“Did its mothers make it up a Beds then!” cried Miss Slowboy to the Baby; “and did its hair grow brown and curly, when its caps was lifted off, and frighten it, a precious Pets, a-sitting by the fires!”

With that unaccountable attraction of the mind to trifles, which is often incidental to a state of doubt and confusion, the Carrier, as he walked slowly to and fro, found himself mentally repeating even these absurd words, many times. So many times that he got them by heart, and was still conning them over and over, like a lesson, when Tilly, after administering as much friction to the little bald head with her hand as she thought wholesome (according to the practice of nurses), had once more tied the Baby’s cap on.

“And frighten it, a precious Pets, a-sitting by the fires. What frightened Dot, I wonder!” mused the Carrier, pacing to and fro.

Here the resolution (change of dress) is presented, but not recognized. The incoherence of form (the plural number, etc.) serves as the motivation for the non-recognition.

Dickens and the Mystery Novel 135

On the stage and in the novel, it is the usual practice, indeed, it is always the practice, for the secret or recognition to be first alluded to in the form of a hint. For example, in Our Mutual Friend, the presence of the Boffin couple at the wedding of John Harmon and Bella is intimated by Dickens when he speaks of,a certain noise in the annex to the church.

It is the custom in the theater for the man who has had a change of dress to reveal himself first to the audience and only then to the stage characters. Very curious indeed is Chaplin’s reversal of this device.

A crowd of people had been waiting for his appearance on stage, where he had promised to perform. One of the acts on the program called for a young man in tails to read a certain banal poem. A certain gentleman read the poem with impeccable taste and aplomb. Only when he turned his back to the audience and moved off stage, shuffling his feet in his inimitable way, did the audience recognize Chaplin.

This is very much analogous to the device of the spurious resolution. A resolution is offered in the conversation carried on between John, who is in love with Dorrit, and Clennam, who has landed in debtors’ prison. Chapter 27 (book 2), ‘‘The Pupil of the Marshalsea”;

“Mr. Clennam, do you mean to say that you don’t know?”

“What, .John?”

“Lord,” said Young John, appealing with a gasp to the spikes on the wall. “He says. What!”

Clennam looked at the spikes, and looked at John; and looked at the spikes, and looked at John.

“He says What! And what is more,” exclaimed Young John, surveying him in a doleful maze, “he appears to mean it! Do you see this window, sir?”

“Of course, I see this window.”

“See this room?”

“Why, of course I see this room.”

“That wall opposite, and that yard down below? They have all been witnesses of it, from day to day, from night to night, from week to week, from month to month. For, how often have I seen Miss Dorrit here when she has not seen me!” “Witnesses of what?” said Clennam.

“Of Miss Dorrit’s love.”

“For whom?”

“You,” said John.

But the semantic resolution does not yet unlock the verbal riddle:

The equation: Dorrit-Clennam (little woman-shadow) has not yet been solved. The “shadow” theme reappears in the words of Maggy.

Love has been openly declared, but Clennam rejects it. The inequality between them (as in the case of Eugene Onegin-Tatiana) has tilted in favor of Dorrit:

Maggy, who had fallen into very low spirits, here cried, “Oh get him into a hospital; do get him into a hospital. Mother! He’ll never look like hisself again, if he an’t got into a hospital. And then the little woman as was laways a-spinning at her

136 Theory of Prose

wheel, she can go to the cupboard with the Princess and say, what do you keep the Chicking there for? (book 2, chap. 29)

Here the theme is complicated by Dickens’s introduction of Maggy’s delirium (she had been undergoing treatment in the hospital, and both the hospital and the chickens are her paradise). A similar device is used in The Cricket on the Hearth.

The resolution of the plot line, which may be called “The Love of Arthur and Dorrit and the Obstacles to Their Marriage,” is presented, as you can see, in a rather trivial way by means of Merdle’s secret. Old Man Dorrit had entrusted his entire fortune to this Merdle, and now Little Dorrit is ruined. And so by means of this turn of events their positions in society have become equal. And herein lies the resolution. What still remains to be solved is the framing mystery of the watch.

In Turgenev’s A Nest of the Gentry, the inequality is expressed in the following way: Lavretsky cannot love Liza, because he's already married. He is released from his vows by the newspaper’s report of his wife’s death. His wife’s return (the rumor of her death was false) restores the complication to the plot. Since the composition is not resolved, a spurious ending is required. An ending is spurious, in my opinion, when it introduces a new concluding motif as a parallel to the old one. The spurious ending of A Nest of the Gentry lies in the fact that Lavretsky is sitting on a bench, while “the young tribe is growing up.”

In the case of Knut Hamsun, failure at love is presented entirely within the context of a psychological motivation. Lieutenant Glahn and Edvarda in Pan truly love each other, but whenever one says “yes,” the other says “no.” I do not mean to say, of course, that Hamsun’s motivation or even that his entire composition is superior or more expertly done than that of Ariostovsky or Pushkin. It is simply different. Perhaps Hamsun’s device will appear ludicrous with the years. Just as today, for instance, the attempt on the part of certain artists of the nineteenth century to conceal their technique appears equally odd to us.

The Relationship among Members of a Parallelism As a Mystery

The device of several simultaneous planes of action, the relationship among which is not given immediately by the author, may be understood as a complication, as a peculiar continuation of the technique of the mystery.

So begins Little Dorrit. We are immediately confronted by two plot lines in this novel, the line of Rigaud and the line of Clennam, each of which is developed into a full chapter.

In the first chapter, entitled “Sun and Shadow,” we encounter Mr. Rigaud and the Italian John Baptist. They are in prison—Rigaud on a

Dickens and the Mystery Novel 137

charge of murder and John for smuggling. Rigaud is led out to face trial. The crowd, gathered around the prison house, is in an uproar and wants to tear him to pieces. Like his prison-mate, Rigaud himself is not a principal character in the novel.

This manner of beginning a novel with a minor character instead of with the chief protagonist is quite common in Dickens, and can be found in Nicholas Nickleby, Oliver Twist, Our Mutual Friend, and Martin Chuzzlewit.

Perhaps this device is connected with the technique of the riddle.

The second group of characters is given in the second chapter, entitled “Fellow-Travellers.” This chapter is connected with the first chapter by the following phrase: “ ‘No more of yesterday’s howling, over yonder, to-day, sir; is there?’ ”

Little Dorrit is a novel built on multiple levels. In order to connect these various planes, it was necessary for Dickens to connect the protagonists in some contrived way at the outset of the novel. Dickens selects for this purpose a place of quarantine. This quarantine corresponds to the tavern or monastery of story anthologies (see the Heptameron of Margaret of Navarre and the inn in The Canterbury Tales). At this quarantine we find gathered together Mr. and Mrs. Meagles, their daughter Minnie (Pet) and the servant Tattycoram (her story is about to be told), Mr. Clennam and Miss Wade.

The same holds for Our Mutual Friend. We have before us the first chapter, entitled “On the Look-out.” Dickens introduces us here to Gaffer and to his daughter, who are towing a corpse attached to their boat. This chapter makes use of the device of the mystery, that is, we do not know precisely what these people on the boat are searching for, and the description of the corpse is presented obliquely:

Lizzie shot ahead, and the other boat fell astern. Lizzie’s father, composing himself into the easy attitude of one who had asserted the high moralities and taken an unassailable position, slowly lighted a pipe, and smoked, and took a survey of what he had in tow. What he had in tow lunged itself at him sometimes in an awful manner when the boat was checked, and sometimes seemed to try to wrench itself away, though for the most part it followed submissively. A neophyte might have fancied that the ripples passing over it were dreadfully like faint changes of expression on a sightless face; but Gaffer was no neophyte, and had no fancies.

It is worth comparing this description with the fishing scene in^ Tale of Two Cities.

In the second chapter, “The Man from Somewhere,” Dickens describes the home of the Veneerings and introduces us to the attorney Mortimer and to a whole social circle, which serves as a Greek chorus throughout the novel. Anna Pavlovna’s salon does the same for War and Peace.

At the end of the second chapter, we discover its connection with the first: we discover that a certain person who is heir to a huge fortune has drowned.

138 Theory of Prose

and we therefore connect his fate with the corpse towed by the boat.

In the third chapter, entitled “Another Man,” Dickens introduces a new character by the name of Julius Handford. In the fifth chapter he brings in the Boffin family, and in the sixth chapter the Wilfer family. These plot lines are maintained all the way to the end of the novel, and they do not so much Intersect as occasionally touch each other.

The plot lines of/I Tale of Two Cities intersect even less. We perceive in this novel a transition from one plot line to another that is evidently foreign to it, as if it were a kind of riddle. The identification of the characters of the various plot lines is deferred to the middle of the novel.

At the present time, we’re on the eve of a revival of the mystery novel. Interest in complex and entangling plot structures has grown greatly. For an example of a peculiarly distorted technique of the mystery, let us look at Andrei Bely.

It is interesting to observe in Andrei Bely a novel reincarnation of the technique of the riddle. I shall limit myself here to an example from Kotik Letaev.

This work presents the two planes of “swarm” and “form.” While “swarm” stands for the effervescent coming-\nio-hQ\ng of life, “form” stands for the actual life that has already “come into being.”

This swarm is formed either by a series of metaphor leitmotivs or by puns. We begin first with swarm and proceed on to form, that is, we’re dealing here with an inversion. The pun is presented as a riddle. At times we also find in Bely the technique of the mystery in its pure form.

See for example, “The Lion”:

Among the strangest illusions which have passed like a haze before my eyes, the strangest one of all is the following: a shaggy mug of a lion looms before me, as the howling hour strikes. I see before me yellow mouths of sand, from which a rough woolen coat is calmly looking at me. And then I see a face, and a shout is heard: “Lion is coming.”

In this strange incident, all of the sullenly flowing images are condensed for the first time: like a shaft of light, illuminating my labyrinths, they cut through the illusoriness of the darkness that had loomed over me. In the midst of the yellow areas of sunlight I recognize myself. It’s a circle; along its edges are benches; on them are dark images of women, like the images of night. It’s nannies, and around them in the light are children, hands clasped to the dark hems of their dresses. There is a curiosity of many noses in the air, and in midst of it all there is Lion. (Subsequently, I saw the yellow circle of sand between Arbat and Dog Square, and to this day you will see a circle of greenery, as you pass from Dog Square. You’ll see nannies sitting in silence while children frolic all over the place.)

This is Bely’s first hint of a resolution. Lion’s image appears once again: “The huge head of a wild beast, a lion, starts crawling towards us from one circle of light to another. And once again everything has disappeared.”

And now the resolution. Twenty years later, the author is talking to a friend at the university:

Dickens and the Mystery Novel 139

“I am describing my childhood: the old woman and the reptilian monsters. I am speaking of the little circle and of the lion and of his yellow mug..

“Come on, now. This lion’s mug of yours is pure fantasy.” My friend laughs.

“Well, yes. It was a dream.”

“No, it’s not a dream. It’s a fantasy. It’s a cock and bull story .. .”

“But I did see this in a dream,” I insisted.

“The point is that you didn't have the dream. What you saw, simply, was a St. Bernard.”

“No, I saw ‘Lion,’ ” I insisted again.

“Well, all right, so you saw a lion. But don’t you mean Lion, the St. Bernard?” my friend pressed on.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“ I remember Lion. I remember that yellow mug ... It wasn’t a lion, but a dog,” he hesitated. “Your lion’s mug was a fantasy,” he launched on an explanation. “It belonged to a St. Bernard by the name of Lion.”

“But how do you know?” I asked.

“When I was a child,” he recollected, “I used to live around Dog Square. They used to take me for a walk. There I saw Lion. ... He was a good, kind dog. Sometimes he would run onto the playground, carrying a stick in his mouth. We were afraid of him and ran in all directions, screaming.”

“And do you remember that shout, ‘Lion is coming’?”

“Of course I do.”

Later, Bely confirms the mystical sense of “Lion.” That device is also not so extraordinary.

Bely commonly states the metaphorical or the fantastic leitmotiv after first bringing out the story line.

Sometimes this is followed by a second, definitive resolution.

Let me illustrate with two examples from Turgenev.

The resolutions of “Clara Milich” are constructed along the first type (a lock of hair in the hand): this is an irreducible remnant. The denouement’s self denial.

The second case is represented by “Knock! Knock! Knock!” The first riddle of the “knock” is explained, but the riddle of the “name” remains unsolved.*

In Andrei Bely, we are dealing with the technique of the mystery in its purest form, as for example, in his St. Petersburg.

In the successors and imitators of Bely, particularly in Boris Pilnyak, we find the device of parallelism widely employed. However in this type of parallelism the relationship between the parallel planes is toned down and/ or suppressed. These novels produce an impression of complex structure,

*One of the protagonists has heard someone’s voice calling him. Then follows a second resolution, where Ilya, the peddler, a namesake of the protagonist, hears the voice of his girlfriend calling him from the kitchen garden, i.e., the mysterious “call” to Ilya, the officer now dead, from the woman he had once jilted, turns out to be pure fantasy. [Trans, note]

140 Theory of Prose

while in fact they’re quite elementary. The relationship among the parts is presented either through the most elementary of devices (the kinship bond among the leading characters) or through an episodic participation of a leading character of one plane in the action of another plane. See “A Tale of Petersburg,” “Ryazan-Apple,” “The Blizzard.” It is interesting to follow in Pilnyak the coalescence of the individual stories into a novel.

I am planning to write a separate work concerning contemporary Russian prose, and at this point I wish only to assert that in all probability the technique of the mystery will occupy an outstanding role in the novel of the future, since it already has made deep inroads into those novels that are constructed on the principle of parallelism.

The interest in plot keeps growing. The time when a Leo Tolstoi could begin a story with the device of death (“The Death of Ivan Ilyich”) and not tell the reader “what happens next” is evidently over.

Tolstoi himself loved the works of Alexandre Dumas and understood the business of plot very well indeed, but his literary orientation was elsewhere.

In the mystery novel, the solution is as important as the riddle itself.

The riddle makes it possible for the writer to manipulate the exposition, to enstrange it, to capture the reader’s attention. The main thing is not to allow the reader to find out what is in fact going on, because, once recognized, such a situation loses its horror. For this reason, in Maturin’s novel Melmoth the Wanderer, we are kept in the dark throughout the exposition about Melmoth’s secret proposals to various people in dire straits: to prisoners of the Inquisition, to people who, to stave off death from starvation, sell their own blood, to inmates of an insane asylum, to people who had strayed into subterranean caves, and so on. Every time the action approaches the actual moment of the proposal, the text comes to an abrupt halt (the novel consists of several sections, confusedly connected with each other).

For many novelists, the duty of solving the mystery is a burdensome tradition, but for the most part they do not resort to fantastic resolutions. If fantasy is introduced, then it is only at the very end, as the denouement unravels. The fantastic is then presented as a direct or, on rare occasions, as an attendant cause of the action. And, if so, then in a special form, for example, as a prediction that permits the novel to develop against the backdrop of a necessity thus posited.

We encounter the device of the fantastic in Lewis’s The Monk. Among its protagonists are a devil accompanied by a lieutenant spirit and the apparition of a nun. In the last part of the book, the devil carries off the monk and reveals the entire intrigue to him.

This revelation of the intrigue is no accident in the novel. With his complex plot structures, not unraveled by action, Dickens has recourse all the time to these devices.

Thus is the secret of the watch exposed in Little Dorrit. In addition, it is

Dickens and the Mystery Novel 141

again very typical that in order to elucidate it, Dickens gathers everyone in one room. This device is common to many novelists and has been parodied by Veniamin Kaverin in his “The Chronicle of the City of Leipzig for the Year 18—.“

In Dickens, the protagonists are brought together quite literally against their will. So, for example, Rigaud is dragged before Clennam’s mother, Pancks and John Baptist in chapter 30 (book 2), “Closing In“:

“And now,” said Mr. Pancks, whose eye had often stealthily wandered to the window-seat, and the stocking that was being mended there, “I’ve only one other word to say before I go. If Mr. Clennam was here—but unfortunately, though he has so far got the better of this fine gentleman as to return him to this place against his will, he is ill and in prison—ill and in prison, poor fellow—if he was here,” said Mr. Pancks, taking one step aside towards the window-seat, and laying his right hand upon the stocking; “he would say, ‘AfFery, tell your dreams!’ ”

The denouement is brought about by having AfFery tell her dreams. Dreams are a new ironic motivation with an enstrangement of the old device of eavesdropping.

In Dickens, eavesdropping is carried on by clerks {Nicholas Nickleby), and occasionally by the leading characters.

In Dostoevsky’s The Adolescent, eavesdropping is presented as fortuitous. This is a renewal of the device.

The artificiality of the denouement in Little Dorrit lies in this, that it takes place without any outside witnesses. Characters tell each other what they already know all too well. We cannot consider AfFery to be an audience for the other characters.

The denouement in Our Mutual Friend is more successfully organized. Again, everyone is brought together here. They all reveal a secret, the secret of the bottle. They throw Wegg out, and then they tell the story to John Harmon’s wife all over again from the beginning.

The denouement of Martin Chuzzlewit is similarly organized. All the leading characters are assembled. Old man Martin (a hoaxer and director of his own novel) explains all the riddles he himself has been responsible for.

Let me now present the denouement of Little Dorrit, also from chapter 30, “Closing In”:

The determined voice of Mrs. Clennam echoed “Stop!” Jeremiah had stopped already.

“It is closing in, Flintwinch.”

The process of disposing of the riddles now begins.

First of all, we do not know what Rigaud needs from Clennam’s house and why he had disappeared when he did, forcing everybody to search for him. It turns out that he had a secret, imposed a price on the secret, and when he was not paid for it he left the household for purposes of blackmail.

Rigaud takes Mrs. Clennam by the wrist and tells her the secret about a

142 Theory of Prose

certain house. Unfortunately, Rigaud’s story and Mrs. Clennam’s revelation of the secrets of the house take approximately twenty-four pages of printed text and cannot be quoted in their entirety.

Mrs. Clennam’s story is motivated by the fact that she does not want to hear her story from the mouth of a scoundrel.

Let me now turn to the analysis of the denouement.

First to be resolved are the dreams of Mrs. Flintwinch.

Rigaud tells the story of “a certain strange marriage, a certain strange mother,” and so on.

Flintwinch is interrupted by Affery:

“Jeremiah, keep off from me! I’ve heerd in my dreams, of Arthur’s father and his uncle. He’s a-talking of them. It was before my time here; but I’ve heerd in my dreams that Arthur’s father was a poor, irresolute, frightened chap, who had everything but his orphan life scared out of him when he was young, and that he had no voice in the choice of his wife even, but his uncle chose her.”

Rigaud continues. A happy union is concluded .. .

“Soon, the lady makes a singular and exciting discovery. Thereupon full of anger, full of jealousy, full of vengeance, she forms—see you, madame!—a scheme of retribution, the weight of which she ingeniously forces her crushed husband to bear himself, as well as execute upon her enemy. What superior intelligence!”

“Keep off, Jeremiah!” cried the palpitating Affery, taking her apron from her mouth again. “But it was one of my dreams that you told her, when you quarrelled with her one winter evening at dusk—there she sits and you looking at her—that she oughtn’t to have let Arthur when he came home, suspect his father only; . . .”

You see now the technique of interruption. Several secrets are woven together into one and resolved as one.

Mrs. Clennam speaks first. It turns out that Arthur is not her son, but the son of her husband’s mistress. The mystery of the watch is revealed:

She turned the watch upon the table, and opened it, and, with an unsoftening face, looked at the worked letters within.

“They did not forget.”

She “did not forget.”

Simultaneously Little Dorrit’s secret is revealed.

It turns out that the watch was sent to Mrs. Clennam as a reminder. Arthur’s father’s uncle repented on his deathbed and left, Rigaud says, “ ‘One thousand guineas to the little beauty you slowly hunted to death. One thousand guineas to the youngest daughter her patron might have at fifty, or (if he had none) brother’s youngest daughter, on her coming of age,. ..’ ”

This brother was Frederick Dorrit, Little Dorrit’s uncle.

I shall not continue to retell the novel and shall limit myself only to pointing out that the secret of the double is also resolved. The double turns out to be Mr. Flintwinch’s brother.

Dickens and the Mystery Novel 143

We can now make the following observations.

As you can see, Little Dorrit’s connection with Arthur’s secret is tenuous at best. She is the niece of the protector of Arthur's mother. Her participation in the secret was purely formal, and not an active one. The very will and testament was counterfeit.

The secret in essence does not form a part of the plot. It is a supplement to the plot. The question of who Arthur is is, of course, very important to Arthur, but he never finds out about it.

Chapter 34 (book 2), ‘"Gone”: Mrs. Clennam hands over to Little Dorrit documents containing information that would reveal the secret.

Little Dorrit bums them by way of her husband:

‘T want you to bum something for me.”

“Only this folded paper. If you will put it in the fire with your own hand, just as it is, my fancy will be gratified.”

“Superstitious, darling Little Dorrit? Is it a charm?”

“It is anything you like best, my own.” she answered, laughing with glistening eyes and standing on tiptoe to kiss him. “if you will only humour me when the fire bums up.” . . .

“Does the charm want any words to be said?” asked Arthur, as he held the paper over the fiame. “You can say (if you don’t mind) T love you!’ ” answered Little Dorrit. So he said it. and the paper burned away.

The secret is woven into the entire novel, but it does not serve as a basis for the action itself. In essence, it is not revealed to the one person who is most uniquely concerned with it, that is, Arthur Clennam.

In essence, what Dickens needs here is not a secret but something mysterious to slow down the action.

Rigaud’s secret is interwoven with the fundamental secret of “birth.” Rigaud is the bearer of a secret. In accordance with the author’s designs, he is involved in all the action. Yet even this is more a case of intention than realization.

Rigaud appears in the novel in the most varied situations, and it is interesting to see how Dickens emphasizes his connection with all of the leading characters.

Chapter 1 (book 2), "Fellow-Travellers”:

Throwing back his head in emptying his glass, he cast his eyes upon the travellers’ book, which lay on the piano, open, with pens and ink beside it, as if the night’s names had been registered when he was absent. Taking it in his hand, he read these entries:

What?'

William Dorrit, Esquire Frederick Dorrit, Esquire Edward Dorrit, Esquire Miss Dorrit

And suite.

From France to Italy.

Miss Amy Dorrit Mrs. General

Mr. and Mrs. Henry Gowan. From France to Italy.

144 Theory of Prose

To which he added, in a small complicated hand, ending with a long lean flourish, not unlike a lasso thrown at all the rest of the names:

Blandois. Paris. From France to Italy.

And then, with his nose coming down over his moustache, and his moustache going up under his nose, repaired to his allotted cell.

This grimace is none other than a “superscription” made by the writer.

Rigaud simply adopted a new surname. Bringing him onto the stage, the author continues each time to apply the technique of the secret in every passage of the novel. It is as if he were applying makeup to the novel. But we recognize Rigaud either by the little ditty that he had picked up in prison, “Who Passes by This Road So Late?” or by his smile. The song is introduced in the first chapter of book 1:

Who passes by this road so late?

Compagnon de la Majolaine!

Who passes by this road so late?

Always gay!

At first this song is sung by the prison-keeper to his young daughter. John Baptist joins in;

Of all the king’s knights ’tis the flower,

Compagnon de la Majolaine!

Of all the king’s knights ’tis the flower.

Always gay!

Later, this song becomes Rigaud’s song. We recognize him by it. The author has selected this song because it was “childlike” and at the same time “boastful.” The braggadocio of the content corresponds to Rigaud’s character, while the childlike character of the song, emphasized still further by the fact that it is first sung to a child, is necessary for contrast.

I fear making this analysis of the novel too exacting, of interest only to specialists. It is difficult for a nonspecialist (like myself) to illustrate the general laws of art in such minute detail. For I am not a showman but a shower.

Nonetheless, I will tell you one more detail. When Rigaud appears in his new role, the author at first shows his “secondary sign.” No one can say whether he is handsome or ugly, and it is only later that the second sign is deployed, and it is at this moment of the second sign that recognition takes place (chapter 11).

Here we see the expression of the customary law of step-by-step construction in art.

Much the same can be said for the “noises in the house.” By not allowing us time for a real resolution and confusing us with Affery’s purposefully misleading resolution, Dickens produces new details: at first, simply a noise, then in succession the noise of something fragile falling, the rustling of dry material and the “noise of something reminiscent of falling leaves”

Dickens and the Mystery Novel 145

(book 2). Subsequently, when the door fails to open, Affery offers her a false resolution: “They’re hiding someone in the house.” At the same time, though, new technical instructions are given in her own words that are very precise: . who is ... drawing lines on the wall?” This passage has to do

with a description of the cracks on the wall.

Let us return to Rigaud, whom we have forgotten in our analysis of the novel’s step-by-step construction. Rigaud himself is nothing more than a thief of documents. He is a passive bearer of a secret. He does not have “his own plot,” as does Svidrigailov, who plays a similar role in Crime and Punishment.

An even more subsidiary role is played by Miss Wade.

What is the explanation for the success of the mystery novel, from Ann Radcliffe to Dickens?

This is the way I see the matter. The adventure novel had become obsolete. It was revived by satire. There are elements of the adventure novel in Swift {Gulliver s Travels) that play a purely ancillary role in the novel.

A time of crisis followed.

Fielding parodied the old novel in Tom Jones by presenting a hero of amoral character. Instead of the traditional loyalty expressed by the lover embarking on his adventures, we witness the merry escapades of Tom Jones.

Sterne composed a parody that was even more radical. He parodied the very structure of the novel by reviewing all of its devices. Simultaneously, a new, younger generation, aspiring to canonization, began its ascent.

It was Richardson who canonized the latter. According to legend, Richardson wanted to write a new manual of letter writing but ended up writing an epistolary novel instead.

At the same time, horror stories emerge on the scene, along with the Pinkertons of that age. We also meet with Ann Radcliffe and the mystery novel (Maturin).

The old novel tried to increase the range of its devices by introducing parallel intrigues.

In order to connect several intrigues, it was found convenient to use the technique of the mystery novel.

The final result was the complex plot structures of Dickens. The mystery novel allows us to interpolate into the work large chunks of everyday life, which, while serving the purpose of impeding the action, feel the pressure of the plot and are therefore perceived as a part of the artistic whole. Thus are the descriptions of the debtors’ prison, the Circumlocution Office, and Bleeding Heart Yard incorporated into Little Dorrit. That is why the mystery novel was used as a “social novel.”

At the present time, as I’ve indicated, the mystery technique is used by such young Russian writers as Pilnyak, Slonimsky {Warsaw), and by Veniamin Kaverin. In Kaverin we witness a “Dickensian” denouement

146 Theory of Prose

with a list of all of the principal characters. However, this is not so much reminiscence as parody:

“Enough,” I said, entering, at long last, into the shop. “What nonsense are you babbling here. I can’t make heads or tails. And is there any sense in getting so excited over such a petty thing?”

I picked up a large lamp with a dark blue lampshade and lit its bright flame, so that I could look intently at those present one last time before saying good-bye.

“You’ll get what you deserve for this! you hack!” Frau Bach grumbled. “What gives you the idea that you can act as if you were at home?!”

“Pipe down, Frau Bach!” I said with full composure. “I need to say a few words to all of you before bidding farewell.”

I got up on the chair, waved my arms and said: “Attention, please!” Instantly, the faces of all present turned to me:

“Attention! This is the final chapter, my dear friends. Soon we shall have to part. I have come to love each and every one of you, and this separation shall be very hard on me. But time goes on, the plot is used up, and nothing could be more boring than to revive the statue, to turn it around, and then to marry him to the virtuous . ..”

“May I be so bold as to observe,” a stranger interrupted me, “that it would be very helpful, my dear writer, to explain a number of things first.”

“Yes?” I said, lifting my eyebrows in surprise. “Did anything seem unclear to you at the end?”

“If I may be so bold as to inquire,” the stranger continued with a courteous but cunning smile. “I mean, what about the charlatan, who. . .”

“Tsh!” I interrupted him with a cautious whisper. “Please, not a word about the charlatan. Mum is the word. In your place, my dear friend, I would have asked why the professor fell silent.”

“You threw into the envelope some kind of a poisonous drug,” said Bor.

“How silly!” I replied, “You are a tedious young man, Robert Bor. The professor fell silent, because . . .” At this very instant, Bach’s old wife put out the lamp. In the darkness I carefully climbed down from the chair, shook tenderly the hands of all present and walked out. (“The Chronicle of the City of Leipzig for the Year 18—”)

We see here the laying bare of the Dickensian device. As in the case of the English writer, all of the protagonists are brought together. It is not, however, the characters who explain the action but the author himself. What we have before us is not a denouement, as such. Instead, the device for its resolution is pointed out. There is no real denouement because the source of motivation here is parody.

Chapter 7

The Novel as Parody: Sterne’s Tristram Shandy

I do not intend in this chapter to analyze Laurence Sterne’s novel. Rather, I shall use it in order to illustrate the general laws governing plot structure. Sterne was a radical revolutionary as far as form is concerned. It was typical of him to lay bare the device. The aesthetic form is presented without any motivation whatsoever, simply as is. The difference between the conventional novel and that of Sterne is analogous to the difference between a conventional poem with sonorous instrumentation and a Futurist poem composed in transrational language {zaumnyi yazyk). Nothing has as yet been written about Sterne, or if so, then only a few trivial comments.

Upon first picking up Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, we are overwhelmed by a sense of chaos.

The action constantly breaks off, the author constantly returns to the beginning or leaps forward. The main plot, not immediately accessible, is constantly interrupted by dozens of pages filled with whimsical deliberations on the influence of a person’s nose or name on his character or else with discussions of fortifications.

The book opens, as it were, in the spirit of autobiography, but soon it is deflected from its course by a description of the hero’s birth. Nevertheless, our hero, pushed aside by material interpolated into the novel, cannot, it appears, get born.

Tristram Shandy turns into a description of one day. Let me quote Sterne himself:

I will not finish that sentence till I have made an observation upon the strange

state of affairs between the reader and myself, just as things stand at present an

observation never applicable before to any one biographical writer since the

creation of the world, but to myself and I believe will never hold good to any

other, until its final destruction and therefore, for the very novelty of it alone, it

must be worth your worships attending to.

I am this month one whole year older than I was this time twelve-month; and

having got, as you perceive, almost into the middle of my fourth volume and no

farther than to my first day’s life ’tis demonstrative that I have three hundred and

sixty-four days more life to write just now, than when I first set out; so that instead of

148 Theory of Prose

advancing, as a common writer, in my work with what I have been doing at it on

the contrary, I am just thrown so many volumes back (285-86)*

But when you examine the structure of the book more closely, you perceive first of all that this disorder is intentional. There is method to Sterne’s madness. It is as regular as a painting by Picasso.

Everything in the novel has been displaced and rearranged. The dedication to the book makes its appearance on page 25, even though it violates the three basic demands of a dedication, as regards content, form, and place.

The preface is no less unusual. It occupies nearly ten full printed pages, but it is found not in the beginning of the book but in volume 3, chapter 20, pages 192-203. The appearance of this preface is motivated by the fact that

All my heroes are off my hands; 'tis the first time I have had a moment to

spare, and I’ll make use of it, and write my preface.

Sterne pulls out all the stops in his ingenious attempt to confound the reader. As his crowning achievement, he transposes a number of chapters in Tristram Shandy chapters 18 and 19 of volume 9 come after chapter 25). This is motivated by the fact that: “All I wish is, that it may be a lesson to the world, 'to let people tell their stories their own way' ” (633).

However, the rearrangement of the chapters merely lays bare another fundamental device by Sterne which impedes the action.

At first Sterne introduces an anecdote concerning a woman who interrupts the sexual act by asking a question (5).

This anecdote is worked into the narrative as follows: Tristram Shandy’s father is intimate with his wife only on the first Sunday of every month, and we find him on that very evening winding the clock so as to get his domestic duties “out of the way at one time, and be no more plagued and pester’d with them the rest of the month” (8).

Thanks to this circumstance, an irresistible association has arisen in his wife’s mind: as soon as she hears the winding of the clock, she is immediately reminded of something different, and vice versa (20). It is precisely with the question "Pray, my dear, . . . have you not forgot to wind up the clock?" (5) that Tristram’s mother interrupts her husband’s act.

This anecdote is preceded by a general discussion on the carelessness of parents (4-5), which is followed in turn by the question posed by his mother (5), which remains unrelated to anything at this point. We’re at first under the impression that she has interrupted her husband’s speech. Sterne plays with our error:

Good G —! cried my father, making an exclamation, but taking care to moderate his voice at the same time, “Did ever woman, since the creation of the world.

*Page references are to James A. Work’s edition (Odyssey Press, 1940). Shklovsky used a Russian translation of Tristram Shandy that appeared in the journal Panteon literatury in 1892.

The Novel as Parody 149

interrupt a man with such a silly question? Pray, what was your father saying? Nothing. (5)

This is followed (5-6) by a discussion of the homunculus (fetus), spiced up with anecdotal allusions to its right of protection under the law.

It is only on pages 8-9 that we receive an explanation of the strange punctuality practiced by our hero’s father in his domestic affairs.

So, from the very beginning of the novel, we see in Tristram Shandy a displacement in time. Causes follow effects, the possibilities for false resolutions are prepared by the author himself. This is a perennial device in Sterne. The paronomastic motif of coitus, associated with a particular day, pervades the entire novel. Appearing from time to time, it serves to connect the various parts of this unusually complex masterpiece.

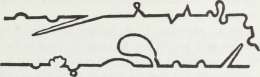

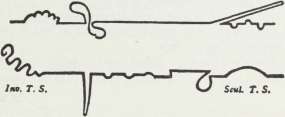

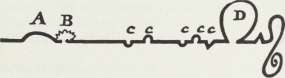

If we were to represent the matter schematically, it would take on the following form: the event itself would be symbolized by a cone, while the cause would be symbolized by its apex. In a conventional novel, such a cone is attached to the main plot line of the novel precisely by its apex. In Sterne, on the contrary, the cone is attached to the main plot line by its base. We are thus immediately thrust into a swarm of allusions and insinuations.

Such temporal transpositions are frequently met with in the poetics of the novel. Let us recall, for example, the temporal rearrangement in A Nest of the Gentry, which is motivated by Lavretsky’s reminiscence. Or then again “Oblomov’s Dream.” Similarly, we encounter temporal transpositions without motivation in Gogol’s Dead Souls (Chichikov’s childhood and Tentetnikov’s upbringing). In Sterne, however, this device pervades the entire work.

The exposition, the preparation of a given character comes only after we have already puzzled long and hard over some strange word or exclamation already uttered by this same character.

We are witnessing here a laying bare of the device. In The Belkin Tales (e.g., “The Shot”), Pushkin makes extensive use of temporal transposition. At first we see Silvio practicing at the shooting range, then we hear Silvio’s story about the unfinished duel, then we meet the count, Silvio’s adversary, and this is climaxed by the denouement. The various segments are given in the following sequence: 2-1-3. Yet this permutation is clearly motivated, while Sterne, on the contrary, lays bare the device. As I have already said, Sterne’s transposition is an end in itself:

Wlmt I have to inform you, comes, I own, a little out of its due course; for it

should have been told a hundred and fifty pages ago, but that I foresaw then ’twould come in pat hereafter, and be of more advantage here than elsewhere. (144)

In addition, Sterne lays bare the device by which he stitches the novel out of individual stories. He does so, in general, by manipulating the structure of his novel, and it is the consciousness of form through its violation that constitutes the content of the novel.

150 Theory of Prose

In my chapter on Don Quixote I have already noted several canonical devices for integrating tales into a novel.

Sterne makes use of new devices or, when using old ones, he does not conceal their conventionality. Rather, he plays with them by thrusting them to the fore.

In the conventional novel an inset story is interrupted by the main story. If the main story consists of two or more plots, then passages from them follow alternately, as in Don Quixote, where scenes of the hero’s adventures at the duke’s court alternate with scenes depicting Sancho Panza’s governorship.

Zelinsky points out something completely contrary in Homer. He never depicts two simultaneous actions. Even if the course of events demands simultaneity, still they are presented in a causal sequence. The only simultaneity possible occurs when Homer shows us one protagonist in action, while alluding to another protagonist in his inactive state.

Sterne allows for simultaneity of action, but he parodies the deployment of the plot line and the intrusion of new material into it.

In the first part of the novel we are offered, as material for development, a description of Tristram Shandy’s birth. This description occupies 276 pages, hardly any of which deals with the description of the birth itself Instead, what is developed for the most part is the conversation between the father of our hero and Uncle Toby.

This is how the development takes place:

I wonder whaf s all that noise, and running backwards and forwards for,

above stairs, quoth my father, addressing himself, after an hour and a half’s silence,

to my uncle Toby, who you must know, was sitting on the opposite side of the

fire, smoking his social pipe all the time, in mute contemplation of a new pair of

black-plush-breeches which he had got on; What can they be doing brother?

quoth my father, we can scarce hear ourselves talk.

I think, replied my uncle Toby, taking his pipe from his mouth, and striking the head of it two or three times upon the nail of his left thumb, as he began his sentence,

1 think, says he: But to enter rightly into my uncle Toby’s sentiments upon

this matter, you must be made to enter first a little into his character, the out-lines of which I shall just give you, and then the dialogue between him and my father will go on as well again. (63)

A discussion concerning inconstancy begins immediately thereafter. This discussion is so whimsical that the only way to convey it would be to literally transcribe it verbatim. On page 65 Sterne remembers: “But I forget my uncle Toby, whom all this while we have left knocking the ashes out of his tobacco pipe.”

Conversations concerning Uncle Toby, along with a brief history of Aunt Dinah follow. On page 72 Sterne remembers: “I was just going, for example, to have given you the great out-lines of my uncle Toby’s most whimsical

character; when my aunt Dinah and the coachman came a-cross us, and

led us a vagary....”

The Novel as Parody IS I

Unfortunately I cannot quote all of Sterne and shall therefore leap over a large part of the text:

. . . from the beginning of this, you see, I have constructed the main work and the adventitious parts of it with such intersections, and have so complicated and involved the digressive and progressive movements, one wheel within another, that

the whole machine, in general, has been kept a-going; and, what’s more, it shall

be kept a-going these forty years, if it pleases the fountain of health to bless me so long with life and good spirits. (73-74)

So ends chapter 22. It is followed by chapter 23: “I have a strong propensity in me to begin this chapter very nonsensically, and I will not balk my fancy. Accordingly I set off thus.”

We have before us new digressions.

On page 77 the author reminds us that: “If I was not morally sure that the reader must be out of all patience for my uncle Toby’s character,.. .”

A page later begins a description of Uncle Toby’s “Hobby-Horse” (i.e., his mania). It turns out that Uncle Toby, who was wounded in the groin at the siege of Namur, has a passion for building model fortresses. Finally, however, on page 99, Uncle Toby finishes the task he had started on page 63:

I think, replied my uncle Toby, taking, as I told you, his pipe from his mouth,

and striking the ashes out of it as he began his sentence; 1 think, replied he, it

would not be amiss, brother, if we rung the bell.

This device is constantly used by Sterne and, as is evident from his facetious reminders of Uncle Toby, he’s not only aware of the hyperbolic nature of such development but plays with it.

This method of developing the action is, as I’ve already said, the norm for Sterne. Here’s an example from page 144: “I wish,. . . you had seen what prodigious armies we had in Flanders.” This is immediately followed by a development of the material concerned with the father’s mania. The following manias are woven into the character of Tristram Shandy’s father: the subject of the harmful effect of the pressure exerted on the baby’s head by the mother’s contractions during labor (149-54), the influence of a person’s name on his character (this motif is developed in great detail), and the effect of the size of the nose on a person’s faculties (this motif is developed with unusual magnificence from page 217 on). After a brief pause begins the development of the material concerned with the curious stories about noses. Especially remarkable is the story of Slawkenbergius. Tristram’s father knows a full ten dozen stories by this man. The development of the theme of noseology concludes on page 272.

Mr. Shandy’s first mania also plays a role in this development. That is, Sterne digresses in order to speak about it. The main plot returns on page 157:

152 Theory of Prose

“I wish, Dr. Slop,” quoth my uncle Toby (repeating his wish for Dr. Slop a second time, and with a degree of more zeal and earnestness in his manner of

wishing, than he had wished it at first) “I wish. Dr. Slop,” quoth my uncle Toby,

“you had seen what prodigious armies we had in Flanders. ”

Again, the developmental material intrudes.

On page 163 we again find: “‘What prodigious armies you had in Flanders!’ ”

This conscious, exaggerated development often takes place in Sterne even without the use of a repetitive, connective phrase:

The moment my father got up into his chamber, he threw himself prostrate across his bed in the wildest disorder imaginable, but at the same time, in the most lamentable attitude of a man borne down with sorrows, that ever the eye of pity dropp’d a tear for. (215-16)

There follows a description of a bodily posture, very characteristic of Sterne:

The palm of his right hand, as he fell upon the bed, receiving his forehead, and covering the greatest part of both his eyes, gently sunk down with his head (his elbow

giving way backwards) till his nose touch’d the quilt; his left arm hung insensible

over the side of the bed, his knuckles reclining upon the handle of the chamber pot,

which peep'd out beyond the valance, his right leg (his left being drawn up

towards his body) hung half over the side of the bed, the edge of it pressing upon his shin-bone.

Mr. Shandy’s despair is called forth by the fact that the bridge of his son’s nose was crushed during delivery by the midwife’s tongs. This occasions (as I have already said) a whole epic on noses. On page 273 we return once more to the bedridden father: “My father lay stretched across the bed as still as if the hand of death had pushed him down, for a full hour and a half, before he began to play upon the floor with the toe of that foot, which hung over the bed-side.”

I cannot restrain myself from saying a few words about Sterne’s postures in general. Sterne was the first writer to introduce a description of poses into the novel. They’re always depicted by him in a strange manner, or rather they are enstranged.

Here is another example: “Brother Toby, replied my father, taking his wig from off his head with his right hand, and with his left pulling out a striped India handkerchief from his right coat pocket. . . ” (158).

Let us move right on to the next page: “It was not an easy matter in any king’s reign, (unless you were as lean a subject as myself) to have forced your hand diagonally, quite across your whole body, so as to gain the bottom of your opposite coat-pocket.”

Sterne’s method of depicting postures was inherited by Leo Tolstoi (Eikhenbaum), but in a weaker form and with a psychological motivation.

Let us now return to the development. I shall offer several examples of

The Novel as Parody 153

development in Sterne, and I shall select a case in which the device turns upon itself, so to speak, that is, where the realization of the form constitutes the content of the work:

What a chapter of chances, said my father, turning himself about upon the first

landing, as he and my uncle Toby were going down stairs what a long chapter of

chances do the events of this world lay open to us! (279)

A discussion with an erotic tinge, of which I shall speak more later;

Is it not a shame to make two chapters of what passed in going down one pair of stairs? for we are got no farther yet than to the first landing, and there are fifteen more steps down to the bottom; and for aught I know, as my father and my uncle Toby are in a talking humour, there may be as many chapters as steps. (281)

This entire chapter is dedicated by Sterne to a discussion of chapters.

Vol. 4, chap. / /.• We shall bring all things to rights, said my father, setting his foot upon the first step from the landing. . . . (283)

Chap. 12: And how does your mistress? cried my father, taking the same step

over again from the landing,.. . (284)

Chap. 13: Holla! you chairman! here’s sixpence do step into that

bookseller’s shop, and call me a day-tall critick. I am very willing to give any one of ’em a crown to help me with his tackling, to get my father and my uncle Toby off the stairs, and to put them to bed. . . .

I am this month one whole year older than I was this time twelve-month; and

having got, as you perceive, almost into the middle of my fourth volume and no

farther than to my first day’s life ’tis demonstrative that I have three hundred and

sixty-four days more life to write just now, than when I first set out; so that instead of

advancing, as a common writer, in my work with what I have been doing at it on

the contrary. I am just thrown so many volumes back. . . . (285-86)

This orientation towards form and towards the normative aspect of that form reminds us of the octaves and sonnets which were filled with nothing but a description of the fact of their composition.

I would like to add one final example of Sterne’s development:

My mother was going very gingerly in the dark along the passage which led to the

parlour, as my uncle Toby pronounced the word wife. ’Tis a shrill, penetrating

sound of itself, and Obadiah had helped it by leaving the door a little a-jar, so that my mother heard enough of it, to imagine herself the subject of the conversation; so

laying the edge of her finger across her two lips holding in her breath, and

bending her head a little downwards, with a twist of her neck (not towards the

door, but from it, by which means her ear was brought to the chink) she listened

with all her powers; the listening slave, with the Goddess of Silence at his back,

could not have given a finer thought for an intaglio.

In this attitude I am determined to let her stand for five minutes; till I bring up the affairs of the kitchen (as Rapin does those of the church) to the same period. (357-58)

154 Theory of Prose

Vol. 5, chap. 11 :1 am a Turk if I had not as much forgot my mother, as if Nature had plaistered me up, and set me down naked upon the banks of the river Nile, without one.

However, these reminders are followed again by digressions. The reminder itself is necessary only in order to renew our awareness of the “forgotten mother,” so that its development would not fade from view.

Finally, on page 370, the mother changes her posture: “Then, cried my mother, opening the door,...”

Here Sterne develops the action by resorting to a second parallel story. Instead of being presented discursively, time in such novels is thought to have come to a stop or, at least, it is no longer taken into account. Shakespeare uses inset scenes in precisely this way. Thrust into the basic action of the plot, they deflect us from the flow of time. And even if the entire inset conversation (invariably, with new characters) lasts for only a few minutes, the author considers it possible to carry on the action (presumably without lowering the proscenium curtain which in Shakespeare’s theater most likely did not exist), as if hours had passed or even an entire night (Silverswan). By mentioning them and by reminding us of the fact that his mother has been left standing bent over, Sterne fulfills the device and compels us to experience it.

It is interesting in general to study the role of time in Sterne’s works. “Literary” time is pure conventionality whose laws do not coincide with the laws of ordinary time. If we were to examine, for example, the plethora of stories and incidents packed into Don Quixote, we would perceive that the day as such hardly exists at all, since the cycle of day and night does not play a compositional role in the alternation of events. Similarly in Abbe Prevost’s narration in Manon Lescaut: the Chevalier de Grieux relates the first part of the novel in one fell swoop, and then after taking a breather, he relates the remainder. Such a conversation would last about sixteen hours, and only if the Chevalier read them through quickly.

I have already spoken about the conventionality of time onstage. In Sterne this conventionality of “literary” time is consciously utilized as material for play.

Volume 2, chapter 8:

It is about an hour and a half s tolerable good reading since my uncle Toby rung the bell, when Obadiah was order’d to saddle a horse, and go for Dr. Slop the man-

midwife; so that no one can say, with reason, that I have not allowed Obadiah

time enough, poetically speaking, and considering the emergency too, both to go and

come; tho’, morally and truly speaking, the man, perhaps, has scarce had time to

get on his boots.

If the hypercritic will go upon this; and is resolved after all to take a pendulum, and measure the true distance betwixt the ringing of the bell, and the rap at the door,

and, after finding it to be no more than two minutes, thirteen seconds, and three

fifths, should take upon him to insult over me for such a breach in the unity, or

rather probability, of time; 1 would remind him, that the idea of duration and of

The Novel as Parody 155

its simple modes, is got merely from the train and succession of our ideas, and is

the true scholastic pendulum, and by which, as a scholar, I will be tried in this

matter, abjuring and detesting the jurisdiction of all other pendulums what-

ever.

I would, therefore, desire him to consider that it is but poor eight miles from

Shandy-Hall to Dr. Slop, the man mid-wife’s house; and that whilst Obadiah

has been going those said miles and back, I have brought my uncle Toby from

Namur, quite across all Flanders, into England: That I have had him ill upon

my hands near four years; and have since travelled him and Corporal Trim,

in a chariot and four, a journey of near two hundred miles down into Yorkshire;

all which put together, must have prepared the reader’s imagination for the entrance

of Dr. Slop upon the stage, as much, at least (I hope) as a dance, a song, or a

concerto between the acts.

If my hypercritic is intractable, alledging, that two minutes and thirteen seconds

are no more than two minutes and thirteen seconds, when I have said all I can

about them; and that this plea, tho’ it might save me dramatically, will damn me

biographically, rendering my book, from this very moment, a profess’d Romance,

which, before, was a book apocryphal: If I am thus pressed 1 then put an end

to the whole objection and controversy about it all at once, by acquainting him,

that Obadiah had not got above threescore yards from the stable-yard before he met with Dr. Slop. (103-4)

From the old devices, and with hardly a change, Sterne made use of the device of the “found manuscript.” This is the way in which Yorick’s sermon is introduced into the novel. But the reading of this found manuscript does not represent a long digression from the novel and is constantly interrupted mainly by emotional outbursts. The sermon occupies pages 117-41 but it is vigorously pushed aside by Sterne’s usual interpretations.

The reading begins with a description of the corporal’s posture, as depicted with the deliberate awkwardness so typical of Sterne:

He stood before them with his body swayed, and bent forwards just so far, as to

make an angle of 85 degrees and a half upon the plain of the horizon; which

sound orators, to whom I address this, know very well, to be the true persuasive angle of incidence;. . . (122)

Later he again writes:

He stood, for I repeat it, to take the picture of him in at one view, with his body

sway’d, and somewhat bent forwards, his right leg firm under him, sustaining

seven-eighths of his whole weight, the foot of his left leg, the defect of which was

no disadvantage to his attitude, advanced a little, not laterally, nor forwards, but

in a line betwixt them; . . .

And so on. The whole description occupies more than a page. The sermon is interrupted by the story of Corporal Trim’s brother. This is followed by the dissenting theological interpolations of the Catholic listener (125, 126, 128, 129, etc.) and by Uncle Toby’s comment on fortifications (133, 134, etc.). In this way the reading of the manuscript in Sterne is far more closely linked to the novel than in Cervantes.

156 Theory of Prose

The found manuscript in SentimentalJourney became Sterne’s favorite device. In it he discovers the manuscript of Rabelais, as he supposes. The manuscript breaks off, as is typical for Sterne, for a discussion about the art of wrapping merchandise. The unfinished story is canonical for Sterne, both in its motivated as well as unmotivated forms. When the manuscript is "introduced into the novel, the break is motivated by the loss of its conclusion. The simple break which concludes Tristram Shandy is completely unmotivated:

L--d! said my mother, what is all this story about?

A COCK and a BULL, said Yorick And one of the best of its kind, I ever heard.

SentimentalJourney ends in the same way: .. So that when I stretch’d

out my hand, I caught hold of the Fille de Chambre’s—”

This is of course a definite stylistic device based on differential qualities. Sterne was writing against a background of the adventure novel with its extremely rigorous forms that demanded, among other things, that a novel end with a wedding or marriage. The forms most characteristic of Sterne are those which result from the displacement and violation of conventional forms. He acts no differently when it is time for him to conclude his novels. It is as if we fell upon them: on the staircase, for instance, in the very place where we expect to find a landing, we find instead a gaping hole. Gogol’s “Ivan Fyodorovich Shponka and His Auntie” represents just such a method of ending a story, but with a motivation: the last page of the manuscript goes for the wrapping of baked pies. (Sterne, on the other hand, uses the ending of his manuscript to wrap black currant preserves.) The notes for Hoffmann’s Kater Murr present much the same picture, with a motivated absence of the ending, but they are complicated by a temporal transposition (that is, they are motivated by the fact that the pages are in disarray) and by a parallel structure.

The tale of Le Fever is introduced by Sterne in a thoroughly traditional way. Tristram’s birth occasions a discussion concerning the choice of a tutor. Uncle Toby proposes for the role the poor son of Le Fever, and thus begins an inset tale, which is carried on in the name of the author:

Then, brother Shandy, answered my uncle Toby, raising himself off the chair, and

laying down his pipe to take hold of my father’s other hand, 1 humbly beg I may

recommend poor Le Fever’s son to you; a tear of Joy of the first water sparkled

in my uncle Toby’s eye, and another, the fellow to it, in the corporal’s as the

proposition was made; you will see why when you read Le Fever’s story:

fool that I was! nor can I recollect, (nor perhaps you) without turning back to the place, what it was that hindred me from letting the corporal tell it in his own words; but the occasion is lost, 1 must tell it now in my own. (415-16)

The tale of Le Fever now commences. It covers pages 379-95. A description of Tristram’s Journeys also represents a separate unit. It occupies pages

The Novel as Parody 157

436-93. This episode was later deployed step for step and motif for motif in Sterne’s SentimentalJourney. In the description of the journey Sterne has interpolated the story of the Abbess of Andouillets (459-65).

This heterogeneous material, weighed down as it is with long extracts from the works of a variety of pedants, would no doubt have broken the back of this novel, were it not that the novel is held together tightly by leitmotivs. A specific motif is neither developed nor realized; it is merely mentioned from time to time. Its fulfillment is deferred to a point in time which seems to be receding further and further away from us. Yet, its very presence throughout the length and breadth of the novel serves to link the episodes.

There are several such motifs. One is the motif of the knots. It appears in the following way: a sack containing Dr. Slop’s obstetrical instruments is tied in several knots:

Tis God’s mercy, quoth he 1 Dr. Slop], (to himselO that Mrs. Shandy has had so bad

a time of it, else she might have been brought to bed seven times told, before one

half of these knots could have got untied. (167)

In the case of knots, by which, in the first place, I would not be understood

to mean slip-knots, because in the course of my life and opinions, my

opinions concerning them will come in more properly when I mention. . . . (next chapter)

A discussion concerning knots and loops and bows continues ad nauseam. Meanwhile, Dr. Slop reaches for his knife and cuts the knots. Due to his carelessness, he wounds his hand. He then begins to swear, whereupon the elder Shandy, with Cervantesque seriousness, suggests that instead of carrying on in vain, he should curse in accordance with the rules of art. In his capacity as the leader. Shandy then proposes the Catholic formula of excommunication. Slop picks up the text and starts reading. The formula occupies two full pages. It is curious to observe here the motivation for the appearance of material considered necessary by Sterne for further development. This material is usually represented by works of medieval learning, which by Sterne’s time had already acquired a comical tinge. (As is true also of words pronounced by foreigners in their peculiar dialects.) This material is interspersed in Tristram’s father’s speech, and its appearance is motivated by his manias. Here, though, the motivation is more complex. Apart from the father’s role, we encounter also material concerning the infant’s baptism before his birth and the lawyers’ comical argument concerning the question of whether the mother was a relative of her own son.

The “knots” and “chambermaids” motif appears again on page 363. But then the author dismisses the idea of writing a chapter on them, proposing instead another chapter on chambermaids, green coats, and old hats. However the matter of the knots is not yet exhausted. It resurfaces at the very end on page 617 in the form of a promise to write a special chapter on them.

158 Theory of Prose

Similarly, the repeated mention of Jenny also constitutes a running motif throughout the novel. Jenny appears in the novel in the following way:

... it is no more than a week from this very day, in which I am now writing this book

for the edification of the world, which is March 9, 1759, that my dear, dear

Jenny observing I look’d a little grave, as she stood cheapening a silk of five-and-

twenty shillings a yard, told the mercer, she was sorry she had given him so

much trouble; and immediately went and bought herself a yard-wide stuff of

ten-pence a yard. (44)

On page 48 Sterne plays with the reader’s desire to know what role Jenny plays in his life:

I own the tender appellation of my dear, dear Jenny, with some other strokes

of conjugal knowledge, interspersed here and there, might, naturally enough, have misled the most candid judge in the world into such a determination against me.

All I plead for, in this case. Madam, is strict justice, and that you do so much

of it, to me as well as to yourself, as not to prejudge or receive such an impres-

sion of me, till you have better evidence, than I am positive, at present, can be

produced against me: Not that I can be so vain or unreasonable. Madam, as

to desire you should therefore think, that my dear, dear Jenny is my kept mistress;

no, that would be flattering my character in the other extream, and giving

it an air of freedom, which, perhaps, it has no kind of right to. All I contend for, is the utter impossibility for some volumes, that you, or the most penetrating spirit

upon earth, should know how this matter really stands. It is not impossible, but

that my dear, dear Jenny! tender as the appellation is, may be my child.

Consider, 1 was bom in the year eighteen. Nor is there any thing unnatural

or extravagant in the supposition, that my dear Jenny may be my friend. Friend!

My friend. Surely, Madam, a friendship between the two sexes may subsist,

and be supported without Fy! Mr. Shandy: Without any thing. Madam, but

that tender and delicious sentiment, which ever mixes in friendship, where there is a difference of sex.

The Jenny motif appears again on page 337:

I shall never get all through in five minutes, that 1 fear and the thing I hope is,

that your worships and reverences are not offended if you are, depend upon’t

I’ll give you something, my good gentry, next year, to be offended at that’s

my dear Jenny’s way but who my Jenny is and which is the right and which

the wrong end of a woman, is the thing to be concealed it will be told you the

next chapter but one, to my chapter of button-holes, and not one chapter

before.

And on page 493 we have the following passage: “I love the Pythagoreans (much more than ever I dare to tell my dear Jenny).”

We encounter another reminder on page 550 and on page 610. The latter one (I have passed over several others) is quite sentimental, a genuine rarity in Sterne:

I will not argue the matter: Time wastes too fast: every letter I trace tells me with what rapidity Life follows my pen; the days and hours of it, more precious, my dear

The Novel as Parody 159

Jenny! than the rubies about thy neck, are flying over our heads like light clouds of a

windy day, never to return more every thing presses on whilst thou art

twisting that lock, see! it grows grey; and every time I kiss thy hand to bid adieu,

and every absence which follows it, are preludes to that eternal separation which we

are shortly to make.

Heaven have mercy upon us both!

Chapter 9

Now, for what the world thinks of that ejaculation 1 would not give a groat.

This is all of chapter 9, volume 9.

It would be interesting to take up for a moment the subject of sentimentality in general. Sentimentality cannot constitute the content of art, if only for the reason that art does not have a separate content. The depiction of things from a “sentimental point of view” is a special method of depiction, very much, for example, as these things might be from the point of view of a horse (Tolstoi’s “Kholstomer”) or of a giant (Swift).

By its very essence, art is without emotion. Recall, if you will, that in fairy tales people are shoved into a barrel bristling with nails, only to be rolled down into the sea. In our version of “Tom Thumb,” a cannibal cuts off the heads of his daughters, and the children who listen rapturously to every detail of this legend never let you skip over these details during the telling and retelling of the story. This isn’t cruelty. It’s fable.

In Spring Ritual Song, Professor Anichkov presents examples of folkloric dance songs. These songs speak of a bad-tempered, querulous husband, of death, and of worms. This is tragic, yes, but only in the world of song.

In art, blood is not bloody. No, it just rhymes with “flood.” It is material either for a structure of sounds or for a structure of images. For this reason, art is pitiless or rather without pity, apart from those cases where the feeling of sympathy forms the material for the artistic structure. But even in that case, we must consider it from the point of view of the composition. Similarly, if we want to understand how a certain machine works, we examine its drive belt first. That is, we consider this detail from the standpoint of a machinist and not, for instance, from the standpoint of a vegetarian.

Of course, Sterne is also without pity. Let me offer an example. The elder Shandy’s son, Bobby, dies at precisely the moment when the father is vacillating over whether to use the money that had fallen into his hands by chance in order to send his son abroad or else to use it for improvements on the estate:

... my uncle Toby hummed over the letter.

he’s

160 Theory of Prose

gone! said my uncle Toby. Where Who? cried my father. My nephew,

said my unde T. '-^y. —What without leave without money without

governor? cried my father in amazement. No; he is dead, my dear brother, quoth

my uncle Toby. (350)

Death is here used by Sterne for the purpose of creating a “misunderstanding,” very common in a work of art when two characters are speaking at cross-purposes about, apparently, the same thing. Let us consider another example: the first conversation between the mayor and Khlestakov in Gogol’s The Inspector General

Mayor: Excuse me.

Kh.: Oh, it’s nothing.

Mayor: It is my duty, as mayor of this city, to protect all passersby and highborn folk from fleecers like you . . .

Kh. (stammering at first, then speaking loud towards the latter part of his speech): What can I-I. . . do? . . . It’s not my fault. . . I’ll pay for it, really! I’m expecting a check from home any day now. (Bobchinsky peeps from behind the door.) It’s his fault! He is to blame! You should see the beef he’s selling, as hard as a log. And that soup of his, ugh! Who knows where he dredged it up. I dumped it out of the window. Couldn’t help it. He keeps me on the very edge of starvation for days at a time . . . And while you are at it, why not get a whiff of his—ugh!—tea. Smells more like rotten fish than tea. Why the hell should I. . . It’s unheard of!

Mayor (timidly): Excuse me, sir, I’m really not to blame. The beef I sell on the market is always first class, brought into town by merchants from Kholmogorsk, sober, respectable people, if ever such existed, I assure you, sir. If only I knew where he’s been picking up such . . . But if anything is amiss, sir,. .. Permit me to transfer you to other quarters.

Kh.: No, I won’t go! I know what you mean by "other quarters”! Prison! that’s what you mean, isn’t that right! By what right? How dare you? . . . Why, I... I am in the employ of. . . in Petersburg. Do you hear? (with vigor) I, I, I. . .

Mayor (aside): Oh, my God! He is in a rage! He’s found me out. It’s those damned busybody merchants. They must have told him everything.

Kh. (bravely): I won’t go! Not even if you bring the whole police force with you! I’m going straight to the top. Yes, right up to the Prime Minister! (He pounds his fist on the table) How dare you?! How dare you?!

A/flvor (trembling all over): Have mercy, please spare me, kind sir! I have a wife and little ones. . . Don’t bring me to ruin!

Kh.: No, I won’t! No way! And what’s more! What do I care if you have a wife and kids. So I have to go to prison for their sake? Just splendid! (Bobchinsky, peeking through the door, hides in fear.) No, sirree! Thanks but no thanks!

Mavor(trembling): It’s not my fault, sir. It’s my inexperience, my God. that’s all, just plain inexperience. And, you know, I am really anything but rich. Judge for yourself: The salary of a civil servant will hardly cover tea and sugar. Well, maybe I did take some bribes. Your Excellency, but, mind you, sir, just a ruble here and there, and only o-nnce or t-wwice, if you know what I mean ... Just something for the table or maybe a dress or two. As for that NCO’s widow, who runs a shop . .. I assure, sir, I never, I assure you. Your Excellency, never stooped so low as to flog her, as some people have been saying. It’s slander, nothing but slander, fabricated

The Novel as Parody 161

by scoundrels with evil in their hearts! They would stoop to anything to do me in! I assure you, Your Noble Excellency, sir!.. .

Kh.: So what? What does all this have to do with me? .. . (reflecting) I can’t imagine why you are dragging in these scoundrels or the widow of a noncommissioned officer. .. , The NCO’s wife is one thing, but don’t you dare try to flog me. You’ll never get away with it. . . And, besides,. . . just look here! I’ll pay the bill, I assure you, sir. I’ll get the money if it kills me, but not just now. That’s why I am sitting here, because I am broke. Really, sir. I am clean broke.

Here is another example from Griboedov’s IVoe from Wit:

Zagorestsky: So Chatsky is responsible for the hubbub?

Countess Dowager: What? Chatsky has been horribly clubbed?

Zagorestsky: Went mad in the mountains from a wound in the head.

Countess Dowager: How is that? He wound up with a bounty on his head?

We see the same device used (with the same motivation of deafness) in Russian folk drama. However, because of the looser plot structure, this device is used there for the purpose of constructing a whole pattern of puns. The old grave-diggers are summoned before King Maximilian:

Max.: Go and bring me the old grave-diggers.

Footman: Yes, Your Majesty, I shall go and fetch them.

(Footman and Grave-diggers)

Footman: Are the grave-diggers home, sir?

1st Grave-digger: What do you want?

Footman: Your presence is requested by His Majesty.

1st Grave-digger: By whom? His Modesty?

Footman: No, His Majesty!

1st Grave-digger: Tell him that no one is home. Today is a holiday. We are celebrating.

Footman: Vasily Ivanovich, His Majesty wishes to reward you for your services.

1st Grave-digger: Reward me for my verses? What verses?

Footman: No! Not verses, services!

1st Grave-digger {io 2nd grave-digger): Moky!

2nd Grave-digger: What, Patrak?

1st Grave-digger: Let’s go see the king.