Chapter 9

Terror to the End

Some might have expected Charles Dickens to spend the summer of 1868 resting after his trip. Instead, he was planning a new, secret performance that would surprise all his friends.

At the end of the summer, his son Henry left for Trinity Hall at Cambridge University to study mathematics. Edward was going to join his brother Alfred farming in Australia.

Charles started his reading tour in October. In November, Charley became an editor at All the Year Round.

That same month, Charles unveiled the secret scene he was planning to perform. In Oliver Twist, a criminal named Bill Sykes catches his girlfriend, Nancy, trying to help the orphan, Oliver. In a fit of rage, he kills her. Terrified of what he’s done, he runs away and is later killed by the police. Charles was going to perform it all onstage.

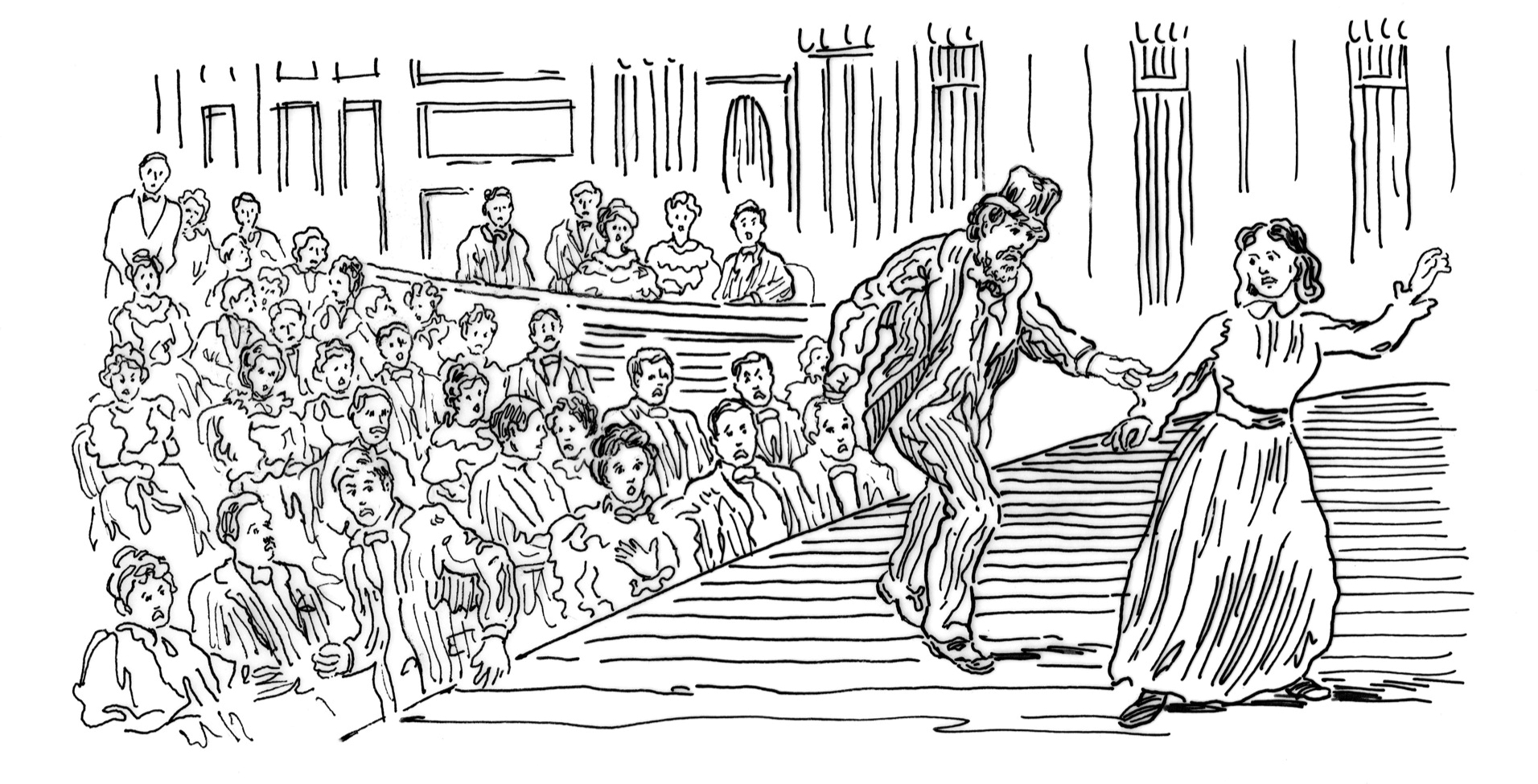

The scene was exciting and terrifying. Charles threw himself into the part of the evil Bill Sykes, whipping himself into a frenzy that was almost too real for his audience. In his own copy of the scene, Charles made a note to himself: “Terror to the End.” That’s exactly what he gave audiences.

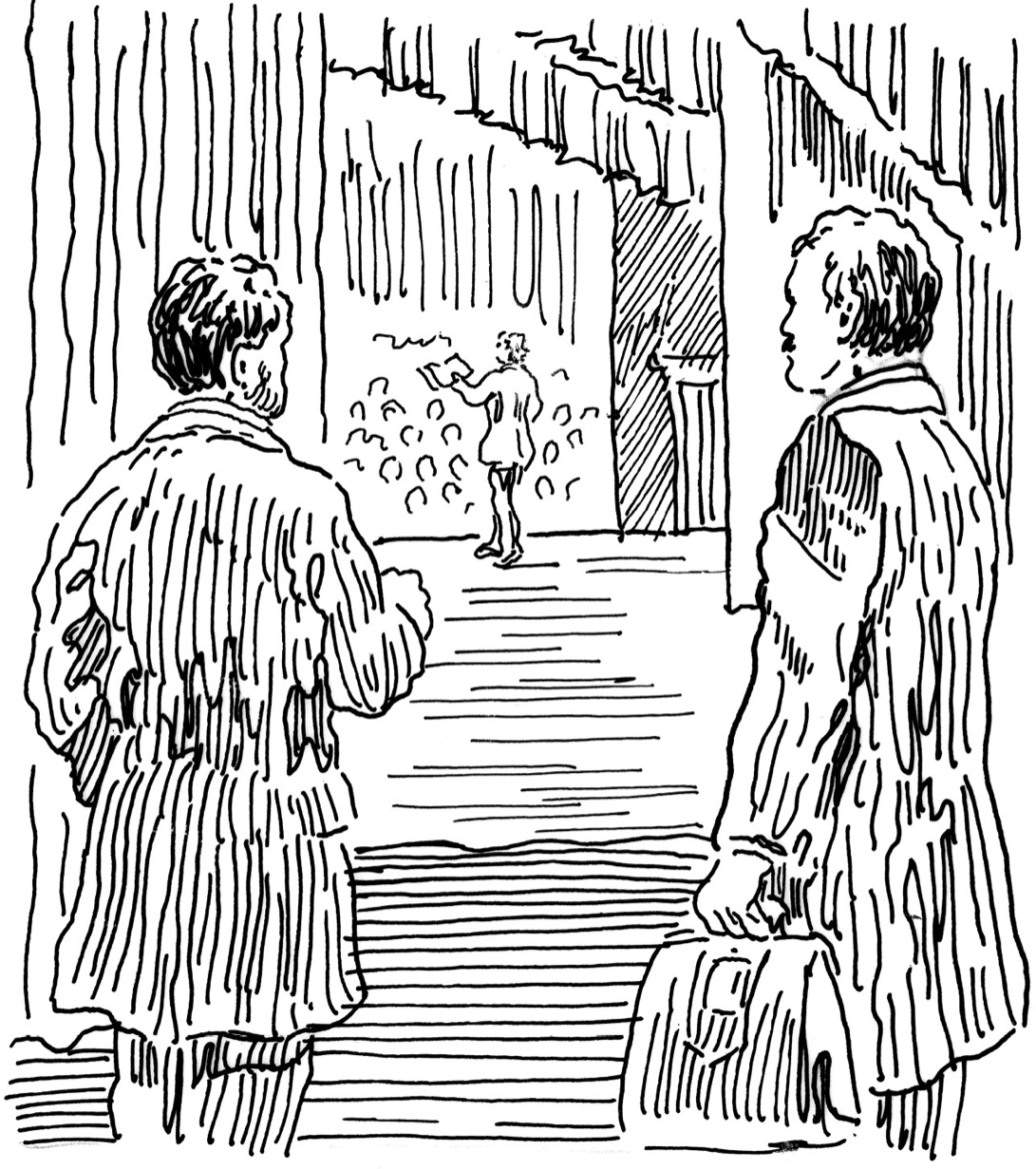

When it was finished, he was so exhausted he had to be helped offstage. But once he felt better, he wanted to do it again. Like any great actor, he loved the power he had over the audience.

His doctor ordered him to quit the tour completely, but Charles refused. The doctor told Charley Dickens to go to every performance. If his father seemed like he was going to fall down, the doctor had told him, “You must run up there and catch him . . . or, by Heaven, he’ll die before them all!” In April 1869, Charles took a break from the tour, but he wouldn’t quit completely.

While resting, Charles signed a contract with Chapman and Hall for a new book to be written in twelve parts: The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

For the illustrations in this new book, Charles hoped to hire his son-in-law, Charles Collins. Katey’s husband needed the money, but he was too sick to do the work. Charles had never liked Katey marrying someone so unwell. He later said that Charles Collins had just “collapsed for the whole term of his natural life.” For someone as active as Charles Dickens, Charles Collins must have been difficult to understand.

Charles’s foot was still painful, and one of his arms was numb. He had probably had a stroke, but ignored it. He couldn’t come downstairs at Gad’s Hill for most of Christmas 1869. One evening, he joined some of his family for traditional parlor games. In a memory game, everyone had to recite a list of items and add one more item for the next person. When they had been playing for a while, his son Henry said, Charles “had successfully gone through the long string of words, and finished up with his own contribution: ‘Warren’s Blacking, 30 Strand!’”

Charles said it with a strange look in his eye, as if the words had special meaning for him. Henry didn’t know what that meaning could be. Nearly fifty years later, Charles was still haunted by the shame of having worked in the blacking factory and still kept it a secret from almost everyone.