GOUDA IS ONE of the decorative art world’s strong and silent types, not withstanding its beautifully bright colors and rich floral and abstract designs – considered by many to be its calling card. While its place in today’s market is less robust than some of its contemporaries, such as Weller and Rookwood, its pairing of subtle strength of identity and eye-catching design is what attracts people to it and makes it a collecting category to watch.

One of the indicators that Dutch pottery shouldn’t be counted out is that higher-end pieces continue to attract attention, not unlike many other categories of antiques today.

“There appears to be a line in the sand with Gouda right now,” said Stuart Slavid, vice president and director of Fine Ceramics, Fine Silver, European Furniture & Decorative Arts at Skinner, Inc. “Spectacular pieces are still doing very well, but there is very little or no movement at all for lower-end pieces.”

The reasons for that vary, but some contributing factors appear to be advanced collectors looking for advanced pieces rather than more basic items; and the way in which people collect overall has changed some, Slavid explained.

“It used to be more people would start with good pieces, move to better pieces and then to great. Now more people with available discretionary income are starting with the very best pieces,” he said.

Riley Humler, auction director and art pottery expert at Humler & Nolan, echoed Slavid’s sentiments, adding that high-end pieces in every collecting arena are doing far better than the rest.

“I think the reason is serious collectors are looking for better pieces and avoiding lesser items,” Humler said. “Quality has finally taken over for quantity. Part of that may be that serious collectors are generally older and have money. There are not enough young collectors to buy the more reasonable pieces, so one end of the market is doing fairly well and the other, not so well.”

High glaze vase, Rozenburg den Haag, coiling design of butterflies and sunflowers, factory mark with data code and incised V.W 189, early 20th century, 19 1⁄2" h. $4,444

Two high glaze Zuid-Holland Gouda vases, tallest measuring 12" h., painted with florals, Netherlands, circa 1905. $3,375

As with many situations, there are exceptions to the status quo, and that’s also true in today’s Gouda pottery market. While the most common Gouda pieces are seen in matte finishes, which are more modern and also more plentiful, early pieces, especially those with birds or butterflies under their gloss finishes, may be somewhat hard to find and tend to be more interesting, according to Humler.

Another example of an exception to the overall slowdown of interest in Gouda is white ground ware, which remains popular, according to experts at Rago Arts. At an unreserved auction on Jan. 12-13, 2013, at Rago Arts, the highlight of the 33 available lots of Gouda pottery was a pair of high-glaze white Zuid-Holland vases, circa 1905, featuring a floral motif, which sold for $3,375 – more than three times the lot’s high estimate. Of the Gouda pieces featured at this sale, 22 commanded more than their low estimate, and of those 22 lots, eight fetched more than their high estimate.

Looking at the history of Gouda pottery, it’s possible the founders of the earliest factories would be surprised to see what has become of their pottery — especially since many of the first companies to produce Gouda pottery did so to diversify their primary operation of clay pipe production. With an abundance of clay in the Gouda region of the Netherlands, it made good sense for the companies to expand into pottery; and the public demand confirmed it, according to information on the Museum Gouda website, www.museumgouda.nl.

It was 1898 when Plateelbakkerij Zuid-Holland, often referred to as PZH or Zuid-Holland, produced their first piece of Gouda pottery. Named for the region in the Netherlands, Gouda encompasses the pottery produced by several factories located there. While the earliest examples of Gouda were not the same as the brightly colored, matte glaze pieces collected today, they were often sought after for the same reason as today: décor for the home.

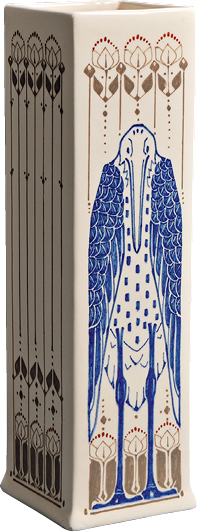

High-glazed rectangular form vase, circa 1930, elongated stork designed in blue with Art Deco-influenced geometric floral accents, cream ground, marked 217, 12" h., hairline crack near base. $338

However, like many types of pottery, it didn’t necessarily start out that way, said Joe Altare, founder of the Regina Pottery Collectors site (www.reginapottery.com). “One of the key points to remember about these wares is that some were designed as giftware and others for day-to-day use,” Altare said. “Both were marketed to the middle class, who finally had discretionary income to purchase decorative, rather than utilitarian wares.”

People, then and now, are drawn in by the remarkable colors and designs.

“I stumbled across my first piece, a Regina compote, on eBay about 10 years ago. I knew nothing about Gouda pottery or the Regina factory, but the design captivated me and I had to have it,” said Altare. “The design, variety and quality of execution captured my attention, and the many untold secrets of the [Regina] factory have fueled my passion these many years.”

Although many of the companies that produced Gouda pottery remained in operation through the mid-1960s and 1970s, many consider the heyday of Gouda to have lasted through the first three decades of the 20th century. In fact, in the 1920s, a quarter of the workforce in the Gouda region was employed in the pottery industry, according to Museum Gouda.

While Gouda pieces may not be setting high-profile auction records today, it remains a strong and serious representative of the ingenuity of decorative pottery. Plus, as more people are shopping at places like IKEA and Crate & Barrel for modern décor and furnishings, decorative pottery like Gouda lends itself nicely to that scene.

“I think Gouda fits very well in that space. It just hasn’t caught on yet,” said Slavid.

In addition to fitting into society’s modern décor and design interests, another advantage for Gouda is that it is more affordable, according to Humler. “Even the best pieces are in most people’s price range,” he said.

With a history steeped in innovation primed by practicality and fans across the globe, a renewal and widespread rediscovery of Gouda pottery isn’t out of the question.

— Antoinette Rahn

Experimental floor vase, Zuid-Holland Gouda pottery, 20th century, matte glaze, baluster-form with spreading foot and intricate decoration of three owls interspersed with Rorschachesque designs, cream-colored ground, painted Gouda Zuid Holland and incised 226 A, 25 3⁄4" h., short hairline crack on lip of rim. $4,444

Four pieces: Arnhem Gouda, Purdah bowl, lidded box, Olivia tray, Creta bowl, Netherlands. $406

Four pieces: Zuid-Holland Gouda, 20th century Goes tray, Goedewaagen Orchidee charger, Sabany, lidded dresser boxes, Netherlands, all marked. $344

Nine pieces: two Unique Metalique vases, Muvlee bowl and pitcher, Deco bulbous vase, Unicum vase, pitcher in raspberry glaze, and two plates by Leendert Muller, all marked, 1930-1950s, Netherlands. $313

Three-piece clock garniture, Zuid-Holland Gouda pottery, Netherlands, circa 1910, clock 20 1⁄2" $1,750

Four pieces: jug, pair of mini vases and chamberstick, Netherlands, circa 1910. $125

Five piece grouping: Zenith Clematis jardinière (center back and measuring 10" × 15 1⁄2" × 13" dia.) and fire bottle (far right), three Ed Antheunis vases (starting at far left): Rola, Bagdhad and Rolf, all pieces circa 1920. $219

Eight-piece grouping of marked pottery from Gouda and Arnhem, Netherlands, early 20th century, Francis and Feo tazzas (far left and far right front), footed Yannis bowl, 1926 (second from left front), Abo flaring low bowl, 1931 (front center), a tray and three vases (back row, left to right). $500

Five pieces of Gouda pottery, early 20th century, Netherlands, all marked, Violette jug with stopper (far left and tallest at 9 1⁄4"), Maas creamer (front left), double-handled bud vase (center), Rozenburg gourd-shape vase (back right), and bowl (far right). $438

Six pieces, early 20th century, Netherlands, all marked, Ponseav bud vase (back left), squat bowl (middle back), bottle-shaped vase with portrait (right middle and tallest piece measuring 11"), cup with tulips (back far right), double-handled bowl with irises (front left), bowl with tulips (front right). $563

Mat jug and vase painted with florals and birds, Netherlands, circa 1910. $563

Pairing, early 20th century PZH modern Gouda vase with Rembrandt inkwell. $219

Numbered Zuid-Holland Gouda matte glaze charger, circa 1925, Rosalie pattern, bird on branch centering blossoming branches, PZH factory mark, 14 1⁄4" dia. $830

Rozenburg den Haag Gouda high glaze charger from the Netherlands, early 20th century, decorated with a bouquet of flowers on pale yellow, deep green, and deep blue ground, painted factory mark, 17 1⁄2" dia. $1,007

Seven pieces: 20th century Zuid-Holland Gouda vases, bowl, gourd-form vase, framed watercolor. $438

Seven pieces, 20th century Zuid-Holland Gouda: charger, footed bowl, bottle-shaped vase, Iantem, Crocus chambersticks, Blaren bowl. $563

Nine pieces: 20th century Goedewaagen/Distel bowl, Ivora plaque, Schoonhoven lidded Isis box, PZH Helene bud vase, salt and four pieces featuring windmill and sailboat paintings. $156

Fourteen pieces: Chambersticks, candlesticks, basket, inkwell, vases, tray, bowl, lidded jar, all from the 1920s, Netherlands. $813

16-piece Ispahan tea set: teapot, creamer, sugar, tall pitcher, and set of six cups and saucers, Netherlands. $88

Four pieces: footed Gouda bowl and jug in Clareth pattern, Clara vase and Barbara low bowl, all signed with pattern name. $344