KNOWN FOR ITS finely detailed figurines and exceptional tableware, Meissen is recognized as the first European maker of fine porcelain.

The company owes its beginnings to Johann Friedrich Bottger’s 1708 discovery of the process necessary for the manufacture of porcelain. “Rediscovery” might be a better term, since the secret of producing hard paste porcelain had been known to the Chinese for centuries. However, Bottger, a goldsmith and alchemist, was the first to successfully replicate the formula in Europe. Soon after, The Royal Saxon Porcelain Works set up shop in Dresden. Because Bottger’s formula was highly sought after by would-be competitors, in 1710 the firm moved its base of operations to Albrechtburg Castle in Meissen, Saxony. There, in fortress-like surroundings, prying eyes could be successfully deflected. And, because of that move, the company name eventually became one with its locale: Meissen.

The earliest Meissen pieces were red stoneware, reminiscent of Chinese work, and incised with Chinese characters. Porcelain became the Meissen focus in 1713; early releases included figurines and teasets, the decorations reminiscent of baroque metal. In 1719, after Bottger’s death, artist J.J. Horoldt took over the firm’s direction. His Chinese-influenced designs, which employed a lavish use of color and decoration, are categorized as chinoiserie.

By the 1730s, Meissen employed nearly 100 workers, among them renowned modelers J.G. Kirchner and J.J. Kandler. The firm became known for its porcelain sculptures; subjects included birds, animals, and familiar figures from commedia dell’arte. Meissen dinnerware also won acclaim; in earlier attempts, the company’s white porcelain had only managed to achieve off-white. Now, at last, there were dazzling white porcelain surfaces that proved ideal for the exquisite, richly colored decoration that became a Meissen trademark.

Pair of fox head stirrup cups, 19th century, 3 1⁄4" high $1,778

Following Horoldt’s retirement in the mid-1700s, Victor Acier became Meissen’s master modeler. Under Acier, the design focus relied heavily on mythological themes. By the early 1800s, however, Meissen’s popularity began to wane. With production costs mounting and quality inconsistent, changes were instituted, especially technical improvements in production that allowed Meissen to operate more efficiently and profitably. More importantly, the Meissen designs, which had remained relatively stagnant for nearly a century, were refurbished. The goal: to connect with current popular culture. Meissen’s artists (and its porcelain) proved perfectly capable of adapting to the prevailing tastes of the times. The range was wide: the ornate fussiness of the Rococo period; the more subdued Neoclassicism of the late 1700s; the nature-tinged voluptuousness of early 20th century Art Nouveau; and today’s Meissen, which reinterprets, and builds on, all of these design eras.

Figure group depicting elegant woman in 18th century dress standing over cherub reading book, surrounded below by ladies-in-waiting and two girls, ovoid naturalistic base, late 19th/early 20th century, 12" high $6,463

Despite diligent efforts, Meissen eventually found its work widely copied. A crossed-swords trademark, applied to Meissen pieces from 1731 onward, is a good indicator of authenticity. However, even the markings had their imitators. Because Meissen originals, particularly those from the 18th and 19th centuries, are both rare and costly, the most reliable guarantee that a piece is authentic is to purchase from a reputable source.

Meissen porcelain is an acquired taste. Its gilded glory, lavish use of color, and almost overwhelmingly intricate detailing require just the right setting for effective display. Meissen is not background décor. These are three-dimensional artworks that demand full attention. Meissen pieces also often tell a story (although the plots may be long forgotten): a cherub and a woman in 18th century dress read a book, surrounded by a bevy of shepherdesses; the goddess Diana perches on a clock above a winged head of Father Time; the painted inset on a cobalt teacup depicts an ancient Dresden cathedral approached by devout churchgoers. Unforgettable images all, and all part of the miracle that is Meissen.

Clock, figural, Rococo taste, tall case molded as cartouche applied with flowering garlands enclosing clock with white porcelain dial with Roman numerals, held by figure of seated goddess Diana, raised on tall waisted rocaille pedestal molded with winged head of Father Time above small putto petting Diana’s dog, center hand painted with color vignette of couple in wooded landscape, scrolled feet, sides and back trimmed with gilt flowers, retailed by Tiffany & Co., New York City, mid-to-late 19th century, 15 1⁄2" high $6,573

Porcelain figurine titled “Duck Sale,” marked on underside with gray M and impressed numbers 720 62, very good to excellent condition, 6 1⁄2" high × 6" wide. $830

Four items, late 19th century, each polychrome enameled and gilded, including pair of figures of man and woman, each supporting floral garland, 6 1⁄4" high, 6 1⁄2" high; pair of covered urns with foliate festoons above figural landscape scenes, 5" high; crossed swords marks $1,722

Set of eight bird plates, 19th century, 8 1⁄2" diameter, together with two floral plates, 9 1⁄2" diameter $652

Reticulated floral bowl, 6" high, 10" diameter $59

Pair of porcelain vases, late 19th/early 20th century, scrolled snake handles, gilding to rim, handle terminals, lower body, and socle, crossed swords marks, 15 3⁄8" high $984

Four porcelain busts, circa 1900, each with blue crossed swords mark, comprising three allegorical of the seasons, one with single cancellation mark, incised model numbers and bust of Renaissance maiden, incised L17, 8 1⁄4" to 11" high $2,750

Three vases, circa 1900, each with underglaze blue crossed swords mark, flanked by serpent handles centered by floral sprays or bunches of fruit, largest with double cancellation and impressed A148/67, pair impressed or incised E153, tallest 19" high $1,250

Pair of porcelain flower sellers, late 19th century, gilded and polychrome enamel decorated figures, man holding hat full of flowers, woman a basketful, each with underglaze blue crossed swords marks, 6 1⁄4", 6 5⁄8" high $1,320

Pair of porcelain figures with garlands, late 19th century, each gilded and polychrome enamel decorated, man supporting garland atop his shoulders, woman holding garland across her chest, underglaze blue crossed swords marks, 6 3⁄8", 6 1⁄2" high $960

Porcelain figural group, late 19th century, polychrome enamel decorated and gilded with figures of two boys supporting girl on stilts, all by sculpture of classical maiden, crossed swords mark, heavy losses to leaves and branches, restored to small scattered chips, basket on backside missing handle, 10 3⁄8" high $1,920

Porcelain swan group, 19th century, gilded and polychrome enamel decorated, modeled as mother swan with two of her young, crossed swords mark, 4 5⁄8" high $450

Porcelain allegorical figural group, 19th century, gilded and polychrome enamel decorated, modeled as seated Cupid dressed in long coat and wearing hat and surrounded by three maidens, blue crossed swords mark, first quality mark, restorations to kneeling maiden’s neck and arms, seated maiden’s back of seat, cupid’s legs, 7 1⁄4" high $2,091

Five porcelain figures, 19th century, each gilded and polychrome enamel decorated, including youth playing shuttlecock, 5 7⁄8" high; youth playing flute, 5 3⁄4" high; young girl feeding chickens, 4 5⁄8" high; young boy with barrel of grapes, 3 5⁄8" high; and maiden riding back of steer, 3 3⁄8" high; crossed swords marks $1,968

Group of Meissen porcelain tablewares, German, in Blue Onion pattern, three reticulated luncheon plates, six reticulated dessert plates, five reticulated bread plates, cup and saucer, and shaped rectangular platter with gilded rim, all with underglaze blue double crossed sword mark, except one bread plate marked MEISSEN within a circle, plus three Continental reticulated dessert plates, marked KS within a circle, platter has losses to gilding, platter 13-1⁄2" l. $330

Porcelain courting group, late 19th century, gilded trim with polychrome enameling to man and woman seated beneath tree, rabbit by their feet, underglaze crossed swords mark, first quality mark, loss and old repairs to numerous leaves, rabbit missing half of rear leg, restored to end of sword, 9 3⁄4" high $1,320

Hunter on horseback with dogs, German, late 19th century, marks: crossed swords, T 102, good condition with restoration to tail of one dog, 15-1⁄4" h. $18,125

Group of seven tablewares, German, in Blue Onion pattern, coffee pot, two lidded milk pots, two lidded jars, one with silver top, vinegar bottle and two-handled covered bowl with putto finial, all with blue underglaze crossed swords mark, except for coffee pot, which is marked MEISSEN under a cross, lidded bowl missing ladle with small chip to finial, repair to base of milk pot, tallest 7-1⁄2". $480

Pair of porcelain cobalt blue ground vases and covers, late 19th century, each with gilded scrolled foliage surrounding shaped cartouches, polychrome enamel decorated with courting figures on one side, floral bouquets on reverse, underglaze crossed swords marks, finial restored to one cover, 9 3⁄8" high $1,230

Five porcelain figures, 19th century, each gilded and polychrome enamel decorated, including male youth, 7 1⁄4" high; woman with bird in apron, 7 1⁄8" high; posing dandy, 6 3⁄4"; man hiking, 7"; and harlequin and maiden dancing, 7"; crossed swords marks $3,900

Figural perforated vase with lid, 19th century, some damage, 12-1⁄2" h. $950

Porcelain group of Abduction of Prosperpine, circa 1900, underglaze blue crossed swords mark with double cancellation, incised 1787, impressed 125 and black painted 57, 8" high $750

Porcelain figural group, late 18th/early 19th century, gilded and polychrome enamel decorated, modeled as farmer with cow and milkmaid, underglaze blue crossed swords mark, 7 3⁄8" high $1,140

Porcelain lover’s group, late 19th century, polychrome enameled and gilded model depicting man and woman in amorous pose, lamb by their side, crossed swords mark, first quality mark, restoration to woman’s hand by lamb and to ribbons of man’s hat, scattered chips to flowers and leaves, 7 1⁄2" high. $1,440

Tureen and platter, German, in Blue Onion pattern, lidded tureen and shaped oval platter with handles, both with underglaze blue crossed swords mark, tureen missing ladle, small chip to handle of platter, platter 20 ” l. $510

Porcelain group of Venus and attendants, centered by Venus seated in shell chariot riding a wave, surrounded by attendants in form of putti, dolphins, and mermaids, underglaze blue crossed swords with single cancellation, late 19th century, incised D81, impressed 68 and red painted 41, 8 1⁄2" high $2,057

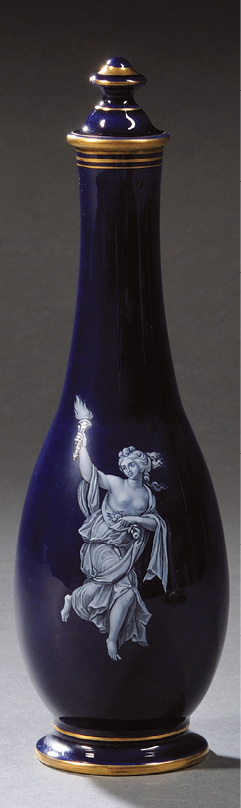

Porcelain blue ground vase and cover, 19th century, bottle shape with gilded trim lines and decorated in white and black enamel with classical maiden on either side, underglaze blue crossed swords mark, 8 5⁄8" high $1,968

Malabar Lady and Malabar Man, late 19th century, marks to female: crossed swords, 1519, 12-1⁄2" h. $3,750

Group of 10 Meissen Blue Onion porcelain salts, German, two master salts surmounted by seated putti, two salts with shell-shaped bowls on scrolling feet, and six square salts, all with underglaze blue crossed swords mark, master salts incised with M129 style mark, largest 6" h. $570

Porcelain figural courting group, late 19th century, polychrome enameled and gilded depiction of maiden centering male suitor, another kneeling by column with lovebirds in his hat, crossed swords mark, first quality mark, restoration to standing suitor’s back hand, 12" high $2,583

Figural grouping, German, late 18th/early 19th century, 15" h. × 8-1⁄2" w. $500

Leda and the Swan, German, late 19th century, marks: crossed swords, 433, some losses to top of toe on extended foot, floral garland, and tree leaves, 6-3⁄4" h. $1,250

Porcelain figural courting group, late 19th century, polychrome enameled and gilded model with three figures, maiden with suitor, another maiden grieving by her side, crossed swords mark, first quality mark, restoration to bow in maiden’s hat, maiden’s arm resting on shoulder of other maiden, basket of flowers, fingers of hand at basket, 12 1⁄4" high $2,400

Nine items with gilt and floral decoration, 19th/20th century: six round bowls, two-handled rectangular bowl and square serving tray, all marked, tray 16" sq. $2,625

Porcelain blue onion three-tier cake plate with figural woman with flowers finial, bottom with blue crossed swords mark with number 2, circa 1860-1880, 21 1⁄2" high $1,936

Cup and saucer, cup 2" h. × 3" dia., saucer 5" dia. $50

Porcelain figural footed compote with applied floral decoration, 19th/20th century, crossed swords mark, 19" × 14" × 11-1⁄2". $2,375

Hand-painted porcelain urn covered with applied putti and large floral finial, 19th century, crossed swords mark, 24" × 12" × 9-1⁄2". $4,063

Porcelain yellow ground vase and cover, early 20th century, gilded griffin head handles, polychrome enamel decorated oval cartouches with nude nymph to either side, underglaze crossed swords mark, slight hairline through figure on one side, 15 5⁄8" high $923

Gardener figure, German, 19th century, woman in 18th-century attire with basket of flowers, holding tool, standing beside rose-filled planter on circular base, marked with underglaze blue crossed swords, incised 122 on bottom, chip to rim of bonnet, minor losses to lace and flowers, missing blade of sickle, 8-1⁄2" h. $900

Pair of porcelain cobalt ground plates, 19th century, each with pierced floret and ringlet border and polychrome enamel decorated cartouches, one depicting Triumph of Bacchus, the other Renaud and Armide, titled in French, crossed swords marks, 9 1⁄8" diameter $3,321

Two porcelain figures from “The Senses” series, German, late 19th century, representing taste and smell, both with woman in 18th-century attire, seated at a table, one smelling a rose and the other enjoying a pastry, each marked with underglaze blue crossed swords, “taste” incised 127 on bottom, “smell” incised 42 on bottom, both groups with minor losses, tallest 5-1⁄2" h $1,920