Theory

The principles and theories that underlie cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) derive from several different sources that have become interwoven with each other as CBT has developed from its initial behavioral routes to the contemporary cognitive–behavioral integration. After presenting the overarching goals of CBT, this chapter outlines the ways in which each set of theoretical principles conceptualizes maladaptive behaviors, emotions, and cognitions and their modification. First is learning theory, including classical conditioning and instrumental conditioning principles. Next is social learning theory, which provides a cognitive theory for behavioral change. Finally, cognitive appraisal theory is presented. Relational frame theory, which underpins acceptance and commitment therapy, is beyond the scope of this review (but see Hayes & Lillis, 2012; Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999). Ways in which these theories overlap and accommodate each other are described. As previously noted, the more behaviorally oriented clinician will draw mainly from learning theory in conceptualizing a presenting problem and formulating a treatment plan, whereas the more cognitively oriented clinician will favor the theory and principles of cognitive appraisal. The cognitive–behavioral clinician can comfortably draw from both learning theories (including social learning theory) and cognitive appraisal theory to conceptualize a problem and formulate a treatment plan.

GOALS

Broadly speaking, the goal of CBT is to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life through the replacement of maladaptive emotional, behavioral, and cognitive response chains with more adaptive responses. Underlying this goal is the notion that problem behaviors, cognitions, and emotions have been acquired at least in part through experience and learning and therefore are open to modification through new experience and learning.1 The target of CBT is to teach new ways of responding and to develop new learning experiences that together promote more adaptive patterns of behavioral, affective, and cognitive responding. Also, these changes are attempted within relatively brief periods of time; in other words, CBT aims to be not only problem focused but also time limited.

Another goal of CBT is for long-term positive effects that are self-maintaining. Thus, learning experiences are repeated, and new ways of responding are practiced over a sufficient number of occasions and contexts that they become the major determinants and preferred methods of responding in the long term, independent of the therapy context. In this way, CBT aims to tool clients with their own repertoire of skills for dealing with problematic situations and thereby become less and less dependent on, and eventually autonomous from, the therapist.

These two overarching goals are achieved within the framework of a set of guiding principles of behavioral theory and science and cognitive theory (and more recently, cognitive science) for conceptualizing presenting problems and formulating intervention strategies. These principles drive another goal, which is to use an individually based functional analysis of the causal relations among cognitions, behaviors, emotions, and environmental and cultural contexts for tailoring intervention strategies specifically to the needs of a given problem. Thus, rather than assuming that one standard treatment fits all, CBT is based on careful observation and understanding of each individual’s presenting problem. Functional analysis refers to an analysis of not only the instrumental antecedents and consequences but also which stimuli are producing which conditional responses (CRs), which cognitions are contributing to behaviors and emotions, and within which environmental and cultural contexts these occur. The therapist and client then make an informed choice about which methods for behavioral and cognitive change to use from a variety of different intervention strategies. Another goal is to have a flexible approach to implementation, which is facilitated by ongoing evaluation and modification of cognitive–behavioral intervention strategies as appropriate. Linked with this is the aim of engaging the client in the process of experimentation and ongoing evaluation of the effectiveness of the chosen interventions. Evaluation not only permits revision to the intervention strategies where necessary but also provides an assessment of overall progress. Overall progress is measured by agreed-upon markers between the client and the therapist, and when the evidence indicates lack of progress, consideration is given to alternative treatment methods. Clearly, this entails therapist–client collaboration in formulating and implementing a treatment plan and a highly active orientation on the part of the client.

KEY CONCEPTS

This section is divided into key concepts of learning theory (classical and instrumental conditioning), social learning theory, and cognitive appraisal theory. The ways in which these theories overlap and accommodate each other are described as well.

Learning Theory: Classical Conditioning

Classical (or respondent) conditioning depends on innately evocative stimuli (US) producing an unconditional, reflexive response (UR), such as when physical injury reflexively produces a pain grimace. When a neutral stimulus is paired with the US, the neutral stimulus becomes a conditional stimulus (CS) with powers to elicit a CR that resembles the original UR (Pavlov, 1927). For example, in the case of persons undergoing chemotherapy (US) that causes them to vomit (UR), the nurse may become a CS by association with administration of the chemotherapy. Consequently, sight of the nurse may produce conditional nausea in the patient even before the chemotherapy is administered the next time. Furthermore, through a process of generalization, the CR will emerge in reaction to stimuli similar to the original CS, where similarity includes perceptual, categorical, or symbolic/semantic features. Following from the preceding example, generalization may result in conditional nausea in response to seeing the medical clinic or administrative staff, medical procedures in general, or even just reference to illness. In addition, Pavlov (1927) demonstrated that if the CS is presented enough times without the US, the CR lessens or extinguishes. Continuing the example, once the chemotherapy course has completed, repeated visits to the clinic for checkups would result in an eventual diminution of the conditional nausea response.

The principles of aversive classical conditioning are applied mostly to anxiety disorders. Early theorizing of fears and phobias relied on contiguous classical conditioning models, in which a neutral stimulus develops conditional fear-provoking properties simply by virtue of close temporal pairing with an aversive stimulus. Examples include ridicule and rejection by a peer group leading to conditional fear (i.e., phobia) of social situations or barking by a ferocious dog leading to phobias of dogs. These early theories were criticized for being too simplistic (e.g., Rachman, 1978), especially as not everyone who undergoes an aversive experience develops a phobia. That is, not everyone who is ridiculed by a peer group develops social phobia, and not everyone who is barked at by a ferocious dog develops a phobia of dogs. Recent revisions to classical conditioning models of fear and anxiety (see Mineka & Zinbarg, 2006, for a review) correct the earlier pitfalls.

Subsequent models continued to emphasize the role of aversive experiences in the formation of conditional anxiety responses, but instead of being limited to direct experience with negative events, they extended to conditioning through vicarious observation of negative events or even informational transmission about negative events (see Mineka & Zinbarg, 2006, for citations of supportive research). For example, observing as someone else is physically injured, or being terrified in a car accident, may be sufficient for the development of a conditional fear of motor vehicles, as would being told about the dangers of driving and the high likelihood of fatal car accidents. Vicarious and informational transmission of conditioning represents the incorporation of cognitive processes into classical conditioning models. The newer conditioning models also recognize that a myriad of constitutional, contextual, and postevent factors moderate the likelihood of developing a conditional phobia after an aversive event.

Constitutional factors (or individual difference variables) include temperament. For example, individuals who tend to be more nervous in general are believed to be more likely to develop a conditional phobia after a negative experience than less “neurotic” individuals who undergo the same negative experience. That neuroticism is heritable may also explain the preliminary evidence for heritability of fear conditioning (Hettema, Annas, Neale, Kendler, & Fredrikson, 2003). Animal modeling suggests that early life adversity is another predisposing factor to fear conditioning. Low rates of estrogen in women, which have been related to impaired extinction (the reduction of conditional fear through repeated presentations of the conditional stimulus in the absence of an aversive outcome, described in the section Principles of Treatment), may be another constitutional factor that contributes to more sustained conditional fear in women. Another constitutional factor is personal history of experience with the stimulus that is subsequently paired with an aversive event, as prior positive experience may buffer against the development of a conditional phobia. For example, the effects of observing one parent react fearfully to heights may be buffered by having previously observed other family members react without fear to heights. Recognition of individual difference factors addresses the earlier criticism that not everyone who undergoes an aversive experience develops a phobia; rather, certain individuals are prone to developing conditional phobic responses following an aversive experience as a function of their temperament and life experience.

Contextual factors at the time of the aversive experience include intensity and controllability: More intense and less controllable negative events are more likely to generate conditional fear than less intense and/or more controllable negative events. According to these premises, individuals trapped for a lengthy period of time inside an elevator stuck between floors would be more likely to develop a conditional fear of elevators than the person who can escape from a stuck elevator relatively quickly. Similarly, soldiers at the front line of combat would be more likely to develop conditional fear than those further away. Another contextual factor pertains to principles of preparedness, or the innate propensity to rapidly acquire conditional fear of stimuli that posed threat to our early ancestors (Seligman, 1971). Examples of such stimuli are heights, closed-in spaces from which it is difficult to escape, reptiles, and signals of rejection from one’s group. Thus, as a species, humans are more likely to develop long-lasting conditional fears following negative experiences in prepared situations (e.g., being laughed at by peers) compared with other, “nonprepared” situations (e.g., being shocked by an electric outlet). Preparedness is believed to account for the nonrandomness of phobias, or the fact that some objects or situations are much more likely to become feared than others.

Following conditioning, a variety of postevent processes may influence the persistence of conditional fear, including additional aversive experiences, expectancies for aversive outcomes (Davey, 2006), and avoidant responding. For example, the child who is teased by a peer group, then ruminates about being teased, expects further teasing, and avoids the peer group is more likely to develop social anxiety than the child who undergoes the same teasing but returns to the peer group the next day. In sum, contemporary models of classical conditioning recognize that the development of an excessive and chronic conditional fear is not explained by a specific aversive event in isolation but by an interaction among predisposing features, the aversive event, and reactions to the event.

Attention has been more recently given to processes of generalization, with those at risk for anxiety being more vulnerable to generalization of fear following an aversive event to stimuli that resemble the original conditional stimulus (perceptually, categorically, or symbolically) or to stimuli that occur in the same context as the aversive event but themselves do not predict aversive events (i.e., cues that are never directly paired with a US). These processes appear to contribute to the spread of fears that characterize anxiety disorders. As an example, a child prone to anxiety may develop fears not only of a bully on the playground but also other children on the playground as well. Weakened extinction is another characteristic of individuals with or at risk for anxiety disorders, and likely contributes to the persistence of phobias; following the prior example, the child fails to lessen his or her fear of the bully even after many encounters in which the prior bully is no longer threatening.

The classical conditioning model is also applicable to disorders related to substance use, in which the principles of appetitive conditioning apply, as well as aversive conditioning. Appetitive conditioning refers to conditioning with a US that produces an innately positive response, whereas aversive conditioning refers to conditioning with a US that produces an innately negative response. In the case of substance use disorders, euphoria serves as an innately positive UR to the drug. Over time, environmental stimuli present during the euphoric state become conditional. These environmental stimuli may be the locations in which the drugs are usually consumed or the people with whom drug taking normally occurs. Consequently, the environmental stimuli elicit conditional urges or cravings to take more of the drug. Known as the conditioned appetitive motivational model of craving (Stewart, de Wit, & Eikelboom, 1984), this model explains the difficulties experienced when recovering drug users return to the environments in which they originally developed their drug dependence. That is, just seeing a group of friends with whom drugs used to be taken may be enough to produce cravings for the drugs, even though the drugs themselves are not present.

Siegel (1978) proposed the conditional compensatory response model, a classical conditioning model of drug tolerance. In this model, environmental stimuli associated with drug intake become associated with the drug’s effect on the body and elicit a CR that is opposite to the effect of the drug, driven by an automatic drive for body homeostasis. As this CR increases in magnitude with continued drug use, the drug’s effects decrease and tolerance increases. Finally, aversive classical conditioning has been evoked as an additional mechanism by which stimuli associated with the unpleasant periods of drug withdrawal elicit withdrawal-like symptoms. For example, if withdrawal is typically experienced upon waking from sleep, then waking may elicit conditioned withdrawal symptoms that in turn could drive continued drug use to minimize withdrawal effects.

Principles of Treatment

The treatment model that derives from classical conditioning states that behaviors and emotions can be changed by disrupting the associations that have formed between a cue (CS) and either an aversive or a pleasant outcome (US). In learning theory, this is referred to as extinction. Conditioning involves pairings of the CS with the US; extinction involves repeated presentations of the CS without the US. The corresponding treatment is referred to as exposure therapy; in this therapy, the client repeatedly faces the object of fear (in the case of anxiety disorders) or the drug-related cue (in the case of substance use disorders) in the absence of an aversive or a pleasant outcome. As an example, individuals with social anxiety would be encouraged to repeatedly enter social situations without being ridiculed or rejected, or individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder would be encouraged to repeatedly enter places where they were previously traumatized without being retraumatized. As another example, individuals who drink alcohol excessively would be exposed to substance cues (e.g., sight or smell of alcohol) and prevented from consuming the alcohol so that the CS is repeatedly presented in the absence of reinforcement that comes from the consumption of the drug. This is called cue exposure.

Several mechanisms are believed to underlie extinction and thereby exposure therapy. One such mechanism is habituation (or decreased response strength simply as a function of repeated exposure). Another mechanism, inhibitory learning, is considered to be even more central to extinction (Myers & Davis, 2007). Inhibitory learning means that the original association between a CS and aversive event is not erased throughout extinction, but, instead, a new inhibitory association (or expectancy) is developed. For example, as a result of exposure therapy for fear of dogs, an original excitatory association between a dog and ferocious barking would be complemented by a new inhibitory association between a dog and the absence of ferocious barking. Consequently, as a result of exposure therapy, two sets of associations exist in memory. Once exposure therapy is over, the level of fear that is expressed when a dog is encountered in daily life will depend on which set of associations is evoked. Interestingly, basic research by Bouton and colleagues (as reviewed in Bouton, Woods, Moody, Sunsay, & García-Gutiérrez, 2006) indicates that context is important in determining which set of associations is evoked. If the previously feared stimulus is encountered in a context that is similar to the extinction/exposure therapy context, then the inhibitory association will be more likely to be activated, resulting in minimal fear. However, if the previously feared stimulus is encountered in a context distinctly different from the extinction/exposure therapy context, then the original excitatory association is more likely to be activated, resulting in more fear. Following the example of dog phobia, assume that the exposure treatment was conducted in a dog training center. Then, once treatment is over, a dog is encountered on a neighborhood sidewalk, a context that is distinctly different from the dog training center. On the sidewalk, the original excitatory fear association is more likely to be activated than the new inhibitory association that was developed throughout exposure treatment, resulting in the expression of fear.

Thus, a change in context is presumed to at least partially account for the return of fear that sometimes occurs following exposure therapy for anxiety disorders (Craske et al., 2008, 2014) and relapse following treatment for substance use disorders (e.g., Collins & Brandon, 2002). In addition to context, other factors can also reactivate the original excitatory association. One such factor is being exposed to a new negative experience. Thus, persons who are successfully treated for their fear of dogs may have their fear return if they subsequently experience a painful event, such as falling and injuring themselves on a hiking trail, and then encounter a dog on a hiking trail (in learning theory, this is called reinstatement) or if they are barked at by another ferocious dog (termed reacquisition).

Innovative strategies are now being tested for enhancing new inhibitory associations throughout exposure therapy (see Craske et al., 2008, 2014, for reviews). In addition, attention is being given to ways of enhancing the retrievability of new inhibitory associations once exposure therapy is completed, and thereby decreasing relapse, such as conducting exposure therapy in multiple contexts. Another is to provide retrieval cues that remind clients, when they are outside of the therapy context, of the new learning that took place in the therapy context or at least recommend to clients that they actively try to remember what they learned when in the therapy context (see Craske et al., 2014).

Another key concept associated with extinction of CRs is safety signals, or conditional inhibitors that predict the absence of the aversive stimulus. When the conditional inhibitor is present, the CS is not paired with the US; when the conditional inhibitor is not present, the CS is paired with the US. In the experimental literature, safety signals alleviate distress to the CS in the short term, but when no longer present, fear to the CS returns (Lovibond, Davis, & O’Flaherty, 2000). Common safety signals for anxiety disorder clients are the presence of another person, therapists, medications, food, or drink. Thus, clients with panic disorder and agoraphobia may feel relatively comfortable walking around a shopping mall with a bottle of medications in their pocket (even if the medications are never taken) but report being anxious in the shopping mall when without the bottle of medication. Despite the relief they provide in the short-term, conditional inhibitors have been shown to interfere with extinction learning in human experimental studies (e.g., Lovibond et al., 2000).

Several studies have evaluated safety signals in phobic samples (see Craske et al., 2014, for a review). For example, claustrophobic participants who are encouraged to use safety signals during exposure to being inside a small booth report more fear at later testing to the claustrophobic booth without the safety signals than those who complete exposure without safety signals. (The safety signals were to open a window on the side of the booth and to check that the booth door unlocked.) Just the perception of safety (i.e., knowing that the safety signals were available even though they were not used) has the same detrimental effects on outcome as the actual use of safety signals. Occasional failures to replicate these detrimental effects may be due to methodological reasons (see Craske et al., 2014). Thus, exposure therapy typically proceeds by having clients repeatedly face their feared objects or situations while being weaned from typical safety signals.

Role of Cognitive Variables in Classical Conditioning

In its earliest form, classical conditioning was construed as largely mechanistic and reflexive, with little room for the role of cognition. However, the model has evolved over time to incorporate cognitive factors. The “cognitive revolution” can be attributed to researchers such as Tolman (1948), who challenged purely mechanistic models, and Rescorla (1968), who established that conditioning involves the acquisition of information, so that CRs are elicited when the CS predicts that the US is likely to occur and are inhibited when it predicts that the US is less likely to occur. Contemporary models generally dictate that the CS activates a memory representation of the US and an expectation of its occurrence (see Kirsch, Lynn, Vigorito, & Miller, 2004, for a review). An expectancy is a future-oriented belief.

Expectancies may be implicit (automatic) or explicit (conscious), and debate continues as to the necessity of explicit expectancies in conditioning (Kirsch et al., 2004). The more mechanistic view dictates that although explicit expectancies may be produced by conditioning trials, they are not necessary for conditioning. In support, conditioning can occur to a CS that is not consciously perceived, and when the relationship between a CS and US is unknown, at least with prepared CSs (see Öhman & Mineka, 2001). The alternative point of view dictates that explicit expectancies mediate the effects of conditioning and cause the CR. In support, simply informing participants about a relationship between a CS and US can produce a CR (previously referred to as informational transmission), just as instruction alone can produce extinction of a CR. In addition, strength of the CR varies as a function of information about the intensity of the US (Kirsch et al., 2004). Hence, CRs be influenced by both mechanistic/automatic and higher order cognitive processes (e.g., Öhman & Mineka, 2001).

Recognition of the role of cognitive factors in classical conditioning provided a pathway through which cognitive theories could be intertwined with learning theories. For example, an abundance of evidence points to biases in the expectancies of individuals with anxiety disorders, including overattention to negative stimuli, overestimation of the likelihood of negative events, and catastrophizing the meaning of negative events (see Davey, 2006). Hence, the anxious person may hold particularly high expectancies for an intensely aversive experience, which in turn contributes to the acquisition of conditional responding or interferes with its extinction (Davey, 2006). In other words, maladaptive assumptions and beliefs may contribute to the perceived intensity of the US or the perceived likelihood of its reoccurrence, which in turn mediates stronger conditioning. Furthermore, correction of these expectancy biases, as would be achieved through cognitive therapy, can be easily incorporated into exposure therapy as a means of enhancing extinction of CRs. That is, cognitive skills for learning to decrease the estimated likelihood of negative events or the perceived intensity of the negative event should enhance extinction of CRs during exposure therapy. Davey (2006) referred to these as cognitive revaluation strategies, or strategies for changing the outcome expectancy of an aversive event and for devaluing its aversiveness.

In the case of substance use disorders, research similarly indicates that expectancy biases may enhance appetitive conditioning. For example, an inflated expectancy for drugs to have positive effects, such as improving mood state, has been shown to be related to the development of substance-related problems (e.g., G. T. Smith, Goldman, Greenbaum, & Christiansen, 1995). These positive expectancies may enhance appetitive conditioning and again be an appropriate target during cue exposure.

Learning Theory: Instrumental Conditioning

Whereas classical conditioning principles are based on the association between a neutral stimulus and an innately evocative stimulus, instrumental conditioning principles are based on the consequences of a response and their effect on the future occurrence of that response. The basic law of learning that was originally formulated by Thorndike (1932) stated that responses followed by a “satisfier” strengthen the association between the response and the situation in which it occurred. Thus, the response would be more likely to occur in that situation in the future. As an example, if a child’s oppositional behavior is followed by parental attention, then the oppositional behavior will be more likely to occur in the presence of the parent in the future. If a response is followed by an “annoyer,” then the association is weakened, so that the response would be less likely to occur in that situation in the future. As an example, if a child’s oppositional behavior is ignored, it will be less likely to occur in the future. Skinner (1938) developed and refined Thorndike’s theory; he rejected Thorndike’s notion of “satisfaction” and introduced his operant theory of behavior, in which the term operants describes classes of behavior that operate on the environment to produce certain consequences.

The consequences of behavioral responses are categorized according to their effects: Reinforcers cause a behavior to occur with greater frequency, and punishers cause a behavior to occur with less frequency. Reinforcers and punishers are either positive, meaning they are delivered followed a response, or negative, meaning they are withdrawn following a response. Thus, an event presented immediately following a behavior that causes the behavior to increase in frequency is called a positive reinforcer. For example, sensory stimulation effects are believed to be a positive reinforcer for many repetitive habits, such as hair pulling; in other words, hair pulling is more likely to happen in the future because it is followed by sensory stimulation. An event that increases a behavior by virtue of its withdrawal is called a negative reinforcer. For example, reduction of distress maybe a negative reinforcer of compulsive behaviors in persons with obsessive compulsive disorder; in other words, they are more likely to engage in compulsive behaviors in the future because the compulsive behavior is followed by feeling less distressed.

Any event presented immediately following the behavior that causes the behavior to decrease in frequency is called a positive punisher. These include physical punishers, such as unpleasant odors, which have been used as punishers of inappropriate sexual urges, and verbal punishers, such as a stern “no” from a parent in response to a child’s oppositional behavior. Negative punishment occurs when a behavior is followed by the removal of something positive, so that the behavior is less likely to occur again. An example is the removal from a situation in which one would otherwise be able to earn reinforcers, as is the case when children are assigned to time out for oppositional behavior. Another example of a negative punisher is the deduction from a person’s collection of reinforcers, also termed response cost, as is sometimes used in behavioral diet and exercise programs; for example, if more than a maximum number of calories is consumed, or if less than a minimum amount of exercise is completed, the client agrees to give her own money to a nonpreferred charity. Extinction is the lack of any consequence following a behavior; inconsequential behavior, without any favorable or unfavorable consequences, will lessen in frequency.

The effectiveness of reinforcers and punishers is influenced by factors such as satiation, or the degree to which the individual’s appetite for the consequence has been already satisfied. For example, food is sometimes used as a reinforcer for shaping verbal skills in children with autism; the effectiveness of the food reinforcer will be enhanced if the training is conducted when the child is hungry. Another factor is immediacy, with more immediate consequences having greater impact than more distal consequences. Thus, a parent’s verbal reprimand of a child’s misbehavior will be more effective as a positive punisher if delivered immediately after the misbehavior, compared with at the end of the day. Contingency is another factor, meaning that the reliability with which the consequence follows the behavior increases its impact. For example, token reinforcers (or secondary reinforcers, which can be later exchanged for a primary reinforcer, such as food) that are delivered only some of the intervals of time in which drug abusers successfully abstain from drug use will be less effective than if they were delivered every interval of time in which abstention occurred. Finally, size of the consequence is important, with larger consequences having greater impact than smaller ones.

A good example of the application of operant principles to the understanding of psychopathology is in the area of depression. Specifically, Lewinsohn (1974) and colleagues attributed depressed mood to a low rate of response contingent positive reinforcement. Insufficient reinforcement in major life domains is presumed to lead to dysphoria and a reduction in behavior (i.e., motor retardation). Three main sources of low rates of positive reinforcement were recognized. First, the environment may produce a loss of reinforcement or be inadequate in providing sufficient reinforcement. For example, loss of a job would produce a loss of reinforcement, and chronic lack of employment would represent continuing lack of reinforcement. Second, the individual may lack the skills needed to obtain reinforcement that is potentially available. This would be the case for the person who lacks social skills and therefore misses out on the positive reinforcement from social relationships. Third, reinforcers may be available, but the individual is unable to enjoy or receive satisfaction from them, as would occur for an individual who is highly anxious in social situations to the point that the anxiety interferes with the natural positive reinforcement from social relationships. In terms of depression, it is further recognized that the negative mood may elicit positive reinforcement from others in the form of concern, resulting in the individual’s receiving reinforcement for behaving in a depressed manner. Such reinforcement may contribute to the maintenance of depressed behavior. However, over longer periods of time, the initial concern that is expressed by others often shifts to aversion (because continued depressed behavior eventually becomes unpleasant), resulting in eventual alienation and the withdrawal of positive reinforcement from others. Hence, an individual who is depressed lacks positive reinforcement for nondepressed behaviors, is initially reinforced for depressed behaviors, and then eventually loses reinforcement for any kind of behavior.

Another application of operant principles is in disorders related to substance use. Drug use is believed to be maintained by the positively reinforcing effects of the physiological effects of the drugs, as well as social reinforcement, such as peer approval, that is given to a drug-abusing lifestyle. In addition, the escape that drugs provide from life stressors, negative mood states, or even the withdrawal effects from the drugs themselves negatively reinforce drug-taking behavior.

Principles of Treatment

In approaches to treatment that rely upon operant methods, a functional analysis is conducted to evaluate the factors that may be contributing to excesses of maladaptive behavior and/or deficits of adaptive behaviors, and interventions are designed to alter the antecedents to behaviors, and to use reinforcers to enhance adaptive behaviors and punishers or extinction to decrease maladaptive behaviors. More specifically, the functional analysis establishes the causal relations between antecedents to a behavior, the behavior, and the consequences of a behavior. For example, as described by Farmer and Chapman (2008), bulimia might involve antecedent events of conflict with significant others and proximity to a food market that precede the behavior of overeating. This behavior is positively reinforced by the immediate gratification of eating. The subsequent discomfort from overeating then becomes an antecedent to the next behavior of purging, which in turn is followed by negative reinforcement of reduction in discomfort. The positive reinforcement of immediate gratification of eating and the negative reinforcement of reduction of discomfort through purging increase the likelihood of the bingeing and purging cycle in the future. Understanding the “behavioral contingencies” of any given problem behavior is essential to effective treatment planning.

A behavior is said to be under stimulus control when it occurs in the presence of a particular stimulus and not in its absence. Following the previous example, the bulimic behavior may occur only in relation to conflict with a significant other. In this case, conflict with others becomes a discriminative stimulus for the behavior of overeating. Often the discriminative stimuli are moderated by other ongoing contextual variables, such as time of day and mood state, so that the relationships become relatively complex. In the aggregate, the discriminative stimuli and associated conditions function to signal the likelihood of reinforcing or punishing consequences of the behavior. Another type of antecedent is termed establishing operations, or events or biological conditions that alter the reinforcing or punishing consequences. Continuing with the example of bulimia, having recently dieted may serve as an establishing operation that magnifies the likelihood of immediate gratification from overeating (i.e., the principle of satiation) in the presence of the cue of conflict with others. The role of discriminative stimuli and establishing operations is included in the behavioral contingency formulation, which is then used to develop a treatment plan.

Behavioral contingency management involves changing the antecedents of the target behavior, such as removing or avoiding the antecedents that typically elicit problem behaviors. This strategy is typically included in treatments for disorders related to substance use in which abusers are asked to avoid drug-associated people, places, and stimuli. Also, it may be used when self-injurious behaviors are under the control of certain antecedent stimuli. When the antecedent stimulus cannot be avoided completely, another strategy is to modify it. For example, recovered alcohol abusers may not be able to fully avoid peers with whom alcohol was previously consumed; in this case, the peers (the antecedents) may be asked to refrain from encouraging the recovered person from drinking. Another strategy involving antecedents is to use stimulus cues to encourage adaptive behaviors, such as “coping cards” to remind clients to engage in particular behaviors. In discrimination training, reinforcers for behaviors are given in certain situations but not in other situations, so that individuals learn in which situations particular behaviors are appropriate (if reinforced) or not (if not reinforced). As an example, in the context of anxiety disorders, approach behavior toward nondangerous situations (e.g., walking alone during the day in a safe park) would be reinforced whereas approach to truly dangerous situations (e.g., walking alone at night in a violent crime district) would not. Discrimination training can be applied to emotional states as well, such as learning to accurately discriminate between tension and relaxation, or anger and anxiety. Another strategy is to arrange establishing operations that change the value of reinforcers, as occurs when methadone decreases the reinforcement value of heroin use (by blocking the high from heroin) or when regulation of eating to four to six times a day decreases the reinforcement value of binging. Similarly, satiation therapy involves overdelivery of reinforcers that in turn is presumed to decrease their value. For example, smoking cessation programs sometimes include a period of oversmoking to decrease the reinforcement value of the nicotine.

Another set of principles for behavioral contingency management involves altering the consequences of behavior. Consequences are applied to either increase the likelihood of a desired behavior occurring again in the future (reinforcers) or decrease the likelihood of undesirable behaviors in the future (punishers), keeping in mind the factors already described as being influential, such as immediacy, size, and contingency of the consequence. An example of applying a positive reinforcer would be to praise a child who bravely approaches an anxiety-provoking situation. Interventions designed to decrease a target behavior may include extinction, or removing reinforcers that previously maintained the behavior. An example would be removal of parental attention from a child’s display of oppositional behavior. Alternatively, punishers may be administered, such as negative punishers in the form of response cost (e.g., time out for oppositional behavior in children) or positive punishers as in covert sensitization procedures (Cautela, 1967). In the latter, an undesired behavior is paired in imagination with aversive states, such as pairing alcohol consumption with nausea and vomiting. Covert sensitization also includes negative reinforcement in the form of relief from the aversive state as the undesired behavior is replaced by a desired behavior.

For contingency management to work, reinforcers for adaptive behaviors must exceed the reinforcers for maladaptive behaviors. Thus, if reinforcement for consuming alcohol is more potent and immediate than it is for engaging in behaviors that do not involve alcohol, such as exercising or other forms of social recreation, then the individual will devote more time and energy to consuming alcohol. Obviously, the challenge for treatment is to make the reinforcements for adaptive behavior more influential than the reinforcements for maladaptive behavior.

As outlined by Farmer and Chapman (2008), “the primary assumption underlying contingency management interventions is that the target behavior in question is under the influence of direct-acting environmental antecedents or consequences” (p. 108). Contingency management procedures are not as effective for rule-governed behavior or for behavior that is not controlled by the environmental antecedents or consequences but instead is controlled by rules. Farmer and Chapman gave the example of a person with anorexia who restricts intake of food based on a rule that “by not eating, I will lose weight and be more attractive to others.” This rule implies that thinness is associated with a variety of social reinforcers. However, the rule may be at odds with actual social reinforcement patterns because others may not respond to thinness as being more attractive. Hence, the behavior of food restriction becomes more of a rule-governed behavior. In this case, behavioral contingency interventions are not useful, and direct challenges to rule governing would be more appropriate.

Another assumption of behavioral contingency programs is that the individual has the target behavior in his/her repertoire. If, for example, the target behavior is to refuse peer pressure to use drugs, and the individual lacks skills of assertive communication, then reliance on changes to the reinforcers and punishers of the desired behavior will have little effect. Instead, other principles would be used to develop new behaviors of assertiveness, such as response shaping and building skills. Response shaping is designed to develop behavioral skills through successive approximation to an end goal, with reinforcement for each approximation along the way. For example, in biofeedback treatment for headaches, individuals learn to lower their muscle tension. Each time their muscle tension is successfully lowered by a specified degree, an audio or visual signal is displayed, which reinforces the successful reduction in muscle tension. Over time, the amount by which the muscle tension has to reduce to be reinforced progressively increases (i.e., successive approximation). Another example of shaping is the training of communication skills in the context of severe developmental disorders; positive reinforcers are provided first for any vocalization, followed by reinforcement for vocalization of a word, then a chain of words, and so on, until reinforcement applies to a full sentence. In other words, shaping involves breaking down a behavior into its components. Reinforcement is given as the client performs the initial behavior, and once that behavior is established, then reinforcement is withheld until the client performs the next behavior in the sequence.

When a certain behavior can be performed in one situation but not in another, then skills training is less relevant, and instead attention may be given to response generalization. An example might be the ability to say no to unreasonable requests from family members but not from friends. In this case, instruction and role playing may be used to help clients perform the behavior in different contexts.

Role of Cognitive Variables in Instrumental Conditioning

In instrumental theorizing, thinking can be viewed as a form of behavior and, as such, can serve several functions. Thoughts may serve as a discriminative stimulus for behaviors, such as when thoughts about the dangers of driving lead to avoidance of driving. Thoughts may serve as establishing operations that alter the perceived consequences of behavior, such as when the thought “If I drink alcohol, I will feel better” leads to increased drinking. Thoughts may also function as reinforcing or punishing consequences, such as positive thoughts about one’s success or negative thoughts about one’s failure in a given situation. Or thoughts may function as rules that govern behavior. In all of these cases, thoughts are viewed in terms of their function and not their content.

Furthermore, as with classical conditioning, early mechanistic models of operant theorizing have been replaced by expectancy models, in which conditioning is presumed to result in the formation of representations of the relationship between a response and an outcome. That is, instrumental (operant) learning situations produce expectancies that certain behaviors will produce particular outcomes (see Kirsch et al., 2004, for a review). As with classical conditioning, some evidence indicates that explicit expectancies may even mediate operant conditioning. For example, simply informing participants about response–reinforcement contingencies can produce instrumental learning, just as can information that the contingency is no longer present produce extinction. In addition, devaluing the value of the reinforcer reduces the operant responding because motivation for the outcome has presumably declined. On the other hand, on some occasions instrumental conditioning proceeds without explicit cognitive mediation. For example, in some instances devaluation of the reinforcer has no effect (see Kirsch et al., 2004). Hence, both mechanistic and explicit cognitive processes may underlie instrumental conditioning. Nonetheless, recognition of the role of expectancies in instrumental conditioning allows an integration between instrumental learning theory and cognitive theory. The expectancy for positive reinforcement and the perceived value of such reinforcement—and similarly the expectancy for punishment and its perceived value—likely represent individual difference variables that contribute to the potency of reinforcement and punishment. For example, depressed mood and lowered motivation to respond in general may be due in part to lowered expectancy of reinforcement. Similarly, a tendency to devalue received reinforcement (e.g., disregarding a compliment as “fake”) may contribute to the behavioral deficits of depression. Conversely, antisocial behavior may be due in part to lowered expectancy of punishment or lowered value of received punishment (e.g., disregard for the threat of pain from a physical confrontation). Consequently, cognitive methods could be incorporated into instrumental behavioral procedures to enhance the value of the consequences being used to modify behavior. For example, cognitive therapy that enhances the expectancy or value of positive reinforcement could be combined with behavioral exercises designed to increase positive reinforcement, whether it be exercise, social interaction, or work performance.

Social Learning Theory: Self-Efficacy Theory

Social learning theory was first proposed by Rotter (1954) but made more popular by Bandura (1969), whose research on observational learning—learning behaviors through the observation of others’ modeling such behaviors—pointed to the role of cognitive variables as powerful influences of behavior. Bandura proposed that motivation, a primary determinant of the activation and persistence of behavior, is influenced by cognitive processes of representing future consequences in thought, goal setting, and self-evaluation. As such, Bandura’s work contributed to the paradigmatic shift from purely mechanistic models of learning to more cognitive models of learning, in line with Tolman (1948) and Rescorla (1968).

A specific cognitive mediator identified by Bandura (1977) is self-efficacy, or “the conviction that one can successfully execute the behavior required to produce an outcome” (p. 193). Self-efficacy is distinct from the more general term self-confidence because self-efficacy is a situationally specific belief in being able to carry out a specific act, such as the ability to approach a feared object under specified conditions. Self-efficacy also is theoretically distinct from outcome expectancies, which refer to the perceived likelihood and valence of events. Outcome expectancies are the types of expectancies presumed to operate within classical and instrumental conditioning. Thus, Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy was a new addition to expectancy-learning theory.

In Bandura’s (1977) reciprocal determinism model, self-efficacy expectations influence choice of behaviors and determine the degree of effort expended and persistence in the face of obstacles or aversive experiences. In other words, self-efficacy is believed to influence coping in difficult situations. Self-efficacy also is purported to contribute to thoughts and emotional reactions. For example, poor self-efficacy is presumed to contribute to excessive dwelling on personal deficiencies that in turn creates stress and impairs performance by reducing concentration on the task at hand.

Skills and incentives are additional essential determinants of action that reciprocally influence self-efficacy. Positive incentives, for example, foster performance accomplishments that raise self-efficacy, as do knowledge and skills. Also, verbal persuasion, vicarious experience, and physiological arousal are assumed to influence self-efficacy. However, the strongest influence on self-efficacy was posited to derive from performance accomplishment, because it provides the most evidence for personal achievement and skills. Even so, within a reciprocal determinism model, cognitive factors can mitigate the effects of performance success, such as when success is attributed to external factors versus oneself.

Bandura (1977) proposed that all therapeutic gains are attributable to raising and strengthening percepts of self-efficacy, regardless of the specific treatment method used. However, because performance accomplishment per se was considered to be the most powerful source for raising self-efficacy, his model of therapeutic change has been applied mostly to behavioral treatments (e.g., Bandura, 1988), rather than cognitive therapy. In fact, self-efficacy theory guided a specific approach to exposure therapy for anxiety disorders called mastery exposure therapy (S. L. Williams & Zane, 1989).

Cognitive Appraisal Theory

The primary assumption of cognitive therapy is that distorted and dysfunctional thinking is the primary determinant of mood and behavior. Thus, the impact of environmental events is presumed to be mediated by the interpretations given to them. Conceptualization of the “environment” varies. Constructivists, for example, view a cognitively constructed environment as being more influential on emotion and behavior than the physical environment. Others give the physical environment equal footing with appraisals of the self or environment. However, all cognitive theorists assume that distorted thinking is common to all psychological disorders. Each disorder or each individual is characterized by a set of specific distortions and underlying core beliefs. Thus, a content approach to cognition is taken to emphasize the stated beliefs and appraisals. Two main cognitive theories are reviewed in the following section: rational emotive–behavior therapy (e.g., Ellis, 1962) and cognitive therapy (e.g., Beck, 1976).

Ellis and Rational–Emotive Behavior Therapy

Ellis, like Beck, was originally trained in psychoanalysis but became dissatisfied with the inefficiency of that approach. His own approach was based on the ancient Stoic philosophy of Epictetus (and the like), who stated that facts do not upset people, but rather people upset themselves with the view that they take of those facts. Ellis (1962) believed that emotional reactions are mediated by “internal sentences,” or thoughts, and that maladaptive responses reflect the internal sentences becoming indiscriminate and resulting in situations being labeled irrationally. Thus, even though an emotional reaction may be appropriate to the label that is attached to a situation, the label itself may be inaccurate. For example, a situation may be labeled as dangerous, in which case a fear response is appropriate, and yet the situation is not truly dangerous and therefore the label is inappropriate. Ellis (1962) suggested that such labeling of situations derives from a set of ideas that are irrational, meaning that they are not likely to be supported or confirmed by the environment, and that they lead to inappropriate negative emotions in the face of difficulty. Irrational ideas in turn are presumed to derive from various socialization experiences. Rational beliefs, or beliefs that promote survival and happiness and are likely to find empirical support in the environment, lead to appropriate emotional and behavioral responses to losses and difficulties.

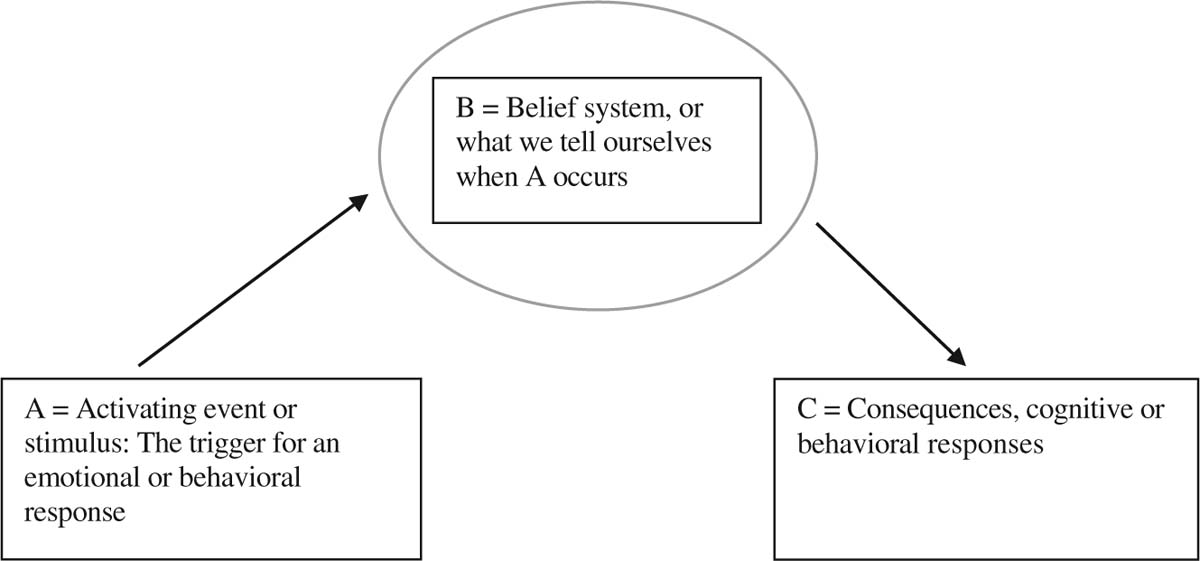

Ellis (1957) proposed an ABC model of psychological functioning and disturbance, in which A represents undesirable activating events being experienced; B represents the rational and irrational beliefs about the event; and C represents consequences, either the appropriate emotional and behavioral consequences created by rational beliefs or the inappropriate and dysfunctional consequences created by irrational beliefs. This model is shown in Figure 3.1.

Thus, activating events (A) do not directly cause emotional and behavioral consequences (C); instead, beliefs (B) about those events are the most critical causes of the consequences. In his own words, Ellis (2003) characterized irrational beliefs as being rigid and extreme, inconsistent with social reality, illogical or nonsensical, demanding and “musturbatory” (i.e., must statements), “awfulizing and terribilizing” (i.e., catastrophizing), and depreciative of human worth. They represent implicit assumptions that determine how individuals judge themselves and others, and they become automatic and seemingly involuntary as a result of overlearning through repeated use. The most common 12 irrational beliefs are shown in Exhibit 3.1.

Figure 3.1

Ellis’s (1957) ABC model.

Ellis’s Irrational Beliefs

1. The idea that it is a dire necessity for adults to be loved by significant others for almost everything they do—instead of concentrating on their own self-respect, on winning approval for practical purposes, and on loving rather than on being loved.

2. The idea that certain acts are awful or wicked and that people who perform such acts should be severely damned—instead of the idea that certain acts are self-defeating or antisocial and that people who perform such acts are behaving stupidly, ignorantly, or neurotically and would be better helped to change. People’s poor behavior does not make them rotten individuals.

3. The idea that it is horrible when things are not the way we like them to be—instead of the idea that it is too bad, that we would better try to change or control bad conditions so that they become more satisfactory, and if that is not possible, we had better temporarily accept and gracefully lump their existence.

4. The idea that human misery is invariably externally caused and is forced on us by outside people and events—instead of the idea that neurosis is largely caused by the view that we take of unfortunate conditions.

5. The idea that if something is or may be dangerous or fearsome, we should be terribly upset and endlessly obsess about it—instead of the idea that one would better frankly face it and render it nondangerous and, when that is not possible, accept the inevitable.

6. The idea that it is easier to avoid than to face life difficulties and self-responsibilities—instead of the idea that the so-called easy way is usually much harder in the long run.

7. The idea that we absolutely need something other or stronger or greater than ourselves on which to rely—instead of the idea that it is better to take the risks of thinking and acting less dependently.

8. The idea that we should be thoroughly competent, intelligent, and achieving in all possible respects—instead of the idea that we would better do rather than always need to do well and accept ourselves as imperfect creatures, who have general human limitations and specific fallibilities.

9. The idea that because something once strongly affected our lives, it should indefinitely affect it—instead of the idea that we can learn from our past experiences but not be overly attached to or prejudiced by them.

10. The idea that we must have certain and perfect control over things—instead of the idea that the world is full of probability and chance and that we can still enjoy life despite this.

11. The idea that human happiness can be achieved by inertia and inaction—instead of the idea that we tend to be happiest when we are vitally absorbed in creative pursuits or when we are devoting ourselves to people or projects outside ourselves.

12. The idea that we have virtually no control over our emotions and that we cannot help feeling disturbed about things—instead of the idea that we have real control over our destructive emotions if we choose to work at changing the musturbatory hypotheses we often use to create them.

Beck and Cognitive Therapy

Beck (1976) similarly posited that much of emotional distress is due to problematic and inflexible ways of thinking. Consequently, even if individuals elicited positive reinforcement from their environment, cognitive biases would prevent them from benefiting emotionally from the reinforcement.2 Also, negative beliefs are hypothesized to interfere with behaviors that would otherwise elicit positive reinforcement or produce behaviors that lead to negative consequences. This is most evident in depression, where, for example, negative thoughts about the self may lead to negative self-talk in interactions with others. Such negative self-talk may be experienced as aversive by others, who therefore avoid the speaker in the future. The resultant social isolation then contributes to further depression, but it is important to note, the isolation is generated in the first place by negative thinking. Negative beliefs are hypothesized to derive from genetic predispositions, modeling of cognitive style by primary care givers, and adverse life events.

Also, negative thoughts are believed to remain dormant until activated by negative mood states or stressful life events, particularly those that match the content of the negative beliefs. Beck’s approach has evolved considerably over time. Indeed, one of the criticisms has been its changing nature, in that terms are replaced by new terms or the same terms are used to reflect different concepts. In its more recent forms, the approach uses a computer-based model of information processing. As Beck (2005) himself noted,

Simply stated, the cognitive model of psychopathology stipulates that the processing of external events or internal stimuli is biased and therefore systematically distorts the individual’s construction of his or her experiences, leading to a variety of cognitive errors (e.g., overgeneralization, selective abstraction, and personalization). Underlying these distorted interpretations are dysfunctional beliefs incorporated into relatively enduring cognitive structures or schemas. When these schemas are activated by external events, drugs, or endocrine factors, they tend to bias the information processing and produce the typical cognitive content of a specific disorder. (p. 953)

D. A. Clark, Beck, and Alford (1999) outlined 11 basic assumptions of Beck’s cognitive information processing model:

1. The capacity to form cognitive representations of the self and the environment is central to human adaptation and survival. Other terms used interchangeably with cognitive representations are meaning structures and schemas (the latter term is used herein). A schema is conceptualized as an internal model of the self and the world that is used to perceive, code, and recall information. Schemas are adaptive to the degree that they facilitate the processing of the extensive amount of information we encounter in daily life. However, as social and cognitive psychologists have noted for some time, the need for efficiency results in natural biases toward encoding and retrieving information that is consistent with a schema at the cost of information that is inconsistent. Such biases are believed to contribute to the persistence of schemas over time.

2. Human information processing is presumed to occur at different levels of consciousness extending from the preconscious, unintentional automatic level to the highly effortful, elaborative conscious level. In cognitive therapy, conscious appraisals are viewed as a valid data point.

3. A basic function of information processing is the personal construction of reality, as represented in schemas, but in contrast to constructivism, which denies an objective reality, Beck’s cognitive theory and therapy subscribes to a dual existence involving both an objective reality and a personal, subjective phenomenological reality.

4. Information processing serves as a guiding principle for the emotional, behavioral, and physiological components of human experience. Also, each affective state and psychological disorder has its own specific cognitive profile (i.e., cognitive content specificity), and the cognitive content determines the type of emotional experience or psychological disturbance that is experienced. Thus, depression and sadness involve appraisals of loss or failure, happiness involves thoughts of personal gain, anxiety and fear involve evaluations of threats or danger, and anger involves appraisals of assault or transgression on one’s personal domain. Furthermore, some schemas are core in that they are related to the basic sense of identity or self, whereas others are peripheral. The core schema in depression, for example, pertains to self-worth as defined by either interpersonal relations (sociotropy) or autonomous achievement (autonomy); sociotropic individuals would be more likely to become depressed in interpersonal rejection situations, whereas personal achievement stressors would be more relevant to individuals high on autonomy. Core schemas are heavily influenced not only by distortions in information processing and lack of attention to information that has disconfirmatory power but also by behaviors that confirm the schemas. As an example, the behavior for someone whose schema is of being unlovable may take the form of neediness, and such neediness may alienate others, which in turn confirms the schema of being unlovable.

5. Cognitive functioning consists of a continuous interaction between lower order, stimulus driven processes and higher order semantic processes. These are referred to as top–down and bottom–up processes. Information processing is seen as the product of higher order, top–down processing, involving abstraction and selection, and the more basic, bottom–up processing of raw stimulus characteristics in the environment. In nonpathological states, appraisals are evenly influenced by the bottom–up situational context (i.e., empirical data), as well as by top–down, higher order inferences. Psychopathology is caused by information relevant to the disorder becoming hyperaccessible due to dominant maladaptive schemas. These schemas result in heavy top–down influences of selection, abstraction, and elaboration of information. Hence, the dysfunctional schemas are likely to lead to dysfunctional automatic thoughts, or surface level cognitions. These thoughts are called automatic because they are often fleeting and unnoticed and are not necessarily fully conscious. Beck presumed that these appraisals led directly to situationally specific emotional and behavioral responses. Hence, a schema of being unlovable may lead an individual to appraise his partner’s behavior as a sign of disinterest—when in fact the partner is preoccupied with her own concerns—leading the individual to feel sad and to become more withdrawn.

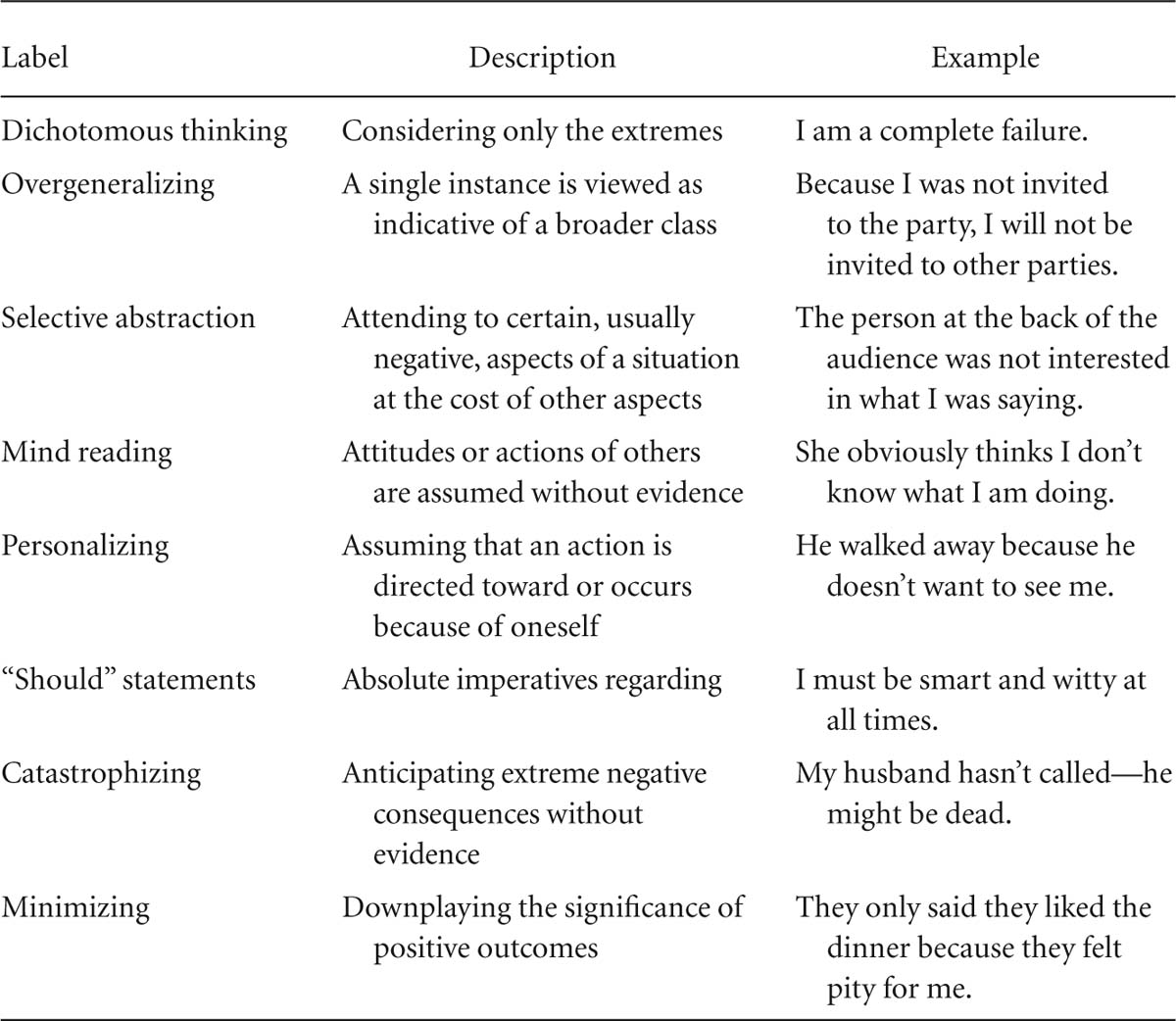

Such automatic situational appraisals are mediated by cognitive distortions in information processing. Cognitive distortions provide a bridge between automatic thoughts and schemas. That is, cognitive distortions of new or ambiguous information tend to be driven by schemas and then lead to automatic thoughts becoming accessible in consciousness. Examples of such distortions are shown in Table 3.1.

6. Schemas are at best an approximation of experience, in that all information processing is egocentric and therefore a biased representation of reality. What distinguishes cognition between disordered and nondisordered states is the degree to which the former is influenced by prepotent dysfunctional schemas.

7. Schemas develop through repeated interactions between the environment and innate rudimentary schemas. That is, they develop by increasing elaboration and connections with other schemas, and those schemas that are activated more frequently become more elaborated and therefore more dominant in the overall organization of schemas. For example, the more often the schema of being unlovable is activated, the more likely the concept of being unlovable will dominate interpretations of ongoing situations. Furthermore, schema development is additionally influenced by genetic or biological propensities.

8. Schemas are organized in different levels. The most basic level is single schemas. Single schemas then cluster together to form nodes, or the cognitive representation of psychological disorders. Nodes then interconnect with other nodes as the cognitive representation of personality.

9. Schemas are characterized by different levels of threshold activation, which occurs through a match between stimulus features of the environment and relevant schemas. Schemas that are more frequently activated have lower thresholds for activation and thereby are hypervalent and more dominant. Dominant schemas become activated by a wide array of environmental stimuli and trivial matching stimuli; they are easily accessible, dominate information processing once activated, and resist deactivation.

10. Two general orientations are represented, the first aimed at the primary goals of the organism (or schemas involved in meeting the basic needs necessary for survival) and the second aimed at secondary constructive goals (or schemas to do with preservation, reproduction, dominance, and sociability). Most primal processing occurs at automatic or preconscious levels and tends to be rigid and inflexible, whereas processing at the secondary level is more conscious and controlled. In psychological disorders, the primary schemas have become more dominant and the constructive schemas less active.

11. Psychological disturbance is usually characterized by excessive activation of specific primal schemas that lead to narrowing of information processing and inadequate activation of other more adaptive schemas.

Cognitive Appraisal Theory and Expectancy-Learning Theory

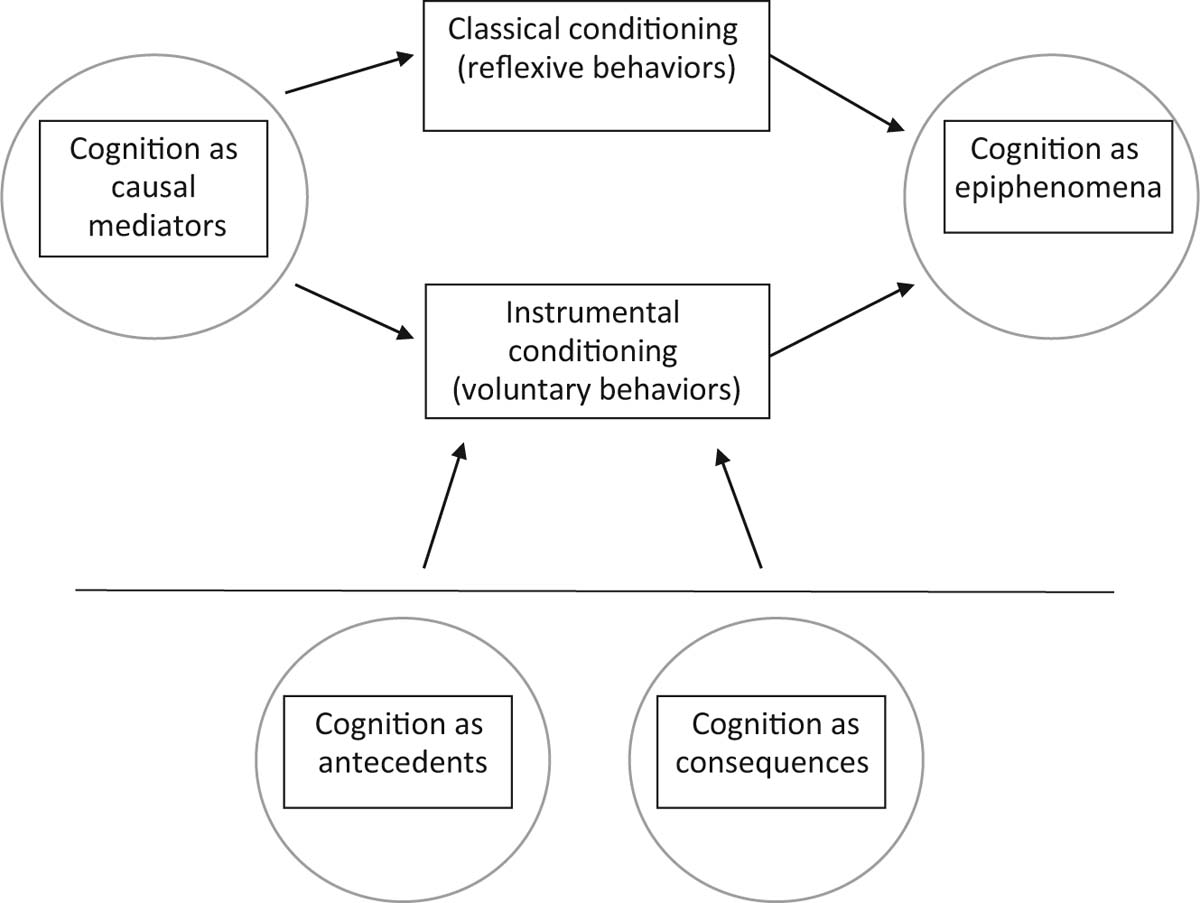

As reviewed, classical and instrumental conditioning models incorporate cognition in the form of outcome expectancies for the likelihood and valence of the US and of consequences, respectively, with ongoing debate as to the necessity for expectancies to be explicit, conscious appraisals versus implicit, automatic representations. In contrast, cognitive appraisal theory is essentially about the content of cognitions at the level of explicit, conscious appraisals.3 These theories can be intertwined in a number of ways, including the contribution of instrumental and classical conditioning to the development of conscious appraisals. For example, persons who have been traumatized (i.e., classical aversive conditioning) are likely to develop beliefs about the world as being a dangerous place, and persons who are not positively reinforced for their efforts may develop negative beliefs about themselves or the world.

In this way, cognitions can be considered the epiphenomena of conditioning. Once acquired, these cognitions may then feed back to influence subsequent learning experiences by influencing expectancies for US or for consequences. Thus, a belief that the world is a dangerous place may become a causal mediator in future learning experiences, because the belief increases the expectancy of aversive events. For example, following criticism from a peer, expectancies for more and greater criticism are likely to increase the chances of becoming conditionally fearful as a result of negative social interactions in the future. Similarly, a negative belief about oneself, which developed out of lack of positive reinforcement, may become a causal mediator by contributing to the devaluation of future reinforcers, thereby leading to further loss of positive reinforcement. These interrelations are depicted in Figure 3.2. Note that this figure does not include two important issues: the myriad of other sociocultural and biological factors, aside from conditioning, that contribute to beliefs and the aspects of classical and instrumental conditioning that may occur without conscious cognitive mediation (see Kirsch et al., 2004).

The primary assumption of cognitive therapy, whether in accordance with Ellis or Beck, is that dysfunctional thinking can be changed and, in turn, lead to symptomatic relief and improvement in functioning. Ellis (2003) noted that

being constructivists (both innately and by social learning), and having language to help them, they are also able to think about their thinking, and even think about thinking about their thinking. Therefore, they can therapeutically choose to change their IBs [irrational beliefs] to more rational (self-helping) beliefs. (p. 80)

Figure 3.2

Cognitions and instrumental and classical conditioning.

A key concept is the development of alternative cognitive content that is more realistic and evidence-based and less governed by core irrational beliefs or schemas. Hence, the focus is on changing the content of beliefs, automatic thoughts, and assumptions. As D. A. Clark et al. (1999) noted:

The degree of symptomatic improvement brought about by these interventions will depend on the extent of change produced in the information processing system. Moreover, recovery will be more enduring and relapse reduced if the underlying maladaptive meaning-structures, and not just negative thinking, are targeted for change during treatment. (p. 70)

Conscious reasoning is used to change the content of beliefs. According to Beck and Clark (1997), “One of the most effective ways of deactivating the primal threat mode is to counter it with more elaborative, strategic processing of information resulting from the activation of the constructive, reflective modes of thinking” (p. 55). Cognitive therapy represents such elaborative, strategic processing. Thus, cognitive therapy functions at the conscious level to effect changes in the preconscious level.

However, the mechanism by which primal automatic thoughts are changed by more elaborative strategic thoughts is not well understood, and several models exist (Garratt, Ingram, Rand, & Sawalani, 2007). The accommodation model assumes that the content of underlying schemas is changed in profound ways. Another model, known as the activation–deactivation model, suggests that the schemas remain intact but become deactivated over the course of treatment. In a third model, schemas may remain unchanged, but new schemas develop as a result of therapy and these schemas incorporate skills for dealing with stressful situations (Garratt et al., 2007). However, the data on mechanisms are sparse (as described in more detail in a following section), and the precise mechanisms through which beliefs change remain unclear.

Another concept key to cognitive therapy is an empiricist approach. This involves incorporating more bottom–up processes rather than being predominantly driven by inferences or top–down processes that are guided by maladaptive schemas or illogical thinking. An empiricist approach also involves developing an awareness of one’s own thinking and learning to distance, or view one’s thoughts more objectively and draw a distinction between “I believe” (an option that is open to discontinuation) and “I know” (an irrefutable fact). Skills are taught not only for how to identify distortions in thinking but also for how to categorize and distance from negative thoughts and how to develop more evidence-based and constructive thinking. Behavioral experimentation is used to gather evidence for the formation of more constructive thinking. These skills are then used whenever negative emotions or dysfunctional behaviors are expressed. Hence, the skills provide a coping tool that is intended to remain in place and even strengthen after formal treatment is over. Cognitive therapy does not aim to teach accuracy in appraisals. Rather “the more relevant question is whether the person is able to conceptualize the situation in a manner that will facilitate mastery or coping” (D. A. Clark et al., 1999, p. 64). Learning to have flexibility in thinking and the ability to take multiple perspectives rather than a single narrow interpretation is a way of facilitating mastery and coping.

In sum, the fundamental process of cognitive therapy is to extract information from the environment that activates different ways of thinking. In Beck’s model in particular (Beck & Clark, 1997), this information is intended to compete with dysfunctional schemas or generate compensatory schemas that deactivate dysfunctional hypervalent schemas. Information is obtained in a number of ways, including logical discussion of the evidence, disputation, and behavioral experimentation to gather evidence.

Cognitive–Behavioral Theory

Cognitive–behavioral theories of psychopathology and psychotherapy draw on learning theory as well as cognitive theory principles described thus far: CRs for innately aversive or appetitive events and the role of expectancies in the generation of those responses; instrumental learning from the consequences of responding and the role of expectancies on that learning; reciprocal determinism among cognitions, behaviors, and the environment from social learning theory; and the content of cognitive appraisals. Conceptually, these are intertwined, with behavioral experience molding cognitions and cognitions molding behavioral experience in a continuous, reciprocating fashion. As previously described, cognition can be regarded as a product and as a mediator of instrumental and classical learning, and learning can be regarded as a contributor to conscious cognition. Consequently, treatment is guided by the influence of learning experiences on cognition and the influence of cognition on learning experiences.

In the cognitive–behavioral model of posttraumatic stress disorder, for example, the initial traumatic event is assumed to establish classically conditioned fear reactions to reminders of the trauma. In addition, the effects of the trauma, including the extent of the conditional responding, are assumed to be enhanced by catastrophic appraisals about the meaning of the trauma with regard to oneself (e.g., “I am weak”) and the world (“The world is full of danger”). Together, these processes lead to avoidance behavior, which in turn is reinforced by the reduction in distress it produces, and which also perpetuates conditional fear (because avoidance interrupts extinction) and catastrophic appraisals.

Similarly, in the cognitive–behavioral model of substance use disorders, antecedents to drug use behavior are assumed to be established through repeated pairings with positive or negative reinforcement or through the anticipation of reinforcement. Cognitions, such as expectancies about the reinforcing value of the drug effects, and emotions, such as distress or anger, are presumed to mediate the antecedents and subsequent drug use behavior. Furthermore, drug use behavior is presumed to be maintained by its consequences, be it decreased craving or decreased withdrawal symptoms, decreases in negative affect or increases in positive affect, or decreased focus on other problems and concerns. Also, negative beliefs about the self or the world may contribute to the negative affect from which the drug serves as an escape.

In the cognitive–behavioral model of depression, emphasis is given to the lack of positive reinforcement derived from the environment, some of which may be attributed to independent factors over which the individual has no control and others that are likely to derive from the individual’s own actions. An example of the latter is interpersonal conflict and isolation that occurs in part as a result of the individual’s own depressive interpersonal style. The latter behaviors are themselves likely to be influenced by negative appraisals of oneself or the world, and their consequences serve to only reinforce the negative appraisals in a reciprocating style. Negative appraisals themselves also are likely to devalue the reinforcers that are received from the environment.

In one more example, the cognitive–behavioral model of chronic pain recognizes the role of conditional pain behaviors to reminders of pain (e.g., a doctor’s office), the role of reinforcement in the maintenance of pain behavior (e.g., attention from significant others, escape from unpleasant tasks or duties), and the effects of cognitive appraisals on the perceived intensity and unmanageability of pain, which in turn are likely to magnify CRs and the reinforcement of pain behavior.

Clinicians vary in the emphasis given to cognitive versus behavioral principles. This variation influences subtleties in the ways in which cognitive and behavioral intervention strategies are implemented. For example, a more behaviorally oriented clinician will view exposure therapy to feared situations as a primary vehicle for extinction of CRs. A clinician with a social learning theory orientation will view exposure therapy as a performance accomplishment that raises self-efficacy. A more cognitively oriented clinician will view exposure therapy as a vehicle for obtaining information that disconfirms misappraisals.

1Genetic endowments and temperament are viewed as additional contributing factors to problem behaviors, cognitions, and emotions.

2Noteworthy is the overlap between cognitive theory and expectancy-based models of instrumental learning.

3Beck’s model recognizes the role of subconscious cognitive processes, but the immediate target of cognitive therapy is conscious cognitive appraisals.