First and foremost, this book is a celebration of a British icon who also happened to be my dad!

I joined the Morecambe & Wise bandwagon in April 1956, but was not conscious of it until after my fifth birthday when I saw my father on TV for the first time, which is when he and Ernie started broadcasting their half-hour Morecambe & Wise shows for ATV. This coincided with my arrival at primary school, and, at this first rung on the educational ladder, I came into regular contact with the earliest TV critics – none of them older than eight! What they gave me was an understanding of how Morecambe & Wise were perceived outside the four walls of our house. It is not surprising therefore that this was the moment I chose to put my father on a pedestal.

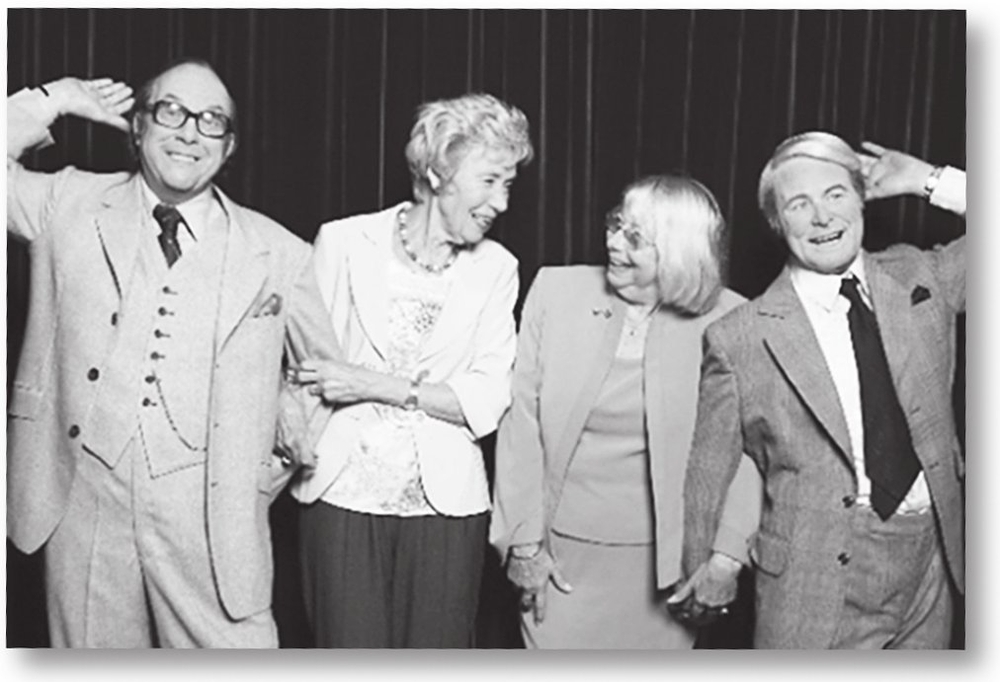

The author with his dad! A publicity shot we had taken in 1982, prior to a joint appearance on Russell Harty’s chat show. – GM

Just because he was on a pedestal, and has remained there for me even now as I write these words at the tender age of fifty-six, doesn’t mean every day is a rose-tinted memory. As a father and son, we could argue quite easily – but Dad and comedian Eric Morecambe were two different things to me, and they were to him, too, as he mostly referred to their double act in the third person.

I suppose that, until I was a teenager, squabbling or doing anything that was considered unbecoming was completely off the agenda. But what a ten-year-old might go along with, a seventeen-year-old does not.

It’s strange to recall that even my teenage angst (what little there was of it) was diffused by his humour. It’s really difficult to be the defiant child when the parent doesn’t outwardly disagree with any opinions you have, but with comedic precision exposes the limitations of your thought processes. And it was so difficult to outrage a man who never understood the meaning of embarrassment.

The only way to upset my father was to mention Ernie Wise in a negative way. He could say what he wanted at any given moment about his partner, but that wasn’t a licence for you to join in. It’s something I’ve given much thought to in recent times, and my conclusion would be that each was very protective of the other – they’d been together since the age of twelve or thirteen. ‘Closer than brothers’, their scriptwriter Eddie Braben has described them. I wouldn’t argue with that. I know, for instance, that they would finish each other’s sentences in a manner suggestive of a childhood spent together.

I wrote in an earlier book about my father that it would certainly be my last written work about Eric Morecambe. And so it would have been had not circumstances contrived to occasion what you are now reading.

It began on a visit to my mother’s house at the beginning of 2011. On arriving at the old family home, filled with childhood memories coloured by my father’s massive personality, I found her in the kitchen waving a copy of The Times newspaper in her hand. She showed me a photo of my father taken at a Luton Town FC event. It was a photo neither of us had set eyes upon. ‘Imagine how many photos of Dad must be out there that we haven’t seen,’ she remarked, unaware what impact those words were to have on me.

‘Yes,’ I nodded. ‘Wouldn’t it be great to collect some of them and put them into a book so we have a permanent record?’

It was just a throwaway comment, but one that would lead to precisely that end. At that particular time though, the thought of trawling through my own and others’ personal photographic collections, as well as those of the media, to collate photos of my father was not a realistic one. I was busy with other things, particularly directing a run of short films for transmission on selected satellite TV channels, and my intention never to do any more Morecambe & Wise-related books had not been formed lightly. I’d been writing books related to my father on and off for some thirty years – surely that was enough!

A friend and erstwhile colleague Paul Burton was directing another short film I was producing at Elstree Studios. In a coffee break, I mentioned the photo my mother had seen. ‘It would make a great book,’ he said, and immediately offered his services for research purposes, it being one of his main lines of employment and one area that had been dulling my enthusiasm. Another step towards taking an idle thought and turning it into a reality was unexpectedly made.

Two more made it impossible for me to turn down the opportunity of making the book a reality. While discussing the idea with Paul Burton, I mentioned the vague notion of making the book to my longtime publishing friend of some thirty or more years, Jeremy Robson. Jeremy had published several of my previous titles, including Behind the Sunshine: The Morecambe & Wise Story, and Cary Grant: In Name Only, both of which I co-wrote with the author, playwright and Coronation Street script-writer Martin Sterling. Jeremy said it was a wonderful idea and just the sort of title to which they could do justice.

Finally, I mentioned the idea to my newest friend and Morecambe & Wise fan, comedienne Miranda Hart, taking the liberty of asking her if, should this book happen, she would be willing to write a foreword. ‘Willing!’ she told me. ‘It would be an honour.’

And so the process of creating a book of rare photographs – certainly the vast majority of which I had never seen before – began and into the mix came some curious memorabilia from my father’s former study, and memories of those who, however briefly, came into contact with him.

Rummaging through my father’s mine of papers and photographs always quickly puts me in mind of Morecambe & Wise. The TV shows come flooding back, the classic lines so easily remembered. ‘Have you got the scrolls? No. I always walk like this!’ ‘I’m playing all the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order!’ ‘He’s not going to sell much ice cream going at that speed!’ ‘What do you think of it so far? Rubbish!’ And so on. You would think I would be bored of it all by now, but, if boredom for the subject hasn’t struck me in my mid-fifties, then it is unlikely it ever will.

The nation’s enduring love for the duo never fails both to amaze and inspire me. Last Christmas, they were on TV in a documentary, a Parkinson interview, TV specials and a film (spanning three different channels) eight times! The previous festive season gave us Victoria Wood’s touching, if not wholly accurate, account of their first meeting and early days on the road through to their first break in television.

Their influence is still felt: Madame Tussauds in Blackpool last year put them into their wax figures exhibition. Two stage plays – David Pugh’s and Kenneth Branagh’s The Play What I Wrote and Bob Goulding’s Morecambe – won major awards, and author William Cook’s publications Eric Morecambe Unseen and Morecambe & Wise Untold were wonderfully produced works bolstering the Morecambe & Wise canon, which continues to build to this day. It’s truly remarkable considering that Eric died nearly thirty years ago and Ernie over thirteen.

The widows (Joan Morecambe and Doreen Wise) with the wax figure copies of their iconic husbands.

Out of everything in recent years, it is the made-for-TV film Eric and Ernie by Victoria Wood and scripted by Peter Bowker that touched me the most. It captured the era from which they emerged and, despite the liberties that film-writers have to take – and Peter Bowker is no different – it managed to give a good insight into Eric and Ernie’s upbringing. There was a warm portrait of Sadie, Eric’s enduring and supportive mother and the force behind the beginnings of the double act.

Sadie is a book in herself. Often erroneously portrayed as a single-minded showbiz mum, pushy and determined to see her son achieve greatness on the stage at all costs, and bereft when Eric and Ernie finally outgrow the need for her support, her true input and interest in the act was far less definable. As is often the case, the reality is more prosaic than the idea our imaginations conjure of what she should have been like.

If Sadie was ever pushy or determined to see her son succeed, it was because she recognised the balance between her son’s talent and his self-acknowledged idleness, and wanted him to take the opportunity that talent gave him to lead a better life than the one offered to him in 1930s northern England. She possessed surprisingly wide vision for someone of her station in life. And, as for supporting Eric on the road, she couldn’t wait for someone to come along (firstly Ernie Wise and, later, my mother Joan) and take him off her hands. Husband George at home must have felt he’d been widowed! So, instead of a feeling of sorrow at her son’s departure to new pastures, she embraced his going away with a huge sigh of relief and made a welcome and permanent return to Morecambe Bay and husband George. Her self-appointed mission to get her son off to a good start had been achieved. She never again involved herself with the workings of their act or their partnership.

Victoria’s film, however much amended for televisual purposes, still gave me a lump in the throat when watching it. It certainly prompted me to re-examine the act’s earlier years and lose myself if only mentally, while sitting on long flights or train journeys, in that time. My appetite had already been whetted prior to Victoria’s film by a trip I’d made four years earlier to Morecambe. I was researching that ‘last’ book on my father I referred to, and happily that led me to the last people still alive who had not only known Eric as a child, but either had attended dance class with him or been his mate at school. I’m still overwhelmed when I look back to my interviews with these now elderly contemporaries of my father who were part of his own humble beginnings. And what struck me the most was an observation that each one made to me, separate to the others’ knowledge – that they would have been more surprised if my father had not become the superstar he became than the fact that he did. Considering the social background and challenging times in which his childhood was played out, that was quite a passing observation to throw out there. And it was delivered with such intense honesty by each of them that I couldn’t help but recognise that it was no ‘with hindsight’ addition: they clearly had noticed that he was an unstoppable force, something we, his family, would come to understand, and which as a turn of phrase perfectly sums him up.

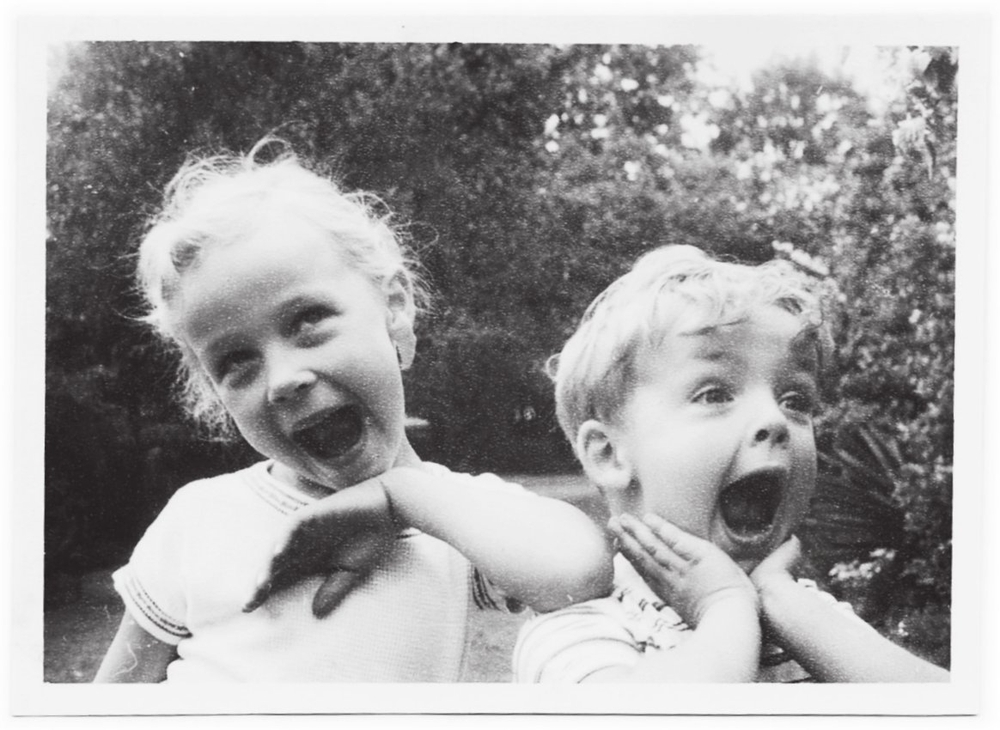

My sister Gail with her paternal grandfather, George. – GM

Perhaps it was that research period, as well as Victoria Wood’s film, that encouraged me to wallow in my father’s past – a past that was not mine, but which would form my own roots.

The idea that Eric and Ernie’s story began before the Second World War never fails to stagger me. They are remembered as arguably the greatest double act Britain has ever seen – comedians whose shows brought in on average around twenty-five million viewers. Yet, when Eric and Ernie set out on their path to showbiz glory, Charlie Chaplin was still making silent films in a very youthful Hollywood, Winston Churchill was yet to defeat Adolf Hitler and none of the iconic Beatles had been born. This gives a simple reminder of the sort of journey Eric and Ernie undertook, and the sheer graft involved in not only achieving what they did, but also the number of decades that their journey covered.

They were single acts working for Jack Hylton’s youth shows when they first decided to team up. In fact, August 2011 marked the seventieth anniversary of that historic moment when, for what would be the first of many, many times, they stepped out together under the lights of the stage. Their debut came at the Empire theatre in Liverpool – billed as Bartholomew and Wiseman.

In a world of instant gratification, it’s almost incomprehensible that they should have taken those first joint steps as fifteen-year-old youths and continued to do exactly the same thing (as massive stars) several decades later into late middle age. It must have taken tremendous dedication, particularly as their world had begun in the dying days of the variety halls when many of their friends and peers were sinking without trace as television increasingly slipped into people’s living rooms, eventually annihilating most other forms of entertainment – particularly the variety show tours.

My father’s profound observation on their ever-increasing success over the decades was that it happened because ‘we stayed together’. There is a great deal of truth to be found in that. TV mogul and family friend Michael Grade correctly picks up on the fact that they made it a rule very early on that no bickering that might naturally occur – or something worse – would be allowed to enter their relationship and distract them from their goal of being a very good double act. That kept their relationship intact, both personally and professionally. They were also two of the most talented people operating in show business, with a remarkable enthusiasm to rehearse, develop and hone their skills. As people who knew them both in a working capacity often tell me, they would still be thinking of ideas for a show they had already recorded, even though any change or addition was beyond question.

One of the other reasons they had such longevity is very obvious – they loved being entertainers. As a young lad, I stood side of stage when they were doing the summer season in Great Yarmouth in the mid-1960s, and again when they were touring their own live show a decade later. Each time they were about to step out onto that stage was like it could have been for the very first time back in Liverpool, such was the hunger and enthusiasm for their work. The money and the glory were only by-products of what they were doing as an act. The act was everything. My father would have performed alone in the family kitchen if that was what it took. Come to think of it, he sometimes did! Indeed, living with my father was like entering a twilight world of Morecambe & Wise. When you recall that a fair part of each Morecambe & Wise show was built around a studio-created apartment with bedroom, kitchen and living room, there are strong echoes of our home life. Fortunately, we were spared the rituals of his act – the bits of business such as the wiggling of the glasses and the slaps around the face; even he would have been driven insane by that. But if you picture a moment the comic you knew as Eric Morecambe in a more silent repose – some of the energy and mischievousness lurking within, while simultaneously under a tighter control than you are familiar with – you would get someway towards seeing what it was like living with this comedy giant.

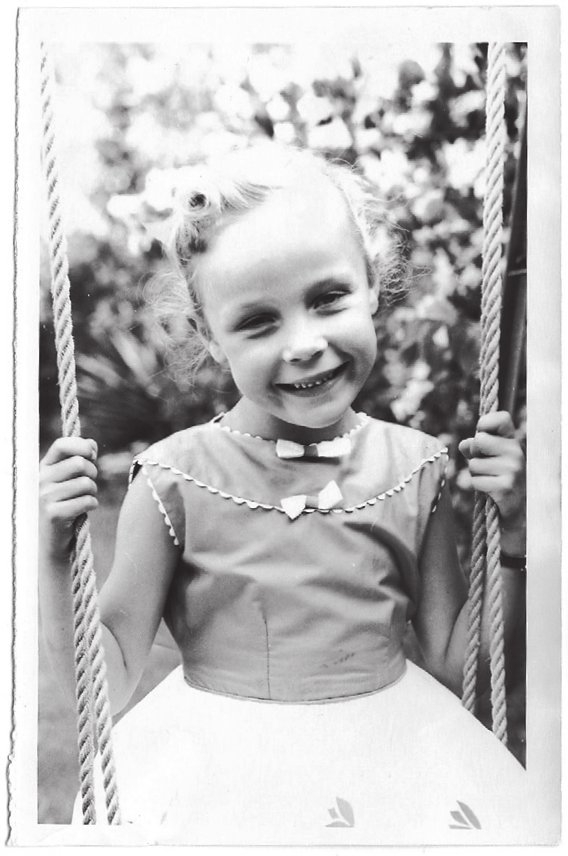

Eric’s daughter, Gail.

Gail and brother, Gary.

Morecambe & Wise’s journey in show business through the decades wasn’t solely about going from an unknown act to giant stars of television. There were many distractions on the way. The first being radio. Radio was around a long time before television forced it into a more ornamental pose in the household kitchen. For, as TV’s presence increased, radio gave up its place in the living room, where families had gathered to listen to their Prime Minister delivering sombre reports on the economy or the war effort, or enjoy light entertainment such as Workers’ Playtime and Band Waggon.

Eric and Ernie made their radio breakthrough on these shows and to my mind radio was the key to their developing such a powerful cross-talk act. They were working in theatre simultaneously, and travelling up to record the radio shows in Manchester on the Sunday between theatres, learning their scripts during those journeys. As it was radio and therefore (obviously) non-visual, all their skills were delivered solely through the voice. Not an easy thing for a double act, especially Morecambe & Wise’s, which increasingly would come to depend on those little looks and asides. Think of all the times Eric would turn to camera and say, ‘This boy’s a fool.’ Or the look he gives when André Previn calls his bluff with ‘But you’re playing all the wrong notes!’ Not easy trying to picture such magical moments through sound alone.

I recently listened to some 1940s and 1950s radio recordings of Morecambe & Wise we still have stored on original vinyl. What struck me was how well they dealt with this new medium – the way that they chose to compensate for the restrictions radio put on their act was to speak louder and faster! (Interestingly, decades later Eric gave that very instruction to their guest star Glenda Jackson during rehearsals for a BBC TV show.)

It shouldn’t go unmentioned that another reason Morecambe & Wise became so strong as a comedy force is the fact that they were allowed to. They were given something denied to most entertainers these days – time. We live in an era where instant results and success are obligatory to avoid being swept aside; nurturing is almost a forgotten notion, banished to the dead world of previous generations.

My father always said that he accepted he and Ernie had some talent, but even then – back in their heyday of the 1970s – he always balanced that by adding that they were so fortunate to have been in the right place at the right time to display their wares. They were a young double act beginning to blossom just as TV began to enforce its dominance over radio as the popular form of home entertainment.

It wouldn’t happen now, of course, for Morecambe & Wise didn’t succeed right away on TV – indeed, they were somewhat written off after failing to register in their first series outing in 1954, Running Wild. In our frenetic world of the new millennium, such a disaster would have meant no second chance. And their shows would be too expensive to make today.

Fortunately, during the 1950s and 1960s, they were allowed to fail on TV and then return a few years later in a new series, finally showing how well honed they had become as a partnership when given the freedom to perform in the way they wished to perform, not under the directives and orders of the TV station. That wasn’t the final package. Morecambe & Wise continued to further refine their personas and relationship through the ATV years 1961–67, and into the BBC years 1968–77. Development into the Morecambe & Wise we know and love to this day was mostly due to their BBC scriptwriter Eddie Braben dispensing with the traditional variety-hall hardness of the typical straight man, Ernie Wise, and the dumbness of the typical comic, Eric Morecambe. Ernie became the mildly flamboyant know-it-all with pretensions to being a playwright – ‘the play wot I wrote’ – and Eric became more streetwise and divisive with trace elements of Phil Silvers and Groucho Marx, on the one hand comforting the guest star, while destroying their credibility on the other. Perhaps they relaxed more and more into these new roles as time passed, but fundamentally there were no noticeable changes from 1968 until the end of their working lives.

During that twenty-year reign as kings of comedy, Morecambe & Wise went to Pinewood Studios and made three films in the mid-1960s, The Intelligence Men, That Riviera Touch and The Magnificent Two. But they never found the big screen to their liking and vice versa. Their comedy was always intimate – perpetual middle-aged men (even when they were young they appeared to be middle-aged men) sometimes almost whispering to each other in cross-talk banter to an attentive audience in the studio and living rooms across the land. Not so on the big screen. There was no audience reaction to comfort them, and they tended to disappear in lots of stunts – long before CGI could provide a degree of comfort. These 1960s films crop up on TV with surprising frequency, and I watch them with not a little nostalgia, remembering clearly my father going off to make them. And they’re really not that bad. They just aren’t that good, either.

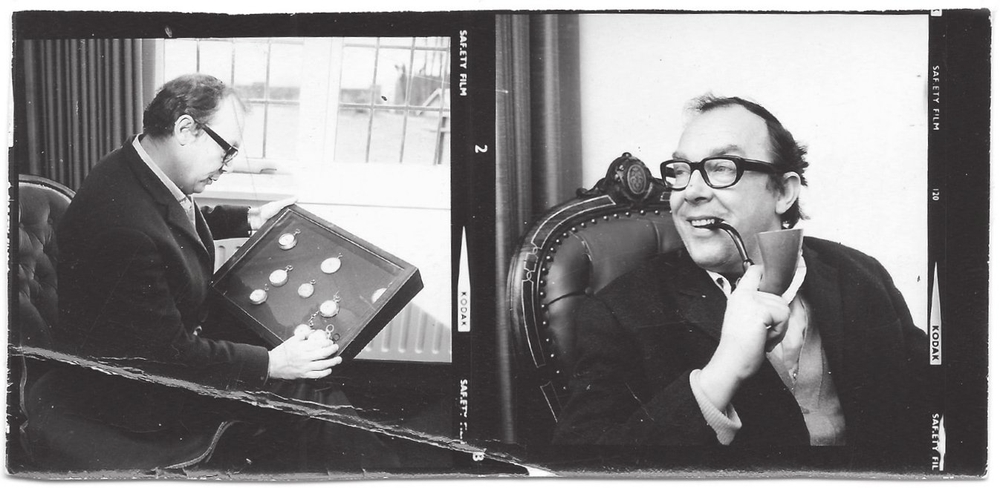

Eric with his favourite ‘Sherlock Holmes’ pipe. He had a matching deerstalker at one time, but sensibly hid it. He is also seen here with part of his watch collection, which grew into quite a serious passion and included rare wrist watches and fob watches. – GM

My sister Gail with our mother, Joan. – GM

My father was quite tense during this period. The Morecambe & Wise Show for Lew Grade’s ATV was steaming along nicely, but I sensed that, while the films were an irresistible challenge to the duo, and they were clearly on a roll after years of endlessly treading boards and performing at the end of piers, they were also a thorn in the side. Firstly, they were clearly out of their comfort zone, and, secondly, they were doing something that took a reasonable amount of their time away from the television studios where they worked best.

My father was always ambivalent whenever I referred to those Rank films of the 1960s. ‘Not really us’ and ‘they were all right, I suppose,’ were the most positive reactions. Other times it was, ‘They were rubbish really’ or ‘they tried to make us part of the Norman Wisdom vehicle’.

The only other film they made – and which in his final days my father managed to prevent from even being seen on TV for a number of years, let alone on a big screen anywhere – was Night Train to Murder. Personally I found it murder to watch, and it is nothing in comparison to my father’s own opinion. It really rankled with him. Opinion is split. Some people come up to me even today and describe it as a little-known gem. It’s a subjective issue, but what let it down from my viewpoint were the poor direction and editing, and the extreme slightness of the script. There is nothing edgy about the story – indeed, it’s quite turgid – and not enough gags punctuate what little storyline and action there is. Yes, it is a film in which they are supposed to play characters, but it was essentially a Morecambe & Wise film – that’s where the emphasis is and why the film got made in the first place, and with the expectation that their names brought to such a project.

If you look at one of the Morecambe & Wise TV shows, such as the routine with John Thaw and Dennis Waterman, you’ll see it’s filled with sharp gags, quick asides and splendid movement. Of course, TV is very different from cinema. There is no ad libbing as such when shooting a film, and many other characters – too many – were crammed into this particular production. That had always been the secret of Eric and Ernie’s appeal and the reason why they finally made it on TV. As soon as the cast of thousands disappeared, just leaving them and a guest star or two, their brilliance was able to emerge. And now, at the final hour of their working life together, they had unwittingly allowed themselves to be cajoled into something clearly marked as average before filming had even begun. And that’s what rankled with my father – his failure to have spotted that it wasn’t anywhere near right for Morecambe & Wise. At the time he beat himself up badly about it, but with the benefit of hindsight we now realise that there were reasons it slipped past his normally flawless judgement: the man was ill and not going to live much longer than another month or two.

There are two distinct eras to Morecambe & Wise – their living legend and their posthumous one. It’s rare in entertainment for deceased entertainers to receive the respect and glorification that accompanied them during their lifetimes. It could be argued that Morecambe & Wise are as successful today as at any time during their working lives. The TV shows and films continue to be repeated. The tributes, both verbal and practical, continue to pour in. ‘Bring Me Sunshine’ and their iconic skip-dance never go away and have appeared in adverts and greetings cards. Singer Robbie Williams even used it on one of his tours. He also had a very visible poster of Eric and Ernie on his stage set. Lee Mack uses a poster of them plastered to a door in one of his TV shows. Miranda Hart references my father constantly in her asides to the camera. Russell Brand, Jonathan Ross, Chris Evans have all referenced Morecambe & Wise within the last month of my writing this, so too the Daily Mail. The Sun used their image on the front page when announcing the coalition of Cameron and Clegg, plastering these politicians’ heads on to Eric and Ernie’s skip-dancing bodies. Though they are dead, their images and influence often reappear. As a double act, they are almost unique. Only almost because Laurel and Hardy are referenced the same way and, like Morecambe & Wise, live on in the public psyche.

The question I’m always asked in interviews, and which follows on to that observation just made, is: why do I think my father was and is so popular? I probably ask myself that question at least once a week (which shows how I fill my time these days). Both Morecambe & Wise had integrity, which is a key issue here. The pair went into the entertainment industry because they genuinely adored the working environment and were absorbed with the idea of entertaining the public. The public at large is not stupid – they can recognise a phony. Morecambe & Wise spent years entertaining that public with complete honesty, with no hidden agenda or smugness about them. And for the first two decades there was very little positive return. That they would go on to become a massive part of 1960s and 1970s TV entertainment was never guaranteed, but they stuck with what they knew and did their best. I believe the public appreciated this as they unwittingly became exceptionally familiar with these two characters that would never go away.

One of the clearest and earliest signs of their growing relevance as performers emerged when Eric nearly died at the young age of forty-two following a massive heart attack. The warmth of the public concern for his wellbeing was overwhelming. Their first comeback appearance was at the Pavilion Theatre, Bournemouth. They stepped out on stage with their usual enthusiasm to be greeted by a five-minute standing ovation. It prompted the thereafter oft-used expression by Eric to Ernie at the beginning of most shows – ‘Do we have time for any more?’

Two comic legends together. Ronnie Barker and Eric were good friends and great admirers of each other’s work. They often communicated by postcard.

Ronnie Barker once recalled the time he and his wife had the Morecambes over to dinner. On arriving, Eric enquired who else would be coming. Ronnie happily informed him. Eric turned nonchalantly to his chauffeur, Mike, and said, ‘Make it about an hour!’ – GM

Above all of this, and probably the most significant factor when attempting to analyse the longevity of Morecambe & Wise, is the indisputable fact that they were so wonderfully good at what they did. I still watch the André Previn sketch in awe. And, to give Previn his due, it is a three-man comedy success story. I’m glad to read that Miranda Hart, Jimmy Tarbuck and Victoria Wood go along with me in voting it their favourite piece of work by the duo. It was only one smallish part of the Morecambe & Wise 1971 Christmas show (which also included another memorable routine – putting the boot on Shirley Bassey), yet it ran almost the length of an episode of a sit-com. How wonderful that they were allowed to let it run its natural length without compulsory cuts and changes. In today’s viewing climate, where we are considered to have the attention spans of goldfish, the Previn routine would have had to go out at about three minutes!

I think the final piece of the puzzle of Eric’s personal longevity lies in his use of the camera. By turning away from Ernie and talking to the camera directly – stepping outside the performance and entering your and my living room – he was becoming a part of the viewers’ household, another family member. Miranda Hart was quick to spot the intimacy of that device, probably when she was a young girl watching their shows back in the seventies, and it has certainly been very well incorporated into her own series Miranda. Yes, she has reinvented the wheel, but in doing so she has made it her own. Comedian Harry Hill uses the same device in his TV Burp series.

Another question I’m frequently asked, and which takes us into very different territory, is: what was it like to have Eric Morecambe as a father?

There is no straightforward answer. People can behave very differently from day to day, so I can only give a general overview in my response. Firstly, whenever I think of my father – and that’s very frequently, probably every day – I at once picture him at the peak of his comedic powers (circa 1975) with a big grin on his face. That can’t be a bad image to have of someone thirty years after they’ve gone. I know the cynics amongst you will question why I should have an image that’s linked to his professional persona, but I honestly cannot recall much about his appearance in his final days when he was around the family home, as I had by then married and was living away. My mind’s eye has no doubt chosen the more comforting option of him at his incredible comic best, the image we still are fed today on our television screens. As I’ve more than implied, my father lived and breathed show business, so, while I certainly do have warm images of him at home sitting in his office or by the swimming pool, they tend to be overshadowed by his own personal love of being a comedy star and this was when he was happiest. I would go so far as to say that that is how he would want to be remembered. You must bear in mind that this was a man who would sit down and watch his own TV shows and fall about laughing – that’s how much it meant to him.

Growing up in the same house as Eric Morecambe was overall a very pleasurable experience. I’d worshipped him from the age of five. I very much doubt I perceived subconsciously that one day his career would play such a big part in my own life, but I know that once I knew what he meant beyond the family, and in doing so realised how unusual that made him, I never really stopped orbiting him. I watched his career go from strength to strength, and even for a short period indirectly worked for him when I was in press and publicity for his agent Billy Marsh at London Management. We both found the situation slightly comical come to think of it.

My father was a good, kind man with a fuse that had been shortened by the stress of his work and the expectations people invariably had of him. Perhaps his mistake was trying to live up to those expectations, but to be honest it was in his nature and upbringing to give his utmost and behave decently and properly, so he was never going to be one to knowingly let anybody down, or simply not care enough. Also, Morecambe & Wise were treading new ground – no one had really preceded them in moving successfully from stage to radio to TV. There was no blueprint on how to protect yourself from the bandwagon they’d climbed aboard as young kids. Consequently, I had a father at home who never could quite switch off or turn down anything work related. He could be very relaxed in certain situations – he loved watching TV, fishing, painting, reading, walking and bird watching – but the comedian in him was always lurking inside like a rogue spirit looking for that opportunity to burst out and perform with a quip or amusing observation. While much of that was in his nature, I did sense that some wasn’t – that he was more grimly holding on in case he switched off altogether and could never switch back on again. Indeed, he actually said that to me.

Eric removing Ernie from his will! – GM

Near the very end of his life, he was unable to make any major decision about his future – his health was clearly hindering his work. And yet, following meetings at the studios, he agreed to make more series of The Morecambe & Wise Show – surprising considering he had gone to those very meetings with the idea of announcing a partial if not total retirement. Presumably, all considered, he weighed up the fact that it had taken a long time for him and Ernie to get their big break, and that, having reached the stars, saying no to anything on offer was not a genuine option, even if it was a genuine thought.

The energy required for their shows, and required to become and then be Eric Morecambe – suppressed or otherwise – was quite exhausting to be around. And I’m sure it played a big part in his premature death, because, as comedian Rowan Atkinson observed, if it was tough to be around, imagine what it must have been like for him. As I’ve said before, and my mother has too, my father probably was, in a sense, a victim of comedy.

It’s interesting to me to recall how intense my father’s relationship with show business was. He wasn’t particularly interested in the socialising, partying side of the business, purely the business of making comedy shows. For while I genuinely feel his desire to be funny waxed and waned in his last year or two of life – and it’s no coincidence that his physical health was a frequently recurring issue by then – his desire to construct Morecambe & Wise shows never did. Hence, his inability to reject offers for more Christmas specials and a further series or two. Being funny was very tiring; creating and working on ideas with Ernie and their writers, working on which guest stars could be used in an appropriate manner and then, finally, recording the shows still ignited him – after forty-three years! Will any of our current crop of comedians have careers spanning over forty years? Not only is it doubtful but possibly unwise too. Having no precedent to speak of meant Eric and Ernie were making up the rules as they went along. Perhaps that is the difference these days – comedians form their own production companies and do things on their own terms: they know what is right and what is wrong for their physical and mental wellbeing, and have employed agents and secretaries to handle all the external elements of their business. Perhaps the extent to which today’s comics run their affairs has gone a little too far in the other direction, removing them from their ‘real’ personality. Certainly, the likes of Morecambe & Wise would never have even considered it.

The last twenty-five years have seen a huge change – the emergence of a self-preservation mentality, which overall should be considered a change for the better. My only mild discomfort with this more corporate approach to entertainment is when I sometimes watch a big-name stand-up doing his or her stuff at the Apollo Theatre or wherever, and find myself vaguely uncomfortable – and a tad disillusioned – that here is a millionaire production-company-owning entertainer pretending to be one of the general public. It grates with the reality of their situation and takes us back to that ‘P’ word – phony – that Eric and Ernie could never have been associated with.

With TV comedy now having a definite perceivable history, the new kids on the block have something to look on and use as a guideline. One of the clearest realisations, which comic actors such as Rowan Atkinson have proved, is that if the world finds you funny they will still find you funny should you decide to take time out and make infrequent returns. Indeed, making yourself scarce can have great positive benefits. People won’t forget you – a common phobia of my father’s if he took any length of time out, and he hardly ever did. In fact, his worry was twofold – worrying if the public would forget them, or if the public would be bored by the repetition of seeing them. Unnecessary self-imposed stress, we might say; yet that very stress is what created and gave us the Eric Morecambe we knew, loved and still love. It is a dilemma that can barely be solved by analysis.

I hope you enjoy the words and pictures in this book that celebrate a man who brought so much happiness to so many millions.

Gary Morecambe

Portugal, 2012