FROM THE “GERM-PROOF FILTER” to enduring Arts & Crafts acclaim – that’s the unlikely journey of Fulper Pottery, maker of the early 20th-century uniquely glazed artware that’s become a favorite with today’s collectors.

Fulper began life in 1814 as the Samuel Hill Pottery, named after its founder, a New Jersey potter. In its early years, the pottery specialized in useful items such as storage crocks and drain pipes fashioned from the area’s red clay. Abraham Fulper, a worker at the pottery, eventually became Hill’s partner, purchasing the company in 1860. Renamed after its new owner, Fulper Pottery continued to produce a variety of utilitarian tile and crockery. By the turn of the 20th century, the firm, now led by Abraham’s sons, introduced a line of fire-proof cookware and the hugely successful “Germ-Proof Filter.” An ancestor of today’s water cooler, the filter provided sanitary drinking water in less-than-sanitary public places, such as offices and railway stations.

In the early 1900s, Fulper’s master potter, John Kunsman, began creating various solid-glaze vessels, such as jugs and vases, which were offered for sale outside the pottery. On a whim, William H. Fulper II (Abraham’s grandson, who’d become the company’s secretary/treasurer) took an assortment of these items for exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition—along with, of course, the Germ-Proof Filter. Kunsman’s artware took home an honorable mention.

Since Chinese art pottery was then attracting national attention, Fulper saw an opening to produce similarly styled modern ware. Dr. Cullen Parmelee, who headed up the ceramics department at Rutgers, was recruited to create a contemporary series of glazes patterned after those of ancient China. The Fulper Vasekraft line of art pottery incorporating these glazes made its debut in 1909. Unfortunately, Parmelee’s glazes did not lend themselves well to mass production; they did not result in reliable coloration. Even more to their detriment, they were expensive to produce.

In 1910, most of Parmelee’s glazes disappeared from the line. A new ceramic engineer, Martin Stangl, was given the assignment of revitalizing Vasekraft. His most notable innovation: steering designs and glazes away from reinterpretations of ornate Chinese classics and toward the simplicity of the burgeoning Arts & Crafts movement. Among his many Vasekraft successes: candleholders, bookends, perfume lamps, desk accessories, tobacco jars, and even Vasekraft lamps. Here, both the lamp base and shade were of pottery; stained glass inserts in the shades allowed light to shine through.

Always attuned to the mood of the times, William Fulper realized that by World War I the heavy Vasekraft stylings were fading in popularity. A new and lighter line of Fulper Pottery Artware, featuring Spanish Revival and English themes, was introduced. Among the most admired Fulper releases following the war were Fulper Porcelaines: dresser boxes, powder jars, ashtrays, lamps, and other accessories designed to complement the fashionable boudoir.

Fulper Fayence, the popular line of solid-color, open-stock dinnerware eventually known as Stangl Pottery, was introduced in the 1920s. In 1928, following William Fulper’s death, Martin Stangl was named company president. The artware that continued into the 1930s embraced Art Deco as well as Classical and Primitive stylistic themes. From 1935 onward, Stangl Pottery became the sole Fulper output. In 1978, the Stangl assets came under the ownership of Pfaltzgraff.

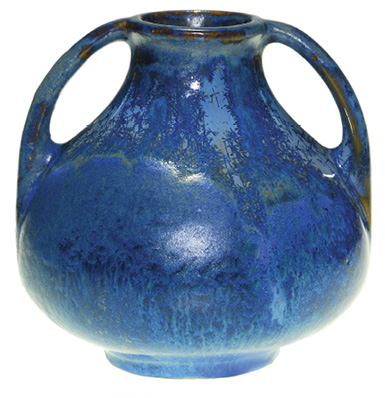

Unlike wheel-thrown pottery, Fulper was made in molds; the true artistry came in the use of exceptionally rich, color-blended glazes. Each Fulper piece is one-of-a-kind. Because of glaze divergence, two Fulper objects from the same mold can show a great variance. While once a drawback for retailers seeking consistency, that uniqueness is now a boon to collectors: each Fulper piece possesses its own singular visual appeal.

Rare VaseKraft lamp, Flemington Green flambé glaze, circa 1908, glazed ceramic, leaded glass, two sockets, base with rectangular ink stamp, patent pending, no. 22, shade numbered 22/33/28, 22" × 16" $13,750

Flower jug, Copperdust Crystalline glaze, 1916-1922, incised racetrack mark, 12" × 8" $1,500

Jar with pedestal, Cucumber Green crystalline glaze, 1916-1922, raised racetrack mark, 11 1⁄4" × 10 1⁄2" $4,063

Tall rare urn, blue and ivory flambé glaze, 1916-1922, raised racetrack mark, 14 1⁄2" × 9" $3,250

Jardiniere, Mirror Black glaze, 1910-1916, vertical black ink stamp, 8 1⁄4" × 10" $3,000

Art pottery candle sconce, 20th century, 10 3⁄4" high $395

Rare VaseKraft lamp, Cat’s Eye flambé glaze, circa 1908, glazed ceramic, leaded glass, two sockets, VaseKraft stamp, vertical rectangular ink stamp, patent pending, 17 1⁄2" × 14" $9,375

Two pairs of book blocks, Mission Bells and Chinese Gates, 1910-1916, Chinese Gates with vertical ink stamp, Mission Bells with paper label, 8" × 6 1⁄4", 7 1⁄4" × 5 1⁄2" $1,250

Handled vase with blue snowflake crystals over lilac gray, ink stamp racetrack mark, excellent original condition, 6" high $200

Pair of pillar candlestick vases, with glossy and mat glazes in several shades of green with touches of brown at rim, ink stamp racetrack logo, excellent original condition, 8 1⁄2" high $425

Urn, Green Crystalline glaze, 1910-1916, vertical rectangular ink stamp, 12" × 8 1⁄2" $1,000

Two seven-sided vases, shape 445, each covered with drip glazes; 8-3⁄4" version with green and black flambé glaze and marked with Fulper paper sticker; 8-7⁄8" version in brown and blue glazes dripped over yellow, marked with early rectangular ink stamp, excellent original condition. $550

4" cream pitcher and 4-5⁄8" lidded bowl, mat brown glaze, marked with early rectangular mark, mark on sugar cannot be read because glaze has covered it, each in excellent original condition. $140

“Bum” glazed ceramic doorstop, 1910s, unmarked, 8" × 9 1⁄2" × 6" $1,375

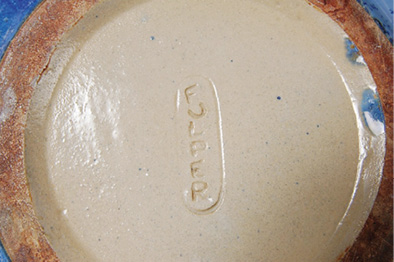

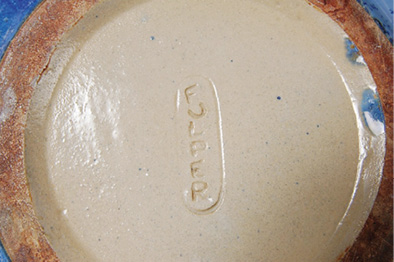

Vase with blue snowflake crystals, impressed oval Fulper logo, glazed over kiln kiss on fat part of vase, two uneven areas at rim, also glazed over, 9 1⁄2" high $190

“Bell pepper” vase in bluish-green mat glaze with yellow on top, incised racetrack mark, excellent condition, 4 1⁄4" high $350

Vase with cream flambé over Mirror Black glaze, raised vertical Fulper mark, several burst glaze bubbles and some tiny scratches, 16 1⁄2" high $850

Vaz bowl in Mirror Black over cream flambé, marked with vertical Fulper ink stamp logo and Panama-Pacific Expo paper label, also bears remnants of another Fulper paper label, excellent original condition with slight crazing in bowl, 6 3⁄8" high $180

Tall vase, Leopard Skin crystalline glaze, Flemington, N.J., 1910s, incised vertical racetrack mark, 12-1⁄2" × 7-1⁄2". $875

Handled vase in Mirror Black over butterscotch glaze, vertical racetrack ink stamp logo, small open glaze bubble on inside of rim, some kiln pulls on base, 11 3⁄4" high $425

Flambé Chinese sleeping cat doorstop in flambé Mirror Black with ivory glaze, rectangular Fulper stamp, stilt pull off bottom, excellent condition, 5 1⁄8" × 9 3⁄4" $1,200

Compote with blue crystalline glaze, marked with early rectangular ink stamp, small grinding nicks at base, 6" × 10-3⁄4". $140

Squatty gourd vase with green glaze over blue with small patches of cobalt, Prang mark on bottom, 3 3⁄4" high × 6 3⁄8" diameter $400

Tapered gourd vase in green mat glaze with tan at rim, incised racetrack mark, excellent condition, 5 5⁄8" high × 9" wide $275

Handled compote on raised base coated with mustard mat glaze, paler yellow interior encircled with streaks of brown-gray, center has splash of red-brown, unmarked, crazed interior, excellent original condition, 5" high × 12 1⁄2" wide $200

Vase with two squared handles, dark blue glaze dripped over Wisteria glaze, marked with larger rectangular ink mark, excellent original condition, 11" h. $250

Tall vase, Cucumber mat glaze, Flemington, N.J., 1910s, vertical racetrack stamp, 12-1⁄2" × 7-1⁄2". $1,250

Vase with Chinese Blue glaze over Wisteria, marked with vertical “racetrack” logo, some glaze pulls to bottom of vase, some small glaze bubbles, 8" h. $130

Vase, shape TP57 with three color glazes, beige, fawn and brown, marked with company’s earlier squatty ink logo, excellent condition, 7-3⁄4" h. $250

Vase with flambé glazes of green, brown and blue covering exterior of vessel and running into interior, rectangular “Prang” ink stamp, excellent original condition, 7-5⁄8" h. $325

Vase with four buttresses, shape 47, blue, gold and red high glaze, die-stamped with “incised” logo, excellent original condition, 8" h. $200

Two-handled vase, green glaze with large snowflake crystals, die-stamped with “incised” logo, excellent original condition, 8-3⁄4" h. $225

Six-sided vase covered with mahogany flambé glaze in yellow, blue and brown, impressed with “incised” mark, excellent original condition, 10-3⁄4" h. $250

Two vases with Wisteria glaze, 8-1⁄8" vase with green applied at rim, 7-3⁄4" vase impressed with pottery logo, other has oval inkstamp, some roughness at rim of smaller vase, both in original condition. $150

Leopard Skin three-handled vase with black and white crystals, marked with vertical ink stamp logo, 6-3⁄8" h. $1,600

Large early vase, 1909-1916 era, green dripped over Wisteria glazes, marked with rectangular Fulper ink stamp, excellent factory condition, 10-3⁄8" h. $200

Early corseted vase, gray and mahogany glazes, marked with rectangular ink stamp, excellent original condition, 7-1⁄8". $325

Large vase with Ivory over Mahogany to Mirrored Black glazes with some blue accents, impressed with Fulper “incised” mark, excellent original condition with some grinding nicks at base, 12-1⁄4" h. $450

Vase, shape 523, mat maroon glaze over blue, marked with vertical ink stamp logo, excellent original condition, 10" h. $300

Bud vase with stovetop neck, variegated blue mat glaze, large rectangular ink mark dating vase to 1909-1916 era, excellent original condition, 5-1⁄2" h. $80

Vase, shape 581, Cucumber Crystalline glaze or variant, snowflake crystals, vertical ink stamp symbol and incised D 581, excellent original condition with flat chip or pull to interior edge of foot ring, 9-1⁄2" h. $200

Vase, shape 567, blue, green and purple glazes in both mat and glossy, raised Fulper logo, excellent original condition with some minor glaze bubbles, 6-5⁄8" h. $375

Vase, shape 537, blue, green and tan crystalline glaze, die-stamped “incised” logo, excellent original condition, 7-1⁄2" h. $200

Vase, shape 17, textured brown glaze over blue high glaze, marked with Fulper rectangular ink stamp, small chip at base, 3-5⁄8". $110

Large urn-shape vase with two handles, blue green glaze with blue crystals, marked with large rectangular ink mark, professional restoration at base, 12" h. $200

Vase, shape 537, black and yellow flambé glaze with blue highlights, marked with die-stamped “incised” logo, excellent original condition, 7-3⁄8". $120

Vase with spouted rim and gloss green glaze, marked with early Fulper rectangular logo, few minor glaze bubbles, excellent condition, 7-1⁄4" h. $100

Cylinder vase, shape 57, dark blue glaze applied over Famille Rose, marked with “h,” trial mark, and Fulper’s earliest mark, excellent original condition, 8" h. $180

Three-handled “Bullet” vase with glossy green glazes applied over Wisteria mat glaze, vertical “racetrack” ink stamp, excellent factory condition, 6-1⁄4" h. $250

Necked vase with mat Aqua Green Crystalline glaze, racetrack logo, excellent condition, 7 3⁄4" high $150

Baluster vase, Chinese Blue flambé glaze, 1916-1922, vertical incised racetrack mark, 11 1⁄2" × 8 1⁄2" $1,750

Vase with oatmeal glaze over Mirrored Black, impressed with die-stamped “incised” mark, shape 536, small grinding chips at base, 13-1⁄2" h. $700

Vase, 1916-1922 era, textured mat green glaze, die-stamped “incised” mark, excellent original condition, 7" h. $250

Lamp vase in Mirrored Black glaze over Copper Dust glaze, vase has 14 ribs, Mirrored Black has many small silver crystals, Copper Dust is totally crystallized; marked with vertical ink stamp logo offset to accommodate cast wiring hole, excellent original condition, 13" h. $600

Handled pitcher, Oriental form hybridized with addition of handle, 1916-1922, Copper Dust crystalline glaze, marked with die-stamped “incised” mark, three flat chips to foot ring, 11-3⁄8" h. $1,800