ONE OF THE MOST endearing films of the immediate postwar era gained much of its box-office popularity by recounting a modern fairy tale in which the prize is not a throne or riches but a “castle” in a new form of community that would come to define a newly emerging American lifestyle. Miracle on 34th Street is a story of the hopes and dreams of a little girl, played by Natalie Wood, living in a Manhattan apartment with her single mother, a Macy’s employee played by Maureen O’Hara. Cautioned by her mother to be skeptical of belief in Santa Claus, the little girl is coaxed into revealing her one true wish by a department store Santa who calls himself Kris Kringle. Dolls, toys, and cycles hold little interest for a girl who dreams of escaping the restrictions of apartment life for a new home in the suburbs, preferably with a new father who will complete a traditional family. When Kringle (Edmund Gwenn) is fired as Macy’s Santa and nearly committed to a mental hospital, a young bachelor lawyer played by John Payne choreographs a brilliant defense that acquits his client and sparks the beginning of a romantic interest with the single mother. As mother, daughter, and bachelor drive home from a suburban Christmas morning celebration, Natalie Wood orders Payne to stop the car and runs across a lawn into her “dream home,” which is empty and for sale. Payne and O’Hara run after her and discover their love for each other in an empty living room that holds only the cane used by Kris Kringle. The “miracle” is an escape from Thirty-fourth Street and a new beginning in a new family and a suburban home.

While few early postwar families could match the miraculous nature of this transition from urban crowding to a spacious suburban home, the film struck a major chord in the desire for young parents to establish themselves in a new frontier of lawns, picture windows, and barbeque pits—a lifestyle that seemed especially congenial to growing families of the new Baby Boom.

Postwar suburban development had its antecedents in the rise of earlier “bedroom communities” adjacent to large cities. Earlier in the twentieth century, the emergence of railroads, trolley cars, and other forms of public transportation had allowed workers in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and other cities to commute from suburban homes to downtown jobs. The depression and World War II, however, had brought suburban home construction nearly to a halt. Even in a more positive economic environment, early suburbs had often been tethered to rail lines, and huge swaths of land beyond the range of public transportation remained underutilized. Then, just as the G.I. Bill expanded veterans’ educational frontiers with its tuition grants and subsidies, it also encouraged new housing frontiers through its mortgage benefits.

One of the major barriers to home ownership in pre—World War II America was the size of the down payment. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act largely changed the rules by allowing a number of circumstances where the government would essentially guarantee the mortgage loan and encourage a policy of no down payment. The first entrepreneur who fully appreciated the impact of this provision was William Levitt, a New Yorker who had spent his wartime service managing the mass construction of buildings for the U.S. Navy.

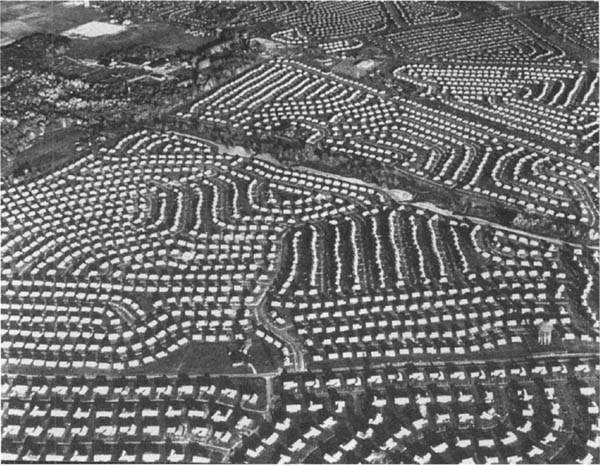

Soon after his discharge, the forty-three-year-old veteran, described as a “cocky, rambunctious hustler with the hoarse voice of a three-pack-a-day smoker,” bought twelve hundred acres of potato farmland near Hicksville, on Long Island about twenty miles outside of New York City. He turned his military organizational abilities into a construction campaign designed to entice young buyers into believing they could secure a part of the new American dream of home ownership in the pristine world of suburbia. From dawn to dusk in the muddy fields of a rising community called Levittown, the ground would shake as a convoy of tractors rumbled like charging squadrons of Sherman tanks. Every hundred feet they would dump identical bundles of lumber, pipe, boards, shingles, and copper tubing, all so neatly packaged they resembled enormous loaves of bread dropped by a bakery operated by giants. Then other massive machines fitted with a seemingly endless chain of buckets dug into the earth to form a trench around a twenty-five-by-thirty-two-foot rectangle. As men and machines engaged in a carefully coordinated operation, a new house would emerge largely complete every fifteen minutes until by July 1950 more than eleven thousand nearly identical homes sprawled across the fields, with parallel Levittowns rising in Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

The three original Levittown communities in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, above, symbolized the emergence of modern suburban lifestyles. By the sixties some Boomers would criticize their childhood homes as “ticky-tacky boxes.” (Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

A sale price of $7,990 bought mostly young couples a new home that, even if it would never be mistaken for a castle, offered a phenomenally child-friendly environment in which to raise a rapidly expanding family. Each home featured a picture window fronting a twelve-by-fifteen-foot living room, a bathroom, a kitchen, two bedrooms, and an “expansion attic,” which could and usually was converted to two more bedrooms and an additional bath. Each house was equipped with a refrigerator, stove, washing machine, fireplace, and built-in seven-inch television.

While young couples fired barbeque grills and their children raced tricycles and used their skate keys, most Americans who were either single or over thirty-five initially stayed well clear of the planned-community experience. Levittown and its hundreds of nationwide clones were worlds teeming with children and baby carriages but largely devoid of nightclubs and taverns. The first Levittown was peppered with huge new shopping centers, surrounded by enormous parking lots easily accessible from connecting roads. More than a hundred miles of winding streets and sidewalks teemed with vehicles partial to children, from station wagons to kiddy carts. If myriad descriptions were accurate, young mothers pushed strollers, held toddlers’ hands, dodged tricycles, and swapped recipes in the morning until an eerie silence descended on most of the community around noon. The next two hours were a mutually refreshing respite as children napped and mothers slumped into chairs or caught up on other chores. As late as 1950, only 10 percent of the children of Levittown were over seven years of age, encouraging one mother to explain that “Everyone is so young that sometimes it’s hard to remember to get along with older people.” The absence of an older adult presence contrasted with a seemingly limitless array of parks, playgrounds, baseball diamonds, swimming pools, and kiddie pools that seemed to cater to every whim, as long as it was a young whim.

Levittown was only the first of thousands of suburban “subdivisions” that would eventually define much of America’s postwar lifestyle and become one of the iconic images of film, television, and literature. If suburbia could sometimes be made into a fantasy—either dreamlike or nightmarish, depending on the narrator’s outlook—it was also the home of a substantial portion of the Boomer generation. Still, many postwar children grew up in places where their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents had spent their respective childhoods, and these locales continued to strike an important chord in the song of American culture. Children grew up in the rural farmland depicted on television programs such as Lassie and The Real McCoys; others experienced a small-town childhood, still a major topic of Normal Rockwell’s iconic artwork; many Boomers resided in large cities, as reflected in TV’s Make Room for Daddy. This author grew up in an “inner ring” suburb of Philadelphia, which had largely developed in the 1920s and 1930s. There stone Tudor singles mingled with brick twins and row houses, corner delicatessens, taprooms, and trolley cars, which hinted at an urban lifestyle while coexisting with the swimming pools, Little League fields, and barbeque grills that defined postwar suburban living. All of these environments featured many young couples with large numbers of children but also included senior citizens, single people, and childless couples, which made them appear slightly less Baby Boomer centered. Yet, in the postwar era, newer suburbs dominated by young couples and children often defined the Boomer experience in films, literature, and television. Since this suburban lifestyle offers both the distinctiveness of a new childhood experience and many elements of the more general experience of all Boomers, Levittown and its counterparts make a good introduction to the postwar home and family.

The physical makeup of a Boomer-era childhood home reflected the design of three prominent suburban models: colonial, ranch, and split-level. Colonials were, at first glance, the closest approximation to the “Victorian” homes characteristic of much of the Northeast and Midwest and popular in most other sections of the country since the turn of the century. These are the homes most often seen in 1950s and 1960s family situation comedies and films, and featured the most traditional living arrangements. A colonial had two full stories with living room, kitchen, and dining room on the ground floor, bedrooms and bathrooms on the second floor, and often a basement and/or an attic. Unlike their Victorian predecessors, however, colonials largely dispensed with front parlors, front porches, and pantries, substituting powder rooms, dens, and rear decks. This configuration provided the advantage of relatively large kitchens that could also accommodate a table for meals, less intrusive noise for children sleeping upstairs, and the possibility of relatively generous storage space. The two major drawbacks of colonials were that they tended to be more expensive than other models, and the stairs could become extremely annoying when having to carry toddlers or wash baskets.

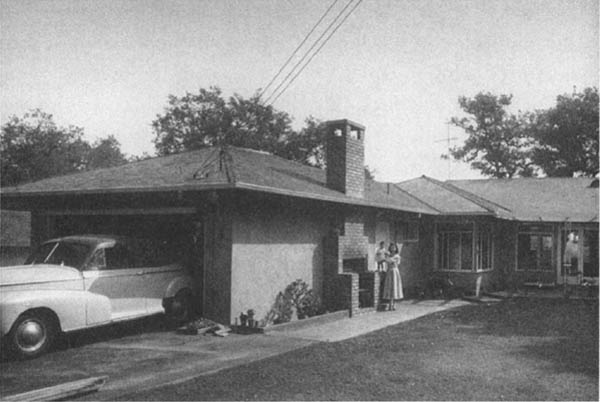

The most popular postwar suburban home model was the ranch house. The single-floor layout eliminated the tedium of stair climbing, but many families found more togetherness than they wanted with bedrooms in close proximity to living rooms. (Times & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

The ranch was probably the most popular home model for the entire Baby Boom childhood period. Ranches tended to be rather sprawling homes with virtually all the living space concentrated on one floor. These houses looked very contemporary, eliminated most stair climbing, and, like the colonials, might include a basement or an attic that could offer more room as families grew. This living arrangement was less frequently depicted on film and television but was the most common new housing in American suburbs.

The third home model was generally a compromise between colonial and ranch—usually, but not always, designated a split-level. This style offered three or even four floors, divided by stairs that were roughly half the extent of steps in traditional two-story homes. In most cases, upper levels featured bedrooms; middle levels had kitchens, dining rooms, and living rooms; and lower levels included laundry rooms, garage access, powder rooms, and the most innovative of postwar suburbia, a “family room” or “recreation room” that often included a television, record-player system, a new “recliner” chair or two, and perhaps a fireplace, pool table, or Ping-Pong table. In many homes this room might become a gathering place for younger members of the family while the living room was used by adults or reserved for relatively formal occasions.

Most of the new ranches and at least some of the colonials and split-levels had a feature that illustrated the downside of postwar tract housing. Many 1950s and 1960s homes were not only considerably smaller than their twenty-first-century counterparts, they were also more cramped and shoddily constructed than models built several decades earlier. Traditional attics and basements had become less than standard features on “contemporary” homes, creating a never-ending storage crisis. Bulky children’s items such as tricycles, bicycles, and strollers vied with lawn mowers, grills, and gardening equipment in crawl spaces, garages, and driveways. Even that icon of suburban upward mobility, the two-car garage, frequently became the no-car garage, containing every wheeled object except an automobile.

The interior of a new Boomer-era home was often equally cramped. Cost-cutting imperatives reduced halls to a claustrophobic width of thirty-six inches, which turned passage from one room to another into a complex maneuver when two family members met along the route. Many new kitchens had space for a counter and stools, but the absence of a traditional table often turned breakfast into a stand-up meal on the go. The combination of thin walls and one-floor design in a ranch home often made adult television viewing in the living room a major sleep impediment for younger children, who might have to put pillows over their ears to reduce laugh tracks and commercial noise. One of many Life articles on the realities of suburban living implied that behind the façade of cozy ranches were frayed nerves and petty arguments caused by close quarters and unstored toys.

Whatever the merits or defects of postwar homes, they became the setting for a frenetic social drama centered on new parents and their burgeoning families. While there was no “ideal” or “typical” Boomer family, some general patterns are noticeable. First, the average marriage age for young men and women was gradually falling until in 1957 it reached 21.5 years for males and 19.5 for females. This meant that a large percentage of girls were becoming engaged late in high school or very early in college. Newspaper wedding announcements featured great numbers of teenage brides and only marginally more mature grooms. Second, these young newlyweds started their families quickly, which in turn pushed the average family size toward four children. By the mid-1950s more families had six children than had one child, while childless couples seemed relegated to peripheral status in family dynamics. The cast of characters in these ongoing family dramas also included fewer non-nuclear family members as the number of grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins living full time in the same family home as mother, father, and children dropped substantially.

The family-life dramas that engaged young Americans across the continent showed considerable continuity with past counterparts but contained enough unique aspects to promote interest decades later. A peek into a representative 1950s home would often reveal an amazingly young, rather formally dressed mother barely out of her teens, organizing a household of several children and deputizing the slightly older ones to take some responsibility for their younger siblings while she cleaned, shopped, and cooked. In this occasionally magic and frequently hectic environment, older children became confidants to their young mothers as they formed a special bond based on their partial responsibility for the great enterprise of “family life.”

While spanking and screaming at children had not disappeared from parents’ corrective repertoire, the strict environment of earlier decades had mellowed considerably as many mothers exhibited the patience, grace, and intelligence of the well-known TV mothers—a June Cleaver, a Donna Reed, or a Harriet Nelson—while often interacting with far more children than their television counterparts.

Gender roles also seemed to be gradually softening as the postwar family structure crystallized. Far more postwar women drove automobiles than their mothers had, both through the necessity of a car-oriented suburban culture and a sense of empowerment that driving was not exclusively a male prerogative. In those suburbs with access to public transportation, the wife often logged more driving time than the commuter train—dependent father, who was now relegated to weekend and vacation driving in a vehicle that had tacitly become “mom’s car.” As driving errands now shifted to more of a female role, the rise of the “barbeque” culture turned more than a few men into amateur cooks. Contrary to myths that hapless 1950s males found heating a frozen TV dinner daunting, this era turned much of the outdoor cooking experience into a male domain. From backyard grills to picnic fireplaces, young fathers, with or without “World’s Greatest Chef” hats, became iconic figures of the period and often passed their skills to their sons. The gradual shift to more night and weekend hours, from pediatricians’ offices to supermarkets, also contributed to a softening of gender roles as doctors’ visits and shopping excursions more frequently engaged both husband and wife far more than the strict weekday hours of prewar shopping and services.

Gender roles among children were also changing, more than is apparent from looking merely at the doctor/nurse divide in medically oriented toys. The black toy doctor bag did have stern-looking glasses, absent from the white nurse bag, and included more active diagnostic instruments and fewer bandages. But the distinction between “cowboys” and “cowgirls” was much smaller, as girls were “allowed” to have guns, holsters, hats, and boots, much the same as boys.

Perhaps the most flexible gender relationships occurred as older children were often designated junior parents in the crowded households of the times. Many boys changed younger siblings’ diapers, took them for walks in strollers, and rode their bikes to the store with a grocery list from their mothers. Girls helped move heavy furniture, showed their little brothers how to play basketball, and helped their mothers wash and polish the car. Various levels of babysitting experience often depended more on age than on gender; few parents would hire an outside baby-sitter to watch younger children if there was a twelve-year-old son in the house, and at least some boys expanded their baby-sitting to include neighbors’ kids, just as girls took on newspaper deliveries in some communities.

Much of the image of American society from the late 1940s to the early 1960s is based on the concept of a comfortable but rather conservative lifestyle with relatively little questioning of the status quo. Yet investigation of contemporary sources reveals that discussions about optimal methods of parenting and adult-child relations were noticeable in almost every medium, and young couples were convinced and delighted that they were entering a new frontier of family relationships. In fact, period discussions about the 1950s equivalents of “soccer moms,” “helicopter parents,” and “tweeners” culture appear quite modern in tone. Yet, along with these recognizable concerns there are strong suggestions that the fifteen to twenty years following World War II were indeed “Happy Days” for both parents and their children.

Most important, this period represents one of the high points of family stability in the entire American experience. Earlier in the century, the high mortality of parents from epidemics, work-related accidents, and childbirth complications produced a strong possibility that childhood would be marred by orphanage residence, unpleasant stepparents, difficult stepsiblings, or placement with less than welcoming aunts, uncles, or cousins. Later in the century, after the Boomer age, skyrocketing divorce rates and a sharp rise in out-of-wedlock births created a parallel world of uncertainty and lack of affection for children. Yet for a relatively brief period, the optimistic portrayal of childhood and family experience in the media and literature of postwar America did reflect reality. Children lived in a world of stable and seemingly happy marriages where divorce seemed to be a feature primarily of the Hollywood acting community, and fatalities from work accidents, disease, and childbirth were substantially reduced. The only family distress that was significantly more likely in the early postwar period than in the twenty-first century was the far higher incidence of childhood disease. At best, most children and their frazzled parents lived through bouts of measles, chickenpox, and mumps, which, if seldom fatal, were rather serious illnesses requiring considerable bed rest and intense parental care. The majority of early Boomer children also experienced a painful trip to the hospital as pediatricians seemed obsessed about the health implications of swollen tonsils. Relatively few children escaped a tonsillectomy, whose pain and hospitalization were offset by the dubious promise of “all the ice cream you can eat” after the operation. But by far the most terrifying shadow hovering over any family was infantile paralysis, the polio that had crippled the recently deceased president and spurred the annual March of Dimes campaigns. The crippling or death of tens of thousands of Boomer children was quite possibly the single greatest calamity in postwar households until Dr. Jonas Salk joined Benjamin Spock in the pantheon of parental heroes when he perfected the first successful polio immunization vaccine in 1955.

The benign influence of relatively high levels of family stability was paired with relaxed discipline and heightened parental involvement that made the period a nostalgic era for children. American mothers of the period often appear as confident, friendly, caring young women who drove children to shopping centers, splashed them in a backyard pool, and served milk and cookies to a circle of avid television viewers. Fathers emerge as relaxed, strong, involved figures who were less likely to spend the evening with “the boys” in a local tavern or bowling alley and were now finding their stride as Little League coaches and scout leaders. But if the specter of childhood disease was the dark cloud threatening an otherwise stable family structure, excessive parental involvement now emerged as a less positive side of the “child-friendly” attitude of the period.

A 1958 article by Robert Paul Smith, a rising expert on parent-child relations, coined the mildly disturbing term “Big Brother Parents,” which hinted at an almost Orwellian control of childhood activities. Smith lamented the rise of “a well-intentioned horde of interfering parents who give their kids no chance to have fun by themselves.” In an almost eerie preview of twenty-first-century issues, the author insisted, “The way you play soccer now is you bring home from school a mimeographed schedule for the Saturday morning leagues. The schedule is arranged by a mathematical process of permutation that would take six mathematicians to figure out. Parents are now playing someone else’s game. All the parents who cannot refrain from interfering in the wonderful world of a child have invented a whole new modern posture—child watching.” Smith empathized with a young mother who complained that when her daughter was “initiated” in the Brownies, all the mothers had to be admitted too, a ceremony that concluded with an almost comic scene of the mothers standing in a line and reciting the Brownie oath. Similar articles reported that while young parents were often delighted that their children liked spending time playing under adult supervision, many of the youngsters were embarrassed when the parents made spectacles of themselves as Little League umpires or replaced their daughters when going door-to-door to sell Girl Scout cookies. A major question of the time was whether parents wanted their children to be more grown up, or whether parents wanted to be more like their kids.

At first glance the home setting for young Boomer children would look rather contemporary to a twenty-first-century observer. The house would be bright, airy, and well lit, the kitchen appliances would appear modern, and the youthful noise would be familiar. On closer inspection, substantial differences would begin to appear. In summer, the cool, quiet hum of central air-conditioning systems would give way to steamy warmth, only slightly moderated by noisy electric fans dotted around the house. Before the very end of the 1950s, entertainment and communication devices would most likely be limited to one black-and-white television with a twelve-to twenty-one-inch screen; a floor-or table-model radio in the living room; one or two black, dial telephones, one located in the kitchen, living room, or entrance hall with a possible second in the parents’ bedroom; and a “hi-fi” record player stocked with 33⅓ rpm albums.

A glance at children’s bedrooms would reveal two important differences from the twenty-first century. Depending on the age of the occupants, the bedrooms would include toy chests; posters of movies, comic-book heroes, or music celebrities; sports pennants and photos; and similar decorations. Few electronic devices could be found, and human child voices would be much more common than any other sound. Some fortunate children of the late 1950s might have their families’ old twelve-inch television sets if a new twenty-one-inch model had been purchased; some children would have a small plastic clock radio on a nightstand. Preteens might have a small record player capable of playing a stack of the new 45 rpm “singles” that emerged with the birth of rock music. A tiny number of relatively affluent preteens or early teenagers, especially girls, might have their own phones, but this was a coveted possession seen much more often on television or in films than in real bedrooms.

A second important difference, compared to the twenty-first century, was the bedroom with two or even three beds. The growing number of bedrooms in new home styles never kept pace with the increase in family size of the period, and the result was a premium on shared sleeping space. Most new homes featured three bedrooms, and since a fairly typical Boomer-era family had three to five children, bedroom sharing was almost inevitable. Most children’s bedrooms featured either two twin beds or a bunk-bed configuration, but a single twin bed and a double bunk were also common in families with five or more children or families with four kids with a 3-to-1 gender ratio. Given space limitations, families might allow mixed accommodations among young children, but this was usually a temporary stopgap before a move or home expansion.

A closer examination of other rooms in a Boomer household would reveal other technological limitations that often affected the childhood experience. A modern 1950s kitchen included a refrigerator and stove, sometimes in matching colors, and a sink that often came with a spray hose attachment. Microwave ovens were still primarily a figment of science fiction, and automatic dishwashers would be uncommon for another decade. The “TV dinner” was now available and heavily advertised but in fact was viewed largely as a backup or emergency alternative; few housewives would dream of serving them regularly. This level of technology had relieved much of the drudgery of a half-century earlier, but in food preparation and after-meal cleanup the mother could assume that she would receive at least some family help. A laundry room or basement would reveal the same mixed technology. Most homes now had an electric washing machine; relatively few still featured the external hand-operated wringer. But automatic gas or electric dryers were still a novelty until well into the 1960s, and wash day featured a backyard filled with intricate clotheslines with an array of clothes, towels, and sheets flapping in the breeze like colorful sails. Doing the wash also called for children’s help, and very few Boomer kids reached adulthood without knowing how to use clothespins or how heavy a basket of wet wash might be.

Thus even a cursory tour of an average Boomer’s childhood home would reveal three somewhat different realities compared to a twenty-first-century experience. First, technology was still relatively limited; second, privacy was very limited; and third, the concept of children’s chores was still an important part of family life. The many Boomer childhood ideas about cooperation, boredom, fun, and adult authority might be different from those of their children and grandchildren.

The children of this era fought over viewing preferences on the single television set, played Monopoly or Clue on the living-room floor with brothers, sisters, and friends, screamed that an obnoxious sibling had “cooties,” and helped one another put on snow boots that seemed to feature an infinite number of finicky buckles. A world of relatively large families and tighter household budgets guaranteed numerous variations on the theme of sharing, ranging from cutting jelly doughnuts in half to group ownership of some toys. Almost every household activity became an exercise in negotiating or bartering, yet these actions were so common that few children consciously thought about them.

A shared bedroom made privacy a luxury, and the limited capacity of hot-water heaters virtually guaranteed that a warm shower could turn frigid in the rush for the school bus. Yet there were always plenty of available players for Scrabble or Crazy Eights, and older brothers and sisters were more often protective and caring than obnoxious and bossy. This meant that unless a child was the oldest in the family, when Boomer kids made their first treks to school, they would not be alone. This comfort, however, was scarcely reassuring to the harried principals and teachers who watched a tidal wave of youngsters surge into their already bulging institutions. While Boomer homes might be crowded, it was the jammed classrooms that were now gaining national attention.