THE IMAGES of a young generation at play in the 1950s are impossible to avoid: freckle-faced boys adjusting Mickey Mouse ears or Davy Crockett coonskin caps, giggling girls gyrating to the motion of colorful Hula Hoops, smiling children leaning out of the windows of the family station wagon as they near a beach resort or picnic grounds. Whatever the specific type of activity, the Boomers, like most children of any generation, were engaged in an adventure that expanded their horizons outward from their homes to the nation or world at large. Yet, more than most previous generations, this very act of recreation and exploration encouraged massive adult discussion, debate, and commentary. The birth of 76 million children between 1946 and 1964 produced an enormous incentive to channel the energies of this youth tidal wave into positive directions. But for the main players in this drama, the kids, the leisure world of the 1950s would produce a nostalgia that would stay with them through their adult lives.

The boys and girls who would become the parents of the Boomers had already experienced their own magical world of play in the 1930s and 1940s. They had listened to Little Orphan Annie on the radio, read Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys books, followed comic-book heroes, and watched Dorothy travel from Kansas to Oz. Their world had offered Shirley Temple dolls, Red Ryder toy rifles, and Big Little books. But the magical world always had finite limits as depression and war instilled the need to sacrifice and make do with less. Now the prewar children had sons and daughters of their own, and much of the 1950s would be spent in an emotional tug-of-war. While the booming economy offered parents the opportunity to give their children more than they had experienced, the austerity of their own childhoods suggested that kids who received too much would become spoiled brats, unable to function well in a still conservative society.

The first hint that the Boomer generation would spend at least part of their leisure time differently from their parents could be seen in the transition in living-room furniture. The children of the 1930s and World War II had formed the one and only “radio generation.” The first decade of commercial radio broadcasting in the twenties held little of interest for children as the medium focused on news, farm reports, sports events, and recorded music. The more iconic programs—comedies, mysteries, and, above all, children’s shows—began in the early to mid-thirties. Boys and girls sprawled on living-room floors and lounged on couches or chairs, always with their attention directed to the radio set that held pride of place in the parlor. The sons and daughters of the “radio kids” generation also sprawled and lounged in much the same positions, but their attention was focused on a flickering black-and-white screen that replaced the radio as the magic carpet to new worlds and adventures.

The first children’s television hit show: the interaction between live actress Fran Allison and puppets Kukla and Ollie not only entranced postwar children but brought many adults into a charming and magical world that demonstrated the potential of the new medium. (Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

Remarkable new characters entranced Boomers and even their parents before the kids could even pronounce their names. Burr Tillstrom, a thirty-two-year-old puppeteer, teamed with Fran Allison, a middle-aged former teacher, radio singer, and actress, to present NBC’s huge hit Kukla, Fran and Ollie. Allison was the human mediator between Kukla, a balding, beetle-browed puppet with an efficient, slightly superior air, and Ollie, a dragon with one tooth and a playboy personality who was a severe trial to Kukla’s patience. “It is the undeniable opinion of many television set owners,” one magazine wrote, “that this is the most delightful program on the air.” For the first time in history, young parents could sit next to their wide-eyed children in their own living room and, for a moment, learn once again how much fun it was to believe in the other realities their television set offered.

Tillstrom and Allison soon had competition in the form of another, more frenetic human-marionette interchange. The Howdy Doody Show featured a live audience of exuberant preschoolers seated in a row of bleachers called the Peanut Gallery. The two stars of the daily show were genial, burly “Buffalo Bob” Smith, dressed in a Western-style fringe outfit, and his puppet counterpart, Howdy Doody, a freckle-faced redheaded boy dressed in miniature plaid shirt, neckerchief, and blue jeans. Buffalo Bob’s major nemesis was the irrepressible clown Clarabelle, who communicated only through honks of a horn while spraying victims with seltzer bottles, while Howdy’s antagonist in the town of Doodyville was the mean, supercilious banker Phineas T. Bluster. The show was fast-paced yet gentle. By episode’s end, Clarabelle would behave, Mr. Bluster would prove capable of good deeds and empathy, and the television audience would learn much about friendship and conflict resolution.

Kinescope recordings of Kukla, Fran and Ollie and Howdy Doody often appear primitive compared to Sesame Street and The Electric Company, yet for the first cohorts of Boomers and many of their parents they offered access to an almost unlimited universe beyond the home. Because television was so new, it carried some of the same shared wonder now produced by the internet. Even as these original programs gave way to more sophisticated fare, some portion of the special bond between television and the first generation that grew up with the medium would remain.

Television is the leisure activity most associated with children of the fifties and early sixties, not because it was the Boomers’ dominant recreation—it probably was not—but because of their unique status as the first “TV generation.” The limited number of channels in the precable era, the limited hours each station broadcast, and the limited number of television sets in each household ensured that the youngsters of this era could never match their children or grandchildren in the opportunity to watch television almost continuously. Yet these very limitations created a much stronger sense of shared community, an almost village-like experience of viewing in which family members, friends, and schoolmates often watched the same program so that discussion of a particular show might carry over from the living room to the schoolyard the next day. The viewing of some evening programs became family events.

Boomer children would generally participate in three sometimes distinct but overlapping television experiences: children’s television, specifically directed at young viewers, in which adults were merely tolerated; family programs, which sought to attract both children and their parents; and adult-oriented shows geared for a more mature audience but either surreptitiously or openly viewed by children as a glimpse of a world beyond childhood. Television viewing was also a changing universe: the oldest Boomers gradually left the more juvenile shows to their younger siblings, and the networks frequently canceled programs and forced children to experiment with a new show, so that no two television seasons were ever exactly alike. Yet even if the world of early television was hardly static, there were enough characteristic programs or formats to provide insight into the Boomers’ viewing experience.

The children’s programs on the networks (NBC, CBS, ABC, and, early on, DuMont) usually featured action geared to short attention spans, sometimes used children as important characters, and advertised products aimed at a young audience. Children’s programs could be live, animated, or a combination of the two, and would usually be broadcast weekday mornings, afternoons, or early evenings, and Saturday morning, either live or on film.

The most successful weekday children’s program of the 1950s was the Mickey Mouse Club, which captured the attention of much of the young population of that era. The program featured a cast dominated by talented, photogenic children between eight and twelve years of age, who danced and sang in almost vaudevillian routines, introduced by the only significant adult presence, Jimmy Dodd. While all the Mouseketeers quickly enjoyed fan clubs, a few children became early idols of Boomer kids. The two youngest performers, eight-year-olds Cubby O’Brien and Karen Pendleton, were precocious, cute, and the only kids who were actual Boomers themselves. Twelve-year-olds Annette Funicello and Tommy Kirk were the most versatile, which led them to post-Mousketeer acting and singing careers. One of the most attractive elements of the program was that each day had a separate theme, such as “Fun with Music” day, and stage action was interspersed with filmed serials, such as Spin and Marty and the Hardy Boys episodes. Product tieins to the series were heavily advertised, and millions of children clamored for the attachable mouse ears that would become one of the symbolic images of Boomer childhood.

The hugely successful Mickey Mouse Club usually led into more localized children’s fare in the time slots just before or even during dinnertime. Many local stations found a profitable niche for recycled 1930s and 1940s comedy shorts and cartoons, so that many Boomer children watched various Three Stooges Shows and Popeye Theaters hosted by local personalities. More than a few perplexed children tried to decipher Swing Era slang and jokes or wondered why Popeye was fighting 1950s allies such as the Germans or Japanese.

Daily afternoon programs were followed by early evening primetime shows that emphasized a family-friendly or child-friendly component. Rin Tin Tin, Lassie, My Friend Flicka, and Circus Boy were filmed dramatic series in which the central characters were children, often orphaned or in a single-parent home, and frequently paired with a highly intelligent animal. The evening time slots of these programs ensured at least some level of adult audience, and commercials were a mix of general family products and items of specific interest to children.

Prime-time children’s programs either competed with or led into the broadest category of network television programming, shows developed for the entire family with sponsors geared to adult purchase. Ten years after the first tentative steps toward network broadcasting, a fairly standardized series of formats began to dominate mid-evening family viewing. A glance at a network program grid from 1957 reveals a variety of formats centered on programs that would become icons of fifties popular culture. Situation comedies such as I Love Lucy, Father Knows Best, and Ozzie and Harriet; Westerns such as Maverick, Wyatt Earp, and Sugarfoot; and comedy/variety programs including Jackie Gleason, Red Skelton, and George Gobel were eagerly anticipated events for all age groups. Only the enormously popular and mostly rigged quiz-show format of Twenty-One, Sixty-Four Thousand Dollar Question, and Tic Tac Dough was an endangered species, and as congressional pressure forced their cancellation, they were quickly replaced by Donna Reed, Leave It to Beaver, and Bonanza. Generally Westerns had enough action and comedies offered enough slapstick or young characters that children were entranced, even if the advertisements were for floor wax or deodorant. Since rules governing bedtime varied by household, not all kids saw all of these programs, yet a family audience encouraged a discussion about shows that attracted children as listeners or participants, far more than twenty-first-century parents might imagine.

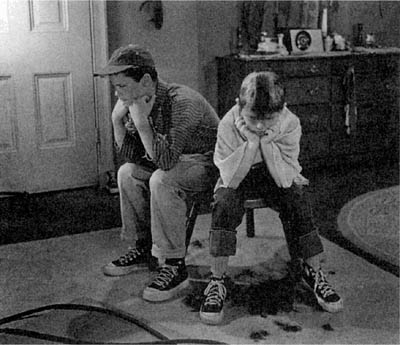

The situation comedies of the postwar era, like Leave It to Beaver, became a shared experience for all members of Boomer-era families, even if real households were considerably larger than their TV counterparts. (Getty Images)

For most children, the least accessible television programming was the increasingly mature fare after 9 or 10 P.M. Even the most “adult” drama then would receive a PG rating in modern coding, but many fifties parents were nonetheless concerned about the impact of television on their children. Some children who were able to negotiate lenient terms from their parents were sometimes permitted to sample “adult” programs such as Perry Como or Andy Williams, simply because the “mature” character of the program was its music content, which would be supremely boring to a ten-year-old. Slightly older children might be permitted to stay up late enough to view weekend episodes of moderately scary but not particularly violent or suggestive shows, such as One Step Beyond or Twilight Zone. Programs that were extremely violent or sexually suggestive, however, represented the parental line in the sand, as the furor over the body count and implied sexuality of the late fifties program The Untouchables testified. Still, this reality was far removed from V-chips and parental lockboxes, and children’s viewing habits tended to remain rather tightly under adult control and supervision.

By the late 1950s more than 90 percent of households had television sets. Yet many of children’s leisure-time activities exhibited direct continuity with those of prewar youngsters. In the summer, for example, many beach resorts, camping areas, and other vacation spots were too far from cities with television stations to provide viewing opportunities. And more than a few parents felt that in summertime their children should be doing something other than watching reruns, so that in many cases the breakdown-prone TV sets weren’t repaired, or adults imposed stringent viewing restrictions during vacation months.

One classic prewar activity in a world of limited television channels and summer “blackouts” was that other visual medium, the motion picture. Postwar children had fewer movie theaters and fewer films than their parents had enjoyed in their childhoods, but most of the thirties and forties movie experience was still largely intact. Much like their parents’ era, Boomer movie viewing was roughly divided into two experiences, Saturday matinees for kids and evening shows with parental accompaniment.

Urban or suburban neighborhood theaters accessible by foot or bicycle, and newer theaters in shopping centers that catered to auto traffic, both provided that staple of childhood recreation, the Saturday matinee. These shows offered a low admission price, often a quarter or half-dollar, and tended to have an audience composed primarily of children, with older siblings chaperoning younger brothers or sisters. The features often included one or two low-budget comedies, such as Ma and Pa Kettle or Francis the Talking Mule, or equally low-budget science fiction, horror, or World War II films, supplemented by strings of cartoons that offered the advantage of being in color in the theater while on television they were only black and white. Many parents were happy to unload some or all of their children for a Saturday afternoon, much to the consternation of harried ushers and candy-counter personnel. Altogether the experience was close to what the Boomers’ parents had known in the 1930s—and even their grandparents remembered from the silent-film era.

The family outing to a movie theater in the evening, a major part of social life in the 1930s and during World War II, continued to be a major event throughout the fifties and early sixties. The film industry was initially terrified that the advent of television would remove the incentive for families to leave the house and pay for watching films. These fears were partially realized: two or three visits to the Bijou now became a more occasional, yet more special, event. Three film genres were still able to entice mother and dad to take the children to the movies. First was the “spectacular,” using new technologies in sound and wide screen, often involving a film with religious or moral overtones. Among the most successful films in this category were The Ten Commandments and Ben Hur. The second theme focused on Walt Disney’s ability to entice families to view a combination of re-released and new animated features. In the postwar era parents relived Dumbo and Snow White with their children while all experienced first-time screenings of Lady and the Tramp and Sleeping Beauty. Finally, Disney and some competing companies updated the prewar family comedy and adventure movies, offering the added attraction of a wide screen and color, not available at home. These offerings included The AbsentMinded Professor and, remarkably, a compilation of the three-episode television presentation of Davy Crockett. A final postwar movie theme, developed with little concern for a young audience yet experienced by a great many Boomer children, centered on adult tastes in music. The fifties and early sixties were replete with biographies of famous big-bandleaders, such as The Benny Goodman Story and The Glenn Miller Story, and film versions of Broadway musicals such as My Fair Lady and The King and I. All these films offered catchy tunes and relatively accessible plot lines, but this part of the “family” movie experience was probably more memorable for the parents than the kids.

If television represented the most visible break with earlier childhood leisure activities, and movies maintained the most significant bridge between the generations, the toy and game industry offered traditional play activities as well as new experiences. The parents of the Boomers had grown up in a period when a cornucopia of toys were mass produced and heavily advertised on radio, in newspaper ads, and in increasingly colorful catalogues. The children of the 1930s who lived in families that were less damaged by the depression had access to erector sets, electric trains, Shirley Temple dolls, Red Ryder toy rifles, and Monopoly games. Many of these toys were colorful, sturdy, and durable, if also made of relatively expensive materials that limited their accessibility. If metal toy dirigibles, electric trains, and dollhouses represented the Age of Metal, Boomer children would be the first to encounter the Age of Plastic. It is no coincidence that the most popular range of train accessory buildings for budding railroad tycoons of the fifties and sixties was labeled “Plasticville,” and offered distinctive postwar structures such as “Tasty Freeze” ice cream stands, spacious supermarkets, and even pastel-colored motels, producing a far different rail layout than the tin litho structures of the thirties. And while Boomer children continued to develop holiday and birthday lists around Sears, Macy’s, Lionel, or American Flyer catalogues, television advertising now allowed them to see their desired toys in action, which hardly discouraged demand.

The large numbers of children coupled with an escalating number of toy lines produced conflicting tastes. Children argued whether Lionel or American Flyer made the best trains, whether Ideal or Mattel made more realistic dolls, and whether Milton Bradley’s Easy Money was superior to Parker Brothers’ Monopoly. Still, it is possible to paint a broad canvas of the postwar generation at play.

One common element of Boomers at play was the formalization of traditional role-playing, encouraged by the emergence of relatively inexpensive plastic toys. Role-playing included historical re-creations, such as the Wild West and the recently ended World War II; contemporary adult occupations, such as physician or nurse; and a speculative yet exciting future revolving around space exploration that, at least theoretically, might become reality during the children’s adult lives.

The prewar interest in frontier exploits, transmitted by numerous films and radio programs, became even more pronounced in the fifties and sixties. Not only were there big-budget color movies, but television rapidly became a giant corral for Western series. By 1959 twenty-six prime-time series were concerned with frontier life, with nearly twenty other syndicated Western programs airing on Saturday morning and weekday early evenings. Many of these shows, including Bonanza, Gene Autry, and Roy Rogers, had extensive toy company tie-ins that allowed boys and girls to reenact the Wild West in their own homes or neighborhoods with cowboy or cowgirl hats, fringed jackets, boots, and authentic-looking weapons.

Most Boomers had at least one parent who had been actively involved in some aspect of World War II, and while some of these men and women were reluctant to discuss their experiences, many others served as models for role-playing activities. A degree of realism was provided when the toy companies’ weapons and accessories were supplemented by children’s use of their parents’ canteens, helmets, rank insignia, and even uniform articles, as imaginary Axis replaced Western outlaws as adversaries.

The postwar period saw role-playing in a future world seriously challenge the reenactment of historical events in children’s play experiences. Boomers’ parents had had a taste of science fiction with the comic-strip and film serials of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon and related toy spinoffs. But the “Atomic Age” of the fifties and early sixties prompted a quantum leap in these activities among postwar children. This was the first golden age of science fiction films with robots, spaceships, and futuristic weapons featured in movies such as Forbidden Planet, Invaders from Mars, and This Island Earth, and in television programs such as Tom Corbett—Space Cadet, Space Patrol, and The Jetsons. Along with the real-life exploits of Sputnik and NASA’s Mercury programs was the imaginative extrapolation of these events by children.

While one aspect of role-playing was based on children becoming actors in a mini-drama, ranging from contemporary medical care to wartime combat, another major element of this experience was to use toys as surrogates in a miniaturized version of real or imaginary events. In the fifties and early sixties, girls often created this “small world” through dolls, boys through action figures and model railroads.

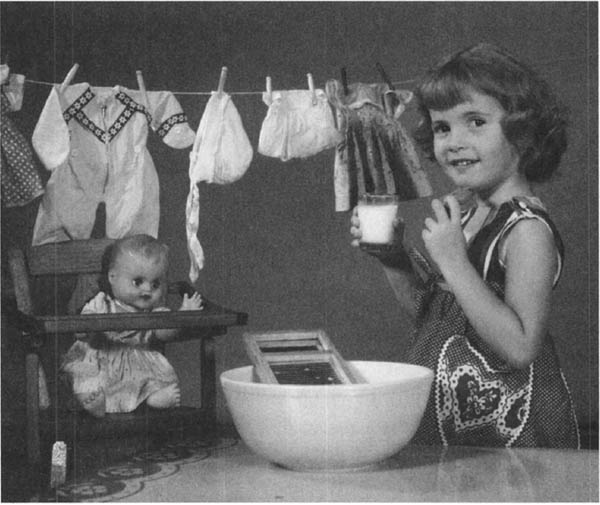

One of the most notable effects of the postwar revolution in plastics was the greater sophistication of dolls and related accessories available to Boomer girls. Prewar girls might have thought it marvelous that their doll could open and close its eyes, but postwar dolls could require diaper changes (Betsey Wetsy) and even hold a minor conversation (Chatty Cathy). The age of plastics also created a miniature modern household universe in which sinks had working faucets that sprayed real water, refrigerators had tiny ice-cube trays, and stoves had battery-operated burners that lit up like a real oven. Just as their mothers were managing an increasingly complex household, daughters were mirroring much of this experience in miniature, on a level unheard of even a generation earlier.

Probably the most pervasive doll-oriented development of the era occurred just as the oldest Boomer girls were making the transition from childhood to adolescence. At the very end of the 1950s the Mattel Corporation introduced the Barbie doll, which instead of looking like a baby or toddler, was designed to be an attractive, fashion-conscious teenager. Along with boyfriend Ken and little sister Skipper, Barbie offered the possibility of a miniature teen life, with so many wardrobe changes and accessories that Mattel would soon emerge as one of the leading American clothing manufacturers. Barbie would take the role-playing of doll activities from simulated motherhood to a primer in adolescent relationships just as Boomer girls were making this transition themselves.

The booming toy industry of the fifties and sixties encouraged young girls to replicate many aspects of their mothers’ homemaking experience. (Lambert, Hulton Archive)

As girls’ role-playing was increasingly defined by Barbie, Boomer boys were initiated into a more warlike competition with the emergence of G.I. Joe. Before the postwar boom in plastic toys, boys had created a military universe through lead or tin toy soldiers and a transportation universe of metal cars, trucks, and model railroads. One significant limitation of these generally sturdy, colorful toys was that they were so expensive that a child’s “army” might include only twenty or thirty soldiers or cowboys, and home rail empires were limited to one or two trains and a handful of buildings. This situation began to alter radically during the decades after World War II. Toy companies such as Marx began selling new plastic figures ranging from 35 mm to 60 mm in size for a nickel or a dime each, while combining elaborate sets, including figures, forts, buildings, and accessories, for about five dollars. These included play sets based on television programs, such as a Fort Apache set from Rin Tin Tin and Nottingham Castle from Robin Hood, as well as World War II and contemporary military forces. In the wake of Barbie’s success, toy companies enlarged the size of the figures to six to twenty-four inches and offered changes of uniforms, weapons, accessories, and other features in a figure that was rapidly emerging as a military doll. The most iconic of these figures, G.I. Joe, set the stage for an action-figure boom that would explode during the 1970s with the emergence of the Star Wars films.

The arrival of 76 million children between 1941 and 1964 guaranteed that Barbie and G.I. Joe would not be the only new toys to tempt boys and girls. Toy companies delighted children, and sometimes their parents, with Mr. Potato Head, Slinky, Hula Hoops, Twisters, Wiffle ball sets, and Silly Putty. Some game manufacturers introduced Scrabble, Battleship, The Game of Life, and an “electronic” football game where miniature red and yellow players seemed to circle endlessly on a green metal gridiron. Game shows, such as Concentration, Tic Tac Dough, and Dotto, promoted their home versions. The profusion of new toys meant that children’s wish lists often grew so long that even relatively affluent parents had to disappoint their children.

The emergence of television and the expansion of the toy inventory convinced many teachers and parents that the era of reading for pleasure was largely over. In one sense they were correct, as curling up with a book was no longer the only diversion on a rainy afternoon or a snowy evening. Yet television channels and broadcast times were still relatively limited, and toy boxes were not quite so overflowing that children could not still be tempted to escape to a world of print that was at once familiar and new to their parents.

Books that bridged the time between the 1930s and the 1950s included The Bobsey Twins, Nancy Drew, and The Hardy Boys series, which often included new cover artwork but otherwise remained as popular to Boomer children as to their parents. On the other hand, comic strips and comic books were undergoing more significant changes. By the end of the fifties a few prewar comic strips still inhabited the Sunday comics section of the newspaper, as Blondie, Mutt and Jeff, and Henry still attracted kids’ attention. But newer strips, including Beetle Bailey, Dennis the Menace, and Peanuts were emerging as stars. Most newspapers could carry only a finite number of daily and Sunday comics, and Katzenjammer Kids, Little Orphan Annie, Buck Rogers, and other icons of the thirties often surrendered their places to a new generation of characters.

The world of comic books was somewhat less constrained as the number of publications was limited only to the ability of children to afford them. Therefore many of the most visible comic heroes of the thirties remained more or less intact a generation later. Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and The Flash were still very popular, but plot lines changed in several areas. Superman’s enemies tended to be extraterrestrials rather than gangsters, as befitting the emergence of atomic power and possible space exploration. The Man of Steel had also acquired a female teenage cousin who was soon featured in her own comic book. Supergirl joined Lois Lane as a strong female role model with her own plot lines where Superman was a relatively peripheral character. Also, in an ironic twist, D.C. Publishers launched a Superboy comic book chronicling adventures in the Smallville of the 1930s, which had been the contemporary time frame of the original adult character.

As fifties and sixties superheroes were called upon to deal increasingly with visitors from outer space, as opposed to gangsters or spies, publishers added anthology-oriented science fiction comic books, such as Strange Adventures and Mystery in Space. The relatively few continuing characters in these publications possessed no supernatural powers but were usually ordinary individuals faced with extraordinary situations, such as the Atomic Knights, who used specially treated suits of armor to survive the distant post-nuclear-war future of 1999.

While this was considered the “Silver Age” of comic book superheroes, many Boomer children paid just as much attention to more comedy-oriented comic books. Archie, Nancy, Little Lulu, and Dennis the Menace were all top-selling franchises. Walt Disney used comic books to feature characters that were less prominent in his on-screen cartoons, probably the best-selling feature being Donald Duck’s mischievous nephews Huey, Dewey, and Louie, and Donald’s rich, cantankerous uncle, Scrooge McDuck. This quartet largely pushed Donald to the background in the comic book universe and introduced characters that would become particularly identified with the Boomer generation.

The combination of television, a much wider range of affordable toys, a significant increase in child-oriented films, and the expansion of children’s book and comic-book titles guaranteed that Boomer children would have access to a cornucopia of leisure activities unprecedented in the nation’s history. Yet the sheer size of this generation of children persuaded more than a few parents that organized, adult-directed activities were the best antidote to watching a youth culture spin out of control.

The fifties and sixties were a time not only of Hula Hoops and hopscotch but also of Little League, Brownies, Cub Scouts, and Campfire girls, when the true prototype of “soccer moms” and “football dads” emerged on the American scene. The casual pickup game on the local sandlot gradually gave way to the Tri-State Laundry Cubs meeting the Pepsi-Cola Yankees in a contest directed by adult coaches and supervised by adult umpires. Little Leagues in turn soon shared attention with Pop Warner football, Biddy Basketball, and a number of youth soccer leagues. A smaller but growing parallel universe of softball, basketball, soccer, and cheerleading programs attracted thousands of young girls to organized sports.

Millions of Boomers seamlessly traded baseball or cheer-leading uniforms for the blue shirts and yellow neckerchiefs of Cub Scouts or the brown beanies of Brownies, as scouting seemed to grow in geometric progression with young moms shuttling between den-mother duties for their sons and helping distribute Girl Scout cookies with their daughters.

As in any cross-generational conversation, it is not difficult to imagine the children and grandchildren of the Boomer generation rolling their eyes in disbelief as middle-aged adults fondly recount watching grainy black-and-while television programs or playing with decidedly low-tech toys. Children of more recent decades, exposed to a sensory bombardment of video games, high-definition cable television, and iPods, wonder how anyone could have had fun in a far more unplugged era. Yet the iconic images of midcentury childhood—Hula Hoop contests, smiling children in Davy Crockett caps, and mesmerized attention to the antics of Howdy Doody—are not illusions or gross exaggerations. The children of that era somehow instinctively knew that they lived in a magical time that could never be fully replicated. Boomer children certainly captured the attention of the adult world in the fifties. The one complicating factor was that these kids were fated to share the spotlight with slightly older youngsters who in some cases were their brothers and sisters. These siblings were producing their own iconic images as America’s first “teenagers.”