REMORSE

ON TUESDAY, December 2, 1958, Chicago awoke in grief. Banner headlines brought home the news to a shocked city, and under Mayor Daley’s orders, flags on all public buildings were lowered to half-staff.

The fire’s toll was appalling. Eighty-seven children and three of their nuns were dead; ninety other students and three more nuns were injured, some with fractured skulls, broken bones, smoke-damaged lungs, and terrible burns. It was the worst fire to hit Chicago in fifty-five years. Not since the Iroquois Theater fire of 1903, in which 602 were killed, had so many lost their lives in a single blaze.

Throughout the city’s stricken West Side, a nightmare was continuing for many families. Funeral directors received weeping parents and prepared for scores of wakes and funerals. But with the grief, questions began to arise: How did the fire start? How did it spread so quickly? Why did it go unnoticed for so long? And why did so many die? As investigators sifted the ruins and pieced together conflicting reports, disturbing facts began to emerge.

Our Lady of the Angels School, like many schools of its day, had no sprinkler system or smoke detectors, and its fire alarm rang only inside the building; it did not transmit a signal to the Fire Department. The school’s second-floor staircases were open, without fire doors, and the building had just one fire escape. Window ledges were thirty-seven and a half inches off the floor—too high, it was determined, for many of the younger children to climb over. Consequently quite a few of the dead were found stacked beneath the windowsills. Finally, with an enrollment of approximately fourteen hundred students in the main building, the school was considered to be overcrowded.

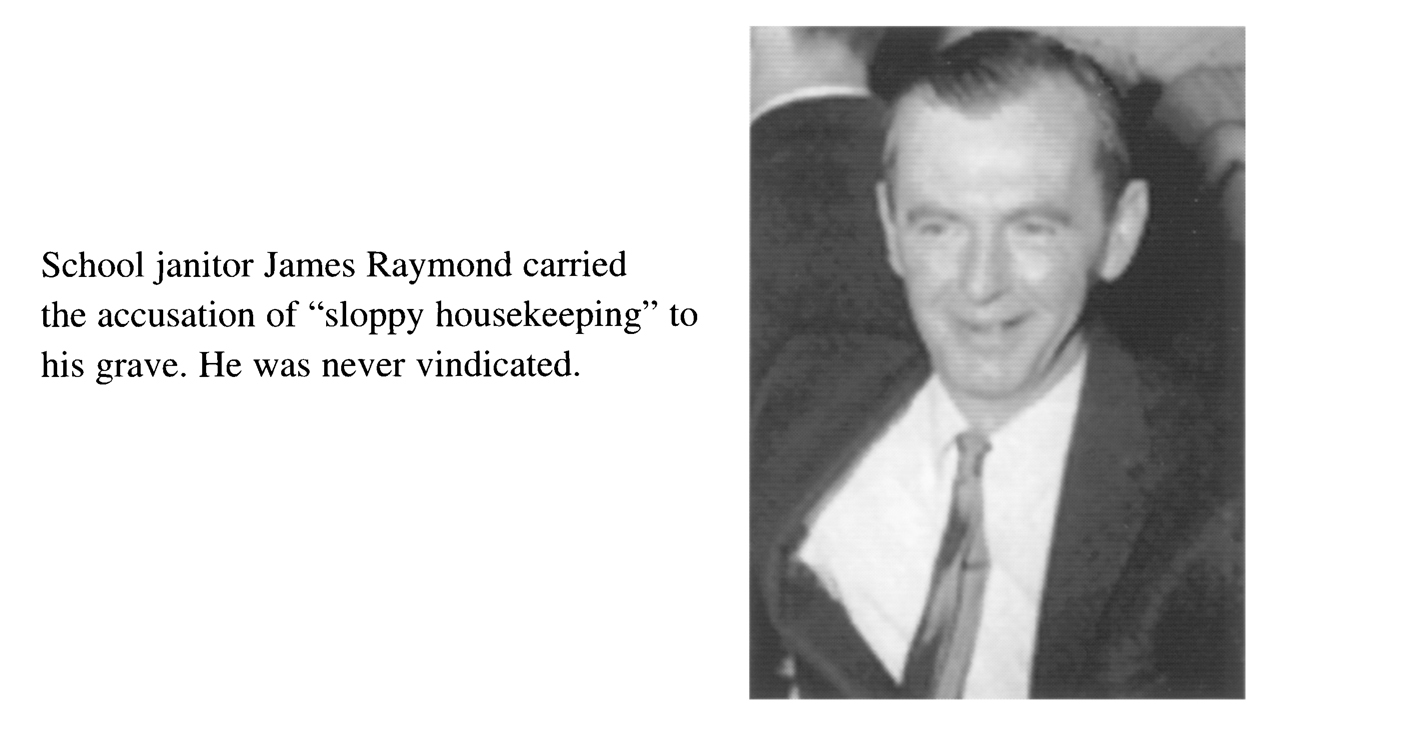

Just a day after the disaster, some officials, notably Captain Henry Penzin, commander of the Austin Police District, blamed the fire’s rapid advance on “sloppy housekeeping” after police bomb and arson detectives discovered a five-gallon can of paint thinner in the basement boiler room. The charges of negligence gained support when investigators found piles of clothing, old newspapers, exam papers, cardboard boxes, boxes of paper, and other debris in the basement. The clothing, it was later learned, had been collected during the parish’s annual clothing drive, which had begun the week before.

Still, the school had passed its most recent fire inspection in October. Although Chicago’s 1949 municipal code required that all schools built after its passage be constructed of noncombustible materials and equipped with fire-protection devices such as sprinkler systems, fire doors, and fully enclosed stairways, structures already in existence were governed by a 1905 ordinance that mandated none of those modern safety requirements.

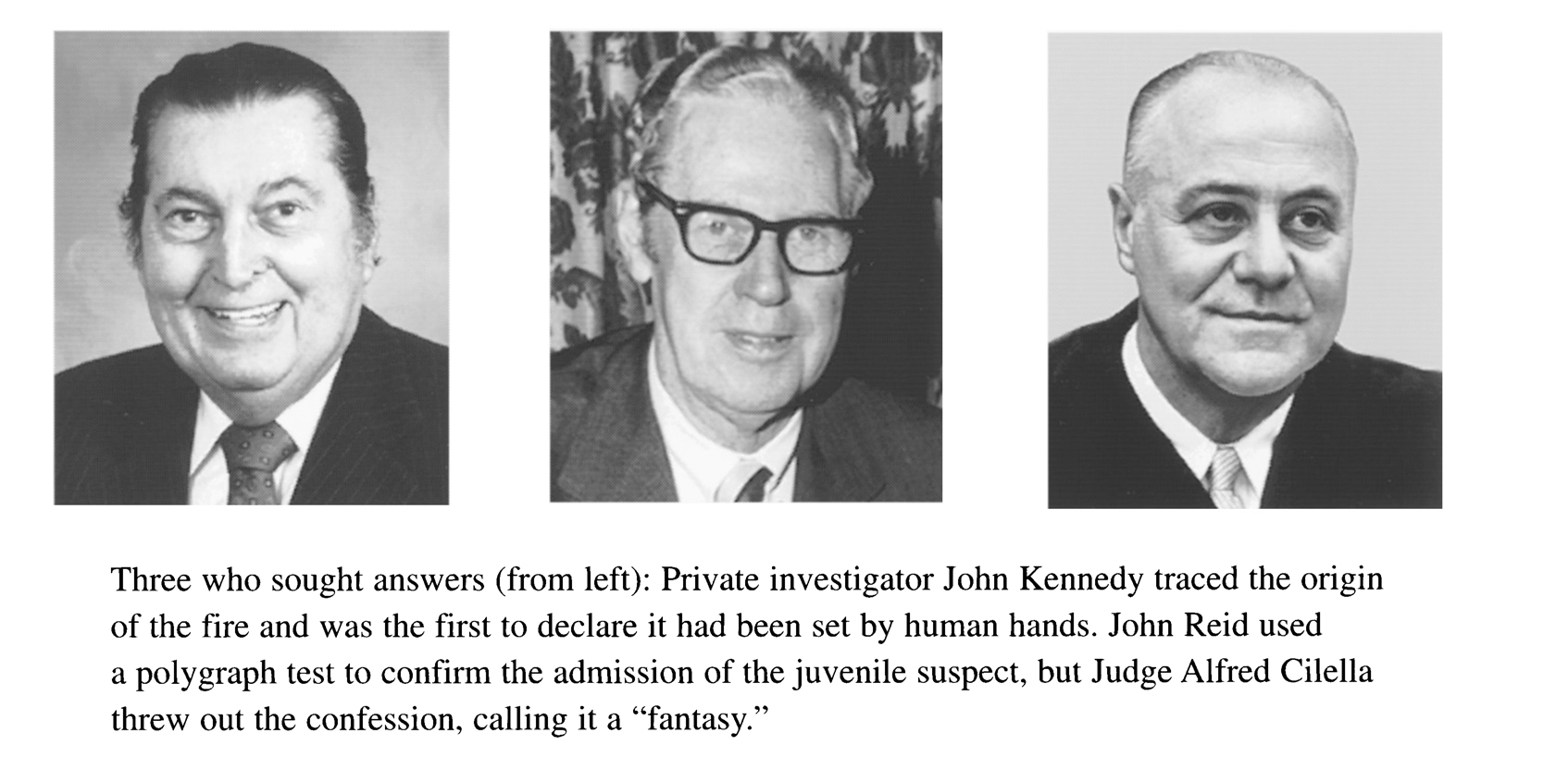

After the fire was extinguished, pumps were brought in to siphon water from the basement of the school, and within the next forty-eight hours—after debris had been screened and carefully examined—evidence remained to pinpoint the exact spot where the fire had started.

At the bottom of the isolated, seldom-used northeast stairwell, on the checkered, asphalt-tile floor, investigators found a grey metal rim buried beneath a layer of ash and sediment. The rim still encompassed a few inches of charred fiber edging from the base of a trash container to which it had been attached. When the floor was scrubbed down, a circular mark defined where the container had stood. Portions of the nine-inch square tiles directly beneath the barrel were virtually unmarred.

A section of baseboard molding one foot away from the container showed signs that the fire had burned there for a long time. The molding had been thinned out by severe charring. It was a telltale discovery. The deeply charred V-mark in the molding pointed to the base of the fire, where flames had been most intense at its start.

Because of the chimney effect of the fire coming up from the basement and the burn patterns on the walls, investigators were sure this was the point of origin. Next they turned to the more grievous question of the fire’s cause.

Initially it was thought the boilers in the coal-burning furnace may have exploded, but a check showed that the heating system had been working properly. Faulty electrical wiring was also ruled out as a possible cause. And no evidence suggested that the fire was fed by an accelerant.

Investigators were checking out stories of furtive student smoking in the basement, but so far no solid evidence pointed to a discarded cigarette as a possible cause. The only other possibility for investigators to consider was that the fire had been set—either accidentally or intentionally—by an unknown person.

Although they lacked this crucial piece of the puzzle, officials reconstructed the fire’s rapid progression. Sometime after 2 p.m. the blaze started in the ringed, thirty-gallon cardboard trash drum located at the bottom of the northeast stairwell. After consuming refuse in the container, the fire smoldered undetected, elevating temperatures in the confined, L-shaped stairwell space, where the lower parts of three walls were covered with heat-reflecting sheet metal.

When intense heat shattered a window at the bottom of the stairwell, a fresh supply of oxygen was sucked into the area, causing the smoldering fire in the waste drum to flash up. Flames quickly spread to the unprotected wooden and asphalt-tiled staircase, feeding off the varnished woodwork and walls covered with fourteen layers of paint—the top two layers composed of an extremely flammable rubberized-plastic paint that produced heavy black smoke.

Because the building was without a sprinkler system, the stairwell quickly turned into a chimney. Flames, smoke, and gases billowed up the stairway from the basement. A closed fire door on the first floor stopped the blaze from entering the first-floor corridor, and it continued unchecked up the stairway and swept into the eighty-five-foot-long corridor leading to the second-floor classrooms. Inside the corridor, the flames fed on combustible wooden flooring, walls, and trim, as well as the ceiling, filling the corridor with deadly columns of penetrating black smoke. Within a few minutes the small fire had grown into a raging inferno, exceeding temperatures of fourteen hundred degrees Fahrenheit.

While the fire made its way up the stairwell, hot air and gases in the basement had entered an open shaft from a disconnected drinking fountain in the basement wall and flowed two stories upward inside the wall. This hot air fanned out into the narrow cockloft above the second-floor ceiling, sparking serious secondary burning in this hidden area directly above the six north-wing classrooms packed with 329 students and six teachers. Those flames eventually dropped into the second-floor corridor from two ventilator grilles in the ceiling, further trapping the occupants from escaping into the hallway.

Some survivors reported that after classroom doors had been opened and quickly closed, they heard a loud whoosh, thought to have come from an explosion that accompanied the ignition of volatile fire gases that had built up in the corridor. When intense heat from the fire began breaking the large glass transoms over classroom doors, smoke and flames entered the rooms, spread across flammable ceiling tile, and forced the occupants to the windows.

This was the situation inside the north wing when the first fire company, Engine 85, pulled up at 2:44 p.m. As firefighters concentrated on rescue, the blaze on the upper story of the north wing grew steadily worse and eventually burned off one-third of the roof before being brought under control. Desperate as the situation was, in the decisive early moments of their arrival firefighters still managed to save 160 children, pulling them out of windows, passing them down ladders, catching them in life nets, or otherwise breaking their falls before they hit the ground.

One crucial and confusing circumstance for investigators was that the fire had burned undetected for so long—at least twenty minutes. The north side of the school had been heating like an oven, with fire spreading inside the stairwell, walls, and cockloft, yet no one realized the building was ablaze until it was too late.

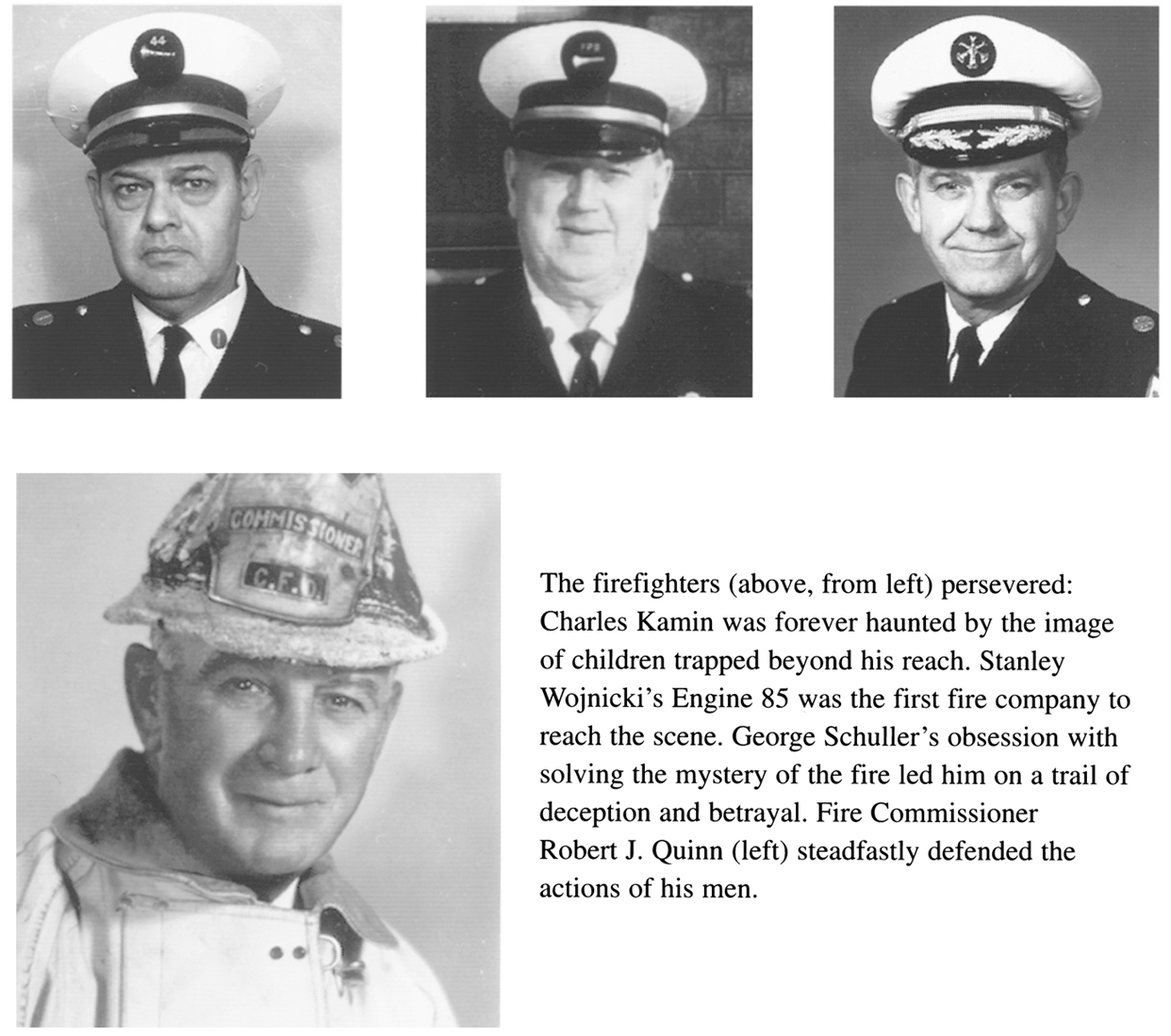

FOR FIRE COMMISSIONER QUINN, the night had been long and exhausting. In all his years as a firefighter he had never encountered anything so terrible, and he was feeling uneasy. Already rumors were circulating that the Fire Department was guilty of slow response, that ladders were too short to reach the school’s high, second-floor windows. It was not true, and Quinn knew he would have to set the record straight. If there was a delayed response, it surely wasn’t the Fire Department’s fault. If firefighters had been called sooner, the kids could have been saved.

Still, this was all theory, and before he met with the army of reporters bivouacked inside the City Hall press room, Quinn needed facts. Because he had not arrived at the school until after three o’clock, he ordered all firefighters on the still-alarm companies to report to his office first thing Tuesday morning to give depositions describing their actions upon pulling up to the scene.

For Quinn, the Fire Department was his life. He took pride in knowing that Chicago had one of the finest firefighting forces in the world, and he worked hard at keeping the department on the cutting edge of the profession. True, firefighters had saved 160 children at the school under hazardous conditions, yet in light of 90 deaths the number of rescues was little comfort. The fact that such an enormous tragedy could occur in Chicago and under his command was a hard pill to swallow.

As the weary, grim-faced firemen began trickling into his office shortly before nine o’clock, their minds still haunted by the sights and sounds of the day before, Quinn received them with little more than a grunt. He was visibly upset, his face as cold as stone. The men knew they were in for a grilling.

Being in charge of the first fire companies to reach the school, Lieutenants Stanley Wojnicki and Charles Kamin were shown in first. On hand inside the office were Quinn’s top deputies, including Chief Fire Marshal Raymond Daley, in charge of the uniformed force, who had also been at the school.

Once all were in place, Quinn, sitting behind his desk, set down his glasses and rubbed his bloodshot eyes. “There’s going to be a million reporters in here,” he said gravely. “I don’t want any bullshit. I want answers. That’s why you’re down here.”

Kamin was asked to speak first. The thirty-six-year-old veteran related how he had immediately ordered his men to tear down the iron fence and begin rescue operations inside the courtway and on the alley side of the building. He also described the tense scene he had encountered while working atop the ladder at Room 211. “I reached in and pulled them out,” he said. “I didn’t have time to worry about the ones I dropped. Then it flashed. It was over real quick.”

When Kamin finished, Wojnicki began his deposition. The lieutenant of Engine 85 was exhausted, still numbed by the agony and death he had witnessed the day before. Like most of the others he had been up all night and had not slept a wink. All night long he kept asking himself the same question: Did I do enough? Did I do enough?

Wojnicki was an unsophisticated but sensitive man, and his emotions were torn. He kept turning over in his mind the awful dilemma he had faced upon pulling up to the school. He knew if he had tried to save a few of those kids himself—raised a ladder and went up and started yanking pupils off the windowsills—and then waited for another engine company to come in and start water, he would have been hanged. His job was to get water on the fire as fast as possible. That’s what he did.

Struggling to keep his composure, Wojnicki described how, after being directed to the correct location of the fire and positioning the engine on Avers Avenue, he stretched a hose line into the alley and began attacking the flames in the rear stairwell.

“You saw fire in the stairwell?” Quinn asked.

“Yes,” Wojnicki answered. “It was roaring. It was going straight up. I figured it had to be the seat of the fire.”

Quinn: “Did you try to get any of these kids out?”

“Not at that time. We were too busy with the line.”

Quinn: “What do you mean you were ‘too busy with the line’? You’re saying you pull up and you’ve got kids hanging out of the goddam windows, and you didn’t try to get kids out? You dumb sonovabitch! What the hell’s the matter with you?”

Wojnicki was stunned. He had always respected Quinn, but at the same time the commissioner intimidated him. Still, he held his ground. “I knew I had the truck coming in behind me,” he said. “We tried making those stairs, to get up inside there. There was just too much fire for us to get in.”

Another deputy spoke up. “Lieutenant,” he said, “you say you attacked the fire in the stairwell, that the flames were going up the stairs. Do you suppose you assisted in pushing the flames up the stairwell by directing your hose line in there?”

“No,” Wojnicki answered. Suddenly he was feeling nervous. Where were they going with this line of questions? In appeal, he looked over to Chief Daley, a bulldog but a respected member of the department. “I think we saved a lot of kids by knocking down that fire in the stairway,” Wojnicki pleaded. “I know we did. I don’t know what else I could have done.”

Daley could see that Quinn was upset. They were all upset. They weren’t in the habit of losing ninety people in a school fire. As he listened to the facts, Daley concluded that Wojnicki had fulfilled his responsibilities as officer of the first engine company on the scene. He came to the lieutenant’s defense. “Considering the circumstances,” he said, “I don’t know how the hell you did what you did do.”

Daley gazed over to Quinn, trying to diffuse the tension. “That was his job,” he said. “He did his job. For chrissakes, those people were grabbin’ at him. What more do you want?”

Quinn, still angry, relented a bit. “All right,” he said, rubbing his eyes. “Is there anything more?”

“After the fire was knocked down a little,” Wojnicki continued, “we were ordered to put our line in the snorkel, then help remove bodies. We picked up about ten o’clock.”

After listening to the lieutenants’ stories, Chief Devine of the 18th Battalion gave his own account, explaining in his Irish brogue how he had deployed the first-arriving still- and box-alarm companies, then telling how he radioed for the 5-11 alarm when the roof went in. “We tried,” he said, “God how we tried. But we couldn’t move fast enough. No one could live in that fire. I saw four of them leaning over a windowsill, crying. We tried to reach them. Then suddenly they slumped, doubled over the sill. They were dead when we got to them.”

After the remaining interviews were completed, Quinn walked over to meet Mayor Daley for a City Hall press conference. As he headed for the mayor’s office, he felt for his men. They tried. They did their best. As fire commissioner, what more could he ask?

When the press conference started, Quinn described for reporters what actions the department had taken at the school, promising that additional facts would be forthcoming during the coroner’s inquest scheduled to begin the following week. Still, Quinn wasted no time in blaming the high loss of life on the delayed alarm to the Fire Department. “That school was as safe as any in Chicago,” he declared. “It had a fire escape and six exits. But the kids on the second floor couldn’t reach them because of the smoke.”

Nor, he noted, could they reach the school’s fire-alarm pull stations, which resembled light switches and were located six feet off the floor.

The adequacy of exits at the school also was at issue. Exit adequacy—as determined by proper enclosure, provision of at least two ways out remote from each other, and sufficient exit capacity for all occupants to leave the building promptly—was an established principle in building construction and fire safety long before Our Lady of the Angels. Yet the school did not meet these safety standards. When asked by reporters why he thought the building had sufficient exits after almost one hundred children didn’t get out, Quinn responded that the number of exits was “all that was required under the law.”

Despite Fire Department records showing that Our Lady of the Angels School could be evacuated in three and a half minutes, the commissioner pointed out that the trouble began after students tried to enter the hallways but were forced back into their classrooms by intense heat and smoke.

“The layman doesn’t seem to understand that once a fire gets going, it goes faster than you can run,” he said. “All you need is one inhalation of superheated air and your lungs collapse and your life is snuffed out. If we had been called three minutes earlier, we could’ve gotten all those kids out.”

Quinn did admit, however, that part of the blame could be placed on the city’s 1949 municipal code, which contained no “grandfather clause” requiring the installation of sprinkler systems and fire doors in existing buildings such as Our Lady of the Angels School. He said he planned to push for a city ordinance mandating sprinkler systems and fire alarm boxes for all public buildings.

When Quinn finished, a grim Mayor Daley announced that he had ordered “full and complete reports” on the fire, and vowed to station a fireman in each of the city’s public and private schools that were found to be lacking in fire protection. “A tragedy of this magnitude should not go without hope that we can somehow improve the protection of our children,” the mayor said.

THAT SAME MORNING John Raymond awoke in Franklin Boulevard Hospital with a badly bruised hip and an injured back that made it hard for him to move. Severe smoke inhalation made it feel as if he had swallowed a jar of tacks. But he was lucky, for unlike other, more critically burned and injured students, his hospital stay would be relatively short: one week.

Lying in bed with an intravenous line in his arm, John still didn’t know what had happened, just that he was in a bad situation. He remembered stumbling inside his aunt’s house across the street from the school, falling down on a couch, then being picked up by a stranger who carried him to his car and drove him and a few other children to the hospital.

John was hungry—don’t they feed you in these places? He had never been in a hospital, at least not since he was born. His mom hadn’t come by. She was still busy with his dad in another hospital. One of his uncles had told John that his dad had been injured but was okay.

A newspaper deliveryman walked inside the room. “Here,” he said to John, “have a paper. You can pay me tomorrow.”

When John unfolded the paper, the bold, black headline leaped off the front page: NINETY DIE IN SCHOOL FIRE.

Ninety! How did it happen? Immediately John thought of his two brothers. He was still unaware that they had escaped unharmed. He riffled through the pages, scanning the death lists. Their names were not there. Thank God for that. They must be okay.

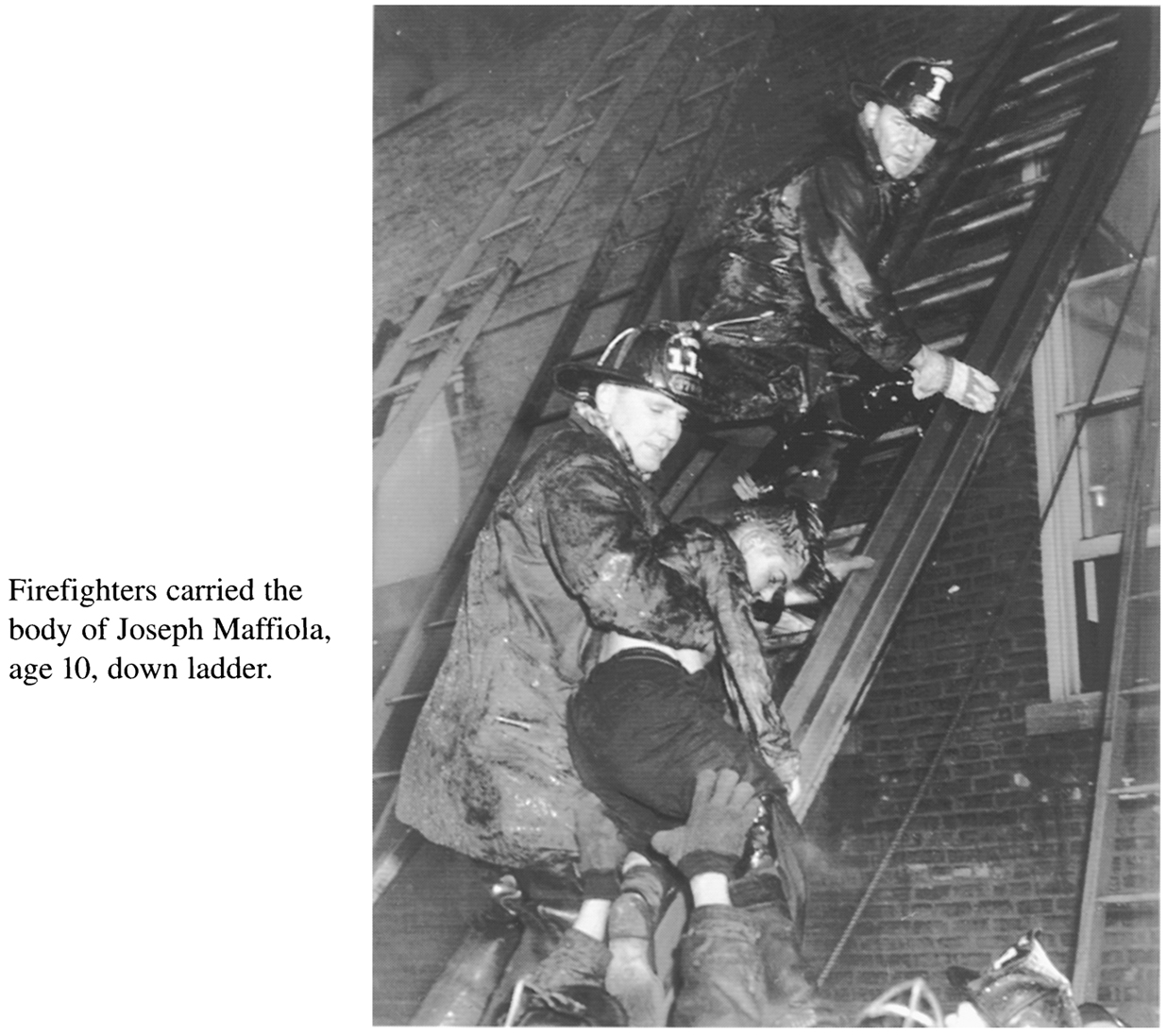

Other familiar names, though, filled the long columns: Wayne Wisz. Margaret Sansonetti. Annette LaMantia. Larry Dunn. John Mele. Joseph Maffiola. Karen Baroni. Joseph King. They were all kids from John’s room. He saw another name: Frank Piscopo was his next-door neighbor. They were buddies, classmates, hung around together, walked to school together every morning.

John couldn’t believe what he was reading. It was like a bad dream. He counted the names. Twenty-seven of his classmates were dead. He went further down the list. He saw his nun’s name, Sister Mary Clare Therese. She was dead too.

John had never known anyone who died, and now it seemed like everyone he knew was dead. Yet he was alive. God heard his prayer. He had been saved. But why him and not them?

TO THE SOUTH, in Garfield Park Hospital, John’s father was in turmoil.

Jim Raymond was still in shock from blood loss and too upset to answer lengthy questions. He had become physically sick and vomited when police tried taking an initial statement from the janitor as he lay in his hospital bed on the night of the fire. In the confusion outside the school, the elder Raymond had scuffled with several firemen who tried to subdue him and walk him to an ambulance when he tried to reenter the burning building to save more children. Finally, when all else failed, one fireman hit him over the head with a pike pole, knocking him unconscious. He was then rushed to the hospital, where he received stitches to close the gash on his head and the injured wrist he had cut after smashing out the window on the second floor.

Lying in his hospital bed, Raymond replayed the awful scene in his head. He thought about the smoke. He would never lose the taste of that smoke. It was peculiar. Thick. Dense. Hot. He could breathe coal smoke and wood smoke. But he couldn’t breathe the smoke from the fire. When his thoughts shifted to the children who died, he began to weep uncontrollably, burying his face in his hands. He felt so responsible. If only he’d gotten there sooner, he could have gotten them out. As a parent he knew he was lucky. His kids had escaped. Johnny was hurt, but at least he was alive.

And how did the fire start? He must have asked himself the question a thousand times. The boilers were fine. He had checked them just an hour before the fire. Everything was fine. Maybe a kid was smoking down there. He’d seen cigarette butts in the basement in the past, but not recently. Besides, he always chased kids out of the basement when he caught them down there. He hadn’t seen any that day. If one of the kids did start the fire, it had to have been accidental.

When a newspaper reporter asked the janitor what may have sparked the blaze, Raymond replied, “It had to be human hands. That’s all I can say.”

SITTING ALONE in the living room of his small home on 97th Street, Richard Scheidt was still mulling over what he had seen at the school fire. The Tuesday afternoon papers had just hit the streets, and Scheidt was feeling self-conscious. He looked at the large photo on the front page of the Chicago American showing him, his face in anguish, carrying the begrimed, limp body of a ten-year-old boy from the school. The stirring image had captured the essence of the tragedy and would appear in newspapers and magazines throughout the world.

Although Scheidt was identified, the boy in the photograph was not named. The caption asked readers for help. “Do you know who this boy is?” When the boy’s aunt saw it, she phoned the paper, asking to speak with an editor. “That’s my nephew,” she said.

The youngster was given a name. He was John Jajkowski, a fifth-grader from Room 212. He sang in the boys’ choir. He had been looking forward to Christmas. He wanted to be a priest.

Scheidt set down the paper. He was saddened. He had pulled nineteen children from the wreckage, all of them dead. He was still shaken.

Later that evening Scheldt’s telephone rang. It was John Jajkowski’s father who wished to meet with Scheidt, “just to talk.” Scheidt was reluctant. He remembered the advice of his older brothers when he had first joined the Fire Department eight years earlier: “Don’t get too involved. It’s only a job.”

Since then Scheidt had grown into a hardened firefighter himself, and he had seen his share of tragedy. He had worked the Barton Hotel fire on Skid Row, where twenty-nine men had died. And the blaze at the Reliance Hotel, where five firemen had been killed. And countless automobile accidents in which he had removed mangled bodies, and the “everyday fires” that snuffed out lives just as quickly.

Through the years he had learned to let go, to purge himself of the daily pathos that was part of his job. But this school fire was different. He would never forget it. It involved kids, and so many of them. It shook him. He was a father himself. Three of his four children attended parochial schools. It could have been him on the other side of the line.

Scheidt decided to make an exception. “Okay,” he said softly, “I’ll meet you. That would be fine. Whenever you like.”

The next night Scheidt drove to the Jajkowski home on North Lawndale Avenue, three blocks from the school. John Jajkowski opened the door. The two fathers shook hands and sat together in the kitchen over cups of hot coffee. Other family members were present. Jajkowski’s twenty-nine-year-old wife, Josephine, was under sedation in another room. The couple’s remaining child, two-year-old Steven, lay asleep in a crib.

“Was he already dead when you found him?” Mr. Jajkowski asked.

“Yes,” Scheidt answered.

When he returned home later that night, Scheidt looked in on his kids—three boys and a girl. They were sound asleep. He wondered what they would become when they grew up.

Scheidt was due to work at the firehouse the next morning. He woke up at six, wanting to call in sick. Instead he got dressed and drove to the firehouse.

DURING THE WEEK crowds of curious onlookers continued to flock past the closed school to see the ravaged building that had been a death trap. Police had barricaded the streets from automobile traffic, and pedestrians were barred from entering.

In the December sunlight the scene remained eerily quiet. But beneath the somber appearance, nerves were fraying. Some parents and relatives, angered by the helpless frustration of losing a loved one, lashed out at those responsible for the safety of their children.

“They only had one damn fire escape in the whole place.”

“Why wasn’t there a fire door on the second floor?”

“Why didn’t they pull the fire alarm sooner?”

“Who was in charge?”

As the finger-pointing multiplied, parish priests began receiving death threats over the phone and in person, as did school janitor Jim Raymond. Police provided round-the-clock protection for them. Still, on the streets of the stricken neighborhood, kindness and sensitivity were the rule. One woman whose children had grown and moved away, walked up to a nun outside the parish convent and pressed some folded currency into her hand.

Community centers and Red Cross stations across Chicago were crowded with people who showed up to donate blood, some going as far as to offer parts of their skin to help treat the children’s burns. At Cook County Jail, inmates lined up to donate blood, and at Stateville Prison in Joliet, inmates sacrificed cigarette and candy rations, donating what money they had to assist the families of the dead and injured. Labor unions and other organizations also contributed money, and soon donations began arriving from around the world to Mayor Daley’s Our Lady of the Angels Fire Fund. By week’s end more than $100,000 had been collected to assist families with medical and funeral expenses.

Newsmen were allowed inside the fire-wrecked school where, amid the ruins and reminders, they took photographs and cursed under their breaths. In some rooms textbooks sat open on charred desktops, and shoes left behind in the mad rush to safety lay in puddles on the floor. On the first floor the coatracks were still full. But little remained untouched on the second floor. Here most of the garments, like many of their young owners, had been destroyed by fire.

Meanwhile, as a task force of forty investigators—including fifteen juvenile officers—was sent on a sweeping inquiry into the cause of the fire, investigators probing the ashes remained stymied as to its cause. No evidence was found to suggest spontaneous combustion, and no specific ignition source was located. Samples from the school’s charred walls and stairs, and remains from the thirty-gallon waste drum found in the basement, were taken to the police crime laboratory for inspection and analysis. Some officials still clung to the theory that a cigarette tossed by a student sneaking a smoke in the stairwell, or by workers making deliveries through the basement door, may have touched off the blaze. And, as much as they tried to discount the possibility, investigators were seriously beginning to consider arson as a probable cause.

County Coroner McCarron announced plans to hold a special coroner’s inquest the following week. McCarron had named a sixteen-member “blue-ribbon” jury whose task would be to determine cause of death and investigate the fire’s origin. Meanwhile, Fire Commissioner Quinn revealed that officials intended to question five hundred upper-grade students at Our Lady of the Angels School. Quinn said survivors would be asked:

What children were out of their classrooms in the period immediately preceding the fire?

Which children were assigned to dump waste paper in the basement on the day of the fire?

Which students smoked cigarettes?

Mimeographed consent forms were prepared in order to obtain permission from parents to allow their children to be questioned.

City Fire Attorney Earle Downs met with bomb and arson detectives to begin the arduous task of checking pupils against a master file containing the names of three thousand known juvenile firesetters in the city. But by week’s end the check had produced no tangible leads.

Police had hit a dead end. They still had no answers.

ON WEDNESDAY, December 3, positive identification was made on the last four bodies that remained at the county morgue. The bodies, all girls, had been burned beyond recognition.

One girl was dressed in the blackened remnants of a blue school uniform with a safety pin at the waist. A second, larger girl, wore a metal ring with a pink stone, and had red nail polish painted on her fingers and toes. A third body had on underclothing embroidered with a red clock and the word “Sunday.” The fourth body had a prominent overbite, but other than that revealed nothing more than gender.

Positive identification was made possible only through family dental records. The four were identified as Lucile Filipponio, age eight; Diane Marie Santangelo, age nine; Bernice Cichocki, age twelve; and Rose Ann LaPlaca, age thirteen.

Initially the parents of two of the girls refused to acknowledge that the bodies were those of their daughters. They later accepted the assurance of dentists and physicians who said the teeth in the scorched bodies matched those on the victims’ dental charts. The mother of the girl with the nail polish had never seen her use it, so the parents of this child also hesitated before finally claiming the body as their daughter.

In a twisted sequel to the tragedy, police were hunting for a man who telephoned the relatives of two of the dead girls, demanding a cash ransom for the safe return of each child. While the girls’ parents agonized at the morgue over whether to believe the bodies belonged to their daughters, the caller told the aunt of one of the girls that her niece was still alive. “If you want her, bring $25,000 to 5520 West Diversey Avenue,” the caller said. Police detectives sent to stake out the location discovered the Northwest Side address to be a vacant lot. They searched the area but came up with nothing.

The bodies of the three nuns killed in the fire were returned to the convent across the street from the burned-out school. Along with a basket of white carnations, three simple, brown coffins, each closed and adorned with a silver crucifix and nameplate, were placed on the sidewalk outside the convent, where prayers were offered by Bishop Raymond Hillinger. As Hillinger recited the Rosary, heartbroken nuns dressed in black and white joined hands in the December cold and prayed for the souls of their beloved sisters. When the service ended, the coffins were moved inside to a small chapel. More than two thousand mourners filed past the three coffins, waiting in a line that stretched half a block. Included among the mourners were parents whose children had died alongside the women.

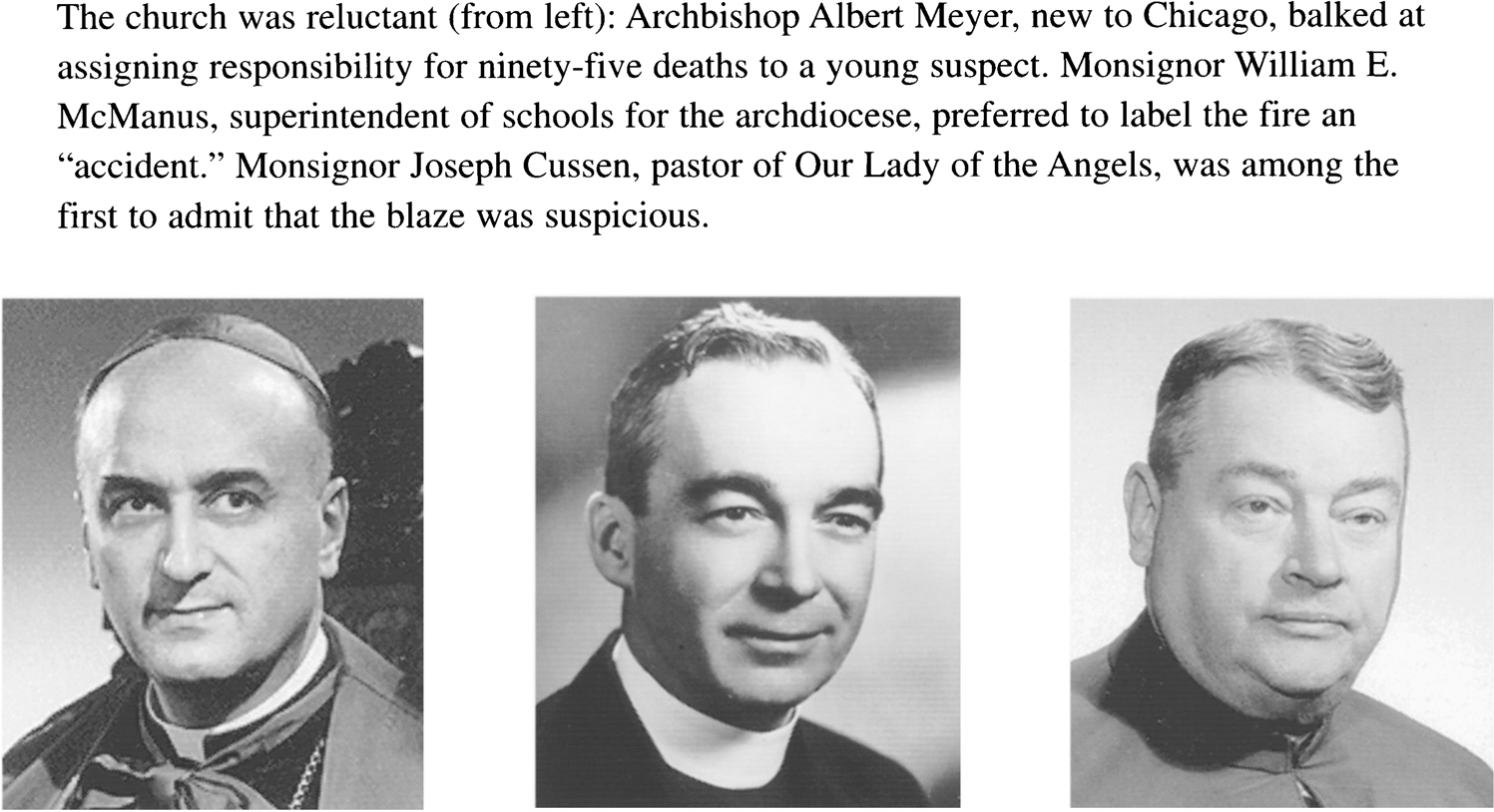

On Thursday the three coffins were carried across the street into the parish church for a solemn funeral Mass and eulogy delivered by Archbishop Meyer and Monsignor McManus, superintendent of schools. The coffins were carried by eighteen parishioners—six for each—followed by a color guard of one hundred police and firemen.

Thinking about what he would say, McManus concluded that the three sisters had given much of themselves to their students. In their tragic, untimely deaths, it seemed only fitting that they had stayed behind, dying alongside the children. When the fire broke out, the nuns didn’t think to save themselves. They didn’t run. They didn’t panic. They didn’t leave the children behind. They stayed with them, all the way through the fire to the ultimate journey from earth to heaven.

McManus decided not to question their judgment in trying to get the children out or having them stay put inside the rooms. Nobody could make that judgment unless they were actually inside those rooms and knew exactly what the conditions were like. The nuns may have opened the doors and saw the inferno in the hallway and figured there was no way out. Or maybe they were wrong in not trying to run for the stairs. McManus concluded it didn’t matter. What had been done had been done. Now, as a community, they must cling to their faith, to accept God’s will and go forward.

Approximately one thousand mourners packed the church that morning to hear McManus celebrate the funeral Mass. More than a hundred grieving nuns filled the pews in the first three rows. Because there was not enough room inside the church to accommodate everyone, many more mourners stood outside on the front steps and sidewalks. Loudspeakers were set up so that those standing in the cold, raw wind could share in the words of comfort.

In concluding his eulogy, McManus said, “Our three sisters died magnificent deaths…. There is no mother who could have been more unselfish, nor more heroic, than our three sisters who died with their children.”

When the service ended, the coffins were carried outside and loaded into hearses, then driven to Mount Carmel Cemetery in suburban Hillside, a few miles west of Chicago. There the three were lowered into their final place of rest, in a special plot reserved for the Sisters of Charity.

BY WEEK’S END, fourteen of the ninety-three school fire injured remained in critical condition with severe burns and fractured bones.

At St. Anne’s Hospital three critically injured children were clinging to life. One of them, Victor Jacobellis, lay in a coma, his prognosis poor. The nine-year-old fourth-grader had broken his neck and crushed his chest after jumping off one of the high windowsills in Room 210. The neurological damage had left him in a vegetative state. He was being kept alive by a respirator.

Nick and Emma Jacobellis had remained at their son’s bedside since the night of the fire. As the week progressed, Victor’s condition didn’t change. Finally, on Friday, doctors accompanied Nick and Emma to a quiet room at the end of the hall. “I’m afraid there’s nothing we can do,” they said. “It’s up to you, but we would recommend cessation of support. He’s not going to come out of it.”

Pragmatic Nick Jacobellis trusted the doctors’ judgment. If there was any hope, they would have found it. This was not the way Victor would have wanted it. For all practical purposes, his son was already dead. Still, it was not an easy decision. But they were strong people. What else could they do? It was God’s will. “Whatever you say,” Nick said.

That evening Nick and Emma Jacobellis visited their son for the last time. They wept as a doctor turned off the respirator that was keeping Victor alive. After a few minutes, Victor expired. The fire had claimed its ninety-first victim.

SISTER DAVIDIS remained in St. Anne’s for a week. After her release from the hospital she was met at the convent by members of the news media who had been waiting to ask her about the final minutes in Room 209.

As reporters and photographers began crowding into the convent’s first-floor reading lounge, word of the press conference reached Monsignor McManus, the archdiocesan school superintendent, who quickly became angry at the prospect of a nun facing an open interrogation and answering questions in a way that might prove embarrassing or damaging to the church. McManus and other officials were worried about the legal ramifications of the school fire; attorneys had already warned the chancery office about the possibility of lawsuits stemming from the fire. In the immediate aftermath, nuns and priests from Our Lady of the Angels parish were told to remain silent. No one was to answer any questions.

McManus wanted the interview stopped. He telephoned the convent and asked that the press conference be called off. “It’s too late,” a nun told him. “They’ve already begun.” McManus rushed to the convent from his office downtown, entering—as one nun later recalled—”like a black cloud.”

Meanwhile Sister Davidis, dressed in her black habit, conducted herself with grace and sincerity, speaking slowly and deliberately as she described for reporters the final moments leading up to the time she and her eighth-graders reached safety by jumping out windows or climbing down ladders and the drainpipe running along the outside wall.

“It happened in a matter of seconds,” she said, “but it seemed like thirty years.”

“Sister,” a reporter asked, “do you have any idea how the fire started?”

“I have no idea whatsoever,” the nun responded.

When another reporter suggested that a pile of waste paper stored under the back stairwell helped the fire’s rapid advance, Sister Davidis objected. “No,” she said. “Sister Florence kept the school immaculate. I know of no cases where waste paper was stored under the stairwell.”

After the question-and-answer session ended and the reporters started to disperse, Monsignor McManus admitted that after all it was probably a good idea for Sister Davidis to get her story out in the open. She had nothing to hide.

In the days following the fire, the BVM nuns traveled in groups to attend wakes for the many school fire victims. Bereaved parents appreciated their presence and personal concern. But as time passed the nuns sensed a gradual change in sentiment among people living in the neighborhood around the school.

“I can remember riding the bus to St. Anne’s Hospital to visit some of the children,” one nun later recalled. “When we got on, everybody in the bus stopped talking. By then, the BVM habit had become famous. They knew who we were, and you could feel the criticism in their silence, as though they were thinking, ‘Oh, so you’re the ones who didn’t get the kids out.’”

IN A TIME when American sensitivities had not yet been blunted by the assassinations of the Kennedys and Martin Luther King, Jr., and by the cruelties of the war in Vietnam being brought into the country’s living rooms on color television, the news of the Our Lady of the Angels fire jolted the nation and the world. Newspapers across the country filled their front pages with headlines and photographs of the fire, and American television networks led their nightly newscasts with reports from Chicago.

Across Europe, newspapers and radio stations reported the tragedy at great length. In London the BBC called the fire “too awful for words.” In the Soviet Union, though, the official Communist news agency Tass and Radio Moscow used the school fire to harangue the United States for spending too much money on military hardware and approving only “miserly allocations” toward school safety. The fire, they asserted, was “no accident.”

Meanwhile, messages of sympathy poured into the city from around the globe, including cables from German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and Pope John XXIII. Regarding the arson claims being advanced in some circles, the Vatican said: “It does not seem possible that anyone could take such action against innocent children. We refuse to believe this and are inclined to think it was an accident.”

The repercussions of the Chicago school fire were felt in every American city, large and small, as officials nationwide reviewed their school fire-inspection programs. Fire officials from several of the nation’s cities and from as far away as London dispatched representatives to Chicago to study the blaze and gather information to help prevent a similar tragedy from striking their communities.

In New York City, Fire Commissioner Edward J. Cavanagh ordered the immediate inspection of that city’s fifteen hundred public and private school buildings. Fire inspectors were ordered to pay particular attention to basements, exits, waste disposal systems, housekeeping, and fire drill efficiency. “We conduct these regularly and we are certain our schools are safe and in fine condition, but we are taking this step as a matter of assurance to parents and others concerned,” Cavanagh explained.

In 1957, 127 minor fires had been reported in New York City schools. In 1958 the number sat at 117. John J. Theobald, New York City’s school superintendent, said he did not believe such a tragedy could occur in his city because, with the exception of four older wooden schools in Queens, all of New York’s schools were “fireproof.”

Yet within the first twelve hours inspectors in New York closed four schools and evacuated more than a thousand pupils. One was a Hebrew school in Brooklyn where fire officials found hallways and fire exits blocked with lumber, desks, and other obstructions. Windows were found to be fixed with iron bars. A second Hebrew school in Manhattan was found to be strung with ancient open wiring. Two public schools in the Bronx had sprinkler systems out of service, and in one of these, acetylene torches and oxygen tanks were found stored in the building’s basement. By week’s end, eighteen New York schools had been closed for safety violations.

Despite Chicago’s public school officials labeling their fire-prevention program as the most “extensive efforts in a generation,” Fire Commissioner Quinn ordered fifty lieutenants from the Fire Prevention Bureau to begin inspecting every public and parochial school in the city. Inspectors’ biggest concern was a lack of panic hardware on school doors. And because of conditions found at Our Lady of the Angels School, inspectors also chose to target accumulations of rubbish, obstructed exits, and barred doors. Still, Quinn told reporters that no schools would be closed, and he cautioned parents there was “no need to become frantic.”

“All Chicago schools are in good condition, but we just are not taking any chances,” Quinn said. “If we find one that is in bad condition, we will station one or two firemen in there during school hours. This will apply to all school buildings.”

But fire-protection problems were institutional as well as local; because of Chicago’s current building code, scores of older schools and other public buildings in the city were without sprinkler systems and other fire safety devices. Everyone knew it would take more than one or two firemen stationed on the premises to impede the spread of any fire.

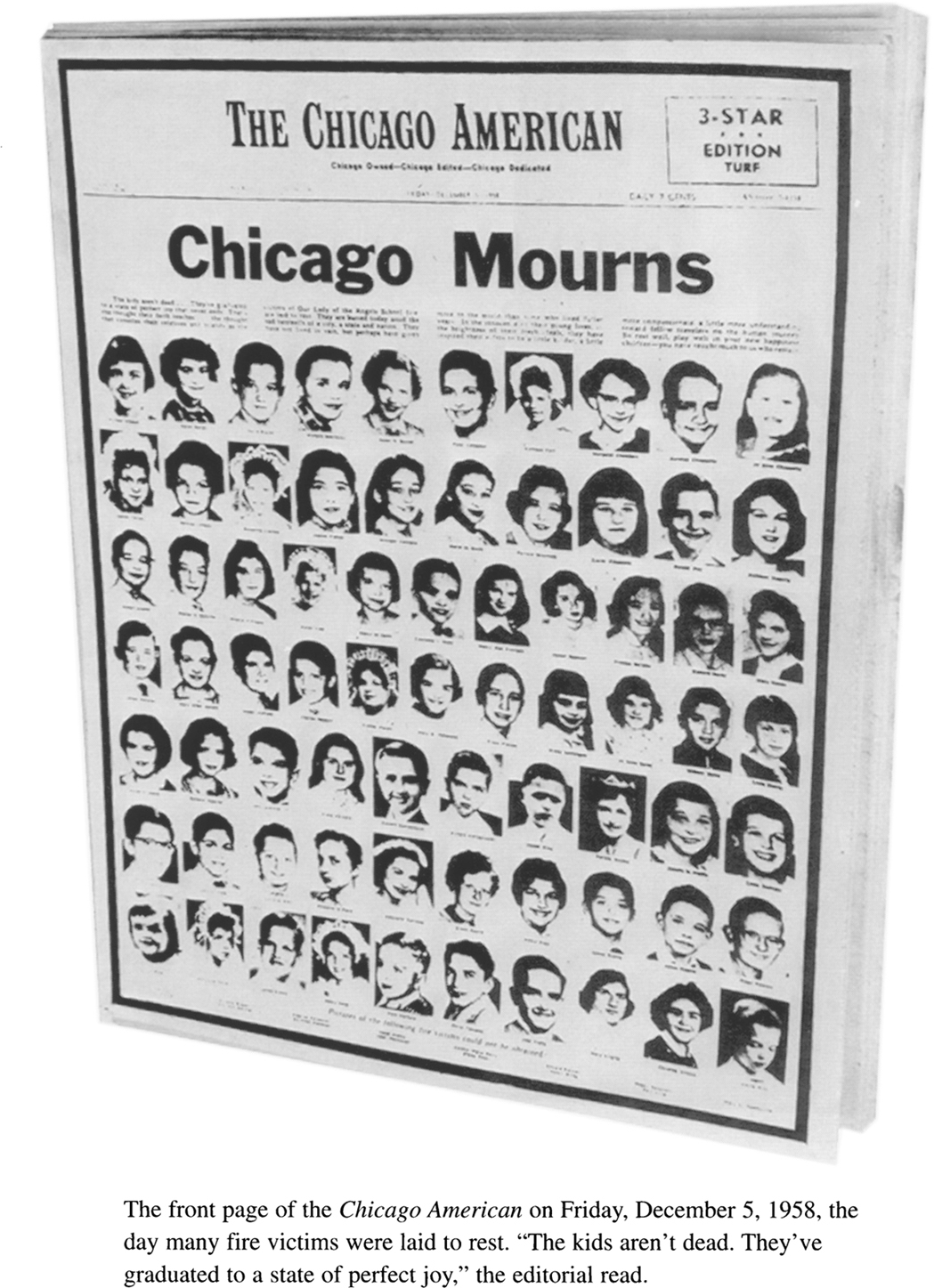

ON THE FRIDAY after the fire, a solemn requiem Mass was offered for twenty-seven of the dead children—eighteen girls and nine boys—in the Illinois National Guard Northwest Armory on North Kedzie Avenue. Wakes and funerals for the remaining sixty-one children killed were being held privately elsewhere throughout the city’s West Side and in nearby suburbs. Some parents chose private services rather than play out their grief in public. They had endured enough, deciding to sequester their loss among themselves. Still, in deciding to hold the mass funeral, archdiocesan officials had deemed the rites as a tribute for all who had perished in the school fire.

Seven thousand persons attended the 10 a.m. rites at the huge grey armory abutting Humboldt Park, many arriving more than two hours early. Wheeled inside were twenty-seven coffins in white and gold, each pathetically small but different in size, provoking its own set of memories. Above the coffins, on the armory stage, was a portable altar surmounted by six candles and a crucifix. Archbishop Meyer, his face gray and contorted in sorrow, offered the Mass. Next to him, wearing a look of frozen grief, was Monsignor Cussen. Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York was also present.

In summing up the week of sorrow, Bishop Raymond Hillinger spoke to the congregation, referring to the slogan with which Chicago had recovered from the fire of 1871: “Today, this week, the motto ‘I will’ has meant ‘I will be kind.’ Chicago to us will always mean the city of the Good Samaritan.

“It would be folly to try to minimize the tragedy of last Monday afternoon,” Hillinger preached. “The fire was ghastly. It was hideous. It was horrendous. But God is not mocked. He does not allow disasters to take place without reason. The heavenly Father in His providence governs all things. The blunt but consoling statement is that He will draw untold good from the purgatory of this week. From the ashes, love, phoenix-like, has risen….”

During the Mass the choir sang Perosi’s “Libera Me,” usually sung at the rites of popes and cardinals. A chant of the Latin poem “Dies Irae,” based on a prophecy that the world will be destroyed by fire, was also delivered.

After the final prayers, heartbroken parents and relatives were asked to rise from their seats in the front rows and wait for their child’s name to be called: “Peter Cangelosi. David Biscan. Millicent Corsiglia. Christine Vitacco. Joseph Modica. Diane Marie Santangelo. Margaret Chambers. Joseph King. Aurelius Chiappetta….”

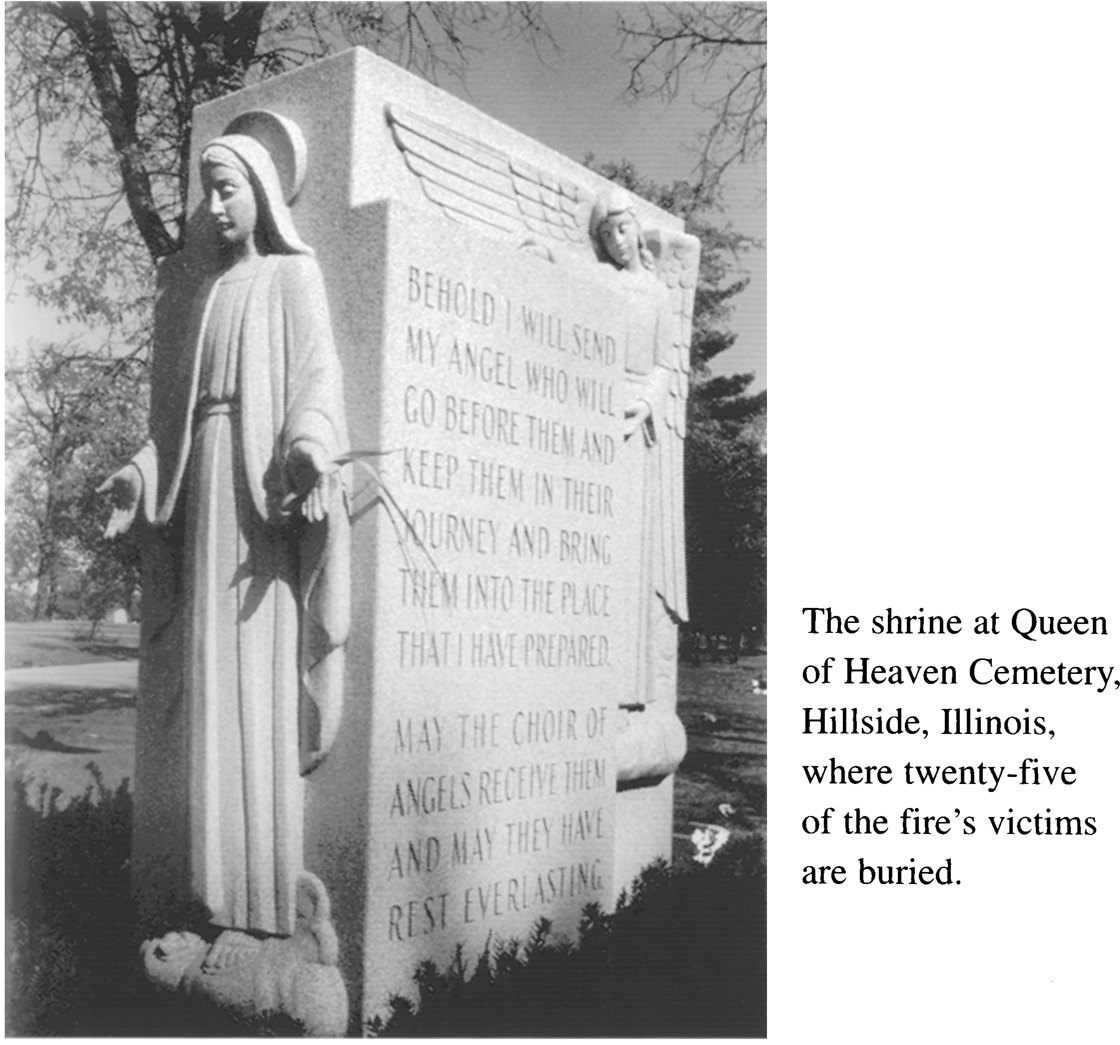

The families—some silent, others weeping or fighting back tears—fell in line behind the coffins containing their loved ones as they were wheeled outside to waiting hearses before an honor guard of policemen and firemen. The funeral procession then moved across the West Side and into the nearby suburbs, to Queen of Heaven Cemetery in Hillside, where interment services were held in the raw, icy cold.

At the burial site, veteran news photographer Jimmy Kilcoyne was shaken by what he saw: “The mothers were throwing their bodies on caskets and sobbing like they never wanted to let go.”

A memorial for all ninety-five victims of the school fire would eventually be erected on the burial site, a triangular plot known as the Shrine of the Holy Innocents, a section of the cemetery reserved for children.

ON THE SUNDAY after the fire, “The Angelus,” a small weekly bulletin distributed to parishioners at all the Masses at Our Lady of the Angels Church, contained no mention of the fire. Within the thick, black border on the front page, there was a simple message in large type:

“Blessed Are They Who Mourn

For They Shall Be Comforted …”

BEFORE MONTH’S END, two more students—both fourth-graders from Room 210—died, bringing the death toll to ninety-three.

Kurt Schutt, the ninety-second victim, died December 8 in Edgewater Hospital. He had been transferred there from Franklin Boulevard Hospital to permit the use of an artificial kidney machine—the only one in the city at that time—to filter impurities from his blood. He had been burned over 80 percent of his body.

“Kurt was very brave,” said a hospital worker who cared for him on the day of the fire. “I wanted to take off his glasses, which were blackened by smoke, but he put his burned hands up to hold them on. I let him keep them on.”

Susan Smaldone, the ninety-third victim, died December 22 in St. Anne’s Hospital. She suffered burns over 85 percent of her body, “but she was always in good spirits,” recalled a member of the hospital staff. As the days passed, a massive infection took over her swollen body, and her vital fluids diminished rapidly.

Susan had a beautiful singing voice. She had come out of the fire still believing there was a Santa Claus. Before she died, she had written him a note reminding him to look for her in the hospital.

The holiday season, usually a time of happiness and anticipation, was a time of mourning and sadness in Our Lady of the Angels parish. Darkness, it seemed, was everywhere.