and stand opposed to intervention. But the majority still do not. Their greatest dangers to this country lie in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government.

His language strongly recalled the argument made by Fritz Kuhn before the German-American Bund in 1938, when he complained that ‘the American press and radio were controlled by Jews “who are trying to smash this country even as they tried to ruin Germany”’, the old conspiracy theories of a Jewish cabal controlling global media and finance circulated in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion – which was also, of course, the pretext that had been offered by the Nazis.64

Father Coughlin had made similar claims about Jews’ control of finance and media, but Lindbergh went too far. The dog whistle was too loud; codes don’t work if what is supposed to be covert becomes overt. The Des Moines speech prompted a national outcry.

Iowa papers declared that Lindbergh’s ‘resort to racial and political prejudice’ had brought forth ‘unanimous protest from the press, the church and political leaders’.65 The Kansas City Journal announced: ‘Lindbergh’s interest in Hitlerism is now thinly concealed.’66 The New York Herald Tribune denounced the ‘dark forces of prejudice and intolerance’, especially the anti-Semitism, that the speech marshalled.67 The Chicago Herald Examiner declared: ‘the assertion that the Jews are pressing this country into war is unwise, unpatriotic and un-American’,68 while the Omaha World Herald deplored the speech’s ‘slimy weapons of hate and prejudice’, which were ‘as un-American as the swastika, as venomous as a rattlesnake’. ‘The voice is the voice of Lindbergh,’ wrote the San Francisco Chronicle, ‘but the words are the words of Hitler.’69

In a widely reprinted editorial, Liberty magazine called Lindbergh ‘the most dangerous man in America’. Revealing ‘the sincerity of the witch burner’, he had given anti-Semitism a platform, which until then ‘was a back-alley business’ in the US, led by ‘shoddy little crooks and fanatics sending scurrilous circulars through the mails. There were many of them, it is true, but none was important.’ Now Lindbergh had legitimised their views, issuing ‘a summons to the pogrom’. Lindbergh was not only ‘America’s number one Nazi’; he was ‘the forerunner of Hitler, ambassador of the Antichrist, Fuehrer of the forces of hell’.70

In response to the outrage, the AFC fanned the flames further by issuing a clumsy statement saying they deplored the ‘injection’ of ‘race issues’ into the debate over the war – but then claiming that the interventionists had done the injecting, not them, as if protesting against Lindbergh’s anti-Semitism was what made anti-Semitism an issue.

The claim that there was intolerance on many sides provoked sarcastic outrage: it was like saying the war ‘was started by Poland’s treacherous assault on Germany’.71

In an editorial headlined ‘The Un-American Way’, the New York Times called the Des Moines speech ‘completely un-American’, demolishing the AFC’s attempt to blame interventionists for ‘the injection of the race issue’ into the debate. Pointing out the racism inherent in this supposed defence by demanding ‘whether a religious group whose members come from almost every civilized country and speak almost every Western language can be a called a “race”’, the Times then turned to Lindbergh’s words and their ‘clear echo’ of ‘Nazi propaganda in Germany’.72

Noting that the America First Committee’s refusal to ‘disown one syllable of these statements’ meant that it ‘associates itself with them’, the editorial went on to argue that ‘the most sinister aspect’ of the speech was not its ‘appeal to anti-Semitism, however obvious the intent to make that shameful appeal may be’. America would never condone anti-Semitism, it insisted. ‘What is being attacked is the tolerance and brotherhood without which our liberties will not survive. What is being exposed to derision and contempt is Americanism itself.’73

As people called for Lindbergh’s name to be removed from streets, bridges and his home town’s water tower, even Hearst ran an editorial denouncing the speech, giving wide coverage throughout his papers to criticism of Lindbergh’s words. ‘Mr. Lindbergh has made an un-American speech,’ the editorial concurred. ‘The assertion that the Jews are pressing this country into war is unwise, unpatriotic, and un-American’, while his claim that they controlled the media ‘sounds exactly like things that Hitler said’, it added.74 Roosevelt’s press secretary Stephen Early also publicly noted ‘a striking similarity’ between Lindbergh’s speech and recent ‘outpourings of Berlin’.75

Dorothy Thompson accused Lindbergh of trying to ‘blackmail’ Jewish Americans; others saw in his language a clear threat. William Allen White maintained it was ‘moral treason’, adding: ‘Shame on you, Charles Lindbergh, for injecting the Nazi race issue into American politics.76 The Des Moines Register called it ‘a “smear” speech’, ‘so intemperate, so unfair, so dangerous in its implications’ that it ‘disqualifies [Lindbergh] for any pretensions of leadership of this republic in policy-making’.77 The AFC stopped inviting Lindbergh to speak, and sought belatedly to distance themselves from him.

In November 1941, Thompson gave an outspoken interview to Look magazine, headlined ‘What Lindbergh Really Wants’, widely quoted from in the press. She was ‘absolutely certain in [her] mind that Lindbergh is pro-Nazi’, she stated; he intended to ‘be President of the United States, with a new party along Nazi lines behind him’.

‘Lindbergh thinks that America will enter the war, and he thinks that America will lose it. He will then emerge as the one who said “I told you so.”’ Pressed on how she knew this about him, she explained: ‘I recognize the manner, the attitude, the behavior of the crowds, the nature of Lindbergh’s following, the equivocal speech, the sentiments that are played to, the line of reasoning that is no reasoning. I knew from his very first speech, a speech that on the face of it was harmless, that in a few months he would come out openly against the Jews.’

He was the kind of person she had long predicted would seek ‘the Nazification of America’, although she hadn’t known that person’s identity. Whoever it was would be, as Lindbergh was, followed by ‘rabidly disgruntled Republicans – especially industrialists – neglected politicians, frustrated socialists, Ku Klux Klanners – whether they call themselves Christian Mobilizers or what – and a number of neurotic women. He would preach the purification of American life and he would have a slight martyr complex. Most of his followers would be completely ignorant of his real program.’78

Lindbergh’s followers revealed the true nature of his politics, she held. ‘He has attracted to himself every outright Fascist sympathizer and agitator in the country.’ The mere fact that the Klan supported him ought to give everyone pause, she maintained, noting that he was also supported by all the anti-Semitic groups of ‘Jew-baiters’ who styled themselves the ‘Christian’ this or that. Those were reason enough to discredit him.

‘The whole crowd of them consider Lindbergh their leader,’ Thompson said. ‘They are his shock troops, and he has never made an unequivocal break with their ideas …The whole setup is Hitlerian. These boys are violent. They use free speech to stir up violence.’79

It was a matter of understanding how to read fascism, she insisted. ‘I know the handwriting. This man has a notion to be our Fuehrer.’

Two weeks later, on 7 December 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, and the United States entered the Second World War. Four days after that, the America First Committee officially disbanded and pledged its support to the American war effort.

Thompson responded to Pearl Harbor with a column not about Lindbergh or fascism but about the debasement of the American dream. The attack had happened, she believed, because America had contented itself for decades with a degraded ideal, a dream of just getting by. ‘For a whole generation the American ideal has been to get as much as it could for as little effort,’ she charged. ‘For a whole generation the American motto has been, “I guess it’s good enough.”

‘We have admired success, and success has been measured in money … The question has not been “How well is it done?” but “How much does it pay?” And mediocrity – in high places and low – has been the American dream … to “get by with things,” to make pleasure and leisure the aim of life, to indulge in fatuous optimism, to be certain that in some way “everything will turn out all right,” and to run screaming after a scapegoat if it didn’t.’

The American dream had become a sense of complacent entitlement, one that quickly turned resentful when easy promises weren’t fulfilled.

Thompson urged her readers to remember ‘the eternal American – the American who did not “buy” independence but wrenched it from fate with blood. The American who did not “sell” an idea but thought it and created it … That American is still here, under all the lax habits, fretful under them, struggling through bonds of luxury toward greater cleanness and hardness. Had you forgotten, Americans, that luxury can be the worst bondage of all?’

It was no good just blaming the fascists, she concluded. ‘I accuse us. I accuse the twentieth century American. I accuse me.’80