V

On the day of our house-raising bee when the neighbors were to help us build our cabin, we got up so early it was still dark out.

“Rob, do you really believe they will come?” Mama asked.

“Mr. LaBelle gave his word,” Papa said. “He’s a funny fellow, but an honest one, I believe.”

It was hard to imagine that by nightfall all the logs that lay scattered about would be a house.

The LaBelles were the first to arrive. The children jumped down out of the wagon and were everywhere at once. They ran down to see the pond, scrambled over the logs, climbed into our wagon to see what there might be to eat and tasted what they found.

Soon other wagons arrived. One family came a distance of twenty miles. The Indian whose daughter we had cared for came to help. “You go to a lot of trouble to build your house,” he told Papa. “We make our houses from a few sticks and some birch bark. When it is time for us to move on, we are not sorry to leave. But you could not leave a house like this one without looking back many times.” I wondered if he thought us foolish.

When the first logs had been laid, Mr. LaBelle, the most skillful man with an axe, was asked to be the corner man. He was the one to chop a notch at the ends of each log so they would fit one upon another. When the cabin grew to be as high as Papa’s chest it became too hard to lift the logs. The men set long poles at an angle from the top log to the ground, making a kind of slide. Then they shoved and shouldered the logs up the slide and into place.

This was hard work and they were loud in encouraging one another, sometimes saying words Mama thought it best I not hear, for she called me away to help prepare lunch. After we had all eaten, Mama pointed in the direction of the trees and said, “I believe that is the little Indian girl who had the measles. She has been too shy to eat with us, and her father has not seen to her. Take some of these corn cakes over to her, Libby.”

The girl was sitting so quietly I had not noticed her. Her long black hair was braided now, and shiny. She wore a calico dress sewn with bright-colored beads. Her dark eyes watched me as I walked toward her.

I handed her the plate of corn cakes and maple syrup and made some signs of eating, believing she would not understand English.

She took the cakes and said in very good English, “Corn cakes are good, but when we have a celebration we have better food—beaver tail and the hind feet of a bear.”

“Where did you learn English?” I asked, very surprised.

“When we lived a day’s journey from Detroit, I went to a school for Indians. The missionaries taught me English.”

“Why did you leave there?”

“Our chiefs sold our land. Now the government agents want to send us far away from our homes. If they catch us, they will make us leave.” She looked about her as though someone who meant her harm might be in the woods. After a moment she asked, “What is your name?”

“Libby. What’s yours?”

“Your name is not much. I am called Taw cum e go qua and I am of the clan of the eagle.” Fastened around her neck was a piece of rawhide holding a tiny silver eagle.

“Where did you get that?” I asked.

“The English gave it to my father for some skins,” she said. “They give better gifts than your countrymen.”

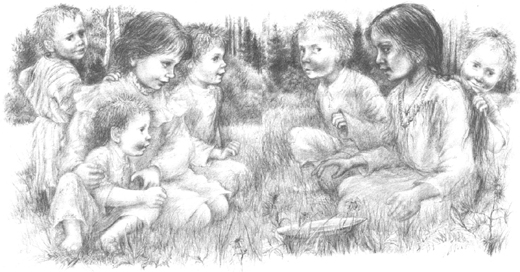

The LaBelle children had seen us and were now sitting in a circle staring at Taw cum e go qua, who with her high cheekbones and black hair and eyes was very pretty. They touched the beaded embroidery on her dress and moccasins and, had I not stopped them, would have taken the moccasins right off her feet.

When she finished the corn cakes, Taw cum e go qua put down the plate and stood up. Without another word she turned and began walking away from us. “Will you come back sometime?” I called. She didn’t answer or even turn around. In a few minutes she had disappeared among the trees.

The work on the cabin went on until it was nearly dark, and another meal was eaten before the last of the wagons left. “Some of these families will not get home until early morning,” Mama said. “How kind they were to help us.”

“Tomorrow I’ll begin fastening shakes onto the roof,” Papa said.

“And Libby and I can begin to muddy the chinks,” Mama said.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

Mama told me, “There are spaces between the logs where the wind and rain might come in and in winter, the snow. We have to push moss into all the spaces and then cover the moss over with mud.”

I was pleased to have some part in building our cabin and began to think of all the places in the woods where I had seen thick green moss growing. Thinking of the woods, I remembered Taw cum e go qua. When I had first heard it, I believed her name a strange one, but now I liked to say it to myself. It was like a small poem. Lying in bed that night, I thought I would like to be friends with the Indian girl, but I did not know where to find her. The Indians did not stay in one place. They would find a good trapping ground near a river or swamp, and when the animals had been caught, they would move on. Even the fields of corn they planted each spring were left on their own to grow. Papa said it took Indians only a few hours to build their houses. I supposed it would be nice to move about whenever you wanted, but I knew I would be glad to have the sturdy walls of the cabin around me when winter came. Although it was a warm summer night, I fell asleep wondering how Taw cum e go qua would stay warm when the snow began to fall.