FRIDAY MORNING, January 20, 1961, dawned cold and blustery in Washington, D.C., as the nation’s capital joined most of the Northeast in digging out from the third major snowstorm in as many weeks. Yet by noon the White House and the Capitol were bathed in radiant sunshine that produced an almost blinding intensity as it reflected off the new frozen mantle. Residential areas in the city and suburbs teemed with children taking advantage of a snow day to engage in sledding and snowball fights that were relatively unusual in the region. Not far from these frolicking youngsters, a dramatic national event was unfolding. Dwight Eisenhower, at that time the oldest man to serve as president, was about to turn over the reins of government to John F. Kennedy, the youngest man elected to that office.

The newly inaugurated president was a parent of Boomer children and the first occupant of the White House who had been born in the twentieth century. His exceptionally youthful good looks were enhanced by his even younger wife, Jacqueline. The new first couple could have fit comfortably into any gathering of young husbands and wives engaged in managing their exuberant young children while socializing with other adults. As the president delivered his rousing, often-to-be-quoted inaugural speech that was noticeably pitched toward young Americans, the oldest Boomers were midway through their first year of high school while the youngest members of their generation would not be born for nearly another four years. Yet when Kennedy issued his clarion call for young citizens to consider what they could do for their country, not what their country could do for them, the message resonated through an entire generation, however many years they were from voting age.

John and Jacqueline Kennedy’s thousand days in the White House would soon be compared to Camelot, the smash Broadway musical that chronicled the mythological world of King Arthur and his wife, Guinevere, and their attempts to secure decency and freedom in a barbaric and warlike world. Much like King Arthur’s reign, the Kennedy years would emerge as a potent mixture of factual events, speculative theories, and near myth, in which the line between reality and fantasy seemed permanently blurred. For Boomer children this was an appropriate combination, for the first years of the 1960s would offer nostalgic memories and a seductive spectrum of possible alternate realities if destiny had not intruded on a Dallas motorcade.

Boomer families and the Kennedy family were entwined almost immediately. Images of John Jr. crawling under the Oval Office desk, Caroline hunting for Easter eggs on the White House lawn, the grim family vigil as newborn Patrick wavered between life and death—all resonated with young families in the early sixties. For Boomer children, the Kennedy mystique was furthered by photos of touch football on the Hyannis Port beach, presidential promotion of physical fitness in schools, and Kennedy lookalike comedian Vaughn Meader’s uncanny duplication of the president’s vocal exhortations. Jacqueline Kennedy engaged millions of young mothers as she announced proudly that her children were “Spock babies,” and her traditional pillbox hats and bouffant hairstyles set fashion modes in even the smallest communities. Growing up in the Kennedy era would emerge as a major subset of the motion picture industry as Boomers replayed the sounds and the sights of that period in American Graffiti, Animal House, Dirty Dancing, and Hairspray.

Much of the aura of the Camelot White House was a product of the relationship of John and Jacqueline Kennedy and their Boomer children, Caroline and John Jr. (John F. Kennedy Library)

While historians continue to debate whether the Kennedy era was the tail end of the fifties or the precursor of the more radical late sixties, many Boomers old enough to remember those years would agree with neither premise; they would contend that Camelot was simply unique. It was the scariest part of the cold war, with the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis, but it was also a time for new fashions, new music, and new ideas that extended beyond the political and economic aspects of the New Frontier. Somewhere between nostalgia and reality, the Kennedy era seems to provide a tangible bridge between the fifties and the sixties, especially in relation to the youthful concepts of the children who lived through the experience.

During the Kennedy years, postwar babies poured into the secondary school system and by 1963 occupied every grade level from kindergarten to senior high school. For the first time school officials could no longer transfer resources and personnel from less-crowded grades to overcrowded grades; now all grades were overcrowded. Even as new schools were built, finding teachers for them proved difficult as the average stipend of $4,000 a year was still less than enticing for a college graduate who could earn 50 percent more in the private sector. Harried principals played endless academic shell games in their attempts to cover all classes. When a new eleventh-grade English teacher was hired, the principal might shift the incumbent instructor to the still vacant eleventh-grade social studies slot because he or she had taken two or three history courses in college, and that experience might be just enough to keep ahead of the students. Young graduates with biology certification might find themselves teaching even more short-staffed chemistry courses, with vague promises that a certified teacher in that field might eventually be found.

The new president placed education among the top three or four concerns for his administration, and by 1963 school spending had risen to 6 percent of the Gross National Product, compared to 3 percent in 1946. The knowledge industry now rivaled manufacturing as an American activity, as the 50 million students enrolled in schools nearly equaled the number of full-time workers. Beyond the formal classroom, the emergence of communications satellites, cable television, automatic copying machines, and touch-tone telephones signaled the beginning of a new communications revolution that would increasingly affect Boomer children.

Just as these children were offered tantalizing glimpses of a “Jetsons”-like future, they also encountered a glimpse of a possible Armageddon far more terrifying than even the worst days of the Sputnik crisis. Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight Eisenhower, had countered the emotional shock of Soviet space spectaculars and the blustering threats of Soviet chairman Nikita Khrushchev with the calm demeanor of a former military commander who knew that his own country was far stronger. Khrushchev viewed the less experienced, younger Kennedy as more susceptible to threats and nearly ignited a nuclear holocaust. Few Boomers were old enough to understand the intricacies of East-West rivalry over access to West Berlin, the construction of the Berlin Wall, or the discovery of Soviet missiles based in Cuba. What they did see was massive construction of fallout shelters in new schools, national magazine and television features on how to turn family basements into shelters, and grim official hints that “duck and cover” in the classroom might be useless in a Soviet missile barrage that was calculated to kill more than half of all Americans instantly while leaving millions more to die slowly of radiation poisoning.

The classroom Civil Defense films of the fifties had focused on the terrifying but still somehow limited threat of a handful of Soviet bombers penetrating a powerful air defense to drop relatively primitive atomic bombs. Now, as sabers rattled over Berlin or Cuba, even relatively young children were informed that there was simply no defense against an enemy missile that could reach the United States minutes after launch with a payload of death that surpassed that of a hundred 1950s bombers. A frightening film watched by more than a few children in its 1953 release was Invasion USA, which depicted a Soviet ground invasion and partial occupation of an unprepared America. A decade later, films such as On the Beach, Dr. Strangelove, and Fail-Safe implied that much or all of the nation might be annihilated in a nuclear conflict.

If there was a moment when Boomers who grew up during the cold war seriously questioned whether they would live to see adulthood, it was during the spectacular autumn of October 1962. Children and teenagers familiar with stark nuclear-test films and multiple episodes of television programs such as One Step Beyond and Twilight Zone, depicting the many terrors of nuclear war, now saw their nation reach the precipice. On Monday, October 22, with military mobilization and defense alerts as the backdrop, President Kennedy interrupted regular television programming to announce a naval blockade of Cuba and a strong hint that Soviet failure to remove their missiles from that nation might lead to a nuclear exchange. Younger children considering Halloween costume options and teenagers moving toward a driver’s license, first date, first kiss, or first prom sat in stunned silence. With varying levels of comprehension, they realized that neither Halloween nor the homecoming dance might come this year, or perhaps ever again. American schools and civil defense agencies had done a comprehensive job of alerting children to the dangers of nuclear war; now perhaps they thought they had done their job too well as World War III seemed to become an imminent possibility.

During the next few days the long-feared nuclear war very nearly happened, and as Soviet ships probed the American naval blockade, CBS anchor Walter Cronkite described a litany of probable moves and countermoves that he strongly hinted would end in war unless miraculously short-circuited. Then, as one Kennedy official noted, Washington and Moscow went “eyeball to eyeball,” and the other side “blinked.” Children across the nation took cues from their parents and collectively exhaled. Suddenly the failure to study for an upcoming math test would actually (and thankfully) once more have consequences. Now it again mattered whether your mother purchased a Casper the Ghost costume or turned you into a Halloween ghost with homemade materials.

None of the 76 million Boomers would see the cold war end during their childhood or even during their young adulthood. Soon after the Cuban Missile Crisis, the struggle between the United States and Communist powers would push the nation into the war that defined the Boomer generation and produced conflict at home as well as abroad. Yet once those October days had passed, and trick-or-treat and Halloween dances had pushed war fears into the background, the collective near-death experiences of Boomer children gradually returned to activities that would later reignite the nostalgia for Camelot. The United States and the Soviet Union quickly installed a “hot line” communications system that at least made accidental war less likely. In June 1963 the young president, in a dramatic commencement address at American University, emphasized the commonalities, rather than the differences, between the rival powers and set the stage for a nuclear test ban. As young Americans watched their president mobbed by cheering Europeans from Dublin to Berlin, and meeting with leaders who always appeared much older, the link between the young leader and the Boomer generation seemed almost magical.

Children who lived during the Kennedy era experienced a moment in American youth culture that continued to fascinate Boomers far beyond the tragedy of Dallas. Almost as soon as the sixties ended, movie producers enticed patrons with catchphrases such as “Where Were You in ’62?” and used the New Frontier era as a backdrop for Catskill dance contests, college food fights, and Baltimore teen rebellion against segregation. Probably 50 million Boomers were old enough to experience the Camelot years on some level, and most of the remaining members of that generation participated indirectly through “Oldies” music, retrospective films, or DVDs of period television series. What they witnessed was a transition in which television, films, popular music, and fashion would ultimately make the Boomers a prime target of attention.

In the early sixties two television programming trends and a significant technological innovation influenced Boomer viewing habits and their interaction with other family members. First, beginning in 1962, the television networks dropped most of their Westerns and filled many of these time slots with programs centered on World War II themes. Program developers who had exploited every conceivable aspect of the frontier experience now treated the recent global conflict from multiple angles. Combat!, The Gallant Men, and Twelve O’clock High focused respectively on the war in France, Italy, and the bomber offensive against Germany. McHale’s Navy and Broadside provided comic views of the Pacific war, featuring the crew of a PT boat and a detachment of WAVES. The Rat Patrol chronicled the North African campaign, and Garrison’s Guerrillas delivered stories of undercover operations and spies. While historical accuracy and plot development varied enormously, these programs offered Boomer children a new perspective on the wartime experiences of their parents and an opportunity for discussion with them about this defining event. Every character, from the gritty bravery of Sergeant Saunders of Combat! to the officious pettiness of Captain Binghamton of McHale’s Navy, provided a backdrop for family interchange between the “Greatest Generation” and their postwar heirs.

While this trend encouraged Boomers to see recent historical events from their parents’ perspective, the other major programming shift emphasized the comic and dramatic aspects of growing up in the 1960s and sparked a different kind of dialogue. Comedies such as Dobie Gillis and Patty Duke viewed the high school experience through the interactions of teenagers and their parents. Mr. Novak added the perspective of an idealistic young English teacher and a somewhat more cynical school principal. Fair Exchange offered the intriguing premise of transatlantic comparisons of teenage experiences through young female exchange students.

If both these program concepts offered opportunities to bridge the parent-child divide, a major technological innovation began the move toward more isolated and fragmented viewing habits that are so much a part of twenty-first-century leisure activities. In the fifties most television sets had been bulky and seldom-moved pieces of furniture as much as entertainment appliances. Late in the decade, portable televisions were introduced that could be moved from room to room on a wheeled cart or carried with some difficulty. In 1963 General Electric introduced a “personal portable” television, essentially an array of tubes encased in a lightweight plastic shell, which weighed about ten pounds and sold for $99. The new sets were colorful, relatively durable, and easily transportable, and quickly became a popular gift to children and teenagers, who could now watch their own choice of programs relatively free of adult supervision or decision-making. Yet the fifties tradition of family television viewing was not immediately broken, and for the near term Boomer kids seemed to slide effortlessly between the larger-screen (and, increasingly) color television in the living room or family room and the privacy of the new portable models.

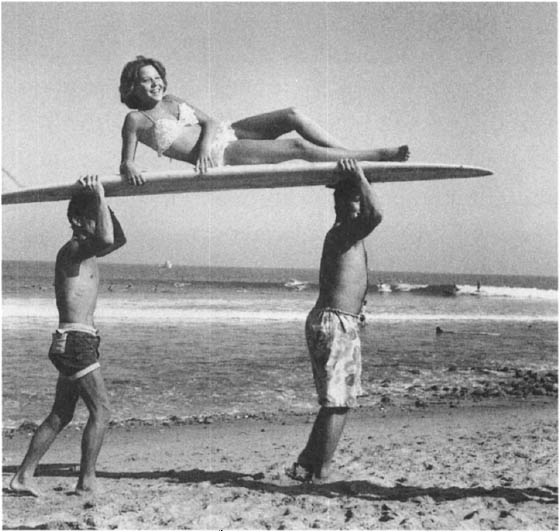

Just as television viewing habits seemed to straddle two eras during the Kennedy years, the films watched by young people during this era looked backward and forward in their cultural impact. As noted earlier, teen horror and juvenile delinquency films largely peaked in the mid-to-late fifties and then rapidly disappeared in favor of new concepts. On the one hand, the films produced primarily for adolescent or preteen audiences in the early sixties demonstrate a trend away from young people as threats to society and more toward mildly comical adventures. This era produced the beginning of the “surf” trend, with teen heartthrobs Sandra Dee and James Darren initiating the Gidget series, and Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon countering with the Beach Party series. By this time, switchblades and leather jackets (in black and white) had given way to surfboards and skis (in color) as adults ranging from meddling parents to curious college professors looked on in bemusement at the sometimes incomprehensible antics of the young generation.

While the shift of film teens from gang wars to surfing tournaments was probably a net gain for parental piece of mind, the trend in horror films clearly increased adult concern about influences on their children’s behavior. The teen horror films of the fifties had been modestly violent but, in perspective, probably no more violent than the Westerns of that era. By the early sixties young people were temporarily supplanted as the focus of horror, but the plots, still often watched by young audiences, were far more disturbing. Two Alfred Hitchcock films released during the Kennedy era made the earlier teen horror films look mild by comparison and initiated a still controversial trend in youth viewing habits. Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho shocked audiences with its famous “shower scene,” in which Janet Leigh’s character is slashed to death by a psychotic motel manager played by Anthony Perkins. While the film attracted far more adult patrons than the teen horror movies, a good many young people viewed this genesis of the “slasher” genre. Three years later Hitchcock added a new dimension with The Birds. Filmed in color, it heightened the shock effect, replacing the single slasher scene with repeated bloody confrontations between malevolent birds and largely helpless humans. In one scene youngsters are savagely attacked at a birthday party, in another scene outside their classroom, and an eleven-year-old girl becomes a focal point for the terror as the threat heightens. While neither of these films offered the pessimistic vision of young people depicted in the fifties, their style served as a gateway for the genre that would concern parents and teachers for the foreseeable future.

The southern California youth culture, centered on surfing, cars, and high school sports rivalries, proved to be easily transportable to many parts of America far from an ocean, and made stars of California’s Beach Boys. (Michael Ochs Archives/CORBIS)

While a substantial number of television programs and motion pictures were clearly made with a Boomer audience in mind, much of the music industry was also concentrating on young people as its primary customers. Adult music enthusiasts still enjoyed dominance in prime-time television programs such as the Perry Como Show and the Lawrence Welk Show, and long-playing stereo albums commanded a majority of adult sales until later in the decade. But the targeted audience for the enormously popular “singles” format was now primarily Boomers while the rock-and-roll format preferred by this age group was becoming more sophisticated and sometimes inviting adults to join the fun.

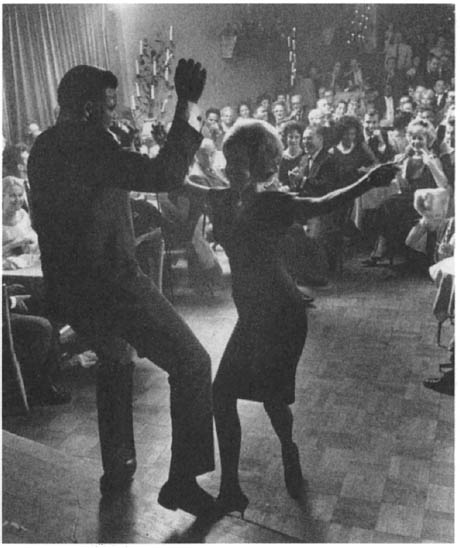

As John Kennedy was settling into the White House, a new music craze was firmly drawing a line between the fifties and the sixties, and persuading more than a few adults that rock music was not as threatening as they initially believed. A few months earlier a young South Philadelphia teenager named Ernest Evans had released a record called “The Twist” under the name of Chubby Checker. Beyond the catchy music, this new dance released listeners from the rules of couples’ or line dancing and essentially made each person on the dance floor a free agent. Dancers on American Bandstand quickly adapted to the Twist, and soon very adult nightclubbers at trendy New York venues such as the Peppermint Lounge discovered that this was the first rock-and-roll format that could be adapted to older dancers—a reality made even more exciting by the emergence of women’s fashions designed primarily for an evening of carefree Twisting. As this form of early-sixties rock and roll attracted a new, older audience that had previously rejected the music, other new trends solidified the preteen and adolescent Boomer audience that had initially been the target of the novelty tunes and teen idols of the late fifties.

A number of print, television, or motion picture chronicles of the sixties have emphasized the role of the Beatles and other British bands in “rescuing” a dying American popular music scene that had begun to unravel with the death or retirement of numerous rock pioneers. A closer examination of the period reveals that rock and roll had already entered an exciting transformation period by late 1962 or early 1963, fully a year before most Americans had heard of Paul McCartney or John Lennon. Much of the rebirth was the result of Boomers engaged as both consumers and creators of the new music. At least three major formats are evident in 1963, and each would have an important cultural and social impact on Boomer perceptions of their childhood and their environment.

The first trend was the emergence of a more substantial feminine presence in rock and roll in the form of “girl groups,” which included both ensembles and individual performers. While fifties teenage girls had bought substantial numbers of rock-and-roll records, the music was sung almost entirely by male artists. Many hit songs were about girls but mostly concerned the triumph and tragedy of romance from a male perspective. This reality began to change in the early 1960s when a group called the Shirelles made a top hit with the haunting ballad “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?” Quickly building on that success, three young husband-and-wife teams working out of the Brill Building in New York City, and a young male alumnus of a 1950s group working out of Gold Star Studios in Los Angeles, produced a string of records that featured female singers backed by increasingly sophisticated production values.

Chubby Checker, left, became the first superstar of the sixties when he enticed adults to enter the teenage world of rock and roll through the medium of the “Twist” dance craze. (Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images)

The three couples, Gerry Geffen and Carole King, Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, and Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, and the single man, Phil Specter, engaged in friendly competition and lucrative collaborations to produce songs that often defined female Boomer adolescence yet had a pulsing, danceable beat that attracted male listeners. Enlisting female singers from a diversity of African-American, Latino, and white backgrounds, girl groups such as the Crystals, the Ronettes, and the Angels sang about a wide range of emotions, from pride in a nonconformist boyfriend (“He’s a Rebel”) to frustration with parental interference (“We’re Not Too Young to Get Married”), to the magic of meeting a potential life partner (“Today I Met the Boy I’m Going to Marry”). While often dismissed by adult critics as “teen operas,” these songs resonated so heavily with Boomer audiences that advertising executives of later decades would use songs like “Be My Baby” and “My Boyfriend’s Back” as soundtracks for numerous commercials. The catchy lyrics continued to appeal to listeners who were born long after the original recordings.

While the girl groups were recruited primarily from the Northeast, a parallel but mostly male celebration of Boomer adolescence was growing at the other end of the continent. As the sport of surfing swept California beaches in the early sixties, a surfer-musician named Dick Dale provided an instrumental background to the pounding waves and the foaming sea. By 1962 an aspiring songwriter named Brian Wilson formed a group with his two brothers, a cousin, and a family friend and began to add lyrics to the surfing saga. They called themselves the Beach Boys, and their first album, “Surfin’ Safari,” became a huge regional hit and a modest national success. In the summer of 1963 follow-up songs “Surfin’ USA” and “Surfer Girl” carried the images of the California beach scene to Boomers who had never seen the ocean. Soon vocal duo Jan and Dean’s song “Surf City,” and instrumentals such as “Wipe Out” and “Pipeline,” were hinting that the West Coast, where the suntans of endless summer and the freeways patrolled by fleets of convertibles formed an adolescent paradise, was the single most attractive place in the world to be young.

Midway between Manhattan’s Brill Building and Malibu’s beach parties, a third new kind of music was rising from the gritty streets of Detroit. Energetic entrepreneur Berry Gordy was spending the Kennedy years fashioning a music empire by forming primarily African-American groups with an appeal that would transcend race among Boomers. By 1963 the distinctive purple record label of Motown Records was a major element in most stocks of 45s as the Miracles’ “Mickey’s Monkey,” Martha and the Vandellas’ “Heat Wave,” and Stevie Wonder’s “Fingertips” became summer anthems. While these songs secured Gordy’s place as an enormously successful minority business leader, he was already busy auditioning groups such as the Temptations, the Four Tops, and the Supremes, who would form much of the soundtrack of the rest of the decade.

Thus any Boomer armed with a transistor radio in 1963 was probably unaware that a group of young men from Liverpool would be needed to “rescue” rock and roll from its imminent demise. In fact the Beatles were so excited by the American scene that their early albums consisted primarily of covers of the same songs that later chronicles would dismiss as banal or sterile. Not only were the Boomers excited about “their” music well before the Beatles’ arrival, members of their own generation were just now emerging as recognizable performers. By 1963 postwar babies such as Peggy March, Lesley Gore, and Stevie Wonder were piling up strings of hits, and Gore’s birthday lament of “It’s My Party” came from an authentic Boomer sixteen-year-old, not a young adult looking back in time.

Many Boomers recall the Kennedy era as a real-life Camelot, punctuated by music, television, and films that chronicled their passage through childhood and adolescence. But at the time, adults of the era, unaware of the looming cultural upheaval, had more mixed reviews of the new generation. A growing number of magazine articles and television specials suggested that these postwar children were growing up before they were ready to handle minimal adult responsibility. In “Boys and Girls Too Old Too Soon,” Life magazine warned that America’s preteens were rushing toward trouble as ten-to-twelve-year-old girls turned themselves out in mascara and high-style hairdos, and boys turned into party hounds. Under pressure to go steady, engaged in constant campaigns to captivate each other or be captured, young boys and girls became involved in subteen romances complete with wraparound dancing and necking. Profiling one twelve-year-old girl, Life described her as a “pocket femme fatale who can wrap a boy around her little finger and works hard at it.” She was considered representative of “a generation whose jumble of innocence and worldly wisdom is unnaturally precocious and alarming.”

Interviews with early-sixties preteens revealed that parents often considered the young relationships “cute,” or simply allowed themselves to be stampeded by the sheer numbers involved. Some women took their daughters to suburban beauty parlors to keep up with the latest coiffure while other girls routinely spent two hours with friends creating beehive hairdos. The garment industry tapped into this market with “training bras” and small-size garter belts to hold up special small-size stockings. Some newspaper advertisements enticed girls to purchase wigs so that “now you can be as glamorous as mother.”

In large families of the period, some parents who had their hands full with babies or toddlers regarded preteen dating as the least of their immediate concerns. In a period of continued low divorce rates, marriage was still viewed as the institution that guaranteed happiness and security to all, especially as it was depicted in movies, television, and romance magazines. Thus some preteens who should have had a person of their age and gender as their best friend often found themselves with a miniature husband or wife. While they needed to belong in groups, pairing often was the necessary ticket of admission to many social functions.

While preteens basked in the ingratiating attention of their “steadies” and talked incessantly on the telephone hashing over the boys and girls in their lives, the Boomers who had become the vanguard of the high school generation in the early sixties were more frequently being noted for their restlessness and anti-social behavior. By the time the high school became the exclusive domain of the postwar baby surge, otherwise peaceful suburban communities tried to cope with teenagers who lacked the black leather jackets and pompadours of the fifties juvenile delinquents but could become equally threatening in khakis and crew cuts.

The summer vacation season became a potential time of trouble as waves of Boomer teens competing for limited summer jobs pushed a growing minority of bored adolescents toward gate-crashing, vandalism, and violence. Journalists cited the almost biblical status among teens of books such as Catcher in the Rye, A Separate Peace, and Lord of the Flies, and noted that an almost tribal atmosphere was developing in the parking lots and booths of suburban restaurants as boys and girls shuttled from car to car and booth to booth with the single greeting, “Where’s the party?” As one writer observed, “Almost every high school student in the nation has access to a car, his own, his parents’ or that of a friend, while teens evade the liquor laws just as successfully as his father or grandfather dodged the Volstead Act.” Critics emphasized that while parents of earlier generations had considered themselves negligent if they did not know the whereabouts of their children at all times, in the sixties a teen could announce, in all honesty, that he was driving over to a friend’s house to watch television. He might do so, and yet, before the evening was over, he and his friend, plus others picked up along the way, might visit a drive-in restaurant, a liquor store, look in on two or three parties, and cruise twenty miles on back roads to the music of blaring radios. Unless the teen telephoned home every half-hour, his or her parents would not know the exact location of their son or daughter.

Within a few years such concerns would pale in comparison to the generational confrontations instigated by the Vietnam War and the rising counterculture. By the standards of 1968 or 1969, preteens of 1962 and high school students of 1963 seemed far less threatening and far more integrated into the overall American culture. As the final summer of the Kennedy era drifted from one sun-drenched day to another, and throngs of adoring European citizens mobbed the young president, the Boomers emerged as idols for much of the young population of the planet. American popular music, films, and television spread the nation’s ideas and values over the globe. The Boomers were the youngest citizens of a young country that, despite significant challenges, was basically rich, free, and envied. Around the globe, young people of other nations played American records, watched American television and films, spoke American slang, and copied American youth fashions in a yearning to feel, at least vicariously, in touch with their counterparts in the United States. For one last summer season in Camelot, young American boys in chinos, loafers, and madras sport shirts, and young girls in Capri pants or Bermuda shorts, tennis shoes or sandals, defined modernity and youthfulness far beyond their nation’s borders. Then, in the words of Nat “King” Cole’s last hit that season, those “Hazy, Lazy, Crazy Days of Summer” drew to an inevitable close, and the oldest Boomers entered their senior year of high school with college on the horizon for many. Before their senior year was half finished, the idolized president would be slain, and before their final college exams, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy would join John Fitzgerald Kennedy in the pantheon of recent American martyrs.