Gee’s Bend

In antebellum times, the area tucked within a hairpin curve of the Alabama River southwest of Selma contained several cotton plantations and acquired its name—Gee’s Bend—from the best known of those estates. After the Civil War, ex-slaves in “the Bend” took the names of the Gee’s Bend plantation’s later owners. For example, the Pettways stayed on the land as tenant farmers. Geographically isolated, with little day-to-day influence from the surrounding world, the African American residents of Gee’s Bend created a distinctive island of culture replete with its own customs, religious traditions, and—incubating for several generations—patchwork-quilt aesthetic.

The Gee’s Benders’ pioneer-style existence—with its hand-built log cabins, mule-driven wagons, and nearly self-sufficient economy—was not insulated from fluctuations in the price of cotton, and during the Great Depression the Gee’s Benders were thrown into cataclysm. Their goods were repossessed along with their food stores and livestock; the population was on the brink of starvation when the federal government intervened, eventually establishing Gee’s Bend as a New Deal experiment that enabled locals to purchase land and acquire new homes and that founded an agricultural cooperative, a school, and a clinic. A long-term effect of these government programs (besides the famous photographs that Farm Security Administration photographers Arnold Rothstein and Marion Post Wolcott took of Gee’s Bend in the late 1930s) was that many townspeople left behind their status as tenants; the presence of so many homeowners allowed Gee’s Bend to endure mostly intact through the second half of the 20th century, when many other southern rural communities and their traditions dissipated or disappeared.

Among the cultural survivals in Gee’s Bend was its quilt tradition. Quilt making had long been a part of young girls’ preparations for womanhood, and children frequently apprenticed at the feet of mothers and other female relatives and friends. Eventually a girl would make her own quilt, incorporating skills of cloth salvage, design, and sewing. Gee’s Bend quilts were traditionally made from recycled clothing, primarily denims and cotton twills. A reliance on archetypal patterns, especially variations of the “Log Cabin” or “Housetop” designs of concentric squares, fed into the use of heavy, resistant fabrics and Gee’s Benders fundamental thrift to create an aesthetic reminiscent of minimalism—spare, austere meditations on elemental geometric forms. At the same time, many Gee’s Bend women measured themselves by their originality and flair as quilt designers, so the Gee’s Bend aesthetic brims as well with surprising juxtapositions and shifts of scale, color, and visual rhythm. The distinctive qualities of Gee’s Bend quilts—minimalism in tension with dynamism—fit into the spectrum of African American patchwork quilts: the loose “Gee’s Bend style” seems a fusion of the individual, the family, the community, and ethnicity considered more broadly—as well as including patterns and techniques that are shared with or borrowed from Anglo-American quilts.

In 2002 Gee’s Bend quilts found international prominence when they were the subject of a major exhibition, The Quilts of Gee’s Bend, that traveled to 12 American museums. A second traveling exhibition, Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt, premiered in 2006.

PAUL ARNETT

Lafayette, California

Paul Arnett, William Arnett, Bernard Herman, and Maggi Gordon, Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt (2006); William Arnett and Paul Arnett, eds., Gee’s Bend: The Women and Their Quilts (2002); William Arnett et al., The Quilts of Gee’s Bend: Masterpieces from a Lost Place (2002).

Gibson, Sybil

(1908–1995)

Sybil Gibson said that her sweet and colorful paintings of flowers and children were childhood memories. The sad and haunted portraits of women’s faces seem to portray the fears and anxieties of her tumultuous adult life.

Born Sybil Aaron in Dora, Ala., on 18 February 1908 to a well-to-do family, she was educated in Alabama, eventually receiving a B.S. degree in elementary education from Jacksonville State Teachers College. She married her high school sweetheart, Hugh Gibson, in 1929 and had a daughter, Theresa, in 1932. The couple divorced in 1935, and Gibson left her daughter in the care of her parents. She taught school in Alabama and then in Florida, where she married David DeYarmon, who later moved to Ohio without her and died in 1958. Gibson’s painting career began in Miami in 1963, after she had seen some striking gift-wrapping paper. She soon became so prolific that she painted up to 100 paintings a day. Many of the thousands of works she produced, however, were lost as she moved from place to place.

Gibson often said that she preferred to paint on paper she took out of the trash bin rather than on good art paper. Considering the volume of her output and the sometimes precarious state of her finances, her approach is understandable. Although Gibson painted on any paper at hand, including newspapers, she preferred to use tempera paints on damp grocery bags. Her delicate wet-on-wet technique stands in contrast to the bold painting often seen in the works of southern folk artists. In addition to tempera, Gibson also used oils, house paint, acrylics, and watercolors. Her subjects included still lifes, landscapes, flowers, birds, cats, children, groups of figures, and striking portraits of women. She also painted a number of abstracts. Her impressionistic work has been praised by art critics as lyrical and tender, and it has been compared to that of Milton Avery and Odilon Redon. Believing that art could not be taught but must come forth intuitively, Gibson did not make sketches of her proposed subject. She said that she let the paintbrush dictate both subject and technique.

In 1971 the Miami Museum of Art organized a one-woman show of Gibson’s work. The artist, however, never saw the exhibition. She had returned to Alabama to “study weeds.” Over 20 years, Gibson’s circumstances continued to deteriorate. She lived in a seedy hotel in Birmingham, in a trailer with her cousin in Florida, and then in a facility for the elderly in Jasper, Ala., which expelled her because of disruptive behavior. By 1981, when she moved into the home for the elderly, Gibson had stopped painting because of poor eyesight. In 1991 Gibson’s daughter, Theresa, rescued her and arranged for a cataract operation. Gibson then moved to a nursing facility in Dunedin, Fla., near her daughter. With her eyesight restored, she was soon back at work on new paintings. She died on 2 January 1995. Gibson’s work has been included in many exhibitions and is in the permanent collections of such museums as the American Folk Art Museum, the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Art, the Mennello Museum of American Art, and the New Orleans Museum of Art.

JOHN HOOD

New York, New York

John Hood, Folk Art (Winter 1998–99); Kathy Kemp and Keith Boyer, Alabama’s Visionary Artists (1994); Alice Rae Yelen, Passionate Visions of the American South: Self-Taught Artists from 1940 to the Present (1993).

Golding, William O.

(1874–1943)

William O. Golding, an African American seaman, created nearly 70 lively drawings of sailing vessels and ports of call while a patient in the Marine Hospital in Savannah, Ga., during the 1930s. Golding recounted that as a boy he was shanghaied, tricked aboard a ship, at the port of Savannah in 1882 and did not see his home again until 1904. After close to 50 years at sea and visits to far-off corners of the globe on a variety of vessels, Golding began making art in 1932. Glimpses of Golding’s life and experiences are found in two letters written to Margaret Stiles, a Savannah artist who organized recreational activities at the hospital. Stiles encouraged Golding to draw; provided him with pencils, crayons, and paper; purchased drawings; and sold them on his behalf.

Golding’s detailed, fanciful drawings largely depict exotic ports and sailing ships, many of which he apparently had seen or served on. His depictions of specific vessels include the USS Constitution, which visited Savannah in 1931, and the USS Nourmahal, once owned by John Jacob Astor. Occasional works, for example, a drawing of the Alabama, a Confederate vessel, commemorate craft that he could not have seen. Golding’s drawings usually include drawn frames and nameplates complete with screws, details suggesting that he was familiar with framed nautical paintings or reproductions.

Stylistically, Golding reinvents the marine painting tradition in personal terms. Like professionally trained marine painters, he is concerned with identifying details such as rigging and signal flags. Golding also relies on individualized conventions, however, such as lighthouses, buoys, and his signature detail, a vibrant sun resembling a compass rose bursting forth from clouds. In his images of ports, Golding captures the flavor of a place by exaggerating landmarks, labeling sites of interest to a seaman, and populating these scenes with tiny human figures. Golding depicts ports of call, including his hometown of Savannah and ports in China, the Philippines, Java, Newfoundland, Trinidad, Cape Horn, the Rock of Gibraltar, and England. Golding claimed to have visited many of these spots and wrote to Stiles that he could not draw Hawaii or Bali because he had not seen them.

Golding died in the Marine Hospital in 1943 during surgery, after which public interest in his work continued intermittently. A 1947 photograph in Town and Country magazine shows numerous works by Golding decorating the Manhattan apartment of socialite Margaret Screven Duke, a professionally trained artist and niece of Golding’s mentor, Stiles. Golding’s work surfaced again in a 1969 exhibition at the Miami Art Center, in a 1970 article in Art in America, and in the traveling exhibition Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art, 1776–1976. The artist has since been the subject of solo exhibitions at Georgia museums including the Telfair Museum of Art (Savannah) and the Morris Museum of Art (Augusta). His work is also included in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

HARRY H. DELORME

Telfair Museum of Art

Pamela King and Harry DeLorme, Looking Back: Art in Savannah, 1900–1950 (1996); Anna Wadsworth, Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art, 1776–1976 (1976).

Gudgell, Henry

(1829–1895)

Kentucky-born Henry Gudgell was a mulatto slave who spent most of his life in Livingston County, Mo., where he became a blacksmith and wainwright and sometimes worked as a silversmith and coppersmith. Gudgell is best known, however, as the skilled wood-carver of two beautiful walking sticks, one now in the Yale University Art Gallery and the other in a private collection in Kentucky. The cane at Yale is the best documented of the two works. Writing in a seminal 1969 essay titled “African Influence on the Art of the United States” in Black Studies at the University: A Symposium, Robert Farris Thompson, a scholar of the arts of the African diaspora, suggested that Gudgell probably made the cane in 1867 for John Bryan, an army officer from Livingston County. Fighting on the side of the South, Bryan was shot in the leg and crippled in the early years of the Civil War, at the siege of Lexington, Mo., in 1861. Handed down in the Bryan family from one generation to the next, the cane was cataloged and illustrated in 1940 for the Index of American Design, housed at the National Gallery of Art, and then sold to Yale in 1968. The provenance of the second walking stick, which was discovered in 1982 and attributed to Gudgell on the basis of style, subject matter, and technique, is unknown.

Both of Gudgell’s canes, approximately 3 feet in height, carry similar abstract and figurative motifs. The designs carved in low relief near the handles of each cane consist of serpentine grooves, circular bands, and diamond-shaped patterns. Crawling up the shaft of each is a tiny caravan of reptiles: a lizard leads the procession, and a tortoise follows. Both are portrayed from above. Bringing up the rear of the convoy is a coiled serpent that glides effortlessly upward. The cane in the Yale collection carries two additional motifs: a branch with a single leaf and the tiny figure of a man. Both are placed just below the turtle and across from each other on opposing sides of the cane’s shaft. The man is viewed from behind and positioned just above the snake’s head. Dressed in a short-sleeve shirt, trousers, and shoes, the figure grasps the cane’s shaft with his arms and bended knees.

The peculiar combination of reptilian motifs and the human figure on the cane at Yale led Thompson to consider the role of canes and walking sticks and the meaning of turtles, lizards, and serpents in African and African American art, folklore, and folk belief. Thompson established the African roots of Gudgell’s cane, situating it as the earliest known example of an African-derived visual tradition best known in the carved canes of coastal Georgia. In The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (1978), John Michael Vlach further explored this connection, discussing similar works not only along the coast of Georgia but also in the Georgia Piedmont and in Mississippi. Referring to Gudgell’s cane in the Yale collection, Vlach observed, “It is ironic, although not incomprehensible that the greatest piece of Afro-American walking stick sculpture should have been made in north-central Missouri, in Livingston County, over a thousand miles from the geographic focus of a black carving tradition.”

In “An Odyssey: Finding the Other Henry Gudgell Walking Stick,” published in Folk Art (Fall 2008), Alan Weiss, the owner of Gudgell’s second cane, updated and expanded Thompson’s findings. Weiss discovered that Gudgell was born in 1829 in Anderson County, Ky., that his 15- or 16-year-old mother was named Rachael, and that his owner and probable father was Samuel Arbuckle, a wealthy white Kentuckian. In 1830 Arbuckle left in trust to his daughter Elizabeth Arbuckle several slaves, including Rachael and her infant son. In the same year Elizabeth and her husband Jacob Gudgell Jr. moved their household to Missouri, where they ultimately settled in Livingston County. In the coming years Henry Gudgell became the property of various members of his extended white family. He married, raised his own family, obtained his freedom after the Civil War, purchased 22 acres of land in 1870, and apparently flourished as a master of the metal arts and a maker of carved wooden canes.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of Gudgell’s work is its connection with the healing arts of West Africa that survived in the traditions of the African American South. Thompson associated the conspicuous presence of lizards, snakes, and turtles on African American walking sticks, such as Gudgell’s, to the prevalent role of reptiles in African American folk medicine or what is known as conjure. He noted, for example, the existence in Charleston, S.C., of a carved walking stick embellished with an entwined serpent that was called a “conjure stick.” He also observed that, in the folk beliefs of African Americans in early 20th-century Georgia, reptiles carried a negative connotation, and he concluded that the presence of such animals on a cane may “constitute a coded visual declaration of the power of the healer.” Writing in an essay titled “Defining the African-American Cane,” in American Folk Art Canes: Personal Sculpture, Ramona Austin, art historian and curator of African and African American art, defined two major forms of African American canes, conjuring canes and walking sticks. “Conjurer and root or hoodoo doctor are names for a ritual specialist. This specialist manipulates canes to cure, protect, or afflict.” Austin went on to say that Africans and African Americans recognized reptiles, which are able to live in water and on earth, as mediators between the spirit and the living worlds. Conjuring canes are “mediums of contact to a spirit world that can affect the psychic and physical disposition of people and things in the nonspirit world.” Gudgell’s canes, which exemplify this tradition, may have been intended and understood as objects that invoked the power to heal.

CAROL CROWN

University of Memphis

Ramona Austin, in American Folk Art Canes: Personal Sculpture, ed. George H. Meyer, with Kay White Meyer (1992); Betty J. Crouther, SECAC Review (1993); Georgia Writer’s Project, Drums and Shadows (1940); Betty Kuyk, African Voices in the African American Heritage (2003); Regenia Perry, in Black Art Ancestral Legacy: The African Impulse in African-American Art, ed. Robert V. Roselle (1989); Robert Farris Thompson, in Black Studies in the University: A Symposium, ed. Armstead L. Robinson, Craig C. Foster, and Donald H. Ogilvie (1969); John Michael Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (1978); Allan Weiss, Folk Art (Fall 2008).

Guilford Limner (Dupue)

(fl. 1820s)

Although records show that itinerant portraitists worked in North Carolina and Kentucky between the 1770s and the mid-19th century, scholars have not yet discovered the name of the artist known as the Guilford Limner. This artist, active during the 1820s in the vicinity of Greensboro, Guilford County, N.C., and also in Kentucky, signed none of the watercolor portraits attributed to him. The artist did not advertise services in local newspapers as did many itinerants, and because newspapers did not report the visit of a female painter, it is unlikely that the Guilford Limner was a woman. Indeed, the only hints at the artist’s identity come from a letter by the granddaughter of a North Carolina client referring to “a traveling French artist” and a note on the back of the portrait of Mr. and Mrs. James Ragland of Clark County, Ky., that reads “taken August 1820 on Clark Co., Kentucky by Dupue.” The stylistic similarities between the North Carolina portraits and the Kentucky works are sufficient to attribute the portraits to a single artist or perhaps to an artist and a close follower.

The Guilford Limner’s watercolor portraits, more affordable than oil paintings, depict middle-class patrons who lived in a time of community growth and increasing prosperity. Whether the sitters were men, women, or children, the limner paid close attention to the subject’s faces, and even though almost all have rounded eyes, well-defined eyebrows, short straight noses, diminutive cherub lips, and contained expressions, the artist manages to differentiate subjects from one another. Sometimes the artist also personalizes the portraits by painting the patrons’ names within a cartouche or within the composition as though the name were a wall decoration. The number of commissions the artist received in Guilford County—some 30—implies that patrons were pleased with their likenesses.

The conventional settings of the portraits undoubtedly fulfilled the desires of relatively affluent middle-class patrons to document their worldly and spiritual successes. Just as the artist repeated a limited repertoire of stylistic devices to render faces, he also placed most of his sitters within conventional and well-furnished 19th-century interiors that may not reflect the actual possessions of the sitters or the décor of their individual homes but suggest their affluence. Wainscoted walls, Windsor chairs, faux-painted decorations, and carpets with exuberant designs all display middle-class comforts. The sitters’ dress likewise indicates social status, age, and gender roles. Men wear white stocks, waistcoats, and cutaway jackets, while women wear modest but fashionable clothing. The portraits of members of the four generations of the Gillespie family are excellent representations of social identities. Colonel Gillespie, “Gilaspi” in the artists’ spelling, has chosen to present himself in the uniform and high-feathered hat of a Revolutionary War officer. Margaret, Daniel’s wife, wears a ruffled cap, wide scarf, and dark dress to display the modesty and rectitude of a grandmother. The Gillespie daughters, Nancy and Thankful, wearing jewelry and slightly less concealing clothes and sewing or knitting, advertise their industry and piety. In the portrait of Robert Gillespie, the married son of Daniel and Margaret, the limner indicates the young man’s success as a farmer through an unlikely display of corncobs that lie upon a sitting room’s paint-grained table. Robert’s wife, Nancy Hanner Gillespie, sits beside an abundant arrangement of flowers. The youngest member of the family, John Patterson Gillespie, wears a dark suit and carries a book, both conventional emblems of a boy’s preparation for adulthood. Other portraits contain additional emblems of attainment and virtue. Men may sit at desks and review their account books. Women holding bouquets and children standing in gardens are conventional depictions that represent the children’s flourishing and their parents’ careful nurture. The Raglan portrait places the couple out of doors; a winding road leading into the distance may represent the extent of their property.

Works by the Guilford Limner, or Dupue, are held in the Greensboro Historical Museum and in private collections.

CHERYL RIVERS

Brooklyn, New York

Karen Cobb Carroll, Windows to the Past: Primitive Watercolors from Guilford County, North Carolina from the 1820s (1983); Nina Fletcher Little, The Magazine Antiques (November 1968), Little by Little (1984); McKissick Museum, Carolina Folk: The Cradle of a Southern Tradition (1985).

Hall, Dilmus

(1900–1987)

Dilmus Hall, an African American self-taught artist from Athens, Ga., is best known for his small- and large-scale sculptures created out of concrete and found or scrap pieces of wood and for his drawings executed in colored pencil and crayon. His subject matter includes simple, charming depictions of animals and humans, ambitious allegorical and religious narrative scenes, and important figures from local history.

Hall grew up in rural Georgia, born into a farming and blacksmithing family, one of more than a dozen children. During his childhood he sculpted birds and other animals, often out of flour mixed with sweet gum sap. Hall’s mother encouraged her son’s early artistic pursuits, but his hardworking father found little merit in them. Hall left the family home and found work on a road gang and in a coal mine. In 1917 he joined the United States Army Medical Corps and transported injured soldiers across the battlefields of France. This experience allowed Hall to view European art, memories of which inspired later sculptures.

After leaving the army, Hall lived in Athens, Ga., where he worked as a hotel captain, a waiter, a sorority house busboy on the local University of Georgia campus, and a fabricator of concrete blocks for a construction company. Hall was a deep thinker, a philosopher, and a man of fierce faith. He believed that the teachings and happenings in the Bible were never far from contemporary life. In the book O, Appalachia, Ramona Lampelle describes Hall’s speaking style as that of a backcountry revival preacher and quotes Hall’s Old Testament inspired insights on art making and daily life. Many works reflect Hall’s interest in exemplary heroes whose virtues reflect biblical precepts. The artist’s small concrete tableau entitled Dr. Crawford Dying, for example, is a tribute to the Athens-based 19th-century surgeon Dr. Crawford W. Long (1815–78), who first discovered the effect of ether and used it during surgery. Long was also one of the few white doctors of the time who cared for African Americans.

In the 1950s Hall began to gain local attention for his architectural adornments and “yard art” outside his small cinder block home. The work entitled The Devil and the Drunk Man depicts two life-size drunkards and the devil in an allegorical environment. Hall believed that the devil was everywhere, encouraging people to commit sins. Hall saw these sculptures as protections from the devil. Much comparison has been made between Hall’s art and the African American conjuring culture, a vernacular religion that mixes aspects of Christianity with African traditions of empowering objects. Hall was drawn to, and believed in, the power of objects and symbols, although he was unaware of their African cultural allusions. To illustrate this point, Hall’s oeuvre includes sensitive and powerful depictions of the Crucifixion, many of which use a simplified, tripartite, y-shaped cross. This symbolic shape closely relates to a root sculpture constructed of a twisted branch, scraps of wood, metal, nails, and paint (ca. 1940), which Hall always referred to as his personal emblem.

In the 1980s, Hall’s work began to receive wider recognition when its originality and iconographic content became better understood. The High Museum and the American Folk Art Museum include Hall’s work in their collections.

JENINE CULLIGAN

Huntington Museum of Art

Paul Arnett and William Arnett, eds., Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South, vol. 1 (2000); Chris Hatten, Huntington Museum of Art: Fifty Years of Collecting (2001); Ramona Lampell and Millard Lampell, O, Appalachia: Artists of the Southern Mountains (1989); Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco, American Vernacular: New Discoveries in Folk, Self-Taught, and Outsider Sculptures (2002); Lynne E. Spriggs, Joanne Cubbs, Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, and Susan Mitchell Crawley, Let It Shine: Self-Taught Art from the T. Marshall Hahn Collection (2001).

Hamblett, Theora

(1895–1977)

Theora Hamblett was born 15 January 1895 in the small community of Paris, Miss. Hamblett lived the first half of her life on her family’s modest farm in Paris. Her experience as a white woman growing up and living in the impoverished rural South was typical of her times, with the exception that she never married or had children. From 1915 to 1936 Hamblett taught school intermittently in the counties near her family home. In 1939 she moved to the nearby town of Oxford, where she supported herself as a professional seamstress and converted her home into a boardinghouse.

Hamblett began painting in the early 1950s, fulfilling an interest in art that had begun in her youth. Although she enrolled in several informal art classes and a correspondence course during her later life, Hamblett was largely self-taught. Her first paintings depict memories of her childhood, and she painted scenes of southern country life for the next two decades, culminating in a series of paintings about children’s games. Hamblett’s most unusual works are the over 300 religious paintings representing biblical subjects and Hamblett’s own dreams and visions. These paintings began in 1954 with The Golden Gate, later renamed The Vision. Today, this first painting is owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York; most of Hamblett’s religious paintings and many memory paintings were never available for sale and were bequeathed by the artist to the University of Mississippi Museum in Oxford.

Hamblett’s religious paintings and interpretations of her dreams and visions were firmly rooted in her personal religious history. The popular, transdenominational southern Protestantism practiced in the churches, revival meetings, and hymn sings Hamblett attended in and around Paris, Miss., all emphasized the possibility of unmediated encounters between God and communicants, usually taking the form of visionary or dreamlike experiences. Church services were often structured around testimonies in which the worshipers described these experiences, and hymn lyrics regularly referred to them. Hamblett’s vision and dream paintings bear structural similarities to traditional testimonies, and many of her paintings employ images from the popular southern hymnody.

Hamblett’s aesthetics and working methods were also largely products of her background. The needlework skills she learned as a southern rural woman are evident in her art. Hamblett’s characteristic tiny brushstrokes of unmixed color resemble embroidery stitches, and many of her images suggest lacework and tatting. Her work provides a record of a vanishing regional history, and the complex associations of her religious paintings raise Hamblett from the status of an amateur to that of a significant artist of popular southern traditions.

ELLA KING TORREY

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

William Ferris, Local Color: A Sense of Place in Folk Art (1983), Four Women Artists (1977); Theora Hamblett, in collaboration with Ed Meek and William S. Haynie, Theora Hamblett Paintings (1975); Ella King Torrey, “The Religious Art of Theora Hamblett, Sources of Attitude and Imagery” (M.A. thesis, University of Mississippi, 1984).

Hampton, James

(1909–1964)

Working in an unheated, dimly lit garage in a run-down neighborhood in Washington, D.C., James Hampton, a janitor employed by the General Services Administration, crafted a dazzling, shrinelike sculpture: a huge altar radiant in gold and silver and touched in colors of wine red and green. Styling himself Director for Special Projects for the State of Eternity, Hampton fashioned The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly, a huge 180-piece construction. Made of cast-off objects such as old furniture, desk blotters, cardboard, jelly jars, and burned-out light bulbs, the Throne is ingeniously wrapped in gold and silver foil scavenged from store displays, wine bottles, cigarette boxes, and rolls of kitchen foil. From discarded junk, Hampton created a shimmering vision of dazzling light and color.

Born the son of a vagabond preacher or gospel singer, Hampton, who was raised a Baptist, claimed he had experienced religious visions throughout his life. He believed Moses had appeared in Washington, D.C., in 1931. Another vision in 1950 centered on the “Virgin Mary descending into heaven.” Drawing inspiration from his visions, he set to work on the Throne, which he may have intended to install one day in a storefront church. Today, however, Hampton’s creation is housed in the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It has been described by art critic Robert Hughes, writing in Time magazine, as perhaps “the finest work of visionary religious art produced by an American.”

Little is known about James Hampton. He grew up in Elloree, S.C., a small rural community just south of Columbia. Sometime in the late 1920s, Hampton moved to Washington, D.C., to join his elder brother. He worked at a variety of odd jobs and in 1942 was inducted into the army, where he served in a noncombatant unit as a carpenter. Returning to the nation’s capital in 1945, he rented a room in a boardinghouse. A year later, the General Services Administration hired him as a janitor. A quiet, soft-spoken, and unassuming man, Hampton never married, had few close friends, and maintained the same address and job until his death in 1964.

Sometime in 1950, saying he wanted a large work space, Hampton rented a garage in the northwest Washington neighborhood known as “Fourteenth and U,” near Howard University, the center of black business, religious activities, and nightlife. There, after his evening shift ended at midnight, Hampton worked on his astonishing liturgical assembly. As the focus of his symmetrical and bilateral design, Hampton erected on a 3-foot-high wooden platform an elaborate winged throne with a burgundy cushion and 7-foot-tall back panel crowned by the command “Fear Not.” Other furnishings, flanking it to left and right and situated in three parallel rows, recall the pulpits, altars, pedestals, offertory tables, and plaques of contemporary storefront churches. Hampton labeled many of the objects. Those on the viewer’s right of the throne refer to the Old Testament, while those on the viewer’s left relate to the New Testament. Other labels reference the millennium and the book of Revelation, the Bible’s most important prophetic book.

Hampton’s fabrication of The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly relates not only to the book of Revelation but also to early 20th-century fundamentalist beliefs known as dispensationalism. Teaching that the Bible is the literal word of God, this religious teaching divides history into ages or dispensations and promises the fulfillment of God’s prophecies in Christ’s return to earth, the millennium (a thousand years of bliss), and, ultimately, the New Jerusalem where God will reign forever. Calling himself St. James, Hampton may have seen himself as a modern-day counterpart to St. John, Revelation’s purported author. Like St. John, Hampton left behind a written text, which he entitled the Book of the 7 Dispensation of St. James. Each page is marked with the word “Revelation,” but the rest of the text is written in a script of Hampton’s own making that has not been deciphered. Even so, there is enough evidence to suggest that, like St. John’s text, The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly is intended to function as a visual prophecy of Christ’s return and God Almighty’s eternal reign.

CAROL CROWN

University of Memphis

Linda Roscoe Hartigan, The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts (1997), American Art (Summer 2000).

Harding, Chester

(1792–1866)

Born into poverty, Chester Harding was truly a self-made man. He worked as a chair painter, housepainter, sign painter, cabinetmaker, and tavern keeper before he took up portrait painting. At that time Harding had seen only the work of an obscure itinerant painter. By the end of his career, he had become an academic society painter in Boston hailed as a “marvel from the backwoods of America.” His success has been attributed not only to his inherent talent but also to his charming personality, confidence, and steadfast determination.

Born in Conway, Mass., in 1792, Harding began making “truthful likenesses” when he and his wife joined his brother in Paris, Kentucky, in 1815. After attempting his first portrait with sign paint, Harding was eager to leave behind his former careers. During this early period he learned by copying the portraits of itinerant but esteemed painters and attempting to replicate their techniques. Aware of his shortcomings, Harding managed to spend a few months during 1819 and 1820 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts “studying the best pictures, practicing at the same time with a brush.” Although Harding was dismayed to see that his portraits were greatly inferior to the polished works he had seen in Philadelphia, he commenced his career as an itinerant artist. Over the next thirty years he traveled extensively, visiting and revisiting cities such as St. Louis, New Orleans, Washington D.C., and Philadelphia to generate business. He also made two trips to Great Britain (1823–26 and 1846–1847) receiving many important commissions during these years that reflect the influence of Sir Thomas Lawrence. In 1830 Harding settled his wife and nine children in Springfield, Mass. He maintained a studio and gallery in Boston but also continued to travel in search of commissions. Harding’s gallery hosted many art exhibitions and was also home to the school founded by the Boston Artists’ Association. The artist died in 1866, leaving behind a lively personal memoir and numerous portraits of many prominent men and women that demonstrate his popularity and his natural talent.

From the fabled Daniel Boone, who sat for him in 1820, to Gen. William T. Sherman, whom he painted in 1865–66, Harding strove to accumulate a notable list of clients during his lifetime. No American painter of his generation could boast a more impressive list of patrons. They included three American presidents (Adams, Madison, and Harrison); statesmen John Calhoun and Daniel Webster; numerous governors, senators, and their wives; and fellow artist and close friend, Washington Allston. Regardless of their professions or positions, Harding chose to render his sitters with the truthful clarity that commonly characterizes the work of self-taught portraitists; in most of his paintings, a simplified plain background or drapery assures that the subject’s face is the center of attention. Harding’s full-length portraits again reveal his beginnings as a self-taught painter. Although these portraits may distort perspective and proportions, Harding had honed his skills to produce paintings that were accepted into annual exhibitions at London’s prestigious Royal Academy and at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

CAROL CROWN

University of Memphis

CHERYL RIVERS

Brooklyn, New York

Chester Harding, Margaret E. White, and W. P. G. Harding, A Sketch of Chester Harding, Artist, Drawn by His Own Hand (1970); Leah Lipton, A Truthful Likeness: Chester Harding and His Portraits (1985).

Harris, Felix “Fox”

(1905–1985)

Felix “Fox” Harris was born in 1905 in Trinity, Tex., a small east Texas sawmill town. As an adult, Harris lived in Beaumont, where he worked at various lumbering and railroad jobs, all hard physical labor. Like many other self-taught artists, Harris began art making late in life.

Harris’s inspiration for his dense, fantastic forest of shining metal sculptures and 20-foot-high totems came one night as he lay in bed. According to Harris, God appeared to him in a vision, holding in one hand a sheet of brown paper and in the other hand a sheet of white paper. God spoke to him of the sorrows and struggles of his life, which were symbolized by the brown paper. Laying that paper aside, He told Harris that his old life would also be laid aside and that he would receive the gift of new life symbolized by the white paper. As Harris put it, “God took nothing and made something.”

That phrase, “Take nothing and make something,” became the theme of Harris’s work. For more than 20 years, the artist took the broken and discarded objects of everyday life and transformed them into an environment alive with color and movement. He worked intuitively and confidently; and although the individual pieces are singular, the work as a whole conforms to a strong and consistent vision. His environment displays aesthetic preferences associated with other African American yard shows: flashing metal, circular objects like hubcaps, diamond shapes, and kinetic elements that indicate spirit and potentiality.

Although Harris was certainly familiar with implements that could have speeded his work, his tools were few and handmade. For his metal cutouts, the artist preferred to use what looked like an ordinary table knife that he had modified by flattening the handle with a ball-peen hammer and by sharpening the tip of the blade. He customarily made a stencil with pencil and paper, traced it onto the metal, and then painstakingly cut out the design by placing the sharpened knife tip along the drawn line and gently tapping out the figure with the hammer. He also fashioned a pair of wooden stilts and used them when working on the tall totems. He called them his “tom-walkers.” To see him, nine feet tall, striding through his forest on those tom-walkers was a heart-stopping, indelible sight.

Harris continued to work until his death in 1985. After his death, family, friends, and art collectors preserved a portion of the environment, moving it and installing it on the grounds of the Art Museum of Southeast Texas. Because of concerns about hurricane damage and deterioration, the environment was reinstalled inside the museum, where it is on semipermanent display.

PATRICIA CARTER

Beaumont, Texas

Ray Daniel (introduction), Patricia Carter, and Lynn P. Castle, Felix Fox Harris (2008).

Harvey, Bessie Ruth White

(1929–1994)

Using little more than roots, shells, and paint, visionary artist Bessie Harvey assembled a diverse cast of figures that appeared vividly before her mind’s eye. Biblical characters, African ancestors, mythological creatures, and episodes from African American history materialized under her touch with equal intensity. Each reveals the richness of her imagination, the depth of her spirituality, and her extraordinary gifts as a storyteller.

Born Bessie Ruth White on 11 October 1929, Harvey was the seventh of 13 children born to Homer and Rosie Mae White in Dallas, Ga. In her early 20s, she moved to Tennessee, briefly living in Knoxville and then permanently in nearby Alcoa, where she secured a job with Blount Memorial Hospital in order to help provide for her children and grandchildren. Although aware of her own creative gifts as a child, Harvey did not devote her full-time energies to making art until her late 40s. Seeking solace from life’s challenges, she found strength and comfort in her faith and also began to discern spirits in seemingly ordinary pieces of gnarled wood. Whorls and knots might indicate the eyes or a mouth of a biblical character just as an attenuated branch might suggest a serpent. In her makeshift basement studio, Harvey added paint, wood putty, shells, hair, cloth, and other items to each piece of wood in order to give vivid physical form to the spirit she perceived within. Her earliest creations tended to be small, simple figures decorated only with black paint, human hair, and shells or beads. Collectors began to recognize the raw expressive power of her strange, dark figures, and Harvey’s reputation soared by the early 1980s.

Troubled by local rumors that her work was the product of voodoo, Harvey, one day in 1983, burned the contents of her studio. After a few weeks of self-reflection, however, she went back to work with the newfound realization that her sculptures were important messages from God to a troubled world. Her works became increasingly large, colorful, and elaborate and enriched by glitter, cloth, beads, and jewelry. She also embarked on a loosely autobiographical series, Africa in America, which she intended as a teaching tool for children in her community. By the time of her death in 1994, the series included more than 20 sculptural dioramas depicting the African American experience and race relations during and after the era of slavery. Unlike Harvey’s earlier spirit sculptures, the works in Africa in America are highly descriptive and can be seen as carefully planned episodes in an epic narrative. However, they too reflect the artist’s ability to transform ordinary materials into objects of uncommon aesthetic power infused with moral concepts of universal relevance.

In 1995 Harvey’s work was chosen for inclusion in the Whitney Museum’s Biennial. Museums that hold Harvey’s works in their collections include the Whitney Museum, the Milwaukee Museum of Art, the American Folk Art Museum, the Knoxville Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

STEPHEN C. WICKS

Knoxville Museum of Art

Paul Arnett and William Arnett, eds., Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South, vol. 1 (2000); Alvia J. Wardlaw, Black Art, Ancestral Legacy: The African Impulse in African American Art (1989); Stephen C. Wicks, Awakening the Spirits: Art by Bessie Harvey (1997).

Hawkins, William Lawrence

(1895–1990)

William Hawkins, one of America’s most important African American artists, was a short, stocky man and a great talker. He was supremely confident and as exuberant as his monumental paintings and his lesser-known drawings. His principal subjects were animals, architecture, and narratives.

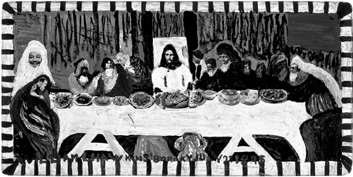

William Lawrence Hawkins, Last Supper #6, 1986, enamel on Masonite with collage, 24″ × 48″ (Collection of Robert A. Roth)

Hawkins was born in rural Kentucky. After his mother’s death when he was two years old, he, along with his brother, was raised on the farm of his affluent maternal grandparents. He learned all the skills necessary for farming and was especially good with animals, claiming he could break the wildest horses. He drew constantly from at least seven or eight years of age, often copying pictures of horses his grandfather saved, thus using printed source materials as compositional models, just as he would later in life.

Hawkins moved to Columbus, Ohio, at the age of 21. Thrust into city life with only a third-grade education, he took on many different jobs to support himself. He married and divorced twice and supported numerous children and grandchildren during his long, vigorous life. His most steady early employment was as a truck driver for building contractors. The changing skyline he saw while driving constantly intrigued him and contributed to the urban settings of his paintings.

In the 1930s and 1940s Hawkins occasionally sold a few paintings for small sums. An inveterate scavenger, he collected cast-off materials, which he used for many of his later works. His earliest surviving paintings date from the late 1970s to 1981. Landmark buildings and the American Wild West were his usual subjects. The latter may be accounted for by Hawkins’s claiming American Indian and white blood, a mix that he proudly said made him special.

Hawkins’s early paintings had unmixed colors, limited to black, white, and gray for the most part. Their scale was small, and their compositions were freely adapted from pictures in magazines and newspapers. Because he could not afford frames, he often painted one around the edges of his paintings, adding his name, birthday, and often his place of birth—(“William L. Hawkins born KY July 23, 1895”)—as an elaborate signature.

In 1981 Lee Garrett, a trained artist, discovered the works of William Hawkins and shortly thereafter a New York Gallery introduced his work to the public. With Garrett’s encouragement, Hawkins began experimenting. He used a range of bright colors, larger surfaces, and applied paint more freely, sometimes adding a paste of corn meal and enamels. Variations on the printed letters of his signature became larger, and bolder, to form integral parts of his compositions. Around 1986, Hawkins added collage and three-dimensional elements to his works. By this time, Hawkins’s average paintings ranged from four to six feet or more in height and width. His preferred support was Masonite, which he worked with a single brush. Hawkins wanted to give each of his clients something distinctive; he never copied his work even if he returned to a subject more than once. He once said, “There are a million artists out there and I try to be the greatest of them all.” Today his works can be found in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the High Museum, and the New Orleans Museum of Art.

N. F. KARLINS

New York, New York

Columbus Museum of Art, Popular Images, Personal Visions: The Art of William Hawkins, 1895–1990 (1990); Frank Maresca and Roger Ricco, William Hawkins: Paintings (1997); Riffe Gallery, William Hawkins: Drawings in Context (2000).

Heltzel, Henry (Stony Creek Artist)

(birth and death dates unknown)

Henry Heltzel, formerly known only as the Stony Creek artist, produced fraktur for members of the German Lutheran and Reformed Zion Church at Stony Creek in Shenandoah County, Va. H. E. Comstock identified the artist in 2005 while examining a copybook made for George Peter Dobson of Shenandoah County. This copybook, now in the collection of the Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, contains the signature “H. Heltzel” and the date 16 February 1826. The 40 works attributed to this artist date from 1805 to 1824 and include both German- and English-language examples. Most of the artist’s frakturs were made for children in Shenandoah County, Va., although at least six are from the area of Shepherdstown, W.Va. Scholars such as Klaus Wust have suggested that the artist may have been the schoolmaster at the parochial school associated with Zion Church on the Schwaben Creek, located near Stony Creek. Fraktur attributed to Heltzel include birth and baptismal certificates as well as bookplates.

Scholars have based attributions to Heltzel on several distinctive motifs: hand-drawn curtains at the top and sides of the certificate that often flank a central large heart containing the text; winged angels’ heads drawn above the heart; floral borders that frame the text; and devices such as four- or five-petaled blooms, either roses or pansies, and fleurs-de-lis that occupy the corners of floral borders. However, as other southern fraktur artists, such as the Virginia Record Book Artist, also drew curtains and fleur-de-lis, attributions cannot be made on these elements alone. The Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library hold examples of Heltzel’s fraktur.

LISA M. MINARDI

Winterthur Museum and Country Estate

H. E. Comstock, Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts (Winter 2005–Winter 2006); Russell D. Earnest and Corinne P. Earnest, Papers for Birth Dayes: Guide to the Fraktur Artists and Scriveners (1997); Cynthia Elyce Rubin, ed., Southern Folk Art (1985); Klaus Wust, Virginia Fraktur: Penmanship as Folk Art (1972).

Hesselius, John

(ca. 1726–1778)

Around 1711 Gustavus Hesselius, a Swedish artist, and his wife, Lydia, were among a large number of Swedes who settled in the Christiana-Wilmington area of Delaware. Others in the family went first to Pennsylvania. Gustavus moved to St. George’s County, Md., at an undetermined date and sold his land there in 1726. John Hesselius, his son, was probably born that year, presumably in Philadelphia, Pa., where his parents had moved and would live until their deaths.

John’s father, Gustavus, painted portraits in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and possibly Virginia, because one work from that colony is attributed to his hand. In Philadelphia he advertised that he was from Stockholm and that, in addition to painting portraits, he painted landscapes, coats of arms, signs, and showboards. He was also skilled in ship and house painting, gilding, and restoring pictures. John learned how to do all of these branches of painting, decorative and utilitarian, from his father. John’s earliest likenesses, however, show the strong influence of another artist, Robert Feke, who visited Philadelphia in the 1740s. Feke’s rich colors and more fashionable compositions impressed the younger, ambitious painter, who quickly adopted them in some of his earliest portraits.

Hesselius may have painted in Virginia as early as 1748. As many as 12 portraits have been identified as his work for the 1748–49 period in Virginia; many others were painted after this. His father’s death in 1755 seems to have provided a greater opportunity for the young Hesselius to make painting trips to Virginia and Maryland. By 1759 he had moved his residence to Maryland. On 30 January 1763 he married Mary Young Woodward, the widow of Henry Woodward of Anne Arundel County. The couple raised eight children, including a son named Gustavus. Either this year or the previous one, Hesselius traded painting lessons to Charles Willson Peale for a saddle.

Sometime around 1756, Hesselius’s portrait compositions and painting style changed dramatically and became based on the highly successful work of the London-trained painter John Wollaston. The latter worked in the Mid-Atlantic region from about 1755 to 1758. Hesselius softened his colors to more pastel shades and switched to more graceful, flowing poses for sitters in imitation of the rococo style that Wollaston practiced.

Hesselius continued to work in this fashion until the last years of his life, changing his approach to one of greater realism and eliminating the opulent and mannerist characteristics associated with the rococo. The artist’s late work was probably influenced by neoclassicism, first introduced in America by studio-trained painters like Henry Benbridge and Hesselius’s former pupil Charles Willson Peale.

At the time of his death on 9 April 1778, Hesselius left an impressive estate of household furnishings, cash, and land holdings. Many museums, including the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, hold Hesselius’s works.

CAROLYN J. WEEKLEY

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Richard K. Doud, “John Hesselius: His Life and Work” (M.A. thesis, University of Delaware, 1963); Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (April 1967).

Highwaymen

The story of the Highwaymen is an unlikely one. This group of young African American artists living near Fort Pierce, Fla., during the early years of the civil rights movement rose above existing societal expectations and produced a large body of oil paintings that document the mid-20th century landscape of the Sunshine State. For most of their careers, the artists worked anonymously, remaining unrecognized and uncelebrated until they were given the name “Highwaymen” in a magazine article in 1994, some 30 years after the beginning of their loose association.

Alfred Hair, who had begun painting on his own in 1955, enlisted and encouraged friends and family members to join him, so that they might escape their likely destinies working in Florida’s orange groves and packinghouses. They painted in their yards, often collectively through the night, and then took their still-wet creations to the streets to sell. These self-taught painters were entrepreneurs who became artists by default. Creating fine art was never their objective; acquiring wealth was their goal.

The artists worked feverishly for more than a decade. To them, time was money. The haste with which they painted each picture, often less than an hour, resulted in a distinct style that was misunderstood by many art fanciers. Characterized by early critics as “motel art,” the wind-swept palm trees, billowing cumulus clouds, moody seas, and intensely colored sunsets seemed to idealize Florida in archetypal tropical scenes meant to appeal to the masses. Nonetheless, the paintings became popular representations of how residents and tourists alike viewed the state.

Through their practice of fast painting, the Highwaymen created, or at least contributed to, a fresh approach to the tradition of American landscape portrayal. Their images are not generally detailed or treated in a grand manner; rather, they reveal temporal places in the process of becoming fully formed. The gesturally painted images, stripped of artifice, encourage viewers to lend their own inspirational meanings to these works of art.

Today the story of the Highwaymen is a significant part of Florida’s folk life and history. Even larger, perhaps, is the contribution that this tale makes to our national story. After all, the accomplishment of the Highwaymen is a saga about American dreams realized by a disenfranchised group of young people during a most oppressive time. Their visual legacy of Florida, depicted in as many as 200,000 paintings, has come to symbolize not only the beauty of the area but also the hopes and aspirations of its inhabitants. Works by the Highwaymen appear in the collection of the Museum of Florida History.

GARY MONROE

Daytona State College

Gary Monroe, Extraordinary Interpretations: Florida’s Self-Taught Artists (2003), Harold Newton: The Original Highwayman (2007), The Highwaymen: Florida’s African-American Artists (2001).

Hill, Kenny

(b. 1950)

In 1990 Kenny Hill of Chauvin, La., began to transform his property on the Bayou Petit Cailou into a complex art environment. Having moved to the undeveloped lot in 1988, Hill camped while building himself a small but unusual home. Little is known about the reclusive Hill, but he insisted to neighbors that his work was a personal endeavor not meant for an audience; he regularly declined requests from would-be visitors and photographers. He stated, simply, that the project was “a story of salvation.”

Indeed, Hill’s project, envisioned and executed in the final decade of the millennium, is devoted to the artist’s complex apocalyptic vision. Some one hundred concrete figures and architectural features, baroquely posed and brightly painted, populate a series of tableaux describing an eternal fight between good and evil. Hill’s vision is both personal and prophetic. Representing his own visage repeatedly throughout the site, he casts himself as the penitent seeking redemption.

The overall atmosphere Hill created is one of drama and action, intensified by Hill’s bold colors and the lush bayou landscape. Angels are omnipresent, guarding, flying, uplifting, some benevolent, others condemning. On one path, tarry black figures of the damned writhe in agony. Other pathways lead to nine circular platforms, each of which features nine spheres relating to a radiating orb, generally read as the nine planets that revolve around one shared sun. Much of Hill’s symbolism is arcane, but throughout the site it is possible to discern an intentional layering of the patriotic, the spiritual, and the cosmic.

The central feature of the site is a 45-foot-tall brick lighthouse in which Hill’s expertise in the trade of masonry is evident. The tower, ostensibly referencing the Tower of Babel, is covered with figures both heavenly and earthbound. American history is referenced through Christopher Columbus’s ship the Santa Maria, cowboys, Native Americans, World War II soldiers at Iwo Jima, and even a jazz funeral. Angels hoist mortals—Hill among them—toward the heavens as God surveys the scene. The tower itself is topped by a flying eagle, an emblem not just of the United States but—and perhaps more significantly here—a symbol for St. John the Evangelist, author of the book of Revelation (or Apocalypse of John) in the Bible’s New Testament.

In January 2000 Hill abandoned the site and fell away from the church that had once been central in his life. Perhaps disillusioned when the Apocalypse did not arrive, Hill never returned to his remarkable environment. By the time the artist left, parts of the site were already decomposing. The Kohler Foundation undertook the site’s preservation and built a bulkhead to stave off the encroaching bayou. In 2001 the Kohler Foundation gave the conserved site to Nicholls State University in Thibodaux, La., which agreed to see to the art environment’s ongoing care. The site features a studio building and art gallery and is open to the public. From the artist’s family, the Kohler Foundation has acquired in 2010 a recent sculptural self-portrait and donated it to the John Michael Kohler Arts Center.

LESLIE UMBERGER

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Deborah H. Cibelli, Raw Vision (Winter 2008); Leslie Umberger, Sublime Spaces and Visionary Worlds: Built Environments of Vernacular Artists (2007).

Holley, Lonnie

(b. 1950)

The works of Alabama-bred artist Lonnie Holley ably demonstrate how African American vernacular traditions adapt to sociological and technological change. Rooted in the cultural practices of yard shows and yard art, Holley has, since he began to make art in 1979, expanded his creative vision to embrace media as diverse as sandstone carving, found-object assemblage, oil and acrylic paintings, photography, computer-based art, and music. Holley has also worked in a range of scales, from miniature to monumental. When in the company of admirers, Holley further vitalizes his art with brilliant spoken-word performances that situate his work—so concerned with current events and societal wounds—within black American customs of preaching and storytelling.

The seventh of 27 children, Holley was born in Birmingham, Ala., which has remained his center of operations for six decades. Holley grew up in a series of foster homes and reform schools, lived his teenage years on the edge of the law, and ultimately worked as, among a series of jobs, a short-order cook at Disney World. In the late 1970s he drifted back to Birmingham, where, tormented by the deaths of two nieces, he made his first carvings, small grave monuments for the girls. He then moved onto ancestral property, then used as a communal dump, close to the Birmingham airport. There he continued making commemorative carvings from a sandstonelike slag cast off by Birmingham’s industrial foundries.

Holley’s carvings honoring the dead soon sought to understand death in the context of the deceased’s social and personal situations, interlacing biographies with critiques of racial and economic injustice, examinations of family responsibilities, the family unit, and the paradoxes of human nature. By the early 1990s, Holley’s site had grown to more than an acre, sprawling beyond his property lines to interact with its neighborhood, a stereotypically poor, crime-encumbered, and nearly all-black quarter of Greater Birmingham. Numerous works erected in half-seen or abandoned spaces connected the most local of stories—friends’, neighbors’, and family members’ lives—to grander cultural narratives. Scavenging not just debris but significant remnants of the stories of people he knew, the artist created, on a scale perhaps unparalleled in American art, a conceptual tapestry of seemingly infinite intricacy. His yard and surroundings dehisced thousands of artworks whose overarching theme was degradation—of peoples, of the earth, of history, of gender, of race, and of class—and the inexplicable will to endure. Perhaps nowhere else has the rupture of the civil rights movement been so lyrically inscribed on the physical world.

Holley’s site finally found itself, in the mid-1990s, fatally and tragically entangled with the very social forces it had documented: the local government targeted Holley’s neighborhood for demolition in preparation for a planned expansion of the municipal airport. After a long holdout and legal struggle, during which his site was continually vandalized, in 1997 Holley relocated what portions of his work he could to the rural community of Harpersville, Ala. His new locale never embraced his presence or his art, and while the artist set about making a yard show there in the vein of his earlier one, by the 2000s he was spending most of his time in a rented studio in Birmingham. In 2011 he moved to Atlanta, where he continues to create visual art in many mediums and has developed a following for his genre-bending music. Holley’s work is in the collections of many institutions, including the American Folk Art Museum, the Birmingham Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art, the Milwaukee Museum of Fine Arts, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the New Jersey State Museum.

PAUL ARNETT

Lafayette, California

Paul Arnett and William Arnett, eds., Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art of the South, vol. 1 (2000); Andrew Dietz, The Last Folk Hero: A True Story of Race and Art, Power and Profit (2006).

Hoppe, Louis

(b. 1812; d. unknown)

Louis Hoppe is little known in the field of Texas art. Biographical information is scant, and Hoppe’s paintings are scarce. Only four paintings—all watercolors currently in the collection of the Witte Museum in San Antonio, Tex.—are known. Images of these paintings, along with a handful of facts about Hoppe’s life and career, were first presented in Cecilia Steinfeldt’s landmark Art for History’s Sake: The Texas Collection of the Witte Museum. Steinhardt’s research revealed that Hoppe was a German immigrant who worked as a laborer on the east Texas farms of Johann Leyendecker and Julius Meyenberg.

Although Hoppe is often described as an “itinerant” laborer, additional information about Hoppe, including a very thoughtful letter he sent back to his hometown of Koblenz, Germany, after his arrival in the United States, presents the image of a man who was well educated and well spoken. Hoppe was born the son of a soldier in the Prussian army in 1812, and in 1851 he was married. Just two months later his wife passed away. Hoppe left Germany the following year, arriving in 1852 in New York, where he decided to become a painter.

Shortly after his arrival in the United States, Hoppe traveled to Texas, where in the early 1860s he painted all of his known works. One of the watercolors, Julius Meyenberg’s Farm, includes on its front a painted caption, which, in English, reveals that the farm is located on a bluff over William Creek in a settlement by La Grange. A more important function of this, and indeed all of Hoppe’s paintings, is the wealth of pictorial information on a place and time neither frequently depicted by artists nor readily captured by camera.

The main elements of the painting—the farmhouse, garden, animals, and family members—are executed in the simple, linear style and frontal perspective typical of the work of self-taught artists. While the house, the center of family and farm life, is the largest element in Hoppe’s painting, the elements of nature, most notably the garden, surrounding trees, and family horse predominate. The supremacy of nature is further underscored by the representation of Meyenberg’s family as dwarfed by his property and the many natural blessings of Texas.

Whereas Hoppe obscured the farmhouse in the Meyenberg painting, in his depiction of the Leyendecker farm the farmhouse is given a much more prominent role. In Art for History’s Sake, Steinfeldt describes in detail the architectural and historic importance of the house, and Hoppe himself was clearly aware of the importance of this building, as it is the house and cleared land around it that dominate the painting. Nature is lushly displayed on the perimeter, but on center stage are the industrious efforts of humans.

The two other paintings by Hoppe—still lifes of bunches of wildflowers—reflect Hoppe’s German heritage. These two watercolor and ink works, one entitled Zur Errinerung, or In Memory, belong to a Germanic tradition of commemorating life events with small works on paper. These works, which may have been made as personal commemorations or given as gifts, draw on the same precedents as frakturs. Like his landscapes, these still lifes return to a celebration of nature. Though not as dense with detail as the two farm paintings, Hoppe’s still lifes reflect his commitment to an earnest pictorial description of the world he inhabited. When combined with his farmhouse paintings, the work of Hoppe may be seen as perpetuating a myth of the West where on the frontier Mother Nature meets the taming efforts of human nature.

A. KATE SHEERIN

Witte Museum

Pauline A. Pinckney, Painting in Texas: The Nineteenth Century (1967); Cecilia Steinfeldt, Art for History’s Sake: The Texas Collection of the Witte Museum (1993).

Hudson, Julien

(ca. 1811–1844)

Most likely the son of London-born John Thomas Hudson, a ship chandler and ironmonger, and Suzanne Désirée Marcos, a free quadroon, Julien Hudson is thought to have been a free man of color. However, he is not listed as such, as was the custom, in the 1838 New Orleans City Directory. Like his racial identity, the date of his birth has been a matter of intense scrutiny for many years, but scholars have recently determined his birth date as 9 January 1811. Hudson’s father apparently did not live with the family after about 1820, but his mother maintained a comfortable standard of living, owing to presumed support from her husband in addition to her and her mother’s real estate investments. Julien probably studied grammar, mathematics, and other subjects with a private tutor in the French Quarter at their home on Bienville Street near Bourbon. In 1826–27 he studied art with itinerant Antonio Meucci, a drawing instructor, restorer, and painter of miniatures and opera scenery. Upon his grandmother’s death, Hudson inherited part of Françoise Leclerc’s $7,000 estate in 1829, which allowed him to pursue further study in Paris. When he returned in 1831, Hudson advertised his services as a portrait painter, noting both his training with Meucci and a “complete course of study . . . as a miniature painter” in Paris.

Hudson remained in New Orleans until at least 1832. He may have traveled to other cities in the United States before returning to Paris in 1837 to study with Alexandre-Denis Abel de Pujol, a student of Jacques-Louis David. The second trip was cut short, perhaps because of the death of his sisters and legal difficulties incurred by his mother, and Hudson returned to New Orleans. He maintained a residence at 120 Bienville Street, though he appears in the City Directory as an artist only in the years 1837–38. All of the surviving paintings with secure attributions date to the late period. George David Coulon studied, at least briefly, with Hudson in 1840. Hudson died in 1844.

Only two works can be securely attributed to Hudson; one portrait has been identified since the 1930s as a self-portrait, and the other is a verified likeness of Jean Michel Fortier III. Two additional paintings have recently been discovered with plausible attributions to Hudson’s hand. Hudson’s portraits possess a stasis and rigidity that betray an intractable connection to folk painting. Strikingly absent is any sign of Parisian academic training. The Self Portrait in particular, given its tiny scale and cut-off oval format, suggests Hudson’s training as an artisan maker of miniatures. Minute wisps of paint delineate each hair with the rigorous precision of one accustomed to working on a very small scale. Hudson’s crisp modeling and the unflinching gaze of his sitters imbue his polished, gemlike compositions with an undeniable power and make compelling statements about self-perception, identity, and social status.

RICHARD A. LEWIS

Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans

Patricia Brady, International Review of African American Art (1995); New Orleans Bee (6 June 1831); David C. Driskell, Two Centuries of Black American Art (1976); Robert Glenck, Handbook and Guide to the Louisiana State Museum (1934); John Burton Harter and Mary Louise Tucker, The Louisiana Portrait Gallery: The Louisiana State Museum, vol. 1, To 1870 (1979); Historic New Orleans Collection, Encyclopedia of New Orleans Artists (1987); Regina A. Perry, Selections of 19th Century Afro-American Artists (1976); James Amos Porter, Ten Afro-American Artists of the Nineteenth Century (1967); William Keyse Rudolph, Patricia Brady, and Erin Greenwauld, In Search of Julien Hudson: Free Artist of Color in Pre-Civil War New Orleans (2011); Anne C. Van Denvanter and Alfred V. Frankenstein, American Self-Portraits, 1670–1973 (1974).

Hunter, Clementine

(1886 or 1887–1988)

The granddaughter of slaves, Clementine Hunter was born Clemence Reuben in late 1886 or early 1887. When she was a teenager, she moved with her family to Melrose Plantation, near Natchitoches, La. Working as a field hand, as a domestic servant, and finally as an artist, Hunter remained at Melrose for most of her life. She married twice and gave birth to seven children. As a domestic worker, Hunter came to know the writers and artists that Cammie Henry, the mistress of the plantation, welcomed to Melrose. Hunter’s observations of the artwork of Henry’s guests undoubtedly inspired Hunter to try her hand at painting. Regular guests, writer James Register and François Mignon, who had been born Frank Mineah in New York but reinvented himself as a French art critic, became early patrons. These supporters helped with finances, collected art supplies, and encouraged Hunter to paint the farming scenes, river baptisms, wakes, and funerals that they knew would appeal to collectors. Mignon also suggested that Hunter paint the 1955 panoramic murals of farming, worship, and social life that decorate the African House, described by the Historical Building Survey as the only Kongo-style structure built by enslaved blacks in the United States. Scholars have also noticed possible influences from France and creolized Caribbean architecture.

Hunter’s primary inspiration was her appreciation of African American life. Clementine Hunter summed up her four-decade long career: “I paint the history of my people. My paintings tell how we worked, played, and prayed.” With bold stokes of saturated color, Hunter remembers the work performed by African Americans at Melrose: washing clothes in huge iron pots, shaking pecan trees and gathering the nuts, slaughtering hogs, and, of course, working in the cotton fields. Quilts that depict the main house and other plantation buildings demonstrate aesthetic preferences identified as African: large sections of solid, contrasting colors, irregular but rhythmic sashing, and appliqué. Equally vibrant are paintings of favorite pastimes such as fishing, playing cards, and dancing.

The remaining works, like much of southern folk art, address religious life. Hunter, however, does not share the evangelical fervor of the many Protestant preacher-artists. With French, Irish, American Indian, and African American ancestry, Hunter belonged to a distinctive community of Creoles of color who have lived in Natchitoches Parish for more than 250 years. Hunter, who spoke only French until she married Emanuel Hunter when she was in her thirties, was proud of her Creole heritage, defined not only by ethnicity but also by Catholic faith. Hunter had received her brief education from French-speaking nuns, and until her death she was a member of St. Augustine’s Catholic Church, the first Catholic parish in the United States founded by and for persons of color. Hunter’s paintings of religious life reflect her Catholic background and familiarity with Catholic sacred art.

Unlike the creations of southern Protestants, Hunter’s works are not Bible based. While Hunter certainly knew Bible stories from her attendance at the Baptist Church, where she enjoyed singing, her only biblical scenes are nativities and crucifixions. All adopt aesthetic preferences often associated with Catholic art—centrality of important figures, symmetry as shown in pairs of candles and urns, and hazy pink and blue backgrounds that emphasize the otherworldliness of the sacred figures. Holy cards, inexpensive devotional prints that have long disseminated Catholic visual culture, are likely sources. The more than 100 crucifixions Hunter painted of a black Jesus are clearly based on Catholic prints. Her masterful Cotton Crucifixion (1970) is a particularly powerful adaptation of holy cards that depict a reciprocal relationship between a localized suffering black Jesus and a community of color.

Hunter’s Catholic faith, however, did not deny her the expressive worship of Protestant neighbors. Her paintings of river baptisms and revivals attest to her familiarity with those most Protestant of services. Her paintings of wakes and funerals record shared community values. Hunter’s many wedding paintings, in which solemn brides tower over both grooms and diminutive peripheral ministers, show Hunter’s feelings toward marriage.

Hunter’s memory paintings, estimated in the thousands, are a nuanced history of a place on the verge of change. Before her death in 1988, at the age of 100 or 101, Hunter had witnessed the mechanization of farming and the migration of African Americans to urban centers. Most importantly, African Americans had become outspoken about racial injustice. In 1955 Hunter had not been allowed to attend the opening of her exhibition at a “white” college but had had to sneak in on Sunday with a professor who had keys to the locked gallery. By 1988 Clementine Hunter was a celebrated artist featured in seminal books on folk art, profiled in magazines, and collected by important museums. Hunter’s works can be seen at the American Folk Art Museum, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Louisiana State Museum, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the High Museum of Art, the Morris Museum, and the Dallas Museum of Art. The Association for the Preservation of Historic Natchitoches maintains the Melrose Historic Plantation Complex, which is a National Historic Landmark.

CHERYL RIVERS

Brooklyn, New York

Robert Bishop, Folk Painters of America (1979); Carol Crown and Charles Russell, eds., Sacred and Profane: Voice and Vision in Southern Self-Taught Art (2007); David C. Driskell, Two Centuries of Black American Art (1976); Shelby R. Gilley, Painting by Heart: The Life and Art of Clementine Hunter, Louisiana Folk Artist (2000); Herbert W. Hemphill Jr. and Julia Weissman, Twentieth-Century American Folk Art and Artists (1974); François Mignon, Plantation Memo: Plantation Life in Louisiana, 1750–1970, and Other Matter (1972); Art Shiver and Tom Whitehead, Clementine Hunter: The African House Murals (2005); James L. Wilson, Clementine Hunter, American Folk Artist (1990).

Hussey, Billy Ray

(b. 1955)

Billy Ray Hussey was born in Moore County, in central North Carolina, in 1955. The great-grandson of traditional potter J. H. Owens and grandnephew of potter Melvin L. Owens, Hussey grew up steeped in the rich heritage of 19th-century utilitarian ware. By the age of 10 he was working in M. L. Owens’s shop, learning every aspect of making ware from preparing the clay to turning vessels, glazing, and firing. By age 20, he was working on his own for M. L. and for his cousin, Vernon Owens, at Jugtown Pottery. Hussey turned pottery and hand-sculpted figural pieces.

In 1979 a customer ordered several small, unsigned pottery lions based on images from William Wiltshire’s book Folk Pottery of the Shenandoah Valley, published in 1975. Some of these lions had made their way from southwestern Virginia into the marketplace, causing a stir because of their resemblance to lions made by the famous Bell potters of the Shenandoah. Once collectors discovered that Hussey was the lions’ maker, Hussey received considerable attention. He began signing his work “BH” and “Owens Pottery.” After acquiring his own kiln, Hussey dropped the “Owens Pottery” designation.

By the 1980s, Hussey was working as a full-time potter. Although it was 1988 before he completed his own operational shop and kiln, by 1986 he had begun to have kiln openings once or twice a year. Hussey began numbering the sale on each piece. In recent years he has been signing his work with a recumbent B, with the kiln sale number inscribed in the curves of the letter. Thus, pieces can be roughly dated by number and signature. In 2007, when he completed kiln no. 54, Hussey estimated that he had produced nearly 3,000 pieces.

Around 1990, Hussey began working with entrepreneurs who had established a company, the Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society, to sell traditional southern pottery and to promote and sell Hussey’s pottery. By 1994, Hussey and his wife, Susan, were owners of the company. Twice a year they conduct sales of consigned traditional pottery, producing a catalog with information about each piece. Hussey markets his own work through events sponsored by the Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society.