Figure 13-8: Moving the light around (via wireless flash) can help you add drama to even the most boring subject. In this case I wrapped some paper around the flash; yielding a “tube” of light that was then placed below left. I’m telling you, wireless flash is worth the effort! TIP: The 60 flash has a feature where you can control the flash exposure compensation from the back of the flash as well as through the camera’s MENU -->  3--> Flash Comp. menu. If you should adjust both, the total of the two settings gets implemented, although the back of the flash and the camera’s menu will only show you their respective individual values. 3--> Flash Comp. menu. If you should adjust both, the total of the two settings gets implemented, although the back of the flash and the camera’s menu will only show you their respective individual values. |

|

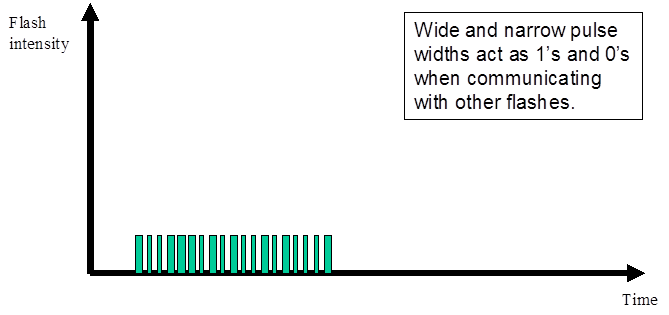

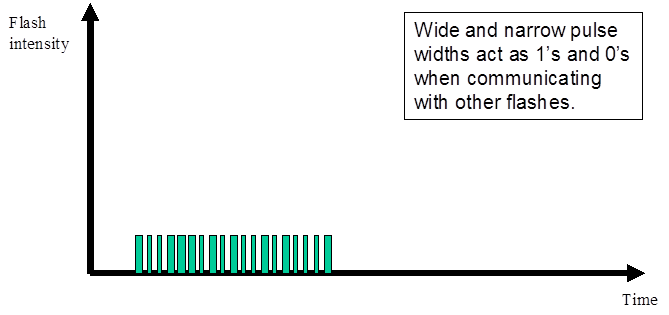

Back in 1991, Minolta engineers had developed the ability to have the camera and the remote flashes communicate with each other using tiny bursts of low-intensity light – kind of like a “Morse code” using long- and short-light pulses. (See Figure 13-9.) These pulses are too faint to significantly affect the final exposure, but are strong enough to communicate with any other flashes in the vicinity – even when they are reflected off the walls, ceiling, or the subject. This scheme allowed even the tiny pop-up flash of Minolta’s and Sony’s prior cameras to control several off-camera flashes at once without the need for cables. (This was a BIG DEAL if you've ever had to struggle with the cable method on a regular basis.) By sending long and short pulse widths of light at small intensities, the camera's flash could tell the other flash units how much light to output and when to start doing it.

Figure 13-9: The flashes can communicate with each other using a “Morse Code” of wide and narrow pulses. In the blink of an eye this protocol can individually address groups of flashes and tailor the output of each group. |

|

So, here's how the flash metering system works, from the moment you press the shutter release to the moment the camera finishes taking the picture:

1) The on-camera flash fires a "Morse code" that tells all flashes in the room to generate a short, fixed “pre-flash” of known brightness.

2) The pre-flash burst is reflected off of the subject and back to the camera. The camera’s sensor measures the intensity of the reflected pre-flash and compares it against any ambient light present.

3) The exact amount of flash brightness needed is calculated by the camera. The camera communicates the calculated brightness value to the off-camera flash via another Morse Code message.

4) The exposure begins.

5) The on-camera flash sends a Morse code command to all of the off-camera flashes telling them to “FIRE!” and output the previously-set flash burst.

6) All of the off-camera flashes fire with the proper intensity in a single burst.

7) The camera’s sensor may continue to collect light a little longer if you told the camera to use a longer exposure. Then the shutter closes and the exposure is finished.

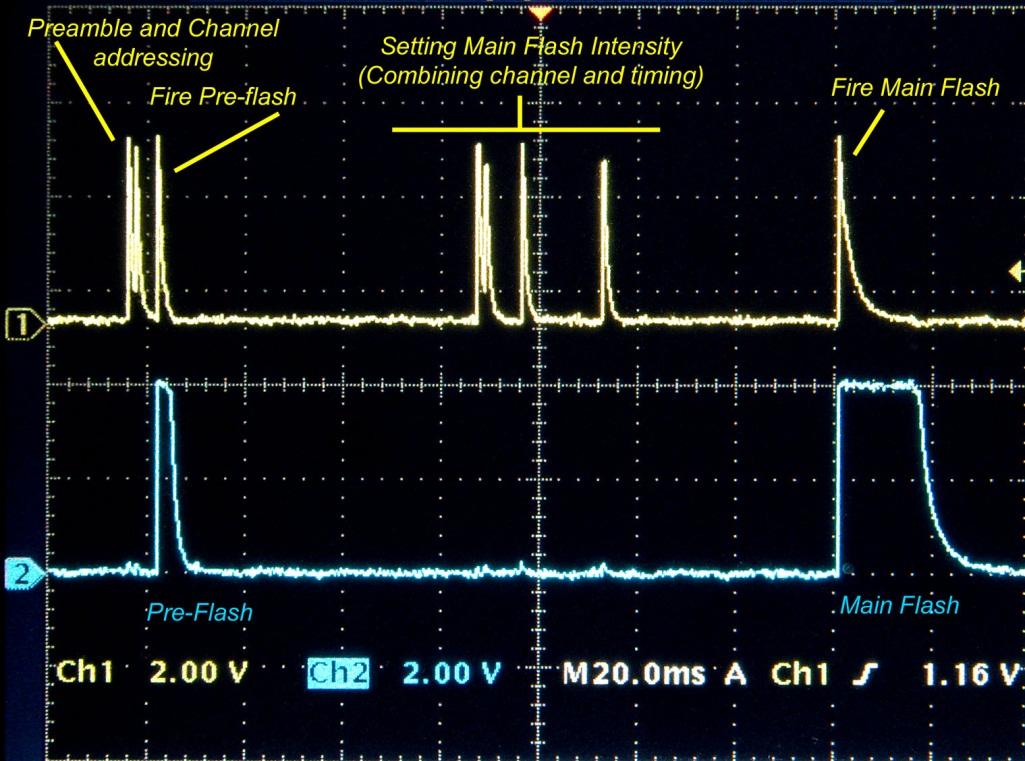

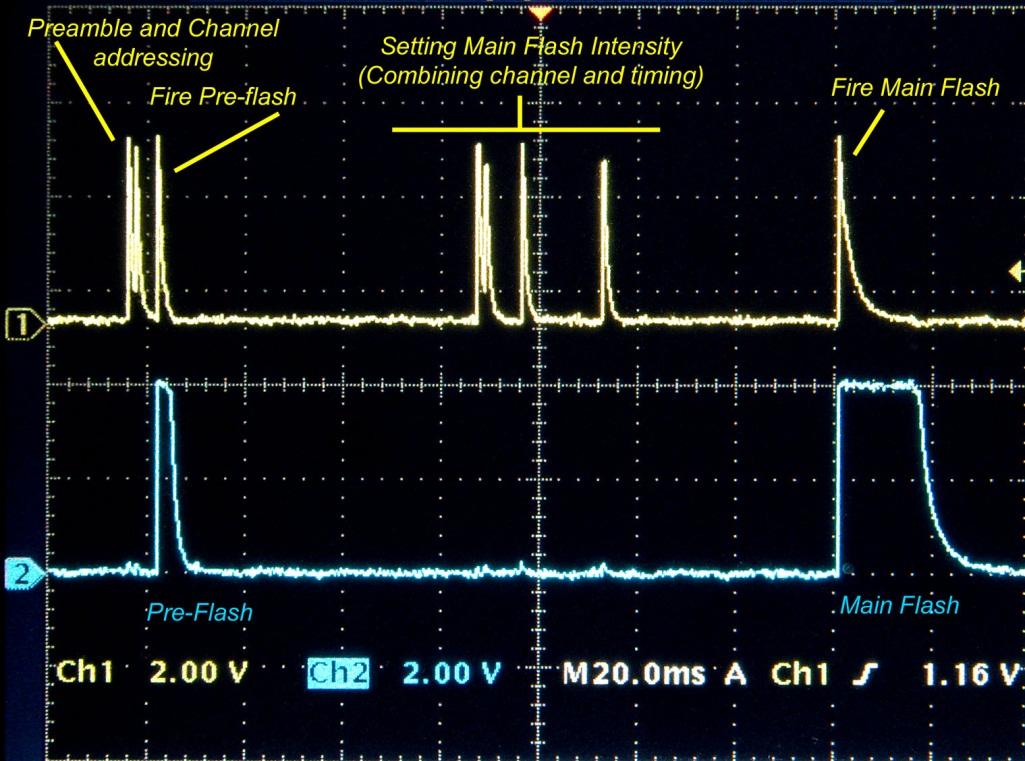

A real “conversation” between the camera and the remote flash has been recorded and appears in Figure 13-11. In this graph, time (in milliseconds) is represented by the horizontal axis, and each flash’s output is represented in yellow (the pop-up flash) and blue (the off-camera flash).

Figure 13-10: The sensor at the front of your slave flash (yellow square) must be able to see the control signals from the master. Line of sight is best; but it can also see control signals that bounce off of walls or the subject. |

|

Figure 13-11: This is what a conversation between the Master (top yellow) and the Slave (bottom, blue) looks like on an oscilloscope. The Master communicates to the Slave using combinations of wide and narrow flash pulses, and the Slave responds by firing a pre-flash and the actual flash of the proper intensity on command. The firing intensity is communicated to the off-camera flash in the middle section by a combination of pulses and time delay. This is the old wireless protocol in action – the new protocol is more complex than this and it takes a tad longer to execute. |

|

13.5 As Simple As It Gets

Okay, enough arm-waving. How do you actually get the camera and flash to work in wireless mode? Basically, it requires two flashes: One on top of the camera (I recommend the “F20M” flash for this purpose) and any other flash which acts as the off-camera “Slave” (either an F60 or F43). Slaves can be placed almost anywhere in the room as long as it can see the control signals coming from the Master, either via direct line-of-sight or after being bounced off a wall or ceiling (it’s pretty resilient). Just follow these steps:

Figure 13-12: Putting the camera into wireless flash mode |

|

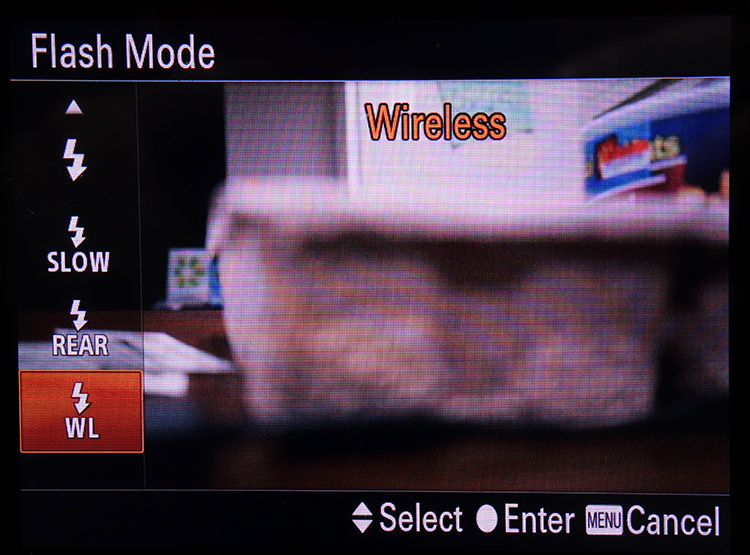

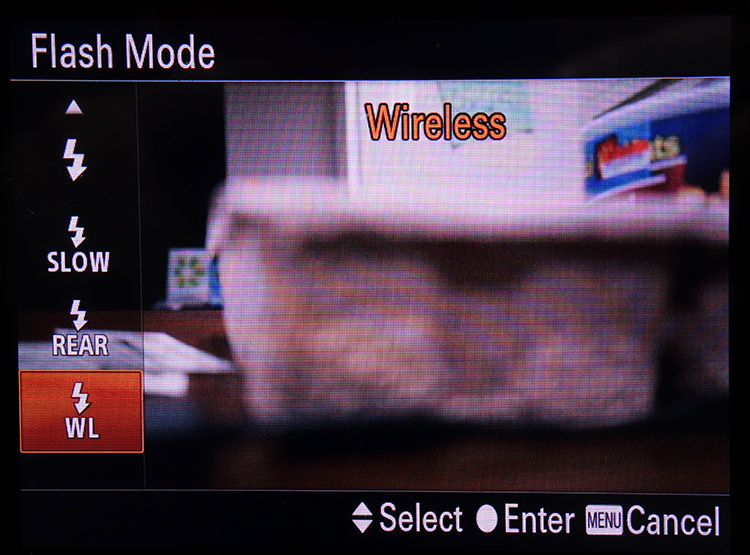

- First, we must put the Slave flash into wireless mode. The easiest way to do this is to mount it on top of the camera, turn it and the camera on, and then put the camera into Wireless mode via MENU -->

3 --> Flash Mode --> Wireless (Figure 13-12). (Or you can access it via the Fn menu.)

3 --> Flash Mode --> Wireless (Figure 13-12). (Or you can access it via the Fn menu.)

- Press the shutter release button halfway. This makes the camera communicate all the necessary settings to the flash.

- Remove the flash from the top of the camera. The large red LED on the front of the flash will start blinking once a second, telling you that 1) the camera was successfully set to wireless mode, and 2) that the flash is fully charged and ready to fire.

Figure 13-13: A photographer has good light wherever he or she goes! |

|

- Mount another flash atop the camera to act as the Master. (Again, I recommend the “F20M” for this purpose.)

- You can now place the slave flash(es) almost anywhere in the room (as long as it can see the control signals from the master), aim it at your subject, bounce it off the wall, aim it at the background, or [insert your own ideas here]. If the strength of the reflected pre-flash signals are adequately strong (as described in the previous section), the system will do its best to make sure the exposure comes out correctly.

- To make sure that the master and the slave flash can talk to each other, you can do a quick flash communications test. Press the camera’s AEL button once. The master flash will emit a quick pulse, and then half a second later the slave flash (if it can see the control pulses coming from the master flash) will respond with a short pulse of its own.

- Shoot away!

With this setup, you can have one or many slave flashes in the room – and when you take the picture they will all fire with the same intensity.

TIP: When testing the Master --> Slave communication via step 6 above, you might have to press the AEL button a second time if you have MENU -->  7 --> Custom Key(Shoot.) --> AEL button set to AEL TOGGLE. (Otherwise it will lock the f/stop and shutter speed for wherever your camera was pointing when you pressed AEL the first time.) 7 --> Custom Key(Shoot.) --> AEL button set to AEL TOGGLE. (Otherwise it will lock the f/stop and shutter speed for wherever your camera was pointing when you pressed AEL the first time.) |

Figure 13-14: The simplest wireless flash setup, where all the illumination comes from the slave flash. |

|

That’s it! Put your flashes all over the room, and experiment with placement of the light. Create emotion by simulating a sunrise. Highlight only someone’s hair and have the rest of them be a silhouette. Light them from beneath to give that classic Hollywood “Bad Guy” lighting. In short, add drama to your pictures just by moving the light around!

TIP 1: The F60 flash will beep twice after it’s fired wirelessly – the first time (short beep) means “the exposure was OK”; the second time (longer) means the flash is fully charged and is ready to shoot again. (This can be disabled via the flash’s menu, but in the studio shooting kids I find this audio feedback useful.) TIP 2: The F20 flash, while very convenient as a wireless flash trigger, has very poor battery life. Batteries in the unit will also tend to self-discharge even when sitting unused on a shelf. If you’re going to be using this for an important shoot, take a ton of extra AAA batteries with you! |

13.6 The New Wireless Protocol

This will be a short section. Sony created a “new” wireless flash protocol whose primary benefit is to be able to control multiple groups of flashes at once, and also the automatic implementation of ratio flash. But its implementation is very abstruse and difficult to understand, and if I were to write a tutorial on how to use it (which I have done), your eyes will glaze over.

Figure 13-15: There are two ways to get effortless ratio flash: The easy way using the “old protocol”, and the difficult way using the “new protocol”. The old way is easier. |

|

And so let me give you a one sentence instruction on how to do ratio flash without having to use the new protocol: Get two flashes, and put one further away from your subject as the other. Voila!

If you’re not satisfied with that, here’s a link to the writeup on how to use the new wireless flash protocol taken from an earlier book. I’m putting this information in an outside document because this book is already too long as it is, and I know from reader feedback that the level of interest is relatively low. Here’s the link: http://bit.ly/1Q5NPrC

3--> Flash Comp. menu. If you should adjust both, the total of the two settings gets implemented, although the back of the flash and the camera’s menu will only show you their respective individual values.

3--> Flash Comp. menu. If you should adjust both, the total of the two settings gets implemented, although the back of the flash and the camera’s menu will only show you their respective individual values.

7 --> Custom Key(Shoot.) --> AEL button

7 --> Custom Key(Shoot.) --> AEL button