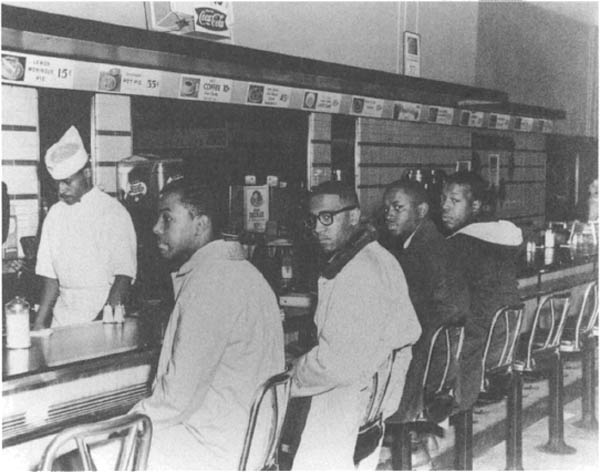

ONLY DAYS before the United States entered the decade that was to be the Soaring Sixties, Clark Kerr, president of the burgeoning University of California, appraised the students who would be attending college over the next decade: “The employers will love them. They aren’t going to press many grievances. They are going to be easy to handle. There aren’t going to be any riots.” Three thousand miles to the east, as Kerr offered his prediction, four of these “easy to handle” students were preparing the opening shot of the sixties confrontation between students and the American establishment. Ezell Blair, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond were freshmen at North Carolina A&T, an all-black college in Greensboro, North Carolina. They were attending school in a community with relatively good educational facilities for minority pupils and were welcome to spend their money in the city’s large Woolworth’s department store. But while white customers could relax from their shopping by enjoying a snack or meal at the store’s lunch counter, this foursome and other members of their race were excluded from that service. On February 1, 1960, the students left campus, headed downtown, sat down at the counter, and ordered coffee. As an astonished policeman paced behind them with no clue how to react, a few white customers cursed the students while others simply shrugged and continued shopping. A few white women even encouraged them, though the students returned to campus without their coffee. Back at school, everyone from the college dean to the student body treated them as heroes. The president of the college asked them why they had even wanted service at a counter with a reputation for tasteless food. The next day more than a dozen classmates joined them at the counter; two days later the first white student participated in the great lunch-counter sit-in while the protest idea spread outward to Durham and Winston-Salem. By Valentine’s Day college students in communities from Florida to Tennessee were crowding segregated department store lunch counters amid growing national media attention.

One of the largest and best-organized lunch-counter sitins emerged in Nashville and included Fisk University student and later civil rights leader and legislator John Lewis. As Lewis noted, “We had on that first day over five hundred students in front of Fisk University chapel to be transported downtown to the First Baptist Church, to be organized into small groups to go down to sit in at the lunch counters.

“We went into the five-and-tens, Woolworth’s, Kresge’s, and McClellan’s, because these stores were known all across the South and for the most part all across the country. We took our seats in a very orderly, peaceful fashion. The students were dressed like they were on their way to church or going to a big social affair. They had their books, and we stayed there at the lunch counter, studying and preparing our homework, because we were denied service. The managers ordered that the lunch counters be closed, that the restaurants be closed, and we’d just sit there, all day long.”

Only a few weeks after the beginning of the 1960s, students at North Carolina A&T sat in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter and demonstrated the impact of nonviolent protest against the Establishment. (Jack Moebes/CORBIS)

By mid-April seventy-eight cities in Southern and border states had become part of the sit-in movement. Fifty thousand black students and white sympathizers had participated, enduring anything from sheer boredom to vicious attacks by largely young, white townspeople. Two thousand protesters, including Lewis, were arrested as Northern counterparts threw up picket lines around stores operated by chains that were discriminating in the South. Then, as protesters confronted Nashville mayor Ben West on the steps of city hall, he admitted that discrimination at lunch counters was wrong, and six Nashville counters began serving minority customers in response.

Those first sit-ins of the sixties were organized chiefly by college students who were among the older siblings of the postwar generation. But Boomers would soon be involved in the civil rights movement, and a few of them would not even live to see college. The success of the lunch-counter sit-ins encouraged Martin Luther King to utilize nonviolent protest to end the segregation of public facilities in those parts of the Deep South where the lunch-counter campaign had made little or no impact. In 1963 Birmingham, Alabama, became the battleground in a Children’s Crusade pitting Public Safety Director Eugene “Bull” Connor, and his attack dogs and fire hoses, against Boomer teens and children as young as six.

Birmingham in 1963 was one of the most segregated cities in America with “Colored” signs over water fountains, no black police or firefighters, and a chief of public safety who had already orchestrated brutal attacks on so-called Freedom Riders attempting to integrate transportation facilities. Early in the year the jails were filling with adult demonstrators, including Dr. King, in a community that was running out of money to pay their bail. Reverend James Bevel, a veteran of the Nashville sit-ins, suggested massing huge numbers of high school students who could put pressure on the city with less of an economic threat to families if they were arrested as their parents would still be on the job. As Bevel noted, “We started organizing the prom queens of the high school, the basketball stars, the football stars, to get the influence and power leaders involved. They, in turn, got all the other students involved. The students had a community they’d been in since elementary school, so they had bonded quite well. So if one would go to jail, that had a direct effect upon another because they were classmates.”

While civil rights demonstrations were planned as peaceful protests, official response was often violent. Television images of vicious dogs attacking protesters, including children, greatly increased white sympathy for civil rights goals. (Library of Congress)

These Boomer teens were given workshops to help them overcome the fear of Bull Connor’s canine assault force and the possibility of jail life. Then they began recruiting their elementary-school-age siblings and neighbors, arguing that “Six days in Jefferson County Jail is more educational than six months in our segregated Birmingham schools.” May 2, 1963, was dubbed D-Day. As 959 six- to eight-year-old children walked out of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, Connor unleashed the dogs and fire hoses. Some of the firefighters used tripod-mounted water cannons designed to fight fires at long range with the power to knock bricks out of a wall from a hundred feet away. As small children rolled down the street under the force of this aquatic artillery, national television cameras recorded the stunning violence for evening news programs. The next day another thousand children were mobilized in the church, and Connor responded with even more attack dogs and fire hoses powerful enough to rip the bark off trees. By nightfall, city jails were filled with nearly two thousand children, and much of the nation watched in disgust as Bull Connor ensured his place in the rogues’ gallery of American folklore.

These images of unprovoked and vicious assaults on children apparently sickened President Kennedy too. His staff members organized a temporary truce in which Birmingham stores would be desegregated in exchange for a halt to the protest marches. But hard-core segregationists set off a bombing campaign that included extensive damage to the motel in which Martin Luther King was staying. Then, on September 15, 1963, eighteen days after the March on Washington, the bombers struck again. On a peaceful Sunday the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was nearly demolished by a powerful explosion. Four young girls, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins, and Cynthia Wesley, had just finished a Sunday school lesson and were in the basement changing into their choir robes. Fifteen sticks of explosives ripped through the room killing the girls, aged eleven to fourteen, and injuring twenty others as an Alabama Klan member nicknamed Dynamite Bob Chambliss watched his handiwork snuff out the young lives. The protests begun by four young students in North Carolina three years earlier had now resulted in the first child martyrs of the 1960s civil rights campaign.

While the young people who challenged the segregationist establishment generally gained at least the tacit support of many white adults, the student challenge to the university system and the American political establishment evoked much greater controversy. Almost exactly a year after the Birmingham bombing, just as the first Boomers were adapting to their freshman year in college, the academic home of the same Clark Kerr who had asserted that this college generation would be “easy” erupted in mass protest.

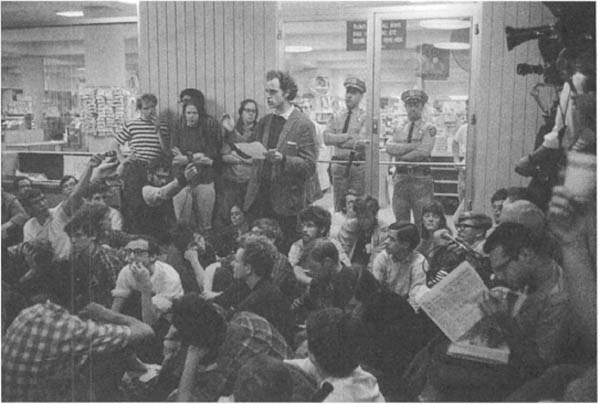

During the preceding few years University of California officials had allowed students to set up informational tables, solicit funds, and disseminate literature on an open lawn near Sproul Plaza on the Berkeley campus. At the start of the 1964 academic year, after remarks that the main entrance to the campus was crowded with “beatnik”-like activists, the administration revoked permission to congregate. Initial student protests turned into a “mill in,” in which Manhattan College transfer and recent Mississippi civil rights activist Mario Savio and several other protesters were suspended indefinitely. On October 1 a student protest against the suspensions resulted in the arrest of former student Jack Weinberg, who was escorted to a police car that was quickly surrounded by students. During a thirty-two-hour stalemate, Savio climbed on the roof of the police car to address the crowd of protesters and emerged as the leader of a burgeoning Free Speech Movement.

President Kerr offered a series of concessions to end the stand-off temporarily, but over the next two months the concessions were revoked until Kerr announced that the administrators would press charges against Savio and seven other Free Speech Movement leaders. On December 2,1964, a thousand students took over the Sproul Hall administration building and organized a “free university.” Hours later six hundred police entered the building and conducted the largest mass arrest in California history, charging eight hundred students with trespass. Many stunned faculty members declared their support for the students and for a strike they now called. On December 7 Kerr addressed a meeting of sixteen thousand faculty and students and announced a blanket clemency and liberalized policies toward student political action.

University of California student Mario Savio became the first prominent sixties student dissident when he led the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in the fall of 1964. (Bettmann/CORBIS)

Contrary to the dreams—or nightmares—of student activists and university administrators, the Berkeley uprising remained localized in the Bay Area. Yet as the first Boomer cohort arrived at the bottom of the higher-education hierarchy in that autumn of 1964, a noticeable (if difficult to measure) enthusiasm to challenge the prescribed order of things on campus was beginning to register. One of the first tremors indicating that the times were indeed changing occurred in the music entertainment and concert scene that was an important part of college social life.

Since the emergence of Elvis Presley several years earlier, a substantial segment of the college community had found rock and roll to be less than “cool” and “cerebral,” more appropriate for high schoolers and kids who did not enter higher education. The college concert and dance scene, which had been a collage of jazz, folk music, and big bands, was about to undergo a massive sea change when the first Boomers arrived.

The oldest Boomers had spent their senior year of high school entranced by the music of the Beatles and the British Invasion groups, and when they arrived in their college dorms they were little inclined to swap their music preferences for Dave Brubeck or Stan Kenton jazz. They felt quite comfortable bringing along the music of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, or the Kinks as they reached toward young adulthood. Thus Boomer freshmen began asking for their favorite rock albums in the music section of their college bookstore, wondering why the campus radio station did not play “their” music,” and clamoring for concert acts that were far less congenial to upperclassmen. No clear-cut victory would be achieved until Boomers formed the majority enrollment of each college, but it is clear that between 1964 and 1968 the college music scene was transformed from jazz to rock as a new soundtrack of the collegiate experience emerged. Along with the generational tag of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan shifted from an acoustic-guitar traditional folk singer to a more eclectic “folk rock” format, and groups such as the Byrds, the Turtles, and Sonny and Cher adapted his songs. The college Hootenanny transformed into concerts dominated by electric instruments, where audience participation songs such as “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore” became quaint artifacts of the past.

Among the skirmish points between the new students and the college administration was the continued influence of in loco parentis policies. American college administrators had traditionally assumed the role of surrogate parents for their late-adolescent charges as deans prescribed curfews, restrictions on mixed-gender socialization, and other policies they assumed parents would impose on children of this age at home. When the campuses were flooded with G.I. Bill recipients after World War II, college officials did their utmost to keep the twenty-something or even thirty-something veterans separated from their younger students. Now the Boomers were arriving at schools that often had stricter rules than those of their increasingly indulgent parents. By the mid-sixties, schools in urban areas with mixed student bodies of commuters and residents found that many of the “day hops” were teasing dorm residents about the school’s restrictions on car ownership, nightly curfews, and enforced study halls—measures that were far stricter than their parents imposed. Some male commuters found it easier to cope with the curfew expectations of a female commuter’s parents than the rigid gatekeepers positioned at the entrance to women’s residence halls. The apparently arbitrary, capricious, and sometimes mean-spirited rules of in loco parentis in sixties colleges was a major point of contention in Boomer challenges to the academic establishment, and was often the simmering issue that ignited more broad-based confrontations and demonstrations. Students of the 1950s and early 1960s seem to have reacted to stringent university policies by surreptitiously ignoring them or accepting various sanctions as the price of doing business in the student-administration “game.” Boomer students, arriving in college at a time of heightening social upheaval, found arbitrary rules simply unacceptable and were more inclined to challenge the official or system that had created them. This exasperation carried over into the sixties classroom.

Relatively fanciful books and films about the Boomer college experience in the sixties often include one or more scenes where incensed individuals or groups of students attired in “hippie-casual” clothing shout down or otherwise intimidate middle-aged professors, who are then coerced into recanting unpopular theories. This may indeed have been common in the academic chaos of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in China but would have brought gasps of shock or disbelief in the classrooms of the vast majority of American colleges during this era. Contrary to some popular depictions, the vast majority of students were polite, courteous, and deferential to their professors, even in times of heightened campus activism. Still, the Boomer classroom experience provided a degree of contention that followed from the size and interpersonal nature of many classes and a grading system that was undergoing significant change.

During the fifties and early sixties most American public colleges and some private institutions had experienced a continuing expansion of faculty and student populations. Then, in 1964, the largest high school class in history graduated. Even if schools accepted the same percentage of secondary school graduates, their enrollments would increase substantially. This growth forced some schools to build more instructional facilities or stretch the school day to include early-morning and evening classes while also putting more students in each section. More and more new classroom buildings included several huge lecture halls where hundreds of students would fill multiple tiers of desks while instructors gazed upon a sea of increasingly anonymous faces.

Just as class sizes were expanding, a number of more prestigious institutions entered a form of academic arms race in which faculty now overloaded with big classes were pressed to publish books, articles, or monographs that would improve the renown of their institutions in the academic universe. While “publish or perish” was not a new term, the concept gained intensity when even mediocre institutions had visions of improving their standing. While college administrators insisted that their students would benefit from the exciting intellectual life that was part of the scholarly process, many students saw the net result as simply a difficult-to-find instructor. More college faculty members begged off from student-adviser conferences or gratefully accepted a reduced teaching load in order to concentrate on their research. Meanwhile the institution hired less-qualified graduate assistants or teaching fellows to fill the instructional gap.

This growing instructional dilemma was coupled with a sometimes erratic grading system that left many Boomers confused and angry. Recent college grading policy had revolved around the “gentleman’s C,” where most students would receive average grades with a few excellent marks for outstanding students and a few failures for the bottom of the class—in effect, the bell curve. But surging enrollments, governmental conscription policies, and the influx of a varied instructor corps seemed to produce more confusing rules. On the one hand, state schools that were pressured by their legislatures to expand enrollment encouraged faculty to give more failing grades, producing cumulative averages that were low enough for substantial numbers of freshmen to be dismissed from school—thus reducing the strain on the institution. On the other hand, as the war in Vietnam escalated, draft deferments were based on maintaining a 2.0 or C average. If a male student’s average dropped even a fraction of a point below that level, he became eligible for military service. More than a few instructors responded to that policy, and declared their opposition to the war, by inflating grades and in some cases publicly admitting their actions. Thus the “gentleman’s C” was attacked from two opposite directions. Moreover students discovered that their grades were increasingly based on impersonal machine-scored tests, with grades posted outside departmental offices by student number instead of name.

Over the long term this confluence of forces produced a gradual grade inflation at many colleges, with corresponding rises in student expectations to the point where some twenty-first-century students would view a B or B+ as a relatively average grade and sometimes insist that an A was the only reasonable reward for a course in which they had “worked very hard,” regardless of test or assignment outcome. The Boomer students of the sixties would probably have eagerly accepted the grading standards applied to their children and grandchildren as they confronted an academic establishment that seemed to be encouraging a capricious grading system.

As Boomers became a majority and then a totality of undergraduate enrollment, challenging the academic establishment became linked to challenging the American government’s foreign and military policies. The Vietnam War defined much of the second half of the sixties and in some way affected almost every college in the United States. Support for or opposition to the conflict varied enormously from school to school and region to region, and the Boomer student attitude was almost as varied as that of the adult population. The history of young people in the sixties might have taken very different directions if the United States had avoided massive combat in Vietnam or ended the draft before the war began. The story might have been far different again if the Boomer generation had lived through the experience of World War II America. What college students faced in the sixties was a relatively limited but media-pervasive war in which there were far more eligible males than the government needed for military service but not enough volunteers to prevent the Selective Service system from occasionally dipping into the ranks of college students.

Student reaction to the Vietnam War often ignored hard facts in favor of varying degrees of “conventional wisdom.” The simple facts were that more than twenty million Boomer males turned eighteen between 1965 and 1972, and only a little more than one in ten would ever serve in Vietnam. The twelve hundred men of the Harvard class of 1968 saw only twenty-six classmates serve in Vietnam, and all returned; only two graduates of the class of 1970 reached Southeast Asia. Conscription was likely only if a student’s grade fell below the magic 2.0 line or if he could not secure a graduate school, career, or medical deferment upon graduation. Yet everyone knew students who had volunteered for Vietnam or had been drafted after losing a deferment, and some of them did die in action. For much of the war, as many students faulted President Johnson for not invading North Vietnam as supported a rapid withdrawal. Other students totally supported American war policy but adamantly opposed conscription as part of that policy.

Rather than Establishment policy separating Boomers from adults, the war much more clearly divided postwar children among themselves. By 1968 many long-term friendships had foundered on the rocks of partisan politics and related attitudes toward the war. A litmus test for anything from a first date to a steady relationship was some level of harmony over attitudes on Vietnam. Sometimes collegians who agreed on their opposition to the conflict watched enmity grow as one person supported Robert Kennedy and the other Eugene McCarthy, both anti-war presidential candidates in 1968 but each seen as the “true” candidate by one faction and a fraud by their opponents.

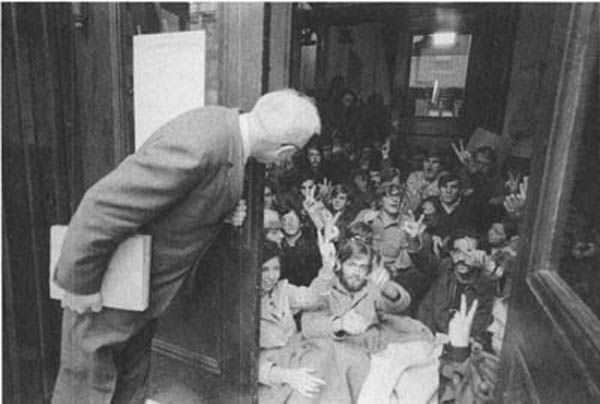

The spring of 1968 was a season of revolt and confrontation across American campuses. Two hundred major demonstrations greeted the change of seasons, but the college that became the scene of the highest-profile media event was Columbia University in New York. The Ivy League school had one of the most politically active student bodies in the nation, as nearly five hundred of the university’s three thousand undergraduates belonged to Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), a major organization of student protest. But the institution also enrolled a large number of fraternity members and was in the process of building a very good basketball team. The team’s success produced an indirect spark for a campus revolution when the board of trustees voted to replace the Lions’ tiny turn-of-the-century gym with a state-of-the-art arena to be constructed in university-owned Morningside Park. The park had been open for the use of the primarily minority population of adjoining Harlem neighborhoods, and SDS leaders saw a golden opportunity to forge an alliance with emerging black radical groups over the gymnasium issue.

On April 23, 1968, two hundred students occupied President Grayson Kirk’s office in the Lowe Library building while militant members of the Columbia Student Afro-American Society occupied Hamilton Hall and took three white administrators hostage. In effect, two parallel occupations were under way. A large number of faculty members initially backed police attempts to enter the buildings; many of their colleagues and a substantial number of non-SDS students launched counterdemonstrations against the occupation. One of the SDS organizers, James Simon Kunen, saw the revolt as alternately serious and humorous. While admitting, “We’re unhappy because of the war and because of poverty and the hopelessness of politics or because we feel lonely and alone and lost,” he also took great pleasure in shaving with the president’s razor and using his after-shave lotion and toothpaste, and regularly slipped out of Kirk’s office to get the latest baseball scores.

The student revolt at Columbia University in the spring of 1968 was the most prominent event in a tumultuous year of youthful challenges to the adult Establishment. Similar confrontations in France, Germany, and Mexico added an international dimension to the generation gap. (Bettmann/CORBIS)

The national media, however, saw little humor in a violent uprising in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King a few weeks earlier. Life magazine called it “A Great University Under Siege,” observing that “Students have usurped the seat of power at Columbia University through a six-day uprising as, with the brashness of a victorious banana republic revolutionary, the mustachioed undergraduates sat in the chair of the University President and puffed on expropriated cigars. For six turbulent days the university was effectively out of business.”

As supporters attempted to supply the occupiers with food and supplies, fraternity members, athletes, and others attempted to block their way. When occupation sympathizers attempted to throw food bags up toward the windows of the buildings under siege, opponents used “an improvised air defense system” of trash can lids to bring the parcels crashing to the ground. A proliferation of armbands seemed to illustrate hardening attitudes: orange among supporters, blue among opponents, green among neutral advocates of amnesty. A campus statue of Rodin’s The Thinker soon was outfitted in all three colors as one writer suggested, “He looked as if even he was having a hard time making up his mind.”

After Columbia’s president sent police into the occupied buildings to clear out the students, and then dropped all charges against them, television and print media began a frenzied chronicle of student challenges to the Establishment, now increasingly labeled the “generation gap.” As one writer observed, “These days the more we talk, the more we know we’re a generation apart on almost everything. We’re fascinated with the problem of how to get through to each other.”

Although attitudes toward the Vietnam War were often based more on geographical location, family background, or academic major than on age, the “generation gap” itself was not necessarily a myth. Even students who differed violently on the war often agreed that they knew more about many issues than their frequently less-educated parents. Unlike twenty-first-century college students, who more often than not come from homes with college-educated parents, a startlingly high percentage of Boomer college students in the sixties had parents who had not even graduated from high school—a sure setting for heated dinner-table conversations. Most Boomers never occupied a campus building or were booked on police charges. Yet many of these young people looked at increasingly outdated Establishment rules and insisted that now was the time for reform. Amazingly, as Boomers pressed for change, authorities often backtracked, compromised, or waffled, setting up a future round of demands.

During the frigid, snowy winter of 1968–1969, female students in a prestigious suburban Philadelphia middle school confronted an uncomfortable reality in the sixties fashion revolution. School policy called for skirts or dresses, at a time when the mini-skirt was at the peak of popularity. As the school turned down thermostats to save energy, young women would enter the classrooms to sit on frigid plastic seats. A large number of these girls had older siblings in college, many of whom advised them to choose a day when every girl would wear pants, on the assumption that the authorities would not suspend all of them. On the appointed day, the vast majority took this advice and left their skirts at home. The principal initially balked but then conceded that, due to the cold weather, young ladies could wear pants as long as they were not jeans. For a time the victorious students happily complied. Then, several months later, a few girls wore “dressy” jeans. The remainder of the story is predictable. Challenging the Establishment in the sixties could mean anything from Jim Crow bars to a war in Southeast Asia to a seemingly capricious and outdated dress code. Yet if Boomer kids frequently argued over issues and tactics, virtually an entire generation agreed that “The Times They Are A-Changin’ ” was a theme song they had in common.

This questioning would produce, in the short term, an escalating level of confrontation and violence. Only a year after the “summer of love” in San Francisco extolled the virtues of peace and harmony, enraged young people and angry police officers engaged in bloody skirmishes for control of Chicago’s Grant Park, which became the violent backdrop of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. As the haze of marijuana had wafted over Haight-Ashbury the summer before, the even more pungent odor of tear gas emerged as the sensory memory of Chicago. Yet if tolerance was at a premium that summer when racial and political epithets crisscrossed the bleeding nation, a new tolerance was just beginning to emerge behind the scenes. Soon white students at newly integrated Southern state universities would be lustily cheering black football and basketball players to defeat the real “adversary,” their rival schools. A progression of African-American-dominated music, from soul to rap to hip-hop, would enter mainstream culture and become the music of choice for large numbers of white teens. Americans of color would move from fringe roles in television and motion pictures to a dominant presence that would rival white actors. By the early twenty-first century, star power was largely colorblind, as for most young people plot and action trumped the racial or ethnic backgrounds of the stars.

The challenge to the Establishment that reached a crescendo of violence in Grant Park in the summer of 1968 would reach a far more peaceful and momentous climax four decades later in exactly the same location. On an unseasonably warm night in November 2008, an enormous crowd occupied Grant Park. Yet this time police officers merely acknowledged the people with smiles and waves. Unlike in 1968, the participants represented a wide range of Americans, from tiny infants to citizens who had already been middle-aged forty years earlier. African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and whites mixed easily, their most visible commonality being campaign buttons supporting a candidate for the American presidency. Then, after a momentary hush at 10 P.M. Central Time, a twenty-four-hour television satellite news channel (a media venue that would have been almost unthinkable forty years earlier) projected that the candidate favored by these onlookers had effectively won the presidency. The rock throwing and clubbing of 1968 were replaced by warm embraces, which included many of the men and women in blue. Finally, in the last hours of that momentous November 4, a rather young man who had known the sixties only as a child harkened back to the positive accomplishments of that tumultuous decade as he made his first speech as the newly elected president of a nation that had begun to grow more tolerant and accepting in the Boomer era.