Eagle shape white ironstone gravy boat, Davenport, circa 1859s. $110

DURABILITY: WHEN INTRODUCED in the early 1800s, that was ironstone china’s major selling point. Durability also accounts for the still-ready availability of vintage ironstone china, literally centuries after it first captivated consumers. Unlike its fragile porcelain contemporaries, this utilitarian earthenware was intended to withstand the ravages of time—and it did.

Ironstone owes its innate sturdiness to a formula incorporating iron slag with the clay. Cobalt, added to the mix, eliminated the yellowish tinge that plagued earlier attempts at white china. The earliest form of this opaque dinnerware made its debut in 1800 England, patented by potters William and John Turner. However, by 1806 the Turner firm was bankrupt. Ironstone achieved its first real popularity in 1813, when Charles Mason first offered for sale his “Patent Ironstone China.” Mason’s white ironstone was an immediate hit, offering vessels for a wide variety of household uses, from teapots and tureens to washbowls and pitchers.

Although the inexpensive simplicity of white ironstone proved popular with frugal householders, by the 1830s in-mold and transfer patterns were providing a dose of visual variety. Among the decorative favorites: Oriental motifs and homey images such as grains, fruits, and flowers.

Mason’s patented formula for white ironstone lasted for 14 years. Upon its expiration, numerous other potteries jumped into the fray. By the 1840s, white ironstone found its way across the ocean, enjoying the same success in the United States and Canada as it had in England. By the 1880s, however, the appeal of white ware began to fade. Its successor, soon overtaking the original, was ironstone’s most enduring incarnation, Tea Leaf.

First marketed as Lustre Band and Sprig, the Tea Leaf Lustreware motif is attributed to Anthony Shaw of Burslem; his ironstone pieces of the 1880s featured hand-painted copper lustre bands and leaves. Tea Leaf was, however, a decorative style rather than a specific product line. Since the design was not patented, potteries throughout England and the United States soon introduced their own versions. Design modifications were minor; today, collectors can assemble entire sets of ironstone in the Tea Leaf pattern from the output of different manufacturers. Although independently produced, the pieces easily complement each other.

Eagle shape white ironstone gravy boat, Davenport, circa 1859s. $110

Rare Ceres shape ironstone eggcup, Elsmore & Forster, all white. $225

Figural hen-on-nest covered dish, all white. $225

During the late 1800s, ironstone tea sets were so ubiquitous that ornamenting them with a tea leaf was a logical choice. Buyers were intrigued with this simple, nature-themed visual on a field of white. Their interest quickly translated into a bumper crop of tea leaf-themed ironstone pieces. Soon, the tea leaf adorned objects with absolutely no relation whatsoever to tea. Among them: gravy boats, salt and peppers shakers, ladles, and even toothbrush holders and soap dishes.

There were, of course, more romantic rationales given for the introduction of the tea leaf motif. One holds that this decoration was the modern manifestation of an ancient legend. Finding an open tea leaf at the bottom of a teacup would bring good luck to the fortunate tea drinker. In this scenario, the tea leaf motif becomes a harbinger of happy times ahead, whether emblazoned on a cake plate, a candlestick, or a chamber pot.

For makers of Tea Leaf, the good fortune continued into the early 1900s. Eventually, however, Tea Leaf pieces became so prevalent that the novelty wore off. By mid-century, the pattern had drifted into obscurity; its appeal was briefly resuscitated with lesser-quality reproductions, in vogue from 1950 to 1980. Marked “Red Cliff” (the name of the Chicago-based distributor), these reproductions generally used blanks supplied by Hall China.

For today’s collectors, the most desirable Tea Leaf pieces are those created during the pattern’s late-Victorian heyday. Like ironstone itself, the Tea Leaf pattern remains remarkably durable.

New York shape teapot, luster band trim, Clementson. $60

Ceres shape dinner plate, dessert plate and handle less cup and saucer, green and copper luster trim. $30-$50 set

Corn & Oats shape white ironstone mug, Davenport. $90-$110

Alternate Panels ironstone compote, all white. $225

Pond Lily Pad shape white ironstone relish dish, James Edwards. $115-$130

Chinese shape white ironstone mug, Anthony Shaw, circa 1858. $90

Classic Gothic Octagon shape white ironstone soup tureen, cover, undertray and ladle, Samuel Alcock & Co., circa 1847. $1,200 set

Berlin Swirl shape white ironstone covered vegetable tureen, T.J. & J. Mayer. $190

Olympic shape white ironstone sugar bowl, covered, Elsmore & Forster, 1864. $90

Inverted Diamond shape white ironstone teapot, covered, T.J. & J. Mayer, England, circa 1840s. $250-300

Classic Gothic Octagon shape master waste jar, all white, Jacob Jurnival. $950-$1,050

Scalloped Decagon/Cambridge shape white ironstone sugar bowl, Wedgwood & Co. $100

Sydenham shape white ironstone teapot, covered, copy of Victorian ironstone original design produced by Hall China for Red Cliff, circa 1960s. $95

Alternate Panels shape white ironstone teapot, unknown pottery, England, mid-19th century. $125-$150

Divided Gothic shape white ironstone washbowl and pitcher set, John Alcock, circa 1848. $400-$450 set

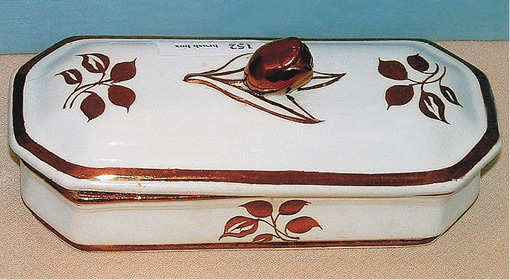

Tobacco Leaf pattern, Fanfare shape covered toothbrush box, Elsmore & Forster, rare. $675

Dolphin-handled shape white ironstone wine pitcher, unmarked, circa 1850s. $110-$130

Ginger Jar shape Tea Leaf ironstone master waste jar, covered, Elsmore & Forster, rare. $1,300

Grape Octagon shape washbowl and pitcher set, luster band trim, unmarked. $225

Imari-style soup bowls, English, 19th century, unmarked, 10 in. dia. $150

Empress shape Tea Leaf ironstone two-handled cream soup bowl, Micratex by Adams, circa 1960s. $35

Lily of the Valley shape Tea Leaf ironstone chamber pot, Anthony Shaw. $175

Rare Paneled Grape shape jam server, covered, by J.F. $110-$140

Cable shape Tea Leaf ironstone butter dish, cover and insert, Anthony Shaw. $60

Favorite shape Tea Leaf ironstone coffeepot, covered, Grindley. $170

Tulip shape white ironstone teapot, covered, trimmed in blue, Elsmore & Forster, England, circa 1855 . $290-$320