PRELUDE

MONDAY, DECEMBER 1, 1958, had broken clear and cold in Chicago.

The temperature outside was a chilly nineteen degrees when John Raymond awoke in his family’s apartment on Hamlin Avenue. Monday was the first day back to school since classes had ended the previous Wednesday for Thanksgiving. It was also the first day of Advent, when Christians, and Catholics in particular, prepare for the Christmas holy season.

John was eleven years old, a fifth-grader at Our Lady of the Angels School a block away, and one of seven children in his family. He had recently marked his church confirmation, a rite of passage for preadolescent Catholics, and to cap the occasion his parents had scraped together enough money to buy him a new bicycle, a red-and-white Sonic King purchased from the local Sears, Roebuck store on Homan Avenue. The bike, with its wide handlebars, shiny chrome rims, and thick whitewall tires, was the envy of every boy who passed it on display. For John it was a dream come true. He had been anxious to break it in, but freezing weekend temperatures and a light dusting of snow had curtailed his plans for an inaugural spin through his neighborhood. Instead of whisking down its side streets, showing off to his friends, he had spent much of his Sunday staring out the window, dreaming of spring.

On Sunday the city had registered its coldest day of the season. The mercury at Midway Airport, the world’s busiest, had dipped to two degrees above zero. But Monday promised to be warmer, with temperatures forecast to reach into the thirties. John peeked through the curtains. The skies were clear, the streets dry. Maybe after school he could take the bike out for a ride.

With six brothers and sisters, John had never had a bicycle he could call his own. His dad, Jim, a tall, slender forty-three-year-old, was employed as head janitor at Our Lady of the Angels parish, a position that paid little but demanded much. Although the elder Raymond often felt he was lucky enough just to put food on the table for his large brood—let alone buy new bikes for each of the kids—he also knew he had a steady, honest job that allowed him the use of his handiwork skills.

Jim Raymond began working at Our Lady of the Angels in 1945. He was responsible for the upkeep of all parish properties, including the church, school, convent, rectory, and community center. In time he had come to consider the buildings as extensions of himself. His budget might be limited, but he tended the properties with care, maintaining a regular schedule of sweeping and mopping floors, wiping windows, and burning trash. It was a heavy workload, and with the exception of one part-time assistant and an elderly retiree who would occasionally give him a hand, the janitor received little help with his chores. His workday usually began around 5:30 in the morning, and sometimes, aside from dinner with his family, would not end until 9:30 at night. Despite these demands, in the thirteen years he had worked at the parish Raymond had come to develop a deep respect for his boss, Monsignor Cussen. The two men shared a close friendship.

During the winter months Raymond fed the school’s coal-burning furnace several times each day, often returning in the early morning hours to stoke it again so that the building would be warm when the children arrived for classes. Many times, when he required help with bigger jobs, he would troop up to the eighth-grade classrooms and enlist a few of the older boys. Raymond’s fourteen-year-old, Bob, often was one of the lucky “volunteers” pulled from class to help in such tasks. It would happen that Monday afternoon when Bob and a dozen other boys would be dismissed early from Room 211 to help load old clothes onto a truck as part of the parish’s annual clothing drive for needy families.

The parish and its people represented obvious focal points for the Raymond family. The children’s mother, Ann, herself a graduate of Our Lady of the Angels, had grown up in the neighborhood. She had met her husband in the late 1930s after he had come to Chicago from his home in Holland, Michigan, in search of work. After their marriage in Our Lady of the Angels Church, the couple set up house in the same yellow-brick two-flat they still called home.

Now, after seven children, the apartment at times seemed to be bursting at its seams. In the mornings the hallway leading to the bathroom often was crowded as the kids took turns washing their faces and brushing their teeth.

The morning of December 1 was no different.

THE 1953 BROWN Chevy coupe sped along the ribbon of concrete linking Chicago’s South Side with the Loop. Richard Scheidt was making good time in the rush-hour traffic on South Shore Drive. To the left, the barren trees of Jackson Park whizzed by, exposing the sprawling, grey Museum of Science and Industry, built for the 1893 Columbian Exposition. Off to the right, Lake Michigan glistened, and the morning sun, an orange ball, hung just above the horizon.

Thirty and balding, Scheidt had left his wife and four children in their six-room bungalow on West 97th Street shortly after seven o’clock. Like many Americans of the era, he had become accustomed to the cold war, and during his half-hour ride to the firehouse he paid little attention to the Nike missile installation near 53rd Street, one of sixteen that encircled the Chicago area. Its radar domes, scanning the skies for Russian bombers, frequently caught the eye of passing motorists.

Chicago’s downtown skyscrapers loomed on the horizon. Burgeoning traffic forced Scheidt to slow his car near R. R. Donnelley’s Lakeside Press, where, inside the huge plant, presses were already at work churning out the day’s quota of telephone books, catalogs, and magazines. To the east, at the lakefront, the city’s new exposition center, McCormick Place, was under construction.

The brown coupe again picked up speed as the traffic bottleneck cleared. The Grant Park bandshell and the expanse of brown grass surrounding it looked especially lonesome that cold, crisp morning. But beyond the bandshell, to the north, the Prudential Building was a commanding sight. Chicago’s tallest building and the city’s first skyscraper since the Great Depression soon would be jammed with tourists and proud locals eager to see the city from its observation deck, 614 feet above Randolph Street.

Scheidt was only minutes from the old firehouse at 219 North Dearborn Street, the quarters of Engine Company 13 and Rescue Squad 1. He looked forward to a good cup of coffee with his comrades on the squad.

The city had thirteen rescue squads, several of them busier than Squad 1, but it enjoyed the most prestige because its district encompassed the Loop and the Near North Side. While a squad could be dispatched anywhere in the city in an emergency, Scheidt and his fellow squadmen were chiefly responsible for what fire underwriters called the “high value” district: the La Salle Street financial hub, the fashionable Michigan Avenue shopping area, the high-rises and exclusive mansions along Lake Shore Drive, and City Hall itself.

There was money in the Loop, and the Fire Department traditionally stationed its newest and most elaborate equipment there—equipment that could be seen by the many Chicagoans and tourists who frequented the area. The Dearborn Street firehouse was the closest to Room 105, City Hall, the office of discipline-conscious Fire Commissioner Robert J. Quinn.

Following his two older brothers, Richard Scheidt had joined the Fire Department in 1951 and had chosen squad work. He liked the camaraderie and extra hustle of the men on the “dizzie wagons,” a nickname that came from their seemingly constant activity. At fires, squadmen opened roofs, pulled ceilings, conducted search and rescue, and helped engine companies with hose lines. But a special-duty call could mean anything—a heart attack victim, a serious auto accident, a jumper in the nearby Chicago River, a rescue from a building collapse. Squadmen swore that when they arrived at a fire, other firemen on engine and truck companies would begin to work harder. The “regulars” disagreed, calling the whole thing conceit. Any superiority—real or imagined—was not reflected in pay. Scheidt earned no more than any other first-class Chicago firefighter: $5,400 a year.

The silvery Christmas decorations on the light poles along State Street hardly caught Scheldt’s eye as he drove west on Randolph Street. The streets were still deserted and the thousands of bulbs on the large theatre marquees were dark. At 9 a.m., when those marquees came alive, beckoning early theatregoers to The Geisha Boy, I Want to Live, and Anna Lucasta, Scheidt would already have been to his first fire of the day.

Leaving the marquees behind, Scheidt parked his car and entered the three-story red-brick firehouse built in 1872, a year after the Great Chicago Fire. At 8 a.m. the bells inside the station began their incessant clanging, a signal that the shifts were changing. Putting down his cup of coffee, Scheidt walked to the front of the house and joined the other five members of the squad for roll call.

The new twenty-four-hour shift was beginning.

FIVE MILES AWAY, on Chicago’s West Side, the same eight o’clock signal from the main fire alarm office was ringing bells inside the quarters of Engine Company 85, where Lieutenant Stanley Wojnicki and his four-man crew also were coming on duty. The old brick engine house, built in the days of horse-drawn fire apparatus, stood on the corner of Huron Street and Lawndale Avenue, three blocks south and two blocks east of Our Lady of the Angels School. Inside, behind narrow red doors that opened at the middle, the company’s 1951 Mack pumper, equipped with fifteen hundred feet of hose and one twenty-four-foot extension ladder, stood at the ready, awaiting its next alarm.

In 1958 Chicago was protected by a firefighting force of 126 engine companies, 59 hook-and-ladder companies, and 13 rescue squads, all divided into 30 battalions and 6 divisions. These units, each manned by five to six firefighters, were the city’s frontline defense against fire, and each was responsible for covering its own “still district.” The area covered by Engine Company 85, part of the 18th Battalion, was typical of a crowded, working-class neighborhood—modest bungalows, apartment buildings, light industry, and small businesses. The company didn’t see many fires, and despite the bustling nature of its district, compared to other fire companies in the city it was on the low end of the activity scale—a “slow outfit” in a well-kept area.

Supplementing the engine and truck companies of the Chicago Fire Department were nineteen Cadillac ambulances, each manned by two firefighters with about eight hours of basic Red Cross first-aid training, and a host of other specialized vehicles and apparatus, including smoke ejectors, “water towers” (elevating platforms with hoses), high-pressure rigs, and light wagons. Among the new additions to the department’s fleet in 1958 was the “snorkel,” an elevating platform fitted with a basket and hose nozzle perched atop two hydraulic booms. The snorkel was the brainchild of Fire Commissioner Quinn, who had gotten the idea for the new apparatus after watching city workers in gooseneck cherry pickers trim trees in Lincoln Park.

Sitting on watch at his desk near the front of the firehouse, just beneath the loudspeaker linking Engine 85 with the downtown alarm office, Lieutenant Wojnicki began his paperwork, signing his name in the company logbook to indicate that his platoon had taken over. Across the street, the sidewalks were crowded with children streaming into Ryerson public elementary school. Roll call had ended and the firemen were busy checking their equipment, making sure the pumper’s water tank was full, that everything was ready to go.

A short, stocky, muscular figure with jet-black hair and a pleasant demeanor, Wojnicki was dressed in his regulation white shirt and navy blue trousers. Pinned to each lapel of his shirt was a silver bugle denoting his lieutenant’s rank. As he completed his morning routine, a small transistor radio on his desk kept him company:

“President Eisenhower has once again warned the Soviet Union the United States will not withdraw from Berlin….

“In France, President Charles de Gaulle’s right-wing party has scored a parliamentary victory over the Communists….

“Meanwhile, in this country, the president says he looks forward to 1959 bringing recovery for the American economy, now in its fifth month of recession….”

Chicago sports news was less encouraging:

“Only 13,000 football fans showed up at Comiskey Park Sunday to watch the Cardinals lose to the Los Angeles Rams, 20 to 14. The Bears, in Pittsburgh, were defeated by the Steelers …”

The weather report was more cheerful: “Partly cloudy today, not so cold.”

That’s good, Wojnicki thought. Since joining the Fire Department in 1943, he had been to his share of winter blazes, and he knew that cold weather with its greater use of heating facilities brought more fires. But he felt at ease, for he was in charge of a good group of firefighters, men skilled in their jobs. And on this Monday the company was at full strength: an engineer to drive and work the pump, three firefighters, and himself.

Wojnicki was a good firefighter and a levelheaded officer who knew his district intimately. An orphan, he was forty-three years old and had grown up in this same neighborhood, raised by an older sister. His childhood home was about a mile from the firehouse, and he made his first Holy Communion and confirmation in the old Our Lady of the Angels Church, the building that by 1958 had been converted into the north wing of the parish school.

After his marriage Wojnicki stayed in the neighborhood, buying a two-flat building on North Ridgeway Avenue. He was disappointed when his dream of becoming a police officer was cut short—literally—by the department’s height requirement. Wojnicki stood five feet, eight inches tall; incoming police recruits had to be a minimum five feet, nine inches. Instead he took the fireman’s test, coming out number twenty-one on the eligible list. When the time came for him to report for duty, he had unaccountably decided to turn down the appointment, but he went ahead and accepted the job, following the advice of his brother-in-law, a police officer, who had threatened to “belt him one” if he didn’t take it.

After finishing drill school, Wojnicki’s first assignment in the Fire Department had been with Engine Company 85. He later transferred to nearby Engine Company 68, on North Kostner Avenue, but returned to Engine 85 in 1953, after his promotion to lieutenant. The promotion brought with it a bigger paycheck, and in February 1958 Wojnicki, with his wife and three sons, packed up and moved to a larger home on the city’s North Side. Until then he had been an active church parishioner, and the oldest of his three children had been a student at Our Lady of the Angels School.

Although he no longer lived there, Wojnicki still enjoyed the old neighborhood. He fit comfortably into the community of friendly, family-oriented people. If matched against the achievements of the movers and shakers of society, his life would seem rather routine, measured by twenty-four-hour shifts at the firehouse followed by forty-eight hours off duty. But if there was a sense of ordinary commonplace to Stanley Wojnicki’s life, it would come to an abrupt end later that afternoon.

FOR THE NUNS who taught at Our Lady of the Angels School, the Monday also had begun early. The Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary devoted their lives to prayer and teaching, and began their morning by offering daily devotions inside the wood-paneled chapel of their convent across the street from the parish school.

The BVM order had been founded in 1833 by Sister Mary Frances Clarke, and it began serving the Chicago archdiocese in 1867. The order, dedicated to works of education, was known for its teachers, whose appearance was distinguished from other religious communities by the large square hoods they wore atop their heads. They had another distinction as well: a concern about fire. In 1870 their motherhouse in Dubuque, Iowa, had burned to the ground, and since then—for eighty-eight years—all members of the order offered daily prayers asking that they and their pupils be spared from fire. Monday, December 1, was no different.

After finishing breakfast in the convent dining hall, the sisters walked across Iowa Street to their classrooms in the parish school. They were dressed in their traditional ankle-length black habits offset by stiff hoods and white fluted borders and collars. The women painted a picture of delicate gentleness, and their fair skin glowed in the sunlight. In little more than a half-hour, these graceful visions in black and white would act and appear quite different—as queens before their small, often awestruck charges.

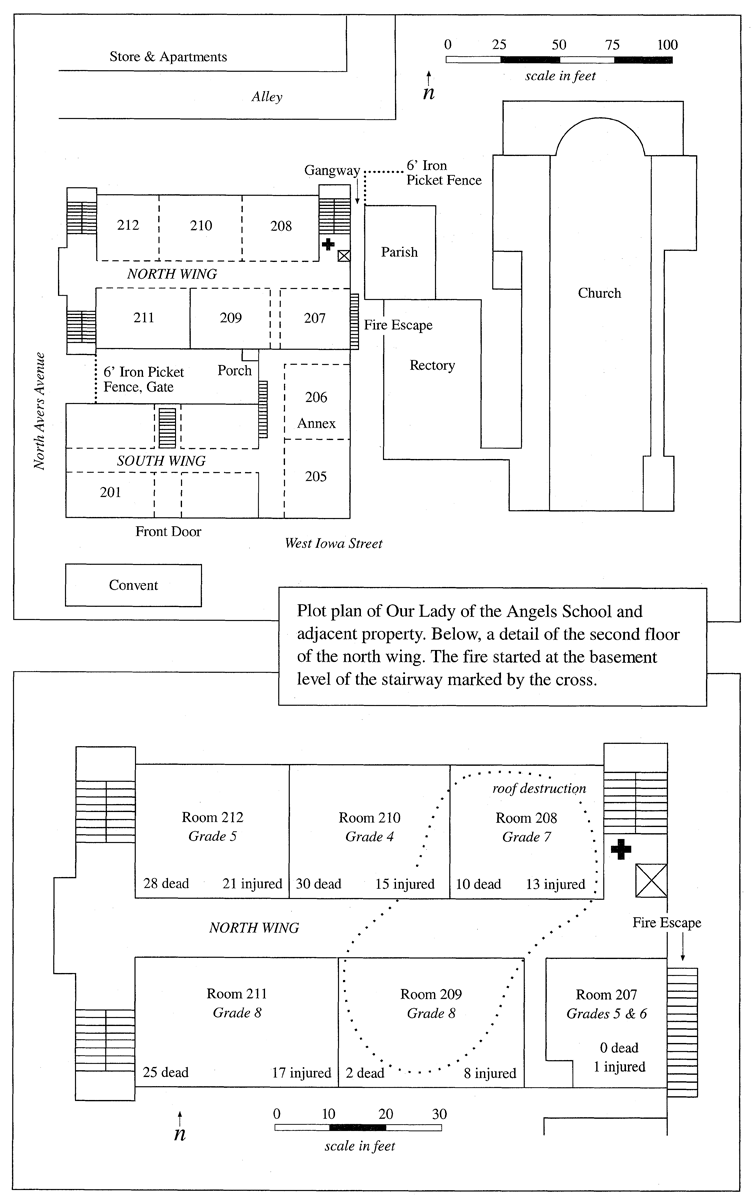

Sisters Mary Davidis Devine and Mary Helaine O’Neill, two of the older, more experienced nuns, climbed the worn wooden stairs to their eighth-grade classrooms on the second floor of the school’s north wing. The pair had enjoyed their holiday weekend but were happy to be back to work.

Sister Davidis took up her post at the front of Room 209, a classroom with a high ceiling, varnished hardwood floor, and plenty of wood trim. After wiping clean her spectacles and organizing her desk, she began jotting notes on the chalkboard. The sixty-two pupils assigned to her would be arriving soon, and there was much work to be done.

A teacher for thirty-four of her fifty-two years, Sister Davidis loved her profession, and her students knew it. There was a sense of freedom in her classroom despite the omnipresent atmosphere of Catholic school discipline. Although a tug on a pupil’s ear might occasionally be necessary if that freedom went too far, the years had taught her that equal doses of order and free reign made learning less of a chore.

The contrast in Room 211 next door was sharp. At age fifty-six, Sister Mary “Hurricane” Helaine towered over her sixty-four pupils; the threat of discipline that she represented usually was sufficient to maintain order in her classroom. If not, a gentle reminder, like a jabbing finger, was all that was necessary. From the students’ perspective, Sister Helaine was one of the most feared nuns in Our Lady of the Angels, and youngsters in the lower grades knew they had a fifty-fifty chance of meeting this formidable “obstacle” on the way to graduation.

Across the hall, in Room 208, near the back stairway, Sister Mary St. Canice Lyng was busy writing notes in her appointment book. A regal-looking nun with pince-nez glasses, she planned to spend part of the day teaching European history to her forty-seven seventh-graders.

Sister Canice was forty-four years old, a scholarly type who had joined the convent in 1932. When she was growing up her relatives would say, “She’s cut out for teaching.” Reading was Sister Canice’s hobby, and she preferred the classics; Dante was among her favorites. After literature she had a great love of history, especially Irish history, which she had picked up from her late father, a Chicago police captain. Both her parents had been killed two years earlier in a car accident involving a drunken driver. Following this personal tragedy, Sister Canice consoled herself with prayer, and the sisters and children of the parish had become her new family.

Next door, in Room 210, in the middle of the corridor, Sister Mary Seraphica Kelley was also preparing for the school day. Compared with some of the other nuns, her classroom demeanor was considered moderate. She enjoyed teaching the younger children and looked forward to the arrival of her fifty-seven fourth- and fifth-graders.

The lines on Sister Seraphica’s face made her look older than her forty-three years. Just two months earlier she had celebrated her silver jubilee as a nun. She had first come to Our Lady of the Angels in 1936, as a young teacher straight from the convent. She was later sent to Hollywood where she taught children of movie stars and entertainers. After several years on the West Coast, she came back to the Midwest to serve as principal of a Catholic grade school in DeKalb, Illinois, eventually returning to Our Lady of the Angels to complete the circle of her teaching life that had begun in Chicago.

Next door, at the west end of the corridor near the front staircase, Sister Mary Clare Therese Champagne was contemplating new Christmas decorations for Room 212. Of all the sisters in the parish, she was considered the artist and enjoyed decorating the school’s bulletin boards according to significant world events or seasons of the year. She kept an artist’s easel with paper at the front of her classroom and often would have her fifty-five fifth-graders use it rather than the chalkboard to figure their math problems.

Sister Therese had been reared in New Orleans where, before joining the convent, she had once been a Mardi Gras queen. She was pretty, twenty-seven, and spoke with a Southern accent that sometimes made the children giggle. She had an unhurried manner about her and a delightful sense of humor that endeared her to the other nuns and the children. Her good looks had turned the heads of more than a few male parishioners. She was, in the words of one parish priest, “a real knockout.”

THE THERMOMETER WAS sitting at twenty degrees when the bell inside the school began ringing at 8:40 a.m. Outside a morning ritual was already under way. Parents and relatives were arriving with children in tow, seeing their youngsters safely to school. The streets and sidewalks around the old school swelled with pedestrians. Patrol boys set up wooden horses on Iowa Street to keep traffic from clogging the building’s front entrance, and a couple of priests were standing outside the rectory, next to the flagpole, talking with mothers and fathers. Priests in the parish always made sure one or two of them were on hand in the mornings to stand watch outside, just in case any boys had ideas of starting a fistfight. More times than not, though, the men were in place simply to greet the children, to give them a wink and say hello. And though the priests didn’t know all the kids by name, certainly they knew their faces.

The students were toting books and folders, and those living farthest away carried lunch boxes. They marched dutifully through the school’s front doors, headed for classrooms they would occupy until the school day ended at three o’clock. Once out of the cold, the children doffed their caps, scarves, and mittens, and hung up their coats and jackets in clothes closets and on coatracks set in the hallways and narrow corridors.

The youngsters were attired according to Catholic school regulations. Boys wore dress shirts, dark pants, and ties. Girls dressed in blue or white sweaters, white blouses and jumpers, and blue plaid skirts. The school sweaters were embroidered with the letters “OLA,” an acronym the kids—when safely out of earshot of their nuns and lay teachers—referred to as “Old Ladies Association.”

A number of desks in the classrooms were empty that Monday. Colds, flu, and other childhood ailments had taken their usual toll on the school’s attendance record. And because it was the first day after a cold holiday weekend, there seemed to be more absences than usual.

One of the empty desks in Room 212 belonged to Linda Malinski, a ten-year-old fifth-grader with long blond hair and hazel green eyes. Linda and her older brother Gerry, a sixth-grader, awoke that morning with colds, and their mother, Mary, decided the children should stay home from school.

The Malinskis’ conversion to Roman Catholicism had come a year and a half earlier when the family was visited by a nun canvassing the neighborhood. The process was hastened when a parish priest, Father Alfred Corbo, persuaded the children’s father, Nicholas Malinski, to rejoin the church he had left in his youth. Nicholas and Mary were soon remarried in Our Lady of the Angels Church, and all six of their children were baptized in the Catholic faith.

Nicholas Malinski became a devout Catholic, and he and his wife wanted their children to attend parochial schools. In the fall of 1958 Nicholas Jr., the oldest of the Malinski children, was enrolled at St. Benedict’s High School, and Gerry and Linda transferred to Our Lady of the Angels. A younger daughter, Barbara, was denied admission because of overcrowding in the first grade. Instead she was enrolled in Ryerson public elementary school, across the street from the family’s home on North Lawndale Avenue.

Linda Malinski was a cheerful, happy girl with a bright disposition. She was a joy to her parents and helpful at home. And though she had acquired many of the playful mannerisms of her older brothers, she fell short of being a tomboy.

During the dark, early morning hours of that same Monday, Mary Malinski awoke in the stillness of the family’s home to the sound of someone crying. Outside it was chilly and silent. She listened intently, wondering to herself if she had in fact heard one of her six children cry out.

“Mommy?”

Now certain she had not imagined the muffled sobs, Mary arose and quietly crept past the children’s beds. Linda awoke with a start.

“Mommy,” Linda cried. “I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.”

Linda was choking on a nightmare. She dreamed of a fire and imagined that smoke was filling the family’s tiny apartment. Mary assured her daughter that everything was all right, that there was no fire. Linda suffered from asthma, and her mother figured the ailment was responsible for the girl’s coughs and labored breathing. But what Linda said next would later cause Mary to believe her daughter had had a premonition of the disaster that was to occur later that day.

“Mommy,” she cried. “I hear people screaming.”

Mary was concerned. She stayed at Linda’s bedside and comforted her daughter back to sleep.

Later that morning, after school had already begun, Linda told her mother she felt better and wanted to attend afternoon classes. When Mary took the temperatures of both Linda and Gerry, the readings showed normal, and she told the children they could join their classmates after lunch. The decision would haunt Mary Malinski for years to come.

As Linda prepared for school, she took great pains in fixing her long blond hair, a task usually performed by her mother.

“Mommy,” Linda asked, “does my hair look all right?”

Mary looked down at her daughter and smiled. “You look like an angel.”

AFTER LUNCHEON RECESS, the schoolchildren returned to their classrooms for the final two hours of study. Up to now the school day had passed uneventfully; the youngsters sat at their desks and endured the normal routines of reading, writing, and figuring.

Inside Room 206, tucked away in the annex on the second floor between the school’s north and south wings, lay teacher Pearl Tristano was readying her fifth-graders for their end-of-day chores. Tristano, a dark-haired twenty-four-year-old, was unmarried and lived at home with her parents in suburban Oak Park; she had been teaching at OLA for some time and was one of nine lay teachers on the school’s staff.

Sometime after 2:20 p.m., as the school day drew to a close, Tristano assigned two boys in her room to the daily task of carrying wastebaskets down to the basement boiler room. There they dumped the refuse into large metal bins so the janitor could burn it later in an outside incinerator. Their errand completed, the boys returned to the classroom and took their seats. Earlier Tristano had also excused from the room another boy—a bespectacled, blond-haired youth who asked to use the lavatory. This boy also returned a short time later and, with his classmates, sat down to resume his last-minute studies.

There was nothing unusual about these closing minutes of the school day, and nothing would be made of these temporary absences from Tristano’s classroom for some time. In fact, there was much movement in the normally deserted hallways of the school that afternoon: boys leaving their rooms to empty wastebaskets in the basement or stepping outside into the courtway to clean erasers; a girl walking to the convent to attend a music lesson; another girl going into a seventh-grade room to pick up a homework assignment for her sick sister; several boys leaving their rooms for neighborhood sidewalk patrol.

Unnoticed, something else was occurring that afternoon in an isolated, seldom-used corner of the school basement.

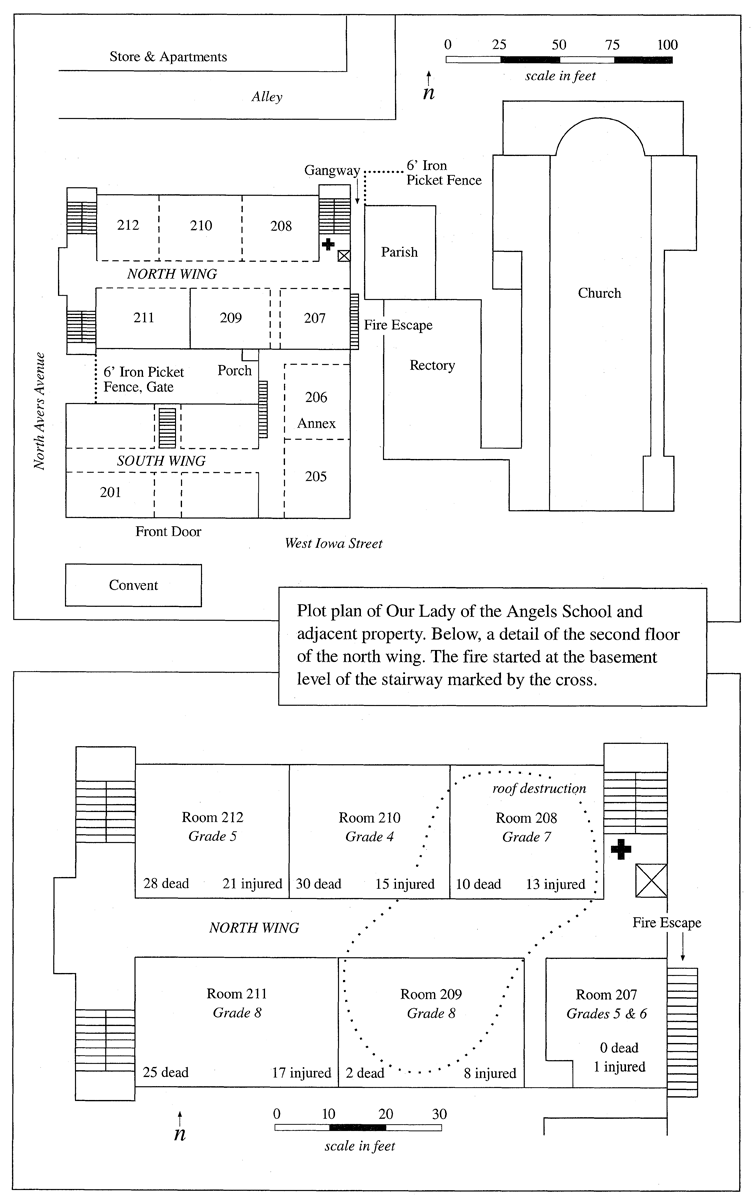

Located in the north wing, at the bottom of the building’s north-east stairwell, beyond a door that was only steps from where students were emptying their wastebaskets in the boiler room, a fire in a cardboard trash drum had been burning for several minutes. And though the exact time of the fire’s ignition would never be fixed to the precise minute, the date of its occurrence would soon be etched in the dark ledger of the nation’s terrible tragedies.

After consuming refuse in the container, the fire smoldered from a lack of oxygen, elevating temperatures in the confined stairwell. Suddenly, when a window in the basement broke from the heat, a fresh supply of air rushed in, and the deserted stairwell turned into a blazing chimney. Without a sprinkler system in place to check their advance, flames, smoke, and heat roared upward, feeding on the old wooden staircase and bannisters, melting asphalt tile covering the stairs.

On the first floor a closed fire door blocked the fire’s path. But no door was in place on the second floor. Consequently heavy black smoke and superheated air began pouring into the second-floor corridor. Lurking behind the smoke, flames crept along, feeding off combustible ceiling tile, painted walls, and varnished hardwood flooring.

At the same time hot gases from the fire entered an open pipe shaft in the basement stairwell and flowed upward into the cockloft between the roof and ceiling of the school. Flames erupted as well in this hidden area directly above the six north-wing classrooms packed with 329 students and six nuns. The out-of-control blaze was now raging undetected through the school, devouring everything in its path, cutting off escape for the unsuspecting occupants.

Despite the intensity of the fire, several minutes passed before anyone realized the school was ablaze. Two teachers wondered why the building seemed excessively warm, but they mistakenly assumed the janitor had overstoked the furnace. Finally a chain of events occurred alerting the entire school to the danger at hand.

THE FIRE IN THE SCHOOL was discovered in close sequence by several people, though no one at the time realized that this discovery would turn into a race against death.

School janitor Jim Raymond was one of the first to notice that something was wrong. Sometime before 2:30 p.m., Raymond was walking west on Iowa Street, returning to the school from a job in a nearby parish property on Hamlin Avenue. As was his habit, when he reached the rectory he turned right and walked north through the narrow gangway separating the priests’ house and the rear of the school. He was headed for the school’s boiler room, and as he approached the building’s northeast corner, he noticed a faint wisp of smoke.

Puzzled at what could be burning, Raymond quickened his pace. When he moved toward the corner of the building, he was startled to see a red glow coming from the frosted window pane near the back stairwell. He retreated into the gangway and ran through a door leading down into the boiler room. Once inside, Raymond peered between the two cylindrical boilers and saw that the interior door leading to the stairwell was slightly ajar, and that a fire was raging upward on the other side. The fire appeared to be out of control. It was too big for Raymond to fight himself.

Fifth-graders Ronald Eddington and James Brocato were in the boiler room, emptying waste paper baskets from Room 205, when the janitor appeared. The noisy boilers had masked the sound of the fire in the stairwell, and the boys apparently did not realize that a blaze was burning only a few feet away. They were startled to see Mr. Raymond so excited.

“Go call the Fire Department!” he yelled to them.

The boys looked at each other, puzzled. Then they caught a glimpse of the fire.

“Let’s get out of here!” Ronnie shouted.

The janitor left too. He raced back outside to the rectory next door. When he stormed into the residence, Nora Maloney, the silver-haired, thick-brogued housekeeper was standing in the kitchen, preparing a sauce for the evening meal. She jumped when the back door slammed.

“Call the Fire Department! The school’s on fire!” Raymond shouted to her.

Nora Maloney was unaware of the situation beginning to unfold only a few yards from where she stood. She set her ladle down on the stove and walked over to a small window above the sink that faced the back of the school. She looked out and saw smoke. When she turned around to respond, Raymond was gone. He had already run back into the burning school; inside were four of his own children.

ELMER BARKHAUS, an amiable, sixty-one-year-old part owner of a glue company, turned his black Buick off Augusta Boulevard and drove south on Avers Avenue that afternoon. He spent most of his working hours traveling, selling his wares to local floor-covering contractors, and he had a few more stops to make before starting the long drive to his home on the city’s South Side.

As Barkhaus neared Iowa Street, something caught his eye. He slowed his car to a crawl and peered into the alley just north of the maroon-brick building of Our Lady of the Angels School. Smoke was pouring out the rear stairwell door.

Barkhaus thought a second. Stay calm. Don’t get excited. He had to be careful. The ulcers in his stomach were fragile. He pulled over to the curb, then looked for a fire alarm box on the corner.

He didn’t see one; not all Chicago schools had them. He spotted a small candy store next to the alley directly north of the school. There must be a telephone inside.

Barbara Glowacki, the store’s plump, twenty-nine-year-old owner, was sitting in the back kitchen, next to the living room, riffling through the newspaper. Duke, her German shepherd, was barking as Joseph, her three-year-old, pedaled his little blue car around the apartment.

Barbara was waiting for school next door to let out in another twenty minutes, when her store would be invaded by youngsters stopping in to spend their nickels and dimes on the array of candy she had for sale. Helena, her seven-year-old, would be among the kids.

Only two years earlier she and husband Joseph had become naturalized citizens of what she fondly called her “promised land.” The couple had met and married in postwar Germany. Being Polish, Joseph had not been well received in Germany, and Barbara, a German, had been unwelcome in Poland. After shifting around, the couple followed thousands of other displaced Europeans, emigrating to Chicago in 1950.

The front door rattled. Barbara looked up from her TV listings, her view blocked partially by a refrigerator. She saw it was a man, someone she had never seen before. He looked worried, nervous. Perhaps he was ill. She went to see.

“Ma’am,” he said, “you got a phone?”

There was a phone in the back, but Barbara thought it unwise to let the stranger use it, not when she was home alone. She was leery.

“No,” she replied, “I don’t have a public telephone.”

Barkhaus wheeled around and headed for the door. Before running out he turned back to the woman at the counter. “The school next door is on fire!”

The salesman darted outside and across the street to a two-flat building where he began ringing the doorbells of both apartments, hoping to find a telephone.

Barbara was skeptical. Why would he say such a thing? He must be mad. Still, she was curious. Shoving her hands in the pockets of her sweater, she walked outside, shivering as she stepped into the cold. She took a few steps and turned left into the alley between her store and the school. Everything seemed normal. She took a few more steps. Then she saw it.

A tongue of bright orange flame was curling up over the transom above the back stairwell door. “Oh my God!” she yelled.

Barbara clutched herself, then pictured Helena, whose classroom was on the first floor. She turned around, hoping to see someone, anyone. She looked for the stranger. He was gone. She turned back to the stairwell. Smoke and flames pouring out the doorway were all that met her frantic glances.

For the moment Barbara was alone in the cold, quiet alley. She looked up at the school windows. The building was filled with children, but she heard no fire alarm. Suddenly her fears were realized.

They don’t know!

Barbara couldn’t move fast enough. She ran back to her building and crashed through the front door, knocking down a candy display in front of the store. Her mind was scattered. Everything was a blur except the black telephone sitting on the kitchen table.

When Barbara reached the kitchen, she picked up the phone. Her hands were shaking and she was out of breath. She thought “Fire Department” but drew a blank; she couldn’t remember the seven-digit number. Instead she dialed the operator.

“Give me the firemen, quick!”

After she was connected, a man on the other end responded: “Chicago Fire Department.”

“Our Lady of the Angels School is on fire. Hurry!”

“Somebody called in already. Help is on the way.”

The fire alarm operator’s voice was cool and reassuring. For the moment it had a calming effect on Barbara.

FRANKIE GRIMALDI raised his hand.

“Yes?” Miss Tristano asked.

“May I go to the washroom?”

“You may.”

Frankie got up from his seat in Room 206 and walked out of the classroom. Something strange caught his attention. There was smoke in the hallway. When he turned, Miss Tristano was right behind him. She too had caught a whiff of the smoke.

“Get back in the room,” she ordered the boy.

Following Frankie back inside, Tristano looked to her students. “Stay here,” she said. “I’m going next door.”

When Tristano returned to the hallway, the smoke had grown darker and hotter. She walked next door to Room 205 to alert Dorothy Coughlan, the lay teacher there.

“What should we do?” Tristano asked, aware of the strict rule that permitted only the mother superior, the school’s principal, to ring the fire alarm.

“I’ll go to the office,” Coughlan said. “You stay here.”

When Coughlan reached the principal’s second-floor office in the middle of the south wing, she found that the superior, Sister Mary St. Florence Casey, was substituting for a sick teacher in a first-floor classroom. By the time Coughlan returned to her own classroom, the smoke entering the tiny annex corridor had worsened. She and Tristano decided not to wait for an alarm and instead to evacuate their classes.

Tristano reentered her room. “Everybody get up,” she announced to her students. “We’re leaving the building.”

The two teachers lined up their pupils in fire-drill formation, then marched them into the corridor and down a set of stairs in the south wing that led to the first floor. Once downstairs, the two groups filed through doors leading to the Iowa Street sidewalk. When Tristano reached the first floor behind the children, she flipped the switch on the wall-mounted fire alarm located at the bottom of the stairway. Nothing happened. She darted outside. Coughlan was yelling. “Take them to the church. I’m going to the convent. I’m calling the Fire Department.”

Obeying her older colleague, Tristano hurried the two classes into the parish church next door. Then she returned to the school and the fire alarm. The alarm on the wall resembled a light switch and was almost six feet off the floor. When Tristano flipped it the second time, the audible buzzer started sounding in the school. But the alarm was merely a local one—it rang only inside the school; it did not transmit a signal to the Fire Department.

It was now 2:42 p.m. Nearly eight minutes had elapsed since Tristano first noticed the smoke.

A MILE SOUTH of Our Lady of the Angels School, the merchants along Madison Street were looking forward to the holiday shopping season, optimistic that sales would improve over the recession-ridden Christmas of 1957. They were already dressing up their storefronts and the streetlights along the avenue with decorations in green, red, silver, and gold.

Mary Stachura picked up a packet of invoices and looked around the crowded back office of Madigan’s department store. She was happy to have this, her first Christmas job, now that both her sons were in school. And the fashionable ladies’ store, located in the midst of the area’s main shopping hub—Crawford Avenue and Madison Street—was just minutes from home.

Mary loved the family atmosphere in the neighborhood. She and her husband, Max, could reach out and almost touch the bricks of Our Lady of the Angels Church from their two-flat on Hamlin Avenue. They never had an excuse for being late for Sunday Mass.

Max’s parents lived upstairs and last year began teaching Polish to Mark Allen and John, both students at Our Lady of the Angels. Proud of their European heritage, the elder Stachuras, like many Chicago Poles, hoped that heritage would be treasured by their grandsons.

Mark was tolerant of his language lessons, but one aspect of his ancestry bothered him: his blond hair. “Why can’t I have black hair like all the other kids?” he would grumble.

His schoolmates were mostly dark-haired Italians, and Mark hadn’t seen them in a week; he’d been home ill. In his eagerness to get to school that morning, he’d almost forgotten to kiss Mary good-bye.

“Bye, Mom,” he had said, planting a kiss on her cheek. Running down the short flight of stairs, the fourth-grader had been singing. His glee may have been due in part to being over his recent minor illness, but for some reason Mary had a feeling of apprehension.

It was going on 3 p.m. when she looked up at the clock and thought of Max. He’d soon be picking up their children, and at five o’clock they would meet her and go to dinner. Later they would take the boys to see Santa Claus.

Mary was fingering through invoices when a dissonant sound began to mingle with the generic, piped-in Christmas music. At first she didn’t notice it. But soon the wailing sirens grew closer, louder, demanding to be heard.

“There must be a big fire somewhere,” Mary thought.

Instinctively she clutched the gold crucifix around her neck.

IT HAD BEEN only seconds since the calming voice of the fire alarm operator had assured Barbara Glowacki that help was on the way. But when she ran back outside, the scene in the alley had changed dramatically. The single flame she had first seen in the school doorway had grown into a raging inferno. The windows of the second-floor classrooms had been thrown open and were filling with dozens of terrified, familiar faces. Some were screaming, gasping for air. Black smoke was billowing over their heads. The little faces in the windows seemed to be piled on top of one another.

Barbara trembled. “Lord have mercy!”

The kids were screaming to her. “Get me out of here! Catch me!”

Some of them knew her name. “Barb! Help us! Help me!”

Sister Mary Seraphica was leaning out the middle windows of Room 210, hacking and coughing. She spotted Barbara. “Please help, help!” she screamed. “Call the Fire Department!”

Barbara yelled back. “Why don’t you get out?”

“We can’t. We’re trapped.”

“Hold on, sister! Help is on the way! The Fire Department is on the way!”

The nun kept on screaming and Barbara wondered why she and the children didn’t leave their rooms and run down the stairs. She didn’t know the fire and smoke had completely engulfed the upstairs corridor, making escape through the hallway seem impossible. She ran over to the side door near the front of the school to see if it was jammed shut. When she pulled on it, the door opened an inch or two, but black smoke inside pushed out and drove her back. The smoke was too much; it was burning her lungs.

Suddenly Barbara was overwhelmed by fear. She remembered her daughter Helena, whose second-grade classroom was on the first floor.

“My child! Where’s my child!” she screamed.

She scurried around the corner and ran through the school’s front door on Avers. A nun was leading a group of frightened students out of the building. They were filing out fast, one after the other.

“Oh sister,” Barbara cried. “They can’t get out. They can’t get out.”

The nun was calm; she didn’t realize what was happening upstairs. “We all got out. We all got out.”

Barbara ran back into the alley. All of the windows were open and children were hanging from the sills. They were throwing books and shoes and screaming for rescue. She ran back and forth, yelling up to them. “Help is coming! Help is coming!”

Then … children began jumping from the windows, landing on the pavement twenty-five feet below.

Still no firemen. The alley was filling with people. A woman ran up to Barbara.

“Why don’t the firemen come?” they asked each other simultaneously.

It had been only a minute since Barbara called the Fire Department, but it seemed like an eternity had passed.

Youngsters were landing all around. Some of them had been burned. Others were bleeding. A few got up and hobbled away. Still more lay motionless and silent. They looked broken up. Barbara began dragging kids out of the way, setting them against the wall of her adjacent store.

Some youngsters clearly had broken bones—arms and legs—and Barbara kept thinking, “Isn’t it wrong to move injured people?” But she had no choice; she had to make room or the injured would be struck by other falling bodies. She grabbed one boy whose leg was dangling over the other. He was big and heavy, almost too much for her. Still, she found the strength. She grabbed under his armpits and yanked, dragging him out of the way.

Barbara placed six youngsters against the side of her building. Their faces were blistering and swelling up. On some, their clothing was smoldering. Barbara ran into her store and filled a pot with water. Returning to the alley, she began pouring water over the children.

She walked some of the youngsters into her store, out of the cold, shielding them from the awful sights outside. She put them in the kitchen and bedroom, setting them in chairs and laying them in her bed. She grabbed her rosary and handed it to a girl. “Pray for the children,” Barbara told her.

Then, once again, thoughts of her daughter flashed through her mind: “Where is my Helena! She hasn’t come out.”

Barbara rushed back outside, her eyes searching. She brushed past a nun carrying an injured child. She saw Monsignor Cussen, his face contorted in horror, running through the alley, crying. Finally, she spotted Helena’s nun in the street.

“Where is my child? She didn’t get out.”

“She did get out,” the nun screamed. “Someone grabbed her and took her to one of the houses.”

STEVE LASKER saw the plume of smoke in the distance as he drove along Grand Avenue. He was trying to warm up. The twenty-eight-year-old newspaper photographer had just completed an assignment outdoors at a fire extinguisher company. The firm had conducted a test, dropping an extinguisher from its roof to prove that its product wouldn’t explode upon impact. The test was in response to a charge that one of its units had done just that.

The smoke in the sky to the south was growing thicker and blacker.

Looks like a good fire, Lasker thought. He grabbed the microphone on his two-way radio and called the Chicago American city desk. “Do you have a fire working somewhere on the West Side?”

The day city editor came back. “Don’t know anything about it.”

Just then the police radio in Lasker’s car started blaring. “Send all the help you can! They’re jumping out all over!” It was the excited voice of a lone patrolman, the first to arrive at the school.

“Attention, cars in the 28th District,” responded the police operator. “Assistance is needed at Our Lady of the Angels, Avers and Iowa.”

Lasker stepped on the gas and headed toward the smoke.

MARIO CAMERINI, a friendly twenty-year-old who had grown up in the neighborhood, emerged from the back door of the church basement carrying a case of empty Pepsi bottles. In his part-time job as assistant janitor, he helped out in the church, and on Mondays he always returned the empties from the week before.

Mario was walking into the alley, on the way to Barbara Glowacki’s store, when he heard the commotion. He looked up to the windows of Room 208, next to the back stairwell, and saw dozens of seventh-graders jamming the open spaces. Smoke was pouring from the windows. Only a few years ago Mario had been a student in that same classroom. He recognized some of the faces of the youngsters who were screaming down to him for help. He set the bottles down and ran to the garage behind the rectory. There were ladders stored inside.

MAX STACHURA was napping on the front-room couch facing the television set when he looked at his watch and saw that it was almost time to pick up the boys at school. As a driver for United Parcel Service, Max worked odd hours. He was catching up on his sleep.

Max arose and stepped into the kitchen, putting water on for coffee. Smoke wafted past the back window. When it cleared for a moment, he was startled to see that it was coming from the school. Like many parents, the Stachuras had been concerned about fire in the old building. Only a few weeks before, a small blaze had erupted in the school’s basement, just papers and rags. The family consoled Mark, who had come home that day worried.

“Always listen to your nun, and the Fire Department will help you,” Max had told him. And to Mary: “We live so close, if there’s any big trouble we’ll get them out.”

Following his own advice, Max grabbed his jacket and ran out the back porch, down the stairs, and into the alley where he saw Mario struggling with a ladder in the garage.

“C’mon,” Max yelled. “I’ll help you.”

The two men picked up the extension ladder used to put up screens and hurried to the burning school. They heaved it up against the wall, raising it to an open window of Room 208. As soon as the ladder touched the sill, seventh-graders began crowding and pushing in a rush to get on it. They started climbing down.

Max felt a momentary sense of relief. But when he glanced over to the smoke-filled windows of the classroom next door, his heart sank.

“That’s Mark’s room!” he screamed.

Sickening black smoke was pouring over the little faces of students who fought for every inch of space in the small, dark openings. The fourth-graders’ heads barely cleared the sills. Mark’s face had to be among them. Kids were climbing over one another. The windows were filling with teetering children. Then the pushing and jumping started.

Max fretted. “Where’s Mark?”

Finally he spotted his son’s little blond head bobbing up and down in the crowd.

“Daddy!” the youngster shrieked. “Help me!”

“Stay there!” Max yelled. “Don’t jump!”

Max looked around. He was surrounded by chaos. The fire alarm was ringing over the shouts and screams. Bodies were dropping and landing all over, hitting the pavement and crushed rock with sickening thuds. One man caught a girl whose hair was on fire. He used his coat to smother the flames. Another man standing nearby was being battered to the ground by more falling bodies. Men and women were dragging limp children away from the burning building. Some were badly injured, screaming. Others were deathly still.

“This is crazy! They’re killing themselves,” Max thought.

He looked back up. Mark was getting ready to jump too.

“No, son! Wait! I’ll get you down!”

He ran to his garage in the adjoining alley. Fumbling for his keys, he unlocked the overhead door, grabbed a paint-spattered ladder, and ran back to his son’s window at Room 210. The cloud of black smoke pouring from the school was turning darker and denser by the second. The whole place looked like it was ready to explode.

Mark was still struggling at the windowsill when Max returned with the ladder.

“Hold on son! I’m coming!”

The father’s heart was pounding wildly. He was nearly out of breath when he flung the ladder against the wall. His momentary elation turned sour. The ladder was too short.

In fact the north side of the building was now dotted with home ladders perched against the school’s outer brick wall. All the ladders were too short; children hanging from the windows couldn’t reach them. The screams from above forced Max to refocus his attention on Mark’s position in the window.

His son called for him. “Daddy!”

The large man’s shoulders slumped, and tears began to fill his eyes. The ladder had been his only chance. What else could he do?

“Mark!” he yelled. “Jump! I’ll catch you!”

Mark’s eyes never left his father. The little fourth-grader tried one last time to pull himself over the windowsill. But just as his elbows touched the ledge, a whoosh of flames crawled up and pulled him back down into the room. Max watched in horror as his son disappeared in the smoke. He was standing in the alley, arms outstretched, helpless. It was the last time he would see Mark alive. The crushing grief dropped him to his knees. He was too late. Despite the nearness of his home, it wasn’t close enough.