NEW YEAR’S DAY 1946 represented more than the usual festive celebrations that mark the transition of one year to the next. For the first time in seven years there was neither war nor the threat of war on the horizon, and now something other than military campaigns might capture the public’s attention. A nation that had just steered through the treacherous shoals of a global conflict now found itself free to look farther back and farther forward for inspiration. One of the first news stories of 1946 was the 81st annual encampment of 67 Union Army veterans in Cleveland, where 102-year-old Robert Ripley of New York was elected commander-in-chief with a mandate to invite Confederate veterans to a joint reunion that summer.

Despite the eight decades that separated the American Civil War from the 1940s, tangible links to the conflict remained. During their childhoods, many of the returning World War II veterans had met Civil War participants. The wife of Gen. James Longstreet, Robert E. Lee’s deputy at Gettysburg, was photographed riding in the back of a convertible at an Independence Day celebration, and Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, commander of American forces in the battle of Okinawa and the most senior general to die in combat, was the son of Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, Sr., one of Ulysses S. Grant’s closest friends at West Point and the first Confederate commander to surrender to the future Union commanding general. Older men and women still regaled wide-eyed children with stories of glimpses of Abraham Lincoln or Jefferson Davis, or even early memories of life as a slave.

Yet if America was still tethered to links with the Civil War era and nostalgic aspects of nineteenth-century life, an equally powerful attraction was the world of the twenty-first century that lay just over the horizon. The January 1946 issue of a national news magazine followed an article on Civil War veterans with a feature on the “Great Electro Mechanical Brain,” describing MIT’s follow-up to the University of Pennsylvania’s breakthrough ENIAC “differential analyzer,” with its computing machine that “advances science by freeing it from the pick and shovel work of mathematics.” The new mechanical brain in Cambridge, Massachusetts, used two thousand vacuum tubes and two hundred miles of electrical wire in one hundred tons of hardware and metal that could solve in thirty minutes a problem that would take human scientists more than ten hours to complete. The four members of ENIAC’s technical crew fed data to the machine that “could advance the frontiers of knowledge by liberating scientists from everyday equations for more creative work.”

The exciting world of the “Atomic Age” future was a feature of current advertising. An early 1946 ad for the Hotel Pennsylvania illustrates the New York City of the twenty-first century with futuristic helicopters landing businessmen on the hotel roof. The copy insists that “many things are sure to change our lives in the new era of a new century. However, whether you come by helicopter or jet car, the Hotel Pennsylvania will never serve concentrated food pills as even in the future, we will still have full and robust meals.”

Somewhere between the quaintness of the gaslight era and the excitement of the looming 21st century stood a real world into which 76 million babies would be born over the next 18 years. This America held tantalizing glimpses of the society we know today yet had been shaped substantially by the war and the depression decade of the 1930s. Compared to the fashion standards of twenty-first-century society, for example, most midcentury men, women, and to some extent children dressed much more formally, with propriety often trumping comfort.

The young men who would become the fathers of Boomer children included a large percentage for whom dress shirts, dress shoes, neckties, coats, and even dress hats were required wear—from work to PTA meetings to religious worship and even to summer promenades on resort boardwalks and piers. Men who worked in strenuous jobs, on assembly lines and loading docks, might be seen wearing neckties under their coveralls; and for individuals employed in corporate offices, banks, and department stores, removing a coat on a hot summer day was an act of major informality. When most male white-collar workers ventured outside, they usually wore a wide-brimmed fedora that looked very much like the headwear of most other men, with the exception of a few seniors who refused to relinquish their old-fashioned derbies or straw skimmers. Men’s hairstyles were almost as standardized as their clothes, the main variation being a choice between maintaining the close-cropped “combat cut” that had been required in the military service or returning to the longer prewar slicked-back hair held in place by large amounts of hair tonic or cream.

These young men were now pairing off with young women who in some ways looked dramatically different from their mothers and were entering a period where comfort and formality were locked in conflict. Relatively recent women’s fashions had undergone far more seismic changes than men’s styles. In relatively rapid succession, the piled-up hair and long dresses of the Titanic era had given way to the short-skirted Flapper look of the 1920s, which in turn had morphed into the plucked eyebrows, bleached hair, and longer skirts of the depression era.

By the eve of Pearl Harbor, all of these looks seemed hopelessly old-fashioned to teenagers, college girls, and young women, and the war brought still more change. Fashion for immediate postwar females in their teens or twenties featured relatively long hair, bright red lipstick, fairly short skirts, and a seemingly infinite variety of sweaters. The practicality of pants for women in wartime factories had led to a peacetime influx of slacks, pedal pushers, and even shorts, matched with bobby sox, knee socks, saddle shoes, and loafers. While skirts or dresses topped by dressy hats and gloves were still the norm for offices, shopping, and most social occasions, home wear and informal activities were becoming increasingly casual, especially for younger women.

The preschool and elementary school children of the immediate postwar period, many of whom would later become the older siblings of the Boomers, appear in most films, advertisements, and photos to be a fusion of the prewar era and the looming 1950s. Among the most notable fashion changes for boys was a new freedom from the decades-long curse of knickers and long stockings that had separated boyhood from adolescence and produced more than a few screaming episodes of frustration as boys or their mothers tried to attach often droopy socks with tight, uncomfortable knicker pants. As prewar boys’ suspenders rapidly gave way to belts, the classic prewar “newsboy” caps were being replaced by baseball caps.

Girls who would become the older sisters of the postwar generation were also caught in a bit of a fashion tug-of-war. An informal “tomboy” look of overalls, jeans, and pigtails collided with the Mary Jane dresses and bangs of the prewar era in young mothers’ versions of their daughters.

The tension between past and future in American fashion was equally evident in many aspects of everyday life into which the new, postwar babies would arrive. For example, one of the first shocks that a young visitor from the twenty-first century would receive if traveling to the early postwar period would be the haze of tobacco smoke permeating almost every scene. The Boomers may have been the first generation to include substantial numbers adamantly opposed to smoking, but most of their parents and grandparents had other ideas. Nearly two of three adult males used pipes, cigars, or cigarettes, and almost two of five women were also regular smokers in the early postwar era. This was a world in which early television commercials and great numbers of full-color magazine advertisements displayed a stunningly handsome actor or a beautiful actress elegantly smoking a favorite brand of cigarette while a doctor in a white coat and stethoscope explained the ability of one brand of cigarette to keep the “T zone” free of irritation. Other doctors intoned that serious weight-watchers should “reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.” One series of magazine ads noted that in a survey of 113,597 physicians, “more doctors smoke Camels than any other brand.” Even in the minority of homes where neither parent smoked, ashtrays were always readily available for the many relatives and friends who did use tobacco, thus ensuring that few Boomers would grow up in truly smoke-free homes.

The same young visitor from the twenty-first century who would be astonished at widespread tobacco use by the parents and grandparents of Boomers would find their eating habits equally cavalier. One of the most common scenes in films from the 1930s or the World War II era was a group of civilians or soldiers gathered around a fire or a foxhole dreaming of the “perfect” meal they would enjoy when the depression or the war ended. The dream fare always included steaks, bacon, a cornucopia of fried foods, and desserts, topped off with a good smoke. In an era when the real hunger of the depression and the shortages of the battlefield were still fresh memories, the prosperity of the late 1940s offered the possibility of meals where cardiovascular concerns made little difference.

The idea of a balanced diet was far from alien to the young women who would become the mothers of postwar babies. Yet this was a society in which frozen food was still a novelty, and for many families the term “icebox” continued to be a literal description of home refrigeration. Menus were still based on the seasonal availability of foods, and their ability to be “filling” continued to be emphasized. Shopping for many families was a daily excursion, and while early Boomer children would eventually be introduced to the world of gleaming supermarkets and shopping centers, a substantial part of selecting food, buying it, and preparing it was still clearly connected to earlier decades.

Along with fashion and everyday culture, another aspect of early postwar life that was caught between past and future was popular entertainment. American families living in the time immediately after World War II essentially relied on the same two major entertainment media that had dominated the preceding two decades: motion pictures and radio. A movie ticket might cost 25 to 35 cents for an adult and 10 to 15 cents for children. The first full year of peace produced the highest movie attendance in history and the release of five hundred new films. Most of them were relatively similar to their counterparts in the “golden age” of the 1930s—primarily black-and-white features of comedy, drama, romance, Westerns, or war, and dominated by a “superstar” tier of Olympian actors and actresses. Cary Grant, Errol Flynn, Gary Cooper, Humphrey Bogart, and Clark Gable commanded the most attention and money among early postwar actors; Paulette Goddard, Betty Grable, Claudette Colbert, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jane Wyman were the queens of the silver screen. A few changes could be detected when compared to the movies of the mid-1930s: the number of color films was slowly increasing, the recently ended war was still being fought on screen, and the challenge of returning to civilian life was being explored in productions like The Best Years of Our Lives. Some Westerns dealt with more complex social issues and a more realistic and sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans, as in Fort Apache.

On evenings when an excursion to the neighborhood movie theater was not planned, families gathered in their living rooms and tuned in to radio stations that supplied children’s programs, classical concerts, situation comedies, mysteries, and popular music, in roughly half-hour portions. Radio was free, was accessible, and allowed varied levels of engagement, from intense concentration to background noise. It would continue to be an important if diminishing element in the awareness of the older portion of the Boomer cohort. Yet this generation was almost immediately labeled the “television generation,” and there are good reasons why this identification is largely accurate.

The development of commercial television coincided almost perfectly with the beginning of the postwar surge in births. By late 1946 four television stations were on the air in the United States, with an audience of several thousand, but the possibility of geometric growth was already being discussed. A year later one magazine noted that “television is a commercial reality but not yet an art.” The author explained, “Today more people want to buy sets than there are sets to buy; the television audience has soared from 53,000 sets in 1940 to one million today. After a twenty-year infancy, television is beginning to grow up. Neither the movies, nor radio, nor theater, nor any of the arts has yet developed a technique suitable to this revolutionary new medium whose possibilities, once they are recognized, will be limitless.”

While the nation’s 122,000 operating television sets were overwhelmingly outnumbered by 65 million radios, 2 million TVs were projected by the end of 1949. The seventeen existing television channels in late 1947 offered a variety of new experiences for viewers. American audiences were now able to witness some “breathtaking scenes. They saw and heard the United Nations and the President of the United States. As if personally in Westminster Abbey, they witnessed the marriage of a future Queen of England, televised only 29 hours after the ceremony, from newsreels flown across the ocean.” Yet television also bombarded its growing audience with “some of the worst aspects of radio: implausible drama, sword swallowers, and witless chit-chat.”

Fewer than ten months after this complaint appeared, another magazine explained why the new medium was changing the face of family entertainment. “Television is catching on with a speed that has amazed its own developers. It promises entertainment and advertising changes that frighten radio, movies, stage and sports industries. The 100,000 sets now in use will quadruple next year, the 38 stations will be 123 by next summer. A New York station last week announced a 7:00 A.M. to 11:00 P.M. program five days a week.” Even these enormously optimistic reports could not anticipate the consequences to the new generation of children—within ten years 19 of every 20 households would own a television that would become teacher, baby-sitter, and seductress all in one.

The young men and women who would soon deal with television’s siren song to their children were mainly keeping marriage license offices, obstetricians, and home builders busy in their mass transition from singlehood to parenthood. The parents of the Boomers were blazing new trails, not only in creating a surge in the birthrate but in the entire minuet that constituted courtship and marriage. Parents of Boomers had grown up in a society where marriage almost always seemed to be more acceptable than permanent bachelorhood or spinster status. A combination of the number of deaths caused by World War I and the subsequent influenza pandemic, the social dislocation of the “Roaring Twenties,” and the economic depression of the thirties had left nearly one-fourth of eligible young people permanently single and many others entering less than optimal marriages in order to avoid this outcome. Then World War II and its aftermath seemed to change the rules. The global conflict shuffled the matchmaking deck in a variety of ways that created complex new relationships while sending the marriage rate soaring to new heights.

In the wake of World War II, a substantial number of postwar newlyweds had never even met before Pearl Harbor. Eligibility and attraction had been reshuffled as if by some mischievous Cupid. A young Chicago soldier who had never been south of Joliet might suddenly find himself hopelessly smitten by a Georgia girl who grew up near his base at Fort Benning. A girl from central New York, who had narrowed her potential partners to the two or three eligible boys in her town, now might find herself working at an army air corps base filled with ten thousand eligible young men and realize that a college professor from Philadelphia or a physician from Baltimore offered not only a convertible and the top dance bands at the officers’ club but a whole new married adventure in a big-city suburb.

The war encouraged marriage between Northerners and Southerners, Protestants and Catholics, Americans and foreigners. The Pacific theater offered opportunities for servicemen and at least some servicewomen to discover their partners in Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, China, and even occupied Japan. But the European theater offered far more possibilities for romantic matches. American soldiers engaged in more than a few encounters that left behind a devastated young woman or a child of mixed nationality with no legal father; but thousands of more permanent relationships developed between Yanks and European women, notably in Great Britain. One news magazine devoted a lengthy article to the arrival of one of the first “war bride” ships that sailed from England to New York after the war, carrying hundreds of foreign brides. The reunion on the docks produced a wide spectrum of emotions as some mothers with small babies introduced child and father, some men and women did not recognize their spouses, and some individually or mutually decided that the other person was not for them.

The many interregional and international relationships that did succeed produced a new generation of children who in some respects were the least parochial Americans in history. Suntanned children living in their father’s Los Angeles home town found themselves slightly alien visitors among their pale cousins in their mother’s birthplace of Buffalo or Rochester. Some children of war brides found themselves spending Christmas (and Boxing Day) with their British grandparents or their non-English-speaking French or Italian cousins.

As spousal preferences, employment or educational opportunities, or just a sense of adventure propelled young married couples to particular communities, a new generation of young Americans began arriving. For nearly two decades, economic disorders and war had kept birthrates at low levels. Now the combination of peace, prosperity, and a sense of new beginnings created an almost magical environment in which not just one or two children but three, four, or more became a goal for the generation of postwar parents. These young men and women were making decisions for marriage and children in a culture that largely congratulated them for their choices. Newspaper articles and magazine advertisements asked the seemingly rhetorical question, “Are Married People Happier?” and answered, “Yes, it is true that husbands and wives, particularly fathers and mothers, are happier; nationwide surveys have found that the majority of men and women agree—marriage is surely essential for happiness.” While periodicals carried series on “making marriage work,” or “the exciting experience of pregnancy,” advertisements hinted that singles were somehow missing out.

A colorful ad for the Armstrong Cork Company in a trade magazine insisted that the addition of its new child-friendly tile floors in department stores would be the foundation of “new ideas for children’s shops of the future,” for catering to mothers and mothers-to-be was becoming a big business and “smart merchandizing is making it even bigger.” A spacious, linoleum-floored department showed a large infant-needs area set off from the rest of the store, furnished with soft upholstered chairs to offer expectant mothers and young mothers comfort and privacy while they selected layettes. An adjacent merry-go-round display of soft toy animals “makes them accessible for impulse buying,” and roomy playpens “are a comfortable, safe spot to leave a child” while registering for the next baby shower, which signaled the imminent arrival of a younger brother or sister.

There has never been a period in American history when society has not supported the production of a new generation to continue the nation’s cultural heritage. But the early post–World War II era provided a particularly vigorous public and private encouragement of marriage and child-rearing seldom duplicated. Much of this stimulus emerged late in the war when, as much as the nation prayed for peace, it feared that victory and the resumption of normal life might throw the United States back into what for many Americans was the even more terrifying experience of the Great Depression.

As the war neared an end, the New Republic predicted, “When Demobilization Day comes we are going to suffer another Pearl Harbor perfectly foreseeable—now—a Pearl Harbor of peace, not war.” Political commentator Max Lerner insisted that once the economic stimulus created by the war ended, “the unemployment rate would be one of the most serious in American history.” A Gallup poll in 1944 found that half of all of those interviewed estimated that the unemployment rate would surge to between 15 and 35 percent when peace returned; the Labor Department estimated a 21 to 27 percent range. Soldiers interviewed in a government survey thought by a 2-to-1 margin that the depression would return. One of the most surprising aspects of these surveys was that their pessimistic projections were forecast during a period of unparalleled prosperity. As World War II reached its climax, unemployment in the United States dropped to 1.9 percent, the lowest in history, yet this good fortune seemed tied mainly to the demands of the conflict still raging.

The most feasible antidote to a grim future seemed to be to get women war workers back to being full-time housewives and mothers while some returning veterans filled their jobs and others returned to school to gain credentials for better jobs. The key to this complex maneuver of role switching was to convince the Rosie the Riveter generation to trade their jobs for aprons and baby bottles, thus producing employment or educational opportunity for their new husbands and new homes for the families that would hopefully follow. The main engines for this social revolution proved to be an innocuous-sounding piece of legislation called the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act and an unpretentiously titled book, Baby and Child Care, by Benjamin Spock, M.D. Each of these documents empowered young couples to believe they could create households and families surpassing any past generation in comfort, caring, and security for their children.

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act was passed in September 1944 and was quickly shortened for everyday use to the “G.I. Bill.” More than 15 million servicemen and women were eligible for educational benefits under the bill, including full tuition to an educational institution of the veteran’s choice, a $35 monthly stipend for single students, $90 a month for married veterans, and up to $120 a month for students with children.

This sliding scale influenced the creation of postwar families by prompting a rearrangement of the traditional school, marriage, family continuum. Now many marriages and births would occur parallel to college study. Hundreds of postwar campuses featured married and family housing, ranging from surplus Quonset huts and converted military barracks to more comfortable apartment houses. Mostly male veterans would emerge each morning from these “Vets-villes” or “Fertile Acres” to confront Philosophy or Business Law while their young wives dealt with the challenge of child-rearing on the cheap. At the University of Minnesota’s Veterans Village by 1948 there were 936 new babies and even more toddlers. The Village had a twelve-member board of aldermen made up of eleven young mothers and only one man. It decreed that any adult automatically became the temporary guardian of an unsupervised child, and initiated the right to spank any child who attempted to cross a dangerous street alone. Group shopping and baby-sitting were promoted, and the limited supply of home appliances was commonly shared by all.

Married students at Stanford University: the G.I. Bill not only strained classroom facilities in postwar colleges but also created a new, parallel collegiate culture in which fraternity parties gave way to baby-sitting, trips to the playground, and shopping excursions. (Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

As of April 1947, of 2,000 married veterans at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, 800 already had new babies, and 288 others had wives in first pregnancies. The university persuaded the state’s Public Housing Authority to send in hundreds of prefab buildings that had been used for war workers, which now clustered around a cooperative grocery store, a bowling alley, and a community recreation center.

The millions of married veterans and their spouses, who largely abandoned fried chicken for chicken soup and set up housekeeping in “homes” that had only recently served military purposes, faced a demanding experience that drove many young men and women to the limits of their endurance. Veterans attempted to study amid the din of screaming babies and noisy toddlers, not helped by paper-thin walls, while their wives set up housekeeping with few conveniences or appliances. Yet it seems likely that a substantial number of these young couples saw their young children as a symbol of their independence from older relatives and older lifestyles and believed they had embarked on a marvelous adventure in this new “Atomic Age.”

One of the developments that made this great new adventure more manageable for young married couples, whether they lived in Fertile Acres or in more traditional housing, was the publication in 1946 of Dr. Benjamin Spock’s Baby and Child Care, a paperback book that sold for 35 cents and was designed specifically for anxious young postwar parents. The book would go on to sell 30 million copies in 29 languages before the last Boomer was born, becoming the best-selling new title ever published in the United States to that time. Young mothers, from former war workers to future first lady Jacqueline Kennedy, were effusive in their praise of Dr. Spock’s reassuring, nonjudgmental approach, which explained that a simple combination of relaxation, persistence, and, above all, a sense of humor would solve most baby care issues, and that trust in one’s innate maternal and paternal instincts was an excellent first step in the parenting experience.

The book included space for birth statistics, records of checkups, parent questions for the doctor, and an infant’s height and weight chart, along with advice that parents should enjoy their babies yet accept that some level of frustration was normal in all parenting activities. Spock admitted that “Children keep parents from parties, trips, theaters, meetings, games and friends. The fact that you prefer children and wouldn’t trade places with a childless couple for anything doesn’t alter the fact that you still miss your freedom.” Yet the rewards from this lifestyle were almost limitless, according to Spock, for compared with “this creation, this visible immortality, pride in other worldly accomplishments is usually weak in comparison.” On the other hand, if sacrifice was healthy, the martyrdom of needless self-sacrifice was counterproductive: “parents will become so preoccupied and tense that they’re no fun for outsiders or for each other.”

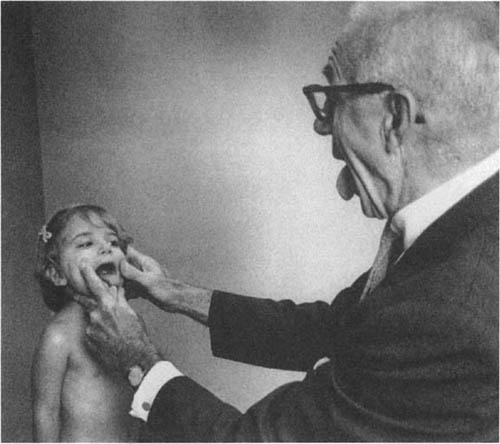

Dr. Benjamin Spock, above, emphasized a commonsense, relaxed approach to postwar child-rearing. His book on baby and child care became one of the best-selling books of modern times. (Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Benjamin Spock had the great good fortune to be accepted as authoritative and wise in a generally upbeat, pragmatic culture of young parenthood. His book gave young men and women permission to expand the traditional boundaries of parental involvement with and even indulgence in their children’s lives. These new parents were more willing to buy toys, less willing to use corporal punishment, and more open to friendship with their children than their own parents had been. New parenting now included playgroups, incentives for good behavior, and even children’s opinions in the forging of family decisions, from meals to vacations. New mothers were less often drill sergeants and more often counselors and advisers. New fathers were more involved and less forbidding.

When these young parents had a rare moment to consider their role in the chain of generations of mothers and fathers, they often sensed a certain uniqueness in their experience. First, it gradually became evident that more of them were having children, and the numbers of children were larger in an American society that until recently had seemed to be moving toward fewer and later marriages, and fewer children. Second, they were being assured in books, films, and political speeches that their experience was vital to the nation’s welfare and future prosperity. Third, they were aware that demographic and technological changes were rapidly redefining the kind of life they would live and where they would live it. If Benjamin Spock opened a new frontier in the experience of parenting, a fast-talking, chain-smoking former naval construction engineer opened a new portal on the kind of home life where many of them would raise these new families. William Levitt’s transformation of a vast expanse of Long Island potato fields into a planned, child-friendly suburban community would inaugurate a new family experience for the Baby Boomers and their young parents.