FIREFIGHT

AT CHICAGO’S MAIN fire alarm office, Monday had been unusually quiet. Located in City Hall in the heart of Chicago, the office was responsible for dispatching all city fire equipment stationed north of 39th Street. Inside the big, airy room, a huge electric wall map pinpointed the location of every fire station in the city. Most of its lights were on, indicating fire companies were in service, in quarters. For most of the day the keys on the master telegraph had been silent, with only a few fires being logged since the shift had begun at eight o’clock that morning.

At 2:42 p.m. a loud buzzer signaled an incoming emergency call. Senior fire alarm operator Bill Bingham was sitting at the switchboard. He picked up the phone. “Chicago Fire Department,” he answered. His tone was calm, businesslike. A woman’s voice was on the line. She was excited, heavily accented, almost unintelligible. It was Nora Maloney.

“There’s a fire in our building,” she cried. “Send help!”

Experience had taught Bingham how to pry out the location. “Where are you, ma’am? Where exactly is the fire?”

Maloney was confused, her mind racing. “Our Lady of the Angels. On Iowa. 3808 Iowa.”

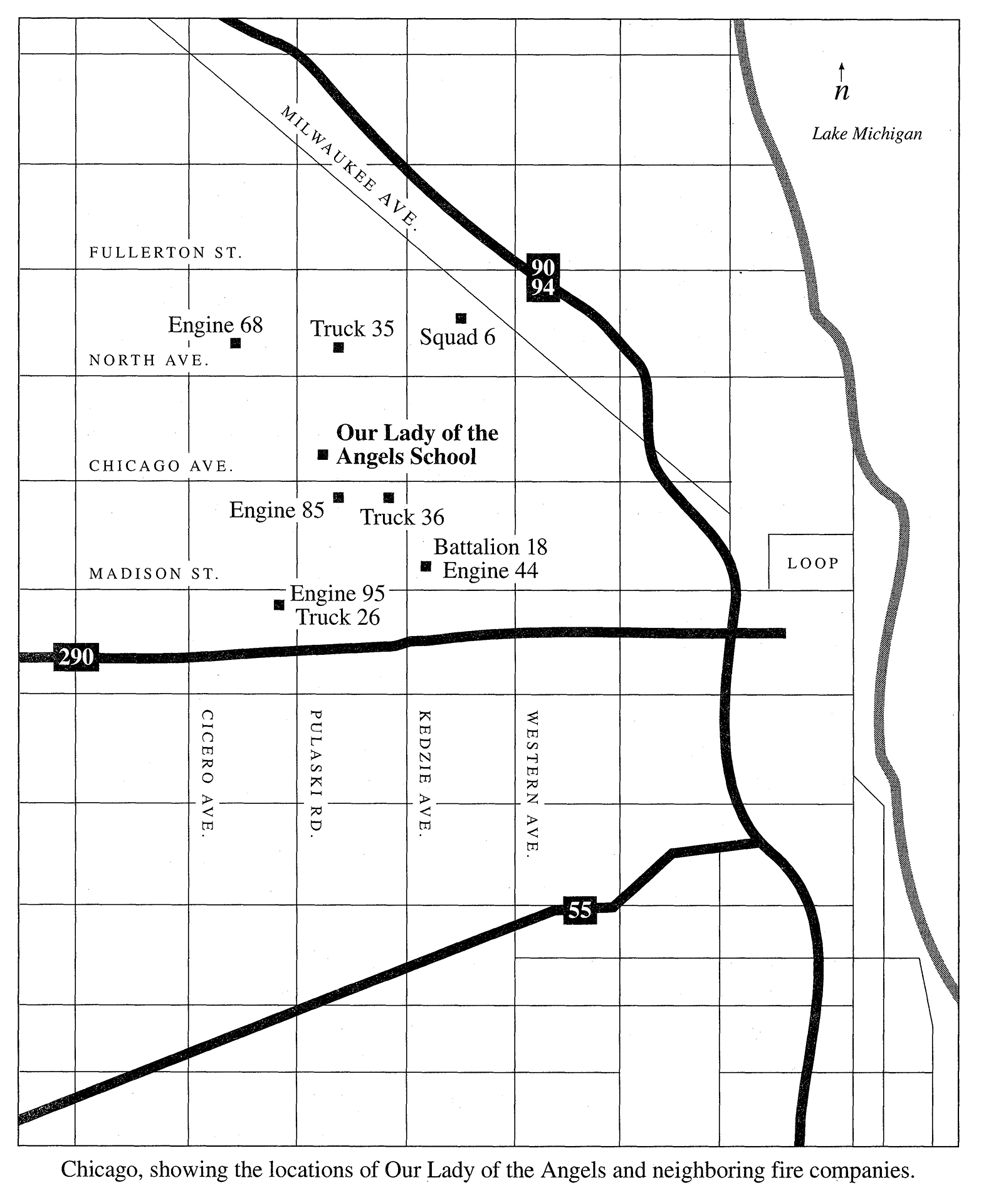

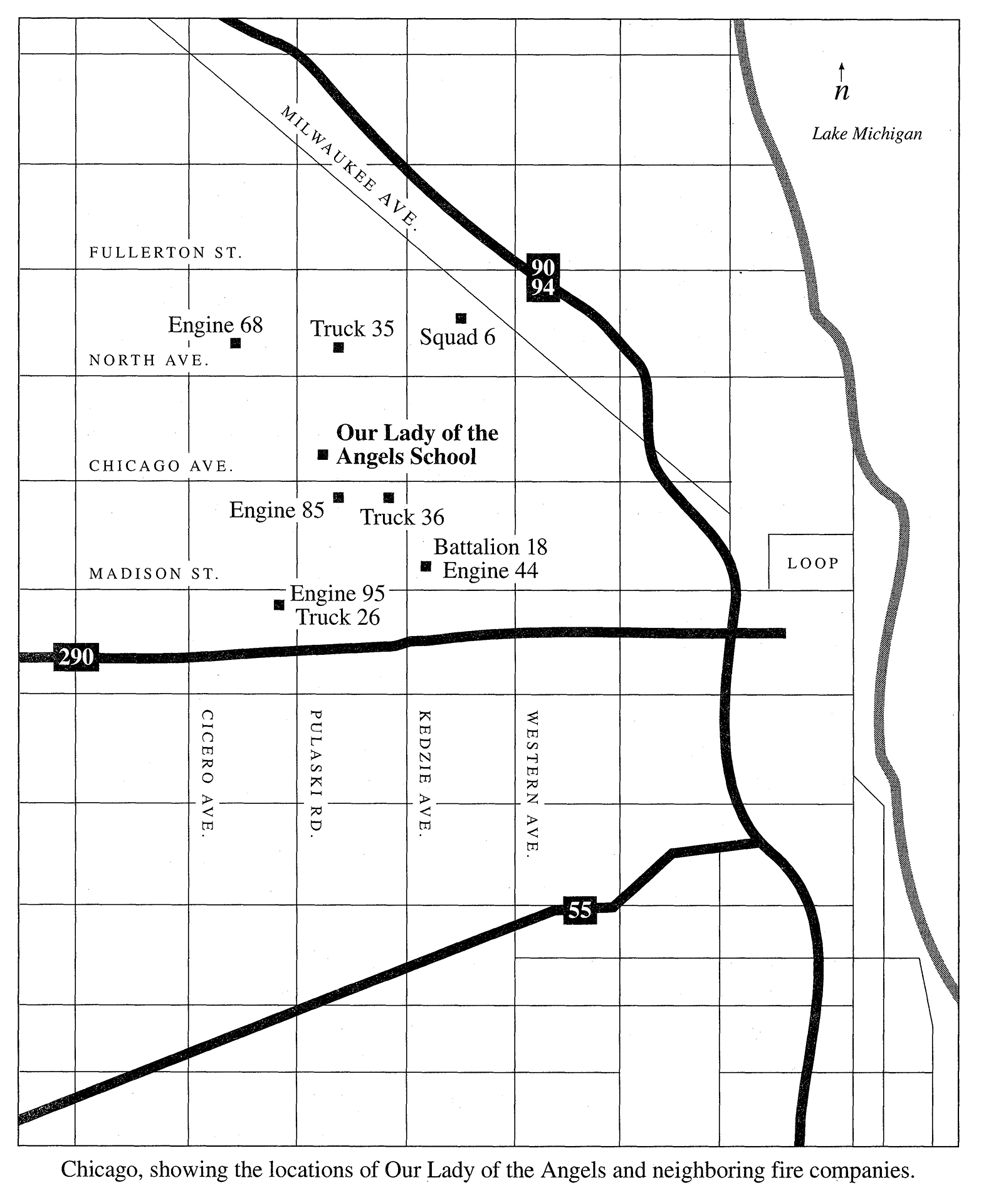

The location she gave was that of the rectory. Unknown to Bingham, the burning school was around the corner and half a block away, at 909 North Avers. As soon as he had an address, Bingham set down the phone and pulled the run card showing the nearest fire companies. Engine 85, Hook and Ladder 35, Rescue Squad 6, and the 18th Battalion chief were due to respond. Fire Patrol 7, a salvage unit operated by insurance underwriters, also was assigned. Another operator at the alarm board started flipping switches, cracking the intercom to transmit the “still alarm” (Fire Department jargon for an alarm received by phone) to the companies housed five miles away on the city’s West Side.

Almost immediately other calls began pouring into the office. Bingham answered one call from a woman who “sounded like she was describing the Hindenburg disaster.”

The mood in the alarm office was growing tense. “Sounds like we’ve got something,” said chief fire alarm operator Joseph Hedderman. He looked up the nearest fire alarm box—number 5182—located one block east and one block south of the school, at Chicago and Hamlin avenues. Following standard procedure, he began tapping it out on the telegraph, transmitting the box alarm to every firehouse in the city. In more than a hundred fire stations, blue-shirted firemen stopped what they were doing to count the toll of the bell as 5-1-8-2 rang in four times over the ticker, punching red dots on a sheet of paper tape, turning on lights and setting off alarm bells for the companies that were due to respond. Three more engines, two more hook and ladders, another battalion chief, and the 2nd Division marshal were now pulling out.

FIVE BLOCKS AWAY from the burning school, inside the quarters of Engine 85, Lieutenant Wojnicki was sitting on watch at the front of the firehouse. Since he had come on duty the company had answered two alarms to extinguish small rubbish fires, one in the morning and one around noon. Now, as the brisk December day moved to mid-afternoon, there was little noise or movement in the station save for a mild debate in the kitchen over the merits of the evening dinner menu. The repartee was suddenly interrupted when an operator’s voice crackled over the loudspeaker:

“ENGINE 85, STILL ALARM FIRE, 3808 WEST IOWA.”

Wojnicki scribbled the address on a small chalkboard, then picked up the watch desk’s “joker” phone, which brought him into contact with the downtown office. “Eight-five,” he repeated, “3808 West Iowa. Fire.”

His response was departmental procedure ensuring verification of the alarm’s address: 3808 West Iowa Street, a run that would take two minutes.

The lieutenant rang the house bells, then took up his position in the front cab. Engineer Henry Holden was already behind the wheel of the red-and-black pumper, revving the motor, waiting for the company’s three remaining firemen to pull on their boots and coats and jump onto the rig’s backstep. Thirty seconds later the engine pushed out into the wintry street.

AT THEIR downtown firehouse, Richard Scheidt and his fellow firefighters were standing in front of the apparatus bay, peering out a window of the overhead door as groups of pedestrians walked along Dearborn Street. The firemen were too far away to hear the sirens. But they knew something was happening.

Whenever a fire was reported, the main fire alarm office alerted all eighty-seven North Side firehouses, letting them know equipment was being sent out. The alert came into each firehouse over the “sounder,” a Teletype instrument using a numerical code.

At 2:42 the sounder began its familiar clacking. The firemen stopped to listen:

“5-5-5-8-5”

“5-5-5-3-4-5”

Engine 85 and Truck 35 were being “stilled-out” to a fire.

One of the officers on watch was curious about the location. He picked up the “joker” to listen: “Thirty-eight-o-eight West Iowa. A fire.”

He repeated the address to Scheidt and the others standing around the desk.

“Must be the church,” said one fireman who lived in the same West Side neighborhood. No one took particular notice. It was just another still alarm, one of dozens that Chicago firemen responded to each day. And the address was well out of Squad 1’s district—too far west. They wouldn’t even go on a 5-11. Besides, five-alarm fires were rare for such good residential neighborhoods.

The men returned to their thoughts, hands in pockets, awaiting their next alarm.

ENGINEER HENRY HOLDEN followed a direct route through the neighborhood toward Iowa Street. As Engine 85 crossed the intersection of Chicago Avenue a block away, the firemen could see smoke rising in the sky.

“We got a fire,” said Holden.

Wojnicki nodded. “Probably a garage.”

Based on the address given by the main office, Wojnicki figured the garage behind Our Lady of the Angels Church was ablaze. The smoke was black, like that given off by burning tar paper. But as the engine approached Iowa Street and as Holden swung left, past the church, the firemen knew immediately they had been given the wrong address.

Swarming in the streets and sidewalk outside the church and south wing of the parish school were hundreds of students, nuns, and lay teachers. Neighbors and parents were carrying injured and frightened children from the school. Other youngsters were leaning out the open second-floor windows overlooking Iowa Street.

After maneuvering his rig through the swelling crowd, Holden pulled to a stop in front of the school. Wojnicki could see he had an emergency on his hands, that more help was needed. He grabbed the microphone on the engine’s two-way radio. “Eighty-five to Main!” he yelled. “Give me a box!”

“You’ve already got a box, Eighty-five,” responded the operator in the alarm office, where telephone calls reporting the fire were now clogging the switchboard.

When Wojnicki ran around to the Avers side of the building, he saw plenty of smoke coming from the school, but no flames. Where is it? he thought. He had to find the source of the fire first, then get a line out and start water. He looked up. Children were throwing books and shoes out the windows, pleading for rescue.

“Goddammit,” he shouted, “stay up there! Help is coming!”

Holden was spotting the pumper at a fire hydrant on the corner when Wojnicki brushed past a harried clergyman pleading with the firemen to hurry. “Don’t worry, we’ll handle it,” he told Monsignor Cussen. The pastor had rushed over from the church hall on Hamlin Avenue, where he’d been helping the group of eighth-grade boys load clothes onto a truck destined for the Catholic Salvage Bureau.

Wojnicki ran a few more steps, stopping at the iron fence fronting the courtway between the school’s two wings. Smoke was pouring out the upper windows, and frightened students were crowding the open window spaces. They were screaming, getting ready to jump.

Suddenly Wojnicki heard someone shout, “They’re jumping,” and he ran a few more steps, turning into the alley north of the school. There he came face to face with the true horror of the moment. It was a sight that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Black smoke was billowing from every open space on the building’s upper story. Horrified parents were running back and forth, screaming as children at the windows were throwing out objects, hanging off the sills, dropping or hurtling themselves to the ground. Scores of inert bodies—children who had already jumped or had been pushed out the windows by classmates—covered the pavement. Wojnicki recognized a few of the kids at the windows. The youngsters’ faces were turning color. Some had clothing on fire. He had never imagined anything like it in his life. He was witnessing a nightmare.

“Jesus Christ!” he sputtered.

The fire had been burning for nearly a half-hour, and heat inside the classrooms had grown so intolerable that children were now plummeting out the windows two and three at a time. Old painting ladders had been thrown against the building, but most were too short. Students trying to reach them were dangling from the sills, hanging by their fingertips, dropping to the ground. The scene in the alley was now complete chaos, and only then did Wojnicki begin to comprehend the full extent of the disaster at hand.

As officer of the first engine company on the scene, he knew his priority was to get water on the fire as quickly as possible. He spotted flames shooting out the back stairwell door and figured it had to be the source of the fire. Pushing aside distraught mothers begging him to save their children, he decided to stretch a hose line to the burning stairway, hoping to cut off the flames there, then try and fight his way into the burning building.

When the lieutenant returned to the street, the engine’s soft-suction line had already been connected to the hydrant. Holden and another fireman, Ralph Clark, were pulling off the company’s twenty-four-foot extension ladder. “Over here! Over here!” Wojnicki yelled, motioning them to the alley.

On the upper floor of the north wing, three classrooms overlooked the alley. Room 208, with its forty-six seventh-graders, was in the back, next to the burning stairwell. Room 210 was in the middle and included fifty-seven fourth-graders. Room 212 was in the front, nearest the street, and held fifty-five fifth-graders.

As soon as Holden and Clark rounded the corner of the building, they caught sight of a boy hanging from the window ledge of Room 212. The men threw their ladder up against the wall. It was short by a few feet. Charles Robinson, another fireman from Engine 85, nonetheless managed to run up and pluck the youngster from the ledge, the first of several children he would bring down from the room.

Just then two firemen from Truck 35 appeared in the alley with a life net. Almost immediately youngsters began dropping into it. But the laddermen hardly had time to dump the big, round, metal-rimmed canvas before more bodies came plummeting down, some missing the net entirely.

Meanwhile Wojnicki and Holden had run back to the engine, and with the help of several civilians, the lieutenant and fireman Thomas Moore started leading out a two-and-a-half-inch hose line from the back bed of the pumper. The men dragged the heavy hose across the street, into the alley, stretching it all the way to the back stairwell. Once the hookup and hose layout were completed, Holden opened a discharge valve at the pumper, sending water to the other end of the line. Moore opened the nozzle and started attacking the flames, directing a heavy stream into the stairwell, trying to clear a path so the firemen could get inside.

The men were squatting behind the nozzle, throwing water on the flames, trying to inch their way forward. But the inferno in the stairwell continued to roar unimpeded. It was loud, crackling, out of control. The fire had gained too much headway. Passage up the stairs, at least for now, was out of the question. Moore redirected the stream down into the basement, hoping to cut off the chimney effect being created by the fire’s fierce upward draft.

It was then that Wojnicki began to piece it all together. Experience told him the fire had too great of a head start, that the firemen had been called too late. “Sonovabitch,” he cursed. Up above, flames were bursting out of the middle room. A grey-faced little fourth-grader, his clothing ablaze, stood on the ledge. Wojnicki caught a glimpse of him. He and Moore quickly swung their line around, spraying water all around the youngster, hoping it would force the boy to leap from the ledge, into the net.

“Jump, kid! Jump!” Wojnicki screamed.

FIRE COMMISSIONER Robert Quinn was in his City Hall office looking over a stack of blueprints spread across his desk when the telegraph register outside his door started its familiar pinging. He glanced up, counting the toll of the bell as Box 5-1-8-2 began ringing over the system.

He looked at his watch. It was 2:44.

“A still and box alarm fire at 3808 West Iowa Street,” a dispatcher was announcing over the Fire Department’s radio system. Something was brewing. The West Siders were getting some business. No need to worry, thought Quinn. Engine 85’s district was not an area where the department expected severe fires. Probably just a storefront. Maybe a two-flat.

He returned to his papers.

HOOK AND LADDER 35 was racing south from its Springfield Avenue firehouse one mile north of the school. Lieutenant Charles Kamin and his truck men were making good time. There were four traffic lights between the firehouse and the school, and each was green. Not once did his driver, fireman Walter Romanczak, have to let up on the accelerator.

When the still alarm was transmitted by the main office, the same urgent directive came across the speaker in the truck’s house: “TRUCK 35, TAKE IT IN, 3808 WEST IOWA.” The school was in the southernmost portion of Truck 35’s district, which extended south to Chicago Avenue. The company numbered five men, and its truck carried a full complement of ladders that reached twenty, twenty-six, thirty-six, and fifty feet in length. Its aerial, or main, ladder stretched eighty-five feet.

Three minutes later, as the long hook and ladder neared Iowa Street, Kamin could see a dark haze floating through the neighborhood. It was smoke, no doubt about it. He knew they had a “job.”

When Romanczak swung right onto Iowa Street, the truck men were met by the same chaotic scene that had greeted Engine 85’s crew a minute earlier. Kids were bunched at the upper windows overlooking the street, and hundreds of other frightened youngsters were streaming from the school’s ground-floor exits. Frantic parents and adults were running into the crowd, scooping up children, carrying them into the church and rectory next door. Based on the address given by the alarm office, coupled with the smoke pouring from the windows, Kamin assumed he was in the right spot. He leaped from the cab barking orders. “Start a ladder run-up!”

The firemen responded, pulling a twenty-six-foot extension ladder from the back of the truck, raising it to a window on the Iowa Street side of the building. Kamin started for the front door when something caught his eye. A man dressed in a plaid jacket was standing on the corner, jumping up and down hysterically. He was pointing and shouting. “This way! Over here. The fire’s over here!”

Kamin followed the man around to Avers and saw the calamity unfolding in the north wing.

Shit, he cursed. They were in the wrong spot. They would have to reposition. He ran back to the corner to summon his gang. “Pull the truck around!” he yelled to Romanczak. “It’s on Avers!”

Kamin ran back to the courtway separating the two wings. Immediately he saw panicky students crowding the smoke-filled windows. Scores of injured and dying children who had already jumped were lying on the pavement.

Time was running out quickly. The red-brick school, with its wooden interior and asphalt roof, was belching out smoke like a boiler. Kamin’s job was search and rescue. He knew he had to get inside the U to start laddering the windows. But still another delay was slowing his progress—the iron picket fence that blocked access into the courtway. The formidable seven-foot-high obstacle impeded the path of rescuers. Men from the neighborhood—grandfathers, fathers—were trying to break it down. Some were dressed in suits, others in overalls and work clothes. They were ordinary citizens showing tremendous strength. They were going crazy trying to push the fence in, to somehow get over it. One had located a sledgehammer and was swinging it feverishly at the locked gate. But it was no match for the fence. The dull, clanging raps bounced off with little effect. The gate wouldn’t budge. Kamin was getting agitated. He felt inept. “Goddammit!” he shouted.

Just then the hook and ladder came wheeling around, stopping in front of the north wing. Romanczak set the transmission in neutral, then pulled on the parking brake. When he looked up at the school, he could hardly believe his eyes. A boy leaped from a window and bounced off the pavement.

“Strip the truck! Strip the truck!” Kamin yelled.

The firemen pulled off a thirty-six-foot extension ladder and threw it over the iron fence into the courtway. Then they grabbed a second, twenty-six-foot ladder, and with the help of civilians began battering it against the gate like a ram, trying desperately to break it down. Finally, after five or six blows, the lock gave way. Once inside the courtway the firemen lifted their thirty-six-foot ladder and heaved it against the front window of Room 211, an eighth-grade classroom in the north wing. They placed the twenty-six-footer at Room 209 in the back corner of the U. Children began climbing down from Room 209, but those in Room 211 were having difficulty getting onto their ladder.

Kamin next split his crew. Two of his men, aided by civilians, took the company’s fifty-foot ladder into the alley north of the school. Romanczak and fireman Jess Martens followed with their seldom-used life net.

Seconds later Squad 6 pulled up, and its five firefighters, under the command of Lieutenant Jack McCone, joined the laddermen in the courtway. The firemen were stepping over bodies, unfolding a second life net, trying to get in position next to the wall. No sooner did they open the device and lift it waist high than the first eighth-grader came hurtling down from the back window of Room 211. The boy was large, and he landed on his back. The firemen dumped him out, quickly raising the net back into position, ready for the next child. Another student came flying down into the net. The men repeated the process, dumping him out and standing back up.

Then came another child. And another. And another. Soon the youngsters were plummeting into the net three and four at a time. It was only seconds before the number of kids dropping from the windows became too much for the net to handle. “Hold on!” shouted the firemen. But the kids could wait no longer. The classroom was too hot. Their shirts and sweaters were starting to burn. The firemen had no time to clear the net for other children to land. It wasn’t going to work. In desperation the rescuers dropped the net at their feet and starting reaching out with open arms, trying to catch the leaping students or otherwise break their falls before they hit the concrete.

The youngsters were jumping one right after the other. Some of them were caught by adults and firemen crowding the courtway. Others landed flat on the concrete, their falls uninhibited. Lieutenant McCone of Squad 6 tried catching one youngster, but the large boy fell through his outstretched arms, cracking his skull on the pavement.

The pace of rescue now quickened. Firemen were climbing ladders and grabbing children off the sills, bringing them down one at a time or dropping them to the ground. They were moving injured students out of the way, dragging them to the sidewalk to keep them from being hit by other falling children. Some youngsters jumped out as firemen were coming up the ladders to grab them. The kids were pretty heavy—eighty-five to a hundred pounds. The wooden ladders bounced under the strain.

Kamin turned and noticed that an elderly man had started up the ladder leading to Room 211. The man was standing on a lower rung, waving his arms, pleading for the children to come down. But the kids were stuck, unable to reach the ladder on their own. They had jammed themselves so tightly in the window space that those up front were literally pinned against the ledge, unable to move.

“Look out,” Kamin yelled. He grabbed the old man by the legs and pulled him off before climbing to the window himself.

Thirty-six and built like an ox, Charlie Kamin had been a fireman for nine years. Most of his career had been spent on ladder companies, whose members usually possessed the upper-body strength needed for forcing entry into buildings, pulling ceilings, and carrying bodies over their shoulders. Kamin fit the mold of a truck man well. He was large, strong, and imposing, standing six feet, two inches and weighing 220 pounds. The muscles in his arms and back were hard, and he had grown accustomed to the sights and sounds of peril.

But nothing in his worst nightmares could have prepared him for the scene he was about to encounter at the top of the ladder. When he reached the window he came face to face with the most terrifying sight in his life. Bunched before him in the smoke was a pile of eighth-graders stacked in more layers than he could count. Dozens of hysterical kids were crowding the opening, all screaming and pulling at each other in a mad fit to reach safety. Burning debris was falling from the ceiling, and those nearest the ledge were fighting to grab hold of the ladder. They were gasping on smoke, trying desperately to breathe fresh air. “Hold on!” Kamin shouted. “Don’t jump!”

Kamin could feel the heat inside the classroom. It was unbelievable. The animal was hot. It was on the loose. The heat was pressing against Kamin’s face, burning the skin on his forehead beneath the brim of his leather fire helmet. Experience told him the room was ready to light up, that he was dealing in seconds. The children crowding the open window space were yelling, yet he could hardly hear them. All he could think was “Get them out! Get them out!” He shoved a few kids back, away from the sill, so he could reach in and start plucking the tangled children one at a time.

Michelle Barale was one of those reaching for help. The fourteen-year-old was fighting her way to the window after being blocked by the throng of classmates who stormed in front of her. Only moments before she had been sitting at her desk in fear. She heard herself scream when the round light fixtures above exploded from the intense heat. The shattered white glass rained down upon the children. Michelle had thrown her arms over her head to shield herself from the flying glass, then jumped up from her seat, determined to escape. Moving toward the window, she could hear Sister Mary Helaine shouting something to her—Michelle couldn’t make it out. The normally austere nun had lost control of her charges. She looked pathetic as hot embers fell from the ceiling, burning holes in the big, square hood she wore on her head.

Michelle was growing furious as her path to the window was blocked by the growing pile of bodies on the floor and the tangled mess of classmates before her. A boy next to her was putting his hands around another girl’s neck, pulling her out of the way. Michelle looked down to the floor and spotted one of her girlfriends, Frances Guzaldo, lying on her side. Michelle kicked the girl, trying to rouse her. “C’mon, Fran! We have to get out!”

When Frances failed to respond, Michelle moved on, stepping over her friend and the other bodies that lay in the way, ducking burning chunks of lathe and plaster falling from the ceiling. The room was growing darker and she was now a few feet shy of the window. Her path was blocked by a couple of students stacked on the floor beneath her. A fireman appeared at the window. He was reaching in, pushing and shoving students out of the way. Michelle climbed over her downed classmates, then, using their bodies as a springboard, launched herself forward, reaching and crawling over the shoulder of other students blocking her way.

Standing atop the ladder, Kamin could see the girl coming at him. With one hand on the ladder, he reached in and grasped Michelle around the waist, pulling her out through the narrow opening. He swung her around the right side of his body until he felt her feet settle on the rungs of the ladder. He knew he didn’t have time to take her all the way down. He leaned over, setting her feet first on the ladder, leaving her to climb down by herself.

Kamin turned back to the window and, from that point on, worked like a robot, reaching inside the room and grabbing students—all boys because he could pluck them by their belts. He was lifting them up, pulling them out, swinging them around his back, and dropping them on the ladder behind him, hoping they would catch hold of the rungs. If they grabbed the ladder, fine. If not, he had to let go. He didn’t have time to worry about the ones he dropped. If they were to live he had to get them out. A broken bone was better than death.

The room was growing hotter and hotter and Kamin knew instinctively that time was running out. Smoke was pouring in through an open door, following a path straight to the windows. It was rolling into the room with so much force that, for a second, he thought it might blow him off the ladder. It was getting blacker and blacker, obscuring his vision, filling his lungs, making him hack and cough.

The children were screaming, but still he could hardly hear them. The heat was getting worse and the kids were changing color. Each time he turned to grab another child, Kamin could see their shirts turning from white to tan, darker and darker. He had been at the ladder for about a minute and a half and could sense that his time was just about up. When he looked in again he saw a flame. The room had finally reached its flash point. The air was igniting.

And then it blew. It just burst. One thunderous “poof.” The blast caught Kamin square in the face, searing off his eyebrows, burning his ears. He ducked his head and reached in one last time, managing to grab hold of a boy whose clothes were on fire, pulling him out.

He then saw the rest of the children in the window just wilt and turn dead, like a bunch of burning papers. It was the oddest thing. They didn’t tumble or fall over. Instead their knees simply buckled, dropping them straight to the floor like a house of cards.

Kamin limped down the ladder carrying the boy, one arm supporting himself, the other wrapped around the child’s waist. Flames from the youth’s burning clothes were shooting up inside Kamin’s worn black fire coat, scorching the skin on his right hand and forearm. “Goddammit,” he cursed. The pain was incredible, shooting up his arm like a bolt. It was the hardest thing not to let go. But he held on for a few more seconds, long enough to feel his left boot hit the bottom rung. When he reached the concrete he handed the eighth-grader off to another fireman, who began slapping out the flames with his mitt. He slung the boy over his shoulder and ran for an ambulance.

Kamin dropped his helmet and leaned against the building. He bent over, placing his hands on his knees. He was rubbing his arm, catching his breath, trying to contemplate the deadly scene he had just witnessed. Only a few short minutes had elapsed since Truck 35 pulled up to the school. Yet for Kamin it seemed like hours. He glanced around the courtway, trying to catch up with the unfolding disaster.

What he saw inside the narrow U resembled a war zone. Injured and dying children were lying everywhere. Those still conscious were moaning in pain. Police and neighbors were running into the areaway, scooping the kids up, carrying them away. Kamin looked back up at the window. A boy’s body was hanging off the sill, his arms dangling. He was dead. One of the squadmen rushed up with a pike pole. He reached up with the tool and tried to pull the boy out, but the body slipped back inside the room. Another fireman in the courtway bent over and started vomiting. Even for the professionals, the sight was too much.

FIREMAN FIRST-CLASS Salvatore Imburgia was behind the wheel of Hook and Ladder 36, steering the long apparatus around a backup of mid-afternoon traffic, past the stores and shops lining Chicago Avenue. The truck men were due on the box alarm and were moving pretty well, knowing they were in for rescue work.

Imburgia was feeling tense and had a sense of foreboding. A small bull of a man who took pride in his physical strength, he wasn’t worried about himself, for he was fearless at fires. Rather he was concerned about his two young sons. Both boys attended catechism classes on Wednesdays at Our Lady of the Angels School. Imburgia was having trouble recalling what day it was. He was racking his brain, trying to remember.

“What’s today? Monday or Wednesday? It’s Monday. Okay.”

That mystery solved, he still felt uneasy. He lived in the neighborhood; Our Lady of the Angels was his parish. He’d been married there, attended Sunday Mass there. Most of his buddies’ kids attended school there. His fears started mounting when the frantic voice of Henry Holden came crackling over the radio: “Engine 85 to Main! Give us a two-eleven and send all available ambulances. We’ve got a school on fire. Kids are trapped on the second floor. They’re jumping from windows!”

Imburgia felt his stomach tighten as he floored the accelerator.

FIRE COMMISSIONER QUINN also heard the urgency in Holden’s voice as the engineer called for the second alarm—a request usually reserved for battalion chiefs and above. The telegraph was going crazy, spewing out tape, ringing incessantly. Nine more fire companies, including the snorkel, were now en route to the school.

Quinn grabbed his hat and overcoat and hurried out his office door.

“Let’s go!” he shouted to his driver.

It was 2:47 p.m.

Five minutes had now elapsed since the Fire Department first learned of the fire.

CHIEF MILES DEVINE of the 18th Battalion pulled up in his sedan at Our Lady of the Angels within three minutes of the first alarm. The 18th took in a big chunk of the West Side, and no matter what type of emergency he was called to, the fifty-eight-year-old Devine had learned how to keep his composure intact. The firemen in his battalion trusted his judgment. But after taking one look at the burning school, the normally cool Irishman started coming apart.

The scene greeting him was one of bedlam. Firemen were climbing ladders, plucking students from windows, slinging them over their shoulders or simply dropping them to the ground. Police, firemen, and civilians were standing beneath windows, catching students in life nets or with outstretched arms. They were picking up the injured off the pavement, carrying them to police cars and private autos or into neighboring homes.

The chief grabbed his radio. “Battalion 18 to Main! Send me eight more ambulances and tell the police to start squadrols! We’ve got lots of injured here! Some are DOA!”

Seeing the enormity of the situation, Chief Devine went right to work, deploying his box-alarm companies. Hook and Ladders 26 and 36 were ordered into the alley to start laddering windows there. Track 35’s aerial ladder was raised to the roof of the north wing, and more truck men were sent up to swing axes and chop holes in the roof to vent the deadly heat and smoke mushrooming through the cockloft and second floor. Incoming engine companies were directed to lay hose lines for an interior attack on the flames.

In an attempt to make the main second-floor corridor usable for rescue, Engine 95, the second pumper to reach the scene, led out with two hose lines up the front stairway in the north wing. Working without air masks (they didn’t have them in 1958), the firefighters dragged their hose lines through the hot, blinding smoke, crawling up the stairs on their hands and knees, inching their way toward the flames. Engine 44 stretched two more handlines up the rear fire escape while Engine 68 took another line into the south wing off Iowa Street.

To ensure that an ample supply of water was being delivered to the fireground, second-alarm engine companies were ordered to drop additional supply lines through neighborhood alleys and side streets. Lines were laid up and down Iowa and Avers. Firemen were dragging hose lines over curbs and sidewalks, through the swelling crowd of frantic parents assembling outside the school.

By now the fire had been burning for more than a half-hour, eating its way through most of the second floor in the north wing. But the flames had not yet burned through the roof. They couldn’t. Through the years as many as five hot-tar roof coverings had been poured over the building, creating an impermeable seal that now prevented the fire from burning through on its own. Consequently flames, heat, and smoke were being held inside the classrooms and cockloft, sandwiching the victims inside. Had the old tar been stripped after each new application, the fire could easily have burned through the roof and vented itself, making conditions inside the building much more tenable. Instead the results were disastrous.

Suddenly and without warning, as firefighters were inching their hose lines up the front stairs, a resounding crack resonated through the neighborhood. A large portion of the roof near the burning back stairway had been weakening for some time. Finally it collapsed, sending the roof and second-floor ceiling crashing down into the burning classrooms. The rush of smoke and superheated air accompanying the collapse sent a shock wave throughout the structure, snuffing out the last traces of life from most of those still trapped inside. The blast knocked firemen down two flights of stairs. Rescuers atop ladders were chased to the ground.

WHEN THE CONCUSSION from the collapsing roof blew through the upper windows, it seared the eyelashes right off firefighter Salvator Imburgia’s face.

The fireman was teetering atop a ladder, reaching through a window of Room 208, trying to pull out a seventh-grader when debris from the falling roof came crashing down before him. The tiny space where the boy’s feet were wedged between the inside wall and a radiator was now filling with burning timbers and ceiling plaster. In an instant the blond-haired youth disappeared in a massive cloud of smoke and dust. All that remained were pieces of his flesh that had rubbed off his body onto Imburgia’s gloves.

Imburgia was knocked off balance. When he regained his footing and looked back inside the room, it was like a twilight zone. The children were lit up, burning like human sparklers. Everything inside the room was blazing.

Imburgia couldn’t believe what he was seeing. He had boxed his way through the navy and had seen combat in the South Pacific, but he had never dreamed of anything this awful. He knew the room was filled with children, how many he couldn’t estimate. At that point no one knew. He had managed to rescue six youngsters, pulling them through the window and tossing them to the ground. But when he reached in for the last badly burned boy, he couldn’t free him. Imburgia called on every ounce of his strength, reaching in with both arms, vainly trying to yank the lad free. The child was now buried under heavy debris. Imburgia ducked his head and tried one last time to reach back over the sill, to try and feel his way to the floor, hoping to grab hold of the boy’s arm. But he couldn’t find it.

Below in the alley, Imburgia’s captain was yelling for him to retreat. “For chrissakes!” the officer shouted, “get down here. Don’t be stupid!”

CHIEF DEVINE keyed his walkie-talkie. “Battalion 18 to Main!” he shouted. “We’ve got a roof collapse. Occupants are trapped. Gimme a five-eleven!”

The chief was jumping straight to a fifth-alarm—the most serious—skipping the normal routine of first calling for a 3-11 and 4-11. He knew he was breaking protocol, but he didn’t care. The situation called for it.

In the main fire alarm office, however, the operators weren’t so sure. “Battalion 18,” one of them replied, “say again?”

The chief barked back: “I said five-eleven! And don’t knock it down. Gimme a five-eleven for Box Five-One-Eight-Two!”

“Okay Battalion 18, we’ll give you a five-eleven.”

In firehouses and newsrooms across the city, fire tickers started pinging out the “five-bagger.” The alert crackled over the fire radio to notify companies that were out of quarters: “A five-eleven alarm fire, 3808 West Iowa Street, on the orders of Battalion 18.”

A huge cloud of thick black smoke was now rising into the afternoon sky. It could be seen for miles, like a homing beacon for the army of emergency vehicles headed for the school. Sixty fire companies, including ten ambulances, were now on the scene or responding. Seventy stretcher-bearing police squadrols also were en route.

It was 2:57 p.m.

Fifteen minutes had passed since Nora Maloney called the Fire Department.