FOLK ART OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH

When readers of The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture pick up the volumes called Geography or History or Literature, they can anticipate what kind of information they will find. The Folk Art volume, on the other hand, discusses art and artists whose connections to each other are far from obvious. Despite continuous proposals of alternate terms, including the more current “self-taught,” “American folk art” remains the most common name for the art of ordinary people with little or no academic training in art. This umbrella term preserves a notion of lasting cultural significance—that “the unconventional side of the American tradition in the fine arts” somehow captures the very essence of national identity. Understanding “southern folk art” requires attention to the artistic nationalism embraced by historians, intellectuals, and artists during the first half of the 20th century, to the South’s own regional patriotism, and to the South’s complex relationship to national patterns.

The concept of folk art as expression of national identities did not originate in the United States but had its roots in 19th-century Europe. Although ordinary folk have always made art—in all places and in all times—the term “folk art” first appears in print in 1845. Even then the term was invested with political meaning. Writing to promote German nationalism, the author of an essay on German wood carving praised peasant art—Volkskunst—as being a holy art, “rooted in the soil of the fatherland.” In 1894 Austrian art historian Alois Riegl’s Volkskunst, Hausfleiss und Hausindustrie proposed folk art as both the expression of a cultural essence of a people and a preserver of regional and national identities during periods of social change.

Similarly, “folk art” entered the American vocabulary during a period of nationalistic fervor when American artists, many of whom had studied in Europe, were declaring their independence from the Old World. The artists, art dealers, and collectors of modern art who discovered American folk art during the 1910s and 1920s celebrated the power of art as an expression of national identity. In his 1910 essay entitled “The New York Independent Artists,” Robert Henri, whose Ashcan School was already painting scenes of working-class life, expressed the populist tenor of the time: “There is only one reason for the development of art in America, and that is that the people of America learn the means of expressing themselves in their own time and in their own land. In this country we have no need for art as a culture; no need of art as a refined and elegant performance; no need of art for poetry’s sake, or any of these things for their own sake. What we do need is art that expresses the spirit of the people today.”

Traditional American Folk Art. The writers, artists, art dealers, and collectors of modern art who “discovered” American folk art during the 1910s and 1920s embraced artistic nationalism, seized upon untrained artists as narrators of a homemade American identity, and claimed folk art as the native precedent for their own work. The abstraction of form, exaggeration, linearity, saturated blocks of color, limited palette, and immediacy that stemmed from folk artists’ individual solutions to the challenges of representation paralleled modernist aesthetics; for the discoverers’ quirky portraits of well-appointed gentlemen and prim New England ladies in outlandish headgear, improbably faux-grained furniture, bombastic ships’ figure heads, exaggerated cigar-store figures, elegantly stylized decoys, earnest girlhood samplers, and other such work revealed the remarkable resourcefulness of folk artists who followed their own paths. This myth of the independent artist in a democratic society was, of course, a version of the myth of the self-made man whose self-reliance and self-discipline served himself, his family, and his nation.

Interpretations of American history that emphasize commonalities and gloss over conflict have been a mainstay of American thought. Every schoolchild learned that European settlers who arrived in search of liberty could easily become self-made men enjoying a “comfortable sufficiency.” For the discoverers of folk art, New England folk portraits, surely the most common examples of 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century folk art, became icons of American self-determination. The discoverers relished the self-taught artists’ careful renderings of conventional signs of prosperity, such as jewelry, property, or dress, as well as their penetrating representations of character. They likewise admired self-taught artists’ idealized landscapes of New England’s cultivated fields and pleasant towns and embraced these and other New England creations as emblems of a simpler, bygone era free of war, economic insecurity, and social unrest.

During the first decades of the 20th century, a number of modernist artists became collectors and devotees of American folk art. Sculptor Elie Nadelman amassed a considerable collection of American folk art and in 1926 established a short-lived folk art museum on his property in Riverdale, in Bronx County, N.Y. Other modernists who sought out folk art were Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth, whose own works include images of folk art and demonstrate their appreciation of folk art’s spare renderings of the American scene. Perhaps more significant in introducing folk art to the New York art world were artists Marsden Hartley, Bernard Karfiol, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Robert Laurent, and William and Marguerite Zorach, who came under folk art’s spell in Ogunquit, Me. There, collector and artist Hamilton Easter Field decorated cabins he rented to summering artists with inexpensive homemade objects and paintings he had picked up at auctions and in antique stores. Excited by reports from the modernist artists working in Ogunquit, Holger Cahill, a freelance journalist, publicist, and Newark Museum staff member, and Edith Gregor Halpert, a dealer of modern art, were also visitors. These two soon traveled back roads in pursuit of folk art treasures. Halpert, who represented many of the Ogunquit artists as well as Sheeler and Demuth at her Downtown Gallery in New York’s Greenwich Village, established in 1931 the American Folk Art Gallery, the first commercial gallery dedicated to American folk art. Cahill, who served as Halpert’s adviser, introduced folk ark to the museum world.

Cahill, who had served as the publicity director for Henri’s Society of Independent Artists and who had visited open-air museums of folk culture in Sweden, Norway, and Germany, was an ideal advocate for American folk art. The catalogs that accompanied Cahill’s three seminal exhibitions remain classics. The first two exhibitions, which Cahill organized for the Newark Museum, American Primitives: An Exhibit of the Paintings of Nineteenth Century Folk Artists (1930) and American Folk Sculpture: The Work of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Craftsmen (1931), adopt conventional fine art categories “painting” and “sculpture” and demonstrate Cahill’s definition of folk art as “the unconventional side of the American tradition in the fine arts.” For Cahill, American folk art could never be the equivalent of European folk art, defined as the community-based crafts or material culture of discrete peasant groups, each with its own shared ethnicity, religion, construction techniques, and decorative conventions. In American narratives, there were no peasants. In fact, only a few American groups have created folk art in the European sense, like the Moravians, who established their own communities in Pennsylvania and North Carolina, interrelated families of potters who developed distinct local styles passed on through generations, or groups like Alabama’s Gee’s Bend quilters, whose remarkable vocabulary of form resulted from geographic isolation. Emphasizing formal qualities over cultural context, Cahill excluded the utilitarian work of craftsmen—by which he meant the “makers of furniture, pottery, textiles, glass, and silverware”—but included the inventive, idiosyncratic creations of “the rare craftsman who is an artist by nature if not training.” Cahill’s so-called folk artists were not members of a well-defined community but ordinary Americans: tradesmen, farmers, schoolteachers, dance instructors, physicians, housewives, middle-class schoolgirls, slaves and former slaves, sailors, and an assortment of others who made exceptional art.

Cahill was certainly aware that his novel, specifically American, definitions of folk art and folk artists were problematic. The titles of his first two catalogs label the creators both as “folk artists” and as “craftsmen.” In the texts of those two catalogs Cahill employs almost interchangeably such terms as “primitive,” “naive,” and “folk.” In the catalog to his third and final folk art exhibition, American Folk Art: The Art of the Common Man, 1750–1900 (1932), Cahill, who had joined the staff of the Museum of Modern Art, speaks directly to difficulties of giving a single name to the diverse art made by American artists with little or no academic training: “The work of these men is folk art because it is the expression of the common people, made by them and intended for their use and enjoyment. It is not the expression of professional artists made for a small cultured class, and it has little to do with the fashionable art of its period.”

“Folk art” became the most durable name for this art not only because Cahill was a fluent writer and well-known art world figure but also because Cahill and Edith Gregor Halpert had become advisers to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. A founder of the Museum of Modern Art and a prominent collector of modern art, Rockefeller had begun collecting folk art during the 1920s. While Rockefeller valued the art’s historical character, she was smitten, above all, by its aesthetic similarities to modernist art. Rockefeller’s collection of more than 400 works, almost all from the Northeast, continues to exemplify the traditional art of the United States. The 173 artworks featured in Cahill’s Museum of Modern Art 1932 exhibition American Folk Art: Art of the Common Man, 1750–1900 came from Rockefeller’s collection. Although the Museum of Modern Art’s sponsorship of this exhibition might have seemed unlikely to some enthusiasts of modern art, the exhibition was a runaway success, appealing to both the art world and the casual museumgoer. It featured two- and three-dimensional works, toured to six additional venues between 1933 and 1934, and thus introduced the work and term “American folk art” to a wide audience. Rockefeller’s subsequent 1939 donation of the bulk of her collection to Colonial Williamsburg resulted in further national recognition of folk art.

Cahill’s argument for the term “American folk art” and its adoption by prominent members of New York’s art world did not, however, enshrine the term. The urge to define folk art according to both aesthetic qualities and the artist’s social status led inexorably to the continuing dispute. The “term warfare,” as writer, editor, and collector Didi Barrett wittily named the continuing rancorous debates about terminology, began soon after Cahill’s important publications.

The term “provincial painting” interprets American folk paintings as less polished versions of English paintings and draws attention to the artists’ lack of mastery. This use of “provincial,” implying that all colonists immigrated from England and that American artists followed the specific aesthetic norms of a school of English painters, is clearly incorrect. “Provincial” cannot describe all of the artists Cahill, Rockefeller, and others called “folk.” The term “provincial,” however, does have some limited use, as it correctly describes the training and practice of some important southern artists like José Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza, Louisiana’s foremost painter during the Spanish colonial period, who arrived in New Orleans in 1782 from Mérida in Yucatán. Although details of Salazar’s training are unknown, his portraits reveal his familiarity with Mexican provincial styles and Spanish painting conventions probably learned in Mexico, a Spanish province.

Unlike “provincial,” the term “primitive” has become obsolete. The concept of “primitive art” emerged at the end of the 19th century as a label for all non-Western artistic traditions. Museums lumped together in single departments such subjects as Japanese, African, Oceanic, and Pre-Columbian art; some museums maintained this nomenclature and organization until the beginning of the 21st century, when recognition of the term’s ethnocentricity and outdated notions of racial and cultural inferiority made the term unacceptable. Inevitably, “primitive” implies that the artist himself or herself is ignorant and that the art is defective; applied to American folk art, the term perpetuates the notion of deficiency.

“Naive” is another troublesome label. This term entered the modernist lexicon as a description of the idiosyncratic works of artists like Henri Rousseau, whose lack of academic training gives their attempts at naturalism a childlike quality. Like “primitive,” “naive” is often an expression of racial, religious, and class bias. “Naive” has further connotations antithetic to genuine understanding of the art by self-taught artists: the association of “naive” with words like “cute” and “quaint” has allowed cynical makers of merchandise to reduce folk art to a style of décor.

The discovery of 20th-century self-taught artists during the 1960s and 1970s renewed term warfare. While many collectors, scholars, and museum professionals committed to traditional American folk art were happy to trace continuities between the newly discovered work and pre-20th-century genres such as quilts, weathervanes, and trade figures, other enthusiasts preferred to view the work of 20th-century self-taught artists in relationship to mainstream contemporary art. Museums, especially, bore the burden of redefining “folk art” or coming up with new terms for art created by 20th-century artists with little or no formal training. Herbert W. Hemphill Jr., a founder and first curator of the Museum of American Folk Art, now the American Folk Art Museum, after much consideration settled on “contemporary folk art” because, like Holger Cahill, he felt that “folk art” was still the most recognizable name. Hemphill and Julia Weissman’s 1974 Twentieth-Century Folk Art and Artists gave currency to the name. Robert Bishop, the Museum of American Folk Art’s director from 1977 until 1991, followed suit when he included contemporary artists in his 1979 book Folk Painters of America.

Since the 1970s, members of the folk art world have proposed new labels. Some have advanced portmanteau names to replace the general term “folk art,” while others have tried to formulate names for specific subgroups of artists or types of creation. “Visionary,” an attempt to describe the remarkable individualism of artists unbound by academic convention, may also convey the impression that a visionary is given to wild enthusiasms or delusions. Although inappropriate for the field as a whole, the term “visionary” does recognize the religious or visionary experiences that artists, frequently southern artists, recall as the stimulus to their art making. Visionary may also describe artists who envision new worlds.

Rarely applied to traditional folk art, except in the case of “faux folk,” is the especially pernicious term “outsider.” An infelicitous translation of art brut, originally proposed as a label for the art made by artists whose mental states freed them from cultural art norms, “outsider” is now employed indiscriminately not only to describe the work of artists with atypical mental states or makers of highly individualistic art but also to describe the art of poor people, black people, children, and makers who simply choose to call themselves “outsiders” or produce materials for an “outsider” market. The pathology and otherness implied by “outsider” renders the term untenable.

On the other hand, “vernacular,” a recent characterization of the work of black artists, is a precise and necessary term, as it acknowledges a distinctive visual vocabulary shared by African Americans. “Vernacular” confronts a once-dominant assumption that the experience of slavery erased connections to the religions, worldviews, and artistic cultures brought to America by those captured in Africa and enslaved in the Americas. Beginning in the 1920s, Melville J. Herskovits, the father of African American anthropology, undertook extensive fieldwork in Africa and the Americas and documented continuities of African cultures in the Americas in scholarly and popular magazines. This insight did not meet with wide acceptance until the 1960s and 1970s, when Africanists like art historian Robert Farris Thompson, with expertise in African art and culture, further documented African philosophical and visual continuities in the New World. The “discovery” of living black folk artists in the South during the late 1960s and 1970s and the groundbreaking 1982 Corcoran Gallery of Art exhibition Black Folk Art in America, 1930–1980 made African American and southern visual and cultural traditions a focus of national attention.

More recently, the two-volume Souls Grown Deep, published in 2000 and 2001, and edited by William Arnett and Paul Arnett, along with other books published by Tinwood Books, have provided access to critical evaluation and superb photographs of the work of 20th- and 21st-century African American artists of the American South, including African American artists who took southern culture with them as they migrated elsewhere. These publications have also drawn attention to 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century African American pottery, textiles, and sculpture. Archaeologists excavating 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century African American settlements have unearthed numerous material examples that demonstrate continuities between African creative traditions and 20th-century art making in the New World. Such discoveries as Colono ware, marked with the Kongo cosmogram, having survived the passage of time, the depredations of the southern climate, and hard use, document spiritual and aesthetic continuities. Research also reveals the interactions of European American and African American makers and paves the way for further inquiries into the traditional folk art of the South.

Although Holger Cahill’s “folk art” remains the most recognized name for institutions and a general audience, most advocates now prefer “self-taught.” Like “folk,” “self-taught” can describe artists from the 16th to the 21st centuries. Furthermore, “self-taught,” a term without class and racial connotations, explains why scholars, museums, dealers, and collectors display self-taught art from all centuries of American history side by side: the makers are all artists with little or no training in art. However, though “self-taught” is clearer and more inclusive than “folk,” it too requires amplification. Art school graduates do not only learn in classrooms but also teach themselves through making art.

Many self-taught artists have had no craft or artistic training; others have adapted technical skills learned at the side of a master craftsman or in a workplace to create individualistic art. A few painters and sculptors who acquired brief, haphazard educations in art or studied with local, sketchily educated or other self-taught artists simply had to trust in their own devices. Many, like colonial portraitist William Dering, have no doubt derived compositional and pictorial formulas from print sources; in Dering’s bombastic and comical circa 1740 portrait of George Booth, the young boy, dressed in wig and stylish clothing, stands between stone plinths holding busts of generously endowed naked women. Researchers have not found any version of such sculpture in colonial Virginia.

Other artists’ careers demonstrate further qualifications of the term “self-taught.” Some painters, both immigrants and native born, may have staked claims to educations or accomplishments they had not truly achieved. Although New Orleans portraitist Julien Hudson claimed to have received a complete education in miniature painting in Paris, France, his folky style owes little to academic conventions. Many less accomplished immigrant portraitists, who settled in America hoping to find success among unsophisticated patrons, soon taught themselves the simplified styles that American patrons often preferred. The itinerant artist known as Dupue or the Guilford Limner, thought to be an immigrant from France, employed a linear and simplified New England style for the watercolor portraits he painted for patrons in North Carolina and Kentucky during the 1820s. These portraits repeat the conventions of middle-class New England portraiture during the colonial and early national periods, lending clarity to the subjects’ presentations of self by using emblems of piety, success, and refinement.

Like their middle-class patrons, American self-taught artists can derive special satisfaction in being self-made, independent Americans. Joshua Johnson, for example, thought to be the nation’s first African American professional artist, may have enjoyed some exposure to works of the Peale family of Philadelphia and Baltimore or some brief, unrecorded training. In 1798, however, the Baltimore portraitist proudly advertised himself as a “self-taught genius deriving from nature and industry his knowledge of the Art; and having experienced many insuperable obstacles in the pursuit of his studies.” Johnson’s use of “self-taught” is the earliest known application of the term to art making, but the term was commonly used during the 1830s to describe any number of self-made men. English visitor Frances Trollope’s 1832 Domestic Manners of the Americans recounts her amusement at the phrase “self-taught,” which she reports “had met me at every corner from the time I first entered the country.”

At this point, after nearly 100 years of term warfare, no one has hit upon a term pleasing to all; but “folk art” still carries more meaning to more people than does any other label. Academics, institutions, and collectors know what they mean by the name; and while some new museum visitors may expect to see only traditional forms like quilts, more and more visitors expect to see a full range of works by self-taught artists. The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, opened in 1957 as the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center, collects 20th- and 21st-century work but still honors its major donor with the name she preferred. The American Folk Art Museum has retained “folk art” in its name through two changes. Established in 1961 as the Museum of Early American Folk Arts, a name that limited folk art to a period of creation and seemed to concentrate on utilitarian decorative arts, the institution became the Museum of American Folk Art in 1966. In 2001 the museum adopted the name American Folk Art Museum to indicate more clearly its mission to display American art from all centuries as well as art made outside the United States. Major generalist museums also continue to refer to works in their collections as folk art, even as they define folk art as the art of self-taught artists. Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, a leader in the folk art field, is the only generalist American museum with a curator of folk art; its department of folk art provides a dynamic model for other institutions. Most heartening is the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s recent establishment of the position of curator of folk and self-taught art.

Joshua Johnson, The Westwood Children, ca. 1807, oil on canvas, 41⅛″ × 46″ (Courtesy the National Gallery of Art)

The concept of folk art has, obviously, expanded tremendously since its formulation in the early 20th-century Northeast. This expansion has allowed scholars to claim new bodies of work and to refine perceptions of traditional folk art. Careful research into the art making of ethnic groups, into artists working in specific locales, and into reciprocal influences has also expanded the concept of folk art. Scholarship in traditional folk art has flourished; sophisticated, intellectually, and visually pleasing exhibitions and publications address artists’ aesthetic choices and elucidate cultural contexts that confirm Cahill’s assertion that folk art is a living form of unconventional expression. The explosion of interest in folk art that followed the discovery of living folk artists in the 20th century expanded the self-taught art world in previously unimaginable directions. During the 1970s and 1980s, art dealers, institutions, and collectors sought out and celebrated new artists. Not only did scholars, dealers, and collectors meet with artists, but they also had the opportunity to hear artists’ descriptions of their art, lives, and ideas. Intellectuals and experts in many academic disciplines contributed to a deeper understanding and appreciation of self-taught artists past and present. The extraordinary creativity of living African American artists made clear the contributions of both self-taught and academically trained black artists to American art. Interest in self-taught American artists naturally led to interest in self-taught art as a global phenomenon.

Remarkably, however, many people and institutions still define traditional American folk art as the 19th-century art of New England. To be sure, the early discoverers of “folk art” found most of their treasures in New England, New York, and Pennsylvania and patronized dealers in the region. Succeeding generations of folk art collectors from the Northeast sought out additional examples from folk art’s golden age before mass production. As these collectors, in turn, have become donors to major museums, the exhibitions and catalogs published by these museums tend to keep the focus on New England. And, despite an almost instinctual impulse to hail American folk art as a portrait of the entire nation, few have asked where the traditional folk art of the South might be.

Why is it so difficult to learn about—or even see—the portraits, quilts, weathervanes, samplers, and other forms of traditional folk art created in the South? A student of folk art today is more likely to be more familiar with the details of the careers and art-making practices of 20th- and 21st-century masters and southerners like Thornton Dial and William Edmondson than with the makers of the South’s masterpieces of traditional folk art: among many others, the singular, deservedly iconic portrait, circa 1815, of Jean Baptiste Wiltz, a duck-hunting Louisiana gentleman blacksmith, now in the Louisiana State Museum; lovely portraits of Louisiana’s free persons of color, including the exquisite self-portrait of free man of color Julien Hudson; the circa 1865 sampler stitched by Salem, N.C., schoolgirl Mary Lou Hawkes, whose depiction of high-stepping former slaves, based on stereotypical prints of Jim Crow, reveals this young girl’s reaction to abolition; colorful and beautifully proportioned 19th-century chests from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Tennessee; or Texas artist Samuel Chamberlain’s watercolor depictions of his dalliances with voluptuous Mexican maidens, vivid accounts of the Mexican American War, and other scenes of 19th-century frontier life. We have to ask why early dealers and collectors did not scour the South for additions to their collections. Were there no southern collectors? Why is there no museum devoted to the traditional folk art of the South? In short, we still have to ask, where is the traditional folk art of the South?

Where Is the South’s Traditional Folk Art? The history of southern folk art begins in the 16th century during the Age of Discovery, when European explorers arrived in and began to document New World scenes and colonial settlements. Because scholars identify the art making of Native Americans as fine art or simply as art, the South’s first folk artists were European men, some engineers or architects with training in technical drawing, some with no known training. Their paintings and drawings became part of a historical record held in colonial archives or sent back to Europe to satisfy curiosity about strange lands. These early works did not receive the attention of art historians for centuries. The obscurity of a colony’s early works is not uncommon; recognition comes only when writers and collectors decide that a region or nation requires a historical survey of its art. The works of self-taught artists often remain in the shadows, as chroniclers with nationalistic purpose almost always lionize accomplishments in the so-called fine arts. Fashions in art making, however, change from time to time; the modernist artists living in proximity to New York during the first decades of the 20th century who discovered American folk art happily rejected the academic American art previously put forth as America’s finest achievements in order to celebrate direct and appealing works of folk art. But the craze for folk art did not take immediate root in the South. Appreciation of the art made by ordinary citizens of the South still lags because of the South’s peculiar history and mythmaking. The history of the South’s traditional folk art is one missed opportunity for recognition after another.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the South held little attraction for advocates of folk art. Hot summers and poor roads discouraged collecting trips, as did newspaper reports of racial violence. The resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, accounts of the 1925 Scopes Trial, and memories of the 1915 Georgia lynching of Leo Frank portrayed a benighted South. H. L. Mencken’s 1920 essay “The Sahara of the Bozart” did not paint a particularly welcoming picture either. W. J. Cash’s influential 1941 book Mind of the South again painted a dark picture of the region’s racism, violence, and old-time tribal religion. Images of crushing poverty published in popular magazines enforced an assumption that southern culture was itself impoverished. The explicitly democratic assumptions of American folk art simply could not find firm footing in the South. Early collectors outside the South saw the region as “a negation of America.” As historian James C. Cobb further explains, Americans were supposed to be tolerant, peaceful, rational, enlightened, cosmopolitan, ingenious, moral, just, pragmatic, and prosperous. For the early discoverers of American folk art and others who have emphasized consensus history, the South was outside the national patriotic narrative of “independence and freedom.”

Although the certainty that ordinary people have made art everywhere and in all times was the first article of faith for folk art advocates like Holger Cahill, Cahill had included only a handful of southern objects in his three exhibitions of folk art, and his aesthetic and ahistorical approach had allowed him to avoid mention of the burden of southern history that must engage southern historians. Cahill was delighted to display an Edgefield, S.C., face jug, but he did not draw attention to African American artists or to southern racism. Cahill had little information about many of the objects labeled southern in his three folk art exhibitions and catalogs. Indeed, Cahill became an advocate for southern folk art only by accident.

In 1934 Abby Aldrich Rockefeller offered to lend part of her folk art collection to Colonial Williamsburg, whose restoration was supported by her husband, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Encouraged to save the decrepit colonial buildings of the former Virginia capital, Rockefeller had bought land and numerous colonial buildings, which he then moved to a tract stretching from the colonial governor’s mansion to the Virginia House of Burgesses. Officials of Williamsburg Restoration, Inc., charged with obtaining furniture, art, and other décor from Virginia’s colonial period, questioned the propriety of exhibiting Rockefeller’s 19th-century materials, almost all from the Northeast. Rockefeller called upon her old friend and adviser Holger Cahill to negotiate the loan. Cahill argued that the art of resourceful, self-reliant Americans was an important adjunct to Williamsburg’s mission. This argument mollified officials, but they suggested that, even so, a collection with few examples of southern folk art was not desirable. Rockefeller quickly agreed to send Cahill in search of southern folk art.

In 1934 and 1935, Cahill made hurried and haphazard collecting journeys throughout the South. Lighting down in Charleston, Savannah, St. Augustine, Miami, New Orleans, Nashville, and many stops in between, Cahill sought equivalents to the New England portraits, landscapes, weathervanes, trade signs, and other such creations he had named folk art. Cahill visited museums and historical societies whose holdings might give pointers on what art he might find. He visited antique shops, junk shops, and private collections. In Charleston, a center of southern culture in the 18th century, Cahill visited the Charleston Museum and the Gibbes Memorial Art Gallery, now named the Gibbes Museum of Art, where, among other things, he saw portraits by Jeremiah Theus and Henrietta Johnson, miniatures, ceramics, and embroideries. He found that graveyards in Charleston offered “a regular picture gallery,” with stones that equaled stones he had admired in the Northeast. Cahill wrote that he had gotten “a real haul” in Charleston. In Winston-Salem, N.C., he visited the Salem Academy, where he saw embroideries and memorial paintings made by Moravian schoolgirls, and the Wachovia Historical Society, where he learned of Frederick Kemmelmeyer. In Salem, he purchased four “school-girl type” works. During a visit to Richmond, where the Virginia Museum of Fine Art was under construction, Cahill became excited by the possibility of future collaborations but found little to purchase. Cahill saw colonial portraits in Florida and Louisiana institutions but had no luck in locating colonial art for purchase.

On his second trip to Columbia, S.C., a scout for antiques dealers took Cahill to visit Mary Earle Lyles, who was persuaded to sell The Old Plantation, one of the icons of American art history. He was delighted that he had managed to acquire the work for a mere $20. A rare depiction of the private lives of slaves, the painting by slave owner John Rose provides a detailed image of enslaved Africans performing a dance immediately understood as African derived. Since the 1970s, The Old Plantation has served to illustrate the presence of African cultural traditions in the Americas.

Cahill, however, like many who have since attempted to find traditional folk art in the South, was at times stymied by the scarcity of works on the antiques market and by owners who were not willing to sell. In notes prepared for Rockefeller, for example, he reports his difficulties in obtaining even one weathervane. The sellers of a number of works of art had little information about makers. The fine face jug Cahill bought in Nashville, Tenn., differs from jugs made in Edgefield, S.C., but cannot with any certainty be attributed to a Tennessee maker.

Although Rockefeller’s southern works, originally exhibited in the restored 18th-century Lowell-Paradise House at Williamsburg, impressed many viewers, including prominent southern museum professionals, Cahill had little time or inclination to draw attention to the work. He did not publish a catalog on the southern art he had collected, and the lost opportunity to challenge the common assumption that folk art was a creation of New England’s preindustrial golden age has undoubtedly had long-term effects.

Cahill’s close involvement with Colonial Williamsburg came to an end in March 1935. In August of that year, he became National Director of the Works Project Administration’s Federal Art Project, where he remained until 1943, when the program came to an end. The Federal Art Project, a relief program designed to provide work for artists who could not earn livelihoods during the Great Depression, established art centers in more than 100 towns and cities, engaged artists to produce murals highlighting local scenes for post offices, and created the Index of American Design, whose artists produced nearly 18,000 watercolor depictions of traditional arts and crafts that ordinary Americans had produced prior to circa 1890. These images of America’s material culture, undertaken to encourage a greater understanding of American iconographic imagery and the quality and variety of objects produced by American artists and artisans, were allocated to the National Gallery of Art. In 1950, The Index of American Design, edited by the index’s curator Erwin O. Christensen and with an introduction by Holger Cahill, made a selection of the illustrations available to the public. This book contained images of Hispanic art but gave scant attention to the folk creations of the South. Cahill realized this shortcoming. He explained that fewer artists lived in the South and that Federal Art Project fieldworkers in the South had enjoyed more success with offering art and theater activities at community art centers. He noted that, despite intentions to represent objects from all sections of the country, the index project had been most active in the Northeast. Thus, this publication made for another lost opportunity.

Southerners, of course, had created folk art for centuries, and many southern contemporaries of the early collectors of northeastern material and their successors cherished the works of self-taught artists. Southern collectors of works made before the 20th century, however, sought “antiques” such as quilts, portraits, and landscapes that might buttress the myth of an aristocratic past and assert their own claims to gentility and accomplishment. The legend of the Lost Cause, which celebrated the backward-looking romanticization of the Old South and the Confederacy, dominated generations of southern lives. Mention of racial conflict was taboo, and white supremacy became deeply entrenched in a racially segregated culture creating a society distrustful of critical thought and departures from traditional ways. Class differences in the region were taken for granted; and many southerners, black and white, could not aspire to middle-class status. Elite southerners feared the “common man” and turned a blind eye to the lives—and art making—of those living on the other side of class and racial divides. The collecting pattern that arose from racism and class prejudice favored decorative sentimental landscapes, still lifes, and portraits—preferably old portraits of ancestors. A tendency to hold onto family objects—even those with obvious aesthetic shortcomings—has greatly hindered the establishment of public collections of southern folk art and continues to frustrate scholars who cannot easily locate art or make judgments of quality. While the southern art collectors, academics, and artists who discovered 20th-century self-taught artists William Edmondson and Bill Traylor saw these artists through the lens of modernism, many southerners did not respond to the aesthetics of modernism. Their definition of art certainly did not include unconventional art made by ordinary folk.

Some collectors of “antiques,” however, sidestepped Lost Cause myths and instead devoted themselves to the discovery and recognition of creations made in narrowly defined locales. Indeed, a local-history approach was compelling; the South as we know it is a mosaic of areas settled at different times by diverse peoples. In geographic terms, the South expanded enormously between the late colonial period and the middle of the 19th century, the three centuries that early folk art devotees had proclaimed as the golden age of traditional American folk art. Between the colonial period and the mid-19th century, the South redefined itself continuously. In fact, defining the term “the South” is as challenging as defining “folk art.” In art-historical terms, for example, Maryland was a key southern landscape from the colonial period to the middle of the 19th century, when Maryland was more attuned to the South’s culture than to the Northeast’s. Artists practicing in Maryland exerted their influence in Virginia and the coastal South, and they helped establish the expectations of southern patrons.

During the golden age of American folk art, some sections of today’s South were neither English colonies nor possessions nor states of the United States. Louisiana, Florida, and sections of other southern states did not look to England or to former English colonies for artistic models but to the European nations that had claimed and settled them. After years of uprisings and military actions, Texas declared its independence from Mexico only in 1836 and did not enter the union until 1845. Thus, Texas, like Louisiana, inherited Mexican provincial artistic traditions. After soliciting white settlers from Europe, 19th-century Texas added European traditions to its artistic resources. In Texas and elsewhere, ethnic groups, for example, German-speaking immigrants to Virginia and North Carolina, brought Germanic visual conventions to communities they established. Twentieth-century scholars and collectors who approach “the South” in terms of today’s geography may not be familiar with Spanish, French, Mexican, or German artistic conventions and, thus, easily ignore or misread the provincial folk art of these regions.

From the 16th to the 19th century, large sections of the South were the country’s always-changing western frontier. In the territories granted statehood during the 19th century, an aspiring middle class with the means to acquire goods or commission portraits grew slowly. Some rural and small-town southern patrons, particularly in river and coastal cities, relied on itinerant artists. Opportunities for southern self-taught portraitists were limited, though, by the mid-19th-century introduction of photography. Makers of regional furniture and pottery found that their creations were replaced by industrially produced goods. Some portrait painters took up photography, while others, straining to replicate the naturalism of photography, produced stiff, strangely detailed portraits that did little to reveal the personality of the sitter. Some artists colored photographs with paint or collaged photographed heads onto painted bodies. These awkward portraits, which can give the impression that the 19th-century South was a haven for talentless artists, demonstrate the impact of social and economic conditions on southern art making, and especially on portrait painting in the mid-19th-century South. The frontier heritage of the South’s inland areas and the brief careers of artists made redundant by photographic processes discouraged the formulation of an all-embracing southern portrait style.

Pride in locale, however, has fostered intensive research as well as the founding of museums and historical societies with a local, state, or regional focus. This antiquarian approach has preserved art and gathered information about the lives and times of art makers. For folk art historians, an antiquarian approach has been felicitous, as works of art that did not adhere to fine art principles in fashion when collected or those that referred to social problems were nonetheless seen as valuable documents. The antiquarian approach also meant that collectors and institutions often brought together local furniture, pottery, textiles, birth certificates, and many other creations called “folk art” in northeastern collections as integral elements of a particular cultural context. Southern scholars steeped in cultural context and respectful of the intents and achievements of ordinary folk also recognized the aesthetic qualities of works of art originally collected for their historical meanings. These experts in local history and culture became the discoverers and pioneer collectors of traditional southern folk—even if they did not adopt the term “folk art.”

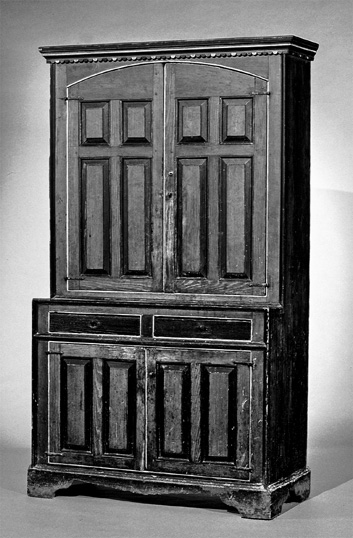

Although not the first collector/scholar to identify regional styles, Paul H. Burroughs, who published Southern Antiques in 1931, was one of the first serious writers to consider the South as a context for creative expression. Dealing only with furniture, Burroughs traced European roots of colonial furniture, furniture forms and styles brought to the South by later immigrants, and the emergence of stylistic types of furniture peculiar to the southern locales. Other major advocates for recognition of the South’s artistic achievements were antique dealers Theo Taliaferro (Theodosia Horton) and her son Frank L. Horton, who had begun to collect southern furniture during the 1940s. Horton redoubled his efforts after hearing of remarks made by Joseph Downs, curator of the Metropolitan Museum’s American Wing, at Colonial Williamsburg’s first Antiques Forum in 1949. Speaking on regional furniture styles, Downs had declared that “little of artistic merit was made south of Baltimore.” This declaration, indicating how little impressions of southern art making had changed since Mencken’s description of the South as “the Sahara of the Bozart,” became a challenge to collectors, dealers, and museum professionals. Horton and Taliaferro became founders of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Art (MESDA), dedicated solely to collecting, exhibiting, and researching pre-1820 decorative arts in the South. Founded in 1965 in Salem, N.C., MESDA displays the art making of the Moravians who established Salem and showcases more than 2,500 objects made by artists and artisans working in Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Other collectors and influential museum donors were Colonel Edgar William Garbisch and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, who began collecting folk art to furnish Pokety, the Cambridge, Md., hunting lodge they inherited after the death in 1940 of Mrs. Garbisch’s father, car maker Walter P. Chrysler. The Garbisches, who had furnished their New York apartment with French antiques and impressionist and postimpressionist paintings, decided that folk art would be more appropriate for the country house they were restoring. The couple collected voraciously, amassing some 2,500 examples of folk art, both masterpieces and less important works. The Garbisches acquired most of their collection from art and antique dealers in the Northeast but also patronized dealers in Maryland and Virginia. Taking the aesthetic approach established by the early collectors, the Garbisches did not always record provenances or information about the works they collected, and identifications of artists and circumstances of creation still require unraveling. While much of the Garbisch collection consisted of art made in the Northeast, the collection also contained exceptional works by such southern artists as Frederick Kemmelmeyer, Gustavus Hesselius, John Hesselius, Justus Engelhardt Kühn, and Joshua Johnson. In 1953 the Garbisches donated a large part of their collection to the National Gallery of Art, which refers to the art as “naive.” The couple also donated to 21 additional museums. The Garbisches’ donations to the Metropolitan Museum of Art form the core of that museum’s folk art holdings; among those holdings is their southern masterpiece, The Plantation, painted circa 1825, a marvelously stylized landscape with plantation house and shipping docks—all within a frame of grapes and leaves. Little is known about this work, one of the most celebrated of all American folk paintings.

Emphasis on local traditions also characterizes the research into southern folkways and crafts undertaken by anthropologists and folklorists. The study of folklore and the study of folk art both grew out of a desire to investigate the creations of ordinary people. Allen H. Eaton, a key figure in directing attention to Appalachian folk art as well as to folk traditions of ethnic immigrant groups, began a long association with the Russell Sage Foundation in 1920. Six years later he created the foundation’s Department of Arts and Social Work “to study the influence of art in everyday life.” In 1930 Eaton helped found the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild to promote Appalachian crafts—wood carving, textiles, pottery, furniture, and other domestic products—in order to provide income for families hard hit by the Depression. In 1934 Eaton organized an exhibition of crafts made by guild members for the first National Folk Festival. Eaton’s seminal book, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (1937), was the first major study of Appalachian crafts. Eaton’s interest in crafts made by living makers established the anthropological and folkloristic approach to the study of utilitarian handmade products.

For decades, folk art historians and folklorists have contested the meaning of the term “folk art,” each group passionately rejecting the other group’s interpretation. Folklorists define “folk” not as the common man or woman—writ large as “we the people”—but as members of a community defined by locale, ethnicity, or tradition. They define “art” as Eaton did—the communally shared manner of making rather than the aesthetically pleasing, exceptional creations produced by an artist with an individualistic vocabulary of form. One can say that folklorists emphasize “folk” while participants in the art world associated with dealers, collectors, art professionals, museums, and individual artists emphasize “art.” Participants in the folk art world define art as a transformative aesthetic experience and differentiate “art” from “craft.” In this art-historical view, skillfully made, attractive craft objects are nonetheless examples of goods made in multiples according to community expectations and therefore the antithesis of art. In recent years, the two groups have enjoyed some convergence; the notion of a continuum linking folk art and folk craft respects the skills and inventiveness of craftsmen as well as individual artists’ transformations of communal forms. Folklorists have begun to appreciate makers’ aesthetic intents and to recognize that aesthetic choices are in themselves meaningful. Charles G. Zug III has reported that many potters have seen no reason to make pottery with ornamentation or artistic profiles, whereas other potters have consciously created utilitarian pots with remarkable glazes and sculptural grace even though aesthetic considerations lower productivity and income. At the same time, the art world has come to appreciate the value of the field study that gives folklorists a depth of information about the work and communities they observe. Folk art historians can thank folklorists for the preservation of many creations ignored or unknown to past generations of folk art enthusiasts. Folklorists such as John A. Burrison have not only donated their extensive and exquisite collections to museums and study centers but have also expanded our understanding of “artfulness.” Zug’s appreciation of Brown family pottery with its exceptional height, fluid profiles, and refined sculptural presence argues for its inclusion in folk art museums and collections. Currently, folk art historians and folklorists share the conviction that art and craft are tied to broad cultural, historical, social, and political contexts.

Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, southern and national institutions added to their collections of traditional southern folk art and directed resources to their research programs. Among museums with local or regional emphasis and strong folk art holdings are the Historic New Orleans Collection, with a focus on New Orleans and the Gulf South, and the Louisiana State Museum, which holds many traditional paintings and other genres as well as works by 20th- and 21st-century artists. The Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library, formerly the family home of Henry Francis du Pont in Winterthur, Del., has a preeminent collection of American antiques and art, including extraordinary examples of traditional southern folk art.

No institution with a significant collection of southern material, however, was ready to respond to the remarkable surge of interest in traditional folk art occasioned by the 1976 celebration of the nation’s bicentennial. Southern museums had not yet taken on the task of producing guides to the study of traditional folk art in the South or organizing exhibitions that would gather excellent work from a number of institutions. Indeed, major efforts to highlight the folk art of the South came to fruition in New York. Publishing executive Robert Morton’s 1976 Southern Antiques and Folk Art was the first illustrated survey of decorative arts, folk art, and ornamented machine-made objects in common use in the pre-20th-century South. Morton’s volume with many color illustrations, however, did not accompany an exhibition or receive as much attention as it might have if issued by a major publisher. Robert Bishop’s pioneering Folk Paintings of America, published in 1979, was the first book to consider regional folk art within a national context; his chapter on the South contains 75 illustrations of paintings beginning with Jacques Le Moyne’s 1564 oil on canvas Indians of Florida Collecting Gold in the Streams. The book contains works by such painters as colonial pastelist Henrietta Johnson and 19th-century portrait artist Joshua Johnson and concludes with works by 20th-century self-taught artists, including Howard Finster and Mose Tolliver. Bishop’s book, which alluded to the biracial context of southern folk art, like Morton’s, did not accompany an exhibition and had less impact than it deserved.

Two well-publicized and well-attended exhibitions of traditional folk art held during the years surrounding America’s bicentennial and their lavishly produced large-format catalogs may also have drawn attention away from southern folk art. The 1974 exhibition The Flowering of American Folk Art, 1776–1876, organized by Jean Lipman and Alice Winchester for the Whitney Museum of American Art, showcased 239 objects from public and private collections across the country, and the catalog for the exhibition presented 410 illustrations selected from some 10,000 examples. But less than 5 percent of the works illustrated in the catalog came from the South, and the organizers had made little attempt to locate work held by smaller museums or private collectors. The distinctive portraits of middle-class southerners do not appear in this pivotal exhibition or in classic books on folk art, even though they share the intents and aesthetics of New England. The art of areas not colonized by the English and any mention of race did not fit into this bicentennial narrative. The Whitney’s second bicentennial era folk art exhibition, entitled American Folk Painters of Three Centuries, presented the works of individual folk artists chosen to represent the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. This 1980 exhibition, organized by Lipman and Tom Armstrong, presented the work of only one artist who worked in the South—Pennsylvanian Lewis Miller, who painted lively watercolors that record his visits to Virginia. Though never intended as textbooks, The Flowering of American Folk Art and American Folk Painters of Three Centuries have served this purpose. As a result, these two books, widely available in libraries and in used book stores, continue to perpetuate the New England bias.

Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art, 1776–1976, another exhibition inspired by the celebration of the U.S. bicentennial, was the first major exhibition on both traditional and contemporary self-taught artists working in a southern state. The exhibition transformed conceptions of southern folk art. Accompanied by a catalog written by Anna Wadsworth as well as a film, the exhibition traveled in 1977 to the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences in Savannah and then to the Columbus Museum of Arts and Crafts in Columbus, Ga. In 1978 the American Folklife Center, under the direction of Alan Jabbour, brought the exhibition to the Library of Congress (where First Lady Rosalyn Carter and daughter Amy helped open the show). Sparked by the bicentennial and its celebration of the country’s heritage, shows like Missing Pieces expanded national consciousness of the folk art traditions of the South.

The first exhibition exclusively devoted to the traditional folk art produced throughout the South took place only in 1985. Organized by Cynthia Elyce Rubin for the Museum of American Folk Art, Southern Folk Art presented works illustrated in Bishop’s American Folk Painting as well as many remarkable works borrowed from institutions and private collections. Rubin’s catalog, with images of numerous works of art never before located or illustrated, remains the most significant presentation of the South’s 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century folk art. However, the ground-breaking exhibition did not receive the attention it deserved. The small museum, now the American Folk Art Museum, still receives fewer visitors than it should; and the catalog, offering description rather than cultural analysis, was less informative than it might have been. The exhibition did not travel. The museum’s pioneering attempt to introduce pre-20th-century southern material into American folk art discourse had little impact.

Southern Folk Art was not only the first exhibition presenting the South’s traditional folk art but the last. Still, since 1985, traditional southern folk art has received considerable attention. Fine monographs on southern artists have appeared, and institutions have worked to gather information on southern art making. MESDA supports an active research program, photographing and describing objects identified as southern and made prior to 1820. MESDA’s Object Database, a collection of approximately 20,000 images of southern-made objects, and the MESDA Craftsman Database, a collection of primary source information on nearly 80,000 artisans working in 127 different trades, are valuable resources for scholars of southern folk art. MESDA’s publications, including the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, have illustrated its holdings and encouraged inclusion of southern work in considerations of American folk art. Colonial Williamsburg’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum (AARFAM) has produced many well-researched publications, a remarkable EMuseum online catalog that reproduces and examines the folk art in its collection, and many exhibitions that present southern folk art within contexts of time and place as well as in the context of American folk art history. Winterthur, MESDA, and AARFAM also sponsor frequent seminars on specific aspects of southern folk art. The Magazine Antiques, with both general and academic audiences, has published numerous articles on the South’s folk artists; the now-defunct Folk Art Magazine, a publication of the American Folk Art Museum, published many articles with insights into southern art.

Books devoted to the history of southern art almost always include traditional folk art. Jessie Poesch’s The Art of the Old South: Painting, Sculpture, Architecture, and the Products of Craftsmen, 1560–1860 (1983) and Painting in the South, 1564–1980 (1983) with essays by eminent scholars are invaluable. The exhibition Painting in the South traveled to six museums in Virginia, Alabama, Mississippi, Kentucky, Louisiana, and New York. Several well-produced volumes devoted to the art of specific states have made important contributions. Patti Carr Black’s Art in Mississippi, 1720–1980 (1998) includes both traditional and contemporary folk artists. Another fine study with excellent color plates and many scholarly essays is Benjamin H. Caldwell Jr., Robert Hicks, and Mark W. Scala’s Art of Tennessee (2003). In addition to state books, southern states, such as Texas and Georgia, have published online encyclopedias that discuss the work of folk artists. Numerous books on folk or backcountry furniture, pottery, painting, gravestones, needlework, quilting, and other textiles have illustrated and examined the art making in individual states or specific regions of the South.

Scholars specializing in forms of folk art that demonstrate women’s participation in folk art making—quilting, embroidery, and other genres—have published a wealth of books that call special attention to the contributions of southern women; these well-illustrated scholarly books go a long way in correcting the assumption that the South produced little folk art. Under the direction of Shelly Zegart, Eleanor Bingham Miller, and Eunice Ray, the Kentucky Quilt Project, initiated in 1981, established a movement to document quilts across the country. Quilts, such as those that southern women created and raffled to support the health needs of Confederate soldiers, and quilts created to raise funds for the construction of Confederate gunships underline women’s involvement in political affairs. Surveys of needlework in printed books and online demonstrate pride in place and the special pride that women and girls took in their participation in the progress of education and refinement in established cities and in frontier territories.

Museums currently seek southern additions to their collections, closing gaps and refining conceptions of southern folk art. The High Museum of Art, for example, has added remarkable works of traditional folk art to its strong collection of contemporary self-taught art. More and more generalist museums call attention to the southern origins of their holdings in 16th-, 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century art.

Nonetheless, the traditional folk art of the South is underappreciated and offers many opportunities for research. Colonial Williamsburg decorative arts librarian Susan P. Shames’s 2010 The Old Plantation: The Artist Revealed, for example, provides an excellent model for the identification of unknown artists. A narrative account of her identification of South Carolina slave owner John Rose, the watercolorist who painted The Old Plantation, reveals this artist’s background and intents. Such investigations of original documents like censuses; birth, death, and probate records; and property deeds, undertaken for decades by scholars of Northeast and Eastern Seaboard folk art, are necessary to our understanding of the careers of southern painters. The compilations of portraits published by state chapters of the National Society of Colonial Dames of America as aids to genealogical research point the way to further identification of artists, their training, and practice. Recent compilations such as the survey of Tennessee portraits, now available online, document the large number of artists who worked in that state and reveal groups of portraits with strong stylistic similarities that suggest that they were produced by single or connected artists. Information about ownership gathered during the preparation of the Colonial Dames’ recent surveys further allow scholars to locate the many southern portraits held by local historical societies, historic houses, and individual owners.

The recognition of the South’s rich biracial culture has revolutionized the study of art making in the South. Black and white artists have pursued many of the same themes and reciprocal influences, now obvious, suggesting opportunities for future research. Folk art depictions of daily activities document the centrality of African Americans in southern life and are thus important resources in studying slavery. These paintings also call for investigations into artists’ experiences and intentions. A search for additional paintings of southern scenes and reexaminations of known work may further elucidate African continuities in southern folk art.

Anyone wishing to see the rich range of the South’s traditional folk art will travel widely. The South’s traditional folk art resides in museums located throughout the nation, museums with a local or regional focus, historical societies, genealogical societies, historic houses, churches, cemeteries, state archives, and private hands. We look forward to new discoveries and interpretations. We also look forward to a time when narratives of American folk art embrace the traditional folk art of the South and the South’s many complexities.

Contemporary Folk Art: Where Is the South Now? The concept of contemporary folk art entered the art discourse in the early 20th century in the work of three men—Holger Cahill, Sydney Janis, and Otto Kallir. In 1938, Cahill, the doyen of traditional folk art, organized the exhibition Masters of Popular Painting for the Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition surveyed the work of several contemporary self-taught artists, including John Kane, Joseph Pickett, Horace Pippin, and the lone southerner, Kentuckian Patrick Sullivan, alongside the art of 19th-century artists. In the show’s catalog, Alfred H. Barr Jr., MoMA’s director, described nonacademic art as one of the “major . . . movements of modern art,” on a par with cubism and surrealism. Cahill went on to argue that folk art did not belong only to the past but that “splendid examples of it are in existence, from the work of the earliest anonymous limners of 17th-century New England to the contemporary work displayed in this exhibition.”

In 1939 Otto Kallir, an exponent of German and Austrian modernism, who had escaped from Nazi-occupied Austria, established the Galerie St. Etienne in New York. Kallir, having a keen appreciation of folk art, soon became the dealer of the untutored artist Anna Mary “Grandma Moses” Robertson. The dealer arranged the 1940 exhibition The Farm Woman Painted, which was the elderly woman’s first public exhibition in New York, and launched Moses on her way to becoming an internationally known celebrity. In the 1940s and 1950s, Galerie St. Etienne gained a reputation for its inclusion of self-taught artists within the framework of modernism.

In 1942, Sydney Janis, an influential collector, dealer, and author, wrote They Taught Themselves: American Primitive Painters of the 20th Century, the first book to analyze the work of 20th-century self-taught artists. Many of the artists he showcased had been featured in Cahill’s 1938 exhibition Masters of Popular Painting, but there were some newcomers, including Moses and Morris Hirshfield, a retired president of the EZ Walk Slipper Manufacturing Company. Still hailed as a classic, the book established the foundation and parameters of the field of contemporary self-taught art.

Janis was, in fact, the first person to introduce the term “self-taught” in the conversation on modern art. Asserting that untrained artists could be found in every period of history, come from all walks of life, practice all kinds of vocations, and burn with creative zeal, he preferred the term “self-taught,” over “folk,” “primitive,” or “naive.” Because self-taught artists worked at a distance from academic norms, he argued that they were “spiritually independent” of the established art world. Janis also affirmed, just as Cahill had, that 20th-century self-taught artists were “worthy successors to our 18th- and 19th-century anonymous portraitists.”

In the late 1930s and in the early 1940s, everything seemed in place for a groundswell of support within the New York art world for the work of contemporary self-taught artists. Indeed, during this time two remarkable exhibitions of southern self-taught artists took place in New York. The earliest occurred in 1937 when sculptor William Edmondson received an invitation for a one-person show at MoMA. In 1935 Sidney Hirsch, who taught at the Peabody College for Teachers (now a component of Vanderbilt University) and had seen Edmondson’s carvings during walks around his neighborhood, introduced Edmondson’s work to the fashion photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe. Her wonderfully shot photographs of Edmondson, his work, and environs caught the eye of Alfred H. Barr Jr., MoMA’s director, who arranged for the display of 12 of Edmondson’s statues in the fall of 1937. This exhibition was the first one-person show featuring the work of an African American and a self-taught artist at MoMA. There was a good deal of press coverage, including articles in the New York Times and the New Yorker. Instead of drawing attention to his art, however, the reviews focused on Edmondson’s illiteracy and religious visions. In the following year, nonetheless, Barr showed Edmondson’s work in Trois siècles d’arts aux États-Unis at the Jeu de Paumes in Paris.

The second exhibition of a southern self-taught artist in New York presented the drawings of Alabama’s 87-year-old Bill Traylor. A former slave, Traylor created his drawings on the streets of Montgomery. In 1939 a local white artist, Charles Shannon, had befriended Traylor, providing him with art supplies and organizing an exhibit of his work at New South, a community arts center in Montgomery. Shannon photographed Traylor, collected his drawings, many on scraps of cardboard, and in 1941 took examples of his work to New York, where he showed them to Victor d’Amico, MoMA’s director of education. D’Amico organized a show for Traylor at the prestigious Fieldston School in the exclusive neighborhood of Riverdale in the Bronx. The press took no notice. D’Amico also showed the drawings to Barr, who chose several of them for MoMA’s collection and some for his own. However, Barr’s offer to pay Shannon only a dollar or two for each drawing outraged the southerner, who demanded the objects’ return. It would be more than 30 years before Shannon tried again to introduce Traylor’s work to the New York art world.

In the first half of the 20th century, the champions of nonacademic art—Cahill, Kallir, and Janis—were members of the art world’s elite. They made the work of untutored artists a focus of the American art world, identifying many major self-taught artists of the 20th century and laying down the basic framework of the field. Nonetheless, in the prewar art world of the 1940s, the window of opportunity for self-taught art soon closed. When Morris Hirshfield was given a retrospective at MoMA in 1943, critics scorned the exhibition, asserting that MoMA had passed over so-called legitimate artists in favor of a self-taught artist. In the scandal that followed, Barr lost his position as director. Many untrained masters of the 20th century slipped from memory. Only Grandma Moses, who was “relegated to a vast populist backwater” of greeting cards and calendars, remained in the public eye. The art world embraced abstract expressionism as America’s new form of creative expression. Contemporary folk art would have to wait for its rediscovery in the second half of the century.

In 1968 sculptor Michael Hall and art historian Julie Hall, living in Lexington, Ky., where Michael was a member of the University of Kentucky’s studio art faculty, finally tracked down carver Edgar Tolson. They already owned some of Tolson’s carvings, but they wanted to meet the backwoods preacher and mountain carver, who lived near the small town of Campton in eastern Kentucky. Later that year, when the couple was visiting New York City, they stumbled onto the Museum of American Folk Art, where they discovered an exhibition called Collector’s Choice. The two were immediately smitten with the show, and as they walked through the exhibition, they made a chance encounter with Herbert W. Hemphill Jr., the exhibition’s cocurator and one of the museum’s founding trustees. Hemphill asked if they would like to see more pieces. The Halls said yes and ended up in Hemphill’s apartment, which was full of artworks. The three spent hours talking about folk art and became fast friends. Michael returned the next day to show Hemphill photographs of Tolson’s carvings. Hemphill liked what he saw. He purchased his first Tolson—an Adam and Eve—in early 1969, and in the spring of 1970 Hemphill traveled with the Halls to Campton to meet Tolson. The work of self-taught artists was on the road to rediscovery.

Even before the Halls had met Tolson, the carver’s reputation had spread beyond Kentucky. Tolson, who had carved since childhood, began selling his works in 1967 through the Kentucky Grassroots Craftsmen, a cooperative that marketed local crafts. When, in November 1967, members of the Grassroots Craftsmen went to Washington, D.C., seeking ways to increase the coop’s profits, they visited the Smithsonian National Museum of History and Technology, now the National Museum of American History. There they met with Carl Fox, manager of the Smithsonian’s gift shop, and showed him Tolson’s work. Fox purchased the pieces outright, requested more, and in early December wrote the carver telling him the gift shop would like to mount a large sales exhibition of his work and inviting him to Washington. Tolson accepted, and in 1968 he went to the capital, bringing several works, including a tableau of Adam and Eve, a half-dozen dolls, and a large carved horse. He met with Smithsonian officials, appeared on television, and became the subject of an article in the Washington Post. Between 1968 and 1976, the museum showcased Tolson’s work and the carvings of Hispanic folk artist George Lopez of New Mexico in American Folk Craft Survivals.

Tolson’s visit to Washington was propitious. Folklorist Ralph Rinzler was just then organizing the second Smithsonian Folklife Festival, and he invited Tolson to participate in both the 1968 and 1969 festivals. In 1973, when the festival honored the state of Kentucky, Rinzler invited Tolson as a featured artist. The festival’s program carried a photograph of Tolson’s work. That same year—1973—Tolson was featured (along with Michael Hall) in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Biennial, an exhibition that presents artists whose work exemplifies the current state of American art.

Just at the time that artists, art collectors, and folklife scholars were discovering Tolson, Kansas painter Gregg Blasdell was scouring the countryside for what he called grass-roots artists. He was searching for a kind of art that “has no definition in art history: the term ‘grassroots’ is only the best of a number of inadequate classifications such as ‘primitive,’ ‘folk,’ and ‘naïve.’” Blasdell’s 1968 photo essay, which appeared in Art in America, pioneered the study of folk art environments and featured ones that would become fixtures of American contemporary folk art, such as Simon Rodia’s Watts Tower in Los Angeles and S. P. Dinsmoor’s Garden of Eden in Lucas, Kan. In the South, he documented Brother Joseph Zoettl’s Ave Maria Grotto in Cullman, Ala., and Stephen Sykes’s now defunct towering In-Curiosity near Aberdeen, Miss. In 1974 Blasdell’s research inspired Naïves and Visionaries, a landmark exhibition of environments at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, which relied heavily on photographic documentation.

Two unrelated but extraordinary events, one in Washington, D.C., and the other in New York, made 1970 a pivotal year for the history of contemporary folk art. In 1970, the Smithsonian American Art Museum acquired the contemporary masterpiece James Hampton’s The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nation’s Millennium General Assembly. Also in 1970, the Museum of American Folk Art held a wide-ranging and well-researched exhibition entitled Twentieth Century Art and Artists, which exhibited many remarkable works known only to a few. During the 1960s, when the Smithsonian Institution exhibited Tolson’s and Lopez’s art, the works were displayed as craft in a museum devoted to American history and technology. The institution’s influential Folklife Program celebrated the creativity of the common man and woman as the product of craft survivals. Emphasizing geographic or ethnic craft traditions that have endured over time, the institution contextualized the works of self-taught artists as craft and exhibited it alongside such objects as canoes, baskets, and utilitarian goods. By the end of the decade, however, staff members of the Smithsonian National Museum of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian American Art Museum) were reconceptualizing the creative production of self-taught makers as art.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s commitment to contemporary self-taught art began in 1964 soon after the death of James Hampton, a reclusive, soft-spoken janitor, born the son of a black itinerant preacher in South Carolina. What James Hampton left behind in the Washington, D. C., garage he rented was a stunning, three-tiered assemblage, composed of foil-wrapped cast-off pieces of wood furniture, jelly jars, light bulbs, flower vases, desk blotters, mirror shards, strips of metal cut from coffee cans, as well as paper, plastic, cardboard, conduit, glue, tablets, tacks, and pins. Labeled The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations’ Millennium General Assembly in Hampton’s own handwriting, the glittering gold and silver construction featured chairs, pedestals, and lecterns symmetrically disposed on either side of a majestic throne crowned with the words “Fear Not.” The garage owner, Meyer Wertlieb, discovered the assemblage after Hampton’s death, and, realizing the importance of Hampton’s radiant installation, contacted a newspaper reporter. The Washington Post announced the story on 15 December 1964, under the headline, “Tinsel, Mystery Are Sole Legacy of Lonely Man’s Strange Vision.” Soon thereafter, Harry Lowe, curator of exhibition and design at the National Collection of Fine Arts, visited the garage to see the astonishing assemblage.

The second momentous folk art event of 1970 was the New York exhibition Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists. Curated by Herbert W. Hemphill Jr., the exhibition, shown at the Museum of American Folk Art, was composed of the work of 50 self-taught artists. The works of William Edmondson and artists discovered by Cahill, Kallir, and Janis—Grandma Moses, Morris Hirschfield, and Patrick Sullivan—shared the spotlight with 30 newly discovered artists, many of them southern: Eddie Arning, Minnie Evans, Theora Hamblett, Clementine Hunter, Sister Gertrude Morgan, and, of course, Edgar Tolson. The Kentucky artist was also featured in the introduction to Hemphill and coauthor Julia Weismann’s subsequent book Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists, which expanded on the 1970 exhibition and featured 145 artists. Insisting that folk art was not a thing of the past, Hemphill’s ground-breaking work established contemporary folk art as a wide-ranging phenomenon, made its presence known in the broad context of the art world, and inspired countless folk art hunters to persevere.

The exhibition of Hemphill’s own folk art collection parlayed these pioneering efforts into a full-blown movement. Shown at 24 museums between 1973 and 1988, Hemphill’s collection geographically extended his vision. In 1976 the American Bicentennial Commission even sent it to Japan on a goodwill tour. Ultimately, the Smithsonian American Art Museum became the repository of more than 400 works from Hemphill’s collection, an acquisition marked by the 1990 exhibition and book Made with Passion: The Hemphill Folk Art Collection in the National Museum of American Art (1991).